Abstract

Rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases are ubiquitous enzymes that catalyze the transfer of sulfane sulfur from a donor molecule to a thiophilic acceptor via an active site cysteine that is modified to a persulfide during the reaction. Here, we present the first crystal structure of a triple-domain rhodanese-like protein, namely YnjE from Escherichia coli, in two states where its active site cysteine is either unmodified or present as a persulfide. Compared to well-characterized tandem domain rhodaneses, which are composed of one inactive and one active domain, YnjE contains an extra N-terminal inactive rhodanese-like domain. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that YnjE triple-domain homologs can be found in a variety of other γ-proteobacteria, in addition, some single-, tandem-, four and even six-domain variants exist. All YnjE rhodaneses are characterized by a highly conserved active site loop (CGTGWR) and evolved independently from other rhodaneses, thus forming their own subfamily. On the basis of structural comparisons with other rhodaneses and kinetic studies, YnjE, which is more similar to thiosulfate:cyanide sulfurtransferases than to 3-mercaptopyruvate:cyanide sulfurtransferases, has a different substrate specificity that depends not only on the composition of the active site loop with the catalytic cysteine at the first position but also on the surrounding residues. In vitro YnjE can be efficiently persulfurated by the cysteine desulfurase IscS. The catalytic site is located within an elongated cleft, formed by the central and C-terminal domain and is lined by bulky hydrophobic residues with the catalytic active cysteine largely shielded from the solvent.

Keywords: persulfide, phylogenetic analysis, rhodanese, sulfurtransferase, x-ray crystallography

Introduction

Sulfurtransferases/rhodaneses catalyze the transfer of a sulfane sulfur from a donor molecule to a thiophilic acceptor. These enzymes are widely distributed in plants, animals, and bacteria and have been implicated in a wide range of biological processes like cyanide detoxification, sulfur and selenium metabolism, and synthesis or repair of iron-sulfur proteins.1 Rhodaneses (thiosulfate:cyanide sulfurtransferases or TSTs, EC 2.8.1.1) catalyze the transfer of a sulfane sulfur atom from thiosulfate to cyanide in vitro. 3-Mercaptopyruvate:cyanide sulfurtransferases (MSTs, EC 2.8.1.2) catalyze a similar reaction, using 3-mercaptopyruvate as the sulfur donor. Both types of enzymes catalyze the sulfurtransferase reaction via the formation of a persulfide sulfur covalently bound to the sulfur of a catalytic Cys and display significant levels of sequence similarity, indicative of their common evolutionary origin.1,2 The active site Cys is the first residue in a six amino acid active site loop, which defines the active site pocket.

Rhodanese-like proteins are however a heterogenous superfamily; the variability occurs at different levels including sequence similarity, active site loop length, conformation, and amino acid composition of the active site loop, the presence or absence of the critical catalytic Cys residue, and, in the case of multidomain rhodaneses, their domain arrangement.1 Rhodanese-like proteins are either composed of a single catalytic rhodanese domain, fusions of two rhodanese domains (tandem domain), in which the C-terminal domain contains the catalytic cysteine following an N-terminal inactive domain or rhodaneses composed of up to six domains with various combinations of active and inactive domains. Rhodaneses are also found combined with other protein domains of different functions1 such as ThiI and ThiF/MoeB-related proteins,3,4 which are involved in the metabolism of the sulfur-containing compounds thiamin and the molybdenum cofactor. A further group is represented by the so-called elongated active site loop proteins, which are restricted to eukaryotes and include the Cdc25 phosphatases.5,6 Biochemical data support the hypothesis that rhodanese domains displaying a seven-amino acid loop are able to bind substrates containing a phosphorous or the chemically similar arsenic atom, whereas rhodanese-like domains displaying a six-amino acid loop with Cys at the first position interact with substrates containing a reactive sulfur, or in some cases a selenium atom.2

In the Escherichia coli genome eight genes have been identified encoding proteins consisting of a rhodanese-like domain bearing a conserved cysteine residue as potential active site for persulfide formation.7,8 Three of the corresponding gene products, GlpE,7 PspE,9 and YgaP feature a single rhodanese domain, SseA (MST)10 is composed of two rhodanese domains, while YnjE contains three rhodanese domains. In each case, the C-terminal domain contains the catalytic cysteine residue. The three remaining proteins, ThiI, YbbB and YceA, contain a single rhodanese module in the context of a larger protein. With the exception of ThiI and YbbB, which are required for thiamine/thiouridine and selenothiouridine biosynthesis, respectively, little is known about the in vivo role of the other rhodaneses.8,11

We present here the crystal structure of E. coli YnjE, the first structure of a triple-domain rhodanese-like protein, in its sulfur-free as well as in its persulfurated state. On the basis of structural comparisons with other rhodaneses and kinetic studies, YnjE is more similar to TSTs than to MSTs, but nevertheless has a different substrate specificity that depends not only on the composition of the active site loop but also on the surrounding residues.

Results and Discussion

Structure of YnjE

Structures of YnjE in its sulfur-free and persulfide-intermediate state have been solved. As attempts to solve the structure by molecular replacement were unsuccessful, the phase problem was solved by single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) with a data set collected at the Se absorption edge at 0.9792 Å. Two YnjE monomers are present in the asymmetric unit (referred to as A and B), and 20 of the expected 20 selenium positions were located from the anomalous difference data using SHARP. The final protein model of the persulfide structure, refined at 2.4 Å resolution to a crystallographic R-factor of 16.1% and a free R-factor of 21.1%, contains 828 residues and 560 water molecules (Table I). The N-terminal His6-tag as well as the first two amino acids are exposed to the solvent and are not visible in the electron density maps.

Table I.

