Abstract

Mice are an excellent model for studying mammalian hearing and transgenic mouse models of human hearing, loss are commonly available. However, the mouse cochlea is substantially smaller than other animal models routinely used to study cochlear physiology. This makes study of their hair cells difficult. We develop a novel methodology to optically image calcium within living hair cells left undisturbed within the excised mouse cochlea. Fresh cochleae are harvested, left intact within their otic capsule bone, and fixed in a recording chamber. The bone overlying the cochlear epithelium is opened and Reissner’s membrane is incised. A fluorescent calcium indicator is applied to the preparation. A custom-built upright two-photon microscope was used to image the preparation using 3-D scanning. We are able to image about one third of a cochlear turn simultaneously, in either the apical or basal regions. Within one hour of animal sacrifice, we find that outer hair cells demonstrate increased fluorescence compared with surrounding supporting cells. This methodology is then used to visualize hair cell calcium changes during mechanotransduction over a region of the epithelium. Because the epithelium is left within the cochlea, dissection trauma is minimized and artifactual changes in hair cell physiology are expected to be reduced.

Keywords: cochlea, calcium image, two-photon microscopy, transduction, hearing

Introduction

The process of mammalian hearing is initiated when an incoming sound pressure wave enters the ear canal and vibrates the eardrum. These vibrations are transmitted sequentially through three middle ear bones (malleus, incus, and stapes) to the inner ear. The cochlea is the portion of the inner ear responsible for the sense of hearing. Vibration of the stapes, which sits within the oval window of the cochlea, creates a traveling wave that propagates along the cochlear duct and stimulates the region of the cochlea tuned to the corresponding frequency.1 Hair cells at that location transduce the mechanical sound pressure waves into electrical signals. Deflection of the hair cell stereociliary bundles by the cochlear traveling wave opens mechanosensitive channels and allows the entry of cations (predominantly K+ and Ca2+) into the hair cell.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The electrical signals are then transmitted to the auditory nerve where they are carried to the brain for processing.

Nonmammalian hair cells have historically been used to study mechanotransduction, the conversion of mechanical into electrical energy, because of the ease of dissection.7, 8, 9 However, mammalian and nonmammalian hair cells have different electrical characteristics.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Also, the mammalian cochlea is more sensitive to and can better differentiate between sounds close in frequency than nonmammalian species. This is because outer hair cells, which are unique to the mammalian cochlea, produce forces that improve hearing sensitivity and frequency selectivity. This process is called the cochlear amplifier, and both somatic electromotility and stereociliary force production have been proposed as the underlying basis.16, 17, 18, 19 Importantly, outer hair cells are typically the first cell type to be lost after noise exposure, ototoxic drug exposure, and with aging. Thus, the study of nonmammalian hair cells is not necessarily representative of what is happening within the mammalian cochlea.

Mice can be used to study mammalian hearing in an effort to understand human disease. Mice have cochlear anatomy and auditory characteristics similar to humans. They are easy and inexpensive to maintain and breed, and their time to maturity is short. Most importantly, inbred species of mice are commonly available. This includes transgenic mice that have genetic mutations that cause human hearing loss. A major difficulty in studying the mouse cochlea, however, is that it is quite small. The size of the cochlea is only ∼1.5 mm in diameter, and the hair cells are also smaller than those of most other mammals. For this reason, the guinea pig, gerbil, and chinchilla have often been used to study hair cell physiology. However, these species do not have the genetic and cost advantages of mice.

We describe a novel methodology we developed to study sound transduction by outer hair cells (OHCs) left undisturbed within an excised mouse cochlear preparation. Mechanosensitive channels in hair cell stereocilia permit the entry of calcium and potassium, which leads to cell depolarization. This opens voltage-gated calcium channels along the basolateral surfaces of the hair cell. Thus, measuring the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]) provides an assessment of sound transduction. The fluorescence intensity of ion-sensitive dyes is related to the concentration of the ions, and thus can be used to detect ion concentration changes inside of cells. In our experiments, we have used Oregon Green BAPTA 488-AM, a fluorescent indicator that is sensitive to the calcium concentration. Previously, it has been widely used in the imaging of activity within nerve cells.20, 21, 22 For our purposes, we have used it to image the intracellular calcium concentration within OHCs using two-photon microscopy. During the imaging process, mechanical stimulation of the stapes at acoustic frequencies was performed to elicit hair cell transduction. We found that the stimulus produced reversible increases in OHC calcium concentration.

