Abstract

Situs is a modular and widely used software package for the integration of biophysical data across the spatial resolution scales. It has been developed over the last decade with a focus on bridging the resolution gap between atomic structures, coarse-grained models, and volumetric data from low-resolution biophysical origins, such as electron microscopy, tomography, or small-angle scattering. Structural models can be created and refined with various flexible and rigid body docking strategies. The software consists of multiple, stand-alone programs for the format conversion, analysis, visualization, manipulation, and assembly of 3D data sets. The programs have been ported to numerous platforms in both serial and shared memory parallel architectures and can be combined in various ways for specific modeling applications. The modular design facilitates the updating of individual programs and the development of novel application workflows. This review provides an overview of the Situs package as it exists today with an emphasis on functionality and workflows supported by version 2.5.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12551-009-0026-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Structural models, 3D data sets, Multi-platform, Modeling

Introduction

Scientific computing, including modeling and simulation, is crucial for solving biophysical research problems that are beyond the reach of traditional theoretical and experimental approaches (U.S. Department of Energy 2005). Originally confined to a supporting role with respect to experimental or theoretical approaches, modeling and simulation are increasingly seen as capable of creating new evidence in their own right (Lee et al. 2009). Computer-generated hypotheses can be confirmed or refuted, like their experimental or theoretical counterparts, even though the virtual (in silico) world is at best an imperfect mirror of the physical (in vivo) world.

In the late 1990s, funding agencies in the biological sciences took notice of this opportunity. In April 1998, a special Cell Biology and Biophysics Subcommittee of the U.S. National Advisory General Medical Sciences Council examined research trends in the areas of molecular cell biology, structural biology, and biophysics. Among the needs identified by the panel were better (computational) methods for structural analysis of large macromolecular assemblies and imaging macromolecules in cells. Based in part on these recommendations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a new program announcement that altered the more traditional biological hypothesis-driven review and award criteria in favor of method development (National Institutes of Health 2000). Instead of the traditional proposal style, biophysical scientists in the U.S. could for the first time submit applications based solely on the merit of computational techniques. This paradigm shift was important for the advancement of computational biology, because opportunities for funding computational research had hitherto existed mainly in the physical sciences (U.S. Department of Energy 2005).

Against the backdrop of the emerging research opportunities in computational biophysics, the Situs package was created for the modeling and simulation of large biomolecular assemblies at variable resolution scales. Situs was initially conceived as a platform for the dissemination of structural coarse-graining algorithms to the biophysical community. Powerful experimental techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy (Baker and Johnson 1996), tomography (Medalia et al. 2002), and small-angle scattering (Niemann et al. 2008), which routinely produced 3D structures at a reduced spatial resolution, had emerged. These methods were capable of yielding low-resolution density maps under a wide range of biochemical conditions that allow atomic structures of components to be fitted and docked (Baker and Johnson 1996; Wriggers and Chacón 2001b), and they were in need of software to help integrate the structural data.

The goal of Situs is to characterize the structure and functionally relevant motions of biomolecular systems by integrating experimental data across the resolution scales, using advanced algorithms from neurocomputing, image processing, and visualization. A decade has passed since the publication of the original Situs paper (Wriggers et al. 1999). This review will assess the software as it is used by scientists today. Naturally, the workflow has changed in many ways over the years as compatible molecular graphics programs have evolved and Situs tools have been enhanced, updated, or replaced.

The following sections highlight the current Situs workflow using published usage examples kindly provided by other laboratories. In the first section, a typical correlation-based docking approach in electron microscopy (EM) is described, using the recent model of the influenza virus ribonucleoprotein complex (Coloma et al. 2009) as an example. Next, the integration of structural data with small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data is shown on models of the extracellular region of an EGF receptor family member, s-dEGFR (Alvarado et al. 2009). Finally, a flexible fitting approach is shown using coarse-grained resolution models of myosin. Personal comments and annotations by the author are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

