Abstract

Objectives

The objectives were to: (1) document correlations among facility provision (availability and adequacy) in elementary schools, child sociodemographic factors, and school characteristics nationwide; and (2) investigate whether facility provision is associated with physical education (PE) time, recess time, and obesity trajectory.

Methods

The analytic sample included 8935 fifth graders from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey Kindergarten Cohort. School teachers and administrators were surveyed about facility provision, PE, and recess time in April 2004. Multivariate linear and logistic regressions that accounted for the nesting of children within schools were used.

Results

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds were more likely to attend a school with worse gymnasium and playground provision. Gymnasium availability was associated with an additional 8.3 min overall and at least an additional 25 min of PE per week for schools in humid climate zones. These figures represent 10.8 and 32.5%, respectively, of the average time spent in PE. No significant findings were obtained for gymnasium and playground adequacy in relation to PE and recess time, and facility provision in relation to obesity trajectory.

Conclusions

Poor facility provision is a potential barrier for school physical activity programs and facility provision is lower in schools that most need them: urban, high minority, and high enrollment schools.

Keywords: School, Exercise, Sports, Child, Obesity

Introduction

The role of physical activity in obesity prevention is well established, but less than half of children meet national recommendations (Troiano et al., 2008). Children spend much of their day at school and physical education (PE) and recess programs at school could reduce the gap between actual and recommended physical activity (Wechsler et al., 2000). The availability and adequacy of facilities may be a critical component in the provision of school physical activity programs (Davison et al., 2006; Sallis, 2006).

This study documents the state of physical activity facilities in United States elementary schools and how it relates to child characteristics, school factors, PE, and recess. A number of studies suggest that neighborhood recreational facilities are associated with higher activity levels among youth and that facilities are often poorer or nonexistent in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Davison et al., 2006; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006; Ferreira et al., 2007; Powell et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2007; Romero, 2005; Sallis et al., 2000). Schools may counter or exacerbate this neighborhood effect. We are therefore interested in whether child and school disadvantage predicts lower quality facility provision, which in turn would be associated with less time scheduled for PE and recess programs. We also investigate if the relationship between facilities and physical activity programs is modified by environmental constraints such as a climate that is not supportive of outdoor activity, or a lack of alternate facilities, such as an auditorium or multipurpose room. Finally, we assess whether quality of facilities is associated with the obesity trajectory between kindergarten and 5th grade.

Data on the relationship between school facilities and physical activity are limited. Nationwide, it was reported that 22.6% of schools did not have a gymnasium (Lee et al., 2007). In a sample of elementary schools, facility availability and equipment were associated with more physical activity opportunities in a sample of elementary schools (Barnett et al., 2006). Facility provision alone may not be supportive of higher physical activity, of course, as this also depends on supervision and instruction (Sallis et al., 2001).

Methods

The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K)

The ECLS-K is conducted by the National Center for Educational Statistics. The base year cohort, selected based on a multistage probability design covering the United States is nationally representative of children attending kindergarten in the 1998–1999 school year. Responses are collected in each round of data collection from children, parents/guardians, teachers, school administrators, and school facility inspectors. Data from the spring of 1999 wave (corresponding to kindergarten) and the spring of 2004 (corresponding to 5th grade) were used for the analysis. Children from racial/ethnic minority groups or attending private schools were oversampled and about 50% of children who changed schools were randomly selected for follow-up. More details on the survey are available at http://nces.ed.gov/ecls/. Key measures are described below.

School facility measures

The school administrator (principal or headmaster) assessed the availability and adequacy of the school gymnasium, playground, multipurpose room, cafeteria, auditorium, and classroom. The gymnasium was considered to serve as the primary facility for PE while the playground was considered to be the primary facility for recess. The playground was defined as an alternate facility for PE while the gymnasium was an alternate facility for recess. For each facility the administrator was asked: “in general, how adequate is the [facility] for meeting the needs of the children in your school?” Response options included “Do not have,” “never adequate,” “often not adequate,” “sometimes not adequate,” and “always adequate.” As “do not have” and “always adequate” were the most common responses, the “never adequate,” “often not adequate,” and “sometimes not adequate” responses were collapsed into a category referred to as “inadequate” to preserve sample size. Two binary measures were constructed: (1) whether or not the school had the facility; and (2) whether or not the facility was adequate conditional on the school having the facility in question. The term “facility provision” refers to both facility availability and adequacy.