Materials and Methods

Specimen Preparation

The care and use of the animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine. We used wild-type adult mice of mixed background that were 4 to 6 weeks old. The mouse was anesthetized with a ketamine∕xylazine mixture and decapitated. Both cochleae were harvested and placed into oxygenated extracellular solution. The extracellular solution was similar to perilymph, the fluid that bathes the basolateral surfaces of the hair cells. However, we increased the calcium concentration within it to evoke larger responses. The extracellular solution contained 142 mM of NaCl, 4 mM of KCl, 10 mM of glucose, 10 mM of HEPES, and 4 mM of CaCl2. The pH value of the solution was adjusted to between 7.35 and 7.40, and the osmolality of the solution was ∼305 mOsm∕kg.

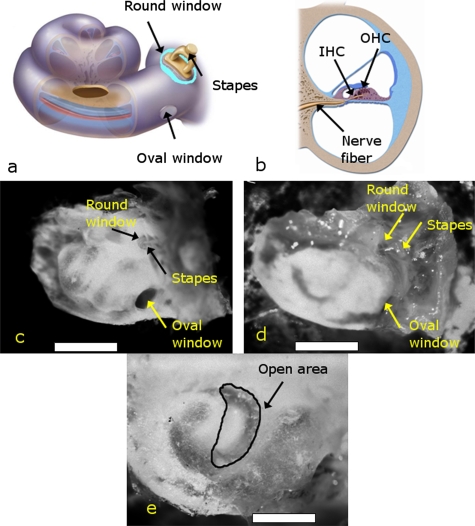

The cochlea was microdissected from the surrounding bone and tissue under a stereo microscope (Stemi-2000C, Zeiss). Figure 1a shows a schematic of the dissected cochlea, and Fig. 1b shows a schematic of a cross section of one turn of the cochlea. Figures 1d, 1e show a mouse cochlea during dissection as imaged through a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera connected to the trinocular port of the microscope. The stapes was left attached to the oval window and the round window was untouched. Then, the cochlea was glued upright into a custom-made plexiglass chamber using dental glue (Iso-Dent, Ellman International, Oceanside, New York). Particular care was taken to make sure the stapes and round window were not contacted by the glue, which might affect their ability to conduct sound. The bone overlying the region of the cochlear epithelium to be studied was then opened with a fine knife and pick. The spiral ligament was gently displaced laterally, and Reissner’s membrane was incised to expose the cochlear epithelium containing the hair cells. Typically about one quarter to one third of a cochlear turn was exposed.

Figure 1.

Dissection of the mouse cochlea. (a) Schematic of the cochlea after dissection. An opening overlying the basal turn of the cochlea (i.e., near the stapes and round window) is shown in this example. (b) Schematic of a cross section of one turn of the cochlea. (c) The entire temporal bone, which contains the cochlea, is shown submerged in extracellular solution after removal from the skull, as visualized through the dissecting microscope. The round window, oval window, and stapes can be seen. The scale bar is 1 mm. (d) The cochlea has been glued upright into a recording chamber, so that only the cochlea (white area to the left of the oval and round windows) is visible. Particular care needs to be taken to leave the round window, oval window, and stapes unencumbered by glue. The scale bar is 1 mm. (e) The apical turn of the cochlea has been opened. This permits visualization of the cochlear epithelium where the hair cells are located (curved dark area at tip of arrow). About one third to one half of a cochlea turn can be opened. The scale bar is 0.5 mm.

The entire dissection process could be completed typically within about 20 min after animal sacrifice. After the dissection, the calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA 488-AM (10 μM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) was applied to the preparation, and the chamber was placed in a dark box for 30 min with a constant flow of oxygen over it. The chamber was then moved to the microscope for imaging, residual dye was rinsed away, and constant perfusion with oxygenated extracellular solution was performed by a peristaltic pump. The pump speed was limited to make sure the flow of extracellular solution did not disturb the optical image.

