Abstract

Previous studies using immunohistochemistry suggest that loss of the expression of the prostate-derived Ets transcription factor (PDEF) is a strong indicator for cancer cell malignancy. However, the underlying mechanism for this has not been well elucidated. We determined the role of PDEF in breast cancer cell growth and tumor formation using a series of experiments including Western blotting, promoter-luciferase reporter assay, RNA interference technology and a mouse xenograft model. We also determined the relationship between PDEF expression in human breast tumor specimen and cancer patient survivability. These studies revealed that PDEF expression is inversely associated with survivin expression and breast cancer cell xenograft tumor formation. PDEF-specific shRNA-mediated silencing of PDEF expression resulted in the upregulation of survivin expression in MCF-7 cells, which was associated with increased cell growth and resistance to drug-induced DNA fragmentation (apoptosis). In contrast, survivin-specific siRNA-mediated silencing of survivin expression decreased MCF-7 cell growth. Ectopic expression of PDEF inhibited both survivin promoter activity and endogenous survivin expression. Importantly, shRNA-mediated silencing of PDEF expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells enhanced survivin expression and xenograft tumor formation in vivo. Furthermore, loss of PDEF expression in breast cancer tissues tends to be associated with unfavorable prognosis. These studies provide new information for the role of PDEF and survivin in breast cancer cell growth and tumor formation.

Keywords: PDEF, Survivin, MCF-7, Breast cancer tissues, Xenograft tumor formation

Introduction

Growing evidence suggests that human prostate-derived Ets transcription factor (PDEF) (PDEF/hPSE, human prostate-specific Ets) acts as a tumor suppressor [1–3]. Although human prostate carcinoma cell lines PC-3 and LNCaP express PDEF mRNA, PDEF protein is exclusively expressed in normal prostate glandular epithelial cells [1]. This indicates an important clue that blockade of PDEF protein translation in cancer cells may actually be required for tumor cell malignancy. Immunohistochemical detection of PDEF protein from 19 clinical prostate cancer specimens showed that staining intensities for PDEF in normal glands, hyperplastic glands, and prostate intraepithelial neoplasia lesions are significantly stronger than those in prostate cancer lesions. Moreover, even approximately 30% of prostate cancer lesions display a completely negative staining for PDEF [2]. These authors indicated that negative immunoreactivity for PDEF strongly suggests malignancy, and that decreased immunoreactivities of glands for PDEF could suggest prostate cancer [2]. Similarly, it was also shown that PDEF is highly expressed in normal breast epithelial cells [3]. PDEF protein is reduced in human invasive breast cancer and is absent in invasive breast cancer cell lines [3]. More importantly, adenovirus-mediated ectopic expression of PDEF in breast cancer cells leads to inhibition of invasion, migration, and growth [3]. These observations strongly argue a potential role of PDEF in tumor suppression not only in prostate cancer but also in other cancers such as breast cancer.

While the molecular mechanism for the effects of PDEF in the inhibition of invasion, migration and growth is not fully clear, it is likely that PDEF acts as a transcription factor and modulates the transcription of its downstream specific targeting genes. Survivin, a novel member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein family, has been demonstrated to be involved in promoting tumorigenesis [4], cancer progression, poor disease prognosis, short patient survival and drug/radiation resistance [5, 6]. Here, we report that the survivin gene is a potential downstream target for the PDEF transcription factor. Ectopic expression of PDEF downregulates survivin expression and its promoter activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. In contrast, knockdown of PDEF expression by stable expression of PDEF-specific shRNA results in the upregulation of survivin expression and its promoter activity. More importantly, shRNA-mediated knockdown of PDEF expression in MCF-7 cells increases survivin expression and xenograft tumor formation in vivo, and loss of PDEF expression in breast cancer tissues tends to be associated with unfavorable prognosis. Thus, consideration of both PDEF and survivin may result in better prognosis.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

MCF-7, U937, HeLa, SKBR3, BT-549 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS), 100 units/ml of penicillin and 0.1 μg/ml of streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis of PDEF, survivin and actin expression was performed as previously described [7]. The protein concentration of cell lysates was determined using a BCA kit (Pierce). PDEF antibody was generated in this study (see below) and diluted to 1000×. Survivin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-10811) and diluted to 500×. Actin antibody was from Sigma (A2066) and diluted to 5000×. Signals were detected using a HRPL kit (National Diagnostics/LPS, Rochester, NY) or a Chemo-luminescent Reagent Plus kit (Perkin Elmer) and visualized by autoradiography after various exposure times (usually 20–120 s).

