Summary

Background

Platelet production is an intricate process that is poorly understood. Recently, we demonstrated that the natural PPARγ ligand, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), augments platelet production from megakaryocytes. 15d-PGJ2 can exert effects independent of PPARγ, by increasing oxidative stress. Herein, we reveal 15d-PGJ2 affects platelet production by inducing heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1).

Objectives

To further investigate the influence of 15d-PGJ2 on megakaryocytes and to understand the role of HO-1 in platelet production.

Methods

Meg-01 cells (a primary megakaryoblastic cell line) and primary human megakaryocytes derived from cord blood were used to examine the effects of 15d-PGJ2 on HO-1 expression in megakaryocytes and their daughter platelets. The role of HO-1 activity in thrombopoiesis was studied in vitro using established models of platelet production.

Results and conclusions

15d-PGJ2 potently induced HO-1 mRNA and protein expression in Meg-01 cells and primary human megakaryocytes. The platelets produced from these megakaryocytes also expressed elevated levels of HO-1. 15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1 was independent of PPARγ, but could be replicated using other electrophilic prostaglandins, suggesting that the electrophilic properties of 15d-PGJ2 were important for HO-1 induction. Interestingly, inhibiting HO-1 activity enhanced 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production and reactive oxygen species generation. These new findings support the concept that HO-1 activity is inhibitory for platelet production.

Introduction

Thrombopoiesis is poorly understood, but is of great interest because adequate platelet numbers are necessary for hemostasis. We previously reported that 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) enhances platelet production from megakaryocytes (ref blood paper). 15d-PGJ2 is a potent natural peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) ligand that is formed spontaneously from prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) (1, 2). PPARγ is a member of the nuclear hormone superfamily that heterodimerizes with the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR) to induce the expression of genes important for lipid and glucose metabolism, as well as inflammation (3). We recently demonstrated that PPARγ is expressed in megakaryocytes and platelets (4). Importantly, treatment of platelets with PPARγ ligands such as 15d-PGJ2 attenuated platelet activation (4). In addition, PPARγ ligands can also induce heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)(5, 6).

Heme oxygenases (HO) are believed to protect against the toxicity of free heme by catalyzing the oxidation of heme to ferrous iron, carbon monoxide (CO) and biliverdin. Biliverdin is then converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase. While HO-2 is constitutive, HO-1 is induced by diverse stimuli, especially those that induce reactive oxygen species (ROS), including cigarette smoke, oxidized lipids, and metalloporphyrins (7). While the physiologic importance of HO-1 in platelet production has never been described, the clinical manifestation of thrombocytosis in a patient with HO-1 deficiency suggests that HO-1 dampens thrombopoiesis (8, 9). We therefore hypothesized that 15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1 would regulate thrombopoiesis. Here, we demonstrate that 15d-PGJ2 induced HO-1 in Meg-01 cells and in primary human megakaryocytes, and inhibition of HO-1 activity enhanced 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production. These new data suggest that HO-1 plays an inhibitory role in thrombopoiesis.

Materials and methods

Reagents

15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone were obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA); Pioglitazone was obtained from ChemPacific (Baltimore, MD); 9, 10 dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (CAY10410), PGJ2, PGD2, 15d-PGD2 and GW9662 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); anti-HO-1 (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI); hemin, N- acetylcysteine (NAC), and glutathione reduced ethyl ester (GSH-EE) were all purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); and total actin (CP-01) was obtained from Oncogene (Cambridge, MA). 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Cells and culture conditions

Meg-01 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid; Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 4.5g/L glucose (Invitrogen), and 50 μg/mL gentamicin (Invitrogen).

Human blood platelet isolation

Whole blood was obtained under University of Rochester IRB approval from male and female donors by venipuncture into a citrate phosphate dextrose adenine solution containing collection bag (Baxter Fenwal, Round Lake, IL) or Vacutainer tubes containing buffered citrate sodium (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Platelets were then isolated as described (4, 10). On average, 5.5×1010 platelets/unit of blood were obtained, and the platelet purity was greater than 99%.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with Caltag Laboratories fixation medium A (Invitrogen) for 15 min, followed by an incubation with the HO-1 antibody (1:1000) (diluted in Caltag Laboratories permeabilization medium B (Invitrogen)) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Cells were then washed and incubated with a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA) (1:400 dilution in Reagent B) for 1 h at RT. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry or were air-dried on slides and coverslipped in Vectashield Hard Set Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories Inc, Burlingame, CA). Cells were visualized using an Olympus BX51 light microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY), photographed with a SPOT camera and analyzed with SPOT RT software (New Hyde Park, NY).