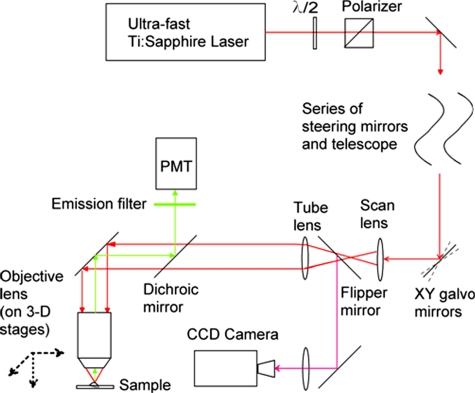

Imaging setup

Imaging was performed using a custom-built upright microscope (Fig. 2) based on a moveable objective microscope (MOM, Sutter Instruments, Novato, California). An objective lens turret (OT1, Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) was inserted to permit easy changing of the objective without losing the orientation of the sample. A CCD camera was incorporated into the setup to allow visualization of the specimen using transmitted light. We typically used a 4× long-working distance objective (Plan Fluor, Nikon) to find the area of interest on the sample. The focal plane and choice of region to image could be varied by moving the objective lens, which was mounted on 3-D translation motor stages (MP285-3Z∕M, Sutter Instruments). Then, we rotated in a 20×, 0.95-NA water immersion lens (XFLUOR 20× water immersion lens, Olympus) objective, which was used for imaging.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the microscope system.

An ultrafast Ti:saphpire laser (Chameleon, Coherent, Palestine, Texas) was used as a near-infrared (NIR) two-photon excitation light source. The center wavelength used in these experiments was 800 nm and the pulse width at the laser output was ∼140 fs. After a series of steering mirrors and telescopes, the laser was adjusted to a suitable beam size and angularly scanned by a pair of 3-mm-aperture galvometer-controlled mirrors (6200H, Cambridge Technology, Lexington, Massachusetts). The scan mirrors were imaged onto the back focal plane of the objective lens by the scan and tube lenses. The laser was focused into sample through the imaging objective. The average laser power was manually attenuated by a half-wave plate and polarizer to about 30 to 40 mW (as measured after passing through the objective lens) to minimize damage to the sample and photobleaching of the indicator, while still providing an adequate signal-to-noise ratio.

The fluorescence light was collected by the same objective lens and reflected to the detector by a dichroic mirror (type ET670SP-2P8, Chroma Technology, Rockingham, Vermont) located between the objective and tube lenses. A bandpass fluorescence filter (type ET525∕50 nm, Chroma Technology) before the detector blocked the residue reflected or scattered NIR excitation light and only let the green fluorescence pass through. The fluorescence light signal was detected by a photomultiplier tube (C7319, Hamamatsu) and digitalized by an A∕D converter (PXI 6259, National Instrument, Austin, Texas).

Open source software (ScanImage Version 3.1, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York)23 written in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts) was used to control the devices and collected images. We intensively modified the software to work with the hardware we used and our experimental protocols. Experimental data images were saved in tagged image file format (TIFF).

