Abstract

Allergic diseases, which have reached epidemic proportions, are driven by inappropriate immune responses to a relatively small number of environmental proteins. The molecular basis for the propensity of specific proteins to drive maladaptive, allergic responses has been difficult to define. Recent data suggest that the ability of such proteins to drive allergic responses in susceptible hosts is a function of their ability to interact with diverse pathways of innate immune recognition and activation at mucosal surfaces. This review highlights recent insights into innate immune activation by allergens—via proteolytic activity, engagement of pattern recognition receptors, molecular mimicry of TLR signaling complex molecules, lipid binding activity, and oxidant potential—and the role of such activation in inducing allergic disease. A greater understanding of the fundamental origins of allergenicity should help define new preventive and therapeutic targets in allergic disease.

Introduction

The prevalence of allergic diseases has increased dramatically over the last few decades, with population prevalence rates reaching 30% in the industrialized nations that have led the epidemic. The defining feature of allergic disorders is their association with aberrant levels, and targets, of immunoglobulin E (IgE) production. Allergy is thought to result from maladaptive immune responses to ubiquitous, otherwise innocuous environmental proteins, referred to as allergens1. Allergens, by definition, are proteins that have the ability to elicit powerful T helper lymphocyte type 2 (Th2) responses, culminating in IgE antibody production (atopy). While allergens represent a minute fraction of the protein universe that humans are routinely exposed to, allergenicity is a very public phenomenon, with the identical proteins behaving as allergens in different allergic patients. Why specific proteins drive such aberrant T cell and B cell responses is a basic mechanistic question that has remained largely unanswered.

Allergens derive from a variety of environmental sources such as plants (trees, grasses), fungi (Alternaria alternata), arthropods (mites, cockroaches), and other mammals (cats, dogs, cows). Allergens constitute a diverse range of molecules, varying in size from small to large multi-domain proteins. As they are derived from complex living organisms they serve a broad range of functions in their respective hosts, from structural to enzymatic. For example, the common house dust mite allergens include several cysteine proteases (Der p 1, Der p 3), serine proteases (Der p 3, Der p 6, Der p 9), chitinases (Der p 15, Der p 18), lipid-binding molecules (Der p 2), and structural molecules such as tropomyosin (Der p 10). Some are species specific; others are molecules with broad biochemical homology that are found in many species. Much work has centered on the study of the allergen epitopes recognized by T and B cells. However, as there is no compelling evidence for common structural characteristics among the diverse T and B cell epitopes recognized in allergic responses 2,3,4, it appears doubtful that the presence of such B cell and T cell epitopes are sufficient to endow a protein with allergenic potential. Other factors such as the size, glycosylation status, resistance to proteolysis, and enzymatic activity, have been suggested to play an important role in allergenicity. However, none of these factors have been consistently linked with allergenic potential. For example, glycosylation appears not to be a common critical determinant of allergenicity as both glycosylated and non-glycosylated proteins act as food allergens. It may be that there are many structural paths to allergenicity, but the absence of any common structural motif or conformational sequence pattern leaves open the possibility that proteins with allergic potential exhibit a necessary commonality of biological function. Indeed, it has recently been proposed that allergens are linked by their ability to activate the innate immune system of mucosal surfaces, triggering an initial influx of innate immune cells that subsequently drive Th2-polarized adaptive immune responses. It should be noted that, reductive experimental systems aside, natural exposure is not to single, purified proteins, but to complex mixtures of molecules. It may well be that the innate immune-activating molecules are not identical to the proteins recognized by allergic responses, although this would still beg the question as to why those particular proteins are so recognized among the many present during exposure. In this review, we will address recent advances in our understanding of the diverse innate immune-activating properties of allergens that appear to endow them with a propensity for driving Th2 immune responses.

Protease Activity and Allergic Sensitization

Several allergens have cysteine or serine protease activity, including diverse allergens from arthopods [e.g., house dust mites 5-7, German cockroaches 8, fungi (Alternaria alternata)9 and Cladosporium herbarum 10, mammals (e.g., Felis domesticus)11, plants (e.g. pollens from ragweed 12]. In addition, many forms of occupational allergy are associated with encounters with proteolytic enzymes such as those used in the manufacture of detergents (alkaline detergents)13, or in the food industry (papain)14.

