Abstract

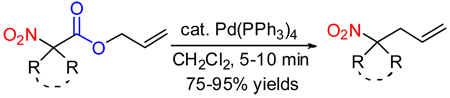

Allyl nitroacetates undergo decarboxylative allylation to provide tertiary nitroalkanes in high yield. Moreover, the transformations are complete within several minutes under ambient conditions. High yields result because O-allylation of the intermediate nitronates, which is typically problematic, is reversible under conditions of the decarboxylative allylation process. Lastly, the preparation of substrate allyl nitroacetates by tandem Knoevenagel/Diels-Alder sequences allows the facile synthesis of relatively complex substrates that undergo diastereoselective decarboxylative allylation.

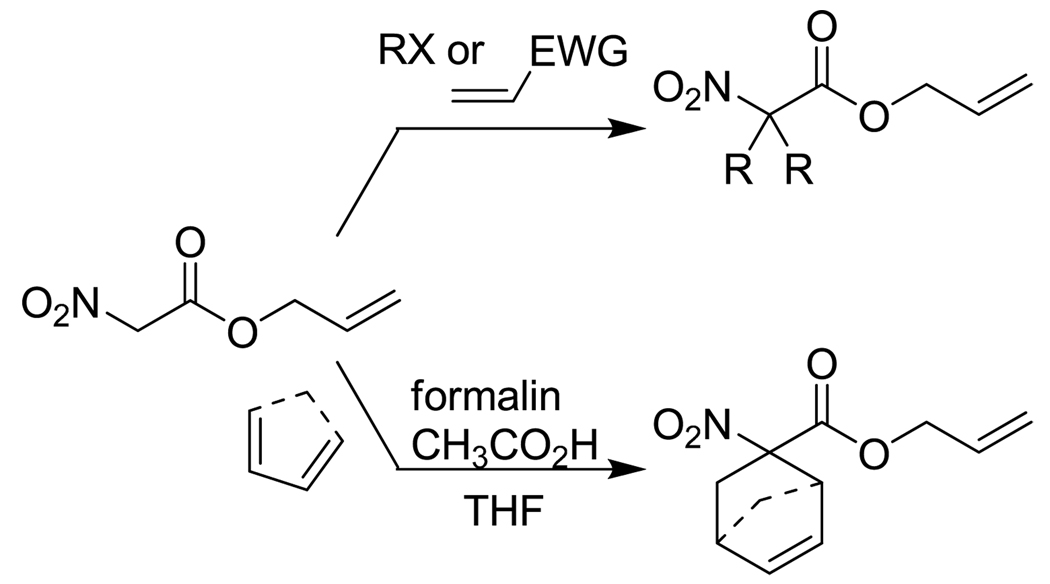

The development of new reactions that allow the incorporation of nitrogen into useful building blocks is a necessity for more efficient synthesis of alkaloids and other biologically active nitrogenous compounds. With this in mind, the synthesis of homoallylic amines1 has been given great attention due to their synthetic flexibility. Previously, we developed a decarboxylative coupling of α-amino acid derivatives that gave rise to protected homoallylic amines2 and Chruma has developed a similar coupling that provides simple access to a variety of non-natural amino acid substrates.3,4 That said, the decarboxylative coupling of amino acid esters exhibits poor regioselectivity and thus does not allow the efficient formation of tertiary amines (eq. 1). Herein we report an efficient palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling of allyl α-nitro acetates that provides access to α-tertiary homoallylic amines.

While there are numerous publications on the use of highly stabilized nitroenolates (pKa ~ 8 in DMSO) in Tsuji-Trost type allylations,5 there are currently few

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

effective methods for allylating nonstabilized nitronates (pKa ~ 17 in DMSO).6,7 An extensive early study showed that even moderately sterically demanding nitronates suffer from competing O-allylation and thus low yields of C-allylation products.6 More recently, Shibasaki developed an improved procedure to facilitate C-allylation, however that reaction requires base additives and long (48 h) reaction times at 50 °C for most substrates.7

