Abstract

Rationale

Amisulpride is approved for clinical use in treating schizophrenia in a number of European countries and also for treating dysthymia, a mild form of depression, in Italy. Amisulpride has also been demonstrated to be an antidepressant for patients with major depression in many clinical trials. In part because of the selective D2/D3 receptor antagonist properties of amisulpride, it has long been widely assumed that dopaminergic modulation is the proximal event responsible for mediating its antidepressant and antipsychotic properties.

Objectives

The purpose of these studies was to determine if amisulpride’s antidepressant actions are mediated by off-target interactions with other receptors.

Materials and Methods

We performed experiments that: (1) examined the pharmacological profile of amisulpride at a large number of CNS molecular targets and (2) after finding high potency antagonist affinity for human 5-HT7a serotonin receptors, characterized the actions of amisulpride as an antidepressant in wild-type and 5-HT7 receptor knock-out mice.

Results

We discovered that amisulpride was a potent competitive antagonist at 5-HT7a receptors and that interactions with no other molecular target investigated here could explain its antidepressant actions in vivo. Significantly, and in contrast to their wildtype littermates, 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice did not respond to amisulpride in a widely used rodent model of depression, the tail suspension test.

Conclusions

These results indicate that 5-HT7a receptor antagonism, and not D2/D3 receptor antagonism, likely underlies the antidepressant actions of amisulpride.

Keywords: amisulpride, 5-HT7, 5-HT7 antagonist, antidepressant, atypical antipsychotic, DAN 2163

Introduction

Amisulpride is a benzamide derivative that was initially developed as a selective D2/D3 receptor antagonist for the treatment of schizophrenia (Perrault et al. 1997). Amisulpride has been shown to be as or more effective than various comparators in the treatment of schizophrenia in a large number of clinical trials (Racagni et al. 2004). Meta-analyses have identified clozapine, amisulpride, risperidone, and olanzapine as being significantly more effective than first generation (typical) antipsychotics and other second generation (atypical) antipsychotics (Davis et al. 2003), (Leucht et al. 2009). Clinically, amisulpride is characterized by a side effect profile most resembling that of an atypical antipsychotic, due to its low extrapyramidal symptom (EPS) burden (Leucht et al. 2002). However, like risperidone and first generation antipsychotic drugs, amisulpride causes large elevations in serum prolactin levels, most likely due to its potent D2/D3 antagonist properties (Wetzel et al. 1998). Thus, despite having a pharmacological profile reminiscent of a typical antipsychotic in that it exhibits high D2 affinity and low 5-HT2A affinity, amisulpride therapeutically resembles atypical antipsychotics. Amisulpride has also been reported to improve the cognitive domains of attention, executive function, and working memory, as well as the global cognitive index in patients with schizophrenia (Deeks and Keating 2008), and declarative memory in another study (Mortimer et al. 2007). However, it has also been shown to impair recognition memory in normal subjects (Gibbs et al. 2008), (Mortimer et al. 2007).

Interestingly, there is evidence that amisulpride has antidepressant properties in both schizophrenia (Kim et al. 2007) and other psychiatric disorders (Montgomery 2002). Amisulpride is approved for treating dysthymia in Italy (Pani and Gessa 2002) and has been shown to be a highly effective antidepressant (Montgomery 2002). In fact, amisulpride has been shown to as effective as imipramine in patients with dysthymia and major depression, as measured by the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Lecrubier et al. 1997). In another study, amisulpride was as effective as fluoxetine in treating major depression and dysthymia (Smeraldi 1998). Amisulpride was also similar to fluoxetine in terms of the percent of subjects with dysthymia or major depression who responded to treatment, the number of adverse events, and dropout rates (Smeraldi 1998). In fact, amisulpride has been shown to be as effective as comparator in humans in at least six clinical studies in patients with dysthymia and/or major depression (Racagni et al. 2004).

The presumed selectivity of amisulpride for D2 and D3 dopamine receptors has led to the prevailing hypothesis that modulation of dopaminergic signaling is responsible for its antidepressant efficacy. Indeed, a role for dopamine in antidepressant action is plausible. Multiple antidepressants from different classes, including fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and desipramine, increase extracellular dopamine in the prefrontal cortex of rats (Tanda et al. 1994), (Jordan et al. 1994), (Bymaster et al. 2002). On the other hand, sulpride, another benzamide derivative with selectivity for D2/D3 receptors, significantly reduces the antidepressant efficacy of desipramine in the forced swim test in rats when bilaterally injected into the nucleus accumbens, but not the caudate putamen (Cervo and Samanin 1987). Furthermore, although it has been suggested that sulpride has antidepressant effects in humans, its efficacy in this regard was found to be much smaller than that seen with the comparator, amitryptiline (Drago et al. 2000). Overall, with the exception of amisulpride, none of the benzamides are well established as exhibiting antidepressant activity comparable to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclics.

While the evidence is strong that some antidepressants can modulate dopaminergic systems, there is little or no evidence, other than the aforementioned phenomenological data, that selective dopamine receptor antagonists such as haloperidol have antidepressant effects as monotherapy absent action at any other targets. For instance, aripiprazole is approved for adjunctive treatment of depression although it has significant off-target actions at many biogenic amine receptors and transporters implicated in antidepressant drug actions (Shapiro et al. 2003). Olanzapine has also been shown to be an effective adjunctive agent to antidepressants in some studies with treatment resistant or bipolar depression (Deeks and Keating 2008). Additionally, quetiapine’s antidepressant actions are most likely due to potent inhibition of the norepinephrine transporter by its main metabolite N-desalkyl-quetiapine (Jensen et al. 2008) and not to any direct actions on dopamine receptors. Thus, we set out to test the hypothesis that the antidepressant action of amisulpride results from D2/D3 receptor antagonism. We screened amisulpride at a large number of CNS targets in the hopes of identifying and then characterizing target(s) responsible for its antidepressant actions.