Several lines of evidence suggest that proteases may facilitate allergen sensitization. First, intrinsic protease activity appears to be linked with sensitization ability in several allergens. Removal of proteases from A. fumigatus 15, German cockroach frass 16, American cockroach Per a 10 antigen17, Epi p1 antigen from the fungus Epicoccum purpurascens 18 or Cur 11 antigen from the mold Curvularia Iunata 19 was reported to decrease airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mouse models of allergic asthma. Secondly, direct exposure of mice to proteolytic enzymes such as papain can induce allergic sensitization 20. Moreover, co-administration of active proteases from A. fumigatus with the tolerogenic antigen, ovalbumin (OVA), resulted in allergic sensitization 15. As co-exposure to a tolergenic protein with a protease can induce allergic sensitization, proteases found in ambient air derived from bacterial and viral species may play accessory roles. Lastly, subcutaneous injection of a serine protease inhibitor, nafamostat mesilate, during sensitization to house dust mite extracts blunted the development of allergic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness 21.

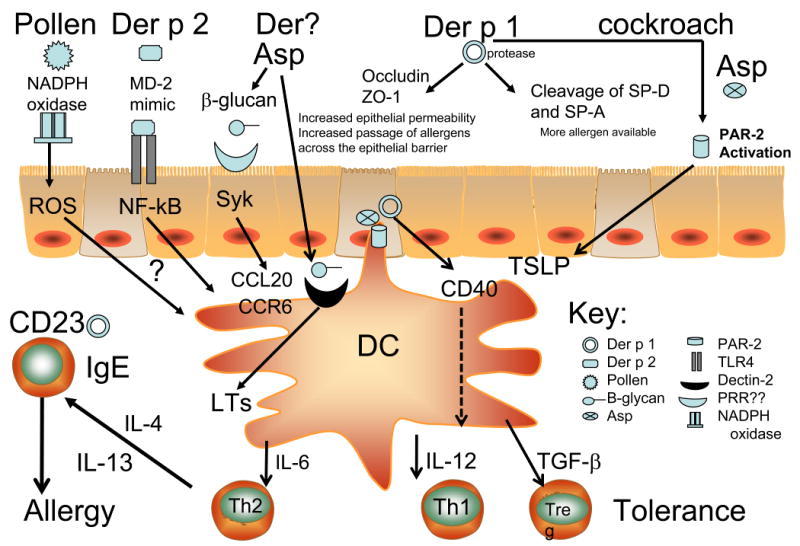

The exact mechanisms by which proteases can drive allergic sensitization are not well understood. Several mechanisms have been postulated. Firstly, protease activity may increase transepithelial access of allergens to critical cells of the innate immune response, such as dendritic cells (DCs). For example, the cysteine protease Der p 1, can alter epithelial permeability through disruption of epithelial tight junctions and a reduction in ZO-1 and occludin content 6. Consistent with this, proteolytic enzymes from a number of tree and grass pollens have also been shown to degrade ZO-1 and disrupt tight junctions 22. Moreover, Der p 1 has been shown to cleave α-1-anti-trypsin, inhibiting its ability to protect the respiratory tract against serine proteases such as Der p 3 and Der p 9. This may disrupt the protease-anti-protease balance in mucosal tissues, enhancing the activity of both endogenous and exogenous proteases and leading to enhanced tissue damage and immune activation.

Secondly, the cysteine protease activity of several mite allergens (Der p 1, Der f 1) may directly impair innate defense mechanisms in the lung by degrading and inactivating lung surfactant proteins (SP) −A and −D 23. SP-A and AP-D are calcium-dependent carbohydrate-binding proteins with multiple innate immune functions, including bacterial agglutination and modulation of leukocyte functions. Importantly, SP-D and SP-A have been shown to protect against Aspergillus fumigatus-induced allergic inflammation in mice 24, 25, likely via binding to glucan moieties of inhaled allergens and facilitation of their clearance.