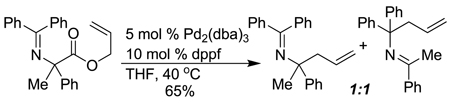

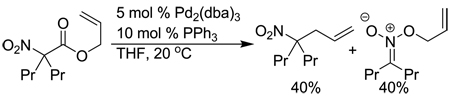

In 1987, Tsuji reported a single example of the decarboxylative coupling of a nitroacetic ester that indicated that decarboxylative coupling would allow the rapid synthesis of tertiary homoallylic amine precursors under mild conditions without added base (eq. 2).8 Unfortunately, the reaction was plagued by competing O-allylation. The amount of O-allylation could be somewhat reduced at −50 °C, but C-allylation was still favored only by a 2:1 ratio. Thus, to begin developing a synthetically useful method, it was necessary to explore reaction conditions that would provide high yields of C-allylation product and minimize the amount of O-allylation.

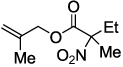

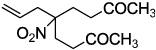

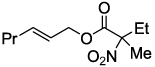

Toward that end, a simple allyl α,α-dialkyl nitroacetate was synthesized and evaluated in decarboxylative coupling. To our delight, the decarboxylative coupling of 1a in CH2Cl2 solvent proceeded quickly and cleanly in the presence of 5 mol% Pd(PPh3)4 to form the desired C-allylated nitroalkane in high yield (Scheme 1).9 Moreover, the reaction was very rapid, forming product in just 5 minutes at room temperature; to generate a comparable yield of such a product using known methodology would require 78 h at 15 °C6 or 48 h at 25 °C7 depending on the method of choice.10

Scheme 1.

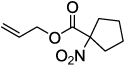

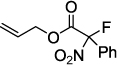

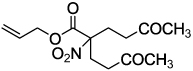

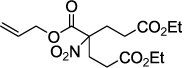

Next, we chose to explore more sterically demanding nitronates that can prove to be problematic due to competing O-allylation. As can be seen in table 1, simple α,α-dialkyl nitroacetates react to provide good yields of the nitroalkane products. In every case, the reactions were complete within 10 min. at 25 °C. Due to these mild conditions, the reaction is tolerant of functionality including α-fluorination (entry 3) as well as pendant esters (entries 5–6) or ketones (entry 4). Lastly, when unsymmetrical allyls are utilized, the decarboxylative coupling is highly regioselective in favor of the linear regioisomer (entries 7–8). Importantly, the aliphatic allylic alcohol derivative shown in entry 8 undergoes reaction without observable elimination.

Table 1.

Decarboxylative coupling of nitroalkanes

| entry | substract | product | yield(%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

