Abstract

Androgens are thought to cause prostate cancer, but there is little epidemiological support for this notion. Animal studies, however, demonstrate that androgens are very strong tumor promotors for prostate carcinogenesis after tumor-initiating events. Even treatment with low doses of testosterone alone can induce prostate cancer in rodents. Because testosterone can be converted to estradiol-17β by the enzyme aromatase, expressed in human and rodent prostate, estrogen may be involved in prostate cancer induction by testosterone. When estradiol is added to testosterone treatment of rats, prostate cancer incidence is markedly increased and even a short course of estrogen treatment results in a high incidence of prostate cancer. The active testosterone metabolite 5α-dihydrotestosterone cannot be aromatized to estrogen and hardly induces prostate cancer, supporting a critical role of estrogen in prostate carcinogenesis. Estrogen receptors are expressed in the prostate and may mediate some or all of the effects of estrogen. However, there is also evidence that in the rodent and human prostate conversion occurs of estrogens to catecholestrogens. These can be converted to reactive intermediates that can adduct to DNA and cause generation of reactive oxygen species, and thus estradiol can be a weak DNA damaging (genotoxic) carcinogen. In the rat prostate DNA damage can result from estrogen treatment; this occurs prior to cancer development and at exactly the same location. Inflammation may be associated with prostate cancer risk, but no environmental carcinogenic risk factors have been definitively identified. We postulate that endogenous factors present in every man, sex steroids, are responsible for the high prevalence of prostate cancer in aging men, androgens acting as strong tumor promoters in the presence of a weak, but continuously present genotoxic carcinogen, estradiol-17β.

Keywords: prostate; prostate cancer; estrogen, androgen; carcinogenesis; hormonal carcinogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is a very common cancer in males in most European and North American countries. In the United States it is the most frequently diagnosed nonskin malignancy in men and it is the most common cause of death from cancer. Small, microscopic-size (histologic) carcinomas in the prostate are exceedingly common in men over the age of 30 years and may occur in as many as 50% of men over 50 years of age and in 80% of men over 80 years; lifetime risk of such prostate cancer is on the order of 85%. However, clinically apparent cancer of the prostate is far less common, lifetime risk being in the range of 15–20% in most European and North American countries, and this malignancy is only clinically important in men over the age of 50 years. Why this cancer is so common and why the majority of histologic carcinomas do not progress to a clinically relevant stage within the lifetime of most men is not clear. In fact, the causes of prostate cancer are not understood even though the disease is highly prevalent (see Refs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 for reviews). Besides age, which is a strong risk factor, there are few other established risk factors, including a family history of prostate cancer, a Western lifestyle, and an African American heritage—worldwide, the incidence of clinically significant prostate cancer is highest among black Americans and is far more common in Western countries than in most Asian countries and most less-affluent societies. However, for neither risk factor are the underlying mechanisms known. Prostatitis (prostatic inflammation), which a very frequent condition as well, is suspected to be a risk factor.5 Although hard evidence for an inflammatory hypothesis remains elusive, the oxidative stress associated with inflammation offers an attractive mechanism whereby prostatitis may contribute to cancer formation.5 Another highly prevalent prostatic disease, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), is not associated with prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer is a hormone-dependent malignancy that develops from an androgen-dependent tissue that contains androgen receptors. The vast majority of prostate carcinomas initially respond to androgen ablation therapy, but later relapse to an androgen-independent (hormone-refractory) state. Because of these features, androgens are thought to be involved in the causation of prostate cancer. However, there is very little support for this notion from a variety of epidemiological studies or tissue-based investigations.6 For example, in a meta-analysis by Eaton et al.,7 there was a total absence of a relation between prediagnostic androgen levels in serum or plasma. However, there are also data in support of such a relationship8 and recent reports of an inverse relationship between risk and androgen levels.9 Another example is that even hormone-refractory prostate cancers express androgen receptors that are activated.10 While a ligand-independent mechanism is thought to be responsible for this phenomenon, it does not provide support for the hypothesis of androgens as a cause of prostate cancer in humans. The only support for a hormonal-causation hypothesis comes from the recently completed prevention study with the drug finasteride, which inhibits 5α-reductase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to the active androgen 5α-dehydrotestosterone.11 A 7-year intervention with this drug reduced prostate cancer risk in healthy men by about 25%. However, more high-grade cancers were found in those men who did develop prostate cancer while on the drug than in men who received a placebo, undercutting the notion that androgens cause possible aggressive prostate carcinomas that are likely to become clinically evident. Two interpretations of the outcome of the finasteride study might be (1) that androgens cause clinically insignificant cancers, but not prostate carcinomas that progress to become aggressive, or (2) that androgen is necessary for prostate cancer causation, but not sufficient and that other factors are major determinants of progression to the aggressive stage.