Proteases may have more direct immunomodulatory actions as well. Proteases from mites, cockroaches, and fungi can increase the expression of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8 and GM-CSF 5, 6, 8, 9, which may lead to the recruitment, activation and/or enhanced survival of DCs at the mucosal surface. Additionally, Der p 1 has been shown to influence the expression of costimulatory molecules such as CD40 on DCs. Der p 1 can cleave CD40 on human monocyte-derived DCs, resulting in inhibition of the production of the pivotal Th1-differentiating cytokine, IL-12 26. The suppression of CD40 signaling and IL-12 production may induce a shift towards Th2 responses. A similar effect has been observed with the mold Aspergillus (Asp). Exposure of healthy human monocyte-derived DCs to Asp induced their maturation and enhanced their ability to prime Th2 immune responses in allogeneic naïve T cells as compared with naive T cells primed with LPS-activated DCs 27. When the proteolytic activity of Asp was neutralized by chemical inactivation, Asp failed to up-regulate costimulatory molecules on DCs, and these DCs did not prime a Th2 response in naive T cells. The skewed Th2 response was thought to occur as a result of suppressed IL-12 production by Asp-primed DCs. Interestingly, although the exact mechanisms by which allergen-derived proteases influence the decision making capability of DCs are not well understood, recent studies suggest that protease containing allergens such as Der p 1 can target two C-type lectins, DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR 28. Loss of DC-SIGN expression following Der p 1 treatment led to a reduction in its binding to its ligand, ICAM-3, on naïve T cells, which is thought to be important in Th1 signaling 28. Thus the combined proteolytic activities of Der p 1 on surface expression of molecules such as CD40, and DC-SIGN could have profound effects on the decision making capability of DCs, biasing adaptive immunes response towards a Th2 pattern of response.

Recently, study of the occupational allergen, papain (commonly used in the food industry), has led to the novel hypothesis that proteases can directly prime Th2 immune responses through actions on basophils 20. Data suggest that papain can cleave a yet-to-be identified host sensor which, in turn, activates basophils to produce IL-4, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)—driving Th2 differentiation. This intriguing work supports the concept that host detection of protease activity associated with allergens may provide a unique pathway of innate immune activation. The generality of this pathway, as well as its molecular identification, remain to be defined.

Allergen-derived proteases can have direct effects on adaptive immune responses as well, through cleavage of molecules such as CD25, and CD23. Specifically, Der p 1 has been shown to be able to cleave the α chain of the IL-2 receptor (CD25) on human T cells 29 (Figure 1). As a result, T cells exposed directly to Der p 1 display markedly reduced Th1 cytokine production and enhanced Th2 cytokine production, something dependent on the protease activity or Der p 1. Cleavage of CD25 might also, of course, alter regulatory function, as IL-2 stimulation is required for the maintenance of regulatory T cells in the periphery. The overall effect may be to shift the balance of immune responses from a tolerogenic response to one favoring a Th2 pattern of response. Allergenic proteases such as Der p 1 have also been shown to be able to cleave the low affinity receptor for IgE, CD23, from the surface of human B cells, releasing the soluble form of the receptor 30 (Figure 1). As the membrane-bound form of the IgE receptor is thought to act as a negative regulator of IgE synthesis, Der p 1 cleavage of CD23 could potentially disrupt the negative feedback signal and enhance IgE synthesis, thereby amplifying the allergic response. Anti-trypsin can inhibit this effect of Der p 1 on CD23 cleavage, suggesting that disruption of the balance between proteases and protease inhibitors might play a role in allergic sensitization. It should be noted that whether intact proteases such as Der p 1 actually gain functional access to lymphocytes in vivo remains an open question.

Figure 1. Schematic of innate immune mechanisms activated by allergens.

The biological effects of some allergenic proteases may also be mediated through activation of the Protease-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR2). PARs (1,2,3,4) are a family of proteolytically activated G-protein coupled receptors. Proteases cleave within the N-terminus of the receptors and expose a tethered ligand domain that binds and activates the cleaved receptor. Several lines of evidence suggest that PAR2, in particular, may be important in allergic sensitization. It is expressed by many cells in the lung, including airway epithelial cells 31, fibroblasts 32, macrophages 33 and mast cells 34, and, importantly, patients with asthma have been shown to exhibit increased expression of PAR2 on respiratory epithelial cells 35. Several house dust mite allergens (Der p1, (30), Der p 3, Der p 9), along with German cockroach extract 36, have been shown to be able to cleave and activate PAR2 (Figure 1). Several reports have shown that activation of PAR2 by house dust mite extract 7, German cockroach 37, or the mold allergen Pen c 13 38 leads to increased cytokine production by airway epithelia. Specifically, airway epithelial cells were shown to increase the expression of TSLP through the activation of PAR2 when treated with papain, trypsin or the fungus Alterneria 9. As TSLP drives DC polarization of naïve T cells to a Th2 phenotype, these results suggest that PAR2 activation may serve as a link between innate and adaptive immune responses.