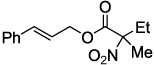

| 1 |  |

|

2b 81 |

| 2 |  |

|

2c 90 |

| 3 |  |

2d 90 | |

| 4 |  |

|

2e 88 |

| 5 |  |

2f 92 | |

| 6 |  |

|

2g 93 |

| 7 |  |

2h 87b,c | |

| 8 |  |

2i 83c |

isolated yield, 0.2 M substrate in CH2Cl2, 5 mol % Pd(PPh3)4, rt 10 min

10 mol % Pd(PPh3)4

>20:1 l:b

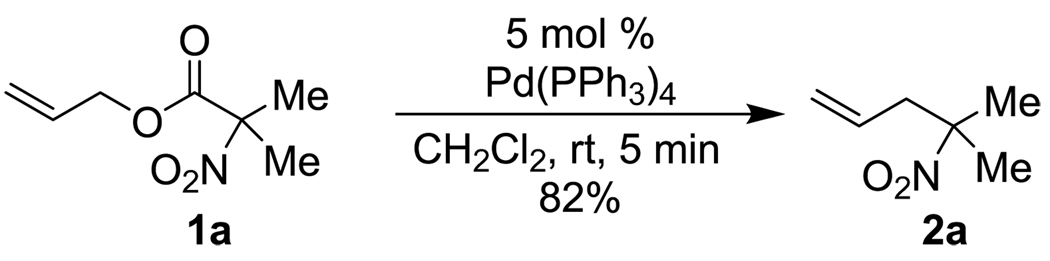

It is also noteworthy that the cinnamyl derivative 1h performed better under conditions at higher catalyst loadings (10 mol %); at 5 mol % a significant amount of cinnamaldehyde was formed instead of desired allylated nitroalkane (1.5:1 2h:RCHO).6 The cinnamaldehyde is most likely derived from the O-allyl nitronate via elimination (Scheme 2).6 Thus, in the case of 1h, we observe less O-allylation at higher catalyst loading. This suggests that palladium plays a direct role in conversion of the O-allylated intermediate (B) to the C-allylated product (2h). Such behavior can be rationalized if one proposes that O-allylation is reversible. In such a case palladium can engage the O-allyl nitronate (B) to reform intermediate π-allyl complex (A) which then produces C-allyl product (Scheme 2). Thus, the Pd concentration needs to be high enough that the bimolecular π-allyl palladium formation from the O-allyl nitronate is faster than unimolecular elimination to form cinnamaldehyde. This hypothesis suggests that reactions that are run at higher concentration should produce more C-allylation product (2h) and reduce the amount of cinnamaldehyde. Indeed, when the decarboxylative allylation is run with 5 mol% Pd(PPh3)4, the ratio of 2h:RCHO improves from 1.2:1 to 2.2:1 on increasing the concentration of 1h from 0.05 M to 0.1 M. A further improvement to 4.5:1 2h:RCHO is achieved at 0.3 M substrate. These results suggest that high yields of C-allylation products can result from favoring rapid reversible O-allylation rather than by avoiding O-allylation.

Scheme 2.

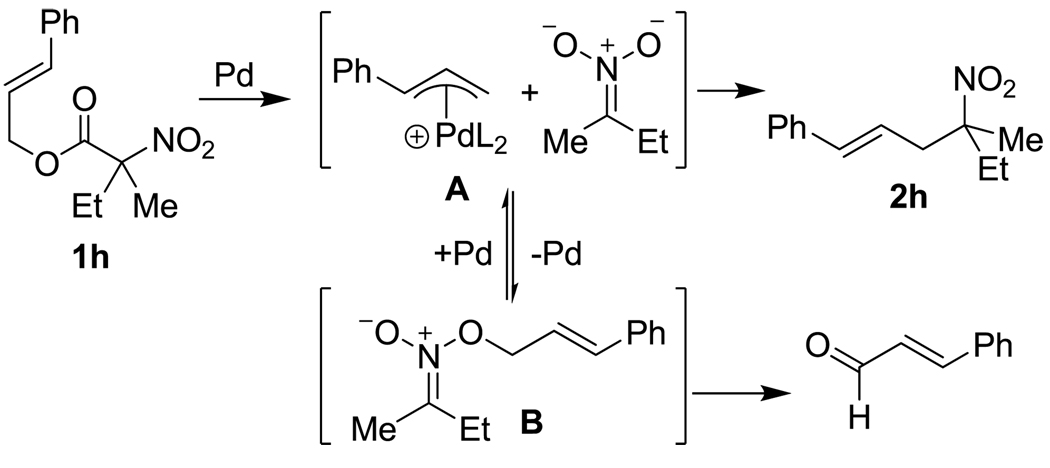

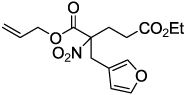

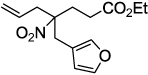

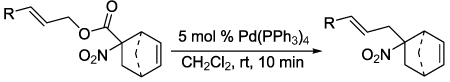

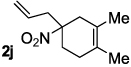

Aside from the rapid, base-free reactions, a significant advantage of decarboxylative allylation is the ability to construct the desired nucleophile prior to coupling (Scheme 3). This process is facilitated by the acidity of the α-hydrogens, which allows one to use acetoacetic ester-type synthesis to rapidly provide derivatives. In addition, one can rapidly access more complex substrates via tandem Knoevenagel condensation/Diels-Alder cycloaddition chemistry (Scheme 3).11

Scheme 3.