Data Collection, Phasing, and Refinement Statistics

| Data set | Persulfide | SeMet-Peak | Sulfur-free |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and phasing | |||

| Resolution (Å)a | 41.0–2.4 (2.53–2.4) | 69.8–2.8 (2.95–2.8) | 50.1–2.4 (2.53–2.4) |

| Space group | P6322 | P6322 | P6322 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a = b, c (Å) | 160.9, 174.0 | 161.4, 173.1 | 160.9, 174.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.8 | 0.9792 | 0.9184 |

| Unique reflections | 52,432 | 33,339 | 51,064 |

| I/σ(I)ab | 25.7 (6.4) | 16.8 (4.5) | 20.9 (5.3) |

| Completeness (%)a | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancya | 21.8 (21.5) | 13.9 (14.4) | 14.6 (14.6) |

| Rsymac | 0.112 (0.551) | 0.171 (0.503) | 0.100 (0.536) |

| Rpimad | 0.035 (0.173) | 0.066 (0.192) | 0.027 (0.145) |

| Number of sites | 20 | ||

| Phasing powere | 0.675 | ||

| Mean figure of merit (Acentric/centric) | 0.29/0.11 | ||

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution limits | 41.0-2.4 | 46.4-2.4 | |

| No. of reflections | 49,744 | 48,445 | |

| No. of protein/ligand/solvent atoms | 6,607/58/560 | 6,569/45/431 | |

| Atoms | |||

| Rcryst (Rfree)af | 0.161 (0.211) | 0.167 (0.214) | |

| rms deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.017 | 0.019 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.601 | 1.695 | |

| Estimated coordinate error (Å)g | 0.196 | 0.199 | |

| Mean B-factor (Å2) | 35.3 | 29.4 | |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)h | 97.1/99.8/0.2 | 96.1/99.4/0.6 | |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the respective highest resolution data shell in each data set.

I/σI indicates the average of the intensity divided by its average standard deviation.

Rsym = ∑hkl∑i|Ii-〈I〉|/∑hkl∑i〈I〉 where Ii is the ith measurement and 〈I〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I.

Rpim is the precision indicating (multiplicity-weighted) Rsym.

Phasing power is the mean standard value of the heavy atom structure factor amplitude divided by the lack of closure for anomalous (ano) and isomorphous (iso) data.

Rcryst = ∑||Fo| − |Fc||/∑|Fo| where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes. Rfree same as Rcryst for 5% of the data randomly omitted from the refinement.

Estimated coordinate error based on Rfree.

Ramachandran statistics indicate the fraction of residues in the favored (98%), allowed (≥99.8%), and disallowed regions of the Ramachandran diagram, as defined by MolProbity.12

In the structure of the protein isolated from E. coli, the active site cysteine is oxidized, either to a sulfenic acid or a sulfinic acid (data not shown), and does not contain the catalytically active persulfide. Oxidation of active site cysteines, which might happen during purification, crystallization or data collection, is a frequently observed problem. However, as mass spectrometry of the freshly purified protein showed that the protein was partially purified with a persulfide bound to the active site, which was additionally confirmed by activity assays (data not shown), we rather believe that the oxidation occurred during crystallization and/or data collection. Anaerobic treatment of oxidized YnjE with DTT to remove oxidative modifications and subsequent incubation with L-Cys and the sulfurtransferase IscS resulted in the persulfurated active site Cys (see below). This observation demonstrates that at least in vitro the cysteine desulfurase IscS is capable of transferring the sulfur to YnjE. The same behavior has been reported for Azotobacter vinelandii rhodanese RhdA (Av_RhdA).13

The two YnjE molecules found in the crystallographic asymmetric unit can be superimposed with a root means square (rms) deviation of 0.55 Å calculated over 411 aligned residues. A search for structural homologs of YnjE with the program DALI,14 identified a large number of rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases. The tandem-domain rhodaneses from Thermus thermophilus (PDB entry 1uar), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (PDB entry 3hwi), Azotobacter vinelandii (Av_RhdA, PDB entry 1e0c) and Bos taurus (Rhodbov, PDB entry 1boi) with Z-scores of ∼30 and rms deviations of about 2.2 Å for about 265 aligned residues were the highest matches. When the search was performed with only the C-terminal catalytic domain the structure of Av_RhdA showed the highest Z-score (16.7) resulting in an rms deviation of 1.6 Å for 116 aligned residues. To determine the oligomeric state of purified YnjE, the protein was subjected to analytical ultracentrifugation sedimentation velocity (SV) analysis. The data were best described by a sedimentation coefficient distribution containing as the major component one hydrodynamically distinct species with an apparent sedimentation value of 3.5 S. The estimated apparent molar mass of 49 kDa is in good agreement with the theoretical molar mass calculated from the amino acid composition for a YnjE monomer plus the added N-terminal His-tag (47.7 kDa).