Animal studies, on the other hand, clearly demonstrate that androgens are very strong tumor promotors for prostate carcinogenesis at very low, near physiological, concentrations. This may explain why it has been difficult to find significant associations between elevated levels of circulating androgens and risk of prostate cancer. Even treatment with low doses of testosterone alone can induce prostate cancer in rats, albeit at low incidence in most strains. A single prostate-targeted tumor-initiating dose of one of several chemical carcinogens causes a low incidence of prostate carcinomas in rats. Subsequent long-term, low-dose testosterone treatment markedly increases prostate cancer yields, demonstrating the strong tumor-promoting activity of androgens.12

Testosterone can be converted to estradiol-17β by the enzyme aromatase, which is expressed in the human prostate,13 and there is indirect evidence for aromatase expression in rodent prostate (Vega and Bosland, unpublished data).14–16 Therefore, estrogen may be involved in the induction of prostate cancer by this androgen. The Noble (NBL) rat strain is very sensitive to testosterone treatment. When estradiol is added to testosterone treatment of these NBL rats, prostate cancer incidence is increased from 35–40% with androgen alone to 90–100% within approximately 1 year.17 Unpublished reports from our laboratory indicate that even a short course of estrogen treatment (for 2–4 months) is sufficient to result in a high incidence (approximately 70%) of prostate cancer in rats in the presence of chronic low-dose androgen treatment. The active testosterone metabolite 5α-dihydrotestosterone cannot be aromatized to estrogen and does not induce prostate cancer in more than 5% of treated rats, supporting the notion that estrogen plays a critical role in prostate carcinogenesis.18 However, when estradiol is added to the androgen treatment, cancer formation does not nearly increase as much as when estradiol is given with testosterone. Unfortunately, experiments with just estrogen treatment result in the shutdown of endogenous androgen production due to reduction of LH production via the pituitary feedback, and this leads to prostate atrophy, which renders prostate carcinogenesis studies impossible. Studies with aromatase knockout mice16 and aromatase-overexpressing mice14,15 are potentially interesting, but these mice suffer from androgen abnormalities that make their interpretation limited. Aromatase knockout mice lack estrogen production, but have elevated testosterone levels and prostate enlargement but no cancer.16 Aromatase-overexpressing mice have elevated estrogen production, but markedly reduced testosterone levels, and develop no prostate lesions related to cancer. 14,15 Both observations are consistent with the notion that both hormones are necessary for prostate cancer development.

The estrogen receptors-α and -β are expressed in the prostate and may mediate some or all of the effects of estrogen.19–21 Indeed, simultaneous treatment of NBL rats with estradiol plus testosterone and an antiestrogen (ICI 182,780) inhibits the development of dysplasia in the prostate (or murine prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia), a putative preneoplastic lesion.22 On the other hand, there is no effect of administration of another antiestrogen, tamoxifen, to rats treated with low-dose testosterone after exposure to a prostate-directed carcinogen; prostate cancer yield remained high in these rats.23 One effect of estradiol treatment of rats is the estrogen receptor–mediated induction of enlargement and tumors of the pituitary gland, which leads to marked elevation of circulating prolactin. These effects are counteracted by treatment with antiestrogens. High circulating levels of prolactin are known to produce prostatic inflammation in rats,24 and treatment with antiestrogens lowers prolactin in estrogen-treated rats and reduces inflammation.22 Because inflammation may be associated with reactive hyperplasia similar to the aforementioned dysplasia, the inhibition of dysplasia development by antiestrogens in rats treated with estradiol plus testosterone may simply be due to the lowering of prolactin in these animals. Indeed, treatment of these steroid hormone–exposed rats with an antiprolactin drug, bromocryptin, not only lowers prolactin levels, but also inhibits the development of dysplasia and inflammation in the prostate.25 Of note, the dysplasia and inflammation in NBL rats treated with estradiol plus estosterone occur in the same region of the prostate (dorsolateral prostate), whereas carcinomas in these animals originate in another region (the periurethral area); 17 the dysplasia in the dorsolateral prostate only rarely progresses to cancer (Bosland, unpublished results). The studies with the ICI antiestrogen and bromocryptin did not last sufficiently long to determine their effects on the induction of periurethral prostate carcinomas. Taken together, these data (1) do not support a major role of estrogen receptors in the induction of prostate cancer or dysplasia, but conclusive studies are lacking at present, and (2) indicate that prolactin appears to play a role in the generation of dorso-lateral prostate dysplasia in NBL rats treated with estradiol plus testosterone, but it is not clear whether this hormone is involved in cancer formation. There is a notion that the estrogen receptor-β may mediate inhibition of the progression of prostate cancer,21 but this is not a generally accepted and validated concept at present.