Several mouse models of allergic inflammation have also underscored a potential role for PAR2 in allergic sensitization. For example, one recent study showed that tolerance to inhaled OVA could be overcome by co-administration of PAR2-activating peptides to the airways, promoting allergic sensitization 39. Other studies have shown that overexpression of PAR2 in mice renders them susceptible to allergic airway inflammation when sensitized and challenged locally with OVA, as compared to wildtype controls 40. In contrast, PAR2 deficient mice were protected against allergic inflammation. While these data strongly support the concept that protease activity may lead to airway allergic sensitization via PAR2 activation, there are a few reports suggesting that PAR2 activation may also reduce airway inflammation. For example, despite the fact that TLR4 (vide infra) and PAR2 signaling have been shown to exhibit cooperativity 41, PAR2-activating peptides have been reported to inhibit lipopolysaccharide(LPS)-induced neutrophil influx into mouse airways 42. In a rabbit model of experimental asthma, sensitization to the pollen Parietaria judaica, followed by allergen challenge in the presence or absence of a PAR2-activating peptide, led to PAR2-mediated attenuation of the development of airway hyperresponsiveness and airway eosinophilia 43. It is possible that the discrepancies in these results are due to the timing of PAR2 activation, with activation by exogenous proteases during generation of immune responses having different effects than that occurring in the midst of an ongoing inflammatory response.

Toll-like Receptors, Lipid-Binding Activity and Allergic Sensitization

Recent recognition of the critical roles played by innate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), in activation and instruction of antigen-presenting cells (APCs)44 has led to the exploration of the role of these pathways in allergic responses. It will be noted that, while TLR-driven activation of Th1 responses by DCs is well-studied and -understood, the receptors and pathways driving Th2 immune responses have been considerably less tractable to experimental investigation.

Numerous studies have probed the role of TLR4 signaling in allergic inflammation. Epidemiological studies have reported an inverse correlation between high levels of bacterial products such as LPS in the ambient environment during very early life and the subsequent development of atopy and allergic disease 45-47. It has been postulated, pace the hygiene hypothesis, that such exposures drive robust counter-regulatory tone in the developing immune system 48. LPS exposure can also exacerbate established asthma, however, probably by direct stimulation of airway pro-inflammatory responses 49. Experimental mouse models have provided mechanistic insight into the ability of LPS exposure to regulate the development of allergic asthma. As predicted by the hygiene hypothesis, LPS dose appears to be a critical variable. While airway sensitization with OVA along with “very low dose” (<1 ng) LPS was reported to induce tolerance, sensitization in the presence of “low dose” (100 ng) LPS drove TLR-dependent, Th2 inflammation, and sensitization in the presence of “high dose” (100 ug) LPS led to a Th1 (and likely a regulatory) response 50, 51. Recent studies using bone marrow chimeras indicate that TLR4 signaling in radioresistant cells, not radiosensitive hematopoietic cells, are necessary and sufficient for DC activation and priming of allergic effector T helper responses in the lung in response to dust mite extracts 52. As for other TLRs, TLR2 ligands have been shown to be able to drive 53 or inhibit 54 Th2 differentiation and allergic inflammation in the lung.

A recent study reported a more direct link between TLR signaling and allergic sensitization. Among defined dust mite antigens, Der p 2 and Der f 2 have the highest rates of skin test positivity in atopic patients 55. Notably, sequence homology places these allergens in the MD-2-related lipid-recognition (ML) domain family of proteins 56,57—MD-2 being a secreted protein that is the LPS-binding member of TLR4 signaling complex. As the crystal structures of Der p 2 and MD-2 exhibit structural homology, Trompette et al. 58 examined whether Der p 2 exhibited functional homology as well. Indeed, they reported that Der p 2 can facilitate TLR4 signaling through direct interactions with the TLR4 complex, reconstituting LPS-driven TLR4 signaling in the absence of MD-2 and facilitating such signaling in the presence of MD-2 (Figure 1). They further found that Der p 2 could facilitate LPS signaling in primary APCs, with or without MD-2 being present. Finally, they reported that the in vitro functional and biochemical activity of Der p 2 mirrors its in vivo allergenicity—Der p 2 drives experimental allergic asthma in a TLR4-dependent manner, retaining this property in mice with a genetic deletion of MD-2. These data suggest that Der p 2's propensity to be targeted by the adaptive immune response is a function of its autoadjuvant properties. In this light, it should be noted that efficient generation of effector T cell responses has been shown to depend on the presence of TLR ligands in the specific DC phagosome that contains the antigen 59. In the case of Der p 2, antigen and TLR ligand are, perforce, co-localized. These data also suggest the possibility that Der p 2-mediated facilitation of TLR4 signaling under conditions of bacterial product exposure— those associated with increasing rates of aeroallergy in the urban, Westernized world— may shift the LPS-response curve from the tolerizing into the Th2-inducing range. Der p 2 may also promote exacerbation of established asthma by facilitating TLR4 signaling by airway epithelial cells— cells reported to express TLR4, but little or no MD-2, in the basal state 60.