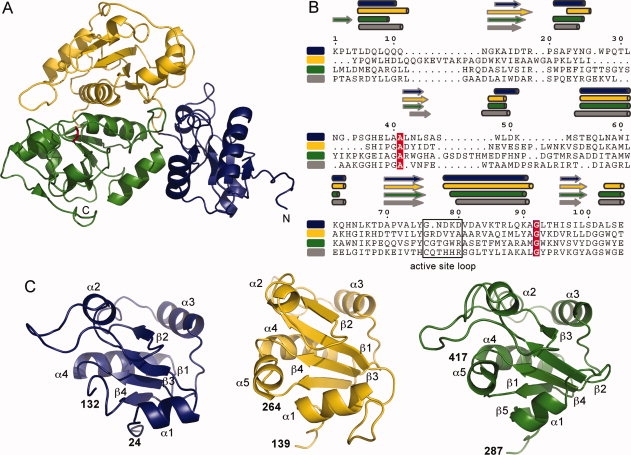

Monomeric YnjE is composed of an N-terminal, a central and a C-terminal domain, each exhibiting the rhodanese fold (Fig. 1). The N-terminal domain (residues 26–139) and central domain (residues 146–267) each contain a four-stranded parallel β-sheet surrounded by four and five α-helices, respectively, whereas in the C-terminal domain (residues 294–422) the central five-stranded parallel β-sheet is sandwiched by five α-helices. The C-terminal domain interacts with both the N-terminal and central domain, however, the interface with the central domain is more extensive with a buried interface of ∼2500 Å2. The three domains are connected via two extended polypeptide segments located on that face of the protein, which is opposite the active site. The central and C-terminal domains are assembled around a molecular pseudo 2-fold axis crossing the domain interface region. This interdomain interaction is mediated primarily by the longest α-helix (α4 in both domains) and the loop connecting α2 and α3. Superpositions of the central domain and N-terminal domain on the C-terminal catalytic domain result in rms deviations of 1.9 Å (102 aligned residues, 19.6% sequence identity) and 2.3 Å (98 aligned residues, 16.3% sequence identity), respectively, indicating a closer evolutionary relationship between the central and C-terminal domains.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the E. coli YnjE. A: Ribbon representation of YnjE. The N-terminal domain is shown in blue, the central domain in yellow and the C-terminal catalytic domain in green. The active site Cys385 in its persulfurated form is shown in stick representation in red. B: Structure based sequence alignment of the single domains [(green, C-terminal domain (aa 292–415); yellow, central domain (aa 147–260); blue, N-terminal domain (aa 28–132)] and the catalytic domain of Av_RhdA (gray). The secondary structure elements of each domain assigned using DSSP15 are labeled above the sequences. The alignment was performed using DaliLite16 and the figure was prepared with ESPript.17 Strictly conserved amino acids are highlighted with white letters in red. C: Architecture of the single domains with secondary structure elements labeled and color coded as in (A).

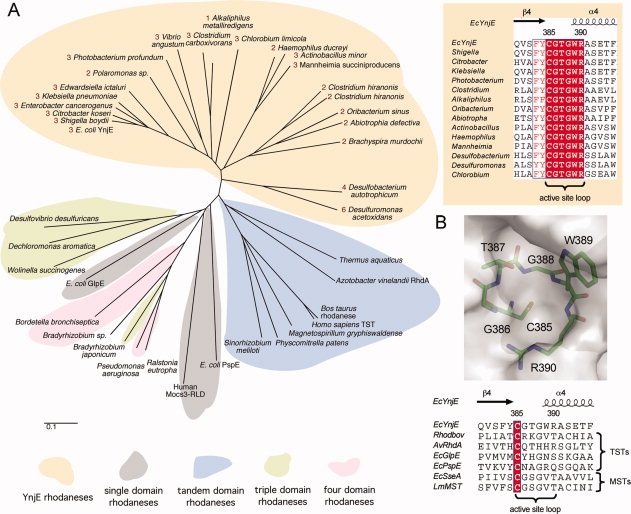

YnjE triple-domain homologues can be found in other bacteria, most of which are γ-proteobacteria, however, some single-, tandem-, four- and even six-domain variants of YnjE also exist in other bacteria. The YnjE homologous-rhodanese group is characterized by a highly conserved six amino acid active site loop (consensus sequence: CG[T/S]GWR) with the catalytic cysteine at the first position. Even though the tree derived by the neighbor-joining method is not very reliable in its deep branching, it becomes clear that the YnjE rhodaneses group together and separate from other rhodanese-types, of which some key representatives are shown (Fig. 2). As most YnjEs are triple-domain rhodaneses, they could have evolved independently either by fusion of a single-domain rhodanese with a tandem rhodanese, or by duplication of a tandem-domain rhodanese, followed by the loss of one domain. YnjEs with different domain numbers subsequently evolved, either by loss or fusion of domains from these YnjEs, giving rise to the diversity in the number of domains.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of rhodanese sequences. A: Protein phylogenetic analysis of rhodanese-like proteins with a major focus on YnjE-homologues. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method without correction for multiple substitutions and gap position exclusion. The scale bar indicates 0.1 substitutions per site. The numbering of YnjE-sequences indicates the number of rhodanese domains. Mocs3-RLD: C-terminal rhodanese-like domain of the human MOCS3 protein. Upper right: An alignment of the active site loops of selected members of the YnjE subfamily is shown. The alignment was performed using ClustalW18 and the figure was prepared as described in Figure 1. Strictly conserved amino acids are highlighted with white letters. B: Upper panel: The catalytic loop of YnjE is shown in stick representation superimposed on the molecular surface surrounding the active site. Lower panel: Alignment of the catalytic loops from structurally characterized TSTs and MSTs. The alignment and figure were prepared as described in (A). Strictly conserved amino acids are highlighted with white letters in red.

In general, rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases are frequently found as tandem repeats with the active site being always present in the C-terminal domain, or in combination with other protein domains. YnjE represents the first structurally characterized triple-domain member of the rhodanese superfamily. Inactive rhodanese-like domains lack the active site Cys, which is often replaced by acidic (Asp) or nonpolar residues. YnjE harbors a Gly at the first position of the “active site” loop in both of these domains [Fig. 1(B)]. Inactive rhodanese domains are also found in about one-third of the known dual-specific phosphatases (DSP), several ubiquitin peptidases (UBP) and the murine deubiquitinating enzyme UbpY.5,6 The role of the inactive rhodanese domains, either those found in TST and MST enzymes, or those associated with DSP or UBP, remains to be elucidated. It is speculated that they might be involved in recognition and binding of larger, hydrophobic substrates,19 or play a regulatory role (DSP and UBP). They also might be responsible for the stability of the protein, or be involved in mediating protein-protein-interactions with donor or acceptor proteins.