Tissue procurement, isolation of RNA and RT-PCR

Human breast tissues were obtained from the tissue bank facility at Roswell Park Cancer Institute through an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol. The characteristics of the tissues used for RNA isolation are summarized in Table 1. Tumor samples grouped on the basis of histology and stage of each tumor were classified according to WHO criteria. To preserve the quality of RNA, corresponding adjacent normal and tumor tissue specimens from individual patients obtained from surgery were immediately immersed in the “RNA later” solution (Ambion, Austin, TX). Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues using Tri Reagent™ (MRC Inc., Cincinnati, OH) as previous described [8, 9]. To test the quality of RNA, 5 μg of isolated total RNA from each samples was separated through a 1% agarose gel containing 0.45 M formaldehyde. Intact bands for 18S and 28S rRNAs without degradation were used as a criterion for assessing the quality of isolated total RNAs from human breast cancer tissues and cell lines (Fig. 2B). The percentage of tumor vs. normal tissue and epithelial vs. stromal cell population in each tumor tissues was not determined. The mRNA expression for PDEF, survivin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was determined using a one-step RT PCR kit (Qiagen) as previously described [9]. The primers used for RT-PCR were: 5′-ATG GGC AGC GCC AGC CCG GGT C-3′(forward) and 5′-TCA GAT GGG GTG CAC GAA CTG GT-3′(reverse) for PDEF PCR products (1008 bp), 5′-GAG GCT GGC TTC ATC CAC TG-3′(forward) and 5′-CAG CTG CTC GAT GGC ACG GC-3′(reverse) for survivin PCR products (299 bp), and 5′-GCT TCC CGT TCT CAG CCT TGA C-3′(forward) and 5′-ATG GGA AGG TGA AGG TCG GAG-3′(reverse) for GAPDH PCR products (195 bp, internal control).

Table 1.

Characteristics of breast cancer patients and the corresponding cancer tissues

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Available patients | 27 |

| Age (median/range) | 43 (32–92) |

| AJCC Stage Group | PDEF positive |

| I | 3/4 (75%) |

| IIA | 2/3 (66%) |

| IIB | 11/12 (92%) |

| IIIA | 2/2 (100%) |

| IIIB | 2/4 (50%) |

| Unknown | 1/2 (50%) |

| Histopathology | PDEF positive |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 15/18 (83%) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 4/5 (80%) |

| Invasive ductal and lobular carcinoma | 2/2 (100%) |

| Unknown | 0/2 (0%) |

| Overall PDEF status | |

| PDEF positive | 21 (77.7%) |

| PDEF negative | 6 (22.2%) |

| Overall survival by PDEF status | |

| PDEF positive, dead of disease | 0 |

| PDEF negative, dead of disease | 4 (66.6%) |

| Recurrence by PDEF status | |

| PDEF positive and no recurrent | 17 (80.9%) |

| PDEF negative and no recurrent | 1 (16.6 %) |

Fig. 2.

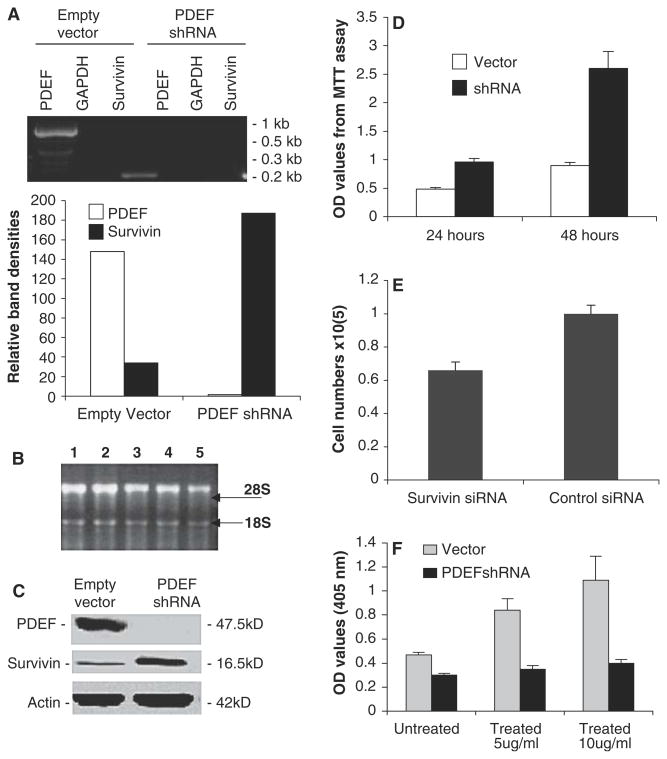

Knockdown of PDEF expression upregulates the expression of survivin. (A) Upper panel: The RT-PCR-determined mRNA expression of PDEF, survivin and GAPDH (internal RT-PCR control) with or without PDEF-specific shRNA silencing of PDEF is shown. Lower panel: The histogram was derived from densitometry of the result in “upper panel” and shows the relative expression of PDEF and survivin after normalization to GAPDH internal controls (lanes 2 & 5). (B) Verification of the quality of total mRNA isolated from breast tumor tissues (lanes 1–3), MCF-7 (Lane 4) and U937 (lane 5). (C) Western blots show the silencing of PDEF expression upregulates survivin protein. Actin expression is an internal protein loading control. Note: Only survivin was detected in (A) and (C) since the other isoforms were expressed at significantly lower levels in these cells. (D) ShRNA-mediated silencing of PDEF inhibits MCF-7 cell growth, which was determined by MTT assay experiments. (E) Silencing of survivin expression (about 60% decrease, not shown) using survivin mRNA-specific siRNA [SRi-2, GCG CCU GCA CCC CGG AGC G [10]] inhibits MCF-7 cell growth determined by counting cell numbers. (F) Knockdown of PDEF showed resistance to cisplatin-induced DNA fragmentation. Note: Each bar in (D), (E) and (F) is the mean ± SD derived from two or three independent experiments. Their p values are less than 0.05

Generation of PDEF small hairpin RNAs (shRNA) and PDEF shRNA stable MCF-7 cell transfectants