Physical education (PE) and recess time

The child's math and reading teachers reported the number of times PE and recess were held per week and the number of minutes per session. These numbers were multiplied by each other to obtain the minutes of PE and recess time in the past week. The average value was used if both teachers responded. Responses from teachers likely reflected scheduled times for PE and recess as opposed to the actual lengths of these programs.

Childhood obesity measures

Body-mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured height and weight. ECLS-K-trained assessors collected two measures each for height and weight using a Shorr Board (Shorr Productions, Olney, MD) and a digital bathroom scale. The age- and sex-specific BMI percentile for each child was calculated using a SAS program (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) based on the updated 2000 Growth Charts (Kuzmarski, 2002; CDC, 2000). Children with a BMI exceeding the 95th percentile were classified as obese and those with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles were classified as overweight. Obesity trajectory was defined as the change in BMI percentile over time.

School characteristics and other measures

The percentage of free-or-reduced lunch (FRPL) students at the school and whether or not the school received Title I funds were reported by the school administrator. Schools where 50% or more of the student body was minority were considered to be high minority while schools with at least 500 children enrolled were considered to be high enrollment. The child's parent or guardian reported on how safe it was for the child to play outside the home. This measure served as an indicator of the relative importance of having recreation facilities in the neighborhood. Household income and child race/ethnicity were reported by the parent and included as controls. School management type (private or public), census geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and degree of urbanization (regions which where large or mid-size cities were classified as urban, large or mid-sized suburbs, and large towns were classified as suburban and small towns and rural areas were classified as rural) were reported by the school administrator.

Climate zone

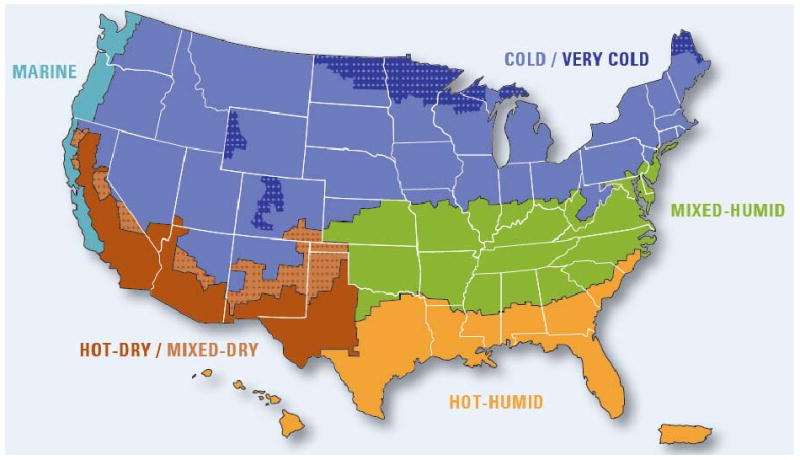

Each county in the United States is classified into one of six climate zones (refer to Fig. 1) as defined by a report commissioned to assist builders in home construction (U.S. Department of Energy Building America Program, 2007). Climate zones are defined by heating degree days (the difference between the average outdoor temperature and the room temperature), average temperatures, and precipitation. The “cold,” “very cold,” and “subarctic” zones were combined into the category “cold,” and the “hot-dry” and “mixed dry” zones were combined into the category “dry.”

Fig. 1.

Climate zones recognized by Building America. Reproduced with permission from: Building America Best Practices: Series for High-Performance Technologies: Determining Climate Regions, December 2007.