Several other members of the MD-2-like lipid-binding family are major allergens4, suggesting generality for these findings. More broadly, however, greater than 50% of defined major allergens are thought to be lipid-binding proteins 4, something that suggests that intrinsic adjuvant activity by such proteins and their lipid cargo is likely to have wide generality as a mechanism underlying the phenomenon of allergenicity. Further studies defining the lipids normally bound by these allergens, the receptors thereby activated, and the pathways of innate and adaptive immune response driven by such activation are awaited. It should be noted that, in addition to activation of TLRs, lipid ligands are known to be important drivers (and targets) of innate lymphocyte responses.

Carbohydrate Structures and Allergic Sensitization

Recent data also suggest an important role for complex carbohydrates in driving Th2 immune responses. Helminth-derived carbohydrates such as lacto-N-fucopentaose III (LNFPIII) have been shown to promote Th2 responses via their ability to activate DCs in vivo 61. In addition, LNFPIII has been shown to be able to promote Th2 responses to a co-administered, unrelated antigen such as human serum albumin 62. Though the mechanisms underlying DC activation by LNFPIII glycoconjugates has not been fully elucidated, it involves ligation of C-type lectins on the DC, leading to subsequent antagonism of TLR signaling. Support for a broad role for complex carbohydrates, in particular glucans, in allergen-associated Th2 immune responses is emerging. Glucans are a diverse class of naturally occurring glucose polymers, which can be short or long, branched or unbranched, exist as α or β isomers, and be soluble or particulate. For the purposes of this discussion, we are mostly concerned with the β-glucans, which contain a polyglucose, (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan, and are commonly found in the cell walls of fungi, pollens, and certain bacteria. In plants, polymers of β-glucans are thought to protect the developing pollen during meiosis, and are later destroyed by the enzyme (1→3)-β-d-glucanase to liberate the microspores. Although β-glucans are widely expressed, they are not found in mammalian cells. As such, they can act as PAMPs, triggering immune responses through activation of specific PRRs.

The immunostimulatory properties of β-glucans have been recognized for decades, since their identification as the immunoactive component of mushrooms 63. More recently, β-glucans have been shown to be able to drive Th2 responses. For example, it has been reported that β-glucan structures present in the peanut glycoallergen Ara h 1 have Th2 inducing characteristics 64 native, but not deglycosylated, Ara h 1 was shown to activate human monocyte-derived DC and induce IL-4 and IL-13 secreting Th2 cells.

Exposure to β-glucans has also been shown to induce airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic humans 65. Studies in guinea pigs have shown that direct delivery of (1—3)-β-D-glucan to the airways can induce the recruitment of lung eosinophils and lymphocytes 66. In mice, exposure to soluble β-glucan isolated from Candida albicans 67 markedly exacerbated OVA-induced eosinophilic airway inflammation, concomitant with enhanced lung expression of Th2 cytokines and IL-17A. Exposure to β-glucans plus OVA increased the number of cells bearing MHC class II and the expression of APC-related molecules such as CD80, CD86, and DEC205 on bone marrow derived DCs. In support of a role of β-glucans in the recruitment and activation of DCs at mucosal surfaces, recent studies have shown that β-glucans contained in house dust mite extracts and in moulds may initiate immune responses at the mucosal surface. House dust mite extract-mediated induction of the release of the chemokine, CCL20, which recruits immature DCs, by human airway epithelial cells in culture, was shown to occur through β-glucan and Syk-dependent signaling pathways 68 (Figure 1). Although the exact lectin receptor mediating these effects was not identified in these studies, the results suggested that β-glucan moieties contained in house dust mite extracts might mediate early processes leading to immature DC recruitment to the airways. This concept is supported by another recent study that showed that dectin-2 receptor signaling pathways (Dectin-2/FcRgamma/Syk) mediated the production of cysteinyl leukotrienes in bone marrow-derived DCs following stimulation with house dust mite extracts or Aspergillus 69 (Figure 1). Taken together, these findings identify the dectin-2/FcRgamma/Syk axis as a novel receptor mediated pathway by which several potent allergens are recognized by innate immune cells at the airway surface, linking them with the development of Th2-skewed adaptive immune responses.