A DNA sequence of 21 nucleotides (underlined) in the coding region of PDEF mRNA, which matched the optimal siRNA criteria in an algorithmic program from InvivoGene (San Diego, CA), was selected to design the PDEF shRNA gene. The shRNA gene containing the 21 nucleotide DNA sequence was: 5′-TCC CAC CTG GAC ATC TGG AAG TCA GTC AAG AGC TGA CTT CCA GAT GTC CAG GTT T-3′(sense) and 5′-CAA AAA ACC TGG ACA TCT GGA AGT CAG CTC TTG ACT GAC TTC CAG ATG TCC AGG T-3′(antisense). The above two synthesized DNA sequences were annealed as previous described [10] and directly cloned into psiRNA-hH1zeo Vector (InvivoGen) at the BbsI site to generate the pPDEF-shRNA expression vector, which was confirmed by sequencing. MCF-7 cells (70–80% confluence) in six-well plates were transfected with 5 μg pPDEF-siRNA or psiRNA-hH1zeo (negative control) in serum-free medium using Lipofectamine™ 2000 Plus according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Invitrogen). Stable transfectants were selected with Zeocin (500 μg/ml). After drug selection, 10 individual clones were evaluated by both RT-PCR and western blots. When multiple clones were tested, it was found that clones with less silencing of PDEF only resulted in a minimal upregulation of survivin. We selected the clone demonstrating the most effect on PDEF protein level for the studies.

MTT assay for cell growth

MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay (or directly counting cell numbers) was used to determine cell growth as we previously described [8]. The assay is based on the conversion of the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. Thus, this method provides a quantitative determination of viable cells. Equal cells with or without transfection were seeded in the 96-well plates in triplicate at a density designed to reach sub-confluence at the time of assay. Wells with medium alone were considered as blank. At 24 and 48 h after seeding, 10 μl of MTT was added to each well of cells including the corresponding controls and the plate was incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The MTT crystals from both attached and floating cells were solubilized in 100 μl of 10% SDS and subjected to centrifugation to pellet the cellular debris. Spectrophotometric absorbance from each sample was measured at 570 nm using an ultra Microplate Reader.

PDEF cDNA cloning

The full-length PDEF open reading frame [11] was amplified from normal prostate tissue mRNA by RT-PCR using the two PDEF primers described above, and subsequently cloned into the pcDNA3.1/v5-His TOPO (Invitrogen). The PDEF cDNA sequence in the resulting pcDNA3.1-PDEF expression vector was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing.

Transfection and luciferase assay

HeLa, MDA-MB-231, BT-549 or MCF-7 cells in each well were cotransfected by the survivin promoter-luciferase construct (pLuc-6270 or pLuc-2840) characterized previously [12] along with the PDEF expression vectors (pcDNA3.1-PDEF) or the control vector (pcDNA3.1). Cells were lysed 36–48 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was assessed using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Detailed transfection and luciferase activity assays were performed as previously described [13].

PDEF-fused protein preparation and its antibody generation

The N-terminal segment of PDEF cDNA (GenBank accession no. NM01239) coding amino acid 1–104 was generated by PCR amplification. The amplified PCR product was cleaved with Nde1 and ligated into the pET15b expression vector (Novagen) at the Nde1 site. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5αMCR, and the correct clone was identified by restriction enzyme digestion, followed by sequencing confirmation. For protein expression, E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed by the recombinant plasmid was induced by 1 mM IPTG. PDEF protein was purified from bacterial cell lysates by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA column. The purified PDEF protein was used as antigen for antibody production in rabbits. Two young adult New Zealand white rabbits were immunized with purified N-terminal 1–104 peptide of PDEF protein that does not have homology to other Ets factors. Anti-sera were purified by affinity column following the manufacture’s instruction (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Specificity of this antibody was demonstrated by Western blots using cell lysates from PDEF positive (MCF-7[3]) and negative (Skbr3[3], HeLa and U-937[11]) cells as well as PDEF protein (additional positive control) (Fig. 1A, upper panel). The result from Western blot analysis is generally consistent with PDEF mRNA expression determined by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 1A, lower panel).

Fig. 1.

