SYNOPSIS

Most California prisoners experience discontinuity of health care upon return to the community. In January 2006, physicians working with community organizations and representatives of the San Francisco Department of Public Health's safety-net health system opened the Transitions Clinic (TC) to provide transitional and primary care as well as case management for prisoners returning to San Francisco. This article provides a complete description of TC, including an illustrative case, and reports information about the recently released individuals who participated in the program.

From January 2006 to October 2007, TC saw 185 patients with chronic medical conditions. TC patients are socially and economically disenfranchised; 86% belong to ethnic minority groups and 38% are homeless. Eighty-nine percent of patients did not have a primary care provider prior to their incarceration. Preliminary findings demonstrate that a community-based model of care tailored to this disenfranchised population successfully engages them in seeking health care.

Approximately 700,000 people are released from U.S. federal and state prisons each year.1 They are disproportionately poor members of minority groups with a high prevalence of low educational attainment, prior homelessness, and unemployment.2 Upon release, they must obtain housing, find employment, and reunite with family. The more than 70% of prisoners with chronic medical, substance abuse, and other mental health problems1,3,4 face the additional challenge of addressing their health needs. Few prison systems release individuals with medications, health insurance, or primary care referrals.5,6 Recently released individuals have poor access to primary care and high rates of emergency department use and death compared with the general population.7,8

The best known models for bridging health care from correctional facilities to the community involve health-care providers and case managers who work both in the correctional facilities and in the community to ensure continuity of care. These programs are effective in smaller geographic settings5,9,10 or in jails, which are typically short-term confinement facilities located in the community. However, they are difficult to replicate in state and federal prison systems that release prisoners to distant communities.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, one of the nation's largest state prison systems, releases more than 130,000 individuals annually from 33 prisons. Approximately 2,000 individuals are released annually to San Francisco County under parole supervision.11 Only prisoners with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or severe psychiatric disorders receive prerelease health-care planning, leaving other chronically ill individuals with limited medications and no plans for primary care upon release.12,13

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

In 2005, two physicians convened a meeting of formerly incarcerated individuals and community organizations to discuss starting a program to address the transitional and primary health-care needs of recently released individuals returning to San Francisco from California state prisons. Although there was also a perceived need for transitional health-care services for individuals released from the San Francisco County Jail, the physicians' efforts focused on individuals being released from prison who served longer sentences and traditionally had fewer services upon release. With community input and support, the founding physicians established the Transitions Clinic (TC) in January 2006 in collaboration with leaders at Southeast Health Center, a San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) community health center.

TC provides chronically ill individuals recently released from prison with medical care and coordinated social services. TC aims to promote healthy reintegration, improve health-care utilization, and decrease prison recidivism. The clinic is based at Southeast Health Center, which is located in the neighborhood with the largest population of formerly incarcerated individuals in San Francisco.

At TC, patients receive (1) care from a physician with experience working with formerly incarcerated individuals, (2) referrals to community organizations that serve these individuals, and (3) case management from a community health worker (CHW) with a history of previous incarceration (the latter was added in April 2007). The two founding physicians volunteer to see patients one afternoon per week and coordinate health-care and social services with help from a full-time CHW. Each physician sees about one to two new and four to five returning patients per afternoon.

Hired in April 2007 with funding from private foundation grants, the clinic's CHW attends mandatory weekly parole meetings with 20–30 recently released individuals. He schedules appointments at TC within two weeks for anyone with a chronic illness (including substance abuse) and all individuals older than age 50 on a voluntary basis. Typically, six to eight parolees choose to schedule an appointment each week. Additional referrals also come from community organizations serving formerly incarcerated individuals and from urgent care clinics and the San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (SFGH) emergency department. At the initial visit, a physician addresses urgent medical issues, screens for infectious diseases, refills medications, and refers patients to specialty care as necessary. If the patient has an existing relationship with a primary care provider, the CHW helps to reestablish care with that provider for all future follow-up visits and continuity of care. If they do not have a primary care provider, the CHW helps establish ongoing care at TC or with another provider at a SFDPH community clinic.

The CHW provides case management services for a caseload of 30–40 patients. Services include assistance with housing, employment, legal aid, substance abuse counseling, health-care system navigation, and chronic disease self-management support. The CHW applies skills learned both through formal training in the City College of San Francisco CHW certificate program (http://www.ccsf.edu/Departments/Health_Education_and_Community_Health_Studies/chw/chw.html) and through his own experience as someone with a previous history of incarceration, homelessness, and addiction.

