SYNOPSIS

In the field of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention, there has been increasing interest in the role that gender plays in HIV and violence risk, and in successfully engaging men in the response. This article highlights findings from more than 10 studies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America—conducted from 1997 through 2007 as part of the Horizons program—that have contributed to understanding the relationship between gender and men's behaviors, developing useful measurement tools for gender norms, and designing and evaluating the impact of gender-focused program strategies. Studies showed significant associations between support for inequitable norms and risk, such as more partner violence and less condom use. Programmatic lessons learned ranged from insights into appropriate media messages, to strategies to engage men in critically reflecting upon gender inequality, to the qualities of successful program facilitators. The portfolio of work reveals the potential and importance of directly addressing gender dynamics in HIV- and violence-prevention programs for both men and women.

In the mid-1990s, the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo and the International Conference on Women in Beijing called global attention to the importance of involving men in reproductive health programs because of their influence on women's health, including women's ability to protect themselves from infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1–3 But not long after these seminal meetings, researchers and health advocates also began to highlight the benefits for men when programs and policies address their reproductive and sexual health needs and encourage more equitable sexual decision-making.4,5

When the Horizons program began in 1997, there was some activity, primarily from nongovernmental organizations, to foster more gender-equitable relationships between men and women, and reach men with information and services. As these efforts multiplied, the need to better understand the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of programming targeted to men also grew. To fill this knowledge gap, Horizons and partners in Latin America, Asia, and Africa developed and implemented several intervention studies. This article summarizes the major contributions of the Horizons program's gender and HIV-prevention portfolio to understanding the relationships between gender norms and men's behaviors, and the impact of interventions designed to affect change on these attributes.

WHY GENDER MATTERS

Early in life, both boys and girls internalize societal messages about how males and females are supposed to behave. Often, these behavioral norms promote unequal gender roles and responsibilities, which can encourage behaviors that place men and their sexual partners at risk of various negative health outcomes, including HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).5–7 Examples of such norms for men include initiating sexual activity early in life, having multiple sexual partners, and representing themselves as knowledgeable about sexual matters and disease prevention even when they are not.6,8,9

Gender norms that put men in a position of sexual dominance also limit women's ability to control their own reproductive and sexual health. One example is the belief that it is the man's responsibility to acquire condoms, as a young woman who has her own condoms might be seen as promiscuous.10 Another is that males must be seen to know more about sex than females, who must project an aura of innocence.11 Gender-based power dynamics exacerbate these issues and frequently result in women having less power than men in sexual relationships. Consequently, women often cannot negotiate protection, including condom use, and have less say over the conditions and timing of sex—factors that put them at a disadvantage in terms of HIV/STI risk.12–14

Male violence against women, an extreme manifestation of gender inequality, is the direct result of gender norms that accept violence as a way to control an intimate partner. Men's use of violence against women and girls is a human rights violation that makes it impossible to initiate and maintain HIV-protective behaviors. A multi-country study found that between one-fifth and one-half of women of reproductive age have experienced physical violence by a male partner.15 Data from a South African study found intimate partner violence to be significantly associated with HIV seropositivity among women attending antenatal care centers.16

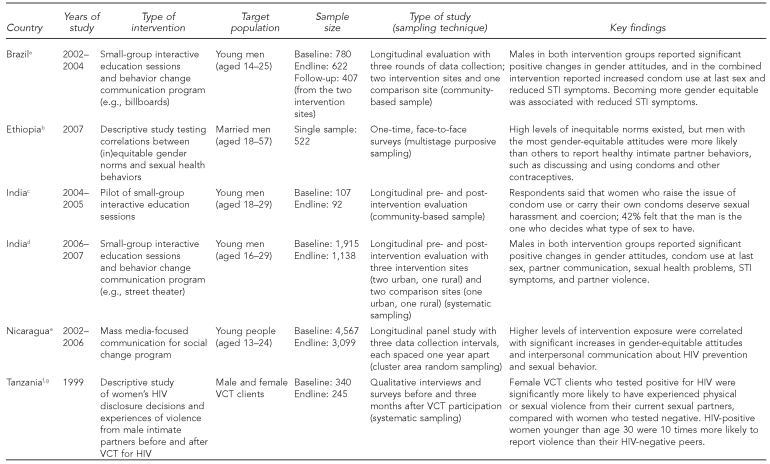

Despite growing awareness that changing inequitable gender norms is key to realizing sexual and reproductive health, including HIV prevention,11,17,18 relatively few interventions had explicitly attempted to address these norms, and even fewer studies had measured the effects of such interventions. Additionally, most reproductive health interventions had focused primarily on women, with little attention paid to men.19 To respond to these needs, the Horizons program collaborated with international partner organizations to develop, implement, and evaluate interventions that engage men in reproductive health decision-making and promote gender-equitable attitudes and behaviors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of Horizons studies related to gender norms and HIV risk, 1999–2007

aPulerwitz J, Barker G, Segundo M, Nascimento M. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2006.

