Abstract

Sensory neurone subtypes (≤ 25 μm apparent diameter) express a variety of Na+ channels, where expression is linked to action potential duration, and associated with differential IB4-lectin binding. We hypothesized that sensitivity to ATX-II might also discriminate neurones and report that 1 μm has negligible or small effects on action potentials in IB4 +ve, but dramatically increased action potential duration in IB4 −ve, neurones. The toxin did not act on tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-r) NaV1.8 currents; discrimination was based on tetrodotoxin-sensitive (TTX-s) Na+ channel expression. We also explored the effects of varying the holding potential on current threshold, and the effect of repetitive activation on action currents in IB4 +ve and −ve neurones. IB4 +ve neurones became more excitable with depolarization over the range −100 to −20 mV, but IB4 −ve neurones exhibited peak excitability near −55 mV, and were inexcitable at −20 mV. Eliciting action potentials at 2 Hz, we found that peak inward action current in IB4 +ve neurones was reduced, whereas changes in the current amplitude were negligible in most IB4 −ve neurones. Our findings are consistent with relatively toxin-insensitive channels including NaV1.7 being expressed in IB4 +ve neurones, whereas toxin sensitivity indicates that IB4 −ve neurones may express NaV1.1 or NaV1.2, or both. The retention of excitability at low membrane potentials, and the responses to repetitive stimulation are explained by the known preferential expression of NaV1.8 in IB4 +ve neurones, and the reduction in action current in IB4 +ve neurones with repetitive stimulation supports a novel hypothesis explaining the slowing of conduction velocity in C-fibres by the build-up of Na+ channel inactivation.

Introduction

The ability of primary sensory neurones to bind isolectin IB4 (IB4; from Griffonia simplicifolia) has been used for some time to discriminate between populations of primary sensory neurones (Silverman & Kruger, 1990), those that bind and those that do not bind the lectin being categorized as IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve, respectively. The lectin is known to bind to terminal carbohydrate residues on glycoprotein and glycolipid constituents within the cell membrane (e.g. Fullmer et al. 2004), whose presence has also been shown to be related to neuronal phenotype and growth factor receptor expression (Averill et al. 1995; Bennett et al. 1998; Priestley et al. 2002; Fang et al. 2006). In small neurones (< 25 μm in apparent diameter), IB4 binding is complementary to the synthesis of pro-inflammatory peptides, including calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). IB4 +ve neurones have therefore been classified as non-peptidergic, and IB4 −ve as peptidergic (Bennett et al. 1996; reviewed by McMahon, 1996). IB4 binding has been associated with neurones that generate wide action potentials and large transient tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-r) Na+ currents, attributable to NaV1.8 (Stucky & Lewin, 1999; Wu & Pan, 2004). In contrast, IB4 −ve small diameter neurones have action potentials of shorter duration and express NaV1.8 at lower densities. More recently, IB4 binding has been directly correlated with a polymodal nociceptor phenotype and NaV1.9 expression (Fang et al. 2006). The voltage-dependent K+ channel KV1.4 that generates an A-current is also expressed by the IB4 +ve subpopulation (Vydyanathan et al. 2005) and, taken together with the wide action potential, suggests that the ion channel complement of the IB4 +ve population must endow different functional properties to those found in IB4 −ve neurones. As the effect of membrane potential on IB4 +ve and −ve small diameter primary sensory neurones has not been systematically studied, we hypothesized that the relationship between membrane potential and excitability might differ between the IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve populations and also that undocumented pharmacological differences between IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones could exist.

ATX-II is a small polypeptide toxin (4.47 kDa) produced by the sea anemone Anemonia sulcata (e.g. Neumcke et al. 1980; reviewed by Wu & Narahashi, 1988), whose sting causes pain and inflammation. It has been extensively studied as a typical ligand at voltage-dependent Na+ channel neurotoxin binding-site III (e.g. Rogers et al. 1996). Toxin binding results in defective fast inactivation, and the induction of persistent Na+ currents. This is proposed to be through activation gate immobilization, where the toxin binding site is known to be at the extracellular loop end of the domain IV activation gate (Rogers et al. 1996; reviewed by Catterall et al. 2007), whose immobility with bound toxin does not prevent channel activation, but does inhibit the coupled inactivation process. This action may precipitate a part of the painful response to the toxin, as persistent Na+ currents are implicated in spontaneous or ectopic impulse generation. Evidence from heterologous expression studies has indicated that ATX-II has different binding affinities with human voltage-dependent Na+ channel subtypes (Oliveira et al. 2004; Wanke et al. 2009), suggesting the possibility that the toxin could be used to discriminate between subtypes expressed in neurones. We therefore studied the effects of ATX-II on IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neuronal populations, hypothesizing that if the Na+ channel complements were different in the two populations, ATX-II could potentially be used to discriminate between them.

One aspect of excitability that has been utilized to functionally identify individual C-fibres is the response to repetitive activation. Whereas A-fibres show a period of superexcitability immediately following an action potential (e.g. Raymond, 1979), resulting in increases in conduction velocity, C-fibres become sub-excitable and this sub-excitability manifests itself in increased impulse conduction times measured in animals and man (e.g. Gee et al. 1996; Serra et al. 1999). Furthermore the kinetics of the conduction time increase are dependent on fibre modality, and also on the frequency of repetitive activation. The mechanism of sub-excitability has been previously attributed to the activation of the electrogenic Na+ pump following Na+ ion influx (Rang & Ritchie, 1968), but recently, De Col et al. (2008) have suggested that this sub-excitability, at least in dural afferents, is caused by the accumulation of Na+ channel inactivation during a train of action potentials (potentially primarily involving the TTX-r Na+ channel NaV1.8). Increased inactivation would be expected to reduce the amplitude of action currents in the C-fibres, and thus slow impulse propagation. We have been able to test the effects of repetitive activation on action currents recorded in IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurone cell bodies in order to shed light on the mechanisms of conduction slowing.

Methods

Wistar rats weighing 50–150 g were killed by cervical dislocation, in accordance with UK Home Office guidelines (Schedule 1, Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986). Primary cultures of rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones were made on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips, as fully described elsewhere (e.g. Baker & Bostock, 1997; Foulkes et al. 2006). Briefly, the spine was removed and hemisected, dorsal root ganglia quickly isolated, washed in sterile Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (PAA, Yeovil, Somerset) and enzymatically dissociated (in Hepes-buffered saline containing 0.6 mg ml−1 collagenase type XI (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, UK) and protease type IX, 1 mg ml−1 (Sigma-Aldrich)). Neurones were plated out in serum and antibiotic supplemented DMEM, maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, and used for recording the following day.

