Abstract

Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria is a rare autosomal recessive disorder (OMIM #241530), characterized by decreased renal phosphate reabsorption that leads to hypophosphatemia, rickets, and bone pain; hypophosphatemia is believed to stimulate 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D synthesis which, in turn, results in hypercalciuria. Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria is caused by loss-of-function in the type 2c sodium phosphate cotransporter encoded by the SLC34A3 gene. This report shows a family with a non-previously identified mutation in the SLC34A3 gene and exhibiting mild and different manifestations of HHRH. The probandus had hypophosphatemia, elevated serum 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations, high serum alkaline phosphatase levels, hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis. The other members of the family presented some of these alterations: the mother, hypercalciuria and high 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations; the son, hypercalciuria, high 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D values and elevated alkaline phosphatases; the father, high alkaline phosphatases. The genetic analysis revealed the existence of a single mutation (G78R) in heterozygosis in the SLC34A3 gene in the probandus, her mother and her brother, but not in the father. These findings suggest that he mutation in heterozygosis likely gave rise to a mild phenotype with different penetrance in the three relatives and also indicates that the elevation of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D does not result from hypophosphatemia. Thus, this family raises some issues on the transmission and pathophysiology of hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria.

Background

Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria (HHRH) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder (OMIM #241530), characterized by decreased renal phosphate reabsorption that causes hypophosphatemia, rickets, and bone pain. Hypophosphatemia stimulates the renal 1a-hydrolase, increasing in turn the synthesis and serum levels of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D, with the resultant suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, increased intestinal reabsorption of calcium and hypercalciuria, which differentiates HHRH from autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) and X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH).

Tieder et al. [1] described in 1985 a consanguineous Bedouin kindred in which 6 members had hypophosphatemic rickets and hypercalciuria, probably the same disorder reported by Royer [2] in 1962 as hypercalciuric rickets. Bergwitz et al. [3] performed a genomewide linkage scan combined with homozygosity mapping in the large consanguineous Bedouin kindred reported by Tieder et al [1]. The candidate gene region was narrowed to a 1.6 Mb region on chromosome 9q34, and the mutated gene was identified as the SLC34A3, which encodes the type 2c sodium phosphate cotransporter (NPT2c), that, with the NPT2a, is expressed at the apical domain of renal proximal tubular cells and reabsorb phosphate from the glomerular filtrate under the hormonal control of PTH and the fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) [4-7].

HHRH has been defined as an autosomal recessive disorder because obligate carriers of the mutation, such as the parents of affected children, have borderline hypercalciuria but not hypophosphatemia or rickets [8]. However, because of the low prevalence of the disease, the mode of inheritance has been inferred from a limited number of families worldwide. From its initial description in 1985, few families [1,8-10] and sporadic cases [11-14] have been reported in Turkey, Holland, Morocco, North America, Japan and Germany.