Materials and Methods

Radioligand binding assays

Radioligands were purchased from Perkin-Elmer or GE Healthcare. Competition binding assays were performed using transfected or stably-expressing cell membrane preparations as previously described (Shapiro et al. 2003), (Roth et al. 2002) and are available on-line (http://pdsp.med.unc.edu). Key information such as radioligand identity, radioligand concentration, incubation buffer, and incubation time are in Table 1 and additional information is available on-line (http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/UNC-CH$20Protocol%20Book.pdf).

Table 1.

Ki estimates for amisulpride at a large panel of cloned receptors

| Receptor | Ki | Radioligand | Incubation Buffer |

Incubation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]8-OH-DPAT | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT1B | 1744 ± 199 nM | .3 nM [3H]5-CT | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT1D | 1341 ± 217 nM | .3 nM [3H]5-CT | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT1E | > 10,000 nM | 3 nM [3H]5-HT | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT2A | 8304 ± 1579 nM | .5 nM [3H]ketanserin | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT2B | 13 ± 1.12 nM | 1.1 nM [3H]LSD | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT2C | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]N-methyl-mesulergine | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT3 | > 10,000 nM | .29 nM [3H]LY278584 | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT5A | > 10,000 nM | 1 nM [3H]LSD | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT6 | 4154 ± 599 nM | 1.05 nM [3H]LSD | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT7 | 11.5 ± .71 nM | 1.05 nM [3H]LSD | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| 5-HT7a | 135.5 ± 15.8 nM | .35 nM [3H]5-CT | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| α1a | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]HEAT | A1BB | 1 hour |

| α1b | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]HEAT | A1BB | 1 hour |

| α1d | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]HEAT | A1BB | 1 hour |

| α2a | 1114 ± 124 nM | .1 nM [125I]clonidine | A2BB | 1 hour |

| α2c | 1540 ± 171 nM | .1 nM [125I]clonidine | A2BB | 1 hour |

| β1 | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]iodopindolol | BBB | 1 hour |

| β2 | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]iodopindolol | BBB | 1 hour |

| β3 | > 10,000 nM | .1 nM [125I]iodopindolol | BBB | 1 hour |

| Benzodiazapene | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]flunitrazepam | BZPBB | 1.5 hours |

| D1 | > 10,000 nM | .21 nM [3H]SCH23390 | DBB | 1.5 hours |

| D2 | 3 ± 1 nM | .19 nM [3H]N-methyl-spiperone | DBB | 1.5 hours |

| D3 | 3.5 ± .5 nM | .35 nM [3H]N-methyl-spiperone | DBB | 1.5 hours |

| D4 | 2369 ± 608 nM | .19 nM [3H]N-methyl-spiperone | DBB | 1.5 hours |

| D5 | > 10,000 nM | .21 nM [3H]SCH23390 | DBB | 1.5 hours |

| DOR | > 10,000 nM | .3 nM [3H]DADLE | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| KOR | > 10,000 nM | .3 nM [3H]U69593 | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| MOR | > 10,000 nM | .3 nM [3H]DAMGO | SBB | 1.5 hours |

| H1 | > 10,000 nM | .9 nM [3H]pyrilamine | HBB | 1.5 hours |

| H2 | > 10,000 nM | 3 nM [3H]tiotidine | HBB | 1.5 hours |

| H4 | > 10,000 nM | 5 nM [3H]histamine | HBB | 1.5 hours |

| M1 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]QNB | MBB | 1.5 hours |

| M2 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]QNB | MBB | 1.5 hours |

| M3 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]QNB | MBB | 1.5 hours |

| M4 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]QNB | MBB | 1.5 hours |

| M5 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]QNB | MBB | 1.5 hours |

| DAT | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]WIN35428 | TBB | 1.5 hours |

| NET | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]nisoxetine | TBB | 1.5 hours |

| SERT | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]citalopram | TBB | 1.5 hours |

| EP3 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]PGE2 | PBB | 1.5 hours |

| EP4 | > 10,000 nM | .5 nM [3H]PGE2 | PBB | 1.5 hours |

| σ1 | > 10,000 nM | 3 nM [3H]pentazocine | SigmaBB | 2.5 hours |

| σ2 | > 10,000 nM | 3 nM [3H]DTG | SigmaBB | 2.5 hours |

Standard Binding Buffer (SBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4

Dopamine Binding Buffer (DBB): 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4

Histamine Binding Buffer (HBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4

Transporter Binding Buffer (TBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, pH 7.4

Prostaglandin Binding Buffer (PBB): 25 mM Tris HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4

Alpha1 Binding Buffer (A1BB): 20 mM Tris HCl, 145 mM NaCl, pH 7.4

Alpha2 Binding Buffer (A2BB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.7

Beta Binding Buffer (BBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 3 mM MnCl2, pH 7.7

Muscarinic Binding Buffer (MBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.7

Sigma Binding Buffer (SigmaBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0

Benzodiazapene Binding Buffer (BZPBB): 50 mM Tris HCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4

Schild analysis

Cells stably expressing 5-HT7a receptors were sub-cultured into a 96 well white OptiPlate 96 (Perkin-Elmer) at 10,000 cells per well in DMEM with 1% dialyzed FBS overnight. Culture media was removed and replaced with assay media (DMEM containing 2 mM IBMX and 10 mg/100 ml ascorbic acid) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The pre-incubation media was then aspirated off, and 5 µL/well of amisulpride in the above assay media was added at 10X of the final concentrations (0, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 nM). Five minutes later, 5 µL/well of 5-HT was added at 10X of the final concentrations (0, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300, 1000, and 3000 nM). The assay was designed to generate a 5-HT dose-response curve in duplicate in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of amisulpride at every concentration point. The reaction proceeded for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cAMP production was determined with GE's HitHunter cAMP XS+ kit according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, at the end of 30min reaction, cAMP antibody reagent was added, immediately followed by a mixture of Galacton-Star, Emerald-II, lysis buffer and cAMP XS+ ED reagent at a 1:5:19:25 ratio. After a one hour incubation at room temperature, the cAMP XS+ EA reagent was added. The plate was incubated for another hour at room temperature. Luminescence signals were then read using a standard Beta counter. Data were processed in Microsoft Excel and Graphpad Prism. Data were globally fit in Graphpad Prism to the modified Gaddum/Schild model combined with the Hill equation (Motulsky and Christopoulos 2004). An extra sum of squares F-test was performed to assess whether or not the Schild and Hill slopes were significantly different from unity.