Correlation-based docking in electron microscopy

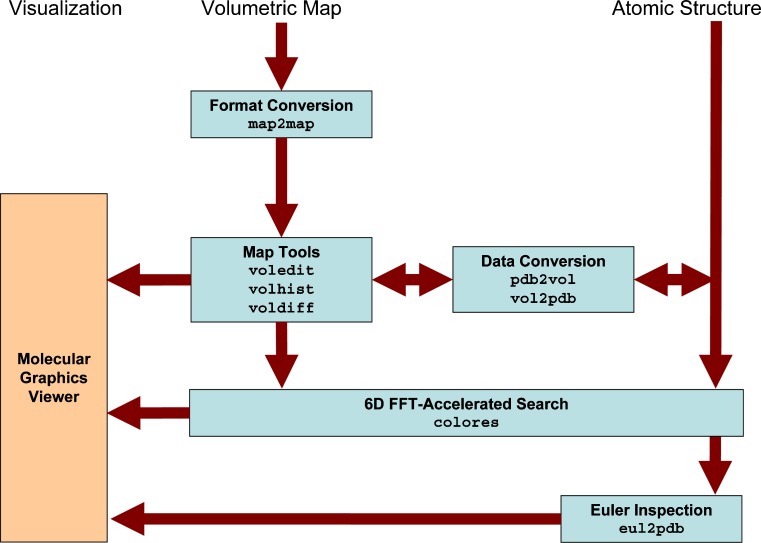

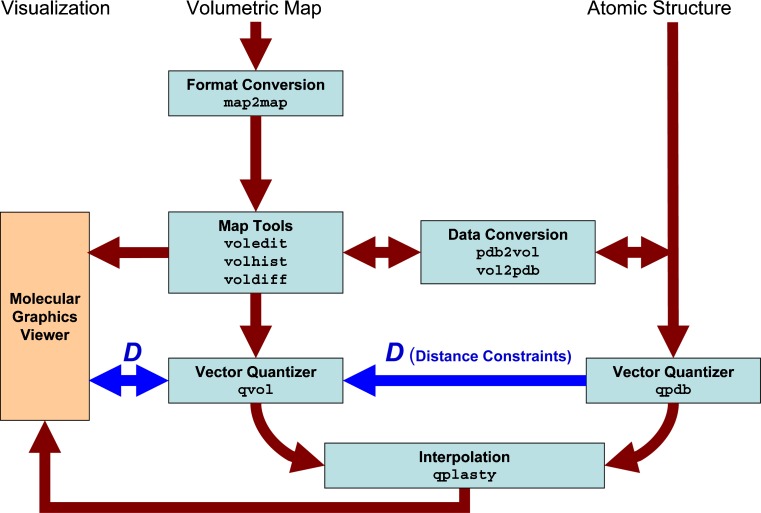

Chacón and Wriggers (2002) introduced colores, a widely used registration tool that takes advantage of Fourier correlation theory to rapidly scan the six translational and rotational degrees of freedom of a probe molecule relative to a (fixed) target density map. X-ray crystallographic fitting methods, based on volumetric cross-correlation or the free R-value, are limited to resolutions <10 Å where densities exhibit internal structure. The major advantage of colores is that it extends the viable resolution range to ∼30 Å by means of a Laplacian operator that emphasizes contour (shape) information in addition to the traditional correlation. Over the years, we have optimized the efficiency and accuracy of colores and ported the tool to shared memory environments that take advantage of today’s multi-core architectures. The series of steps and the programs that are required to use colores for the docking of a probe structure to a target EM map are shown schematically in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of colores-related routines in Situs 2.5. Major Situs components (blue) are classified by their functionality. The main workflow is indicated by brown arrows. The visualization (orange) for the rendering of the models requires a molecular graphics viewer such as VMD (Humphrey et al. 1996), Chimera (Pettersen et al. 2004), or Sculptor (http://sculptor.biomachina.org). Standard volumetric map formats are converted to cubic lattices in Situs format with the map2map utility. Subsequently, the data are inspected and, if necessary, prepared for the fitting using a variety of visualization and analysis tools. Situs docking tools require one volume (target) and one PDB structure (probe). Atomic coordinates in PDB format can be transformed to low-resolution maps, if necessary, and vice versa, to allow the docking of maps to maps or structures to structures. The resulting docked complex can be inspected in the graphics program. In addition, if a subset of Euler angles is chosen, these can be inspected (after conversion into PDB format) with the eul2pdb tool.