Consistent with a role for lectins in driving Th2 immune responses, blockade of the mannose receptor, an endocytic C-type lectin receptor, significantly reduced Der p 1 uptake by DCs 70. These findings are consistent with previous findings suggesting that engagement of the mannose receptor by selected ligands on human DCs leads to the induction of a DC phenotype favoring Th2 polarization 71. Although the study of the role of glucans as Th2-inducing PAMPs is only in its infancy, data to date suggest that carbohydrate moieties contained in common allergens act as strong Th2 inducers via activation of variety of C-type lectin receptors on DCs.

Oxidative activity and Allergen Sensitization

It has recently been shown that common allergenic pollen grains contain nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) [NAD(P)H] oxidase activity as well as allergens 72. Such pollen grains have been shown to significantly increase the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cultured cells, and to be able induce allergic airway inflammation in experimental animals 73 (Figure 1). Pretreatment of these pollen grains with NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitors attenuated their capacity to increase ROS levels in airway epithelial cells and subsequent airway inflammation. Similarly, pre-treatment of mice with antioxidants has been shown to prevent the development of pollen-driven asthma in mice. Interestingly, delaying anti-oxidant treatment until after pollen challenge was ineffective, suggesting that the oxidase activity is of critical importance during the period of innate immune activation. Although the mechanisms remain to be defined, it has been speculated that NADPH oxidase activity initiates immune activation through its ability to recruit inflammatory cells, possibly through the induction of IL-8 by p38 MAPK 74. Of interest, genetic polymorphisms in genes regulating oxidative stress have been shown to be associated with susceptibility to asthma in several populations 75.

Conclusions

Although allergens are a diverse group of molecules, it is becoming increasingly clear that their allergenicity likely resides in their ability to activate various innate immune pathways at mucosal surfaces, rather than in any structural similarities. Complex allergens contain multiple innate immune activating components, which trigger the initial mucosal influx of innate immune cells that subsequently drive Th2-polarized adaptive immune responses. Although the study of innate activating properties of allergens is in its infancy, it is clear that a better molecular understanding of the fundamental origins of allergenicity may well lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies to effectively block allergen recognition and the ensuing inflammatory cascade.