The active site of YnjE

Crystal structures of tandem-domain rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases revealed that the active site, with the catalytic cysteine, is situated in a cleft formed at the interface of both domains, although it is mainly constructed from residues located in the C-terminal domain.10,19–21 In YnjE the active site is located at the interface between the central and C-terminal domains [Fig. 1(A)]. The active site loop of YnjE with the catalytic Cys as the first residue consists of six residues (385CGTGWR390) as in other rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases1 although the terminal WR-dipeptide already belongs to the ensuing α-helix [Fig. 2(B)]. On the basis of the amino acid composition of the active site loop, YnjE is clearly more similar to MSTs (consensus sequence: CG[S/T]GVT) than to TSTs (consensus sequence: CRxGx[R/T]).2 However, in MSTs a serine-like triad, comprised of an Asp, His and a Ser residue, in close spatial proximity of the catalytic Cys represents a conserved feature that distinguishes MSTs from TSTs.20 YnjE lacks this conserved triad, which argues against the inclusion of YnjE in the MST subfamily.

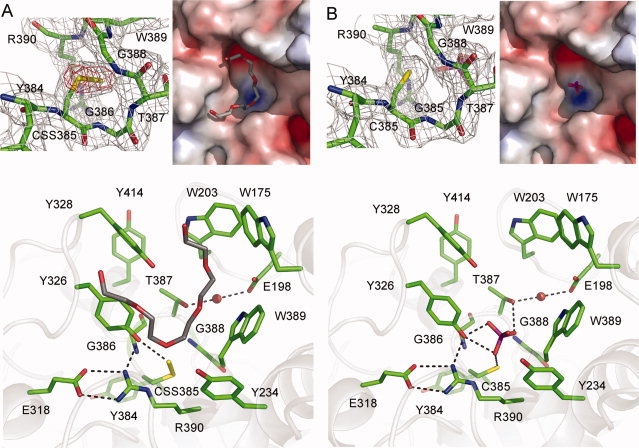

The active site loop of YnjE adopts a semicircular, cradle-like, conformation, which allows precise positioning of the Cys385 Sγ atom at the bottom and in the center of the active site pocket [Fig. 2(B)]. The bottom of the active site is formed mainly by the loop between β4 and α4 of the C-terminal domain. Placed at the center of the loop is the side chain of the catalytic Cys385, which is in the sulfur-substituted persulfide containing state, thus representing a reaction intermediate. As a 2.4 Å resolution structure may not allow for the unambiguous identification of the chemical nature of the Cys385 Sγ substituent, anomalous data from sulfur has therefore been measured at a wavelength of 1.8 Å to distinguish between a persulfurated sulfur or a sulfenic acid. Anomalous difference Fourier maps show the presence of a peak with an approximate height of 5.5 rms deviations demonstrating that the catalytic Cys is present in the persulfide state [Fig. 3(A)].

Figure 3.

The active site of YnjE. A: Structure of YnjE with the catalytic Cys in its persulfurated state. Upper left panel: SIGMAA weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density map contoured at one times the standard deviation around the active site cysteine in gray. Shown in red is the anomalous difference Fourier map contoured at four times the standard deviation calculated from data collected at a wavelength of 1.8 Å. Upper right panel: Electropositive (blue) and electronegative (red) surface potentials were calculated at an ionic strength of 150 mM and are contoured at ±10 kT/e. The bound PEG molecule is shown in stick representation. Lower panel: Active site architecture in the persulfide state. The bound PEG molecule is shown in stick representation. Dashed lines indicate H-bonds. B: Structure of YnjE with the catalytic Cys in its desulfurated state. Upper left panel: SIGMAA weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density map contoured at one times the standard deviation around the active site cysteine in gray. Upper right panel: Electrostatic surface representation with the bound phosphate molecule in stick representation. Lower panel: Active site architecture when the cysteine is not modified. The bound phosphate is shown in stick representation. Dashed lines indicate H-bonds.

The active site loop conformation in YnjE is such that six sequential main-chain NH groups (residues 386 to 391) point toward the site occupied by the Sγ and Sδ atoms, thus providing a network of radial hydrogen bonds (the S to N distances vary between 3.2 and 3.6 Å). This feature might be important for the stabilization of the negatively charged persulfurated catalytic Cys and reflects a precise tailoring (and likely substrate selectivity) of the catalytic pocket. At the same time these main-chain NH groups lower the pK of the active site cysteine in the absence of the persulfide modification, thus rendering it a stronger nucleophile. The peculiar active site loop structure creates a positive electrostatic field and the sterical properties of an anion-binding site. In addition, the Nɛ and Nη2 atoms of Arg390 are lining the edge of the active site pocket, at 3.4 Å and 3.7 Å distance from the Sγ atom, respectively, as a sort of arc completing the circular shape of the shallow pocket. In hydrogen bonding distance to the persulfide is the polar side chain of Tyr326 (3.2 Å). The “ring of persulfide-stabilizing NH groups” is similar to that observed in other rhodaneses19–21 but is different in the MST SseA from E. coli where the active site loop does not adopt a semicircular conformation.10 In SseA the active site loop is almost contained in the plane defined by the β-strand 4 and the axis of α-helix 4.

Bulky hydrophobic residues line the YnjE active site as well as the channel leading from the surface to the active site [Fig. 3(A)]. Additional residual difference density in the active site channel could be modeled in chain B as a polyethylene glycol (PEG) molecule (mean B-value 71 Å2) [Fig. 3(A)]. However, we cannot exclude that this residual difference density is derived from an unknown co-purified compound. The PEG molecule is bound at the interface between the central and C-terminal domain and restricts access to the active site cysteine. As in vitro YnjE can be efficiently persulfurated by the cysteine desulfurase IscS, in which the catalytic cysteine is located in a 10 amino acid surface loop, the bound PEG molecule could be located in the putative binding site of the IscS catalytic loop. Similar but less defined residual difference density is present in chain A. The catalytic site is located within an elongated cleft, which is created by two loop regions (173–177, 199–207) from the central domain and a third loop (320–348) located in the C-terminal domain [Fig. 3(A)]. The active site is largely shielded from the solvent by the aromatic residues Tyr328, Trp203, and Trp175 that are located in the aforementioned loop regions. We propose that in the presence of a donor or acceptor protein an opening of the active site channel occurs. In addition to these bulky hydrophobic residues, all active site residues that might be important for catalysis are highly conserved in the YnjE rhodanese-like proteins.