Fluorescent IB4 live staining

Fluorescein-conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia IB4 (Vector Labs, Peterborough, UK) was made up as a 1 μg μl−1 solution in sterile water. Three microlitres was added to a 35 mm culture dish containing cultured neurones in 2 ml of extracellular recording solution. After a 15 min exposure in the dark, the culture was washed 3 times with clean extracellular solution before recording commenced. This allowed the discrimination of IB4 +ve and −ve neurone populations. Because IB4 +ve neurones were fluorescent to varying degrees, we confined ourselves to studying only the very brightest neurones, or conversely for IB4 −ve, those neurones without any staining. These latter IB4 −ve neurones were often found in close proximity to brightly stained neurones, and their lack of staining could not be attributed to an inadequate exposure to the lectin. Some of the neurones recorded from late in the project were visualized and photographed using a high-resolution digital camera (Nikon UK, Kingston upon Thames, UK; see Fig. 1).

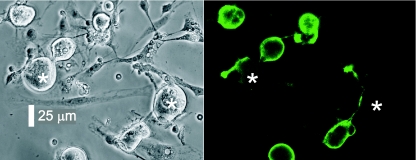

Figure 1. Phase-contrast photomicrograph of DRG neurones in culture and corresponding epifluorescence image.

Left-hand panel, DRG neurones in adherent culture, where IB4 −ve neurones are indicated by asterisks. Right-hand panel, IB4 +ve neurones fluoresce brightly with fluorescein-conjugated IB4, whereas the adjacent IB4 −ve neurones do not.

TTX and ATX-II

Tetrodotoxin was obtained from Alomone Labs (Botolph Claydon, UK), and applied to individual neurones acutely and locally at 250 nm using a gravity-fed system. Solutions containing both native and recombinant ATX-II (Alomone Labs) were applied in a similar manner without any noticeable differences in their activity. The anemone toxin was made up in extracellular recording solution with 0.01% bovine serum albumin.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made on dissociated neurones with an apparent diameter of < 25 μm. Electrodes were pulled from thin-walled glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus, Edenbridge, UK), and when introduced into the bath, the initial electrode resistance was no more than 2.5 MΩ. Recordings always began in voltage clamp, subsequently switching to current clamp once the series resistance and membrane capacitance had been estimated using the amplifer front panel potentiometers. Series resistance was always compensated by up to 70% in voltage clamp (with a nominal feedback lag of 12 μs in voltage clamp) and maintained subsequently in current clamp. Two different amplifiers were used to make current-clamp recordings. Axopatch 200B and 1D amplifiers (Molecular Devices, Union City, USA) were controlled using pCLAMP 9 and pCLAMP 10 (Molecular Devices), respectively. Voltage-clamp recordings were made using the Axopatch 200B only, and after achieving the whole-cell configuration in these experiments, a holding potential of −80 mV was used. The potential was stepped to a pre-pulse potential of −100 mV for 20 ms followed by an incrementing clamp step to evoke currents. Voltage-clamp current recordings were averaged from three consecutive families of sweeps and were leak subtracted on-line using a P/N protocol. Recordings were sampled at either 20 or 50 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 or 5 kHz (4-pole Bessel). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C).

For experiments where action current amplitudes were followed in current clamp, the current output of the amplifier was recorded simultaneously with the action potential. The action current flowing in the headstage, Iout, is reported to be proportional to the rate of rise of the action potential (Blair & Bean, 2002), and it had a peak value of around 10% or less of the total ionic current. The total ionic current was calculated off-line and given by −CmdV/dt, where Cm is the cell capacitance measured on initially going whole-cell in voltage clamp. Comparison of peak inward currents derived from action potentials differentiated with respect to time, and the current signal provided by the amplifier, gave similar responses to repetitive stimulation (cf. Figs 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Action current amplitude during 2 Hz suprathreshold stimulation in IB4 −ve and IB4 +ve neurones, and the effect of steady depolarization on the response in IB4 +ve neurones.

A and B, example recordings of Iout and −CmdV/dt (calculated off-line) for the IB4 −ve neurone generating the action potential in C. Lower panel in C indicates the stimulus current command waveform (Icommand). The superimposed traces in A, B and C indicate the first (grey trace) and fiftieth (black trace) sequentially recorded. Repetitive activation at 2 Hz had little effect on action current amplitude in most IB4 −ve neurones, A, B and D (only consistent data shown, the change was not significant assessed within the final 5 s, data plotted as means ±s.e.m.). IB4 +ve neurones showed a moderate suppression of peak action current (E) at a holding potential of −60 mV (at 24.5 s, P= 0.025, paired t test on raw data; P= 0.018, one-sample t test on the normalized data in the final 5 s, n= 8 data plotted as means ±s.e.m.). In addition, the action potential induction time increased (see Fig. 7). Holding at −50 mV appeared to enhance the normalized action current suppression over that found in the same neurones at −60 mV (F; at −50 mV, P < 0.001, one-sample t test on the normalized data in the final 5 s, n= 4), although the differences between the paired data collected at −60 and −50 mV were not found to be significant (data plotted as means ±s.e.m.)

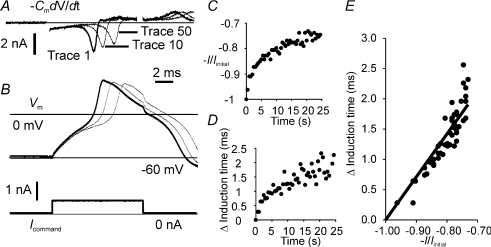

Figure 7. Action current amplitude and induction time during 2 Hz suprathreshold stimulation in an IB4 +ve neurone.

A, action currents (calculated off-line) and B, the corresponding action potential traces. Suprathreshold stimulus is indicated on the current command trace (B, lower panel). A and B show the first trace (heavy line) and tenth and fiftieth traces recorded during the stimulus train. C, action current amplitude is plotted normalized with respect to the current on the first trace. In D the change in the latency of the peak action current is plotted against time, and this change in induction time can also be clearly seen in the records presented in A and B. E, the relation between the change in induction time and action current was found to be approximately linear (constrained to Δinduction time = 0 where −I/Iinitial=−1), r2= 0.819, P < 0.0001.