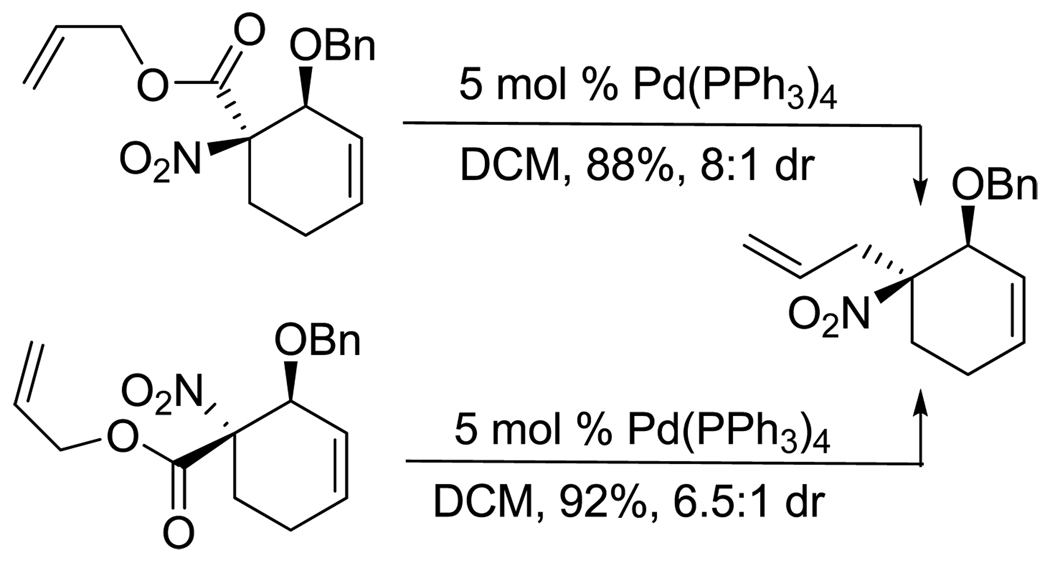

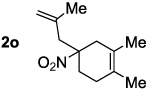

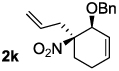

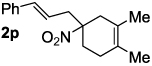

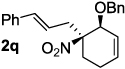

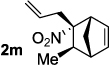

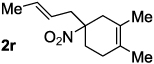

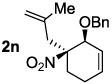

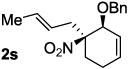

Decarboxylative allylation of the substrates generated by Knoevenagel/Diels-Alder chemistry provides high yields of the allylated nitro alkanes (table 2). Once again, both aryl (2p,2q) and alkyl-substituted (2r,2s) allyl groups are excellent reaction partners in this chemistry. In addition, these substrates also allow us to explore the diastereoselectivity of allylation; the 1,2-diastereoselectivity of decarboxylative allylations has not been systematically investigated. As can be seen from examples 2k, 2l and 2m, 1,2-stereocontrol favors the anti- or exo-allylation, suggesting a sterically controlled allylation. Lastly, the decarboxylative allylation is stereoconvergent, so both diastereomers of the reactant form the product with the same relative stereochemistry (Scheme 4). Thus, even poorly selective Diels-Alder reactions can give rise to diastereoenriched products.12

Table 2.

Diels-Alder/Decarboxylative Coupling

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| product | yield (dr) | product | yield (dr) |

|

90% |  |

91% |

|

92% (6.5:1) |  |

93%a |

|

95% (8:1) |  |

97% (6.5:1)a |

|

90% (6:1) |  |

91%b |

|

75% (6.5:1) |  |

82% (7:1)c |

10 mol % Pd(PPh3)4 l:b = >20:1

l:b = 3.3:1

l:b = 5:1

Scheme 4.