Animals

Ten-to-twelve week old male 5-HT7−/− mice and their male 5-HT7+/+ sibling controls were used. The generation of the 5-HT7−/− mouse strain has been described previously (Hedlund et al. 2003). The mice used in this study had been back-crossed on a C57BL/6J background for at least 16 generations. All behavioral experiments were started at 09.00 h. The mice were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 06.00 and off at 18.00) and had free access to water and food pellets. All the experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the US National Institutes of Health, and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at The Scripps Research Institute. Every effort was made to reduce the number of animals used and to minimize potential suffering.

Tail suspension test

The tail suspension test was performed as previously described (Hedlund et al. 2005). Briefly, mice were suspended from a metal rod mounted 50 cm above the surface by fastening the tail to the rod with adhesive tape. The duration of the test was 6 minutes and immobility was measured during the last 4 minutes to facilitate comparison with previous studies. Immobility was defined as the absence of any limb or body movements, except those caused by respiration.

Forced swim test

The forced swim test was performed as previously described (Hedlund et al. 2005). Briefly, mice were gently placed in a clear plastic cylinder, diameter of 16 cm, height 25 cm, filled with 10 cm of clear water at 25°C. Test duration was six minutes and immobility was measured during the last four minutes. Immobility was defined as the absence of any horizontal or vertical movement in the water, but excluded minor movements required for the mouse to keep its head above the surface. The water was replaced before each animal.

Drug treatments

For the tail suspension test and forced swim test, single intra-peritoneal injections were given 30 minutes prior to the test. Amisulpride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The drug was dissolved in 50 mM tartaric acid in 0.9% NaCl and administered in the doses indicated in a total volume of 0.2 ml. The vehicle alone was used as control.

Data analysis

All values are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean (S.E.M.). Possible differences between genotypes and/or drug treatments were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with genotype as one factor and drug treatment as the other factor. The ANOVA was followed by an appropriate Bonferroni post test. All analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software package. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Amisulpride has high affinity for human 5-HT7a receptors

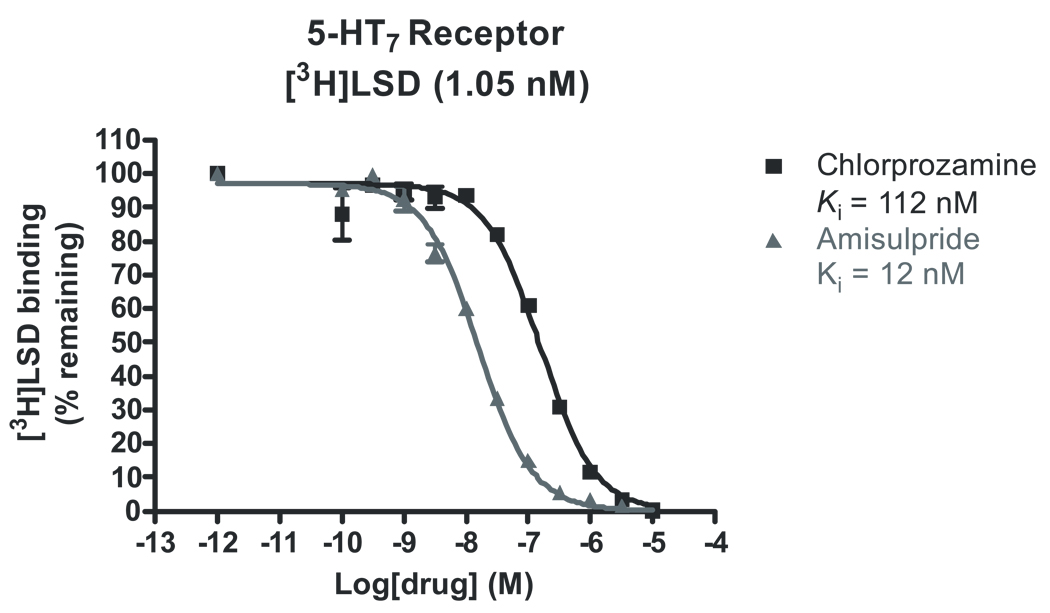

In order to identify targets that might explain the antidepressant efficacy of amisulpride, we undertook a large screen of potential targets using our receptorome profiling approach (Armbruster and Roth 2005) (Table 1). Our screen confirmed that amisulpride was potent and selective at D2 and D3 dopamine receptors. Amisulpride bound D2 receptors with a Ki of 3 ± 1 nM and D3 receptors with a Ki of 3.5 ± 0.5 nM. However, amisulpride also had high affinity for two previously unidentified targets. These were the 5-HT2B serotonin receptor, which bound amisulpride with a Ki of 13 ± 1 nM, and the 5-HT7a serotonin receptor, at which amisulpride had a Ki of 11.5 ± .7 nM against [3H]LSD, which has a reported Kd of 6.6 nM for 5-HT7a receptors (Shen et al. 1993), (Roth et al. 1994) (Figure 1). Amisulpride had low affinity for h5-HT1A serotonin receptors and other molecular targets implicated in antidepressant drug actions (Roth et al. 2004).