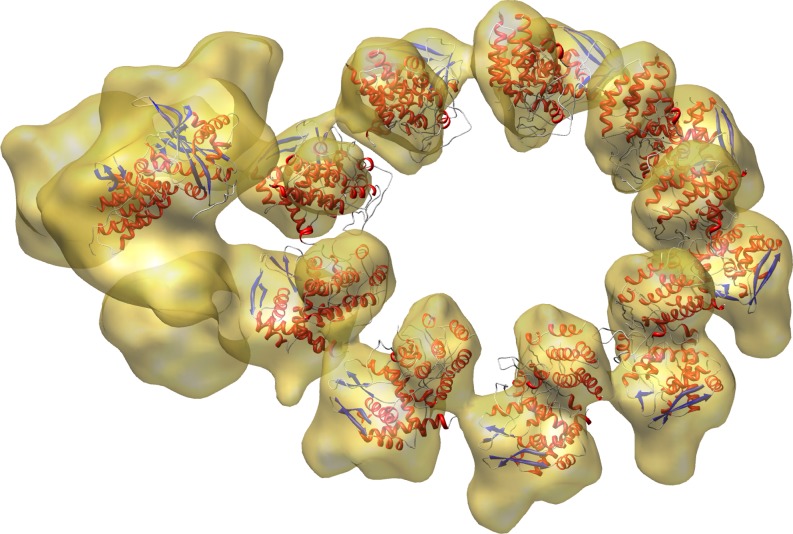

Recently, colores was successfully used in the modeling of a biologically active influenza virus ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (Coloma et al. 2009). The RNP particles of influenza A viruses are formed by the association of single-stranded RNA to multiple monomers of nucleoprotein (NP) and a single copy of the polymerase complex composed by the PB1, PB2, and PA subunits. Coloma et al. (2009) succeeded in building a 3D model of RNP by assembling 3D reconstructions from a non-symmetrical complex containing the polymerase (at 18 Å resolution) with the NP ring derived from a symmetrical volume (at 12 Å resolution). The docking of the atomic structures of NP and partial structures of PB1 and PA in this chimera map is shown in Fig. 2. The result, described in more detail by Coloma et al. (2009), is the first structural model for a functional viral RNP complex.

Fig. 2.

Docking of the partially solved PA-PB1 complex (left) and NP (ring) monomers into the RNP structure (transparent) using colores. The graphic, kindly provided by Jaime Martín-Benito Romero, visually combines the results of Figs. 2–4 of Coloma et al. (2009)