Treatment of native YnjE harboring a sulfinic acid at the active site with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and subsequent crystallization, both under anaerobic conditions, resulted in the cleavage of the persulfide bond yielding an unmodified Cys385 [Fig. 3(B)]. This structure was solved by difference Fourier synthesis at 2.4 Å resolution (Table I) and has been refined to an Rcryst of 16.7% (Rfree = 21.4%). Residual difference density in close proximity to the catalytic cysteine could be modeled as a phosphate ion [Fig. 3(B)], probably derived from the crystallization solution, either from the sodium citrate buffer or from TCEP which both contain phosphate impurities. This indicates that the phosphate is bound with high affinity. The phosphate ion is within hydrogen bonding distance of Cys385 Sγ (3.1 Å), Thr387 Oγ1 (2.9 Å), and Tyr326 OH (2.9 and 2.3 Å). The phosphate would prevent access to the catalytic center and is neither bound in the oxidized enzyme nor in the persulfurated form because of steric hindrance. There are no further structural changes associated with the removal of the active site persulfide linkage. The active site loops (residues 385–390) of sulfur-free and persulfurated YnjE superimpose with an rms deviation of 0.16 Å for 49 aligned atoms and there are no changes in side chain conformation. The residual difference density found in the persulfurated protein that has been modeled as a PEG molecule is only partly present in the sulfur-free state because of steric hindrance (distances <2 Å) with the phosphate.

For Av_RhdA it has been reported that cyanide, sulfite as well as phosphate and hypophosphite anions are able to remove the Cys persulfide sulfur.22 Crystallographic studies showed that hypophosphite, but not phosphate, is stably bound to the catalytic pocket of the desulfurated RhdA. In addition, no sulfate was bound at the active site, in spite of the 1.8M MgSO4 present in the crystallization solution. This indicates that in contrast to YnjE the active site architecture in RhdA does not allow an anion of the size of sulfate/phosphate to bind. As GlpE, a single domain rhodanese does not show inhibitory or structural effects in the presence of phosphate or hypophosphite,7 it has been speculated this may be linked to the presence of Arg235 as the last residue in the RhdA active site loop (Ser70 in GlpE, Arg390 in YnjE) [Fig. 2(B)]. Arg is also found in this position in Cdc25 phosphatases and likely provides stabilization for an active site anion.6 The reactivity of YnjE toward phosphate containing compounds remains to be investigated.

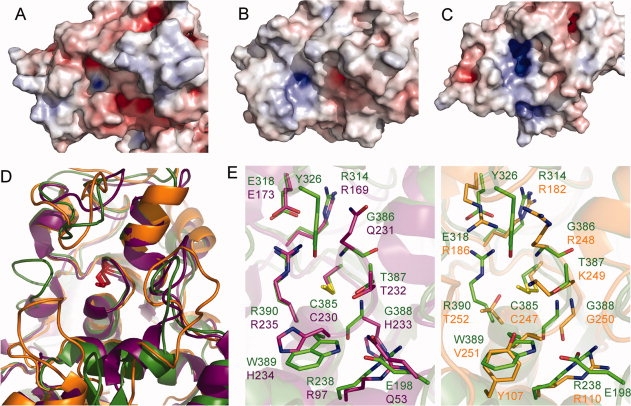

Comparison of YnjE with rhodaneses from the TST family

In general, the active sites of rhodaneses are positively charged to attract and then bind negatively charged ligands.20 However, the YnjE active site is less positively charged than those of Av_RhdA and Rhodbov [Fig. 4(A–C)] indicating that YnjE has a different substrate specificity. An analysis of the sulfurtransferase activity of YnjE Δ1-21 with 3-mercaptopyruvate, thiosulfate or cysteine as sulfur donors resulted only in a low activity towards thiosulfate (Table II), showing that YnjE likely uses a different sulfur substrate. The observed positive charge of the active sites of YnjE, Av_RhdA as well as Rhobov is reflected by the different amino acid compositions of the active site loops (YnjE: CGTGWR, Av_RhdA: CQTHHR, Rhobov: CRKGVT) as well as the surrounding residues. The active site loop of known TSTs always contains two basic residues, whereas no charged residues are observed in biochemically characterized MSTs [Fig. 2(B)]2; this may relate to the distinct ionic charge of the respective in vitro substrates, thiosulfate (−2) and 3-mercaptopyruvate (−1). YnjE contains only one charged residue at the last position of its active site loop (Arg390) which is in agreement with the suggestion that an Arg (YnjE Arg390, Av_RhdA Arg235) at this position likely provides stabilization of an active site anion.7

Figure 4.

Comparison of the active sites of YnjE, Av_RhdA and RhodBov. Electrostatic potential maps of the region surrounding the active site. A: YnjE, B: Av_RhdA and C: RhodBov. Electropositive (blue) and electronegative (red) surface potentials were calculated at an ionic strength of 150 mM and are contoured at ±10 kT/e. D: Ribbon representation of a superposition of the active sites and the surrounding active site loops: YnjE (green), RhdA_Av (pdb code 1e0c, purple), B: RhodBov (pdb code 1boi, orange). The active site Cys in its persulfurated form is shown in stick representation in red. E: Stick representation of residues that might be important in catalysis. Left panel: Superposition of YnjE (green) and Av_RhdA (purple). Right panel: Superposition of YnjE (green) and Rhodbov (orange).

