Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common, autosomal dominant disorder primarily characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy and is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in youth. HCM is caused by mutations in several sarcomeric proteins, with mutations in MYH7, encoding β-MyHC, being the most common. While many mutations in the globular head region of the protein have been reported and studied, analysis of HCM-causing mutations in the β-MyHC rod domain has not yet been reported. To address this question, we performed an array of biochemical and biophysical assays to determine how the HCM-causing E1356K mutation affects the structure, stability, and function of the β-MyHC rod. Surprisingly, the E1356K mutation appears to thermodynamically destabilize the protein, rather than alter the charge profile know to be essential for muscle filament assembly. This thermodynamic instability appears to be responsible for the decreased ability of the protein to form filaments and may be responsible for the HCM phenotype seen in patients.

Keywords: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cardiac hypertrophy, mutation

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common autosomal dominant disease predominantly characterized by hypertrophy of the left ventricle[1; 2; 3]. The prognosis for HCM is often benign, but a portion of patients die of sudden cardiac death or heart failure, and HCM is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in youth[4]. Mutations in MYH7, the gene encoding β-MyHC, are the most common cause, representing approximately 30% of all HCM cases[5; 6]. While the majority of these mutations are located in the protein’s globular head region, approximately 20% are located in the protein’s long, α-helical coiled-coil rod[7]. Mutations in the myosin rod have been hypothesized to disrupt muscle filament assembly and to cause disease by inducing myofibrillar disarray[7].

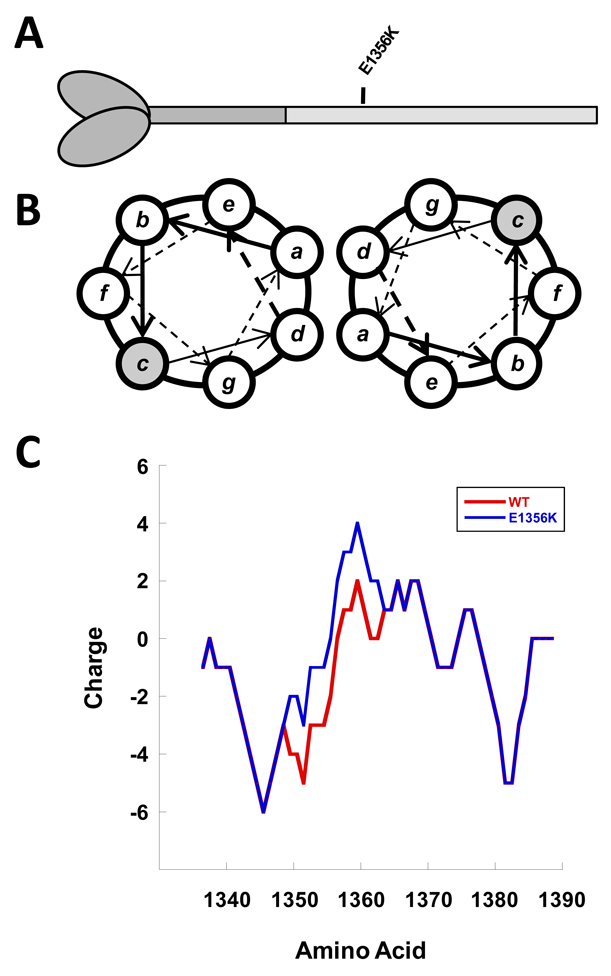

To test this hypothesis, we chose to examine how a mutation associated with HCM affects the structure, stability, and function of the protein[4]. The mutation chosen was E1356K and is located in the C-terminal 700 amino acids of the protein known as LMM (Figure 1A)[4]. Found in the c position of the coiled-coil heptad repeat, this mutation was chosen because it is predicted in silico to have the largest effect of any known mutation on the charge profile of the rod (Figure 1B and 1C) and exhibits extremely high conservation across all sarcomeric myosins. Using a variety of assays previously established for investigating disease-causing mutations in the β-MyHC rod, our data show that, surprisingly, the E1356K mutation causes a thermodynamic destabilization of the protein[8; 9]. It is this protein instability, rather than the charge disruption, which appears to be primarily responsible for the HCM phenotype seen in patients.