Climate data were merged with ECLS-K using the school county identifiers. The final analytic sample included 8392 fifth graders in 1387 schools across the country. Of these 6777children attended the same school in kindergarten and 5th grade and had recorded weight and height in both years.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and multivariate regression were used to analyze the correlates of facility provision, PE, recess, and obesity trajectory. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the statistical significance of differences in facility provision by child and school factors. Logistic models were estimated when facility provision was the dependent variable while linear models were estimated when PE or recess time was the dependent variable. Facility availability and adequacy were investigated separately. If facility provision was not determined to be a significant predictor for the full sample, the analyses were repeated for subgroups of schools with an environmental constraint. These constraints included urban location, having fewer than five alternate facilities, and climate zone. It is quite plausible that there are no overall effects and that facilities only matter in combination with other environmental constraints. For example, in a mild dry climate (like Southern California), outdoor PE is possible year round and there is much less need for an indoor facility. Similarly, multiple alternate facilities such as multipurpose rooms and cafeterias can substitute for designated gymnasiums. Child-level regressions were clustered on schools and employed robust standard errors to adjust for the sampling design of ECLS-K. Sampling weights were applied to approximate the 5th grade population. Regression results were not reported if the sample had fewer than 50 observations.

Results

Facility provision by child and school characteristics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the sample by facility provision. Of schools in the 5th grade sample 67.9% had a gymnasium and that figure was significantly lower for schools that were high enrollment, high minority, located in urban areas, or had fewer than five alternate facilities (P<0.05). Most schools in cold and mixed-humid zones had a gymnasium as compared with 24.3% in dry climate zones and 11.1% in marine climate zones. Hispanic and Black children were less likely to have a gymnasium at school than White children (49.1 and 76.1% as compared to 82.0%). Children from low-income households and for whom it was unsafe to play outside were also less likely to attend a school with a gymnasium. No significant findings emerged for obesity or overweight status (overweight status not shown).

Table 1.

Gymnasium and playground provision by child and school characteristics (ECLS-K).a

| Gymnasium available | Gymnasium adequateb | Playground adequatec | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | 95% CI | n | Mean | 95% CI | n | Mean | 95% CI | |

| Child level | |||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 4,983 | 82.0 | (81.0, 83.1) | 4,056 | 80.2 | (78.9, 81.4) | 4,899 | 66.1 | (64.8, 67.4) |

| Black | 897 | 76.1 | (73.3, 78.9) | 693 | 74.5 | (71.3, 77.8) | 845 | 54.8 | (51.4, 58.2) |

| Hispanic | 1,450 | 49.1 | (46.5, 51.7) | 710 | 80.1 | (77.1, 83.0) | 1,405 | 58.7 | (56.2, 61.3) |

| Otherd | 1,062 | 69.6 | (66.9, 72.4) | 619 | 67.1 | (63.4, 70.8) | 1,114 | 62.1 | (59.1, 65.1) |

| Household income (456 unknown)e | |||||||||

| $25,000 or less | 1,700 | 70.0 | (67.7, 72.1) | 1,146 | 76.0 | (73.5, 78.4) | 1,633 | 57.7 | (55.3, 60.1) |

| More than $25,000 | 6,236 | 76.0 | (74.9, 77.0) | 4,634 | 79.6 | (78.5, 80.8) | 6,101 | 64.5 | (63.3, 65.7) |

| Obesity statusf | |||||||||

| Not obese | 6,679 | 73.8 | (72.8, 74.9) | 4,823 | 78.1 | (77.0, 79.3) | 6,518 | 62.6 | (61.5, 63.8) |

| Obese | 1,713 | 74.1 | (72.0, 76.2) | 1,255 | 79.2 | (76.9, 81.4) | 1,658 | 63.1 | (60.8, 65.4) |

| Safety around home (628 unknown)g | |||||||||

| Not safe or somewhat safe | 1,799 | 67.2 | (65.1, 69.4) | 1,140 | 74.3 | (71.8, 76.8) | 1,720 | 56.0 | (53.6, 58.3) |

| Very safe | 5,965 | 77.2 | (76.2, 78.3) | 4,529 | 80.0 | (78.9, 81.2) | 5,848 | 65.3 | (64.0, 66.5) |