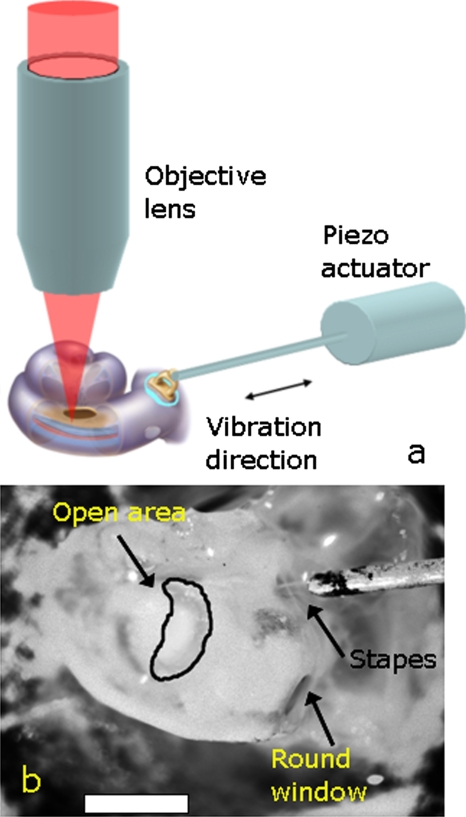

Stimulus

Experiments were performed using a piezoelectric actuator (PA8-12, Piezosystem, Jena, Germany) to generate movements of the stapes as previously described.24 Briefly, the piezoelectric actuator drives a long thin shaft (a 4-cm-long tungsten wire, 0.005 in. diameter). The piezoelectric actuator and shaft were mounted on a 3-D manipulator (PCS-5000 series, Burleigh, EXFO, Mississauga, Ontario) and the tip of the shaft was positioned to contact the stapes. During the collection of a series of images, the piezoelectric actuator produced sound stimuli that varied from 5 to 12 kHz. The stimulus was 15 s long, and consisted of 150-ms blocks of sine waves repeated at a rate of 5 Hz. The magnitude of stapes motion had been previously measured (using a laser Doppler vibrometer) to be in the nanometer range, recreating a sound intensity of ∼80-dB sound pressure level.24 Figure 3a shows a schematic of the experiment setup. Figure 3b shows a microscopic picture of the stimulator tip in contact with the stapes.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the experiment setup. The size of the cochlea is exaggerated for clarity. In this diagram, the opening in the cochlea is shown overlying the basal turn. (b) Image of the preparation taken through the experimental microscope with the tip of the piezoactuator in contact with the stapes. The opening of the cochlea was over the apical turn in this example. The scale bar is 1 mm.

Results

Outer Hair Cell Calcium Imaging

When the preparation was ready for imaging, the recording chamber was transferred to the microscope and held fixed in place on a rigid column. First, the sample was visualized using transmitted light that originated from underneath the sample. We used a 4× objective lens to position the tip of the stimulating probe against the top of the stapes (the capitulum). The angle of approach was within 25 deg of colinearity with the stapes to maximize the transmission of the vibrations of the piezoactuator to the fluids of the cochlea. We then found a region of the cochlear epithelium to image, and changed to the 20× objective lens. Again, the sample was viewed using transmitted light to verify that the OHCs in the region to be imaged appeared organized and healthy. The microscope was then switched into two-photon mode by moving the flipper mirror to allow the laser to reach the sample.

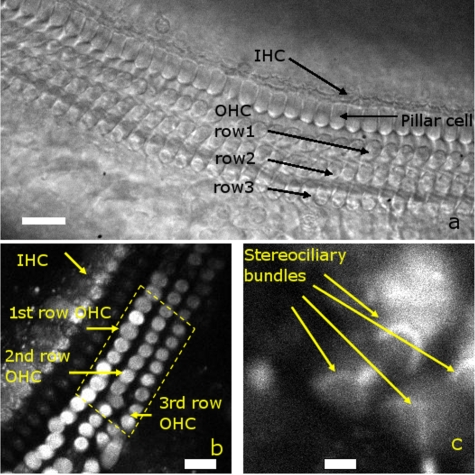

Figure 4a shows typical transmitted light and Figs. 4b, 4c show fluorescence images of the cochlear epithelium. The quality of images depended on the intensity of the laser, the scanning resolution, and the number of averaged frames. While this calcium indicator is expected to partition relatively evenly among all cells, the OHCs always demonstrated the largest fluorescence intensity. This suggests that the indicator is either preferably taken up into OHCs, or that intracellular calcium concentration within OHCs is elevated. The latter is more likely, given the well-known fact that OHCs progressively deteriorate after animal sacrifice and are dead within about four hours. There was some variability in the brightness of different OHCs as well, presumably reflecting differences in their resting intracellular [Ca+2].

Figure 4.

Transmitted light view of the cochlear epithelium as imaged by the CCD camera. The one row of inner hair cells (IHCs) and three rows of outer hair cells (OHCs) can be seen. The pillar cells sit between the IHCs and OHCs. (b) A typical fluorescence image of the cochlear epithelium after staining with the calcium indicator Oregon Green BAPTA 488-AM. The OHCs demonstrate particularly high fluorescence intensity. The dotted line indicates the OHC region from which the total fluorescence was calculated. The scale bar is 15 μm. (c) By increasing the zoom factor, OHC stereociliary bundles can be noted. The scale bar is 5 μm. (a), (b), and (c) are from different samples.