Table II.

Kinetic Parameters for E. coli YnjE and Variants of the Six Amino Acid Active Site Loop Measured As Rate of Thiocyanate Formation with Thiosulfate and 3-Mercaptopyruvate as Sulfur Source

| Thiosulfate:cyanide sulfurtransferase activity |

3-mercaptopyruvate:cyanide sulfurtransferase activity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variants | kcat (min−1) | Km (Na2S2O3) (mM) | kcat/Km (Na2S2O3) (min−1 × mM−1) | kcat (min−1) | Km (C3H4O3S) (mM) | kcat/Km (C3H4O3S) (min−1 × mM−1) |

| YnjE-Rhobov | ||||||

| 385CRKGVT390 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 60 ± 8.2 | 0.038 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| YnjE-SseA | ||||||

| 385CGSGVT390 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| YnjE-GlpE | ||||||

| 385CYHGNS390 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 5.4 | 0.035 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| YnjE-PspE | ||||||

| 385CNAGRQ390 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 43 ± 4.8 | 0.035 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| YnjE | ||||||

| Δ1-21 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 57 ± 8.1 | 0.006 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| YnjE | ||||||

| C385A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d., none detectable. Data are the means of at least three independent determinations.

In spite of the clear structural similarities between YnjE and the two structurally characterized tandem-domain rhodaneses Av_RhdA and Rhodbov (rms deviations of 1.67 and 1.75 Å for 247 and 248 residues, respectively), the superposition of the structures reveals significant differences in several regions around the active site, such as additional loops or variations in loop lengths [Fig. 4(D)]. As a result, the shape of the protein surface in proximity of the active site is different among the three enzymes reinforcing earlier notions that insertions/extensions of active site loops generate the required substrate selectivity.21,23

A conserved feature of the YnjE, Av_RhdA as well as Cdc25 phosphatase structures is a hydrogen bonded salt bridge between the active site loop Arg and a Glu residue (Arg390 and Glu318 in YnjE) [Fig. 4(E)]. The side-chain of Arg390 is well positioned to assist catalysis by engaging in hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge with the incoming negatively charged sulfur donor substrate.21 In Rhobov the guanidinium group of Arg186 is located in a similar position, at a slightly larger distance from the anion binding site, and compensates for the Arg → Thr252 replacement in this enzyme19 [Fig. 4(E)]. Thiosulfate binding to Rhobov has shown that Arg186 and Lys249 provide favorable interactions to the bound anion.24 These and other observations indicate that, in spite of the distinct catalyzed reactions, the enzymes are derived from a common ancestor.5 The active site containing domain of YnjE is more similar to the corresponding domain of Av_RhdA (Z-score = 16.7) than to Rhodbov (Z-score = 10.4) [Fig. 4(E)]. Besides the conserved salt bridge, two additional Arg residues (Arg238 and Arg314 in YnjE) and the active site loop Thr are identical. In addition to the less positively charged active site pocket of YnjE, the major difference, which might be responsible for the different substrate specificity, is YnjE's Tyr326 that is in hydrogen bonding distance to the persulfide and is absent in the Av_RhdA structure. Tyr326 of YnjE is highly conserved in the YnjE triple-domain rhodanese-like protein family.

Site directed mutagenesis of the active site loop of YnjE

As analysis of the sulfurtransferase activity of YnjE Δ1–21 with either 3-mercaptopyruvate or thiosulfate as sulfur donors resulted only in a low activity with thiosulfate (Table II), while at the same time the active site loop resembles more closely those found in 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferases [Fig. 2(B)], we were interested to determine the factors for the different substrate specificities. To analyze whether the six amino acid active site loop is the only determinant for the activity towards either 3-mercapotopyruvate or thio-sulfate as sulfur donor, we altered YnjE: The amino acids present in the active site loop of “classical” Rhobov, CRKGVT, in addition to the amino acid sequence found in two E. coli TSTs, GlpE (CYHGNS) and PspE (CNAGRQ), and, for comparison, the amino acids found in E. coli MST SseA (CGSGVT) were introduced into YnjE [Fig. 2(B)]. Analysis of the activities of the YnjE variants in comparison to an inactive YnjE variant with an exchange in the active site cysteine to alanine (C385A) were determined with either 3-mercaptopyruvate or thiosulfate as substrate. The variants YnjE-Rhobov(385CRKGVT390), YnjE-GlpE(385CYHGNS390), and YnjE-PspE(385CNAGRQ390) with thiosulfate showed a 4 to 6-fold increase in kcat, while the Km was essentially unchanged (Table II). In comparison, the YnjE-SseA(385CGSGVT390) variant was inactive with both thiosulfate and 3-mercaptopyruvate. Also, the variants YnjE-Rhobov(385CRKGVT390), YnjE-GlpE(385CYHGNS390), and YnjE-PspE(385CNAGRQ390) displayed no activity with 3-mercaptopyruvate. The variant YnjE-C385A was completely inactive with all substrates tested, showing that Cys385 is involved in catalysis. As shown by our results, the activity of YnjE could be enhanced towards thiosulfate by a simple exchange of the active site loop found in highly active rhodaneses like Rhobov, GlpE or PspE, however, the total activity still remained low. Thus, the surrounding amino acids of the active site loop are also crucial in determining substrate specificity and turnover. In summary, we conclude from the activity assays and the structural comparisons that YnjE is more similar to a TST than a MST. At the same time the activity data confirm that the active site loop found in rhodaneses is not the only determinant for substrate specificity. At present, the physiological substrate for YnjE remains to be determined and as YnjE was efficiently sulfurated by IscS in vitro, it remains possible that a protein might act as sulfur donor for YnjE in a persulfuration reaction.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

YnjE from Escherichia coli without its putative periplasmic leader sequence (YnjE Δ1-21) was cloned into the pACYC-Duet1 vector (Novagen) using the BamHI and NotI restriction sites, resulting in vector pAU2. YnjE was expressed as an N-terminally His6-tagged protein in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen) by induction at an OD600 = 0.5 with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-thiogalactoside at 30°C for 4 h. The protein was purified by metal affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA, Invitrogen) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 prep grade, GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl. Selenomethionine-labeled protein was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) using methionine-biosynthesis inhibition.25

Site directed mutagenesis of YnjE

By using PCR mutagenesis, amino acid exchanges to the six amino acid active site loop found in Rhobov 385CRKGVT390, E. coli GlpE 385CYHGNS390, E. coli PspE 385CNAGRQ390, E. coli SseA 385CGSGVT390 and the active site cysteine C385A variant were introduced into pAU2.