Figure 1.

Position of the E1356K mutation in the β-MyHC rod. (A) The globular head and N-terminal segment of the β-MyHC rod are shown in dark gray. The C-terminal LMM segment of the rod is shown in light gray, with the relative position of the E1356K mutation denoted. (B) Relative position of amino acids in the LMM coiled-coil, denoted a–g. The c position in which the E1356K mutation is found is highlighted in gray. (C) Charge profile of the myosin rod. The charge profiles of WT (red) and E1356K (blue) LMM are shown from residues 1340–1390. Mutating E1356 to a lysine causes a net positive shift in charge.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Wild-type β-MyHC LMM (aa residues 1231–1938) was cloned into the pUC18 expression vector and the E1356K mutation was introduced via inverse PCR, verified by sequencing, and subcloned into the pET3a expression vector as described previously (modified pET vector provided by R.Thompson). Constructs were transformed into BL-21 cells and protein extraction and purification were performed as previously described[9]. Briefly, proteins were purified on Ni-NTA agarose, eluted with imidazole, and further purified by anion exchange chromatography. LMM containing fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE for purity, pooled, and concentrated using Amicon Ultracel 50K centrifuge columns.

Circular dichroism measurements

Wild-type and mutant LMM proteins were dialyzed into 10 mM TES, 300 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.3, diluted to approximately 0.3 mg/mL, and reduced with 1 mM TCEP. Circular dichroism (CD) analysis was performed using a J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Inc, Easton, MD) with constant N2 flushing. All measurements were performed at 4 °C with a 1-mm path length optical cell. Spectra were determined from 240 nm to 200 nm with a 0.1 nm data pitch, a continuous scanning speed of 100 nm/min, and averaged over 5 accumulations. Baseline spectra for buffer were collected in the same manner and subtracted from protein spectra. The spectra were normalized by mean residue molar ellipticity and percent α-helix was calculated as previously described[10].

Thermal denaturation monitored by CD222

Protein thermal stability was measured by CD at 222 nm during temperature-induced protein denaturation from 4 °C to 90 °C. Data were collected at 1 °C intervals at a scan rate of 60 °C per hour. To determine transition thermodynamics, the change in mean residue ellipticity as a function of temperature was modeled using a non-linear least squares algorithm that assumes the two-state transition of monomer from a folded to an unfolded state with no change in heat capacity between the folded and unfolded forms[11]. The fraction folded at any given temperature was calculated using a model similar to one which we have previously described, but because the heat capacities of the folded and unfolded states are assumed to be equal, ΔCp was fixed at zero in all models described here[9].

Static Light Scattering

The self-assembly of wild-type and mutant protein was measured in real-time by 90° light scattering using a PTI QM-2000-6SE fluorescence spectrometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) essentially as described previously[9]. Briefly, measurements were taken for buffer without salt (10 mM TES, 3.5 mM EDTA, 1mM TCEP, pH 7.3) for two minutes to obtain a baseline for scattering, at which point an equal volume of 400 nM protein in 10 mM TES, 300 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM EDTA, 1mM TCEP, pH 7.3 was added, diluting the buffer to 150 mM NaCl and allowing for self-assembly at a final protein concentration of 200 nM. Reactions were allowed to proceed to completion (40 minutes) before 5M NaCl was added to return the NaCl concentration to 300 mM. Data were analyzed using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) with background buffer scattering subtracted from each reading.

Paracrystal Formation and Visualization

Paracrystals of wild-type and mutant protein were formed by dialyzing 100 ug of protein into 10 mM bis-Tris propane, 100 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.3, and imaged using a Phillips CM10 TEM at 80 kV as previously described[9].