Inner hair cells (IHCs) and some supporting cells, like pillar cells, also could be visualized, but their staining intensity was weaker. Increasing the scanning zoom factor permitted visualization of the V-shaped OHC stereociliary bundles, as in Fig. 4c. We could not distinguish individual OHC stereocilia with this preparation. OHC stereocilia are ∼200 nm in diameter, which is beyond the resolution limit of the light wavelength we used. The staining intensity of the stereocilia was faint compared to that of the soma.

Quantification of Outer Hair Cell Intracellular Calcium Concentration

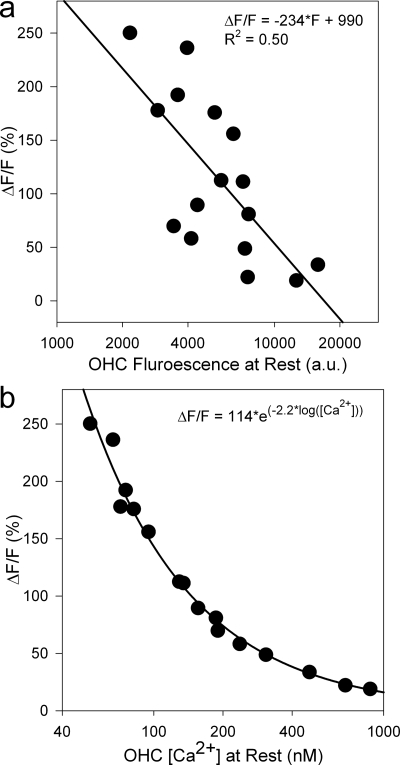

To estimate the resting [Ca2+] inside the OHCs, we measured the calcium indicator fluorescence within 16 OHCs using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland). We selected individual OHCs from four cochleae before and after applying 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 s. This procedure permeabilized the plasma membrane and allowed extracellular calcium to enter into the cell. The average increase in ΔF∕F was 115±19% (mean±SEM, p<0.0001), and varied depending on the initial fluorescence level of the OHC [Fig. 5a]. Although cells that were brighter at rest demonstrated a lower increase in fluorescence after the application of Triton X-100 than those that were initially dimmer, all cells still demonstrated increases in ΔF∕F. This indicated that the calcium indicator was not saturated at the resting [Ca+2] inside the OHCs.

Figure 5.

Change in fluorescence after membrane permeablization vs the initial OHC fluorescence. OHCs that were initially dimmer demonstrated a larger increase in their fluorescence as expected. Data were fitted with a line. (b) Change in fluorescence after membrane permeablization vs the initial OHC [Ca2+]. Data were fitted with an exponential curve. Three data points at the extreme high range were >2 SD above the mean, and were excluded from the calculations of the average resting OHC [Ca2+].

We then calculated the [Ca2+] within the cells using the equation per the instructions provided by the manufacturer of the indicator (Long-Wavelength Calcium Indicators Product Information, Invitrogen). This required knowing the fluorescence at rest, the fluorescence of the calcium saturated probe as determined by the permeabilization experiment, the background fluorescence, and the dissociation constant (Kd) of the indicator dye (170 nM). From our sample, the OHC resting [Ca+2] was found to vary from 52 to 875 nM. After excluding the three OHCs whose [Ca+2] were >2 SD above the mean, the average OHC intracellular [Ca+2] was 137±21 nM (mean±SEM). Figure 5b demonstrates that the ΔF∕F after Triton X-100 application varied exponentially with the resting intracellular [Ca+2].

Outer Hair Cell Fluorescence Change During Sound Stimulation

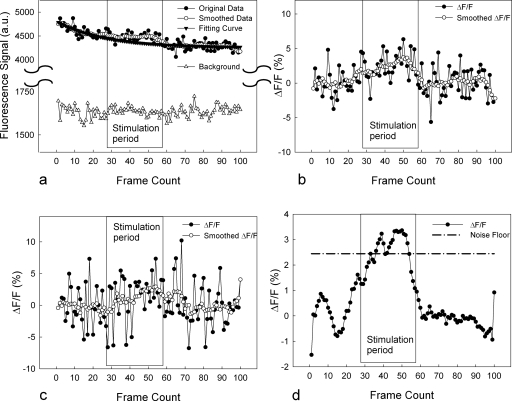

Our goal was to measure changes in intracellular calcium as an assessment of mechanotransduction. This was done by recording a series of 2-D image frames (100 images in ∼60 s). No frame averaging was used for this process. During a portion of the recording, the sound stimulus was applied to the stapes.