Construction of a lentiviral vector expressing PPARγ siRNA

A lentiviral construct expressing PPARγ siRNA was developed as previously described (ref. Blood paper). Briefly, a PPARγ siRNA target sequence was cloned downstream of the RNA polymerase III U6 promoter and subcloned into a FG12 lentiviral vector which expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the Ubiquitin C promoter. HEK 293 cells expressing this siRNA PPARγ had reduced PPARγ protein levels (>90%, data not shown). To make the lentivirus, HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with 3 plasmids: the envelope vector (CMV-VSVG), the transfer vector (FG12-shRNAPPAR), and the packaging construct (pCMVΔ89.2 (gag/pol proteins)). Viral supernatants were collected every 8 h for 2 days and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 50,000 ×g for 2 h at 4°C using a Beckman SW 28 rotor. Viral titers were determined by infection of HeLa cells with serial dilutions of the viral stocks. Meg-01 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20. After 48 h, approximately 56% of the PPARγ siRNA cells were transduced as determined by flow cytometry. The GFP positive (+) cells were then sorted by FACS and grown in RPMI with 5% FBS.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared using ELB buffer (15mM HEPES (pH 7), 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM NA3VO4, 50 μM ZnCl2, supplemented with 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, and mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and protein was quantified using bicinchoninic acid protein assay (BCA assay kit) (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Twenty micrograms of protein was electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, electroblotted onto Immun-blot PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and blocked with 10% nonfat dry milk in 0.1% Tween 20 (in PBS) for 1 h at RT. Antibodies against HO-1 (1:5000) (Assay Designs), PPARγ (1:1000) (Biomol) and actin (1:10,000) were used to assess changes in protein levels. Membranes were washed and then incubated with an appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The membranes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) and developed on Classic x-ray film (Laboratory Product Sales, Rochester, NY).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the cells by using the RNeasy RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA and HO-1 mRNA quantified using the following primers (11, 12): HO-1: 5′-CAGGCAGAGAATGCTGAGTCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTTCACATAGCGCTGCA-3′ (antisense). Human 7S sequences were used as a control. 7S: 5′-ACCACCAGGTTGCCTAAGGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CACGGGAGTTTTGACCTGCT-3′ (antisense). iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used in the real-time PCR assay and results were analyzed with Bio-Rad iCycler software. Values were normalized to 7S and fold-change compared between untreated and 15d-PGJ2-treated Meg-01 cells.

Platelet isolation for Western blot

Ten ×106 Meg-01 cells or primary human megakaryocytes were untreated or treated with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM). After 24 h, platelets were isolated by centrifugation at 150 ×g for 10 min. Supernatants underwent sequential centrifugation (500 ×g for 10 min and 1000 ×g for 10 min). Platelet purity (>99%) was assessed by flow cytometry. The platelet pellet was lysed and western blot was performed as described above.

HO-1 activity assay

Meg-01 cells (1×107) were pretreated with SnPPIX (5μM) for 1 h and then treated with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 12 h. HO-1 activity was measured as previously described (13). Briefly, Meg-01 lysates were added to a reaction mixture containing hemin as a substrate, mouse liver cytosol as a source of biliverdin reductase and NADPH. The reaction was carried out at 37°C in the dark and terminated by the addition of 1 mL of chloroform to extract bilirubin, a product of HO degradation. The concentration of bilirubin was determined spectrophotometrically, using the difference in absorbance between 460 and 530 nm with an absorption coefficient of 40 mM−1 cm−1.

Platelet production analysis

Cells were pretreated with SnPPIX (5 μM) and/or GSH-EE (5 mM) or NAC (1 mM) for 1-2 h, followed by treatment with either vehicle, hemin (1 μM), or 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 24 h. Platelets were then isolated and quantified as previously described (ref. Blood paper). Briefly, platelets underwent centrifugation at 150 ×g for 10 min and the supernatants underwent sequential centrifugation (500 ×g for 10 min and 1000 ×g for 10 min). The remaining platelet pellet was fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with a CD61 or CD41 antibody. 7-AAD (BD Pharmingen) was added for 10 min before analyzing the cells by flow cytometry. Platelets were identified using well-described parameters (14-17): size (using normal human platelets as a control), presence of CD61 or CD41 and lack of DNA as determined by the absence of 7-AAD staining. Ten thousand platelet events were collected and platelets were quantified by rate (platelet events/second) (18).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