Sulfuration of YnjE by IscS

IscS was expressed and purified as described earlier.26 The sulfuration of YnjE by IscS was performed under anaerobic conditions inside a glove box (Coy Laboratories) containing less than 2 ppm O2. To remove oxidative modifications at the catalytic cysteine, YnjE was incubated with a 5-fold molar excess of DTT for 2 h on ice, dialyzed over night against 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl and subsequently incubated for 4 h with a 2-fold molar excess of L-cysteine and catalytic amounts of the cysteine desulfurase IscS (0.1-fold molar excess).

Enzyme assays

Thiosulfate/3-mercaptopyruvate:cyanide sulfurtransferase activities of YnjE and variants were measured by the classical colorimetric method after Sörbo,27,28 which is based on the absorbance of the complex formed between a ferric ion and thiocyanate at 460 nm. For activity assays, YnjE and variants were incubated with an excess of DTT to desulfurate the proteins, and the buffer was exchanged by using a PD10 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). Reaction mixtures contained 100 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.6, 1–70 mM sodium thiosulfate/3-mercaptopyruvate, 50 mM potassium cyanide, and 3 μM enzyme in a volume of 0.5 mL. Reactions were started by the addition of KCN. After 10 min, formaldehyde (15% (v/v), 250 μL) was added to quench the reaction. Color was developed by the addition of 750 μL of ferric nitrate reagent [100 g Fe(NO3)3 × 9H2O and 200 mL of 65% (v/v) HNO3 per 1,500 mL]. In all cases, the A460nm was measured against an appropriate blank that was incubated for the same time. Thiocyanate (complexed with iron) was quantified using ε460nm = 4,200M−1 × cm−1. Apparent Km-values for varying thiosulfate concentrations were determined with a constant concentration of potassium cyanide at 50 mM. Enzyme assays were performed with freshly purified protein over a period of 5 days to determine protein stability. The activity of the variants YnjE-Rhobov 385CRKGVT390, YnjE-GlpE 385CYHGNS390, and YnjE-PspE 385CNAGRQ390 was stable and no decrease in kcat was observed after 5 days. In contrast, wild-type YnjE was only active directly after purification, and activity was completely lost after 1 day. The kcat for YnjE wild-type was determined with freshly purified protein.

Crystallization of YnjE

YnjE crystals were grown by vapor diffusion in hanging drops containing equal volumes of protein in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl at a concentration of 10 or 25 mg/mL, and a reservoir solution consisting of 17–21% (w/v) PEG 4000 and 100 mM sodium phosphate citrate buffer pH 5.6 equilibrated against the reservoir solution. Crystals appeared within 2 days and were cryo-protected by soaking in mother liquor containing 10–20% (v/v) glycerol. They belong to space group P6322 with approximate cell dimensions of a = b = 161, c = 173 Å and γ = 120°, and contain two molecules per asymmetric unit (64% solvent content).

Data collection and structure determination

The crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen, and data collection was performed at 100 K. Datasets were collected at beamlines BM14, ID23-1 (ESRF, Grenoble, France) and BL 14.1 (BESSY, Berlin, Germany). A single data set, collected at the Se absorption edge determined by a fluorescence scan of the crystal (0.9792 Å) was used to solve the structure. All data sets were indexed and processed using Moslfm and Scala.29,30 The Se sites were located from the anomalous difference data.31 Phases from SHARP were then combined with the native 2.4 Å data set and extended using Pirate.32 For subsequent calculations, the CCP4 suite was utilized32 with exceptions as indicated. The model was build automatically using Buccaneer.33 The structure was refined with REFMAC5 incorporating TLS refinement in all cycles.34,35 Each monomer was refined separately and solvent molecules were automatically added with Coot.36 Crystals of sulfur-free and persulfurated YnjE were isomorphous and the structure of sulfur-free YnjE was solved by difference Fourier synthesis. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank at RCSB as entries ipo (persulfide) and 3ipp (sulfur-free), respectively. The figures were produced with Pymol, http://www.pymol.org.

Sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were conducted in a Beckman Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) as described.37 Prior to centrifugation, proteins were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) and 200 mM NaCl. Data were analyzed using the c(s) continuous distribution of Lamm equation solutions38 with SEDFIT (www.analyticalultracentrifugation.com). The c(s) analysis was performed with regularization at a confidence level of 0.95 and a floating frictional ratio (f/fo), time-independent noise, baseline, and meniscus position. The c(s) distribution was transformed to the c(M) distribution.

Conclusions

Proteins belonging to the TST family of rhodaneses constitute a highly heterogenous group. Their substrate specificity depends not only on the composition of the active site loop but also on the amino acids found in the surrounding regions. On the basis of active site composition, YnjE is more closely related to the TST rhodaneses, especially to prokaryotic Av_RhdA, in agreement with biochemical data demonstrating a lack of enzyme activity with 3-mercaptopyruvate, even when the active site loop of YnjE has been replaced with one derived from an MST. At the same time phylogenetic studies indicate that YnjE is a prototypical member of a large subfamily of rhodaneses/sulfurtransferases characterized by a highly conserved six amino acid active site loop with the consensus sequence CG[T/S]GWR.