Visualization and modeling of small-angle scattering data

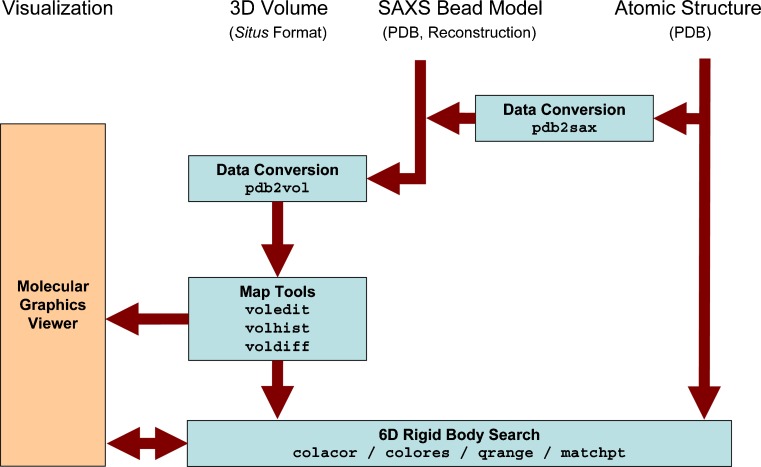

3D bead models of proteins in solution can be determined from 1D scattering data, in particular from SAXS (Chacón et al. 2000). Wriggers and Chacón (2001a) extended existing Situs tools to provide an atomic interpretation of SAXS-derived shapes. The workflow and the programs that are used to dock an atomic structure into low-resolution SAXS models are shown schematically in Fig. 3. The bead models can be transformed into volumetric maps for subsequent docking using convolution with a hard sphere kernel (pdb2vol tool). The SAXS modeler then has access to all docking strategies supported by Situs, including correlation-based docking (colacor/colores) and point cloud matching (qrange/matchpoint), and even flexible fitting (see below). To test the docking accuracy, we added the pdb2saxs tool to map atomic structures of trial proteins to hexagonal close-packed lattices with variable bead radii. The resulting models served as “simulated” low-resolution data in Wriggers and Chacón (2001a): For >100 beads typically arising in SAXS models, a rigid body docking precision can be achieved of the order of an Angstrom.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of SAXS-related routines in Situs 2.5. Visualization and modeling of atomic structures into SAXS bead models are supported through a conversion into 3D volumes representing the beads using the pdb2vol kernel convolution tool. Docking between atomic structures and 3D maps can be achieved through a number of approaches (see text). The data can be prepared further for the visualization using a variety of analysis and editing tools. Optional Gaussian kernel convolution with pdb2vol facilitates the smoothing of bead surfaces for their visualization in the form of density isocontours

Another specific problem in the interpretation of SAXS data is the visualization of the beads. We found it useful to render not the densely packed beads themselves, but rather an envelope that can be created by isocontouring a volumetric map that was created by convolution with a soft kernel such as a Gaussian (using pdb2vol).