Cells were pretreated with SnPPIX (5 μM) for 1-2 h. Cells were then treated with either vehicle, hemin (1 μM), or 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 6 h. ROS production was measured by adding carboxy-H2DCFDA (10 μM) to cells for 20 min at RT. The cells were washed and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Megakaryocyte differentiation from human cord blood-derived CD34+ cells

Human CD34+ cord blood cells were obtained from AllCells (Emeryville, CA). Cells were plated at 2.5×105 cells per well in a 12-well plate and cultured in serum-free medium as previously described (19) and supplemented with 100 ng/mL of recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). After 14 days in culture, megakaryocytes were identified by staining with a CD61-FITC antibody and analyzed on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by paired two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) All data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation and statistical significance was assigned for P<0.05.

Results

15d-PGJ2 upregulates HO-1 in Meg-01 cells

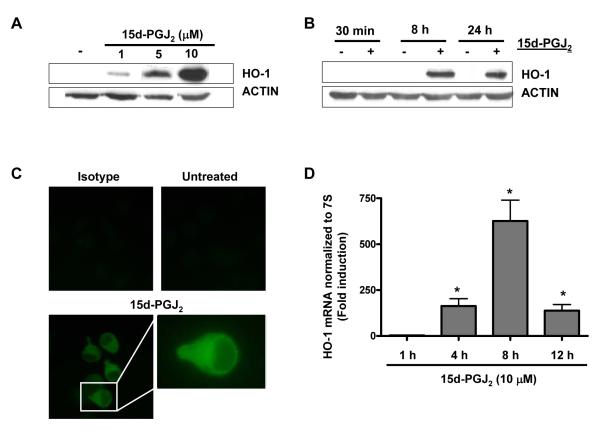

We first tested whether 15d-PGJ2 would influence HO-1 protein expression in Meg-01 cells. Treatment with 15d-PGJ2 strongly upregulated HO-1 protein in a dose-dependent (1-10 μM) manner in Meg-01 cells (Fig. 1A). Meg-01 cells treated with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 30 min, 8 h or 24 h show an induction of HO-1 protein at both 8 h and 24 h (Fig. 1B). These findings were verified by immunofluorescence. Figure 1C demonstrates that treatment with 10 μM of 15d-PGJ2 induced HO-1 protein expression predominantly in the cytoplasm.

Fig. 1.

15d-PGJ2 upregulates HO-1 in Meg-01 cells. A) Western blot analysis of HO-1 in Meg-01 cell lysates after incubation for 24 h with increasing concentrations of 15d-PGJ2. B) Western blot analysis of HO-1 in Meg-01 cell lysates after incubation with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 30 min, 8 h, and 24 h. C) Immunofluorescent microscopy of HO-1 expression in Meg-01 cells after incubation with 15d-PGJ2 for 24 h. D) Real-time PCR of HO-1 mRNA expression after incubation with 15d-PGJ2 for 1 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 12 h. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05).

Finally, we examined HO-1 steady-state mRNA levels after 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) treatment. Analysis of HO-1 mRNA by real-time PCR showed a >200-fold induction of HO-1 mRNA by 4 h (Fig. 1D), which peaked by 8 h (>700-fold) and remained significantly above control (untreated) levels by 12 h (>200-fold).

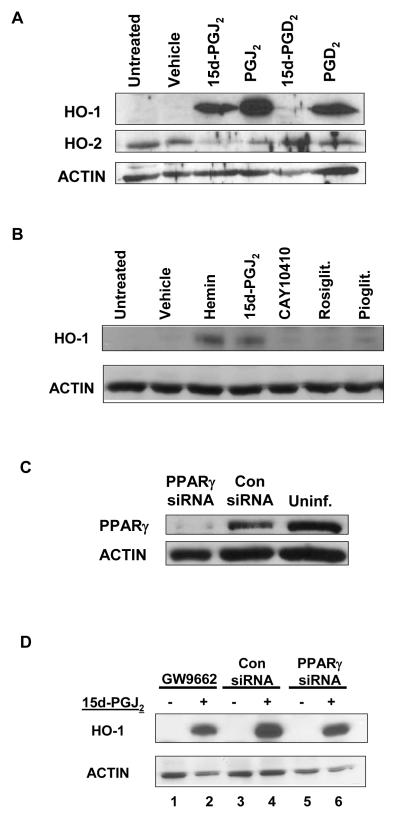

HO-1 upregulation by 15d-PGJ2 is independent of PPARγ

15d-PGJ2 is a metabolite of PGD2. We next evaluated the ability of PGD2 and two other metabolites, PGJ2 and 15d-PGD2 (20), to enhance HO-1 expression. Figure 2A demonstrates that PGD2, PGJ2, and 15d-PGJ2 all induced HO-1 protein expression in Meg-01 cells. Interestingly, 15d-PGD2 failed to induce HO-1 protein expression. HO-2 expression remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 2.