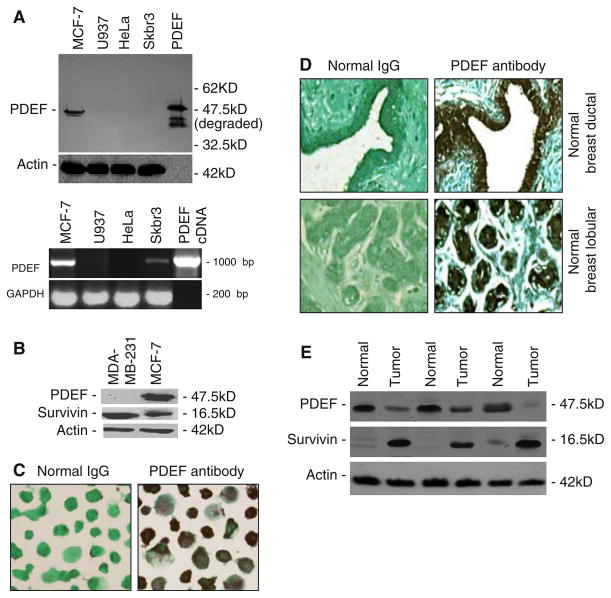

Survivin expression is inversely associated with PDEF protein expression. (A) Upper panel: Western blots show PDEF polyclonal antibodies (see Method section) specifically recognized a PDEF protein band from MCF-7 cell lysates but not from the lysates of U937, HeLa and Skbr3 cells. Lanes 1–4: 50 μg of cell lysates per lane, lane 5: 0.1 ng of purified PDEF protein (positive control). Lower panel: PDEF mRNA expression in the same cell lines determined by RT-PCR. GAPDH is an internal control, and template in the lane 5 is 10 ng pcDNA3.1-PDEF plasmid. (B) Inverse expression pattern of PDEF and survivin in breast cancer cell lines. The expression of PDEF, survivin and actin was determined by Western blot analysis. Only the major survivin isoform was detected as the other isoforms are expressed at significantly lower levels in these cells. (C) Immunocytochemistry confirms PDEF expression in MCF-7 cells (400× magnification). (D) Immunohistochemistry showed PDEF expression in ductal and lobular epithelial cells of normal breast tissues (E). Inverse expression pattern of PDEF and survivin in normal and cancerous breast tissues. Protein expression was determined as in (B). Note: Actin expression shown in (A), (B) and (E) was used as a total protein loading control

DNA fragmentation cell death detection

DNA fragmentation assay was performed using a Cell Death Detection ELISA assay kit (Rohe, Indianapolis, IN) as previously described [8]. Elisa results were measured at 405 nm using an ultra Microplate reader.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

The adjacent normal breast tissues used in IHC were obtained from the Translational Research Tissue Support Resource of Pathology, Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) and inspected by a pathologist. The IHC study was performed in pathology laboratory following the Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol. Fourteen recently diagnosed breast carcinomas were selected for immunohistochemical staining. The tissue sections examined contained both infiltrating tumor and adjacent normal tissue. Of these tumors, six were Bloom Richardson Grade (BRG) 1, two were BRG 2 and six were BRG 3. All the specimens were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Deparaffinized tissue sections were rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% H2O2 for 10 min. Specimens on slides were microwaved in citrate buffer antigen retrieval solution (Vector Laboratories) twice for 5 min each and washed with PBS for 5 min. Slides were blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min and incubated for over night with PDEF antibody diluted in PBS (1:100). The slides were washed with PBS three times for 5 min each, incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit diluted in 1:100 in PBS contain 1.5% normal goat serum) for 30 min. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method (ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). A positive reaction was detected using 3, 3-diaminobezidine (DAB) (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with light green. The cells with nuclear PDEF staining were considered as immunohistochemically positive. Tumors were graded using a Bloom-Richardson grading system. The average nuclear staining intensity of PDEF staining versus tumor grads was compared with that of normal breast tissues present in the same section and evaluated as strong, moderate, week, and negative. No staining was observed with negative control samples (absence of primary antibody or incubation with normal rabbit IgG). Immunocytochemistry was performed similar to IHC with the exception that resuspended MCF7 cells in the 10% formaldehyde solution at the density of 1 × 106/ml were fixed on slides.

MCF-7 cell xenograft tumor formation in SCID mice

The MCF-7 cells stably transfected with either the control vector (psiRNA) or the pPDEF-shRNA expression vector were used in this study. Six week-old female SCID mice, obtained from Animal facility of Roswell Park Cancer Institute, were subcutaneously injected at the right flank of the back region of mice with 5 × 106 MCF-7 cells per injection in PBS buffers. Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment and observed for xenograft tumor formation over 12-week periods. During the experiment, the mice were examined weekly. Tumor sizes were measured as follows: Tumor length (L) and width (W) were measured using a vernier caliper. The tumor volume (V) was calculated by formula: V = 0.4(L × W2). Mice were scarified before a tumor mass reached 2 cm in the longest diameter. Selected tumors were isolated from scarified mice and immediately preserved in RNA later solution (Ambion) for future analyses. The experiment was performed in accordance with a mouse protocol, which was reviewed and approved by the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Statistical analysis of experimental data

A “t-test” was used for analysis of the significance, and significance (p value) was set at the normal level of 0.05 or less. A log-rank test was used to evaluate the significance in tumor formation differences between the PDEF-silencing xenograft group and the control cell xenograft group [14]. The Kaplan–Meir method was used for calculating survivability and the construction of survival graphs [15].

Results

Expression of PDEF protein is inversely associated with survivin expression and breast cancer cell malignancy

The specificity of PDEF polyclonal antibodies was characterized by Western blots with PDEF positive and negative cells as well as PDEF protein as shown (Fig. 1A, upper panel), which is generally consistent with the mRNA expression in these cells determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A, lower panel). However, as previously reported that PDEF mRNA expression may not represent PDEF protein expression [1], a low PDEF mRNA but not protein was found in Skbr3 breast cancer cells (Fig. 1A, lower panel). The xenograft tumor-take-rate for MCF-7 cells is approximately 20% (Ling and Li, unpublished observation) and for MDA-MB-231 cells is 100% in the absence of estrogen in SCID mice [16]. Western blots indicated that MDA-MB-231 cells highly express survivin without the expression of PDEF (Fig. 1B). In contrast, MCF-7 cells express PDEF protein with much reduced survivin expression (Fig. 1B). The expression of PDEF in MCF-7 cells was further confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1C). Importantly, while survivin was undetectable (not shown) or with a very low level in normal breast tissues [5], we found that PDEF is highly expressed in both ductal and lobular epithelial cells within normal breast tissues (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the expression of PDEF protein was markedly reduced in breast tumor tissues while survivin expression was significantly increased (Fig. 1E). These observations suggest that PDEF expression may downregulate the expression of survivin, and loss of PDEF expression with the upregulation of survivin may contribute to cancer cell growth.