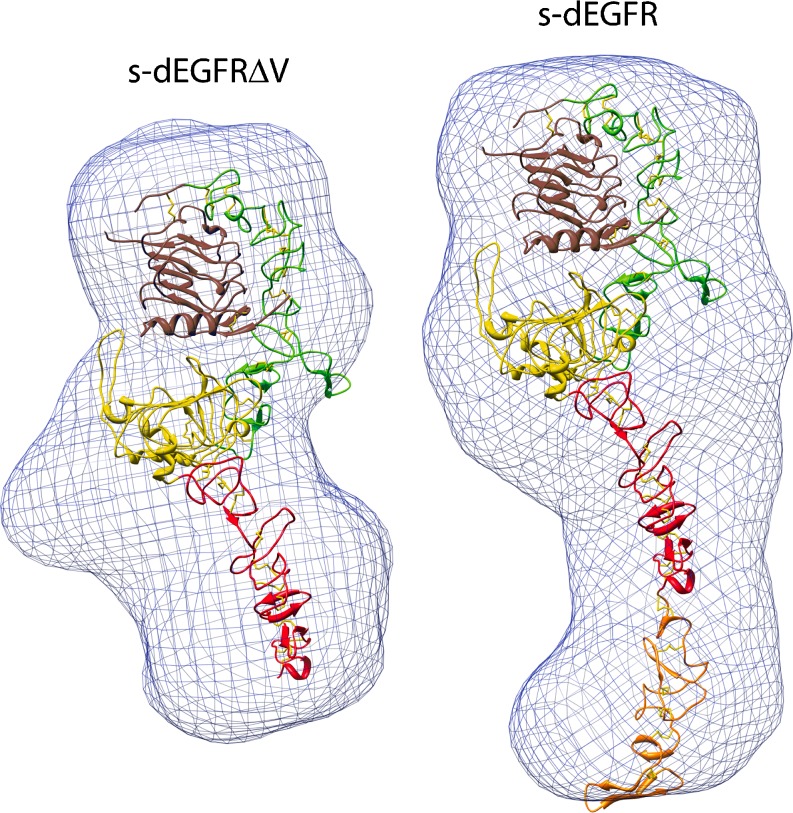

Our approach to rendering and interpretation of SAXS data has been adopted by other groups (Lipfert et al. 2007; Fagan et al. 2009). Here, we highlight a recent Nature article on structural studies of the single epidermal growth factor receptor family member (dEGFR) in Drosophila melanogaster. Alvarado et al. (2009) determined the 2.7 Å X-ray crystal structure of the unliganded dEGFR extracellular region, encompassing domains I to IV (s-dEGFRΔV). A structural overlay of an active, extended, receptor tyrosine kinase sErbB2 and s-dEGFRΔV showed them to be remarkably similar, with important functional implications. One key question was whether crystal packing causes s-dEGFRΔV to be extended. This hypothesis was ruled out by SAXS studies of s-dEGFRΔV and complete s-dEGFR (Fig. 4). The Situs-derived models, shown in Fig. 4, indicate that s-dEGFRΔV is extended in solution (the envelope readily encompasses the crystal structure), and that domain V (orange) simply projects from the end of domain IV (red) to extend the structure further.

Fig. 4.

Low-resolution molecular envelopes from SAXS studies of s-dEGFRΔV (left) and s-dEGFR (right). The envelopes (blue), created after kernel convolution with pdb2vol, readily accommodate the Situs-docked crystallographic models (see text). The graphic, kindly provided by Diego Alvarado and Mark Lemmon, emphasizes interior domain details; see also Fig. 2b in Alvarado et al. (2009)

