SYNOPSIS

Since the early years of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, stigma has been understood to be a major barrier to successful HIV prevention, care, and treatment. This article highlights findings from more than 10 studies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America—conducted from 1997 through 2007 as part of the Horizons program—that have contributed to clarifying the relationship between stigma and HIV, determining how best to measure stigma among varied populations, and designing and evaluating the impact of stigma reduction-focused program strategies. Studies showed significant associations between HIV-related stigma and less use of voluntary counseling and testing, less willingness to disclose test results, and incorrect knowledge about transmission. Programmatic lessons learned included how to assist institutions with recognizing stigma, the importance of confronting both fears of contagion and negative social judgments, and how best to engage people living with HIV in programs. The portfolio of work reveals the potential and importance of directly addressing stigma reduction in HIV programs.

Early in the history of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, the late Jonathan Mann, former head of the World Health Organization's (WHO's) Global Program on Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), identified stigma as the “third epidemic,” following the accelerating spread of HIV infection and the visible rise in AIDS cases. He recognized that stigma, discrimination, blame, and denial are potentially the most difficult aspects of HIV/AIDS to address, yet addressing them is key to preventing HIV transmission and mitigating the impacts of the disease on individuals, families, and communities.1

When the Horizons program began in 1997, stigma's insidious role in the spread of HIV was widely recognized, and a few programs attempted to address its impact. Yet despite this increased awareness, there was limited understanding of the underlying drivers of stigma or the specific ways in which stigma affects HIV outcomes, a lack of tools to reliably and effectively measure stigma and discrimination, and a dearth of information about which types of intervention strategies most successfully reduce stigma in different settings.

In response to this need, Horizons developed and implemented a wide range of activities in collaboration with numerous local and international partners in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This article summarizes the key contributions of the Horizons stigma portfolio to describing the drivers of stigma, identifying effective interventions and approaches for reducing stigma in different settings, and improving methods for measuring stigma.

ARTICULATING THE ISSUES

To guide its operations research agenda, Horizons initially carried out three key activities to take stock of what was known about HIV-related stigma and ways to reduce it. In 1999, Horizons co-hosted a technical workshop with San Francisco State University that brought together stigma and HIV/AIDS experts. Horizons then published a literature review of stigma intervention strategies to date.2 The third activity was an examination of existing conceptual frameworks and the development of new approaches for intervening on stigma and discrimination.3 Findings from these activities showed the following:

Stigma occurs at multiple levels, including the interpersonal, institutional (e.g., health facilities, schools, and workplaces), community, and legislative levels.

Manifestations of stigma take many forms, including isolation, ridicule, physical and verbal abuse, and denial of services and employment.

Experiences of stigma can differ by sex, reflecting broader gender inequalities. For example, women may be more likely to be blamed for bringing HIV into the household than men.

HIV-related stigma reinforces existing stigmas against marginalized groups (e.g., men who have sex with men [MSM], sex workers, and injection drug users)—often called “compounded” stigma.

Common stigma-reduction interventions have focused mainly on creating changes in individual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors rather than broader social and environmental change.

There have been very few rigorous evaluations of stigma-reduction interventions in the developing world.