| Overall | 8,392 | 73.9 | (73.0, 74.8) | 6,078 | 78.3 | (77.3, 79.4) | 8,176 | 62.7 | (61.7, 63.8) |

| School level | |||||||||

| School enrollment | |||||||||

| <500 children | 776 | 75.5 | (72.5, 78.5) | 586 | 76.6 | (73.2, 80.1) | 758 | 60.4 | (56.9, 63.9) |

| >500 children | 611 | 58.3 | (54.3, 62.2) | 356 | 79.8 | (75.6, 84.0) | 595 | 61.3 | (57.4, 65.3) |

| Minority | |||||||||

| <50% | 789 | 78.1 | (75.2, 81.0) | 616 | 79.1 | (75.8, 82.3) | 779 | 65.6 | (62.3, 68.9) |

| >50% | 598 | 54.5 | (50.5, 58.5) | 326 | 75.4 | (70.8, 80.2) | 574 | 54.4 | (50.3, 58.4) |

| Number of facility alternatesh | |||||||||

| Less than five | 1,161 | 65.9 | (63.2, 68.6) | 765 | 77.6 | (74.7, 80.6) | 1,176 | 59.7 | (56.9, 62.5) |

| Has five | 226 | 78.3 | (72.9, 83.7) | 177 | 78.5 | (72.4, 84.6) | 177 | 68.3 | (61.4, 75.3) |

| Degree of urbanizationi | |||||||||

| Urban | 646 | 60.4 | (56.6, 64.2) | 390 | 78.7 | (74.6, 82.8) | 625 | 59.2 | (55.3, 63.1) |

| Suburban | 525 | 70.5 | (66.6, 74.4) | 370 | 78.6 | (74.5, 82.8) | 518 | 62.7 | (58.6, 66.9) |

| Rural | 216 | 84.3 | (79.4, 89.2) | 182 | 74.2 | (67.8, 80.6) | 210 | 61.0 | (54.3, 67.6) |

| Climate zone (29 unknown)j | |||||||||

| Cold | 515 | 88.3 | (85.6, 91.1) | 455 | 77.4 | (73.5, 81.2) | 500 | 61.0 | (56.7, 65.3) |

| Dry | 255 | 24.3 | (19.0, 29.6) | 62 | 66.1 | (54.0, 78.2) | 252 | 54.4 | (48.2, 60.6) |

| Hot-humid | 210 | 45.7 | (38.9, 52.5) | 96 | 84.4 | (77.0, 91.8) | 206 | 66.0 | (59.5, 72.5) |

| Marine | 36 | 11.1 | (0.3, 21.9) | 4 | – | – | 36 | – | – |

| Mixed-humid | 342 | 90.4 | (87.4, 93.5) | 309 | 79.3 | (74.7, 83.8) | 331 | 61.3 | (56.1, 66.6) |

| Overall | 1,387 | 67.9 | (65.5, 70.4) | 942 | 77.8 | (75.2, 80.5) | 1,353 | 60.8 | (58.2, 63.4) |

All analyses are univariate. Values at the child level are weighted; values at the school level are not weighted.

Conditional on the school having a gymnasium.

Conditional on the school having a playground.

Includes Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Alaskan Natives, and multirace non-Hispanics.

Reported by the child's parent or guardian.

A child is obese if the BMI exceeds the 95th age- and sex-specific BMI percentile.

Reported by the child's parent or guardian.

Facilities that could serve as a substitute for a gymnasium or playground include multi-purpose rooms, cafeterias, classrooms, and auditoriums. A playground was counted as a substitute for a gymnasium and a gymnasium was counted as a substitute for a playground.

Rural refers to small towns, suburban refers to large and mid-size suburbs, and large towns and urban refers to large and mid-size cities.

Refer to Fig. 1 for definition.

The gymnasium was reported to be adequate in 77.8% of schools. Differences by child and school characteristics were similar but less stark as compared with our findings regarding gymnasium availability. For example, high enrollment, high minority, and urban schools were not more likely to have an inadequate gymnasium.