Case report

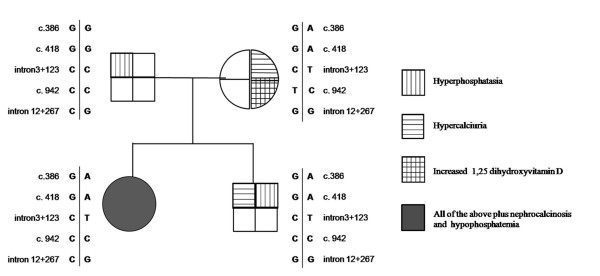

A four member Spanish family is described in this report (Figure 1). Parents were not consanguineous and all members were asymptomatic. The daughter was referred to our outpatient clinic at the age of 11 years for evaluation of hyperphosphatasia and hypercalciuria. She had been suffering of intermittent abdominal pain for 3 years but denied bone pain or renal colic. At the first evaluation her height was 153.3 cm (50th percentile) and her weight 44.5 kg (50th percentile), normal blood pressure (116/60 mm Hg) and the only abnormal finding in the physical examination was a mild dorsal scoliosis. The initial serum biochemistry in our clinic confirmed the previous biochemical alterations and showed decreased tubular reabsorption of phosphate (TRP) and high circulating levels of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D. Acid-base status and serum urea, creatinine, albumin, lipid profile and liver-function tests were normal. Bilateral medullar nephrocalcinosis was found by renal ultrasonography. No radiological signs of rickets were present, bone mineral density was within normal reference values and bone age was according to chronological age. Oral phosphate supplementation was prescribed but only for a short period because of patient's bad compliance and lack of major disease-related manifestations. Significant biochemical findings of the patient and her family are shown in Table 1. Renal ultrasound of the parents and brother were normal. After a 7.5 year follow up, the four family members continue asymptomatic and their initial laboratory alterations remain essentially unchanged.

Figure 1.

Family pedigree showing the haplotypes and analytical findings. In addition to the c.418 G>A mutation, the genotypes for the intron 3+c.123 C>T, exon 8 c.942 T>C, and intron 12+c.267 G>C are also indicated.

Table 1.

Initial/final significant findings in the family

| Patient | Mother | Father | Brother | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 11 | 33 | 41 | 1 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (Times above the upper limit of normal reference values) | 4.0/2.0 | 0.6/1.1 | 2.5/1.5 | 1.5/3.5 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) (Normal reference values: 8.5-10.5) | 10.5/9.8 | 9.46/9.84 | 10.0/8.8 | 10.6/10.3 |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.2/2.3 | 2.6/4.3 | 4.2/2.8 | 5.3/5.0 |

| Urine calcium/creatinine (mg/mg) (Normal reference values: <0.20) | 0.45/0.21 | 0.33/0.27 | 0.17/0.04 | 0.52/0.34 |

| Urine calcium (mg/kg/day) (Normal reference values: < 4.0) | 9/5 | 6.4/NA | 4.5/NA | 5.5-6.2 |

| Urine phosphate (mg/kg/day) (Normal reference values: 12.4 ± 4.6) | 28.0/16.9 | 12.5/NA | 16.1/NA | 28.0/NA |

| Tubular reabsorption of phosphate (%) (Normal reference values: 75-85) | 63.8/74.4 | 79.0/90.5 | 77.8/NA | 78.1/89.9 |

| TmP/GFR (mg/dl) (Normal reference values: 2.5-4.2) | 2.1/1.8 | 2.1/4.2 | 3.3/NA | 4.1/4.9 |

| Serum intact PTH (pg/ml) (Normal reference values:10-65) | 9/22 | 62/27 | 38/41 | 13/13 |

| Serum 25 hydroxivitamin D (ng/ml) (Normal reference values: 10-68) | 16/18 | 18/20.4 | 41/24.2 | 29/29 |

| 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (pg/ml) (Normal reference values: 20-63) | 109/96 | 83/80 | 37/38 | 71/64 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 104/109 | 83/107 | 84/101 | 144/159 |

Normal values for serum phosphorus: < 14 years: 3.5-6.5 mg/dl; Adults: 2.7-4.5 mg/dl. TmP/GFR values were calculated by the Walton Bijvoen nomogram. [16]. eGFR: Estimated glomerular flow rate based on Cockroft-Gault formula for adults and Schwartz formula for children. NA: not available.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institution. The two parents gave their informed consent to participate in the study, including the genetic study of their children. Genomic DNA was obtained from leukocytes in 10 ml of blood, and the 13 coding exons and intronic flanking nucleotides of the SLC34A3 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These PCR fragments were purified and both DNA strands were sequenced on an automated ABI310 system (Applied Biosystems - Applera Corporation, Drive Foster City, CA, USA).