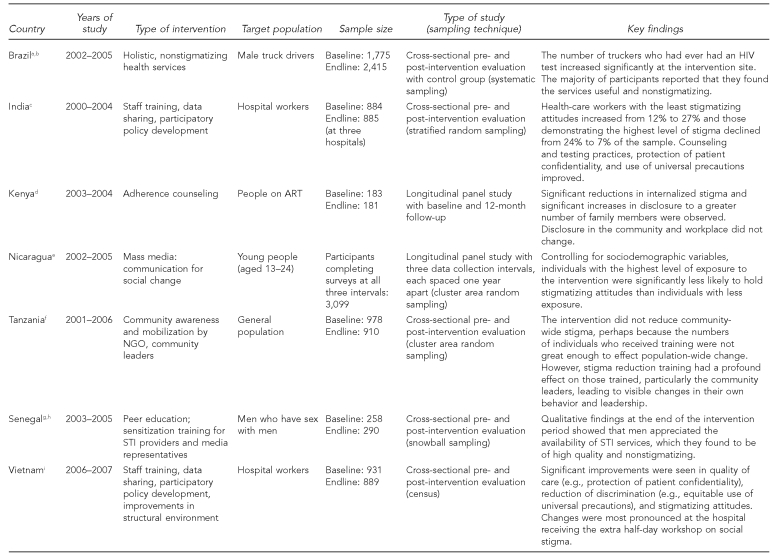

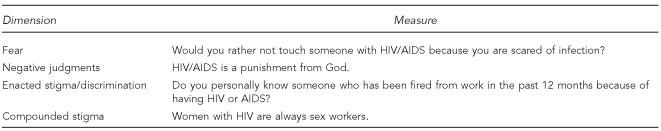

The conceptualization of stigma as a deeply rooted social process with different manifestations at various levels of society had important implications for the development of the Horizons program's global operations research agenda. This article highlights findings from Horizons intervention studies that tested a range of innovative stigma-reduction strategies at the institutional and community levels to achieve individual, social, and environmental change (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of Horizons' intervention studies on stigma and discrimination, 1997–2007

aChinaglia M, Lippman SA, Pulerwitz J, de Mello M, Homan R, Díaz J. Reaching truckers in Brazil with non-stigmatizing and effective HIV/STI services. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

bPulerwitz J, Michaelis AP, Lippman SA, Chinaglia M, Diaz J. HIV-related stigma, service utilization, and status disclosure among truck drivers crossing the Southern borders in Brazil. AIDS Care 2008;20:764-70.

cMahendra VS, Gilborn L, George B, Samson L, Mudoi R, Jadav S, et al. Reducing AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Indian hospitals. Horizons Final Report. New Delhi: Population Council; 2006.

dKaai S, Sarna A, Luchters S, Geibel S, Munyao P, Mandaliya K, et al. Changes in stigma among a cohort of people on antiretroviral therapy: findings from Mombasa, Kenya. Horizons Research Summary. Nairobi: Population Council; 2007.

eSolórzano I, Bank A, Peña R, Espinoza H, Ellsberg M, Pulerwitz J. Catalyzing personal and social change around gender, sexuality, and HIV: impact evaluation of Puntos de Encuentro's communication strategy in Nicaragua. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

fNyblade L, MacQuarrie K, Kwesigabo G, Jain A, Kajula L, Philip F, et al. Moving forward: tackling stigma in a Tanzanian community. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

gNiang CI, Tapsoba P, Weiss E, Diagne M, Niang Y, Moreau A, et al. “It's raining stones”: stigma, violence, and HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men in Dakar, Senegal. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2003;5:499-512.

hMoreau A, Tapsoba P, Ly A, Niang CI, Diop AK. Implementing STI/HIV prevention and care interventions for men who have sex with men in Senegal. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

iOanh KTH, Ashburn K, Pulerwitz J, Ogden J, Nyblade L. Improving hospital-based quality of care in Vietnam by reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

jEsu-Williams E, Schenk KD, Geibel S, Motsepe J, Zulu A, Bweupe P, et al. “We are no longer called club members but caregivers”: involving youth in HIV and AIDS caregiving in rural Zambia. AIDS Care 2006;18:888-94.

kSamuels F, Simbaya J, Sarna A, Geibel S, Ndubani P, Kamwanga J. Engaging communities in supporting HIV prevention and adherence to antiretroviral thereapy in Zambia. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ART = antiretroviral therapy

NGO = nongovernmental organization

STI = sexually transmitted infection

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Help institutions recognize stigma

Horizons and partners recognized from the outset that to improve the environment for people with HIV in health-care settings, it was important for management and health providers to acknowledge that stigma exists in their facilities. They found that a participatory approach that included ongoing sharing of data about levels and types of stigma in institutions helped build staff and management support for stigma-reduction activities.