As only 2.5% of schools do not have a playground, only the correlates of having an adequate as compared to an inadequate playground are displayed in Table 1. Schools with a high fraction of minority children were more likely to report an inadequate playground. Children from low-income households or from racial/ethnic minorities were also less likely to have an adequate playground at school.

Physical education and recess time by facility provision

Schools provided an average of 77 min for PE class and 38 min for recess during the past week. Table 2 shows that schools with a gymnasium provided 8.3 min more of PE per week than schools without a gymnasium after controlling for other covariates (P<0.01). The association is stronger for schools in humid climate zones—gymnasium availability in hot-humid regions was associated with an additional 17.4 min of PE while it was associated with an additional 25.0 min of PE in mixed-humid regions. Gymnasium adequacy was not associated with significantly more PE time, nor was playground adequacy associated with more recess time.

Table 2.

Association between facility provision and minutes of physical education and recess time per week.a

| Physical education time (min) |

Recess time (min) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | (SE) | Coeff | (SE) | Coeff | (SE) | |

| Facility provision | ||||||

| Gymnasium available | 8.29 | (3.79)** | ||||

| Gymnasium available and adequate | 3.04 | (3.05) | ||||

| Playground available and adequate | -1.41 | (1.85) | ||||

| Number of alternates | -1.00 | (1.41) | 1.9 | (1.53) | -1.05 | (1.01) |

| Climate zone (Ref=cold)b | ||||||

| Dry | 36.50 | (5.95)*** | 45.32 | (8.59)*** | -1.46 | (2.92) |

| Hot-humid | 27.29 | (5.98)*** | 44.10 | (5.72)*** | -21.43 | (2.40)*** |

| Marine | 9.16 | (7.50) | 22.65 | (25.53) | 2.13 | (5.76) |

| Mixed-humid | 30.57 | (10.19)** | 5.58 | (2.74) * | -12.45 | (2.20)*** |

| Interactions between facility provision and climate zonec | ||||||

| Dry*gym available | 8.92 | (9.97) | – | – | – | – |

| Hot-humid*gym available | 17.40 | (8.25)* | – | – | – | – |

| Marine*gym available | 14.22 | (25.55) | – | – | – | – |

| Mixed-humid *gym available | 24.96 | (10.53)* | – | – | – | – |

| School characteristics | ||||||

| High enrollmentd | 1.22 | (2.81) | 1.74 | (2.82) | -4.37 | (1.84) * |

| Private | -2.24 | (3.19) | 2.39 | (3.52) | 0.06 | (3.27) |

| Title 1 receipt | -0.72 | (2.47) | -6.10 | (2.67) | -0.18 | (2.16) |

| High minority e | -6.28 | (2.80)** | -4.35 | (3.02) | -1.72 | (2.35) |

| Urbanization (Ref=urban)f | ||||||

| Suburban | -2.19 | (2.89) | -1.92 | (3.36) | 1.41 | (2.09) |

| Rural | 2.94 | (3.45) | 5.39 | (3.49) | 11.05 | (3.10)*** |

| Constant | 62.87 | (6.57)*** | 62.03 | (6.92)*** | 57.00 | (5.04)*** |

| Schools, n | 1,358 | 926 | 1,325 | |||

* P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001.

Refer to Fig. 1 for definition.

Interactions for models where gymnasium adequacy and playground adequacy served as the dependent variables were not included because the main effects were not statistically significant.

School has 500 or more students.

School has 50% or higher minority students.

Rural refers to small towns, suburban refers to large and mid-size suburbs, and large towns and urban refers to large and mid-size cities.

Schools located in dry or hot-humid zones spent 25 min more on average in PE in the past week as compared with schools in cold zones. Schools that were high minority also reported 6.3 fewer minutes of PE class (P<0.05). Schools in rural regions reported 11.1 min more of recess as compared to urban regions while no differences by urbanization were found for PE (P<0.001). Schools that were high enrollment also devoted less time to recess. The number of alternate facilities was not associated with PE or recess time.