Results

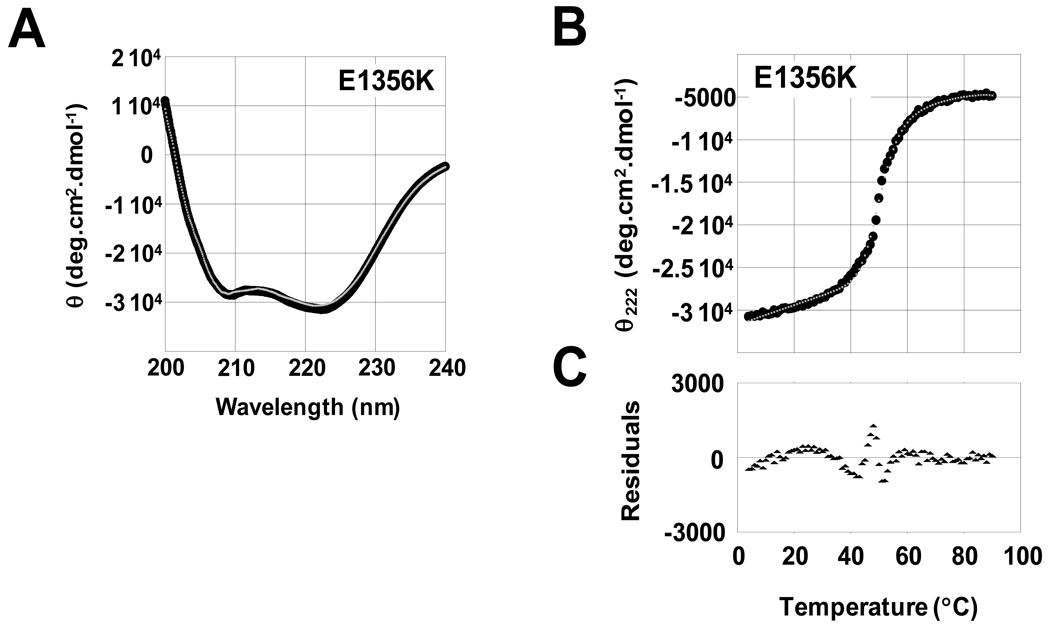

The E1356 residue of LMM is located in the c position of the α-helical heptad repeat. Because amino acids in the c position of LMM are typically responsible for mediating electrostatic interactions between adjacent coiled-coils, we hypothesized the charge reversal associated with the E1356K mutation would destabilize the interactions between coiled-coils but not disrupt the secondary structure of the α-helix. To test this, we obtained far-UV CD spectra for both WT and E1356K LMM to determine secondary structure. Both WT and E1356K protein displayed nearly identical, canonical α-helical spectra, with each showing characteristic minima at 208 nm and 222 nm (Figure 2A, Table 1). E1356K had a calculated α-helical content of 89.1%, similar to the 91.5% α-helix seen for WT LMM, and suggesting E1356K does not have a significant effect on the secondary structure of the protein (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The E1356K mutation alters the thermal stability but not the secondary structure of LMM. (A) Far-UV CD spectra of WT (black) and E1356K (gray) LMM were obtained from 250 nm to 200 nm. WT and E1356K LMM both display nearly identical, canonical a-helical structures, with characteristic minima at 208 nm and 222 nm. (B) The α-helical secondary structure of LMM was monitored by θ222 during thermal denaturation. Measured θ222 data (black) were fit to a theoretical model of protein denaturation (gray) over the range of the thermal transition to derive thermodynamic parameters. (C) Residuals for the fit of the theoretical model to the measure data are calculated as the difference between the two at each point. Residuals are around zero, indicating our model fits well and shows no systematic deviation.

Table 1.