Using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland), we selected the OHC region of the epithelium and calculated the mean fluorescence intensity for each image frame. This value was plotted as a function of time. Due to photobleaching, the fluorescence intensity decreased during the time of data collection. This was accounted for by fitting the fluorescence data with a decreasing single exponential curve. The weight function of the fitting was adjusted to remove the effect of sound stimulation from the photobleaching background curve. For frames without any stimulus presented, the weighting was set to one, and for frames where there was a sound stimulus presented, the weighting was set to zero. Then, all the raw data were normalized by the fitted background curve.

Figures 6a, 6b show typical OHC calcium fluorescence intensity curves as a function of time (image frame count number). These examples were collected from the group of 24 OHCs within the apical turn of the cochlea (eight from each of the three rows) from Fig. 4b. Figure 6a demonstrates the original data, the smoothed data, the fitted exponential, and background noise. The sound stimulus was presented between frames 27 through 58. The smoothing method was a moving window average with a nine-point span. In contrast to the fluorescence of the OHCs, the background noise was not affected by photobleaching or the sound stimulus. Figure 6b displays the normalized data (ΔF∕F) and the smoothed normalized data. An increase of the fluorescence intensity of up to 4% over baseline can be seen in the figure during the time of sound stimulation. This is consistent with an increase in intracellular calcium during sound transduction.

Figure 6.

Original data, smoothed data, and exponential fit, as a function of time (frame counts) from a group of 24 OHCs. The smoothing method was a moving window average with a nine-point span. The fit was a single exponential curve, excluding data during the time of the sound stimulus. Sound stimulation was presented between frames 27 and 58, as indicated by the rectangle. Background noise was not affected by photobleaching or the sound. (b) Original data and smoothed data after normalization to the exponential fit for the data shown in (a). (c) Representative response from a single OHC. (d) Average of responses from ten OHCs from six different cochleae. The noise floor threshold shown is 3 SD above average.

In addition to allowing the measurement of responses from groups of OHCs, this technique also permitted the measurement of calcium changes within single OHCs. Figure 6c demonstrates the ΔF∕F response of a single representative OHC. We then measured responses from six different cochleae, and averaged the responses of ten representative cells, as shown in Fig. 6d. The noise floor threshold line is the mean noise floor plus three times the standard deviation, indicating that the response reaches statistical significance. This average change of ∼3% would correspond to a change in the intracellular [Ca+2] of ∼4 to 5 nM.

As an additional control, we also tested six cochleae without sound stimulation, and no change in ΔF∕F was found after adjusting for photobleaching (data not shown).

Discussion

We demonstrate a novel technique to image dynamic changes in calcium within hair cells of the mammalian cochlea. Using two-photon microscopy, we were able to detect changes in OHC calcium concentration during sound stimulation of the cochlea. The slow increase in the fluorescence intensity during the stimulus was consistent with cation entry through mechanosensitive transduction channels in the stereociliary bundles, as well as activation of voltage-gated calcium channels along the basolateral surfaces of the OHC.25, 26, 27 This calcium response corresponds with the summating potential, a slow depolarization within hair cells that can be measured during sound stimulation.28, 29, 30 The average value for the resting [Ca+2] in OHCs that we measured (137±21 nM) was similar to that of other reports studying freshly isolated OHCs from the guinea pig (102±15 nM31 and 181±24 nM32).