Flexible fitting

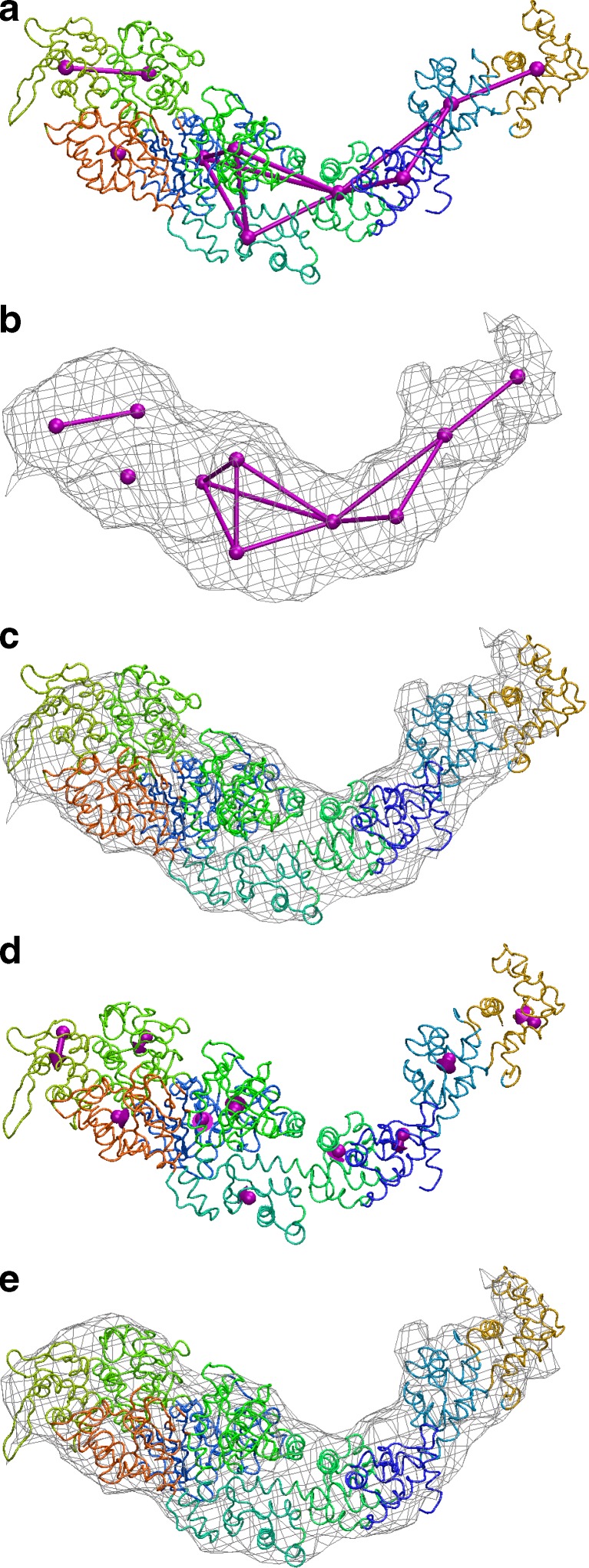

Rigid-body docking, as described above, laid the groundwork for the development of a flexible docking technique that brings deviating features of multi-resolution structures into register. In such situations, the atomic structure is moved towards the target density by systematically reducing the rms deviation between coarse-grained control points in a refinement of the atomic structure. One of the open questions in flexible docking is how to maintain the stereochemical quality of a fitted structure, since any over-fitting to noisy experimental data would compromise the quality of the atomic model. In an earlier review article (Wriggers et al. 2004), we described the details of a significant improvement to our flexible fitting algorithm, the Motion Capture Network (MCN). The basic idea of the workflow, depicted in Fig. 5, is that lateral connections (distance constraints) are formed between control points that reflect the connectivity of the biological polypeptide chain. This approximation of the movement can be justified by the statistics of biomolecular domain motions documented in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). In the following, a (previously unpublished) modeling of the actomyosin complex illustrates MCN-based flexible fitting.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of flexible fitting with Situs 2.5. The modeling of distance constraints for the MCN is shown in dark blue. Standard volumetric map formats are converted with the map2map utility and the data can be prepared for coarse graining by vector quantization using a variety of map visualization and analysis tools. Atomic coordinates in PDB format can be transformed to low-resolution maps, if necessary, and vice versa. During vector quantization of the high-resolution structure, distances can be learnt that are sent to the vector quantizer of the low-resolution structure to enable MCN-based fitting. After the vector quantization, the high-resolution structure is flexibly docked by the qplasty tool (Rusu et al. 2008). As an alternative to spatial interpolation with qplasty, a molecular dynamics refinement is also supported

An atomic model of F-actin (Holmes et al. 2003) was fitted to the 14 Å resolution actomyosin map (data kindly provided by Rasmus R. Schröder, now at University of Heidelberg, during his visit to Houston in 2003). The F-actin structure allowed us to create a mask for a single myosin S1 unit by low-pass filtering from the docked atomic structure using pdb2vol. As described by Wriggers and Chacón (2001b), the mask was needed by the tools voledit and voldiff to segment and subtract densities from actin and neighboring symmetry-related subunits and to obtain the density of a single myosin S1 from the helical 3D map. This single myosin S1 map was then compared to the atomic structure.

We first attempted rigid-body fitting of the atomic model, taken from the supplementary structure “motor domain.pdb” (Holmes et al. 2003), into the 3D map with colores, as described above. Rigid-body docking was not satisfactory with respect to the position of the upper 50K domain and the lever arm, even when performed independently for each structural subunit. Therefore, we subjected the predicted atomic model to flexible docking (Fig. 6) to characterize the observed changes. The flexible docking procedure was based on a connected MCN of identified features within the atomic model (Wriggers et al. 2004). The atomic model was allowed to move according to displacements tracked by 10 control points defined by the network, to find the best match to the cryo-EM map. The number of control points was judged to be sufficient for capturing the shape details of the single S1 map that occupies a volume of 185,000 Å3 at the isocontour level shown (Fig. 6). The number of independent pieces of information contained in the 14 Å resolution map is then 185,000/143 ≈ 67. This number comprises an upper bound for the number of recognizable features in this particular volume. The conservative choice of 10 points (corresponding to a spatial resolution of 26 Å in the reduced network) was significantly below this upper bound to avoid an over-fitting of the data (Wriggers and Chacón 2001b). This level of detail, however, was quite sufficient for the flexing.