In a study conducted in three public and private hospitals in New Delhi, India, hospital managers were initially unwilling to believe that stigma and discrimination were problems in their hospitals. Baseline data from interviews with health workers and HIV-positive patients as well as a survey of nearly 900 workers suggested otherwise.4 After the research team shared key findings, the hospital managers and staff developed action plans to address hospital workers' misconceptions about HIV transmission, as well as their judgmental attitudes and differential practices toward HIV-positive individuals. These action plans ultimately addressed limited supplies for practicing universal precautions, providers' needs for information and sensitization, and the lack of management support before the intervention.

To help develop the action plans and set institutional goals, the project team developed a checklist allowing hospital managers to examine how well their facility provides a safe working environment for staff and a welcoming environment for HIV-positive patients. During the evaluation of the intervention, the hospital managers reported that data on stigma and discrimination and use of the checklist showed them how HIV-positive patients were treated differently in their hospitals, and helped catalyze reform.4

Similarly, after baseline findings on stigma and discrimination were discussed as part of a hospital-based intervention study in Vietnam, hospital management became enthusiastic participants in subsequent intervention activities to improve care for people with HIV and safeguard the health of hospital workers.5 By proceeding gradually and involving staff in a non-confrontational manner, the intervention team was able to get institutional buy-in to make needed changes in policies and practices.

Address social stigma and the environment

The hospital-based intervention study in India focused on helping facilities establish an environment that provided timely, appropriate, and humane care for people with HIV. This required developing tailored interventions to protect the interests and well-being of both patients and staff. To catalyze social and environmental changes, the project team engaged hospital managers in a participatory process to develop action plans to address stigma. These action plans included establishing an HIV/AIDS care and management policy, enlisting people living with HIV to sensitize and train health-care workers, strengthening and mainstreaming HIV counseling, and developing and disseminating information on infection control procedures and the availability of post-exposure prophylaxis to staff.

After the intervention, health-care workers' attitudes about people with HIV and quality of care improved. For example, the proportion of health-care workers who, based on their scores on a stigma index, were categorized as having the least stigmatizing attitudes more than doubled (from 12% to 27%), and the proportion of respondents with the most stigmatizing attitudes declined considerably (from 24% to 7%). Counseling and testing practices and protection of patient confidentiality also improved, as did understanding and use of universal precautions with all patients.4

In Vietnam, Horizons and partners built on the results of the India study by conducting intervention research in four hospitals involving nearly 800 hospital workers. Activities included training for all cadres of hospital staff (e.g., nurses and janitors) on HIV and universal precautions, testimonials from people living with HIV as part of staff training workshops, participatory development of hospital policies, and key modifications of the structural environment (e.g., improved availability of hand-washing facilities and sturdy containers to dispose of needles and syringes). Two hospitals received these activities alone, while the other two received the same package of activities plus a half-day workshop focused on the causes and manifestations of social stigma, co-facilitated by people living with HIV.

Following the intervention, hospital practices improved, including significant declines in the labeling of patients' files and beds with their HIV status, a reduction in the overuse of barrier protections (e.g., using gloves during casual contact with HIV-positive patients), and better hospital-wide implementation of universal precautions. Health workers in all four participating hospitals significantly improved their mean scores on both fear-based and socially based stigma indices (p<0.05). While both interventions successfully reduced stigma, results from hospitals with the extra half-day staff workshop on social stigma showed more impact. For example, workers in these hospitals were 4.7 times less likely to report marking the files of HIV-positive patients (p<0.001) and 2.3 times less likely to report placing signs on beds indicating HIV status (p<0.001), compared with workers at the other two hospitals.5 To further illuminate the impacts of these promising intervention packages, it would be useful in future studies to separate and compare different components of these interventions.

Respond to the needs of stigmatized populations

In Brazil, formative research showed that truck drivers, a population often at increased risk of HIV infection, were wary of HIV services because of the stigma attached to accessing them.6,7 In response, Horizons and partners tested a model combining HIV-related services with other health services and targeted them to truckers. A health unit was established inside a border customs station in southern Brazil that provided a variety of services, including voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), syndromic management of STIs, and HIV/STI information, as well as basic health services not related to sexual health (such as blood pressure and glucose testing).