Biophysical data for LMM proteins.

| Construct | [θ]222 | α-Helix | Tm | ΔGapp,37 | ΔH | ΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| deg·cm2·dmol-1 | % | °C | kcal·mol−1 | kcal·mol−1 | kcal·mol−1·K−1 | |

| Wild type | −31,422 | 91.5 | 50.9 | −3.04 | −71.1 | −0.220 |

| E1356K | −30,674 | 89.1 | 50.5 | −2.38 | −57.4 | −0.177 |

Although E1356K LMM appears to be properly folded, the mutation could destabilize the coiled-coil[ 9]. To determine if this is the case, the stability of WT and E1356K LMM was monitored from 4 °C to 90°C and the thermal denaturation of each was modeled to obtain thermodynamic parameters (Figure 2B and 2C, Table 1). E1356K LMM shows a thermal midpoint of unfolding that is decreased by 0.4 °C relative to WT protein, though the thermal stability at physiological temperature is even more telling. E1356K LMM has a ΔΔG at 37 °C of −0.66 kcal·mol−1, and ΔH and ΔS are both decrease by over 19% (Table 1). These results suggest that under physiologically relevant conditions, E1356K LMM is less thermodynamically stable than WT.

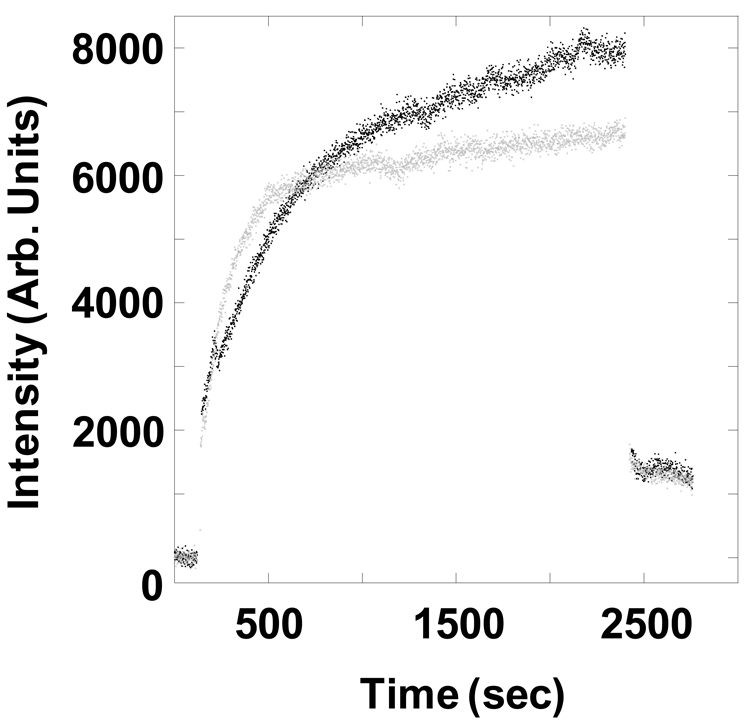

To determine if the decreased stability of E1356K LMM affects the ability of the protein to self-assemble, we utilized static light scattering to follow the process in real time. Both WT and E1356K LMM were diluted from high salt buffer to low salt buffer to initiate filament assembly, and the reaction was monitored by 90° light scattering (Figure 3). The majority of WT LMM assembled within the first 12 minutes, though E1356K LMM did not assemble to the same extent. Initial rates of assembly were similar for both proteins, but after approximately 9 minutes self-assembly of E1356K LMM began to plateau, whereas WT LMM continued to assemble. This difference in late-stage assembly led E1356K LMM to assemble to only approximately 80% of WT LMM.

Figure 3.