On the basis of the high degree of structural differences found between the prokaryotic Av_RhdA and bovine rhodanese, which has two additional positive charges at the active site entrance, it has been suggested that the TST activity might not represent the only reaction catalyzed by this enzyme family.22 So far, rhodanese-like proteins are only grouped into the TST and MST family, however, this is based only on in vitro activities and might not reflect their real catalytic activities in vivo. In vivo neither substrates nor sulfur acceptors could be clearly identified in any organism so far, a lack that prevents a more thorough understanding of the rhodanese superfamily.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Tim Larson (Virginia Tech) for helpful discussions.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Av_RhdA

Azotobacter vinelandii rhodanese

- MST

3-mercaptopyruvate:cyanide sulfurtransferase

- PEG

polyethylene gycol

- Rhobov

mitochondrial bovine (Bos taurus) rhodanese

- rms

root mean square

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TST

thiosulfate:cyanide sulfurtransferase.

References

- 1.Cipollone R, Ascenzi P, Visca P. Common themes and variations in the rhodanese superfamily. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:51–59. doi: 10.1080/15216540701206859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bordo D, Bork P. The rhodanese/Cdc25 phosphatase superfamily. Sequence-structure-function relations. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:741–746. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller EG, Palenchar PM, Buck CJ. The role of the cysteine residues of ThiI in the generation of 4-thiouridine in tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33588–33595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthies A, Nimtz M, Leimkuhler S. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in humans: identification of a persulfide group in the rhodanese-like domain of MOCS3 by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7912–7920. doi: 10.1021/bi0503448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann K, Bucher P, Kajava AV. A model of Cdc25 phosphatase catalytic domain and Cdk-interaction surface based on the presence of a rhodanese homology domain. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:195–208. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauman EB, Cogswell JP, Lovejoy B, Rocque WJ, Holmes W, Montana VG, Piwnica-Worms H, Rink MJ, Saper MA. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the human cell cycle control phosphatase, Cdc25A. Cell. 1998;93:617–625. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spallarossa A, Donahue JL, Larson TJ, Bolognesi M, Bordo D. Escherichia coli GlpE is a prototype sulfurtransferase for the single-domain rhodanese homology superfamily. Structure. 2001;9:1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe MD, Ahmed F, Lacourciere GM, Lauhon CT, Stadtman TC, Larson TJ. Functional diversity of the rhodanese homology domathe Escherichia coli ybbB gene encodes a selenophosphate-dependent tRNA 2-selenouridine synthase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1801–1809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Yang F, Kang X, Xia B, Jin C. Solution structures and backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli rhodanese PspE in its sulfur-free and persulfide-intermediate forms: implications for the catalytic mechanism of rhodanese. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4377–4385. doi: 10.1021/bi800039n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spallarossa A, Forlani F, Carpen A, Armirotti A, Pagani S, Bolognesi M, Bordo D. The “rhodanese” fold and catalytic mechanism of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferases: crystal structure of SseA from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begley TP, Xi J, Kinsland C, Taylor S, McLafferty F. The enzymology of sulfur activation during thiamin and biotin biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:623–629. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, III, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forlani F, Cereda A, Freuer A, Nimtz M, Leimkühler S, Pagani S. The cysteine-desulfurase IscS promotes the production of the rhodanese RhdA in the persulfurated form. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6786–6790. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holm L, Kaariainen S, Rosenstrom P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2780–2781. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm L, Park J. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:566–567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in postscript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2002 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. Chapter 2:Unit 2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ploegman JH, Drent G, Kalk KH, Hol WG. The structure of bovine liver rhodanese. II. The active site in the sulfur-substituted and the sulfur-free enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1979;127:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alphey MS, Williams RA, Mottram JC, Coombs GH, Hunter WN. The crystal structure of Leishmania major 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. A three-domain architecture with a serine protease-like triad at the active site. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48219–48227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bordo D, Deriu D, Colnaghi R, Carpen A, Pagani S, Bolognesi M. The crystal structure of a sulfurtransferase from Azotobacter vinelandii highlights the evolutionary relationship between the rhodanese and phosphatase enzyme families. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:691–704. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bordo D, Forlani F, Spallarossa A, Colnaghi R, Carpen A, Bolognesi M, Pagani S. A persulfurated cysteine promotes active site reactivity in Azotobacter vinelandii Rhodanese. Biol Chem. 2001;382:1245–1252. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bode W, Huber R. Proteinase-protein inhibitor interaction. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1991;50:437–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lijk LJ, Torfs CA, Kalk KH, De Maeyer MC, Hol WG. Differences in the binding of sulfate, selenate and thiosulfate ions to bovine liver rhodanese, and a description of a binding site for ammonium and sodium ions. An X-ray diffraction study. Eur J Biochem. 1984;142:399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:105–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leimkühler S, Rajagopalan KV. A sulfurtransferase is required in the transfer of cysteine sulfur in the in vitro synthesis of molybdopterin from precursor Z in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22024–22031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorbo B. A colorimetric method for the determination of thiosulfate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957;23:412–416. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthies A, Rajagopalan KV, Mendel RR, Leimkühler S. Evidence for the physiological role of a rhodanese-like protein for the biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5946–5951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308191101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leslie AGW. 1992. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4+ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography No.26.

- 30.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. In: Carter CWJ, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 276. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 472–494. Macromolecular crystallography, part A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey S. The CCP4 suite—programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz J, Chowdhury MM, Hänzelmann P, Nimtz M, Lee EY, Schindelin H, Leimkühler S. The sulfurtransferase activity of Uba4 presents a link between ubiquitin-like protein conjugation and activation of sulfur carrier proteins. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6479–6489. doi: 10.1021/bi800477u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]