TC patients have access to existing onsite Southeast Health Center services, including urgent care, social work, substance abuse counseling, psychiatry, and laboratory services, as well as imaging services and specialty care at SFGH, a publicly funded hospital affiliated with the SFDPH community-based clinics. Community partners provide additional drug treatment, employment, and educational services; housing; and other services for recently released individuals upon referral.

Per SFDPH protocol, patients pay for services and medications based on income. Uninsured patients with incomes <300% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are charged based on a sliding-scale program. SFDPH provides care without copayments for the homeless and those earning <100% FPL. In April 2007, the SFDPH rolled out Healthy San Francisco, a program that provided a primary medical home to participants, allowing a greater focus on preventive care, as well as specialty care, urgent and emergency care, mental health care, substance abuse services, laboratory, radiology, and pharmaceutical services. Patients who earned <300% FPL qualified for participation in the program.

This model of transitional and primary health care was designed with input from individuals with a history of incarceration and continues to be informed by a community advisory board with 50% representation of formerly incarcerated individuals. Meeting quarterly, the advisory board looks at issues of outreach, program retention, advocacy for changes in public policy, and dissemination of project outcomes. Prior to TC, there was no established program of targeted, transitional, or primary medical care services in place to specifically address the health-care needs of individuals being released from prison to San Francisco.

CASE ILLUSTRATION

After nine years of incarceration, a 49-year-old man with diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was recently released from a California state prison without medication or a follow-up appointment with a primary care physician. He has a long-standing history of heroin and cocaine use that was not treated while behind bars, where he has spent the majority of his adult life. During this last prison sentence, he was diagnosed with diabetes; prison nurses managed his medication regimen, and prison policy dictated his diet and physical activity. Upon release, he did not know how to manage his own chronic illnesses, he was unfamiliar with the community health-care system, and he did not know where to obtain medication or find a primary care provider. He was also unemployed and homeless, living at a local shelter.

At a mandatory parole meeting a few days after his release, he met the TC CHW, who scheduled an appointment for him two days later. The day prior to his appointment, the CHW gave him a reminder call and offered to help him find the clinic. The patient arrived at Southeast Health Center and was seen by a TC physician, who refilled his medications, screened him for infectious diseases, and discussed health risks specific to his recent incarceration. The patient's Medicaid expired while in prison, and the patient did not have insurance or the financial resources to pay for his medication. The physician referred the patient to the social worker to reapply for health insurance. In the interim, he received coverage for his health care and prescription medications through the SFDPH protocol, which covers services and medication for individuals who are indigent or homeless.

During this visit, the patient tested positive for hepatitis C and was found to have post-traumatic stress disorder from a violent encounter in prison. He was referred to a hepatologist and psychiatrist. The clinic's CHW found temporary shelter for the patient and referred him to community substance abuse treatment. As he did not have a primary care provider prior to incarceration, he was followed longitudinally in TC. During the next few weeks, the CHW visited him in the shelter, accompanied him to his first appointments with the psychiatrist, and provided diabetes self-management support. During the next few months, the patient began taking methadone and was referred to various employment agencies. He is currently working full-time in Goodwill Industries and has not been re-arrested.