Figure 1.

Amisulpride (▲) and chlorpromazine (■) versus [3H]LSD competition binding at 5-HT7a receptors. Amisulpride competes effectively against the high affinity 5-HT7a antagonist chlorpromazine at cloned h5-HT7a receptors, suggesting that it binds with high affinity to 5-HT7a receptors.

Amisulpride is a potent human 5-HT7a receptor antagonist

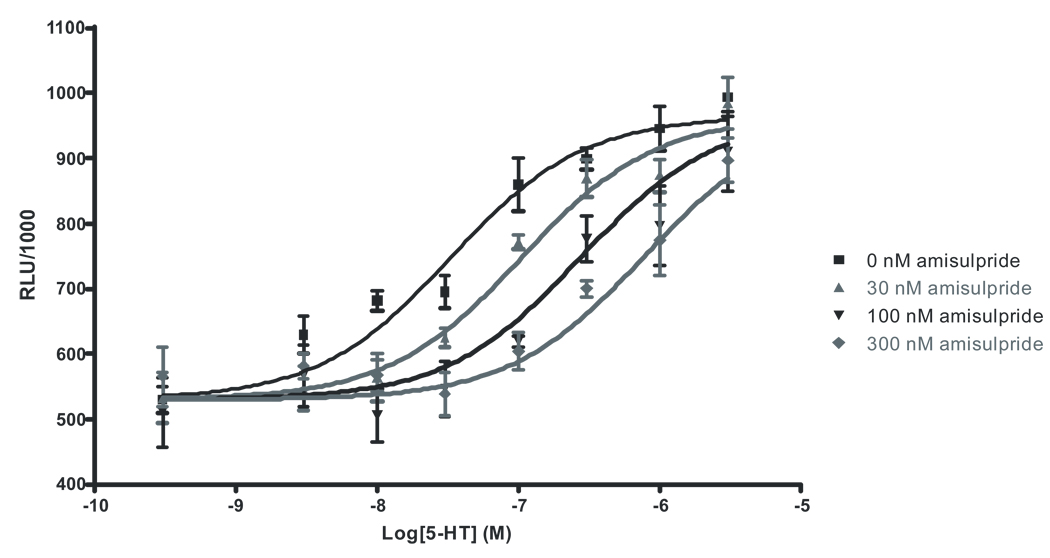

Our initial screen identified the h5-HT7a serotonin receptor as a high affinity target of amisulpride. Multiple splice variants of the 5-HT7 receptor have been shown to exist in rodent and human (Heidmann et al. 1997), and it has been shown that 5-HT7a is by far the most common isoform in vivo in rats, though the different variants are indistinguishable in terms of 5-HT affinity and potency (Heidmann et al. 1998). Since drugs appear to exhibit identical pharmacological characteristics at the different 5-HT7 splice variants, we performed all amisulpride screening and characterization at the most highly expressed variant, 5-HT7a. We elaborated on our findings by performing another set of competition assays, this time competing amisulpride against [3H]5-CT, which has sub-nanomolar affinity for 5-HT7a receptors (Thomas et al. 1998), (To et al. 1995) (Figure 2). [3H]5-CT preferentially labels the high-affinity, agonist state of the receptor, while [3H]LSD, a weak partial agonist, labels mostly low affinity, antagonist sites. We predicted that if amisulpride was a 5-HT7a receptor antagonist, it should have preferentially lower affinity for [3H]5-CT labeled vs [3H]LSD sites. Indeed, amisulpride had a much lower affinity for [3H]5-CT-labeled 5-HT7a receptors (Ki = 135.5 ± 15.8 nM), suggesting that it is an antagonist. In confirmation of this finding, initial studies indicated that amisulpride did not induce cAMP accumulation (data not shown). Next, we generated dose response curves for 5-HT activation of 5-HT7a receptors in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of amisulpride, the putative antagonist. We then used non-linear least squares regression to globally fit the dose response curves to the modified Gaddum/Schild equation (Motulsky and Christopoulos 2004). As can be seen, increasing concentrations of amisulpride shifted the dose response curve for 5-HT activation of 5-HT7a receptors to the right in a parallel fashion, suggesting that amisulpride is a reversible, competitive antagonist (Figure 3). An extra sum of squares F-test determined that the Schild slope was not significantly different from a value of 1, which indicates that amisulpride is a 5-HT7a receptor competitive antagonist. The pA2 (7.94 ± .08) derived from globally fitting the Gaddum/Schild equation thus provides an estimate of the Kd (11.4 ± .8 nM) which is consistent with our earlier Ki affinity estimates at the [3H]LSD labeled receptor sites. Thus, we have established that amisulpride is a high affinity competitive antagonist at the 5-HT7a receptor.

Figure 2.

Amisulpride (▲) and 5-HT (■) versus [3H]5-CT competition binding at 5-HT7a receptors. The comparatively low affinity of amisulpride for [3H]5-CT, a 5-HT7a agonist with high intrinsic activity that preferentially binds high affinity sites, in contrast with its higher affinity for [3H]LSD, a very weak partial agonist that labels primarily low affinity antagonist binding sites, suggests that amisulpride is an antagonist at 5-HT7a receptors.

Figure 3.

The modified Gaddum/Schild equation-fitted dose response data for 5-HT activation of 5-HT7a receptors in the presence of 0, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 nM amisulpride. All dose response data generated in the presence of all seven amisulpride concentrations were fitted to generate the curves shown: 0, 10, 30, and 100 nM amisulpride. There appears to be a parallel, rightward shift of the dose response curves in the presence of increasing concentrations of amisulpride, suggesting that amisulpride is a competitive antagonist at 5-HT7a receptors.