bMiddlestadt S, Pulerwitz J, Nanda G, Acharya K, Lombardo B. Gender norms as a key factor that influences SRH behaviors among Ethiopian men, and implications for behavior change programs [unpublished manuscript]. Washington: Academy for Educational Development; 2007.

cVerma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, et al. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reprod Health Matters 2006;14:135-43.

dVerma R, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra VS, Khandekar S, Singh AK, Das SS, et al. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

eSolórzano I, Bank A, Peña R, Espinoza H, Ellsberg M, Pulerwitz J. Catalyzing personal and social change around gender, sexuality, and HIV: impact evaluation of Puntos de Encuentro's communication stategy in Nicaragua. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

fMaman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan M, Kilonzo G, Sweat M, Weiss E. HIV and partner violence: implications for HIV voluntary counseling and testing programs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Washington: Population Council; 2001.

gMaman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss E, et al. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: findings from a voluntary counseling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1331-7.

hMaman S, Mbwambo J. Evaluation of a community-based HIV and violence prevention intervention targeting young men in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [unpublished manuscript]. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

iMarindo R, Weiss E, Pulerwitz J. Promoting male involvement and HIV prevention during pregnancy in Zimbabwe. Washington: Population Council; 2004.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STI = sexually transmitted infection

VCT = voluntary counseling and testing

Diagnosing the problem

To effectively address gender norms that contribute to HIV/STI risk, Horizons' first task was to better understand men and women's beliefs and experiences about masculinity, gender, and sexuality; to identify inequitable gender norms prevalent in study communities; and to determine whether male support for them correlates with negative HIV-related outcomes such as unprotected sex and STI symptoms.

In Brazil, Horizons and partners built on qualitative research conducted with young men in a low-income community20 that revealed a prevailing version of masculinity characterized by limited male involvement in reproductive health and child care, a sense of male entitlement to sex from women, and tolerance of violence against women. Still, a minority of more “gender equitable” men were described, who sought relationships built on intimacy and equality, were involved fathers, assumed some responsibility for reproductive health issues, and did not use violence in intimate relationships. These findings, plus experience gained by Horizons researchers from developing measurement tools for gender-based power dynamics,13,21 informed the development of survey items to assess the extent to which young men were “gender equitable.” These items clustered around four domains: (1) sexual relationships, (2) domestic chores and daily life, (3) reproductive health and disease prevention, and (4) violence. When used with a similar population of young men as part of an intervention study, baseline results showed that more than half of the respondents agreed with the statement, “Men need sex more than women do,” more than a third believed that “Changing diapers, giving kids a bath, and feeding kids are the mother's responsibility,” and about one-fourth “would be outraged if my wife asked me to use a condom.”22

Horizons and partners also explored issues around masculinity in India.23 When asked about the qualities of a “real man,” young male informants identified dominance, expressed as physical and verbal aggression directed toward other men and women. They also felt that a real man should be virile and not have feminine mannerisms, and noted that such sexually provocative and coercive behaviors as making derogatory comments, whistling, jostling, and unwanted touching are commonly used by men to demonstrate sexual power. An ideal woman was defined as one who does not respond to men's sexual advances and is therefore marriageable. The informants said that women who raise the issue of condom use or carry their own condoms deserve sexual harassment and coercion. In addition, using an instrument similar to that used in the Brazil study, 42% felt it was the man who decides what type of sex to have, and more than a third believed that a man should have the final word about decisions in the home, a woman should tolerate violence to keep her family together, and it is a woman's responsibility to avoid getting pregnant. At the same time, there was support for some equity in relationships, with 85% agreeing with the statement, “A couple should decide together if they want to have children.”

In Ethiopia, researchers examined similar domains among urban and rural married men.24 As in Brazil and India, Horizons and partners found that many men supported inequitable norms related to gender roles. About half felt that a woman should not initiate sex, that a woman should obey her husband in all things, and that a woman doesn't deserve respect if she has had sex before marriage. Nearly a third felt that women who carry condoms on them are easy. And about one-quarter or more of male survey respondents agreed with each of six items supporting violence against intimate partners. For example, 23% of men agreed with the statement, “There are times when a woman deserves to be beaten,” and 59% felt that a woman should tolerate violence to keep her family together.

In Tanzania, qualitative research revealed the interrelationship between violence against female partners—a pernicious example of gender inequality—and infidelity. Horizons and partners found high levels of infidelity among young couples and found that infidelity—or the perception of it—is the most common trigger for violence, condoned by many men and some women. For men, violence is justified when women lie to their partners and must be “taught” right from wrong. According to one informant, “There's time they need a teaching.” There was also widespread acknowledgement that women expect men to provide economic support as part of a sexual relationship and will use sex as a way to remedy resource constraints. Respondents said that women expect their male partners to provide them with money and gifts, but mistrust men because they often make false promises to have sex. On the other hand, men mistrust women's intentions, concerned that women's primary motivation for the relationship is financial support.25