E1356K LMM does not form filaments as well as WT LMM in real-time self-assembly assays. The baseline amount of 90° light scattering in no salt buffer was obtained for 120 sec. An equal volume of WT LMM (Black) or E1356K LMM (gray) was then added, diluting the sample to 150 mmol/L NaCl and 200 nmol/L protein to initiate self-assembly. The reaction proceeded for 40 min before the addition of 5 mol/L salt to return the buffer to 300 mmol/L NaCl and demonstrate reversibility. The intensity of 90° light scattering is plotted in arbitrary units with respect to time.

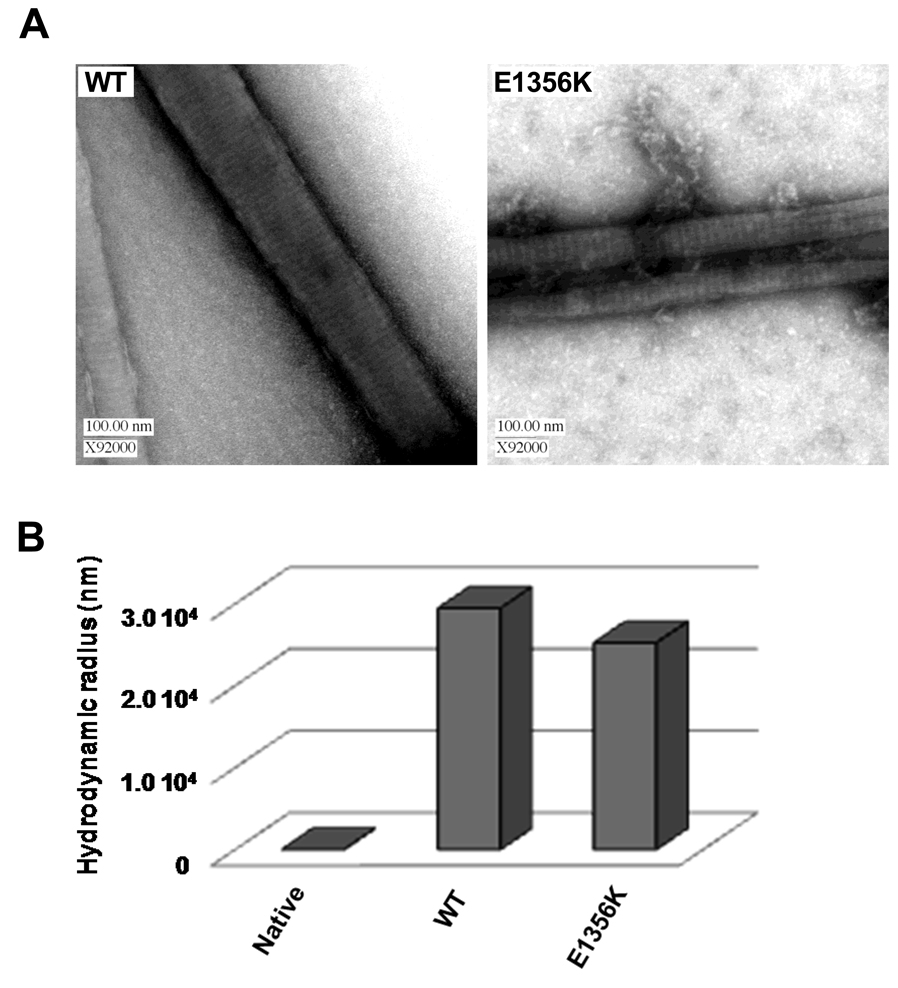

We next sought to determine if the E1356K mutation affects the morphology or structure of protein assemblies by visualizing paracrystals, which are well-ordered assemblies of LMM that provide an established model for thick filament formation. Paracrystals formed from E1356K LMM had a periodicity of 14.4 nm, similar to the 14.0 nm periodicity seen for WT, and the 14.3 nm axial spacing seen for muscle fibers in vivo (Figure 4, Table 2). These differences are not statistically significant, suggesting that packing into filaments is not affected by the E1356K mutation. To further characterize filament morphology, molecular sizing experiments were performed by dynamic light scattering (DLS). DLS showed unassembled protein has a hydrodynamic radius of 22 nm, whereas filaments of WT LMM have hydrodynamic radii of 29,500 nm. E1356K LMM forms filaments with hydrodynamic radii of 25,200 nm, a difference which cannot be confirmed as statistically significant (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Paracrystals formed by E1356K LMM are morphologically indistinguishable from paracrystals formed by WT LMM. (A) WT and E1356K LMM were dialyzed overnight at 4°C a into a low salt crystallization buffer (10 mmol/L bis-Tris propane, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 3.5 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.3) to induce paracrystal formation. Paracrystals were then adsorbed onto carbon mesh grids and electron micrographs were recorded at a magnification of ×92000. Image manipulate software was used to obtain paracrystal periodicity measurements which, to reduce noise, were taken over the range of several striations and divided by the number of striations to obtain an average periodicity per paracrystal. (B) WT and E1356K paracrystals are similar in size. WT and E1356K LMM were self-assembled in a manner similar to 90° light scattering experiments. Reactions were carried out at a final concentration of 150 mmol/L NaCl and 200 nmol/L protein, and were allowed to proceed for 45 minutes at room temperature before molecular sizing experiments were performed. As a control, the hydrodynamic radius of WT LMM was determined prior to assembly and is denoted as native.