Solutions

The solutions used for current-clamp recording were as follows. Extracellular quasi-physiological solution contained (in mm): 140 NaCl, 10 Hepes (hemi-Na), 2.1 CaCl2, 2.12 MgCl2, 2.5 KCl. Intracellular solution contained (in mm): 143 KCl, 3 EGTA-Na, 10 Hepes (hemi-Na), 1.21 CaCl2,1.21 MgCl2, 3 ATP (Mg), 0.5 GTP (Li). Solutions were buffered to 7.2–7.3 with the addition of small volumes of NaOH or HCl. Voltage-clamp solutions were as follows. Extracellular (in mm): 43.3 NaCl, 96.7 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), 10 Hepes, 2.1 CaCl2, 2.12 MgCl2, 0.5 4-aminopyridine, 7.5 KCl, 10 CsCl, 0.05 CdCl2, 0.25 × 10−3 tetrodotoxin (TTX). Intracellular (mm): 145 CsCl, 3 EGTA (Na), 10 Hepes, 1.21 CaCl2, 3 ATP (Mg), 0.5 GTP (Li) and 10 TEACl. These solutions were adjusted to be between pH 7.2 and 7.3 using CsOH.

Measurement of current threshold

The membrane potential was held constant at a chosen value by applying small holding currents that could be either hyperpolarizing or depolarizing. Current threshold was determined by applying a series of 10 ms current pulses using an incrementing command-step whose initial amplitude value and increment were controlled by the experimenter. The rate of current-pulse application during this process was 0.2 Hz. It was usual to apply one or two series of either six or eight current steps at each membrane potential, until the threshold was bracketed, and then to move onto the next value of membrane potential. In all experiments the membrane potential was held initially near −60 mV, and then hyperpolarized towards −100 mV, and then finally depolarized through −60 mV until membrane excitability was ultimately lost. The membrane potential was held at each chosen value for tens of seconds before beginning to ascertain the threshold. By rejecting recordings where hysteresis in the adequate current stimulus–membrane potential relation (at −60 mV) indicated changes in leakage, only stable recordings were analysed. For a 10 ms duration stimulus, a typical current increment was 20–40 pA, and current threshold was taken as the value that was just supra-threshold.

Derivation of near current threshold leakage current

At holding potentials of −60 mV and more negative, the input resistance of the preparation was determined using the curve-fitting facility in pCLAMP 10 to find the membrane time constant τ. τ is equal to RinCm, where Rin is the input resistance and Cm is the cell membrane capacity, the latter also independently estimated from cancelling the capacity transients when first going whole cell in voltage-clamp mode. Rin is therefore given by τ/Cm. In order to derive a near threshold leakage current, Ileak, an estimate of the membrane potential voltage change associated with a just-threshold stimulus (foot of action potential – holding potential (Vthresh)) was found for each holding potential by Ohm's law (Ileak=Vthesh/Rin), and then subtracted from the experimentally found current threshold, off-line. Applying this correction to some of our results allowed a better quantitative resolution of the relationship between current threshold and membrane potential, but did not affect our estimates of membrane potential of lowest threshold, nor the quality of the observed relationship between current threshold and membrane potential, as can be seen in Fig. 4.

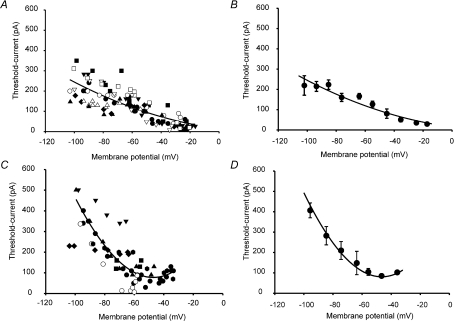

Figure 4. Current threshold measured in IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones changes with holding potential.

A shows the effect of changing membrane potential on the current threshold in IB4 +ve neurones. Individual neurones represented by different symbols. Where input resistance was < GΩ, leakage current was estimated and subtracted from the threshold current value (open symbols); where no correction was applied, the symbols are filled. Smooth curve in A and B is a square function drawn with best-fit parameters, of no theoretical significance. B shows the same data in 10 mV bins, plotting the mean data (x and y values) ±s.e.m. Some error bars smaller than symbol size. C and D are data collected from IB4 −ve neurones, treated in the same way as those from IB4 +ve neurones. Smooth curve in C and D is a cubic polynomial drawn with best-fit parameters and of no theoretical significance.

Measurement of half-width in the presence and absence of ATX-II

Action potential half-width was measured off-line in pCLAMP 9. It was defined as the length of time during an action potential spent at, or more depolarized than, the membrane potential value exactly halfway between the peak and the holding potential. For these experiments a 2 ms duration stimulus was used so that it terminated well before action potential repolarization.

Repetitive stimulation

Repetitive stimulation was carried out using a 10 ms duration stimulus at 2 or 0.5 Hz. Either the computer software trigger was used to initiate each stimulus, or a Neurolog (Digitimer) period generator attached to the A–D ‘start’ input. The stimulus current used was sufficient to elicit inward action current with a delay of around 5 ms, near mid-way through the applied stimulus, and this required the current to be substantially suprathreshold. The arrangement had two benefits. Firstly, every stimulus during the train had to excite an action potential, notwithstanding changes in membrane excitability, and secondly, action potential induction time increased throughout the train in IB4 +ve neurones, and the action current was most conveniently measured during the stimulus rather than at its offset.