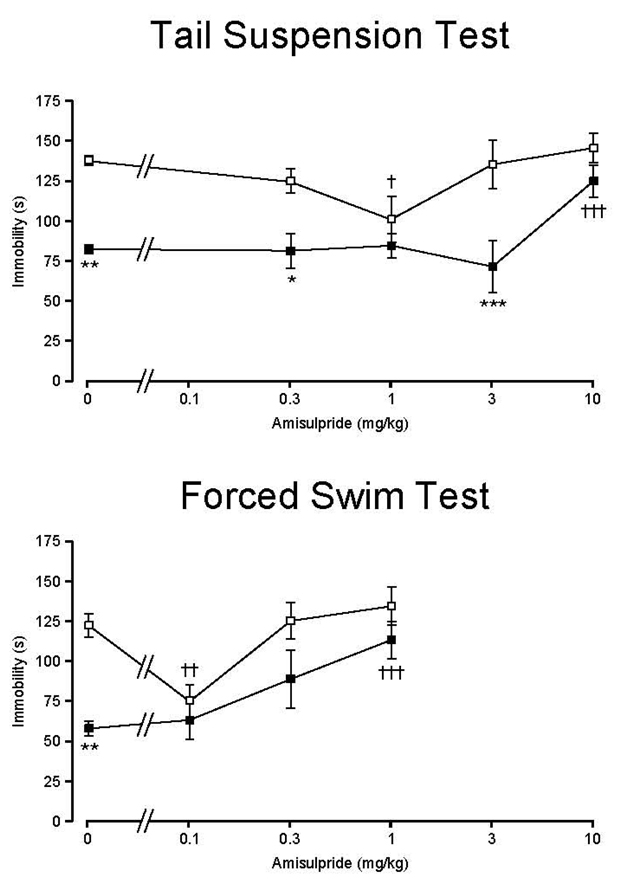

The 5-HT7 receptor mediates the antidepressant effects of amisulpride in vivo

Our identification of the 5-HT7a receptor as a novel target for amisulpride suggested that 5-HT7 receptors might be the target mediating its antidepressant actions in vivo. We predicted that, if 5-HT7 receptors were the critical mediator of the antidepressant effects of amisulpride, then amisulpride should lack antidepressant efficacy in 5-HT7−/− mice. As previously reported (Hedlund et al. 2005) (Guscott et al. 2005), 5-HT7−/− mice showed lower immobility time than 5-HT7+/+ mice in the tail suspension test (TST) and the forced swim test (FST) when given vehicle only. Amisulpride displayed a U-shaped dose-response effect in 5-HT7+/+ mice (Figure 4) in both the TST and the FST, though the effective dose of amisulpride was different in the two depression models. In 5-HT7+/+ mice the immobility time was significantly reduced at 1 mg/kg in TST and 0.1 mg/kg in FST, which is consistent with the expected antidepressant effect of the drug. On the other hand, amisulpride in doses less than 10 mg/kg in TST and less than 1 mg/kg in FST did not affect immobility in 5-HT7−/− mice (i.e., exerted no antidepressant efficacy). At 10 mg/kg of amisulpride in TST and 1 mg/kg in FST, the immobility response was significantly increased in 5-HT7−/− mice to the level of 5-HT7+/+ mice, likely due to extra-pyramidal actions at these higher doses. Similarly, the clear antidepressant effect disappears at higher doses (3 and 10 mg/kg in TST and .3 and 1 mg/kg in FST) in 5-HT7+/+ mice. This low dose antidepressant effect of amisulpride is consistent with the clinical literature (Racagni et al. 2004).

Figure 4.

Dose-response effect of amisulpride on the immobility profile of 5-HT7+/+ (□) and 5-HT7−/− (■) mice in (upper panel) the tail suspension test and (lower panel) the forced swim test. Amisulpride shows a dose-dependent antidepressant efficacy in both depression models by reducing immobility time in 5-HT7+/+ but not 5-HT7−/− mice. Values are mean ± SEM. n = 6 animals per genotype per treatment group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001 between the genotypes; †p < 0.05, †††p < 0.001 within a genotype compared to control; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test.

Discussion

The main findings of this paper are that amisulpride is a potent 5-HT7a receptor antagonist and that its antidepressant actions (as assessed by the TST) require functional 5-HT7 receptors in vivo. The unique therapeutic profile of amisulpride has proven difficult to explain in light of its known pharmacological profile. There is some evidence that amisulpride has some selectivity for presynaptic dopamine autoreceptors, and exhibits limbic versus striatal selectivity, particularly at low doses, and it has been suggested that this might account for its therapeutic profile (Schoemaker et al. 1997). It should be noted, however, that haloperidol has similar effects at presynaptic dopamine autoreceptors, while another benzamide derivative, sulpride, also exhibits virtually identical limbic selectivity (Schoemaker et al. 1997). Sulpride, which exhibits similar D2/D3 selectivity when compared to amisulpride, and the related substituted benzamides raclopride, remoxipride, and metoclopramide, do not bind to 5-HT7 receptors (Roth et al. 1994). Sulpride has a very small antidepressant effect in humans, despite an apparently similar pharmacological profile to amisulpride (Drago et al. 2000). It also appears to have a depressant effect when given in conjunction with an antidepressant in rat models of depression, as it leads to a substantial reinstatement of depression (Cervo and Samanin 1987). The evidence that antidepressants modulate dopamine levels in prefrontal cortex (Tanda et al. 1994) further suggests that dopamine may play some role in mediating their efficacy, though little to no evidence exists that modulation of dopaminergic signaling is sufficient or necessary for amisulpride’s antidepressant actions.