Silencing of PDEF expression by stable expression of PDEF shRNA upregulates survivin expression

To corroborate whether PDEF negatively regulated survivin expression, we employed the PDEF-specific shRNA approach to silence PDEF expression. MCF-7 cells were stably transfected with either the control vector or the PDEF shRNA expression vector. Individual clones were selected on the basis of silenced PDEF and increased survivin expression profiles determined by RT-PCR and Western blots. Consistent with the finding shown in Fig. 1, stable expression of the PDEF shRNA blocked PDEF expression and accordingly upregulated survivin mRNA as compared with corresponding controls (Fig. 2A). The total mRNA quality was confirmed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 2B) Importantly, silencing of PDEF expression subsequently resulted in the upregulation of survivin (Fig. 2C), which was associated with increased cell growth determined by MTT assay as compared with the control (Fig. 2D). In contrast, survivin-specific siRNA-mediated silencing of survivin expression [10] decreased MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth (Fig. 2E). More importantly, cells with the silencing of PDEF expression resisted cisplatin-induced apoptosis (DNA fragmentation, Fig. 2F). These results suggest an opposing functional relationship between PDEF and survivin as well as the survivin gene may be a downstream target for PDEF.

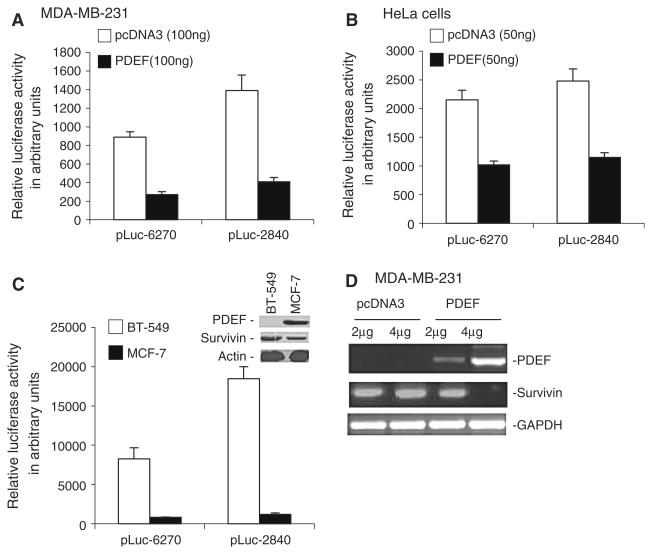

Ectopic expression of PDEF downregulates survivin promoter activity and endogenous survivin expression

Next, we hypothesized that if PDEF-mediated inhibition of survivin involves decreased survivin transcription, forced expression of PDEF should downregulate survivin promoter activity, and that survivin promoter activity should be much higher in PDEF-negative cell lines than in PDEF-positive ones. Consistent with this hypothesis, ectopic expression of PDEF in the PDEF-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 3A) as well as in carcinoma HeLa (Fig. 3B) cells inhibited survivin promoter-driven luciferase activity. Consistent with the fact that BT-549 breast cancer cells are PDEF-negative and MCF-7 cells are PDEF-positive (Fig. 3C, inset), survivin promoter-luciferase reporter assay experiments indicated that survivin promoter-driven luciferase activity was much higher in BT-549 cells than in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3C). Importantly, ectopic expression of PDEF also downregulated endogenous survivin expression (Fig. 3D). Although out of the main focus of this study, the molecular mechanism by which PDEF downregulates survivin transcription warrants further investigation, (see Discussion).

Fig. 3.

PDEF downregulates survivin promoter activity not only in breast but also in non-breast cancer cells. (A, B) Luciferase assays show that ectopic expression of PDEF in PDEF-negative MDA-MB-231 (A) or HeLa (B) cells downregulated survivin promoter activity. (C) Luciferase assays show that survivin promoter activity is much higher in the PDEF-negative BT-549 cells than in the PDEF-positive MCF-7 cells. Inset shows the expression of PDEF, survivin and Actin (loading control) in Western blots. Note: the pLuc empty vector negative control and the CMW-driven luciferase positive control were omitted in (A), (B) and (C) for conciseness. (D) Western blots show that ectopic expression of PDEF inhibited endogenous survivin expression. Note: Data bars in (A), (B) and (C) are means ± SD derived from 2–4 independent assays. The p values in (A), (B) and (C) are less than 0.001

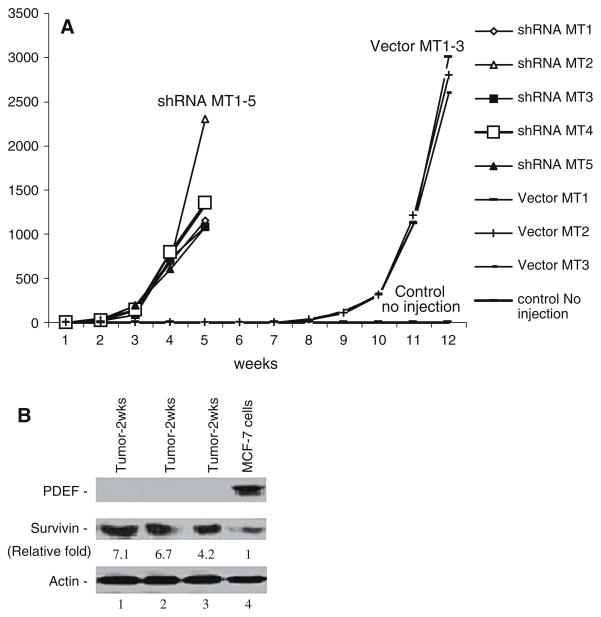

Silencing of PDEF expression by PDEF-specific shRNA in MCF-7 cells upregulates survivin and promotes xenograft tumor formation in SCID mice