Results

IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones distinguished by ATX-II

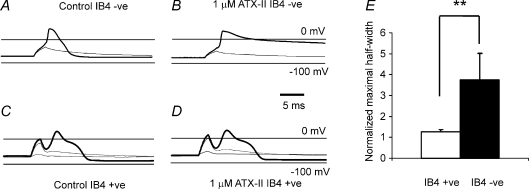

ATX-II brings about dramatic lengthening of action potentials in IB4 −ve neurones (Fig. 2), an effect expected following the inhibition of fast Na+ channel inactivation and prolongation of regenerative inward currents (Wang & Strichartz, 1985; Rogers et al. 1996). The response to the toxin is reminiscent of that to Leiurusα-toxin on action potentials recorded in nerve (e.g. Schmitt & Schmidt, 1972). However, the effect of 1 μm toxin is substantially less in IB4 +ve neurones (Fig. 2C and D), consistent with the two subsets of sensory neurones having Na+ channel complements discriminated by the toxin. A difference in transient TTX-s and TTX-r current (NaV1.8) density has already been reported for IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones (Wu & Pan, 2004), where IB4 +ve neurones generate TTX-r (NaV1.8) current that is larger than the TTX-s currents in the same neurones. In contrast, similarly sized IB4 −ve neurones generate larger TTX-s currents (Wu & Pan, 2004). In our experiments, exposure to ATX-II caused the average normalized action potential half-width (which includes every value recorded throughout the whole of the toxin exposure period), to become 1.08 ± 0.05 and 2.30 ± 0.61 × control values, for IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones, respectively (n= 8, 6; not significant and P < 0.028, respectively; Wilcoxon signed rank test). The substantially greater effect of the toxin on IB4 −ve neurones is more clearly revealed by comparing the normalized maximum action potential half-width recorded (Fig. 2E, P= 0.005 (Mann–Whitney U test)). Measurement of the longest half-widths obtained showed that there was an increase of over 30% in only one IB4 +ve neurone (where this neurone was exposed to the toxin for longer than 7.5 min), whereas all IB4 −ve neurones underwent increases greater than this (including those exposed for a shorter time). In one IB4 +ve neurone the change in action potential duration was under 20%, but 6 of the 8 neurones studied showed no convincing toxin-induced changes whatsoever. In IB4 −ve neurones, the mean action potential half-width increased from 4.81 ± 1.71 to 21.70 ± 14.07 ms with exposure to toxin. These findings indicate that the response to the toxin is greater in IB4 −ve than in IB4 +ve neurones, although the effects in IB4 −ve neurones do show substantial variability, in part brought about by unavoidably different toxin exposure times. (This is because we were unable to maintain the quality of the recording for each neurone for the same time, and lost some recordings before others while superfusing the toxin.) Even with constant washing for a minimum of 6 min following toxin application the action potential half-width remained persistently increased in IB4 −ve neurones (n= 4), and we suggest this finding is consistent with toxin affinity at low nanomolar concentrations.

Figure 2. The action of ATX-II on action potentials recorded in small diameter IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones.

Membrane potential responses to subthreshold (light traces) and suprathreshold (heavy traces) current stimuli, before (A and C) and after (B and D) superfusion of 1 μm ATX-II. Holding potential, −70 mV. In IB4 −ve, the action potential is dramatically prolonged, but toxin has negligible effects in IB4 +ve neurone. Neurones were stimulated with 2 ms-duration current pulses, where the just-suprathreshold stimulus current values in control were 2.4 nA and 600 pA, and whole-cell membrane capacitance 34 and 23 pF for IB4 −ve and IB4 +ve, respectively. The toxin can discriminate IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones (E) where the normalized maximal increase in half-width is 1.28 ± 0.10 versus 3.74 ± 1.27 (means ±s.e.m.) for IB4 +ve versus IB4 −ve neurones (n= 8, 6), P= 0.005 (Mann–Whitney U test).

NaV1.8 is insensitive to 1 μm ATX-II and discrimination depends on the characteristics of other Na+ channels

NaV1.8 can be conveniently isolated in voltage-clamp experiments, where other transient Na+ channels are blocked by the continuous presence of 250 nm external TTX. Figure 3A and B shows the effect of superfusing ATX-II on TTX-r Na+ currents that correspond to NaV1.8 in terms of voltage dependence and kinetics (cf. Akopian et al. 1999). The currents were unaffected by exposure to toxin, consistent with a report in the literature that NaV1.8 is also resistant to Leiurusα-toxin (Saab et al. 2002), that acts at the same site. In recordings from a neurone with a short duration action potential and likely to have been an IB4 −ve neurone (Fig. 3C and D), it can be seen that not only does ATX-II bring about a large change in action potential duration, but that voltage threshold also becomes more negative. The change in threshold is brought about by channels with an increased open probability operating within the most negative portion of their membrane potential activation range. It also indicates that the affected Na+ channels must be operating within a membrane potential range too negative for substantial NaV1.8 involvement. NaV1.8 is reported to be the major contributor to Na+ current in IB4 +ve neurones (the cell bodies of polymodal nociceptors, Fang et al. 2006). One reason ATX-II can discriminate between IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones is that there is proportionally higher NaV1.8 expression in IB4 +ve neurones. However, other evidence suggests that this is only a part of the answer. The TTX-s currents in IB4 +ve neurones must also be relatively resistant to ATX-II, as in most neurones tested no effect on action potential half-width was seen in response to toxin exposure.

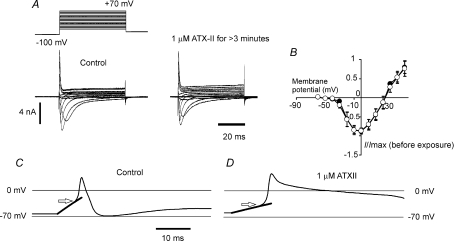

Figure 3. ATX-II acts on Na+ channels other than NaV1.8.

A, voltage-clamp families of TTX-r Na+ currents, corresponding to NaV1.8, recorded before and after exposure to 1 μm ATX-II (left- and right-hand panels, respectively). No removal of inactivation and concomitant increase in peak current was seen with the toxin. B, mean current–membrane potential plots where the maximal peak current amplitude evoked is plotted normalized with respect to the peak current recorded before exposure to toxin (100 nm), means ±s.e.m.n= 4. C, apparent voltage threshold in neurone with a narrow action potential was near −34.4 mV. The neurone was stimulated by a just-suprathreshold long-lasting depolarizing current. D, after toxin exposure (1 μm), apparent threshold value was close to −43.7 mV, consistent with toxin action on Na+ currents activating more negative than NaV1.8. Voltage-threshold value (near arrow) found by fitting an exponential to the sub-threshold component, and estimating the potential at which the change in membrane potential became non-passive.

IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones can be distinguished by the effect of membrane potential on current threshold

We chose to use a longer constant-current stimulus in order to estimate membrane current threshold (Fig. 4). Neurones were stimulated using a 10 ms-duration current pulse, although the membrane time constants, particularly in the best recordings (that had GΩ input resistances at negative holding potentials) were often very long and of a similar duration. In one experiment, we increased the stimulus duration to 20 ms and this had no effect on our measurement of current threshold, primarily because K+ channel activation modifies the passive response of the neurone to a depolarizing current and reduces the input resistance. Advantages of keeping the stimulus current duration constant are that it allowed a simple comparison of threshold over a wide membrane potential range, and also with values obtained in other neurones. However, the method may overestimate current threshold at more negative potentials where voltage-gated K+ channels are not activated and where NaV1.9 (when operating) may contribute to the depolarizing stimulus. Where input resistance was less than GΩ at negative holding potentials, we corrected the current threshold values by subtracting an estimate of the leakage current flowing through this resistance at the time of action potential induction, knowing the stimulus current-induced change in membrane potential (see Methods). Such corrections brought the current threshold values in line with those found in the best recordings (shifting the data points down the y-axis, open symbols in Fig. 4A and C). Corrected values appear to be completely consistent with our other results (and our findings on the membrane potential of lowest threshold are not different whether data were corrected or not).

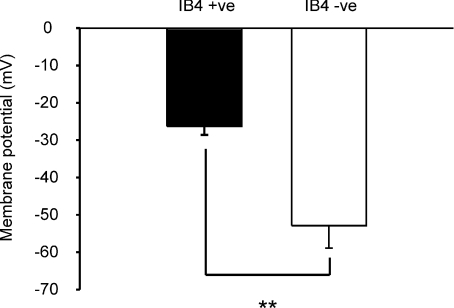

The relation between membrane potential and current threshold for IB4 +ve neurones appears flatter than that for IB4 −ve (compare Fig. 4B and D). IB4 −ve neurones exhibit a current threshold ‘U’ reminiscent of the threshold ‘U’ obtained by constant-current polarization of an A-fibre (Bostock & Grafe, 1985). An increase in current threshold at potentials more positive than that of the minimum value is likely to be caused by two mechanisms: Na+ channel inactivation, and increased membrane conductance through the activation of voltage-dependent K+ channels. The membrane potential of greatest excitability lies only 5–10 mV more depolarized than the normally accepted resting potential of −60 mV, suggesting that these neurones are tuned to respond most readily to the activation of receptor channels within a narrow membrane potential band close to the resting potential. On the other hand, IB4 +ve neurones become progressively more excitable with depolarization over a very wide membrane potential range, −100 to −20 mV, until (at even more positive membrane potentials) they cease to be excitable altogether because NaV1.8 inactivates. The membrane potentials of lowest current threshold are given in Fig. 5, and indicate that IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones are functionally different (P= 0.007, Student's t test). Another clear difference is that IB4 +ve neurones generate action potentials at membrane potentials more positive than those at which IB4 −ve neurones cease to be excitable, and a greater density of NaV1.8 expression in IB4 +ve neurones is likely to be the explanation for this.

Figure 5. Membrane potential with minimum current threshold is different in IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones.

Membrane potential value for each neurone (IB4 +ve, n= 8; IB4 −ve n= 5) is either the potential at which the current threshold was found to be a minimum, or less commonly (n= 3), the most positive value with one of two identical current threshold minima. Current threshold minimum for IB4 −ve neurones is close to 25 mV more negative than that for IB4 +ve (plotted as means ±s.e.m., P= 0.007, Student's t test).

Repetitive activation consistently suppresses action currents in IB4 +ve neurones

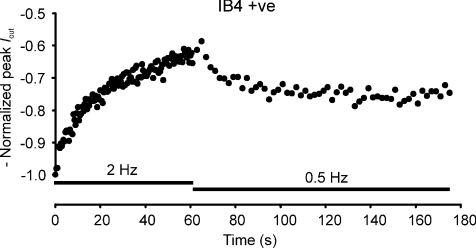

Repetitive activation slows conduction in C-fibres, but the mechanism of slowing has recently come under renewed scrutiny, with the new proposal by De Col et al. (2008) that it is brought about by the build-up of Na+ channel inactivation. We have used the current-clamped C-fibre cell body as a surrogate for the axon, where instead of conduction velocity, the amplitude of action currents, and the induction time (time to peak inward current) can be measured. The expectation would be that the disappearance of Na+ channels into inactivated states would gradually reduce the amplitude of the action current, and this is indeed what we found for IB4 +ve neurones stimulated at 2 Hz (Figs 6E and F, and 7). However, the change in action currents in most IB4 −ve neurones was small (Fig. 6A–D). In the current-clamped neurone the Na+ pump does not modify responses because the cell membrane can be held at a membrane potential of choice and the intracellular Na+ ion concentration is buffered by the electrode solution. Where the membrane potential was very stable in IB4 +ve neurones, the progressive reduction in action current was accompanied by a convincing increase in action potential induction time (Fig. 7). Induction time is most directly relatable to conduction velocity in C-fibres as the velocity depends upon local-circuit recruitment of sequential and neighbouring patches of axon membrane. These findings therefore support the De Col proposal. De Col et al. (2008) also discovered that the application of ouabain to dural afferents enhanced the relative (normalized) conduction velocity slowing caused by repetitive activation, the opposite of what would be expected if the slowing were brought about by the electrogenic activity of the Na+ pump. We have been able to partially mimic this effect of blocking the Na+ pump by applying a steady-state depolarization to the cell body (Fig. 6E), with the membrane potential being held at −50 mV, rather than −60 mV. We would expect this to enhance resting and activity-dependent build-up of inactivation, and the change in holding potential increases the suppression of action current. Activity-dependent inactivation does appear greater at −50 mV than at −60 mV, and the significant fall in action current seen at −50 mV (P < 0.001, one-sample t test) is a reflection of this. Such a reduction of action currents in axons could explain the enhanced conduction velocity slowing in dural afferents after Na+ pump blockade.

Lowering the stimulation rate in C-fibres immediately following a period of higher frequency activation has been shown to allow recovery in conduction velocity. For example, De Col et al. (2008) used a switch from 2 Hz to 0.5 Hz, that gave rise to partial recovery towards the initial conduction velocity measured after a period of inactivity. We have used a similar protocol (Fig. 8) where partial recovery of action currents occurs in an IB4 +ve neurone, in a manner quite similar to that found for recovery of conduction velocity, and consistent with changes in Na+ channel availability being the underlying cause of latency changes in C-fibres.