Only the coefficient of gymnasium availability was significant for the full sample, but not the coefficients for administrator-reported gymnasium or playground adequacy. This could be because many schools were not constrained and we therefore repeated the analysis for schools with an environmental constraint. Environmental constraints included urban location, less than five alternate facilities, and climate zone. Table 3 presents these results. Gymnasium adequacy was associated with more PE time in all of the considered subgroups, but none of them were statistically significant except for schools in an urban location. For these schools, gymnasium availability was associated with 10.3 min more of PE time (P<0.05). Playground adequacy was not associated with more recess time for several subgroups such as schools located in dry or hot-humid climate zones.

Table 3.

Association of facility adequacy with physical education and recess time for schools with an environmental constraint.a,b,c

| PE time (min) | Recess time (min) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gymnasium adequacyd | Playground adequacye | |||||

| n | Coeff | (SE) | n | Coeff | (SE) | |

| Urban | 382 | 10.32 | (5.15) * | 611 | 2.81 | (2.58) |

| <5 alternates | 750 | 4.87 | (3.41) | 1,149 | -1.97 | (2.01) |

| Climate zone | ||||||

| Cold | 455 | 2.43 | (3.29) | 500 | -5.34 | (3.37) |

| Dry | 62 | 2.65 | (20.65) | 252 | 5.54 | (4.29) |

| Hot-humid | 96 | 7.84 | (16.90) | 206 | -2.67 | (3.39) |

| Marine | 4 | – | – | 36 | – | – |

| Mixed-humid | 309 | 1.67 | (4.95) | 331 | 1.93 | (3.33) |

* P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001.

Other controls include enrollment, public, Title 1 funds receipt, % minority, census region, degree of urbanization, and number of alternate facilities.

Environmental constraints at school may include urban location, having fewer than 5 alternate facilities, and climate zone location.

Conditional on the school having a gymnasium.

Conditional on the school having a playground.

Obesity trajectory by facility provision

The prevalence of obesity in the sample increased from 11.8 to 20.1% between kindergarten and 5th grade and the average BMI percentile increase was 5.4 units. Gymnasium and playground provision in 5th grade were not predictive of a lower obesity or overweight trajectory both overall and for stratifications separately by gender, obesity, or overweight status in kindergarten, household poverty, region, and climate zone (results not shown). Findings did not change substantially or gain statistical significance when facility provision in kindergarten was included as a control in our models.

Discussion

We find that 26.1% of children attended a school without a gymnasium which is comparable to figures reported elsewhere (Lee et al., 2007). When there was a gymnasium, it was rated as inadequate by the administrator in one-fifth of the schools. Most children were in schools with a playground, but overall 37.3% of students had an inadequate playground at school. Low socioeconomic status children, including those from racial/ethnic minorities and low-income households, were less likely to attend a school with a gymnasium. While school facilities may represent a safe area to play for children in neighborhoods with safety concerns, we find that these children were more likely to attend schools with worse facility provision. These findings complement other studies indicating that neighborhoods with low-income and high-minority residents have less access to recreational facilities (Powell et al., 2006; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006).

Gymnasium availability was associated with 8.3 min more of PE time per week for all schools in the sample. For schools in mixed-humid or hot-humid climate zones, however, the effect was three times as large. These figures represent 10.8 and 32.5% of the average time all children in the sample spend in PE. The sample averages of 77 min of PE and 38 min of recess per week fall short of the recommended levels of 150 min and 100 min, respectively (IOM, 2005; NASPE, 2006).

The stronger association between gymnasium availability and PE time for schools in hot-humid and mixed-humid climate zones may be due to the survey being conducted in April. Although we are unable to test this hypothesis with these data, we would expect that the association would be stronger for schools in cold climates during the winter months. That schools in hot-humid and mixed-humid zones spend more time in PE and less in recess also supports weather being a determining factor in school physical activity programs.

While gymnasium and playground adequacy were not found to be related to PE and recess time for the overall sample, gymnasium adequacy was found to be associated with PE time for schools in urban locations. As space is at a higher premium for urban schools, adequacy may refer to the capacity of the facility in relation to class sizes. Statistically significant findings were not obtained for other environmental constraints as we had hypothesized.