Fig. 6.

Flexible fitting of myosin 2 subfragment 1. a MCN (see text) and Voronoi tessellation of the atomic structure. b MCN fitted to the segmented EM density. c Before flexing. d Displacements sampled at the control points. e After flexing

The longitudinal distance constraints in the MCN were assigned manually, as described by Wriggers et al. (2004), by following the connectivity of the polypeptide chain and to ensure robustness of the control points during the shape change. We found by trial and error that motion capture was best achieved through allocating more flexibility to the 50K regions (effectively allowing cleft closure) by eliminating all constraints on the motion of control points in this region. The final network used for the automated flexing is shown in Fig. 6.

We performed the flexing by adding a constraint energy function to the Hamiltonian of a molecular dynamics simulation that penalizes global shape differences between the data sets (Wriggers et al. 2004). In the molecular dynamics run, we added water molecules predicted by DOWSER (Zhang and Hermans 1996) to the system, which resulted in a total system size of 12,008 atoms.

One can expect that at 14 Å resolution the flexing faithfully reproduces conformational differences with a precision of 2 Å if atomic structures are locally conserved (Wriggers et al. 2004). Side chains are rearranged automatically to accommodate global conformational changes. Otherwise, the algorithm leaves the initial structure intact at the local level. Whether this assumption holds depends on the nature of the conformational difference between the two isoforms, which is not known a priori. However, it has been shown that only about 7% of protein domain rearrangements documented in the PDB are irregular motions where the tertiary structure is significantly perturbed (Gerstein and Krebs 1998). Therefore, it is plausible, at least for the predominantly hinge-type domain motions exhibited by myosin, that the low-resolution flexible fitting approach visualizes conformational changes with a precision of single amino acid residues. The final flexing-induced rms deviation in the atomic model was 5.3 Å.

To validate the precision and probe for systematic errors, we also performed a control flexing calculation on the structure of myosin 5 (Coureux et al. 2003). Myosin 5 is deemed to be in closer agreement with the 3D map of S1 in actomyosin (Holmes et al. 2004). Following the above protocols, we created a model of myosin 5, resulting in a total system size of 11,150 atoms. The observed flexing-induced rms deviation in the atomic model was 3.8 Å, which was indeed much lower than that observed in the myosin 2 case.

The above tests validate the Situs-based flexible fitting approach with a real EM data set. More detailed and systematic tests of flexible fitting were published in Rusu et al. (2008). In addition, the myosin fitting was recently extended to full thick filaments of tarantula muscle in collaboration with the group of Raúl Padrón in Venezuela (Alamo et al. 2008).

Conclusion

One key to the success of Situs over the years has been that the programs were ported to multiple platforms and their source code was freely available on the Internet (http://situs.biomachina.org). While we strive to teach at workshops and symposia, it seems that many researchers prefer to explore software in their own laboratories.

Our web-based tutorials have helped hundreds of electron microscopists and small- angle scattering experts to learn the use of the programs. For their dissemination, we obtained our own web domain (http://biomachina.org) and web server.

Another helpful aspect was the modular design of the programs. As mentioned above, the software consists of multiple, stand-alone tools that can be combined in various creative ways. The modular design allowed us to update individual programs over time (inevitably, it becomes necessary to update algorithms and to implement bug fixes for problems reported to us). We are managing an e-mail list to communicate with the more than 2,000 registered users who opted to receive information. Readers should feel free to send comments to situs@biomachina.org.