Figure 8. Action current amplitude is stimulation frequency dependent.

−Normalized peak Iout for an IB4 +ve neurone subjected to 2 Hz stimulation, subsequently reduced to 0.5 Hz after 1 min, and showing some recovery in action current amplitude at the lower stimulus frequency.

Discussion

Na+ channel subtypes operating in IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones

Primary sensory neurones express a variety of Na+ channel subtypes (e.g. Black et al. 1996; Akopian et al. 1996; Sangameswaran et al. 1996; Cummins et al. 1999; reviewed by Baker & Wood, 2001). ATX-II has already been screened for activity against heterologously expressed human Na+ channels (Oliveira et al. 2004; Wanke et al. 2009), and it exerts effects in a channel subtype-specific way. The toxin sensitivity is chiefly dependent upon the amino acid sequence at the outer end of segment 3, domain IV, and the adjacent residues in the S3–S4 loop. Sequence alignment indicates that the rat channels NaV1.1 and 1.2 are the same as the human in this region. NaV1.1 and NaV1.2 are much the most sensitive channels, with an apparent EC50 within the single nanomolar range. Rat NaV1.6 has the same sequence as the human channel, with an expected EC50 near 240 nm. Rat NaV1.7 has the same sequence as human NaV1.3 in this region, and this is associated with a sensitivity within the micromolar range. We have also heterologously expressed human NaV1.7, and were unable to detect any activity of ATX-II at concentrations up to 1 μm on the currents in voltage clamp (M.D. Baker, unpublished observations). Furthermore, we have shown that rat NaV1.8 is not noticeably sensitive to the toxin at 1 μm. These differences in toxin sensitivity could therefore be consistent with NaV1.1 and/or 1.2 comprising the bulk of the TTX-s current in IB4 −ve neurones, where a near 7 nm EC50 would explain why the toxin has such a dramatic effect on action potential half-width, and as NaV1.1 transcripts are not downregulated with nociceptor ablation (Abrahamsen et al. 2008, see below) this may favour the involvement of NaV1.2. However, these considerations do not rule out a minor involvement of other toxin-insensitive channels as well. Our data indicate that the TTX-s current in IB4 +ve neurones appears much less sensitive to toxin, and the currents are therefore likely to be generated by NaV1.7 and perhaps NaV1.6 that have a reported EC50 value within the micromolar range and 240 nm, respectively (Oliveira et al. 2004; Wanke et al. 2009), in the possible absence of NaV1.1 and 1.2. NaV1.7 is known to play an important role in human pain states through studies of mutations causing gain of function (Cummins et al. 2004; Fertleman et al. 2006) and loss of function (Cox et al. 2006) and is therefore of particular interest. Our findings provide an insight into the channel function in sensory neuronal subtypes, associating it most firmly with IB4 +ve neurones. Furthermore, in the global, conditional diphtheria toxin A (floxed)-expressing mice when crossed with NaV1.8-Cre mice (Abrahamsen et al. 2008), all IB4 +ve neurones die in the Cre-expressing offspring. With the loss of NaV1.8-expressing neurones, NaV1.7 transcripts in DRG are substantially reduced, consistent with expression of NaV1.7 in IB4 +ve neurones.

Although a complete description of the expression and distribution of Na+ channel subtypes in small diameter Peripheral nervous system (PNS) axons is not yet available, there is excellent direct functional evidence for the expression of NaV1.8 in the endings of small diameter afferents (e.g. Strassman & Raymond, 1999; Zimmermann et al. 2007; Carr et al. 2009). Also, while functional evidence for NaV1.7 expression in small diameter afferents is more circumstantial, behavioural evidence from nociceptor-specific knock-out mice (Nassar et al. 2004) and the effects of channel mis-sense mutations in man (Cummins et al. 2004; Fertleman et al. 2006; Cox et al. 2006), strongly imply that NaV1.7 is also expressed in afferent nerve fibres. Finally, in the CNS, immunohistochemical evidence reveals a preferential expression of NaV1.2 in unmyelinated nerve fibres (Westenbroek et al. 1989, 1992).

The excitability ‘U’ and its relation to small diameter sensory neurones

Incrementally increasing steady-state hyperpolarization increases the difference between the voltage threshold for action potential induction and the membrane potential, so that a progressively larger current stimulus is required to activate an axon. In contrast, incrementally increasing steady-state depolarization from rest first makes the axon more excitable, by reducing the difference between membrane potential and voltage threshold, but with sufficient depolarization the decreasing availability of Na+ channels reduces excitability, because of increasing channel inactivation. These factors give rise to the excitability ‘U’ previously described by Bostock & Grafe (1985) as a ‘U’-shaped current threshold versus membrane polarization profile for A-fibre nodes of Ranvier. The region of the relation with a positive slope indicates the range of membrane potentials in which a switch in the mechanism of accommodation occurs, from one dependent on the activation of potassium channels (where membrane potential is high), to one dependent on Na+ channel inactivation (where the membrane potential is low) (Baker & Bostock, 1989). Small diameter sensory neurones might be expected to differ from A-fibre nodes of Ranvier because of the diversity of their Na+ channels, and this is particularly true of IB4 +ve neurones known to generate the most substantial NaV1.8 current. IB4 −ve neurones, on the other hand, have briefer action potentials (Stucky & Lewin, 1999; Wu & Pan, 2004) as a result of expressing functionally more homogeneous Na+ channels. They have a significantly more hyperpolarized minimum current threshold, and thus behave most like nodes of Ranvier.

The presence of NaV1.8 not only gives rise to longer action potentials in IB4 +ve neurones, but explains why they remain excitable at membrane potentials as depolarized as −20 mV (Fig. 4). It is now understood that nerve endings incorporating NaV1.8 are able to generate action potentials even when very depolarized (for example to −30 mV; Carr et al. 2002, 2009; cf. Zimmermann et al. 2007), and that this is a part of the physiological function of these channels. Hypothetically, where nerve ending membrane potential can be reduced by intense cooling, for example (cf. Reid & Flonta, 2001; Zimmermann et al. 2007), endings that normally do not express enough NaV1.8 might cease to function altogether. From our present results we would predict that neurones releasing pro-inflammatory peptides could be preferentially affected by such a mechanism.