Table 2.

LMM paracrystal parameters.

| Construct | Striations (nm) | +/− | n = |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 14.0 | 0.44 | 20 |

| E1356K | 14.4 | 0.68 | 15 |

Discussion

HCM is a common genetic disease, and MYH7 is the gene in which HCM mutations are most often identified. However, despite the fact that mutations in the rod domain of β-MyHC may account for up to 20% of MYH7-related cases of HCM, no characterization of these mutations had been performed [4]. Here we present the first work to understand the pathogenicity of an HCM-causing mutation in the β-MyHC rod using techniques which we have previously utilized to characterize other disease causing mutations in this region of the protein[8; 9]. E1356K was chosen as a model mutation because it is predicted computationally to severely affect the charge distribution governing thick filament assembly. Our data suggest that for this mutation, reversing the charge of a single amino acid will destabilize the protein. This protein cannot form filaments as well as WT protein, and may help explain how this mutation leads to the clinical phenotype present in patients.

As expected, mutating E1356 to lysine did not have any detectable effect on the secondary structure of LMM. Both WT and E1356K LMM display canonical α-helical spectra and have a similar calculated percentage of α-helix. The mutation did, however, affect the stability of the protein. Thermal melts show that E1356K has a decreased Tm compared to WT LMM, a ΔΔG at 37°C of −0.66·kcal mol−1, and a corresponding ΔH and ΔS which are both decreased by nearly 20% from WT. Together, these data suggest that under physiological conditions E1356K LMM is much less stable than WT protein. Amino acids in the heptad c position are thought to be important for forming the ionic interactions between coiled-coils necessary for filament formation. Our data imply that by reversing the charge of an amino acid at this position the protein becomes destabilized, even though we are unable to detect any perturbation to the structure of the individual α-helices.

The destabilization of E1356K LMM appears to have an effect on the protein’s function as well. Results from 90° light scattering show E1356K LMM is able to self-assemble at a rate similar to WT LMM, but the reaction truncates at a level 20% lower than seen with WT protein. Data from molecular sizing experiments show that filaments being formed by E1356K LMM are similar in size to those formed from WT LMM, suggesting that in 90° light scattering experiments, fewer assemblies are being formed rather than smaller assemblies. Electron microscopy of WT and E1356K LMM paracrystals also suggests that E1356K LMM is able to form filaments with normal ultrastructure, as each displays periodicity similar to the expected 14.3 nm.