This brief review primarily focused on the scientific use of the software, but the development of Situs was also a personal journey for the author, with many memorable encounters along the way. A personal history of this work, as well as annotated references, can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 269 kb)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jaime Martín-Benito Romero, Diego Alvarado, and Mark Lemmon for providing Figs. 2 and 4, and for critical reading of this manuscript. In addition, I thank Rasmus R. Schröder and Kenneth C. Holmes for discussions. This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (R01GM62968), the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (BR-4297), and the Human Frontier Science Program (RGP0026/2003).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Alamo L, Wriggers W, Pinto A, Bártoli F, Salazar L, Zhao F-Q, Craig R, Padrón R. Three-dimensional reconstruction of tarantula myosin filaments suggests how phosphorylation may regulate myosin activity. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:780–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado D, Klein DE, Lemmon MA. ErbB2 resembles an autoinhibited invertebrate epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature. 2009;461:287–291. doi: 10.1038/nature08297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TS, Johnson JE. Low resolution meets high: towards a resolution continuum from cells to atoms. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:585–594. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(96)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón P, Wriggers W. Multi-resolution contour-based fitting of macromolecular structures. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:375–384. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón P, Díaz JF, Morán F, Andreu JM. Reconstruction of protein form with X-ray solution scattering and a genetic algorithm. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1289–1302. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coloma R, Valpuesta JM, Arranz R, Carrascosa JL, Ortín J, Martín-Benito J. The structure of a biologically active influenza virus ribonucleoprotein complex. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000491. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureux PD, Wells AL, Menetrey J, Yengo CM, Morris CA, Sweeney HL, Houdusse A. A structural state of the myosin V motor without bound nucleotide. Nature. 2003;425:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature01927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan RP, Albesa-Jové D, Qazi O, Svergun DI, Brown KA, Fairweather NF. Structural insights into the molecular organization of the S-layer from Clostridium difficile. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1308–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein M, Krebs W. A database of macromolecular motions. Nucl Acids Res. 1998;26:4280–4290. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KC, Angert I, Kull FJ, Jahn W, Schröer RR. Electron cryo- microscopy shows how strong binding of myosin to actin releases nucleotide. Nature. 2003;425:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature02005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KC, Schröder RR, Sweeney HL, Houdusse A. The structure of the rigor complex and its implications for the power stroke. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2004;359:1819–1828. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey WF, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Hsin J, Sotomayor M, Comellas G, Schulten K. Discovery through the computational microscope. Structure. 2009;17:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert J, Das R, Chu VB, Kudaravalli M, Boyd N, Herschlag D, Doniach S. Structural transitions and thermodynamics of a glycine-dependent riboswitch from Vibrio cholerae. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia O, Weber I, Frangakis AS, Nicastro D, Gerisch G, Baumeister W. Macromolecular architecture in eukaryotic cells visualized by cryoelectron tomography. Science. 2002;298:1209–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1076184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Technology development for high-resolution electron microscopy (PA-00-084). URL http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/pa-00-084.html (accessed 10/15/2009). 2000

- Niemann HH, Petoukhov MV, Härtlein M, Moulin M, Gherardi E, Timmins P, Heinz DW, Svergun DI. X-ray and neutron small-angle scattering analysis of the complex formed by the Met receptor and the Listeria monocytogenes invasion protein InlB. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comp Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusu M, Birmanns S, Wriggers W. Biomolecular pleiomorphism probed by spatial interpolation of coarse models. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2460–2466. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy (2005) Energy department requests proposals for advanced scientific computing research. URL http://www.energy.gov/news/2823.htm (accessed 10/15/2009)

- Wriggers W, Chacón P. Using Situs for the registration of protein structures with low-resolution bead models from X-ray solution scattering. J Appl Cryst. 2001;34:773–776. doi: 10.1107/S0021889801012869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers W, Chacón P. Modeling tricks and fitting techniques for multi-resolution structures. Structure. 2001;9:779–788. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers W, Milligan RA, McCammon JA. Situs: A package for docking crystal structures into low-resolution maps from electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:185–195. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers W, Chacón P, Kovacs J, Tama F, Birmanns S. Topology representing neural networks reconcile biomolecular shape, structure, and dynamics. Neurocomputing. 2004;56:365–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2003.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hermans J. Hydrophilicity of cavities in proteins. Proteins Struct Func Genet. 1996;24:433–438. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199604)24:4<433::AID-PROT3>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 269 kb)