There are certainly considerations one must appreciate when interpreting these results. While the cochlea is normally enclosed with the otic capsule bone, we did have to open it to visualize the hair cells. This is expected to partially alter the structural properties of the cochlea and change the acoustic impedance. This may decrease the efficiency of sound propagation through the cochlea. Also, result, hair cell stimulation might be decreased. As well, in a living animal the potential of the endolymph (the fluid bathing the stereocilia of the OHCs) is around +100 mV and the intracellular potential of the OHC is about −70 mV. Once the cochlea was excised for these experiments, the endolymphatic potential dropped to ground potential, reducing the driving potential for cation entry into the hair cell substantially. We partially compensated for this by increasing the extracellular calcium concentration, but nevertheless, this is not a normal physiological environment. Changing the calcium concentration from its normally low level of ∼20 μM can alter the anatomy of the tectorial membrane (TM). However, in the mouse, changes in the length and thickness of the TM when changing from endolymph to perilymph (i.e., high K+ to high Na+, and Ca2+ from 20 μM to2 mM) are only 1 to 2%.33 In addition, the mouse TM does not change in a cross sectional area when the [Ca2+] in perilymph is changed from 2 mM to 20 μM.34

To date, the study of mammalian hair cell forward transduction has been essentially limited to in vivo studies of hearing in anesthetized animals and single-cell patch clamp studies. Both have substantial limitations and inherent difficulties that make data interpretation complex. This technique provides a unique approach to studying regional and genetic differences between cochlear hair cell transduction. In particular, we propose that it will permit the measurement of OHC responses to sound stimuli at different regions of the cochlea and the assessment of functional differences in hair cell physiology between different transgenic mice strains. Thus, we argue that this technique can be used to provide a novel assessment of hair cell stimulation patterns in mice with hearing loss mutations.

Conclusion

The calcium sensitive fluorescence dye, Oregon Green BAPTA 488-AM, successfully entered mammalian OHCs. Two-photon calcium imaging of the mouse cochlear epithelium is used to measure changes in intracellular calcium concentration within OHCs in response to sound stimulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank William E. Brownell and Anping Xia for helpful advice, and Jessica Tao and Haiying Liu for technical support. The artwork is by Scott Weldon. This project was funded by NIDCD K08 DC006671 and The Clayton Foundation (Oghalai).