RESULTS

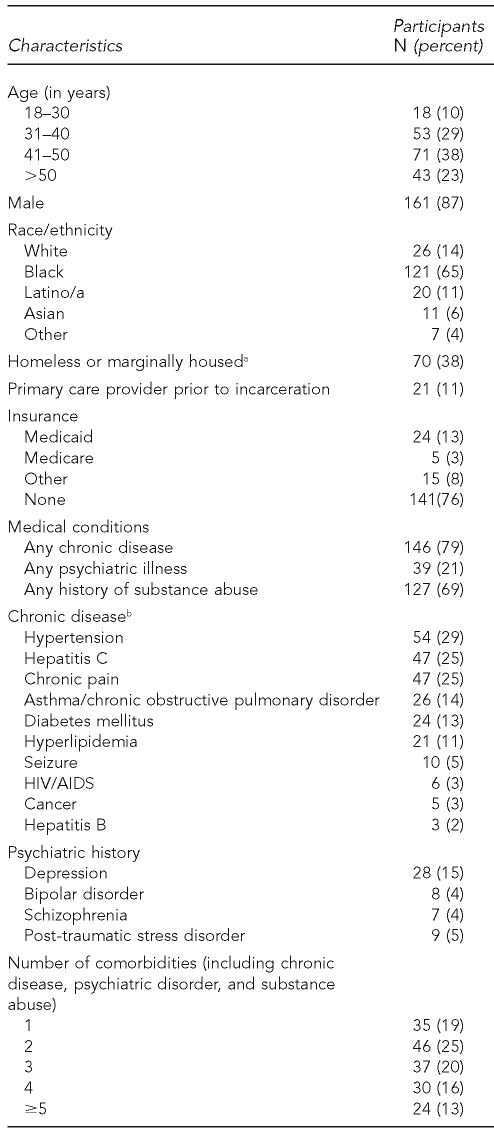

We abstracted information from computerized medical records on 185 unduplicated patients seen at TC from January 2006 to October 2007. This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco's Committee on Human Research. We found that patients had a high burden of chronic diseases and comorbidities (Table). While all these individuals had a chronic medical condition requiring continued primary care, only 11% had a primary care physician in San Francisco prior to incarceration. Thirty-eight percent were homeless or housed in a transitional drug treatment program, 75% were unemployed, and half reported no income.

Table.

Characteristics of Transitions Clinic patients, San Francisco, January 2006 to October 2007 (n=185)

aIndividuals reported either being homeless (living on the streets or in the shelter system) or staying in temporary drug treatment programs for recently released inmates.

bThese are the top 10 chronic diagnoses seen in Transitions Clinic patients at presentation.

HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

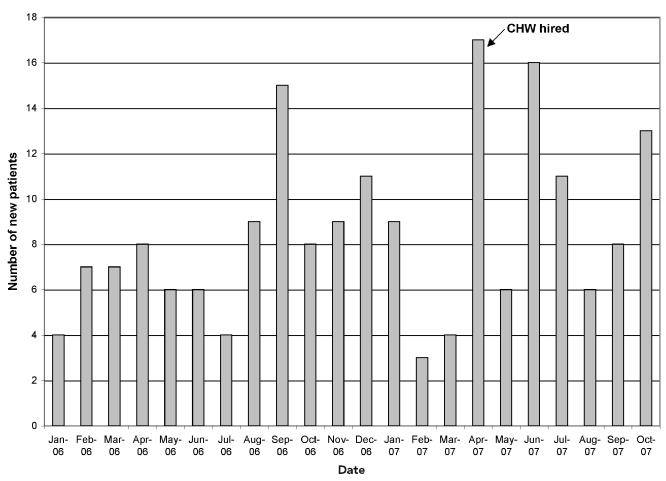

Nonetheless, the clinic's show rates were 55% for initial appointments, with a six-month follow-up rate of 77%, compared with 40% and 46%, respectively, for non-TC patients seen at Southeast Health Center, as reported by the clinic director (Personal communication, Mark Ghaly, MD, Director of Southeast Health Center, SFDPH, September 2008). In addition, after hiring the CHW, the mean number of new patients increased from seven per month to 11 per month (Figure) without an increase in initial appointment show rate. The CHW worked with patients in a broad catchment area; only 25% of the patients he followed live in the area surrounding the Southeast Health Center.

Figure.

Number of new patients per month at Transitions Clinic in San Francisco, January 2006 to October 2007

CHW = community health worker

DISCUSSION

We launched this clinic amid strong interest in improving health care in California prisons and reentry services in the community. In 2006, U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson found that substandard medical care in the California prison system had violated prisoners' rights under the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. He appointed a federal receiver to oversee the improvement of medical care in the California prison health-care system to constitutional standards. Simultaneously, a group of city leaders, community agencies, and formerly incarcerated individuals began working together to improve coordination of housing, employment, and legal services for individuals returning to San Francisco from jail or prison through a citywide reentry initiative. However, with the exception of programs for HIV-positive individuals and patients with severe mental illness, statewide reentry efforts overlooked the health needs of chronically ill individuals returning to San Francisco. TC filled this gap in San Francisco by providing targeted transitional and primary medical care services for individuals being released from California state prison.