HO-1 upregulation by 15d-PGJ2 is independent of PPARγ. A) Meg-01 cells were treated with 10 μM of 15d-PGJ2, PGJ2, 15d-PGD2, or PGD2 for 24 h. HO-1 and HO-2 protein expression was analyzed by western blot. B) Meg-01 cells were treated with hemin (1 μM), 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM), 9,10 dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (CAY10410)(10 μM), rosiglitazone (rosiglit.) (10 μM), pioglitazone (pioglit.) (10 μM) for 24 h. HO-1 expression was analyzed by western blot. C) Western blot showing that cells infected with a lentiviral vector expressing PPARγ-siRNA have ~90% less protein compared with cells infected with the control (con) virus. D) Meg-01 cells were treated with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) for 24 h following a 1 h pretreatment with the small molecule PPARγ irreversible antagonist, GW9662. Meg-01 cell lysates expressing a control (con) siRNA sequence, or Meg-01 cell lysates expressing a PPARγ siRNA sequence were incubated for 24 h with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM). HO-1 expression was analyzed by western blot.

15d-PGJ2 activates PPARγ in Meg-01 cells (ref Blood paper). To assess the role of PPARγ in HO-1 induction by 15d-PGJ2, Meg-01 cells were treated with natural and synthetic PPARγ ligands: 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM), 9,10 dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (10 μM), rosiglitazone (10 μM), and pioglitazone (10 μM). Hemin ( 1 μM), a well-described inducer of HO-1 (ref), was used as a positive control. 9,10 dihydo-15d-PGJ2 is a structural analog of 15d-PGJ2 that lacks the electrophilic carbon (5, 6, 21). Figure 2B demonstrates that only 15d-PGJ2 and hemin induced HO-1 in Meg-01 cells.

To further determine the role of PPARγ in 15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1, Meg-01 cells were infected with a lentiviral PPARγ siRNA to knock-down PPARγ expression. Meg-01 cells infected with a lentiviral PPARγ siRNA have a > 90% reduction in PPARγ protein (Fig. 2C). However, reducing PPARγ expression failed to attenuate 15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1 expression (Fig. 2D, lanes 4 and 6). In addition, treatment of Meg-01 cells with an irreversible PPARγ antagonist (GW9662) 1 h prior to 15d-PGJ2 addition failed to attenuate 15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1 (Fig. 2D, lane 2). Collectively, these small molecule and genetic approaches suggest that HO-1 induction by 15d-PGJ2 is independent of PPARγ.

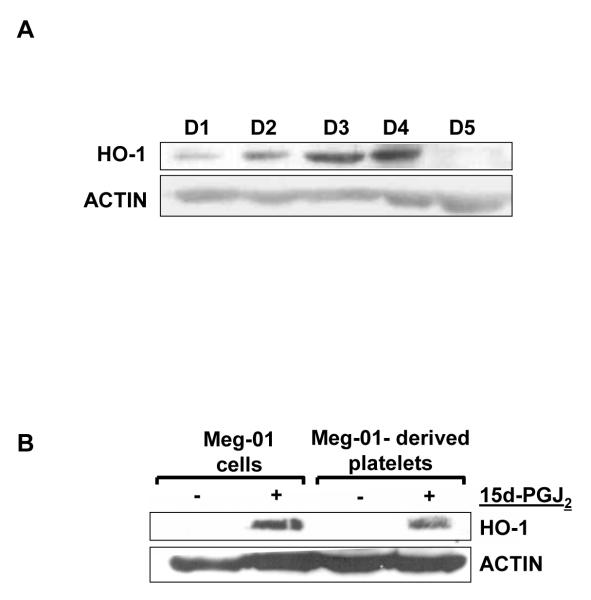

Daughter platelets derived from 15d-PGJ2-treated Meg-01 cells have elevated HO-1 protein levels

To investigate whether platelets express HO-1 we isolated platelets from five healthy donors (D1-D5) and western blotted for HO-1. Figure 3A demonstrates that human platelets express HO-1 protein. Interestingly, the level of HO-1 protein varied amongst the donors. We next investigated whether platelets derived from 15d-PGJ2-treated Meg-01 cells would also express HO-1. Platelets produced from 15d-PGJ2-treated Meg-01 cells also expressed HO-1 (Fig. 3B), whereas the platelets produced after 24 h in untreated Meg-01 cell cultures lacked HO-1. These data demonstrate that HO-1 is expressed in freshly isolated and culture-derived platelets.