We found a nucleotide change in exon 4 (c.418 G>A) that results in a missense amino acid change, Glycine78Arginine (G78R). This has not been reported as a SLC34A3 polymorphism in the genome database http://www.ensembl.org, and the glycine 78 was conserved among species. The c.418 A created a site for the restriction enzyme PstI (CTGCA/G), giving two fragments of 117 + 354 bp whereas the wild type allele was seen as a single fragment of 471 bp. We confirmed the absence of this putative mutation in 200 healthy controls by digestion of PCR fragment with PstI, followed by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gels. The patient, her mother and her brother were heterozygous for this mutation and the father was wild-type homozygote.

In addition to G78R, the patient was heterozygous for several polymorphisms (Figure 1). The patient was homozygous for a polymorphism in the last nucleotide of exon 8 (c.942 T>C). The patient's mother was heterozygous carrier for this exon 8 variant, while the father and brother were also c.942 C homozygotes. Although this change does not change the amino acid (L253L), in silico analysis with the BDGP program http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html predicts an effect on pre-mRNA splicing as a result of a reduction of the score for the splicing (0.64 vs. 0.54) at the exon 8-intron 8 boundary. Thus, the allele c.942 C might affect splicing, skip exon 8 and produce an aberrant mRNA. To assess the potential effect on splicing, mRNA of the proband, their parents and brother and two healthy donors, was obtained from peripheral leukocytes. The cDNA was synthesized and PCR amplified with primers that matched exons 3 and 9. We were unable to obtain amplified product from any of the cDNAs, including the two controls, and could not determine the putative effect of this variant on pre-mRNA splicing.

Conclusions

This family presents phenotypic and genetic peculiarities that deserve some comments. The mother and her two siblings were heterozygous for a non-previously identified missense mutation in the SLC34A3 gene (c.418 G>A; G78R). The amino acid 78 of NPT2c is conserved among species (glycine) and is located in the first membrane-spanning domain of the cotransporter. The glycine to arginine change likely disrupts the transmembrane domain, resulting in an abnormal transporter channel function responsible for the clinical manifestations. The other nucleotide changes found in these subjects correspond to polymorphisms. Unfortunately, and likely as a result of the low expression of NPT2c in leukocytes, we did not succeed in studying the potential impact of these polymorphisms on RNA splicing. The daughter had nephrocalcinosis, hypophosphatemia, hypercalciuria and elevated serum 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations whereas her mother and brother, in spite of carrying the same G78R mutation, only had hypercalciuria and increased 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D. This indicates either the girl, and likely the father, carried a second mutation out of the region analyzed, for instance, in the promoter or intronic nucleotides that were not sequenced or the mutation in heterozygosis gave rise to a mild phenotype with different penetrance in the three relatives. The last one is the most plausible hypothesis because heterozygous SLC34A3 mutations leading to a variety of biochemical abnormalities have already been reported in previous HHRH families [3]. The elevation of alkaline phosphatases in the father likely corresponds to benign hyperphosphatasemia [15], because of the absence of symptoms and the lack of associated biochemical alterations, although accounted for an additional source of confusion in the interpretation of the clinical picture of the family.

It is also of note that the mother and his son were hypercalciuric and had high levels of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D, particularly the mother, in the presence of normal serum concentrations of phosphate. This challenges the pathophysiological concept that in HHRH hypophosphatemia triggers the increased production of 1,25 dydroxyvitamin D which, in turn, causes hypercalciuria. Our findings support the relationship between elevations of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D and urinary calcium but not the hypophosphatemia as the primary event responsible for these alterations. It could be hypothesized that downregulation of FGF23 serum levels, due to decreased phosphate reabsorption, could explain, at least partly, the elevation of the 1-25 vitamin D. Unfortunately, FGF23 was not measured.

In summary, this report describes an additional family with HHRH, finds a new mutation in the SLC34A3 gene and, more interestingly, raises some issues on the genetic basis of this disease and its pathophysiological mechanism.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FS and MTPM were responsible for the diagnosis and clinical follow-up of this family. NMG and HGP wrote down the first draft of the manuscript. HGP and EC carried out the molecular genetic studies. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Natalia Mejia-Gaviria, Email: namega@hotmail.com.