At baseline, less than half of the respondents had ever had an HIV test. By follow-up, the number of truckers who had ever had an HIV test increased by 49% in the intervention site, but only by 15% in the comparison site (p<0.01). The majority of participants reported that they found the services useful and nonstigmatizing.6

MSM are another highly stigmatized population in need of HIV services. In Senegal, Horizons and partners found that the stigma and discrimination suffered by many MSM results in the concealment of sexual behaviors from health-care providers, making it difficult for this population to receive appropriate STI services.8 The project team worked to create and train a network of health providers, sensitized to the special needs of MSM, who were available to provide confidential, nonjudgmental medical and psychosocial care. Qualitative findings at the end of the intervention period showed that men appreciated the availability of STI services, which they found to be of high quality and nonstigmatizing. According to a 23-year-old informant, “They are doing a wonderful job because they are available when we need them, and they are not judgmental.”9 Additional research is needed to determine whether these improvements in the health-care environment have led to an increased uptake of STI services.

Use the media to show that AIDS has a human face

In Nicaragua, Horizons helped evaluate a communication-for-social-change strategy that sought to empower young men and women to prevent HIV infection through critical discussion of social and cultural issues (e.g., stigma, gender inequality, and violence). To address these issues in an accessible and entertaining way, the project team created a national television soap opera series called “Sexto Sentido,” a youth-directed radio show, and various community-based activities (e.g., training of youth leaders and networking with other nongovernmental organizations [NGOs] to reinforce intervention messages and create advocacy networks).10

After following a representative cohort of more than 3,000 young people from three large cities over two years, researchers found that individuals with the highest level of exposure to the intervention were significantly less likely to hold stigmatizing attitudes than individuals with less exposure. After controlling for sociodemographic variables, the high-exposure group demonstrated a 20% greater reduction in stigmatizing attitudes (p<0.001) compared with the lower exposure group. Further, survey results indicated that the intervention resulted in a significant increase in knowledge and use of HIV-related services, as well as interpersonal communication about HIV prevention and sexual behavior. Qualitative data suggested that the soap opera reduced stigmatizing attitudes by helping viewers relate to affected individuals as human beings who have rights and need compassion and support.

The study also found that some aspects of stigma and discrimination are easier to change than others. For example, stigma against MSM and sex workers as vectors of HIV was resistant to change, even though other forms of stigma were significantly reduced among those exposed to the intervention. These results demonstrate the complexity of stigma as an intervention outcome and that one intervention strategy may not address all aspects of stigma and discrimination.10

A Horizons intervention study in Senegal found that the media contribute to the stigmatization of MSM by communicating negative and sensational stories about them. As part of its intervention activities, the project team held a workshop for media representatives in Dakar that included the participation of MSM, who brought a human face to the issues and helped journalists better understand the hidden realities of the men's lives, which are often punctuated by stigma, discrimination, and violence. Over the next 18 months, the project team reviewed local newspapers and found that no offensive or stigmatizing articles had been written about MSM.9

Involve people living with HIV in service delivery

Horizons has found that efforts to involve people with HIV in providing HIV services and in sensitizing other service providers about the realities of their lives empowers HIV-positive individuals, improves service delivery, and contributes to stigma reduction among health workers and community members. Studies in Burkina Faso, Ecuador, India, and Zambia revealed that when programs provide adequate support and training to HIV-positive team members, involvement in NGO activities can reduce their isolation, enhance their self-esteem, and improve community perceptions about their productivity. Further, involvement of people living with HIV can improve care and support services by making them more relevant and personalized. As one HIV-positive peer counselor in India noted, service recipients derive hope from seeing other HIV-positive individuals actively involved in delivering NGO services.11

The hospital-based stigma-reduction programs in Vietnam and India are other examples of successful collaborations with people living with HIV. In these interventions, health-care workers heard—often for the first time—from HIV-positive trainers about living with HIV, and began to relate to them as people, not just as patients.4,5