Repetitive activation

The response of action currents to repetitive activation also provides an insight into the molecular subtypes of Na+ channel involved in conferring excitability on IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones. This is because evidence has indicated that particular Na+ channel subtypes are especially prone to undergoing a build-up of inactivation in response to prolonged or repeated depolarizations. NaV1.8 is the primary example (Blair & Bean, 2003). NaV1.8 has been reported to be able to generate a major portion of the inward action current in small DRG neurones during the action potential upswing (Blair & Bean, 2002), or also to enter a slow-inactivated state after prolonged or substantial depolarization (e.g. to +40 mV; Blair & Bean, 2003) and with a 1 Hz application of an action potential waveform-shaped command pulse. This property was suggested by De Col et al. (2008) to be the reason for conduction slowing in dural afferents. Whether the apparent differences in action current amplitude suppression with repeated activation between IB4 +ve and IB4 −ve neurones are related to differences in the density of channel expression only between the two chemically discriminated cell types, or whether they are due to a combination of relative current density and differences in slow inactivation kinetics (Choi et al. 2007), is yet to be determined. However, these considerations do not completely rule-out a possible contribution from TTX-sensitive Na+ channels to the phenomenon. For example, NaV1.7 heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells undergoes slow inactivation with a mid-point near to −50 mV, when investigated with 30 s conditioning pulses (Cummins et al. 2004). In addition, NaV1.7-r, a TTX-resistant mutant of NaV1.7, has been heterologously expressed in NaV1.8 knock-out neurones (Herzog et al. 2003). The channel is reported to exhibit a slow return to operability at normal resting potentials (called ‘repriming’) following depolarizing conditioning pulses. A time constant of 40 ms for escape of NaV1.7-r from inactivation at −60 mV is substantially greater than values reported for NaV1.6-r, and at −80 mV the value reported for NaV1.7-r is nearer 80 ms, and therefore if these estimates are accurate the channel might also contribute to the build-up of Na+ channel inactivation with repetitive stimulation.

Many IB4 −ve neurones do not show any substantial change in action currents with repetitive activation at 2 Hz, so overall, small neurones in culture are heterogeneous in their responses, just as the conduction velocity slowing in small afferents appears heterogeneous (e.g. Gee et al. 1996; Serra et al. 1999). We suggest that this variability in conduction velocity slowing might now be at least partly attributed to differences in Na+ channel subtype expression in axons. Finally, it remains possible that in some IB4 −ve small diameter afferents, not examined by De Col et al. (2008), the activity of the Na+ pump may indeed be responsible for activity-dependent reductions in conduction velocity.

Acknowledgments

J.F.P. and A.S. were members of the intercalated Neuroscience degree course at Barts and the London School of Medicine. This work was supported in part by a Royal Society Research Grant and the University of London Central Research Fund.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ATX-II

Anemonia sulcata polypeptide toxin II

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- IB4

Griffonia simplicifolia isolectin IB4

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

Author contributions

A.S. and J.F.P. collected, analysed and interpreted data. M.D.B. conceived the experiments, collected, analysed and interpreted data, and drafted the article.