This provided an initial impetus for funding. However, despite filling a need for health-care services, the clinic still faces the challenge of long-term sustainability. To provide evidence of the clinic's effectiveness, we are currently employing a randomized controlled trial to examine patterns of health-care utilization and recidivism of patients receiving longitudinal care at TC compared with those who receive only transitional care and expedited referral to primary care in the community. This evaluation will inform program expansion and replication decisions, as the number of individuals returning from prison continues to rise and local health departments look for effective ways to care for chronically ill individuals released from prison.

As we await the results of the randomized controlled trial, our experience creating and developing the TC and the results presented in this article provide lessons that can inform the establishment of other health-care interventions for this vulnerable population. First, as communities throughout the country create programs targeting chronically ill individuals released from prison, it is important to incorporate both the input of formerly incarcerated individuals and the existing evidence base in the development of these programs. Community members advised us from the onset, guiding decisions as we conceived and developed our clinic. For instance, a focus group with our patients helped to create a clinic policy for a challenging but common clinical scenario: the performance of urine toxicology screening for patients on parole with a history of substance abuse that were being treated for chronic pain with opiates.

Additionally, the successes and limitations of prior reentry interventions with incarcerated chronically ill adults should inform future efforts. Successful reentry programs designed for HIV-positive individuals14 or those with severe mental illness focus on reducing HIV risk and coordinating ongoing treatment between the correctional setting and the community. Many of these interventions involve a transitional care team that connects with individuals while incarcerated and follows them upon release. 10,15 While this model is successful in smaller correctional systems such as local jails, it is not a feasible design for many larger state prison systems. Other models offered important lessons for TC. For instance, an evaluation of Health Link, a reentry case management program targeting adolescent men and women in Riker's Island Jail in New York City, demonstrates that health-care interventions need to be accessible immediately upon release for optimal utilization and impact.16 Prior research also demonstrates that the first two weeks after release are a high-risk period for poor health outcomes, including death.8 As a result, we designed TC to be available to all individuals within two weeks of release from prison.

Our experience shows that it is possible to engage recently released individuals with chronic medical conditions in a voluntary program to address their physical health concerns. Previous research indicates that health issues are among the lowest priorities for individuals returning from prison.17 Nonetheless, our experience suggests that many formerly incarcerated adults will engage in health care within two weeks of their release. Further, the participation of a CHW, who is well versed in the cultural, social, and environmental forces that shape our patients' lives, extended the reach of our intervention. The CHW mitigates the mistrust that prevails in this population, increases the number of individuals reached by our intervention, and enhances their engagement with other social services. In this context, the demand for health-care services has exceeded our capacity in a half-day clinic, and we are moving toward adding another half-day to the clinic operations and an additional CHW to our clinic staff.

Further support for the expansion of our clinic comes from the fact that we were able to engage a population with a disproportionately high number of minority individuals into seeking health care.18,19 Reentry health-care programs may offer a novel way to reduce persistent socioeconomic and racial disparities in chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. Eighty-six percent of the patients seen at TC are members of racial/ethnic minority groups (i.e., 65% black, 11% Latino, 6% Asian, and 4% other), a proportion higher than the overall racial makeup of the California Department of Corrections (i.e., 29% black, 38% Latino, and 6% other). Because there are a disproportionate number of people from racial/ethnic minority groups incarcerated, reentry health-care programs can be a vehicle for addressing entrenched racial/ethnic disparities in health and health-care access using culturally appropriate methods for delivering care.

Finally, this program was established in a preexisting community health center in the San Francisco neighborhood to which the largest proportion of individuals returning from state prison will live. As such, this intervention required little in terms of start-up funding and can be replicated in other safety-net health-care systems with basic training for primary care providers who are unfamiliar with the unique issues of caring for previously incarcerated populations; the addition of a CHW; and partnerships with community organizations already providing social services to this population. Although the Southeast Health Center is a county-funded community health center, it is not unlike many Health Resources and Services Administration-funded federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in the populations it serves. As these FQHCs are often already located in communities with a high prevalence of formerly incarcerated individuals and are already engaged in the provision of care to these patients and their families, these health centers may be an ideal place for targeted health interventions for individuals recently released from prison. Modest amounts of funding from either federal or state governments to FQHCs could extend health care to hundreds of thousands of formerly incarcerated individuals and complement government efforts to improve health care for these individuals while they are incarcerated.