Engage the community

Horizons and partners have developed and tested different stigma-reduction strategies in the community. A Horizons study found that youth members of Zambian groups known as “anti-AIDS clubs” can be trained to provide care and support to people with HIV and help foster their acceptance within families and communities. The study examined young people in 30 anti-AIDS clubs who received training to become adjunct caregivers to families in their communities. They helped with domestic chores, bathed HIV-infected patients and dressed their wounds, and provided information, support, and referrals to family members. The study found that as a result of observing the activities of the youth caregivers and interacting with them, family members became more involved in their relative's care. After learning about the program and witnessing the work of the youth caregivers, community members began to see that they, too, could visit people with HIV. According to a client of the program, “Our community is beginning to accept people with AIDS since youth caregivers started visiting; they are not as fearful as before.”12 Future studies are needed to quantitatively evaluate changes in stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors resulting from youth caregiver initiatives.

Horizons and partners have also conducted quantitative evaluations of community-based stigma-reduction interventions. In Tanzania, a community-based organization trained its staff and volunteers (n=56), people living with HIV (n=24), and community leaders (n=10) to recognize stigma, integrate stigma reduction into their routine work, and carry out community sensitization and mobilization activities.

Findings from community surveys and the qualitative methods showed that recognition of HIV-related stigma (e.g., what it is and how it manifests) significantly increased over a two-year period, a key first step in the process of stigma reduction. There were also statistically significant differences in stigmatizing attitudes associated with shame and blame at end-line evaluation among those exposed and not exposed to the intervention activities. However, findings showed that the intervention did not reduce stigma community-wide. One explanation is that the intervention did not train enough people to saturate the study communities adequately enough to effect population-wide reductions in stigma. On the other hand, the researchers found that the stigma-reduction training had a profound effect on those trained, particularly the community leaders, leading to visible changes in their own behavior and leadership. A promising avenue for future efforts is equipping greater numbers of such opinion leaders with the skills and support necessary to reach more people.13

A study by Horizons and partners in Rwanda found that households without an adult caregiver are often stigmatized by the community, resulting in high levels of social exclusion and maltreatment. The project team developed and evaluated a volunteer adult mentorship program for youth-headed households to improve the psychosocial outcomes of its members. Analysis of pre- and post-intervention survey data collected from more than 1,300 youth household heads who did and did not participate in the adult mentorship program revealed significant improvements among participants.14

Using a six-item scale that explored perceptions of isolation and stigma from the community, the researchers found that over the course of the two-year study, participants reported lower levels of marginalization at follow-up compared with baseline, while there was no change among the comparison group. After controlling for background variables, an intervention effect was still evident. The researchers also found positive changes when examining the impact of the program on experiences of maltreatment, including sexual abuse, exploitation, and theft.14

Expand antiretroviral therapy (ART)

Horizons studies also support the idea that increased accessibility and uptake of ART has had a positive impact on stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors of community members and on internalized stigma (self-stigma or negative beliefs about themselves) among people living with HIV. In Zambia, in-depth interviews with people on ART in Lusaka and Ndola revealed a common perception that levels of stigma had dropped within the family and community, among health-care workers, and in the workplace. All respondents credited the increased availability of ART with reductions in stigma as well as increased awareness that becoming infected can happen to anyone and that almost everyone is somehow affected.15

These qualitative data support findings from a community survey that showed levels of stigmatizing attitudes decreased in the Lusaka and Ndola sites where there was either clinic-based or clinic- and community-based education about HIV and ART, as well as access to free treatment. Pre- and post-survey data among people on ART in Lusaka showed significant reductions in internalized and experienced stigma, which was measured using a 24-item scale adapted from the HIV stigma scale.16 But it is important to point out that there was no change in stigma levels in Ndola over time and that, despite statistically significant reductions in community-level stigma across the study sites, levels are still high enough to be of concern.