Fig. 3.

Platelets express HO-1 protein. A) Western blot analysis of HO-1 protein in platelets purified from 5 healthy donors. B) Western blot analysis of HO-1 in platelets produced from Meg-01 cells that were untreated or treated with 15d-PGJ2.

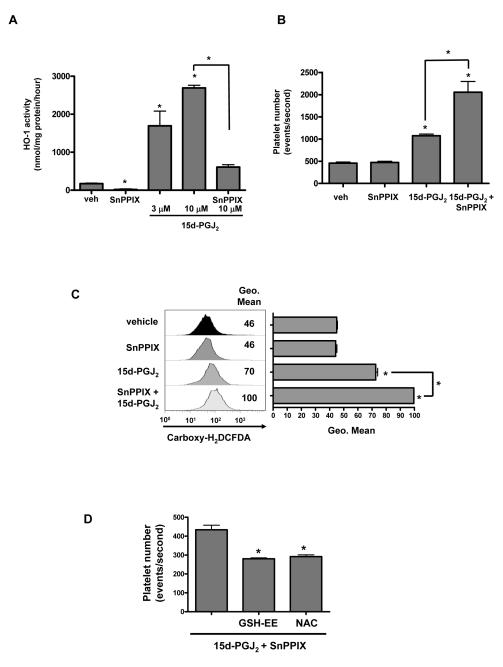

Inhibition of HO-1 enhances platelet production in Meg-01 cells

The function of HO-1 in human platelets is unknown. To first confirm that the 15d-PGJ2-mediated increase in HO-1 was associated with an increase in HO-1 activity, Meg-01 cells were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 in the presence or absence of tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPPIX), a well-described competitive inhibitor of human HO activity (22, 23). Meg-01 cells exhibited a basal level of HO activity, which was augmented by 15d-PGJ2 treatment (Fig. 4A). Addition of SnPPIX (5 μM) prevented the 15d-PGJ2-mediated increase. Interestingly, SnPPIX alone decreased HO activity.

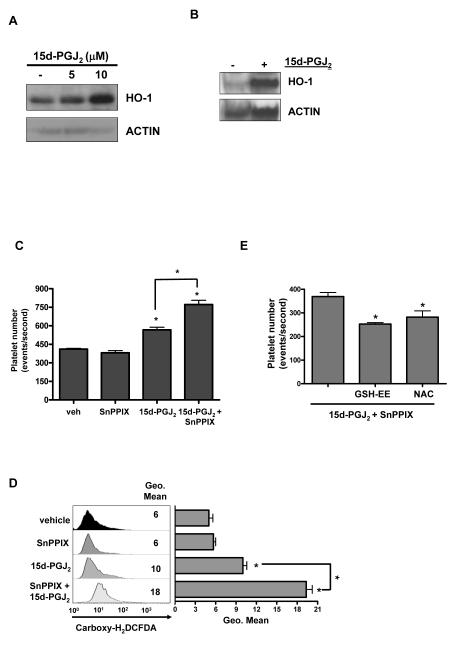

Fig. 4.

Inhibiting HO-1 activity enhances 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production by Meg-01 cells. A) Effect of 15d-PGJ2 on HO activity in Meg-01 cells in culture. Cells were treated with HO-1 inhibitor SnPPIX (5 μM) pretreatment (1-2 h) and incubated for 12 h with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM). Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05) (n=3). B) Effect of pretreating Meg-01 cells with SnPPIX on 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05). D) Effect of 15d-PGJ2 and the HO-1 inhibitor, SnPPIX, on ROS production. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05). D) Effect of antioxidants on 15d-PGJ2- and SnPPIX-induced platelet production. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05).

To investigate the role of HO-1 in platelet production, we treated Meg-01 cells with SnPPIX to inhibit HO-1 activity. Treating Meg-01 cells with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2, significantly enhanced platelet production when compared to 15d-PGJ2 treatment alone (Fig. 4B). This suggests that HO-1 regulates platelet production.