Indeed, the only antidepressant for which any case can be made for a solely dopaminergic mode of action is amisulpride, due to its apparent selectivity for D2/D3 receptors and well established clinical antidepressant efficacy. Given the inconsistency of the literature with respect to the effect of dopaminergic agents on depression, and the known lack of antidepressant efficacy of other closely related benzamides, we hypothesized that some other target might explain the antidepressant actions of amisulpride. We thus began by performing a parallel screen at a large panel of cloned receptors with the aim of identifying a hitherto unidentified target for amisulpride. The results of our screen were consistent with a previous screen (Schoemaker et al. 1997) in indicating that amisulpride is relatively selective for D2/D3 receptors. We identified two previously unreported targets, however: 5-HT2B and 5-HT7a. Agonists at the 5-HT2B receptor have been associated with cardiac valvulopathy (Rothman et al. 2000), (Roth 2007), (Berger et al. 2009), while 5-HT2B antagonists such as amisulpride (Huang et al, submitted) appear to be safe. There is no evidence that 5-HT2B receptors can mediate any therapeutic actions of amisulpride. On the other hand, the 5-HT7 receptor (Shen et al. 1993), (Lovenberg et al. 1993), (Bard et al. 1993) has been consistently implicated in numerous studies in the etiology of circadian rhythm regulation, mood, sleep architecture, thermoregulation, depressive behaviors (Hedlund and Sutcliffe 2004), (Berger et al. 2009), and antipsychotic drug actions (Roth et al. 1994), making it a promising candidate target for mediating the antidepressant effects of amisulpride.

Indeed, we found that amisulpride is a potent competitive 5-HT7a receptor antagonist. We thus hypothesized that antagonism of 5-HT7a receptors was likely to be responsible for the antidepressant efficacy of amisulpride. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vivo approach, predicting that amisulpride would no longer be efficacious in mice in which the 5-HT7 receptor has been genetically deleted. As expected, low dose amisulpride had no antidepressant effect in the TST and FST in 5-HT7−/− mice, despite its efficacy in 5-HT7+/+ littermates. This is unlikely to be due to a “floor effect” in 5-HT7−/− mice resulting from their lower baseline immobility time, as it has been shown that citalopram, an SSRI antidepressant, reduces TST immobility time in both 5-HT7+/+ and 5-HT7−/− mice (Hedlund et al. 2005). The roughly 25% reduction in TST immobility time seen in 5-HT7+/+ mice after treatment with amisulpride is consistent with the previously reported effect of the 5-HT7 antagonist SB269970 in TST, and not as large as the 50% or greater reduction seen with the SSRI citalopram (Hedlund et al. 2005). Finally, the increase in immobility time at higher doses of amisulpride is consistent with the reported immobility-increasing effects of the D2/D3 antagonist (−)eticlopride in TST (Ferrari and Giuliani 1997), which further suggests that D2/D3 antagonism cannot explain the antidepressant efficacy of amisulpride. Thus, the clear conclusion is that 5-HT7 receptors are critical mediators of the antidepressant actions of amisulpride in vivo in the TST and FST, the best established animal models of depression.

Studies of the effects of drugs that target 5-HT7 receptors are highly consistent with our hypothesis. As shown previously and in this study, 5-HT7−/− mice exhibit significantly less immobility time in the TST (Hedlund et al. 2005) and FST (Hedlund et al. 2005), (Guscott et al. 2005), which is consistent with the idea that reducing 5-HT7 receptor signaling has antidepressant effects. While SB269970, a selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, reduced immobility time in the TST and FST in 5-HT7+/+ mice, it had no effect in 5-HT7−/− mice (Hedlund et al. 2005). This antidepressant effect of SB269970 in TST and FST has been confirmed in at least one other study (Wesolowska et al. 2006). Finally, another 5-HT7 antagonist, SB258719, has been shown to reduce immobility time in FST (Guscott et al. 2005).

It is worth noting that chronic fluoxetine treatment has been shown to downregulate 5-HT7 receptors in the hypothalamus (Sleight et al. 1995), (Mullins et al. 1999), thus correlating antidepressant efficacy with changes in 5-HT7 receptor signaling, further evidence that a reduction in 5-HT7 receptor signaling may be beneficial with respect to treating depression. Another important physiological parameter that is affected by antidepressant treatment is sleep. Changes in sleep architecture have long been known to be associated with depression. Depressed subjects exhibit shorter latency time to the first entry into rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and increased total REM sleep time (Brunello et al. 2000). Most antidepressants normalize sleep architecture problems, increasing REM latency and decreasing total REM sleep time (Staner et al., 1999). The ability of antidepressants to normalize the sleep architecture abnormalities seen in depressed patients has been positively associated with clinical response in a number of studies, though a few studies have been unable to replicate this finding (Ott et al. 2002). Not surprisingly, the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-656104-A initiates REM sleep changes consistent with those caused by most SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants, increasing latency to the start of REM sleep and decreasing total REM sleep time (Thomas et al. 2003). Furthermore, 5-HT7−/− mice spend less time in REM sleep (Hedlund et al. 2005). Finally, there is some evidence that 5-HT7 receptor antagonism may affect neuronal morphology (Kvachnina et al. 2005) and stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis alone (Nandam et al. 2007), (Kodama et al. 2004) or synergistically with another antidepressant (Xu et al. 2006). This is consist with antidepressant activity, since antidepressant efficacy has been correlated with hippocampal neurogenesis in some (Santarelli et al. 2003), (Malberg et al. 2000), but not all (Holick et al. 2008), studies. Thus, 5-HT7 receptor antagonists initiate a number of the same physiological changes as commonly prescribed SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants.

The prevailing notion that amisulpride exerts its well established clinical antidepressant effects by antagonizing D2/D3 receptors results primarily from two lines of reasoning. First, an early screen of amisulpride showed that amisulpride appeared to be selective for D2/D3 receptors, suggesting that any therapeutic efficacy of the drug must be mediated by that action. Second, a number of studies have shown that antidepressants affect dopamine and dopamine receptors, leading to the hypothesis that changes in the dopaminergic system may be an important component of antidepressant drug actions (Dailly et al. 2004). Nonetheless, the idea that the antidepressant effects of amisulpride are mediated via D2/D3 antagonism is problematic for a number of reasons. First, and perhaps most prominently, no other D2/D3 antagonist, including other benzamide derivatives, appears to be a highly effective antidepressant in either animal models or humans. Second, though the evidence is strong that there are dopaminergic changes in response to antidepressant treatment, nothing indicates that these phenomena are crucial for antidepressant actions.