Findings from a Horizons study in Mombasa, Kenya, also found significant reductions in internalized stigma among a cohort of people taking ART and receiving adherence counseling. The research team measured internalized stigma with a 16-item scale, also adapted from the HIV stigma scale.16 Nearly three-quarters of respondents reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma at baseline, declining to 56% (p=0.001) after 12 months on treatment. The study also found that participants had disclosed their HIV status to a significantly greater number of family members after 12 months on treatment, from a median of two family members to a median of three at follow-up (p<0.001). However, there was no change in disclosure rates in the community or at the workplace. Interestingly, the Kenya study found that females had significantly higher levels of internalized stigma before initiating ART, but that this difference disappeared after a year on treatment.17 A similar pattern was observed in the Zambia study among cross-sectional samples of men and women who had just begun ART and among those interviewed two years later.15

ADDING TO THE EVIDENCE BASE ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HIV STIGMA AND PUBLIC HEALTH OUTCOMES

Through various Horizons studies, the quantitative relationship between stigma and public health outcomes was confirmed or elucidated. These associations highlight how stigma can be a major barrier to successful HIV prevention, care, and treatment programs. For example, findings from surveys administered to a random sample of 1,775 truck drivers in Brazil demonstrated that less stigmatizing attitudes and less fear of stigma were significantly correlated with VCT use (p<0.001), knowing where to get tested (p<0.001), and willingness to disclose HIV-positive test results (p=0.013).7 In India, survey data collected from hospital workers (884 doctors, nurses, and ward staff) indicated that higher scores on a stigma index—which focused on attitudes toward HIV-infected people—were associated with incorrect knowledge about HIV transmission and discriminatory practices. Examples of these practices included sharing the patient's HIV status with nontreating staff or with staff who did not directly interact with the patient, and the inappropriate use of gloves during casual contact with HIV-positive patients.18 A similar study in Vietnam, also in a hospital setting (n=795), found that approximately half (48%) of hospital workers reported that fear of HIV transmission and related stigmatizing attitudes led them to treat HIV-positive patients differently, such as by avoiding touching them or by avoiding them altogether.5

MEASURING THE MULTIPLE FACETS OF STIGMA

To address gaps in measurement, Horizons actively collaborated with other members of the U.S. Agency on International Development (USAID)-convened Stigma and Discrimination Indicator Working Group to develop quantitative measures of stigma. These measures were field tested in Tanzania19 and retested in a Horizons intervention study, also in Tanzania.13 Horizons and partners incorporated these measures and instruments into many of the studies described in this article, which took place in different settings (e.g., hospitals in India and Vietnam, and communities in Nicaragua and Tanzania). Horizons also collaborated with WHO to develop a generic survey tool designed to measure stigma and discrimination across multiple settings.20

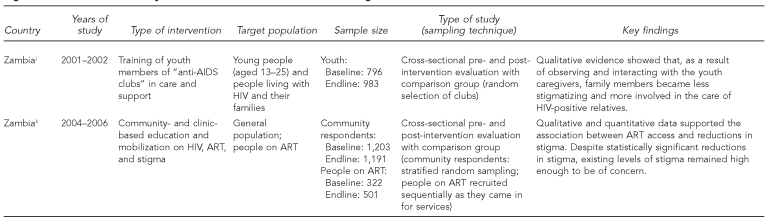

Measuring multiple dimensions or “domains” of stigma and discrimination is critical to accurately capturing existing stigma as well as changes due to an intervention. As part of Horizons' ongoing collaboration with partners (e.g., USAID and the International Center for Research on Women), four key dimensions of stigma have been articulated and tested:

Inappropriate fear of contagion: Measures focus on attitudes that reflect fear of contagion and HIV transmission from casual contact with people living with HIV.

Negative judgments about people living with HIV: Measures focus on attitudes that reflect blame, shame, and casting moral judgments on HIV-infected people.

Enacted stigma or discrimination: Measures encompass both interpersonal forms of discrimination (e.g., isolating or teasing people living with HIV) and institutional forms of discrimination (e.g., being fired from work or denied health care because of HIV).

Compounded stigma: Measures focus on perceptions of the association between HIV and certain (usually marginalized) groups, such as sex workers.