We previously reported that ROS are important for 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production (ref blood paper). Therefore, we hypothesized that HO-1 activity inhibits platelet production by protecting against 15d-PGJ2-induced oxidative stress. To test this we used carboxy-H2DCFDA to determine the effects of 15d-PGJ2 and SnPPIX on ROS generation. SnPPIX alone had no effect on ROS production (Fig. 4C), whereas treating Meg-01 cell with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2, significantly enhanced ROS production (P<0.05) compared to 15d-PGJ2 treatment alone (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, addition of antioxidants such as GSH-EE (5 mM) or NAC (1 mM), in conjunction with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2 addition, significantly reduced platelet production (Fig. 4D). These data support our hypothesis that the antioxidant properties of HO-1 are important for blunting platelet production.

15d-PGJ2-induced HO-1 in primary human megakaryocytes is inhibitory to platelet production

We next used primary human megakaryocytes to model thrombopoiesis. Interestingly, primary human megakaryocytes expressed a basal level of HO-1 that was dose-dependently induced by 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 5A). In addition, platelets produced from primary human megakaryocytes treated with 15d-PGJ2 also expressed elevated levels of HO-1 protein (Fig. 5B). Pretreating primary human megakaryocytes with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2 addition significantly enhanced platelet production when compared to 15d-PGJ2 treatment alone (Fig. 5C). As previously reported (ref. blood paper), 15d-PGJ2 induces ROS in primary human megakaryocytes. Treating with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2 significantly enhanced ROS production compared to 15d-PGJ2 treatment alone (Fig. 5D). Treatment with the antioxidant, GSH-EE (5 mM) or NAC (1 mM), in conjunction with SnPPIX prior to 15d-PGJ2 significantly reduced platelet enhancement (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these data provide compelling evidence that HO-1 dampens ROS generation thereby, inhibiting platelet release.

Fig. 5.

HO-1 activity inhibits 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet release in primary human megakaryocytes. A) Western blot analysis of HO-1 in primary human megakaryocytes. B) Western blot analysis of HO-1 in platelets produced from primary human megakaryocytes that were untreated or treated with 15d-PGJ2. C) Effect of pretreating primary human megakaryocytes with SnPPIX on 15d-PGJ2-induced platelet production. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05). D) Effect of 15d-PGJ2 and the HO-1 inhibitor, SnPPIX, on ROS production. E) Effect of antioxidants on 15d-PGJ2- and SnPPIX-induced platelet production. Results are presented as mean ± SD (P<0.05).

Discussion

Maturation of megakaryocytes and platelet production are complex processes orchestrated by cytokines, growth factors and transcription factors. Recently, our laboratory discovered that 15d-PGJ2 is a potent enhancer of megakaryocyte maturation and platelet production (ref. Blood paper). Here, we demonstrate that 15d-PGJ2 increases HO-1 protein expression in megakaryocytes as well as daughter platelets. Moreover, inhibition of HO-1 activity significantly increased platelet production. These new data highlight the importance of HO-1 in regulating platelet production.

15d-PGJ2 elicits a broad spectrum of biologic events that include the induction of antioxidant enzymes, including HO-1. 15d-PGJ2 increases HO-1 expression in macrophages, glial cells and myofibroblasts (24-26). Herein, we showed that 15d-PGJ2 potently increased HO-1 protein expression in Meg-01 cells and in primary human megakaryocytes (Fig. 1A, 5A) as well as HO-1 activity in Meg-01 cells (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, Meg-01 cells lack basal HO-1 expression (Fig. 1A), whereas primary human megakaryocytes modestly express HO-1 (Fig. 5A). We speculate that the difference in basal HO-1 expression between Meg-01 cells and primary human megakaryocytes is due to the stage of maturation, as several key platelet proteins are induced during megakaryopoiesis (17).

The ability of 15d-PGJ2 to increase HO-1 was independent of PPARγ. Inhibiting PPARγ utilizing the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, or inhibiting PPARγ expression had little effect on the ability of 15d-PGJ2 to augment HO-1. We speculate that the PPARγ-independent effect of 15d-PGJ2 relates to its electrophilic properties. PGJ2, 15d-PGJ2 and PGD2 all induced HO-1 (Fig. 2A). PGJ2 and 15d-PGJ2 both possess an α,β-unsaturated ketone within a cyclopentenone ring rendering both molecules highly electrophilic and chemically reactive in nature (27). Both PGD2 and 15d-PGD2 lack this α,β-unsaturated ketone. However, PGD2 is metabolized to electrophilic PGJ2 and 15d-PGJ2 inside the cell (20). In contrast, a 15d-PGJ2 structural analog, 9,10 dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (CAY10410), and other non-electrophilic PPARγ ligands, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone and 15d-PGD2, all failed to augment HO-1 (Fig. 2A, 2B). Therefore, the electophilic properties of 15d-PGJ2 are important for HO-1 induction.