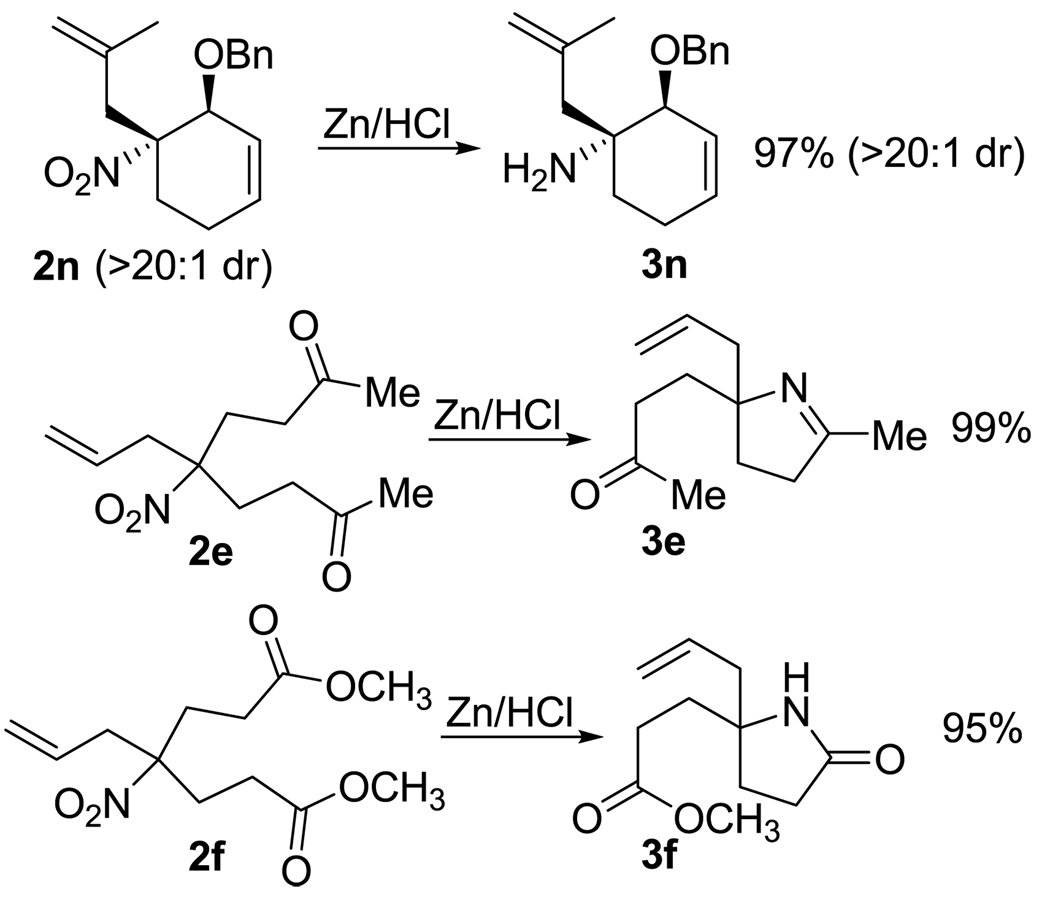

As expected, the resulting allylated nitroalkanes are excellent precursors to homoallylic amine derivatives. Simple reduction using zinc dust and HCl gives rise to homoallylic amines, while reductions of appropriately substituted derivatives proceed directly to heterocyclic analogs (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

In conclusion, we have developed a practical decarboxylative allylation of nitroalkanes that provides rapid access to a variety of homoallylic amine derivatives. High yields are obtained by using a catalyst/solvent combination wherein O-allylation is rapid and reversible, thus favoring the irreversible C-allylation process. Lastly, the diastereoselectivity of the allylation suggests that the allylation process occurs with simple steric control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Institute of General Medical Science (1R01GM079644) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews of allylation of aldimines see:Ding H, Friestad GK. Synthesis. 2005:2815–2829.Shibasaki M, Kanai M. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2853–2873. doi: 10.1021/cr078340r.

- 2.Burger EC, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10002–10003. doi: 10.1021/ja063115x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeagley AA, Chruma JJ. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2979–2882. doi: 10.1021/ol071080f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Shimizu I, Yamada T, Tsuji J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980:3199. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuda T, Chujo Y, Nishi S-i, Tawara K, Saegusa T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6381. [Google Scholar]; (c) Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14860–14861. doi: 10.1021/ja077070r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Weaver JD, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4657–4660. doi: 10.1021/ol801951e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono N. The Nitro Group in Organic Synthesis. New York, NY: Feuer, H.; Wiley-VCH; 2001. pp. 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Aleksandrowicz P, Piotrowska H, Sas W. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:1321–1327. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wade PA, Morrow SD, Hardinger SA. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:365–367. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4250–4257. Isolated yields were not reported. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuji J, Yamada T, Minami I, Yuhara M, Nisar M, Shimizu I. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:2989–2995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pd2(dba)3 with the chelating ligand (rac)-BINAP failed to give any conversion under these conditions.

- 10.Allylation of α-bromo nitroalkanes with allylstannanes:Ono N, Zinmeister K, Kaji A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1985;38:1069–1070.

- 11.Wade PA, Murray JK, Jr, Shah-Patel S, Carroll PJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:2585–2588. [Google Scholar]

- 12.See supporting information for a table of substrate and product dr’s.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.