Helena Gil-Peña, Email: helenagp@ficyt.es.

Eliecer Coto, Email: eliecer.coto@sespa.princast.es.

Teresa M Pérez-Menéndez, Email: materepere@yahoo.es.

Fernando Santos, Email: fsantos@uniovi.es.

Acknowledgements

Partly supported by a research grant from Fundación Nutrición y Crecimiento. The study was completed during a sabbatical leave of N Mejia-Gaviria funded with a grant of the Spanish Society of Nephrology.

References

- Tieder M, Modai D, Samuel R, Arie R, Halabe A, Bab I, Gabizon D, Liberman UA. Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:611–617. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503073121003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer P, Mathieu H, Gerbeaux S, Frederich A, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Dartois AM, Cuisinier P. Idiopathic hypercalciuria with nanism and renal involvement in children. Ann Pediatr (Paris) 1962;9:147–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergwitz C, Roslin NM, Tieder M, Loredo-Osti JC, Bastepe M, Abu-Zahra H, Frappier D, Burkett K, Carpenter TO, Anderson D, Garabedian M, Sermet I, Fujiwara TM, Morgan K, Tenenhouse HS, Juppner H. SLC34A3 mutations in patients with hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria predict a key role for the sodium-phosphate cotransporter NaPi-IIc in maintaining phosphate homeostasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:179–192. doi: 10.1086/499409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segawa H, Kaneko I, Takahashi A, Kuwahata M, Ito M, Ohkido I, Tatsumi S, Miyamoto K. Growth-related renal type II Na/Pi cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19665–19672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster IC, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. Proximal tubular handling of phosphate: A molecular perspective. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1548–1559. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhouse HS. Phosphate transport: Molecular basis, regulation and pathophysiology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murer H, Hernando N, Forster I, Biber J. Proximal tubular phosphate reabsortion: Molecular Mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1373–1409. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Eckstein G, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y, Wagenstaller J, Tiosano D, Gershoni-Baruch R, Albers N, Lichtner P, Schnabel D, Hochberg Z, Strom TM. Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria is caused by mutations in the sodium-phosphate cotransporter gene SLC34A3. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:193–201. doi: 10.1086/499410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieder M, Modai D, Shaked U, Samuel R, Arie R, Halabe A, Maor J, Weissgarten J, Averbukh Z, Cohen N, Edelstein S, Liberman UA. 'Idiopathic' hypercalciuria and hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets: two phenotypical expressions of a common genetic defect. New Eng J Med. 1987;316:125–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701153160302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuvel L van de, de Koul KO, Knots E, Knoers N, Monnens L. Autosomal recessive hypophosphataemic rickets with hypercalciuria is not caused by mutations in the type II renal sodium/phosphate cotransport gene. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:48–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremke B, Bergwitz C, Ahrens W, Schütt S, Schumacher M, Wagner V, Holterhus PM, Jüppner H, Hiort O. Hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria due to mutation in SLC34A3/NaPi-IIc can be masked by vitamin D deficiency and can be associated with renal calcifications. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:49–56. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Aichaoui S, Bahiri R, Mahfoud S, Benbouazza K, Guédira N, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:481–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Sorenson AH, Imel EA, Friedman NE, Gertner JM, Econs MJ. Intronic deletions in the SLC34A3 gene cause hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4022–4027. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaureguiberry G, Carpenter TO, Forman S, Jüppner H, Bergwitz C. A novel missense mutation in SLC34A3 that causes hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria in humans identifies threonine 137 as an important determinant of sodium-phosphate cotransport in NaPi-IIc. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:369–370. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00090.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JW. Inherited elevation of alkaline phosphatase activity in the absence of disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:983–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197911013011806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton RJ, Bijvoet OL. Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975;16(2):309–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92736-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]