We provide compelling evidence that HO-1 expression by megakaryocytes inhibits platelet production. The inhibition of HO-1 activity in combination with 15d-PGJ2 treatment significantly enhanced platelet production by megakaryocytes (Fig. 4B, 5C). We hypothesized that the antioxidant properties of HO-1 dampen platelet release from megakaryocytes. We previously reported that ROS generation was important for platelet production. Further, antioxidants such as NAC and GSH-EE attenuated 15d-PGJ2-enhanced platelet production (ref blood paper). Here we show that inhibiting HO-1 activity in conjunction with 15d-PGJ2 treatment significantly enhanced ROS generation compared to 15d-PGJ2 treatment alone (Fig. 4C, 5D). Interestingly, human HO-1 deficiency is characterized by both elevated levels of blood platelets and oxidative injury (8, 9). This is consistent with our data showing that inhibiting HO-1 activity increases both platelet number and ROS. Furthermore, Farkas, et al. recently demonstrated a negative association between HO-1 mRNA expression in venous blood and platelet number in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome (28). Since human platelets have different levels of HO-1 protein expression (Fig. 3A), we speculate that levels of HO-1 in human donor platelets may correlate with platelet number.

Since we demonstrated the ability of human megakaryocytes to induce HO-1 protein expression, we next wanted to determine if the HO-1 protein could be packaged into platelets during thrombopoiesis. Interestingly, the platelets derived from primary human megakaryocytes express a basal level of HO-1 similar to freshly isolated human platelets (Fig. 5B). Culture-derived Meg-01 platelets lacked basal HO-1 expression (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the platelets produced from both Meg-01 cells and primary human megakaryocytes following 15d-PGJ2 treatment exhibited elevated levels of HO-1 protein (Fig 3B, 5B). This demonstrates that alterations in key megakaryocyte proteins can be packaged into platelets and hence could influence platelet function.

It has been suggested that HO-1 induction contributes to the anti-inflammatory activities of 15d-PGJ2. For example, HO-1 induction by 15d-PGJ2 reduces fibrotic activity of myofibroblasts and myocardial infarct size in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction (26, 29). The ability of 15d-PGJ2 to elevate platelet HO-1 by elevating megakaryocyte HO-1 levels may have important implications for inflammation, such as reducing the risk of thrombotic events. Hemin-induced HO-1 in the carotid arterial wall inhibited platelet-dependent thrombus formation (30). HO-1 knockout mice exhibited accelerated, occlusive arterial thrombosis when compared to wild-type mice (31). Therefore, we speculate that platelet-specific HO-1 can also dampen thrombus formation.

The complex developmental biology of platelets coupled with the prevalence of disorders characterized by platelet activation, thrombocytosis and/or thrombocytopenia warrants research to understand mechanisms of thrombosis and thrombopoiesis. We have furthered the definition of the role of ROS in platelet production by providing strong evidence for an inhibitory role of HO-1 during thrombopoeisis. We demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 can increase platelet HO-1 levels by increasing megakaryocyte HO-1 levels. This suggests that 15d-PGJ2, by increasing platelet HO-1 levels, may be a promising anti-platelet therapy. Importantly, the idea that the platelet proteome and ultimately, platelet function, may be altered by influencing megakaryocyte protein levels suggests the megakaryocyte as a new target for platelet-directed pharmacotherapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by T32ES07026, HL078603, HL086367 and the PhRMA Foundation.