There is also evidence from partially published results of the author in collaboration with E. Cavalieri and E. Rogan (unpublished results)26 that, in the rodent and human prostate, conversion occurs of estradiol and estrone to catecholestrogen, 2- and 4-hydroxyestrogens. These catecholestrogens can be converted to estrogen semiquinones and estrogen quinones by the process of redox cycling; these are reactive intermediates that can adduct to DNA and cause generation of reactive oxygen species.27,28 The DNA adducts formed by the 4-hydroxyestrogen quinones depurinate, leading to apurinic sites in the DNA, which can lead to the generation of mutations by error-prone DNA repair processes.29 Indeed, there is evidence from experiments in other tissues indicating that estradiol can be a weak DNA damaging (genotoxic) carcinogen.30 Partially published results from studies by the author in collaboration with E. Cavalieri and E. Rogan indicate that these reactions can take place in the rat prostate26 and possibly the human prostate. In addition, there is some evidence that in the NBL rat prostate DNA damage results from estrogen treatment and that this occurs prior to cancer development and at the exact same location within the rat prostate where carcinomas develop after treatment with estradiol plus testosterone.31,27,26 There are enzymes, such as catechol-O-methyltransferase and glutathione reductase, that protect against these reactive estrogen metabolites. These protective enzymes appear to be more active in the dorsolateral prostate region, which does not develop cancer in NBL rats treated with estradiol plus testosterone, and less active in the periurethral prostate area, where carcinomas do develop.26

As indicated above, no environmental carcinogenic factors associated with prostate cancer risk have been definitively identified and the causes of this very prevalent malignancy remain elusive. Therefore, it is attractive to postulate that endogenous factors present in every man, namely sex steroids, are responsible for the high frequency of prostate cancer in aging men. If one hypothesizes that androgens act as strong tumor promotors, the presence within the prostate of a weak, but ubiquitously and continuously present genotoxic carcinogen, estradiol-17β, may be sufficient to cause prostate cancer at high prevalence in humans just as it appears to do in the NBL rat model. The increase in estrogen-to-androgen ratio that occurs in aging men 32 can be viewed as support for the notion that estrogens, in addition to androgens, are critical factors in prostate carcinogenesis. This hypothesis may explain why prostate cancer is so common. However, it does not explain why some tumors progress to be clinically evident and aggressive, while others remain apparently indolent. It also does not explain why this process of progression is far more common in Western countries, particularly among African American men, than in most Asian countries, while migrants from low-risk to high-risk countries acquire the risk of their new environment.1–3 Clearly, there are other factors than hormones per se that play a decisive role. There may be genetic, hereditary factors as well as environmental factors determining (1) the sensitivity of the androgen receptor for 5α-dehydrotestosterone and (2) critical steps in the metabolism of androgens (5α-reductase) and estrogens (aromatase and the enzymes involved in generation of and protection against reactive estrogen metabolites). Indeed, prostate cancer risk appears associated with the length of a CAG repeat sequence in the coding region of the androgen receptor, which is known to affect androgen receptor activity. Short CAG repeat lengths in this region are associated with higher androgen receptor activity and higher prostate cancer risk, and they are more common in African Americans than in other racial groups.1,4 There is also some evidence to suggest that 5α-reductase activity is lower in Asian men than in other ethnic groups.33 However, both associations are not consistently found and there are contradictory reports and there are no consistent relationships between genetic polymorphisms in the 5α-reductase gene and prostate cancer risk.1,4 There is no doubt that there are environmental factors, which are critical determinants of risk of clinically evident prostate cancer, explaining the changes in prostate cancer risk in migrants from low- to high-risk countries, but these factors have not been identified.