Our data suggest that the E1356K mutation in β-MyHC causes HCM by destabilizing the coiled-coil. This destabilized protein is then unable to form filaments as well as WT protein (though the filaments that do form appear indistinguishable from WT filaments) which may lead to myofibrillar disarray in vivo. While it is not completely unexpected that altering a charge change in the c position of the LMM coiled-coil could destabilize the dimeric unit, it is surprising that this appears to be the primary molecular phenotype. It should be noted, however, that the change in charge profile could still be responsible for the assembly defect detected by SLS, and that the thermodynamic instability may act cooperatively with this charge-based phenotype to affect the stability of the sarcomere.

An additional possibility is that the E1356K mutation may alter the interaction of LMM with chaperones or myosin rod-associated proteins. While many of the proteins known to interact with the myosin rod, such as MyBP-C, MyBP-H, Myomesin, and Titan, are not thought at present to interact with the E1356K residue, and no chaperones are known to interact with the MyHC tail, much remains to be learned about the ultrastructure of the sarcomere and this is an intriguing hypothesis which cannot be entirely discounted [12; 13; 14].

Although further characterization of this mutation with cell based in situ systems and in vivo models will be necessary to fully dissect how the molecular phenotype seen here leads to disease, and future studies of additional HCM mutations in the rod are warranted, the characterization provided here is an important first step in understanding HCM mutations in the rod region of β-MyHC. Taken together with reports describing β-MyHC rod mutations involved with other diseases such as myosin storage myopathy, MPD1 distal myopathy, and dilated cardiomyopathy, characterization of the E1356K HCM mutation adds to a growing body of data which should lead to a more complete understanding of the pathogenesis associated with mutations in the β-MyHC rod[8; 9].

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Buvoli, R. Thompson, and all members of the L.A.L. laboratory for invaluable discussion and suggestions, and R. Thompson for assistance with SLS assays and protein purification. This work was supported by NIH Grant 5R01 HL085573-01 (to L.A.L.) and NIH Molecular Biophysics Training Grant T32GM065103 (to T.Z.A.)

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- LMM

light meromyosin

- CD

circular dichroism

- SLS

static light scattering

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Carney KP, Lever HM, Lewis JF, Barac I, Casey SA, Sherrid MV. Relationship of race to sudden cardiac death in competitive athletes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:974–980. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308–1320. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92:785–789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Driest SL, Jaeger MA, Ommen SR, Will ML, Gersh BJ, Tajik AJ, Ackerman MJ. Comprehensive analysis of the beta-myosin heavy chain gene in 389 unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burch M, Blair E. The inheritance of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol. 1999;20:313–316. doi: 10.1007/s002469900475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts R, Sigwart U. New concepts in hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, part I. Circulation. 2001;104:2113–2116. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buvoli M, Hamady M, Leinwand LA, Knight R. Bioinformatics assessment of beta-myosin mutations reveals myosin's high sensitivity to mutations. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armel TZ, Leinwand LA. Mutations at the Same Amino Acid in Myosin that Cause Either Skeletal or Cardiac Myopathy Have Distinct Molecular Phenotypes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armel TZ, Leinwand LA. Mutations in the beta-myosin rod cause myosin storage myopathy via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6291–6296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900107106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenfield NJ. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2876–2890. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield NJ. Using circular dichroism collected as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics of protein unfolding and binding interactions. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2527–2535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obermann WM, van der Ven PF, Steiner F, Weber K, Furst DO. Mapping of a myosin-binding domain and a regulatory phosphorylation site in M-protein, a structural protein of the sarcomeric M band. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:829–840. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flashman E, Watkins H, Redwood C. Localization of the binding site of the C-terminal domain of cardiac myosin-binding protein-C on the myosin rod. Biochem J. 2007;401:97–102. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welikson RE, Fischman DA. The C-terminal IgI domains of myosin-binding proteins C and H (MyBP-C and MyBP-H) are both necessary and sufficient for the intracellular crosslinking of sarcomeric myosin in transfected non-muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3517–3526. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]