References

- 1.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83(5):803–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukushima M. Biological activities and mechanisms of action of PGJ2 and related compounds: an update. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1992;47(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(92)90178-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature. 1992;358(6389):771–4. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akbiyik F, Ray DM, Gettings KF, Blumberg N, Francis CW, Phipps RP. Human bone marrow megakaryocytes and platelets express PPARgamma, and PPARgamma agonists blunt platelet release of CD40 ligand and thromboxanes. Blood. 2004;104(5):1361–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colville-Nash PR, Qureshi SS, Willis D, Willoughby DA. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists: correlation with induction of heme oxygenase 1. J Immunol. 1998;161(2):978–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koizumi T, Negishi M, Ichikawa A. Induction of heme oxygenase by delta 12-prostaglandin J2 in porcine aortic endothelial cells. Prostaglandins. 1992;43(2):121–31. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(92)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60(1):79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawashima A, Oda Y, Yachie A, Koizumi S, Nakanishi I. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency: the first autopsy case. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(1):125–30. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yachie A, Niida Y, Wada T, Igarashi N, Kaneda H, Toma T, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(1):129–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray DM, Spinelli SL, Pollock SJ, Murant TI, O’Brien JJ, Blumberg N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and retinoid X receptor transcription factors are released from activated human platelets and shed in microparticles. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(1):86–95. doi: 10.1160/TH07-05-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh BJ, Tan BT, Hon WM, Lee KH, Khoo HE. Nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase expressions in human liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(4):588–94. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jozkowicz A, Huk I, Nigisch A, Weigel G, Weidinger F, Dulak J. Effect of prostaglandin-J(2) on VEGF synthesis depends on the induction of heme oxygenase-1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4(4):577–85. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motterlini R, Foresti R, Vandegriff K, Intaglietta M, Winslow RM. Oxidative-stress response in vascular endothelial cells exposed to acellular hemoglobin solutions. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(2 Pt 2):H648–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breton-Gorius J, Vainchenker W. Expression of platelet proteins during the in vitro and in vivo differentiation of megakaryocytes and morphological aspects of their maturation. Semin Hematol. 1986;23(1):43–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogura M, Morishima Y, Ohno R, Kato Y, Hirabayashi N, Nagura H, et al. Establishment of a novel human megakaryoblastic leukemia cell line, MEG-01, with positive Philadelphia chromosome. Blood. 1985;66(6):1384–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franks DJ, Mroske C, Laneuville O. A fluorescence microscopy method for quantifying levels of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-1 and CD-41 in MEG-01 cells. Biol Proced Online. 2001;3:54–63. doi: 10.1251/bpo23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel SR, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr The biogenesis of platelets from megakaryocyte proplatelets. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3348–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI26891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung I, Choudhury A, Lip GY. Platelet activation in acute, decompensated congestive heart failure. Thromb Res. 2007;120(5):709–13. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeuner A, Signore M, Martinetti D, Bartucci M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia derives from the selective death of megakaryocyte progenitors and can be rescued by stem cell factor. Cancer Res. 2007;67(10):4767–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata T, Kondo M, Osawa T, Shibata N, Kobayashi M, Uchida K. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. A prostaglandin D2 metabolite generated during inflammatory processes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(12):10459–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray DM, Akbiyik F, Phipps RP. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) ligands 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 and ciglitazone induce human B lymphocyte and B cell lymphoma apoptosis by PPARgamma-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2006;177(8):5068–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummond GS, Kappas A. Prevention of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia by tin protoporphyrin IX, a potent competitive inhibitor of heme oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(10):6466–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drummond GS, Kappas A. Chemoprevention of neonatal jaundice: potency of tin-protoporphyrin in an animal model. Science. 1982;217(4566):1250–2. doi: 10.1126/science.6896768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamura Y, Kakimura J, Matsuoka Y, Nomura Y, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Taniguchi T. Activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) inhibit inducible nitric oxide synthase expression but increase heme oxygenase-1 expression in rat glial cells. Neurosci Lett. 1999;262(2):129–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee TS, Tsai HL, Chau LY. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 expression in murine macrophages is essential for the anti-inflammatory effect of low dose 15-deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(21):19325–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Julien B, Grenard P, Teixeira-Clerc F, Mallat A, Lotersztajn S. Molecular mechanisms regulating the antifibrogenic protein heme-oxygenase-1 in human hepatic myofibroblasts. J Hepatol. 2004;41(3):407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxey KM, Hessler E, MacDonald J, Hitchingham L. The nature and composition of 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)PGJ(2) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;62(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farkas I, Maroti Z, Katona M, Endreffy E, Monostori P, Mader K, et al. Increased heme oxygenase-1 expression in premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayman NS, Hattori Y, McDonald MC, Mota-Filipe H, Cuzzocrea S, Pisano B, et al. Ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha) reduce myocardial infarct size. Faseb J. 2002;16(9):1027–40. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng L, Mundada L, Stomel JM, Liu JJ, Sun J, Yet SF, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 expression inhibits platelet-dependent thrombosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6(4):729–35. doi: 10.1089/1523086041361677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.True AL, Olive M, Boehm M, San H, Westrick RJ, Raghavachari N, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency accelerates formation of arterial thrombosis through oxidative damage to the endothelium, which is rescued by inhaled carbon monoxide. Circ Res. 2007;101(9):893–901. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]