References

- von Bekesy G., Experiments in Hearing, McGraw-Hill, New Work: (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Corey D. P. and Hudspeth A. J., “Ionic basis of the receptor potential in a vertebrate hair cell,” Nature (London) 281(5733), 675–677 (1979). 10.1038/281675a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W., Holt J. R., Shepherd G. M., and Corey D. P., “Calcium imaging of single stereocilia in hair cells: localization of transduction channels at both ends of tip links,” Neuron 15(6), 1311–1321 (1995). 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin E. A. and Hudspeth A. J., “Detection of Ca2+ entry through mechanosensitive channels localizes the site of mechanoelectrical transduction in hair cells,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92(22), 10297–10301 (1995). 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin E. A. and Hudspeth A. J., “Regulation of free Ca2+ concentration in hair-cell stereocilia,” J. Neurosci. 18(16), 6300–6318 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin E. A., Marquis R. E., and Hudspeth A. J., “The selectivity of the hair cell’s mechanoelectrical-transduction channel promotes Ca2+ at low Ca2+ concentrations,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94(20), 10997–11002 (1997). 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettiplace R. and Fuchs P. A., “Mechanisms of hair cell tuning,” Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61, 809–834 (1999). 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J., Roberts W. M., and Hudspeth A. J., “Mechanoelectrical transduction by hair cells,” Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 17, 99–124 (1988). 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.000531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth A. J. and Jacobs R., “Stereocilia mediate transduction in vertebrate hair cells (auditory system/cilium/vestibular system),” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76(3), 1506–1509 (1979). 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Art J. J., Crawford A. C., and Fettiplace R., “Electrical resonance and membrane currents in turtle cochlear hair cells,” Hear. Res. 22, 31–36 (1986). 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90073-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. C. and Fettiplace R., “Ringing responses in cochlear hair cells of the turtle,” J. Physiol. (London) 284, 120P–122P (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. C. and Fettiplace R., “Non-linearities in the responses of turtle hair cells,” J. Physiol. (London) 315, 317–338 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. C. and Fettiplace R., “An electrical tuning mechanism in turtle cochlear hair cells,” J. Physiol. (London) 312, 377–412 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oghalai J. S., Holt J. R., Nakagawa T., Jung T. M., Coker N. J., Jenkins H. A., Eatock R. A., and Brownell W. E., “Ionic currents and electromotility in inner ear hair cells from humans,” J. Neurophysiol. 79(4), 2235–2239 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oghalai J. S., Holt J. R., Nakagawa T., Jung T. M., Coker N. J., Jenkins H. A., Eatock R. A., and Brownell W. E., “Harvesting human hair cells,” Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 109(1), 9–16 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci A., “Active hair bundle movements and the cochlear amplifier,” J. Am. Acad. Audiol 14(6), 325–338 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell W. E., Bader C. R., Bertrand D., and de Ribaupierre Y., “Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells,” Science 227(4683), 194–196 (1985). 10.1126/science.3966153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. K. and Hudspeth A. J., “Ca(2+) current-driven nonlinear amplification by the mammalian cochlea in vitro,” Nat. Neurosci. 8(2), 149–155 (2005). 10.1038/nn1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oghalai J. S., “The cochlear amplifier: augmentation of the traveling wave within the inner ear,” Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 12(5), 431–438 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. D., Kelleher K., Fink R., and Saggau P., “Three-dimensional random access multiphoton microscopy for functional imaging of neuronal activity,” Nat. Neurosci. 11(6), 713–720 (2008). 10.1038/nn.2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losavio B. E., Reddy G. D., Colbert C. M., Kakadiaris I. A., and Saggau P., “Combining optical imaging and computational modeling to analyze structure and function of living neurons,” Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 1, 668–670 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iyer V., Hoogland T. M., and Saggau P., “Fast functional imaging of single neurons using random-access multiphoton (RAMP) microscopy,” J. Neurophysiol. 95(1), 535–545 (2006). 10.1152/jn.00865.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pologruto T. A., Sabatini B. L., and Svoboda K., “ScanImage: flexible software for operating laser scanning microscopes,” Biomed. Eng. Online 2, 13 (2003). 10.1186/1475-925X-2-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia A., Visosky A. M., Cho J. H., Tsai M. J., Pereira F. A., and Oghalai J. S., “Altered traveling wave propagation and reduced endocochlear potential associated with cochlear dysplasia in the BETA2/NeuroD1 null mouse,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 8(4), 447–463 (2007). 10.1007/s10162-007-0092-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eatock R. A., Fay R. R., and Popper A. N., “Vertebrate hair cells,” in Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, vol. 27, Springer, New York: (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Eatock R. A., Hurley K. M., and Vollrath M. A., “Mechanoelectrical and voltage-gated ion channels in mammalian vestibular hair cells,” Audiol. Neuro-Otol. 7(1), 31–35 (2002). 10.1159/000046860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eatock R. A. and Hutzler M. J., “Ionic currents of mammalian vestibular hair cells,” Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 656, 58–74 (1992). 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P., Cheatham M. A., and Ferraro J., “Cochlear mechanics, nonlinearities, and cochlear potentials,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. 55(3), 597–605 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P., Schoeny Z. G., and Cheatham M. A., “Cochlear summating potentials: composition,” Science 170(958), 641–644 (1970). 10.1126/science.170.3958.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P., “Cochlear physiology,” Annu. Rev. Physiol. 32, 153–190 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K., Saito Y., Nishiyama A., and Takasaka T., “Effects of pH on intracellular calcium levels in isolated cochlear outer hair cells of guinea pigs,” Am. J. Physiol. 261(2 Pt 1), C231–236 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szucs A., Szappanos H., Batta T. J., Toth A., Szigeti G. P., Panyi G., Csernoch L., and Sziklai I., “Changes in purinoceptor distribution and intracellular calcium levels following noise exposure in the outer hair cells of the guinea pig,” J. Membr. Biol. 213(3), 135–141 (2006). 10.1007/s00232-006-0045-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D. M., Freeman D. M., and Weiss T. F., “The osmotic response of the isolated, unfixed mouse tectorial membrane to isosmotic solutions: effect of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ concentrati,” Hear. Res. 87(1–2), 187–207 (1995). 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00089-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge R. M., Evans B. N., Pearce M., Richter C. P., Hu X., and Dallos P., “Morphology of the unfixed cochlea,” Hear. Res. 124(1–2), 1–16 (1998). 10.1016/S0378-5955(98)00090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]