References

- Abrahamsen B, Zhao J, Asante CO, Cendan CM, Marsh S, Martinez-Barbera JP, Nassar MA, Dickenson AH, Wood JN. The cell and molecular basis of mechanical, cold, and inflammatory pain. Science. 2008;321:702–705. doi: 10.1126/science.1156916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Wood JN. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel expressed by sensory neurons. Nature. 1996;379:257–262. doi: 10.1038/379257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian AN, Souslova V, England S, Okuse K, Ogata N, Ure J, Smith A, Kerr BJ, McMahon SB, Boyce S, Hill R, Stanfa LC, Dickenson AH, Wood JN. The tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel SNS has a specialized function in pain pathways. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:541–548. doi: 10.1038/9195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill S, McMahon SB, Clary DO, Reichardt LF, Priestley JV. Immunocytochemical localization of trkA receptors in chemically identified subgroups of adult rat sensory neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1484–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Bostock H. Depolarization changes the mechanism of accommodation in rat and human motor axons. J Physiol. 1989;411:545–561. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MD, Bostock H. Low-threshold, persistent sodium current in rat large dorsal root ganglion neurons in culture. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1503–1513. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MD, Wood JN. Involvement of Na+ channels in pain pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DL, Dmietrieva N, Priestley JV, Clary D, McMahon SB. trkA, CGRP and IB4 expression in retrogradely labelled cutaneous and visceral primary sensory neurones in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1996;206:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DL, Michael GJ, Ramachandran N, Munson JB, Averill S, Yan Q, McMahon SB, Priestley JV. A distinct subgroup of small DRG cells express GDNF receptor components and GDNF is protective for these neurons after nerve injury. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3059–3072. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03059.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JA, Dib-Hajj S, McNabola K, Jeste S, Rizzo MA, Kocsis JD, Waxman SG. Spinal sensory neurons express multiple sodium channel alpha-subunit mRNAs. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;43:117–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ current, TTX-resistant Na+ current and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10277–10290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10277.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Role of tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current slow inactivation in adaptation of action potential firing in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10338–10350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock H, Grafe P. Activity-dependent excitability changes in normal and demyelinated rat spinal root axons. J Physiol. 1985;365:239–257. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RW, Pianova S, Brock JA. The effects of polarizing current on nerve terminal impulses recorded from polymodal and cold receptors in the guinea-pig cornea. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:395–405. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RW, Pianova S, McKemy DD, Brock JA. Action potential initiation in the peripheral terminals of cold-sensitive neurones innervating the guinea-pig cornea. J Physiol. 2009;587:1249–1264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Cestèle S, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, Scheuer T. Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon. 2007;49:124–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Differential slow inactivation and use-dependent inhibition of NaV1.8 channels contribute to distinct firing properties in IB4+ and IB4– DRG neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1258–1265. doi: 10.1152/jn.01033.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JJ, Reimann F, Nicholas AK, Thornton G, Roberts E, Springell K, Karbani G, Jafri H, Mannan J, Raashid Y, Al-Gazali L, Hamamy H, Valente EM, Gorman S, Williams R, McHale DP, Wood JN, Gribble FM, Woods CG. An SCN9A channelopathy causes congenital inability to experience pain. Nature. 2006;444:894–898. doi: 10.1038/nature05413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Akopian AN, Wood JN, Waxman SG. A novel persistent tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium current in SNS-null and wild-type small primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-j0001.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Electrophysiological properties of mutant NaV1.7 sodium channels in a painful inherited neuropathy. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8232–8236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2695-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Col R, Messlinger K, Carr RW. Conduction velocity is regulated by sodium channel inactivation in unmyelinated axons innervating the rat cranial meninges. J Physiol. 2008;586:1089–1103. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Djouhri L, McMullan S, Berry C, Waxman SG, Okuse K, Lawson SN. Intense isolectin-B4 binding in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons distinguishes C-fibre nociceptors with broad action potentials and high NaV1.9 expression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7281–7292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1072-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertleman CR, Baker MD, Parker KA, Moffatt S, Elmslie FV, Abrahamsen B, Ostman J, Klugbauer N, Wood JN, Gardiner RM, Rees M. SCN9A mutations in paroxysmal extreme pain disorder: allelic variants underlie distinct channel defects and phenotypes. Neuron. 2006;52:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes T, Nassar MA, Lane T, Matthews EA, Baker MD, Gerke V, Okuse K, Dickenson AH, Wood JN. Deletion of annexin 2 light chain p11 in nociceptors causes deficits in somatosensory coding and pain behaviour. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10499–10507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1997-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullmer JM, Riedl MS, Higgins L, Elde R. Identification of some lectin IB4 binding proteins in rat dorsal root ganglia. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1705–1709. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000136037.54095.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee MD, Lynn B, Cotsell B. Activity-dependent slowing of conduction velocity provides a method for identifying different functional classes of C-fibre in the rat saphenous nerve. Neuroscience. 1996;73:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog RI, Cummins TR, Ghassemi F, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Distinct repriming and closed-state inactivation kinetics of NaV1.6 and NaV1.7 sodium channels in mouse spinal sensory neurons. J Physiol. 2003;551:741–750. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SB. NGF as a mediator of inflammatory pain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:431–440. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar MA, Stirling LC, Forlani G, Baker MD, Matthews EA, Dickenson AH, Wood JN. Nociceptor-specific gene deletion reveals a major role for NaV1.7 (PN1) in acute and inflammatory pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12706–12711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404915101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumcke B, Schwarz W, Stämpfli R. Modification of sodium inactivation in myelinated nerve by Anemonia toxin II and iodate. Analysis of current fluctuations and current relaxations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;600:456–466. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JS, Redaelli E, Zaharenko AJ, Cassulini RR, Konno K, Pimenta DC, Freitas JC, Clare JJ, Wanke E. Binding specificity of sea anemone toxins to NaV1.1–1.6 sodium channels: unexpected contributions from differences in the IV/S3-S4 outer loop. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33323–33335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley JV, Michael GJ, Averill S, Liu M, Willmott N. Regulation of nociceptive neurons by nerve growth factor and glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:495–505. doi: 10.1139/y02-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP, Ritchie JM. On the electrogenic sodium pump in mammalian non-myelinated nerve fibres and its activation by various external cations. J Physiol. 1968;196:183–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond SA. Effects of nerve impulses on threshold of frog sciatic nerve fibres. J Physiol. 1979;290:273–303. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Flonta M-L. Cold transduction by inhibition of a background potassium conductance in rat primary sensory neurones. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JC, Qu Y, Tanada TN, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of high affinity binding ofα-scorpion toxin and sea anemone toxin in the S3-S4 extracellular loop in domain IV of the Na+ channel α subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15950–15962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab CY, Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Molecular determinant of NaV1.8 sodium channel resistance to the venom from the scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;331:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangameswaran L, Delgado SG, Fish LM, Koch BD, Jakeman LB, Stewart GR, Sze P, Hunter JC, Eglen RM, Herman RC. Structure and function of a novel voltage-gated, tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel specific to sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5953–5956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.5953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt O, Schmidt H. Influence of calcium ions on the ionic currents of nodes of Ranvier treated with scorpion venom. Pflugers Arch. 1972;333:51–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00586041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra J, Campero M, Ochoa J, Bostock H. Activity-dependent slowing of conduction differentiates functional subtypes of C fibres innervating human skin. J Physiol. 1999;515:799–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.799ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JD, Kruger L. Selective neuronal glycoconjugate expression in sensory and autonomic ganglia: relation of lectin reactivity to peptide and enzyme markers. J Neurocytol. 1990;19:789–801. doi: 10.1007/BF01188046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassman AM, Raymond SA. Electrophysiological evidence for tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels in slowly conducting dural sensory fibres. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:413–424. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky CL, Lewin GR. Isolectin B4-positive and -negative nociceptors are functionally distinct. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6497–6505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06497.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vydyanathan A, Wu ZZ, Chen SR, Pan HL. A-type voltage-gated K+ currents influence firing properties of isolectin B4-positive but not isolectin B4-negative primary sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:3401–3409. doi: 10.1152/jn.01267.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GK, Strichartz G. Kinetic analysis of the action of Leiurus scorpion α-toxin on ionic currents in myelinated nerve. J Gen Physiol. 1985;86:739–762. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.5.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanke E, Zaharenko AJ, Redaelli E, Schiavon E. Actions of sea anemone type 1 neurotoxins on voltage-gated sodium channel isoforms. Toxicon. 2009;54:1102–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Merrick DK, Catterall WA. Differential subcellular localization of the RI and RII Na+ channel subtypes in central neurons. Neuron. 1989;3:695–704. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Noebels JL, Catterall WA. Elevated expression of type II Na+ channels in hypomyelinated axons of shiverer mouse brain. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2259–2267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02259.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Narahashi T. Mechanism of action of novel marine neurotoxins on ion channels. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1988;28:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.28.040188.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZZ, Pan HL. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive and -resistant Na+ channel currents in subsets of small sensory neurons of rats. Brain Res. 2004;1029:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann K, Leffler A, Babes A, Cendan CM, Carr RW, Kobayashi J, Nau C, Wood JN, Reeh PW. Sensory neuron sodium channel NaV1.8 is essential for pain at low temperatures. Nature. 2007;447:855–858. doi: 10.1038/nature05880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]