Our identification of the 5-HT7a receptor as a target blocked by amisulpride suggests a plausible explanation for its antidepressant efficacy. Changes in 5-HT7 receptor function have been shown to result from chronic antidepressant treatment (Sleight et al. 1995), (Mullins et al. 1999). Furthermore, 5-HT7−/− mice exhibit less immobility time in the TST and FST when compared to their littermates (Hedlund et al. 2005), (Guscott et al. 2005) and 5-HT7a receptor antagonists are effective in animal models of depression (Hedlund et al. 2005) and have the same effects on sleep architecture as most antidepressants (Hedlund et al. 2005), (Wesolowska et al. 2006). 5-HT7 receptor antagonists and presently approved antidepressants also appear to have similar effects on hippocampal neurogenesis (Kvachnina et al. 2005). Finally, many antidepressant drugs bind 5-HT7 receptors with high affinity, suggesting the possibility that actions at 5-HT7 receptors may therapeutically complement the antidepressant efficacy of their other pharmacological activities, thereby enhancing their efficacy (Shen et al. 1993). Thus, there are multiple lines of evidence suggesting that 5-HT7a receptors might be mediating the antidepressant effects of amisulpride in vivo. Our data showing that amisulpride has no antidepressant effect in 5-HT7−/− mice makes any other conclusion as to the mechanism of action of the antidepressant efficacy of amisulpride highly problematic. Additionally, the finding that amisulpride is a highly effective antidepressant via antagonism at 5-HT7 receptors would make its mechanism of action a unique one relative to other approved antidepressant drugs and supports the development and/or testing of more selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonists to treat depression in humans.

Acknowledgements

A.A., X.P.H., T.B.T., and B.L.R. were supported by NIMH61887, U19MH82441, and the NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program; B.L.R. received additional support as a NARSAD Distinguished Investigator. A.A. was also supported by the CWRU MSTP and NIH T32 GM007250. P.B.H. was supported by NIMH MH73923.

Contributor Information

Atheir I. Abbas, Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

Peter B. Hedlund, Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA

Xi-Ping Huang, National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27516, USA.

Thuy B. Tran, National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27516, USA

Herbert Y. Meltzer, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37215, USA

Bryan L. Roth, Departments of Pharmacology and Psychiatry, and Lineberger Cancer Center, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27516, USA Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27516, USA; National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27516, USA.