Horizons researchers focused on developing clear and precise survey items that can be used in multiple settings, and that measure each of these multiple dimensions of stigma and discrimination (Figure 2). Earlier instruments were limited by a focus on fear-of-contagion items, to the exclusion of measures of the social dimensions of stigma (i.e., negative or value-laden judgments about people with HIV). Demonstrating that all dimensions are relevant has had useful implications for developing appropriate intervention strategies. In India, the researchers developed and tested an index to measure the various dimensions of stigma in health-care settings, including attitudes about personal contact with HIV-positive people, blaming and judgmental attitudes, and support for discriminatory hospital practices. Baseline findings using the index helped inform the intervention, and comparisons with endline findings provided evidence of reductions in stigma in the hospital setting (Figure 2).4,18

Figure 2.

Examples of items for measuring different dimensions of stigma and discrimination

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

MOVING FORWARD

The Horizons portfolio has made substantial contributions to understanding HIV-related stigma and discrimination and finding ways to reduce it. Specifically, Horizons and partners have demonstrated that stigma is measurable, that intervention activities can be designed to address particular drivers of stigma, and that these interventions can reduce stigma among health workers and among family and community members, thereby contributing to improved quality of life for people living with HIV. The studies point to the positive role community organizations and the media can play in helping to empower HIV-infected individuals and change community perceptions about them. Horizons research also highlights the likely contribution of increased access to ART in reducing stigma among people living with HIV (internalized stigma) and in the general community.

However, given the magnitude of the problem, efforts to reduce stigma and measure the effects of interventions on stigma levels should become a higher priority among program managers, policy makers, and donors. The conceptual frameworks and measures developed under Horizons could be more widely used in the field to build a better understanding of how HIV programs and services influence stigma, both intentionally and unintentionally. It is also important not to neglect the types of hospital-based, community-based, media-focused, and institutional-level interventions in the Horizons portfolio that have demonstrated positive changes.

The field also needs more operations research to refine approaches and address gaps. More analytical studies of factors affecting stigma-reduction intervention outcomes are needed. For interventions that have shown promise, longitudinal studies and studies with measurements at one or more years after program completion would shed light on the durability of intervention effects over time. More research is also needed to understand the impacts of interventions from the perspective of people living with HIV, especially in health-care settings, and whether there are any differential impacts by gender, age, and other factors. Such information is critical for assessing whether stigma-reduction interventions have had a meaningful impact on those most affected. Stigma-reduction interventions with such marginalized and vulnerable populations as MSM and sex workers need to be further developed and evaluated. Also, efforts to better understand and address gender differences in internalized stigma and experiences of enacted stigma are needed.

More research should be carried out to understand the community-level effects of treatment expansion and what activities or conditions need to be in place to enhance the role of increased access to treatment vis-à-vis stigma reduction. The likely rapid expansion of male circumcision programs may also have implications for stigma; therefore, diagnostic and intervention research is necessary to ensure that men are able to make an informed choice about the procedure without fear of being stigmatized for their circumcision status. Finally, while measures of stigma and discrimination have been validated in specific local contexts, ongoing research is important to assess the validity and reliability of the measures across settings.

In conclusion, HIV-related stigma and discrimination remain key challenges to successful implementation of a host of HIV services and programs. Horizons projects have led to a better understanding of the causes of stigma, how stigma affects HIV prevention and care, how to measure stigma, and how best to reduce stigma and, thus, mitigate its impact.

Footnotes

The Horizons research studies reviewed in this article were conducted in collaboration with the following implementing and research partners, whose cooperation and input were vital: Sharan, Institute of Economic Growth, and Tata Institute of Social Sciences in India; Institute for Social Development Studies in Vietnam; International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), Population Council, Family Health International, and Tulane University School of Public Health in the United States; Puentos de Encuentro and Center for Demographic & Health Studies UNAN-Leon in Nicaragua; Rwanda School of Public Health and World Vision in Rwanda; Muhimbili University of the Health Sciences, Kimara Peer Educators, and Training Trust in Tanzania; International HIV/AIDS Alliance in the United Kingdom; Senegal National AIDS Control Program, Kimirina, CEPAR, INP+, and Cheihk Anta Diop University in Senegal; Care, Network for Zambian People Living with HIV and AIDS, Traditional Health Practitioners Association of Zambia, Family Health Trust, Mansa Catholic Diocese, and Institute of Economic and Social Research in Zambia; and International Centre for Reproductive Health in Kenya. The authors also thank Scott Kellerman, Naomi Rutenberg, and LeeAnn Jones of the Population Council; Laura Nyblade and Aparna Jain of ICRW; and Mary Ellsberg of Program for Appropriate Technology in Health, who provided key support in the development of this article.