CONCLUSION

TC provides the growing population of chronically ill individuals recently released from the California state prison system with medical care and coordinated social services. The clinic aims to promote healthy reintegration, improve health-care utilization, and decrease prison recidivism. It is a model of care that can be replicated in other safety-net health centers or FQHCs, with basic training for physicians in caring for patients with a history of incarceration, the hiring of a CHW, and partnerships with existing community organizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the entire staff of Southeast Health Center, particularly Doralee Chavez, Ricardo Duarte, Dr. Mark Ghaly, Lula Hobbs, and Dr. Dan Wlodarczyk; the community partners Legal Services for Prisoners with Children and City College of San Francisco for their advice and support of Transitions Clinic; and the generous funders The California Endowment, California Wellness Foundation, the San Francisco Foundation, and Catholic Healthcare West.

Footnotes

Emily Wang was supported by the National Research Service Award Research Training Grant in General Internal Medicine to the University of California, San Francisco (T32 HP 19025). Clemens Hong was supported by a grant from the Human Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services to support the Harvard Medical School Fellowship in General Medicine and Primary Care (T32 HP 12706).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2006. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Department of Justice (US); 2007. Revised 2008 Mar 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harlow CW. Education and correctional populations. Washington: Department of Justice (US); 2003. Revised 2003 Apr 15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates: a report to Congress. Chicago: NCCHC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maruschak L, Beck AJ. Medical problems of inmates. Washington: Department of Justice (US); 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lincoln T, Kennedy S, Tuthill R, Roberts C, Conklin TJ, Hammett TM. Facilitators and barriers to continuing healthcare after jail: a community-integrated program. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:2–16. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan NA. Transitional health care for offenders being released from United States prisons. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36:38–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leukefeld CG, Hiller ML, Webster JM, Tindall MS, Martin SS, Duvall J, et al. A prospective examination of high-cost health services utilization among drug using prisoners reentering the community. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11414-005-9006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vigilante KC, Flynn MM, Affleck PC, Stunkle JC, Merriman NA, Flanigan TP, et al. Reduction in recidivism of incarcerated women through primary care, peer counseling, and discharge planning. J Womens Health. 1999;8:409–15. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich JD, Holmes L, Salas C, Macalino G, Davis D, Ryczek J, et al. Successful linkage of medical care and community services for HIV-positive offenders being released from prison. J Urban Health. 2001;78:279–89. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. California prisoners and parolees 2007: summary statistics on adult felon prisoners and parolees, civil narcotic addicts, and outpatients and other populations. Sacramento (CA): California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; 2008. [cited 2009 Oct 30]. Also available from: URL: CalPris/CALPRISd2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Transitional case management project: for inmates with human immunodeficiency virus disease: evaluation number two. 1996. Report No. NCJ 180544.

- 13.California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Mental health services continuum program overview. 2004. [cited 2009 Oct 30]. Available from: URL: http://docs.google.com/gview?a=v&q=cache:g3O-WGJLonEJ:www.adp.ca.gov/SACPA/pdf/06-04_Attachment_Overview.pdf+An+evaluation+of+California%27s+Mental+Health+Services+Continuum+Program+for+parolees.&hl=en&gl=us&sig=AFQjCNFCXm55FOvBcE3G4sVe4vjOdS7piQ.

- 14.Copenhaver M, Chowdhury S, Altice FL. Adaptation of an evidence-based intervention targeting HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community: the process and outcome of formative research for the Positive Living Using Safety (PLUS) intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:277–87. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob Arriola KR, Braithwaite RL, Holmes E, Fortenberry RM. Post-release case management services and health-seeking behavior among HIV-infected ex-offenders. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:665–74. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunch W. Helping former prisoners reenter society: the Health Link Project. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallik-Kane Kamala, Visher C. Health and prisoner reentry: how physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Washington: Urban Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB, Bray SJ, Mattocks K. Black-white disparities in HIV/AIDS: the role of drug policy and the corrections system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl B):140–56. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziedenberg J, Shiraldi V. Race and imprisonment in Texas: the disparate incarceration of Latinos and African Americans in the Lone Star State. Washington: Justice Policy Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]