References

- 1.Wills-Karp M. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traidl-Hoffmann C, Jakob T, Behrendt H. Determinants of allergenicity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aalberse RC. Structural biology of allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:228–238. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.108434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas WR, Hales BJ, Smith WA. Structural biology of allergens. Curr Allergy and Asthma Reports. 2005;5:388–393. doi: 10.1007/s11882-005-0012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King C, Brennan S, Thompson PJ, Stewart GA. Dust mite proteolytic allergens induce cytokine release from cultured airway epithelium. J Immunol. 1998;161:3645–3651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan H, et al. Der p1 facilitates transepithelial allergen delivery by disruption of tight junctions. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:123–133. doi: 10.1172/JCI5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun G, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mori L, Mattoli S. Interaction of mite allergens Der p3 and Der p9 with protease-activated receptor-2 expressed by lung epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:1014–1021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat RK, Page K, Tan A, Hershenson MB. German cockroach extract increases bronchial epithelial cell interleukin-8 expression. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kouzaki H, O'Grady SM, Lawrence CB, Kita H. Proteases induce production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by airway epithelial cells through protease-activated receptor-2. J Immunol. 2009;183:1427–1434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kauffman HF, Tamm M, Timmerman JAB, Borger P. House dust mite major allergens Der p 1 and Der p 5 activate human airway-derived epithelial cells by protease-dependent and protease-independent mechanisms. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ring PC, et al. The 18k-Da form of cat allergen Felis domesticus 1 (Fel d 1) is associated with gelatin- and fibronectin-degrading activity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1085–1096. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widmer F, Hayes PJ, Whittaker RG, Kumar RK. Substrate preference profiles of proteases released by allergenic pollens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:571–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeki K, Ozaki K, Kobayashi T, Ito S. Detergent alkaline proteases: enzymatic properties, genes, and crystal structures. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103:501–508. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novey HS, Marchioli LE, Sokol WN, Wells ID. Papain-induced asthma-physiological and immunological features. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979;63:98–103. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(79)90198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kheradmand F, et al. A protease activated pathway underlying Th2 cell type activation and allergic lung disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:5904–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page K, et al. TLR2-mediated activation of neutrophils in response to German cockroach frass. J Immunol. 2008;180:6317–6324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudha VT, Arora N, Singh BP. Serine protease activity of Per a 10 augments allergen-induced airway inflammation in a mouse model. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:507–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kukreja N, Sridhara S, Singh BP, Arora N. Effect of proteolytic activity of Epicoccum purpurascens major allergen, Epi p1 in allergic inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripathi P, Kukreja N, Singh BP, Arora N. Serine protease activity of Cur 11 from Curvularia lunata augments Th2 response in mice. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:292–302. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokol CL, et al. Basophils function as antigen-presenting cells for an allergen-induced T helper type 2 response. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:712–720. doi: 10.1038/ni.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CL, et al. Serine protease inhibitors nafamostat mesilate and gabexate mesilate attenuate allergen-induced airway inflammation and eosinophilia in a murine model of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:105–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Runswick S, Mitchell T, Davies P, Robinson C, Garrod DR. Pollen proteolytic enzymes degrade tight junctions. Respirology. 2007;12:834–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shakib F, Ghaemmaghami AM, Sewell HF. The molecular basis of allergenicity. Trends in Immunology. 2008;29:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt EB, et al. Surfactant protein D alters allergic lung responses in mice and human subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1140–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madan T, et al. Surfactant proteins A and D protect mice against pulmonary hypersensitivity induced by Aspergillus fumigatus antigens and allergens. J Clin Invest. 2001;207:476–475. doi: 10.1172/JCI10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghaemmaghami AM, Gough L, Sewell HF, Shakib F. The proteolytic activity of the major dust mite allergen Der p 1 conditions dendritic cells to produce less interleukin-12: allergen-induced Th2 bias determined at the dendritic cell level. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1468–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, et al. Fungal proteases induce Th2 polarization through limited dendritic cell maturation and reduced production of IL-12. J Immunol. 2008;180:6000–6009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furmonaviciene R, et al. Der p 1 cleaves cell surface DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR: experimental analysis of in silico substrate identification and implications in allergic responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:231–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz O, et al. Proteolytic cleavage of CD25, the a subunit of the human T cell interleukin 2 receptor, by Der p 1, a major mite allergen with cysteine protease activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:271–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz O, et al. Der p 1, a major allergen of the house dust mite, proteolytically cleaves the low-affinity receptor for human IgE (CD23) Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3191–3194. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asokananthan N, et al. Activation of protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1, PAR-2 and PAR-4 stimulates IL-6, IL-8 and prostaglandin E2 release from human respiratory epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2002;16:3577–3585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akers IA, et al. Mast cell tryptase stimulates human lung fibroblast proliferation via protease-activated receptor-2. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:193–201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colognato R, et al. Differential expression and regulation of protease-activated receptors in human peripheral monocytes and monocyte-derived antigen presenting cells. Blood. 2003;102:2645–2652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Andrea MR, Rogahn CJ, Andrade-Gordon P. Localization of protease-activated receptors-1 and -3 in human mast cells; indications for an amplified mast cell degranulation cascade. Biotech Histochem. 2000;75:85–90. doi: 10.3109/10520290009064152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight DA, et al. Protease-activated receptors in human airways: upregulation of PAR-2 in respiratory epithelial cells from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:797–803. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong JH, et al. German cockroach extract activates protease-activated receptor 2 in human airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page K, Strunk VS, Hershenson MB. Cockroach proteases increase IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells via activation of protease-activated receptor-2 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu LL, Perng DW, Yu CH, Su SN, Chow LP. Mold allergen, Pen c13, induced IL-8 expression in human airway epithelial cells by activated protease-activated receptor 1 and 2. J Immunol. 2007;178:5237–5244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebeling C, et al. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 activation in the airways enhances antigen-mediated airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidlin F, et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J Immunol. 2002;169:5315–5321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rallabhandi P, et al. Analysis of proteinase-activated receptor 2 and TLR4 signal transduction: a novel paradigm for receptor cooperativity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24314–2432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804800200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffatt JD, Jeffrey KL, Cocks TM. Protease-activated receptor-2 activating peptide SLIGRL inhibits bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the airways of mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:680–684. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D'Augostino B, et al. Activation of protease-activated receptor-2 reduces airway inflammation in experimental allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1436–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun-Fahrlander C, et al. Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:869–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gehring U, et al. House dust endotoxin and allergic sensitization in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:939–944. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-256OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riedler J, et al. Exposure to farming in early life and development of asthma and allergy: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wills-Karp M, et al. The germless theory of allergic disease: revisiting the hygiene hypothesis. Nature Rev Immunol. 2001;1:69–75. doi: 10.1038/35095579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel O, et al. Effect of inhaled endotoxin on bronchial reactivity in asthmatic and normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1059–1064. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.3.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eisenbarth SC, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1645–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrick CA, Bottomly K. To respond or not to respond: T cells in allergic asthma. Nature Rev Immunol. 2003;3:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nri1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammad H, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pulendran B, et al. Lipopolysaccharides from distinct pathogens induce different classes of immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:5067–5076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Page K, Ledford JR, Zhou P, Wills-Karp M. A TLR2 agonist in German cockroach frass activates MMP-9 release and is protective against allergic inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:3400–3408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heymann PW, et al. Antigenic and structural analysis of group II allergens (Der f II and Der p II) from house dust mites (Dermatophagoides spp) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inohara N, Nuñez G. ML -- a conserved domain involved in innate immunity and lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:219–21. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gruber A, Mancek M, Wagner H, Kirschning CJ, Jerala R. Structural model of MD-2 and functional role of its basic amino acid clusters involved in cellular lipopolysaccharide recognition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28475–28482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trompette A, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Toll dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature. 2006;440:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature04596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jia HP, et al. Endotoxin responsiveness of human airway epithelia is limited by low expression of MD-2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L428–L437. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00377.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomas PG, Carter MR, Da'Dara AA, DeSimone TM, Harn DA. A helminth glycan induces APC maturation via alternative NF-kappa B activation independent of I kappa B alpha degradation. J Immunol. 2005;175:2082–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okano M, Satoskar AR, Nishizaki K, Harn DA., Jr Lacto-N-fucopentaose III found on Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens functions as adjuvant for proteins by inducing Th2-type response. J Immunol. 2001;167:442–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodridge HS, Wolf AJ, Underhill DM. β-glucan recognition by the innate immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shreffler WG, et al. The major glycoprotein allergen from Arachis hypogaea, Ara h 1, is a ligand of dendritic cell-specific ICAM-grabbing non-integrin and acts as a Th2 adjuvant in vitro. J Immunol. 2006;177:3677–3685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rylander R. Airways responsiveness and chest symptoms after inhalation of endotoxin or (1—3)-β-d-glucan. Indoor Built Environ. 1996;5:106–11. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fogelmark B, Thorn J, Rylander R. Inhalation of (1→3)-beta-D-glucan causes airway eosinophilia. Mediators Inflamm. 2001;10:13–19. doi: 10.1080/09629350123707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Inoue K, et al. Candida soluble cell wall beta-glucan facilitates ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice: Possible role of antigen-presenting cells. Respir Res. 2009;10:68. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nathan AT, Peterson EA, Chakir J, Wills-Karp M. Innate immune responses of airway epithelium to house dust mite are mediated through beta-glucan-dependent pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barrett NA, Maekawa A, Rahman OM, Austen KF, Kanaoka Y. Dectin-2 recognition of house dust mite triggers cysteinyl leukotriene generation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1119–1128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deslée G, et al. Involvement of the mannose receptor in the uptake of Der p 1, a major mite allergen, by human dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:763–70. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.129121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chieppa M, et al. Cross-linking of the mannose receptor on monocyte-derived dendritic cells activates an anti-inflammatory immunosuppressive program. J Immunol. 2003;171:4552–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boldogh I, et al. ROS generated by pollen NADPH oxidase provide a signal that augments antigen-induced allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2169–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI24422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dharajiya N, Choudhury BK, Bacsi A, Boldogh I, Alam R, Sur S. Inhibiting pollen reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-induced signal by intrapulmonary administration of antioxidants blocks allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, Choudhury BK, Sur S, Boldogh I. Effect of pollen-mediated oxidative stress on immediate hypersensitivity reactions and late-phase inflammation in allergic conjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Islam T, et al. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) P1, GSTM1, exercise, ozone and asthma incidence in school children. Thorax. 2009;64:197–202. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.099366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]