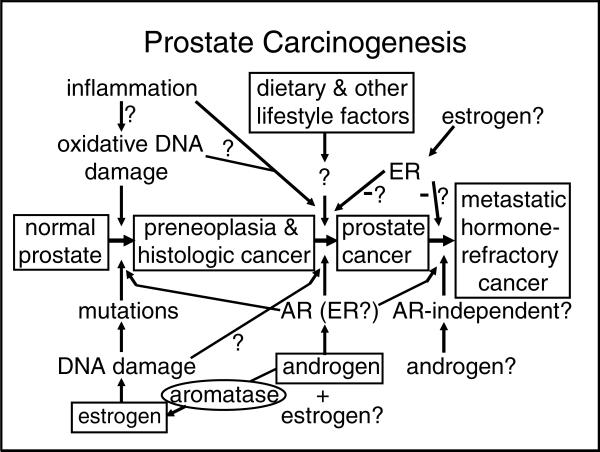

In conclusion, prostate carcinogenesis appears to be a highly multifactorial process in which hormones, both androgens and estrogen, play a central role. A causative role of inflammation has been proposed, but evidence for this notion is not very strong at present. Environmental and genetic factors may determine in large part the risk of clinically significant prostate cancer by affecting the rate of progression of early-stage carcinomas; steroid hormone effects may be responsible for the very high prevalence of prostate cancer. If one hypothesizes that androgens act as strong tumor promotors, the presence of a weak, but ubiquitously and continuously present genotoxic carcinogen, estradiol-17β, may be sufficient to cause prostate cancer at high prevalence. Although this hypothesis (FIG. 1) does not take into account some of the important intricacies of prostate biology such as stromal–epithelial interrelationships and factors such as the IGF axis, it provides a new framework on which to base novel approaches to understanding prostate carcinogenesis. Moreover, this proposed mechanism may offer opportunities for preventive interventions by agents that inhibit formation of reactive estrogen metabolites that damage DNA or enhance enzymatic factors that provide protection against these metabolites.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the proposed hypothesis of prostate carcinogenesis involving three steps: (1) the formation of preneoplasia (high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia) and histologic carcinoma; (2) progression to clinically significant (aggressive) carcinoma; and (3) further progression to metastatic and hormone-refractory carcinoma. Four proposed major determinants of these steps—estrogen, androgen, aromatase, and dietary and lifestyle factors—are indicated within text boxes. Less certain factors and mechanisms involved in prostate carcinogenesis, such as inflammation, androgen receptor (AR), and estrogen receptors (ER), are not placed within a text box and are identified with question marks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results from our laboratory have been supported in part by NIH Grants No. CA104334 and CA75293, and the collaborations between the author and E. Cavalieri and E. Rogan have been supported in part by NIH Grant No. CA49210 and DOD Grant No. DAMD 17-02-1-0660.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bosland MC. The role of steroid hormones in prostate carcinogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2000;27:39–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JM, Gann PH, Giovannucci EL. Role of diet in prostate cancer development and progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:8152–8160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gann PH. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Rev. Urol. 2002;4(Suppl 5):S3–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platz EA, Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of sex steroid hormones and their signaling and metabolic pathways in the etiology of prostate cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;92:237–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palapattu GS, Sutcliffe S, Bastian PJ, et al. Prostate carcinogenesis and inflammation: emerging insights. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1170–1181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgentaler A. Testosterone and prostate cancer: an historical perspective on a modern myth. Eur. Urol. 2006 Jul 27;50:935–939. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.034. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton NE, Reeves GK, Appleby PN, Key TJ. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a quantitative review of prospective studies. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;80:930–934. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, et al. Prospective study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1118–1126. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.16.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severi G, Morris HA, MacInnis RJ, et al. Circulating steroid hormones and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:86–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taplin ME, Balk SP. Androgen receptor: a key molecule in the progression of prostate cancer to hormone independence. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;91:483–490. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosland MC, Dreef-van der Meulen HC, Sukumar S, et al. Multistage prostate carcinogenesis: the role of hormones.. In: Harris CC, Hirohashi S, Ito N, Pitot HC, Sugimura T, Terada M, Yokota J, editors. Multistage Carcinogenesis; Proceedings of the 22nd International symposium of the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund.; Boca Raton, FL.: Tokyo, Japan: Japan Sci. Soc. Press; CRC Press; 1992. pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellem SJ, Schmitt JF, Pedersen JS, et al. Local aromatase expression in human prostate is altered in malignancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:2434–2441. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler KA, Gill K, Kirma N, et al. Overexpression of aromatase leads to development of testicular leydig cell tumors: an in vivo model for hormone-mediated testicular cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:347–353. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64736-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Nokkala E, Yan W, et al. Altered structure and function of reproductive organs in transgenic male mice overexpressing human aromatase. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2435–2442. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson SJ, Wang H, Jones ME, et al. Elevated androgens and prolactin in aromatase-deficient mice cause enlargement, but not malignancy, of the prostate gland. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2458–2467. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosland MC, Ford H, Horton L. Induction of a high incidence of ductal prostate adenocarcinomas in NBL and Sprague Dawley rats treated with estradiol-17β or diethylstilbestrol in combination with testosterone. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1311–1317. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.6.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosland MC, Ford H, Horton L, et al. Progression of putative precursor lesions of rat prostatic adenocarcinomas induced by estradiol-17β and androgens. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1995;36:271. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latil A, Bieche I, Vidaud D, et al. Evaluation of androgen, estrogen (ER alpha and ER beta), and progesterone receptor expression in human prostate cancer by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1919–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau KM, Leav I, Ho SM. Rat estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, and progesterone receptor mRNA expression in various prostatic lobes and microdissected normal and dysplastic epithelial tissues of the Noble rat. Endocrinology. 1998;139:424–427. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leav I, Lau KM, Adams JY, et al. Comparative studies of the estrogen receptors beta and alpha and the androgen receptor in normal human prostate glands, dysplasia, and in primary and metastatic carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;59:79–92. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61676-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson CJ, Tam NN, Joyce JM, et al. Gene expression profiling of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta-induced prostatic dysplasia in Noble rats and response to the antiestrogen ICI 182,780. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2093–2105. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick DL, Johnson WD, Lubet RA, et al. Differential chemopreventive activity of the antiandrogen, flutamide, and the antiestrogen, tamoxifen, in the rat prostate. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2002 [abstract 3178] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tangbanluekal L, Robinette CL. Prolactin mediates estradiol-induced inflammation in the lateral prostate of Wistar rats. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2407–2416. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lane KE, Leav I, Ziar J, et al. Suppression of testosterone and estradiol-17beta-induced dysplasia in the dorsolateral prostate of Noble rats by bromocriptine. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1505–1510. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.8.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavalieri EL, Devanesan PD, Bosland MC, et al. Catechol estrogen metabolites and conjugates in different regions of the prostate of Noble rats treated with 4-hydroxyestradiol: implications for estrogen-induced initiation of prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:329–333. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavalieri E, Frenkel K, Liehr JG, et al. Estrogens as endogenous genotoxic agents–DNA adducts and mutations. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2000;27:75–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalieri E, Chakravarti D, Guttenplan J, et al. Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers: implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1766:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mailander PC, Meza JL, Higginbotham S, Chakravarti D. Induction of A.T to G.C mutations by erroneous repair of depurinated DNA following estrogen treatment of the mammary gland of ACI rats. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006 Sep 16;101:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liehr JG. Role of DNA adducts in hormonal carcinogenesis. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2000;32:276–282. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han X, Liehr JG, Bosland MC. Induction of a DNA adduct detectable by 32P-postlabeling in the dorsolateral prostate of NBL/Cr rats treated with estradiol-17β and testosterone. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:951–954. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Goemaere S, van Pottelberg I. Estradiol in elderly men. Aging Male. 2002;5:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross RK, Bernstein L, Lobo RA, et al. 5-alpha-reductase activity and risk of prostate cancer among Japanese and US white and black males. Lancet. 1992;339:887–889. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90927-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]