To gain insights into the potential negative role of PDEF expression in tumorigenesis in vivo, we performed xenograft experiments in SCID mouse using MCF-7 cells in which PDEF expression was permanently silenced by the stable expression of PDEF-specific shRNA (Fig. 2). MCF-7 cells, which stably expressed either control vectors or PDEF shRNA expression vectors, were injected into SCID mice (see Materials and methods), respectively. The xenograft tumor formation was observed over a 12-week period after injection. As shown in Fig. 4A and Table 2, silencing of PDEF expression strikingly accelerated xenograft tumor formation as compared with the control vector-transfected cells (p value = 0.00184). We further analyzed by Western blots the expression of PDEF and survivin in some of PDEF-silencing xenografts isolated from SCID mice (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the cell-based in vitro results that PDEF downregulated survivin expression and promoter activity, the data from xenograft tumors showed that loss of PDEF expression is associated with increased expression of survivin as compared with the control cells before injection (Fig. 4B). These observations suggest that upregulation of survivin resulted from the loss of PDEF may contributes to xenograft tumor formation in vivo and agues that loss of PDEF is required for xenograft tumor growth.

Fig. 4.

Effects of silencing of PDEF on tumor formation and survivin expression in vivo. (A) Silencing of PDEF expression accelerates MCF-7 xenograft tumor formation. MCF-7 cells with permanent expression of PDEF shRNAs or empty vector controls were injected into mice and observed for tumor formation as described in the Method section. (B) Silencing of PDEF expression upregulates the expression of survivin. Expression of PDEF, survivin and actin (internal loading control) in the isolated xenografts were determined by Western blots. Lanes 1–3: 50 μg/lane of xenograft tumor lysates. Lane 4: 50 μg of MCF-7 cell lysates transfected with vector before injection. The relative expression level of survivin was quantitated using the Personal Densitometer SI and ImageQuant5.2 Software (Molecular Dynamics) and shown after normalized to actin (set control as 1).

Table 2.

Silencing of PDEF expression promotes xenograft tumor formation in SCID mice

| Cell lines | Mouse numbers for xenograft experiments | Mouse numbers with tumor development | Mouse numbers without tumor development |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 with PDEF shRNA expression | 5 | 5 (2–3 weeks) | 0 |

| MCF-7 with empty vector expression | 5 | 0 (within 7 weeks) | 5 (within 7 weeks) |

| 3 (8 weeks) | 2 (8 weeks) | ||

| No injection | 10 | 0 (8 weeks) | 10 (8 weeks) |

Expression of PDEF in breast cancer tissues tends to be associated with good prognosis and clinical outcome for breast cancer patients

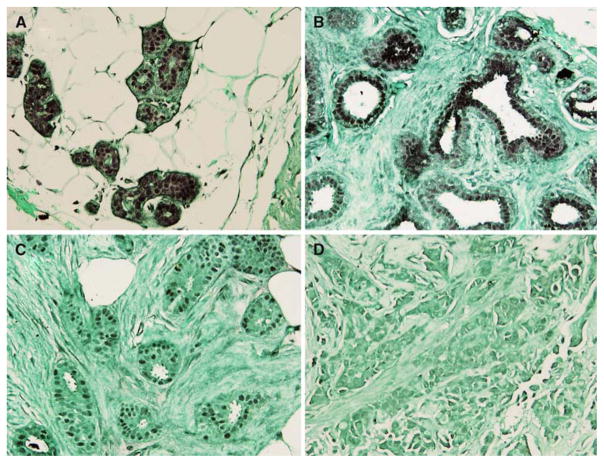

We further evaluated the association of clinical outcome of 27 breast cancer patients with PDEF expression determined by one-step RT-PCR in the primary tumors. As shown in Table 1, 21/27 tumors expressed PDEF. None of these patients died. In contrast, among the six with PDEF-negative tumors, four (66.6%) of the patients died of disease. Additionally, there is a trend towards a negative correlation between PDEF expression and disease progression/recurrence (Table 1). However, due to the small sample size, the result from the Kaplan–Meir analysis of patient survivability was not significant (not shown). We next investigated the expression of the PDEF protein in 14 recently diagnosed breast infiltrating carcinomas and the corresponding adjacent normal breast specimens by immunohistochemical staining. Of these tumors six were Bloom Richardson Grade (BRG) 1, two were BRG 2 and six were BRG 3. In each case, the normal mammary ducts and terminal ductal-lobular units showed strong nuclear expression of the PDEF protein (Fig. 5A, B). In contrast, the infiltrating tumor cells in each case showed decreased or negative PDEF expression (Fig. 5C, D). The percentage of loss of PDEF expression appeared to be increased in the higher BRG tumors (3/6, 50%) as compared with the lower BRG tumors (0/6 0%, Table 3).