These studies were made possible by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The contents of this article are the responsibility of the Population Council and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mann J. Statement at an informal briefing on AIDS to the 42nd Session of the United Nations General Assembly. New York: 1987. Oct 20, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahendra VS, Gilborn L, George B, Samson L, Mudoi R, Jadav S, et al. Horizons Final Report. New Delhi: Population Council; 2006. Reducing AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Indian hospitals. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oanh KTH, Ashburn K, Pulerwitz J, Ogden J, Nyblade L. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Improving hospital-based quality of care in Vietnam by reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinaglia M, Lippman SA, Pulerwitz J, de Mello M, Homan R, Díaz J. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Reaching truckers in Brazil with non-stigmatizing and effective HIV/STI services. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulerwitz J, Michaelis AP, Lippman SA, Chinaglia M, Diaz J. HIV-related stigma, service utilization, and status disclosure among truck drivers crossing the Southern borders in Brazil. AIDS Care. 2008;20:764–70. doi: 10.1080/09540120701506796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niang CI, Tapsoba P, Weiss E, Diagne M, Niang Y, Moreau A, et al. “It's raining stones”: stigma, violence, and HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men in Dakar, Senegal. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2003;5:499–512. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreau A, Tapsoba P, Ly A, Niang CI, Diop AK. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Implementing STI/HIV prevention and care interventions for men who have sex with men in Senegal. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solórzano I, Bank A, Peña R, Espinoza H, Ellsberg M, Pulerwitz J. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Catalyzing personal and social change around gender, sexuality, and HIV: impact evaluation of Puntos de Encuentro's communication strategy in Nicaragua. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horizons. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council and International HIV/AIDS Alliance; 2002. Greater involvement of PLHA in NGO service delivery: findings from a four-country study. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esu-Williams E, Schenk KD, Geibel S, Motsepe J, Zulu A, Bweupe P, et al. “We are no longer called club members but caregivers”: involving youth in HIV and AIDS caregiving in rural Zambia. AIDS Care. 2006;18:888–94. doi: 10.1080/09540120500308170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyblade L, MacQuarrie K, Kwesigabo G, Jain A, Kajula L, Philip F, et al. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Moving forward: tackling stigma in a Tanzanian community. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown L, Rice J, Boris N, Thurman T, Snider L, Ntaganira J, et al. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Psychosocial benefits of a mentoring program for youth-headed households in Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuels F, Simbaya J, Sarna A, Geibel S, Ndubani P, Kamwanga J. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Engaging communities in supporting HIV prevention and adherence to antiretroviral thereapy in Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:518–29. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaai S, Sarna A, Luchters S, Geibel S, Munyao P, Mandaliya K, et al. Horizons Research Summary. Nairobi: Population Council; 2007. Changes in stigma among a cohort of people on antiretroviral therapy: findings from Mombasa, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahendra VS, Gilborn L, Bharat S, Mudoi R, Gupta I, George B, et al. Understanding and measuring AIDS-related stigma in health care settings: a developing country perspective. SAHARA J. 2007;4:616–25. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyblade L, MacQuarrie K. Current knowledge about quantifying stigma in developing countries. Washington: USAID, POLICY Project, and International Center for Research on Women; 2006. Can we measure HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination? [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obermeyer CM, Bott S, Carrieri P, Parsons M, Pulerwitz J, Rutenberg N, et al. HIV testing, treatment and prevention: generic tools for operational research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]