References

- Armbruster BN, Roth BL. Mining the receptorome. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5129–5132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard JA, Zgombick J, Adham N, Vaysse P, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Cloning of a novel human serotonin receptor (5-HT7) positively linked to adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23422–23426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunello N, Armitage R, Feinberg I, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Leger D, Linkowski P, Mendelson WB, Racagni G, Saletu B, Sharpley AL, Turek F, Van Cauter E, Mendlewicz J. Depression and sleep disorders: clinical relevance, economic burden and pharmacological treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42:107–119. doi: 10.1159/000026680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Carter PA, Shaw J, Chernet E, Phebus L, Wong DT, Perry KW. Fluoxetine, but not other selective serotonin uptake inhibitors, increases norepinephrine and dopamine extracellular levels in prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Samanin R. Evidence that dopamine mechanisms in the nucleus accumbens are selectively involved in the effect of desipramine in the forced swimming test. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1469–1472. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailly E, Chenu F, Renard CE, Bourin M. Dopamine, depression and antidepressants. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18:601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:553–564. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks ED, Keating GM. Olanzapine/fluoxetine: a review of its use in the treatment of acute bipolar depression. Drugs. 2008;68:1115–1137. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868080-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago F, Arezzi A, Virzi A. Effects of acute or chronic administration of substituted benzamides in experimental models of depression in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F, Giuliani D. Effects of (−)eticlopride and 7-OH-DPAT on the tail-suspension test in mice. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11:339–344. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A, Naudts K, Spencer E, David A. Effects of amisulpride on emotional memory using a dual-process model in healthy male volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0269881108097722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guscott M, Bristow LJ, Hadingham K, Rosahl TW, Beer MS, Stanton JA, Bromidge F, Owens AP, Huscroft I, Myers J, Rupniak NM, Patel S, Whiting PJ, Hutson PH, Fone KC, Biello SM, Kulagowski JJ, McAllister G. Genetic knockout and pharmacological blockade studies of the 5-HT7 receptor suggest therapeutic potential in depression. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund PB, Danielson PE, Thomas EA, Slanina K, Carson MJ, Sutcliffe JG. No hypothermic response to serotonin in 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1375–1380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337340100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund PB, Huitron-Resendiz S, Henriksen SJ, Sutcliffe JG. 5-HT7 receptor inhibition and inactivation induce antidepressantlike behavior and sleep pattern. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund PB, Sutcliffe JG. Functional, molecular and pharmacological advances in 5-HT7 receptor research. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidmann DE, Metcalf MA, Kohen R, Hamblin MW. Four 5-hydroxytryptamine7 (5-HT7) receptor isoforms in human and rat produced by alternative splicing: species differences due to altered intron-exon organization. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1372–1381. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidmann DE, Szot P, Kohen R, Hamblin MW. Function and distribution of three rat 5-hydroxytryptamine7 (5-HT7) receptor isoforms produced by alternative splicing. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1621–1632. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick KA, Lee DC, Hen R, Dulawa SC. Behavioral effects of chronic fluoxetine in BALB/cJ mice do not require adult hippocampal neurogenesis or the serotonin 1A receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:406–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen NH, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Rothman RB, Roth BL. N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine's antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2303–2312. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S, Kramer GL, Zukas PK, Moeller M, Petty F. In vivo biogenic amine efflux in medial prefrontal cortex with imipramine, fluoxetine, and fluvoxamine. Synapse. 1994;18:294–297. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, Lee SH, Lee JH, Yoon BH, Yang SJ, Hwang MY, Yoon JS. Amisulpride versus risperidone in the treatment of depression in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, controlled trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1504–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama M, Fujioka T, Duman RS. Chronic olanzapine or fluoxetine administration increases cell proliferation in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of adult rat. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvachnina E, Liu G, Dityatev A, Renner U, Dumuis A, Richter DW, Dityateva G, Schachner M, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Ponimaskin EG. 5-HT7 receptor is coupled to G alpha subunits of heterotrimeric G12-protein to regulate gene transcription and neuronal morphology. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7821–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1790-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Boyer P, Turjanski S, Rein W. Amisulpride versus imipramine and placebo in dysthymia and major depression. Amisulpride Study Group. J Affect Disord. 1997;43:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Engel RR, Kissling W. Amisulpride, an unusual "atypical" antipsychotic: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:180–190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Baron BM, de Lecea L, Miller JD, Prosser RA, Rea MA, Foye PE, Racke M, Slone AL, Siegel BW, et al. A novel adenylyl cyclase-activating serotonin receptor (5-HT7) implicated in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. Neuron. 1993;11:449–458. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90149-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA. Dopaminergic deficit and the role of amisulpride in the treatment of mood disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17 Suppl 4:S9–S15. discussion S16-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer AM, Joyce E, Balasubramaniam K, Choudhary PC, Saleem PT. Treatment with amisulpride and olanzapine improve neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:445–454. doi: 10.1002/hup.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins UL, Gianutsos G, Eison AS. Effects of antidepressants on 5-HT7 receptor regulation in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:352–367. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandam LS, Jhaveri D, Bartlett P. 5-HT7, neurogenesis and antidepressants: a promising therapeutic axis for treating depression. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:546–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott GE, Rao U, Nuccio I, Lin KM, Poland RE. Effect of bupropion-SR on REM sleep: relationship to antidepressant response. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;165:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Gessa GL. The substituted benzamides and their clinical potential on dysthymia and on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:247–253. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrault G, Depoortere R, Morel E, Sanger DJ, Scatton B. Psychopharmacological profile of amisulpride: an antipsychotic drug with presynaptic D2/D3 dopamine receptor antagonist activity and limbic selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racagni G, Canonico PL, Ravizza L, Pani L, Amore M. Consensus on the use of substituted benzamides in psychiatric patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50:134–143. doi: 10.1159/000079104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL. Drugs and valvular heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:6–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R, Siebert D, Rice KC, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Rothman RB. Salvinorin A: a potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182234399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Craigo SC, Choudhary MS, Uluer A, Monsma FJ, Jr, Shen Y, Meltzer HY, Sibley DR. Binding of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents to 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-hydroxytryptamine-7 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:1403–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:353–359. doi: 10.1038/nrd1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Savage JE, Rauser L, McBride A, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL. Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications. Circulation. 2000;102:2836–2841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, Weisstaub N, Lee J, Duman R, Arancio O, Belzung C, Hen R. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker H, Claustre Y, Fage D, Rouquier L, Chergui K, Curet O, Oblin A, Gonon F, Carter C, Benavides J, Scatton B. Neurochemical characteristics of amisulpride, an atypical dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist with both presynaptic and limbic selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, Sibley DR, Roth BL, Mailman R. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1400–1411. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Jr, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR. Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18200–18204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight AJ, Carolo C, Petit N, Zwingelstein C, Bourson A. Identification of 5-hydroxytryptamine7 receptor binding sites in rat hypothalamus: sensitivity to chronic antidepressant treatment. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeraldi E. Amisulpride versus fluoxetine in patients with dysthymia or major depression in partial remission: a double-blind, comparative study. J Affect Disord. 1998;48:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Carboni E, Frau R, Di Chiara G. Increase of extracellular dopamine in the prefrontal cortex: a trait of drugs with antidepressant potential? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;115:285–288. doi: 10.1007/BF02244785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR, Gittins SA, Collin LL, Middlemiss DN, Riley G, Hagan J, Gloger I, Ellis CE, Forbes IT, Brown AM. Functional characterisation of the human cloned 5-HT7 receptor (long form); antagonist profile of SB-258719. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1300–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR, Melotto S, Massagrande M, Gribble AD, Jeffrey P, Stevens AJ, Deeks NJ, Eddershaw PJ, Fenwick SH, Riley G, Stean T, Scott CM, Hill MJ, Middlemiss DN, Hagan JJ, Price GW, Forbes IT. SB-656104-A, a novel selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, modulates REM sleep in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:705–714. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To ZP, Bonhaus DW, Eglen RM, Jakeman LB. Characterization and distribution of putative 5-ht7 receptors in guinea-pig brain. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesolowska A, Nikiforuk A, Stachowicz K, Tatarczynska E. Effect of the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB 269970 in animal models of anxiety and depression. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel H, Grunder G, Hillert A, Philipp M, Gattaz WF, Sauer H, Adler G, Schroder J, Rein W, Benkert O. Amisulpride versus flupentixol in schizophrenia with predominantly positive symptomatology -- a double-blind controlled study comparing a selective D2-like antagonist to a mixed D1-/D2-like antagonist. The Amisulpride Study Group. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s002130050614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Chen Z, He J, Haimanot S, Li X, Dyck L, Li XM. Synergetic effects of quetiapine and venlafaxine in preventing the chronic restraint stress-induced decrease in cell proliferation and BDNF expression in rat hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2006;16:551–559. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]