Fig. 5.

PDEF protein expression is reduced or negative in invasive breast cancer as compared with normal breast tissue. PDEF immunohistochemical staining showed strong nuclear immunoreactivity in lobular (A) and ductal (B) epithelial cells. An example showed very weak PDEF expression in the well differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinomas (C). An example of poorly differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinomas showed a complete loss of PDEF staining (D). All images are shown at 200× of the original magnifications

Table 3.

Intensity of PDEF staining versus tumor grades

| PDEF staining | BRG 1 | BRG 2 | BRG 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 0/6 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| Weak | 2/6 (33.3%) | 1/2 (50%) | 1/6 (16.6%) |

| Moderate | 3/6 (50%) | 1/2 (50%) | 1/6 (16.6%) |

| Strong | 1/6 (16.6%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/6 (16.6%) |

Discussion

Ets family transcription factors function as transcriptional activators or repressors by binding to the “GGAA/T” DNA motif of target genes which play important roles in development, angiogenesis, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, transformation and tumor invasion [17, 18]. PDEF is a unique member in the Ets protein family and was cloned from human [11] and mouse [19] in 2000. It was found that, although both normal epithelial cells (in the prostate, colon and breast) and cancer cells express PDEF mRNA, PDEF protein is largely expressed in normal epithelial cells [1, 3]. Thus, exclusively looking at the PDEF mRNA expression in cancer may not reflect the real expression of PDEF protein. Nevertheless, PDEF protein tends to be either reduced or lost during cell malignancy and cancer progression [2, 3]. Here, we should point out that a recent study reported a positive role of PDEF in cell migration [20]. The authors also showed that PDEF mRNA (protein not determined in this study) is overexpressed in breast cancer tissues in comparison with PDEF mRNA in normal breast tissues. Nevertheless, our studies revealed that PDEF protein is highly expression in the epithelial cells of normal breast tissues (Figs. 1D, 5A, B), which is consistent with the highly expression of PDEF mRNA in normal breast, colon and prostate tissues shown previously [3]. PDEF protein tends to be reduced or lost during breast cancer progression (Fig. 5C, D and Table 3).

In this report, our data revealed that (1) PDEF is expressed at high levels in normal breast tissues whereas it is downregulated in tumors and its expression tends to be lost in invasive carcinomas; (2) the expression of PDEF protein in MCF-7 breast cancer cells negatively regulated the expression of survivin and its promoter activity, and (3) the upregulation of survivin resulted from the silencing of PDEF increases MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth in vitro (which is inhibited by silencing of survivin expression) and xenograft tumor formation in vivo. These findings are consistent with the function of survivin in promoting tumorigenesis [4] and cancer progression [5], while inhibition of survivin expression or function blocks xenograft tumor formation [21, 22]. As a note, although our experiments revealed that higher expression of PDEF in normal breast tissues and lower or no expression of PDEF in breast tumor tissues (Fig. 5) were inversely associated with the expression of survivin (Fig. 1E), exceptional examples selected from the highest PDEF expression in a particular individual breast tumor tissue and the lowest PDEF expression in a particular individual normal breast tissue may not well match the inverse association with the expression of survivin. This may result from the fact that survivin is usually negative in normal tissues regardless of the expression level changes of PDEF, which suggests that the silence of survivin expression in normal adult tissues is attributed to a more complex reason than PDEF expression. Here, we should also point out that although we have demonstrated in this report that PDEF down-regulates survivin expression and promoter activity, additional experiments will be required for delineation of the molecular mechanism by which PDEF downregulates survivin transcription.

Regardless of the molecular mechanism for PDEF-mediated inhibition of survivin transcription, we have provided additional clinical data in this report to support a potential role for PDEF in the suppression of tumor cell growth and xenograft formation in vivo. Previous studies revealed that many types of cancer including breast cancer express a high level of PDEF mRNA [9, 23–25]. However, it has been shown that although both normal epithelial cells and cancer cells express PDEF mRNA, PDEF protein may not be expressed in epithelial cell-derived cancer tissues [1, 3]. Thus, PDEF mRNA expression in cancer may not reflect the expression of PDEF protein. Since the role of PDEF in clinical outcome is currently unknown, in this report we have analyzed a small cohort of clinical tumor specimens at both PDEF mRNA and protein level. Although the result from analyses of patient survivability was not shown to be significant, the overall information obtained from the analysis of these clinical specimens indicates that the expression of PDEF protein tends to be associated with good prognosis. Further studies using a large cohort of clinical specimen will be required. As a note, we have observed the positive staining of PDEF in non-nuclei of the cell in normal breast tissues (Fig. 5) and occasionally in breast cancer tissues as well. We believe that the non-nuclear staining of PDEF reflects the cytoplasmic pool of PDEF expression. However, the significance for this pool of PDEF is currently unknown. However, since the known function of PDEF is acting as a transcription factor in the cell nuclei, the cytoplasmic pool of PDEF appears to be the transcriptionally non-functional PDEF and may represent the stored PDEF for use in the nuclei when needed. To confirm the major expression of PDEF in nuclei, we fractionated cell lysates into cytoplasmic and nuclear factions using a nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Pierce), and followed by Western blot analysis. The experiment showed that approximate 90% of PDEF is enriched in the nuclear fraction and about 10% in the cytoplasmic fraction.