Facility provision is not a significant predictor of obesity trajectory, although we found gymnasium provision to be associated with more PE time. But the amount of extra PE would be a very small part of overall energy expenditure even if children were active, so seeing a significant association would have been unusual. Our measure of PE time is more likely to be scheduled as opposed to actual time, let alone active time. Facilities may shape the curriculum and quality of PE class, but no information regarding how time is spent is collected in the survey. Our analysis also does not consider factors such as dietary intake that may also be implicit in obesity trajectory.

Important Study Limitations

School administrators were asked about physical activity programs in the previous week, not over the course of a year, and their responses were collected in the spring. Our measures of facility provision were reported by the school administrator and not validated by an outside source. School administrators may have demonstrated a reluctance to report that facilities were inadequate or may have exaggerated their inadequacy in order to procure more funds for renovations. The latter bias may explain our findings that lower SES schools have worse facility provision. No information regarding the brand and model of the scales used to measure child weight was included in the ECLS-K documentation. This limited our ability to investigate if calibration may have affected the validity of the measurements taken. Lastly, we are unable to determine if the schools provided after-school programs or had established community partnerships even though studies suggest that these might be important policies for increasing children's engagement in physical activity (CDC, 2008; Mota et al., 2003; Trost et al., 2008). After-school or weekend access to school gymnasiums and playgrounds may be particularly important for children from neighborhoods that lack green space or recreational facilities.

Conclusions

We found differences in facility provision by sociodemographic characteristics and that gymnasium availability was associated with more PE time particularly for schools in mixed- and hot-humid climate zones. Insights into how school facilities shape physical activity programs and child physical activity levels could support the development of appropriate recommendations and interventions.

Acknowledgments

Meenakshi Fernandes performed the statistical analysis for the manuscript. Dr. Roland Sturm and Meenakshi Fernandes wrote the manuscript. Financial support was provided by RWJ Grant 61126 and NICHD Grant R01HD057193. The authors acknowledge Gail Mulligan and Jill Carlivati at the National Center for Education Statistics, Larry Picus, Professor of Education at the University of Southern California, and Bill Fowler, Associate Professor of Education at George Mason University, for their kind assistance regarding the facility measures in the ECLS-K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnett TA, O'Loughlin J, et al. Opportunities for student physical activity in elementary schools: a cross-sectional survey of frequency and correlates. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(2):215–232. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for physically active americans. [8/20/09];2008 Available at http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Growth chart SAS program. 2000 Downloaded May 21, 2008 from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm.

- Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children's physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira IK, van der Horst, et al. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth—a review and update. Obes Rev. 2007;8(2):129–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen PM, Nelson C, et al. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing childhood obesity: health in the balance. National Academy Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. Vital Health Stat. 246. Vol. 11. 2002. CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development; pp. 1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Burgeson CR, et al. Physical education and physical activity: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J School Health. 2007;77(8):435–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota J, Santos P, et al. Patterns of daily physical activity during school days in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15(4):547–53. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) Reston, VA: 2006. Recess for elementary school students. Available online at: http://www.aahperd.org/naspe/pdf_files/pos_papers/RecessforElementarySchoolStudents.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ, et al. The availability of local-area commercial physical activity-related facilities and physical activity among adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4 Suppl):S292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Harper D. Availability of physical activity-related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1676–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ. Low-income neighborhood barriers and resources for adolescents' physical activity. J Adol Health. 2005;36:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Conway TL, et al. The association of school environments with youth physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):618–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. The role of built environments in physical activity, eating, and obesity in childhood. Future Child. 2006;16(1):89–108. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, et al. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–75. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, et al. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):622–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy Building America Program. Building America best practices: series for high-performance technologies: determining climate regions. 2007 December; Prepared by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory & Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Available at: http://apps1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/publications/pdfs/building_america/climate_region_guide.pdf. Last downloaded 2/10/09.

- Wechsler H, Devereaux RS, et al. Using the school environment to promote physical activity and healthy eating. Prev Med. 2000;31(2):121–137. [Google Scholar]