In sum, we have, for the first time, demonstrated that PDEF downregulates survivin expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Silencing of PDEF expression upregulated the expression of survivin, increased cancer cell growth, resisted drug-induced cell death in vitro and promoted xenograft tumor formation in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Brian Bundy for helping with the statistical analyses of the experimental data in this study, Dr. Stephen Edge for clinical information and Dr. Ashwani Sood for his generous helping in the study. This work was sponsored in part by NIH R01 Grants (CA109481), The Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (BCTR63806) and Grants from Concern Foundation (Beverly Hill, CA) to FL, and shared resources of an NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant (CA16056) to Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- PDEF/hPSE

Prostate derived Ets transcription factor/human prostate-specific Ets

- IAP

Inhibitor of apoptosis

- SCID

Severe combined immunodeficiency

- ShRNA

Small hairpin RNA

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription-mediated polymerase chain reaction

- SD

Standard deviation

References

- 1.Nozawa M, Yomogida K, Kanno N, Nonomura N, Miki T, Okuyama A, Nishimune Y, Nozaki M. Prostate-specific transcription factor hPSE is translated only in normal prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60(5):1348–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsujimoto Y, Nonomura N, Takayama H, Yomogida K, Nozawa M, Nishimura K, Okuyama A, Nozaki M, Aozasa K. Utility of immunohistochemical detection of prostate-specific Ets for the diagnosis of benign and malignant prostatic epithelial lesions. Int J Urol. 2002;9(3):167–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman RJ, Sementchenko VI, Gayed M, Fraig MM, Watson DK. Pdef expression in human breast cancer is correlated with invasive potential and altered gene expression. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4626–4631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F. Role of survivin and its splice variants in tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(2):212–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F. Survivin Study: what is the next wave? J Cell Physiol. 2003;197(1):8–29. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li F, Ling X. Survivin Study: An update of “What is the next wave? J Cell Physiol. 2006;208(3):476–486. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling X, Bernacki RJ, Brattain MG, Li F. Induction of survivin expression by taxol (paclitaxel) is an early event which is independent on taxol-mediated G2/M arrest. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15196–15203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling X, Yang J, Tan D, Ramnath N, Younis T, Bundy BN, Slocum HK, Yang L, Zhou M, Li F. Differential expression of survivin-2B and survivin-DeltaEx3 is inversely associated with disease relapse and patient survival in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2005;49:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghadersohi A, Sood AK. Prostate epithelium-derived Ets transcription factor mRNA is overexpressed in human breast tumors and is a candidate breast tumor marker and a breast tumor antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(9):2731–2738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling X, Li F. Silencing of antiapoptotic survivin gene by multiple approaches of RNA interference technology. BioTechniques. 2004;36(3):450–454. 456–460. doi: 10.2144/04363RR01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oettgen P, Finger E, Sun Z, Akbarali Y, Thamrongsak U, Boltax J, Grall F, Dube A, Weiss A, Brown L, et al. PDEF, a novel prostate epithelium-specific ets transcription factor, interacts with the androgen receptor and activates prostate-specific antigen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(2):1216–1225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Altieri DC. Transcriptional analysis of human survivin gene expression. Biochem J. 1999;344(Pt 2):305–311. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3440305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Ling X, Pan D, Apontes P, Song L, Liang P, Altieri DC, Beerman T, Li F. Molecular mechanism of inhibition of survivin transcription by the GC-rich sequence selective DNA-binding antitumor agent, hedamycin: evidence of survivin downregulation associated with drug sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9745–9751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409350200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, Mantel N, McPherson K, Peto J, Smith PG. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35(1):1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Sun Y, Chen HC, Kung HF, Murphy WJ. Inhibition of MDA-MB-231 human breast tumor xenografts and HER2 expression by anti-tumor agents GAP31 and MAP30. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(2A):653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sementchenko VI, Watson DK. Ets target genes: past, present and future. Oncogene. 2000;19(55):6533–6548. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman RJ, Sementchenko VI, Watson DK. The epithelial-specific Ets factors occupy a unique position in defining epithelial proliferation, differentiation and carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2003;23(3A):2125–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada N, Tamai Y, Miyamoto H, Nozaki M. Cloning and expression of the mouse Pse gene encoding a novel Ets family member. Gene. 2000;241(2):267–274. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunawardane RN, Sgroi DC, Wrobel CN, Koh E, Daley GQ, Brugge JS. Novel role for PDEF in epithelial cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11572–11580. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor DS, Wall NR, Porter AC, Altieri DC. A p34(cdc2) survival checkpoint in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(1):43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall NR, O’Connor DS, Plescia J, Pommier Y, Altieri DC. Suppression of survivin phosphorylation on Thr34 by flavopiridol enhances tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63(1):230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghadersohi A, Odunsi K, Lele S, Collins Y, Greco WR, Winston J, Liang P, Sood AK. Prostate derived Ets transcription factor shows better tumor-association than other cancer-associated molecules. Oncol Rep. 2004;11(2):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galang CK, Muller WJ, Foos G, Oshima RG, Hauser CA. Changes in the expression of many Ets family transcription factors and of potential target genes in normal mammary tissue and tumors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(12):11281–11292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson HG, Harris JW, Wold BJ, Lin F, Brody JP. p62 overexpression in breast tumors and regulation by prostate-derived Ets factor in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(15):2322–2333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]