Due to high levels of infidelity and the transactional nature of many sexual interactions, many male and female young people in the Tanzanian study distrusted their sexual partners and accepted partner violence as the norm. Findings from a quantitative survey of young men in the same communities revealed that more than a third agreed there is nothing a woman can do if her partner wants to have other girlfriends, and about half believed that a woman should tolerate beatings to keep the family together.26

Acceptance of violence against women was also common among women surveyed at a Tanzanian voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) center. Almost half of surveyed females identified at least one situation in which they felt that physical punishment of women was justified.27 Such situations included disobedience, infidelity, refusing sexual relations, and not performing household chores to the satisfaction of male partners. Female VCT clients who tested positive for HIV were also significantly more likely to have experienced physical or sexual violence from their current sexual partners, compared with women who tested negative. In fact, HIV-positive women younger than age 30 were 10 times more likely to report violence than their HIV-negative counterparts.28

Horizons research has found that gender norms limit male participation in HIV and reproductive health services geared to women, which has implications for women and children's health outcomes. Horizons researchers conducted an evaluation study of United Nations-supported programs in 11 countries, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, on prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV.29 In most of the pilot settings, male involvement and support were recognized as critical, but challenging, to improving women's uptake of core PMTCT services, including deciding to be tested, returning for test results, taking antiretroviral drugs correctly, and choosing and carrying out an infant feeding method. The evaluation found some efforts in these programs to engage and educate men to get their support for PMTCT services, but more could be done.

Male involvement during pregnancy is also critical for HIV prevention. Pregnancy can be a particularly vulnerable time for women because of high HIV prevalence among individuals of childbearing age, social norms that may condone extramarital partners for men while their wives are pregnant, and low or no use of condoms in marriage.30–32 However, pregnancy may also provide an opportunity to foster communication within couples by capitalizing on both members' interest in the physical and social well-being of the mother and child. A Horizons study in Zimbabwe found that female respondents expected men to be more involved in pregnancy than the men themselves intended to be; while the men focused on financial support and passive involvement, the women also expected emotional support, accompaniment to antenatal appointments, and help with domestic chores. The researchers found that gender norms that frame pregnancy as a woman's domain and the pervasiveness of unwelcoming clinic environments for men who accompany their wives to care are barriers to male involvement in antenatal care.33

Several Horizons studies also showed significant correlations between support for inequitable gender norms and risk for HIV and other STIs. For example, young men from rural sites in India who supported inequitable gender norms were significantly more likely in the last three months to have had sex with more than one partner, been physically or sexually abusive against a partner, and reported sexual health problems, including STI symptoms.34 Likewise, in Brazil, endorsement of inequitable gender norms was significantly associated with reported STI symptoms, less contraceptive use, and both physical and sexual violence against a current or recent partner.22 Horizons and partners also found evidence that equitable gender attitudes could be protective: in the Ethiopia study, men with gender-equitable attitudes were more likely to report healthy intimate partner behaviors, such as discussing and using condoms and other contraceptives.24

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

The findings described previously helped inform the intervention strategies that Horizons and partners developed and evaluated. Specifically, results from these studies demonstrate the importance of engaging men as partners in challenging inequitable gender norms in their communities, of facilitating critical reflections on gender inequality and its impacts on the lives of both women and men, and of helping men take on more proactive roles in the traditionally female domains of reproductive and antenatal health care. This section highlights selected findings and insights from intervention studies that Horizons and partners implemented over the course of the program.

Engage men in thinking critically about gender inequality

In Brazil, researchers investigated the impacts of interactive group education sessions for young men and a community-wide “lifestyle” social marketing campaign that used gender-equitable messages to promote safer sex and healthier relationships—called Program H (for men, or homens in Portuguese).22 Activities in the group education sessions included role-plays, brainstorming exercises, discussions, and individual reflection, led by adult male facilitators. Both the group sessions and the social marketing campaign aimed to promote critical thought on gender norms by encouraging young men to reflect on how they act as men, while also enjoining them to respect their partners, avoid using violence against women, and practice safer sex.22 The three-arm study encompassed a group education-only arm, a combination of group education sessions and a social marketing campaign arm, and a delayed intervention arm that served as the control.

Qualitative data from intervention participants demonstrate the effectiveness of helping young men actively reflect on the ways that gender inequality plays out in their own lives. For example, one young man described a new perspective on how his actions may affect his partners:

Before [the workshops] I had sex with a girl … and then left her. If I saw her later, it was like I didn't even know her. If she got pregnant or something, I had nothing to do with it. But now, I think before I act or do something.22

Quantitative data also show the effectiveness of engaging men to reflect critically on their roles and relationships. Support for inequitable gender norms significantly decreased post-intervention in both intervention groups, while no corresponding change was seen in the control group.22 The changes made by young men in the intervention groups were maintained six months after the end of activities. Moreover, for the two intervention sites, reported condom use with primary partners increased, STI symptoms were reduced, and decreases in agreement with inequitable gender norms during one year were significantly associated with decreased reports of STI symptoms.

In India, a modified version of the Brazil intervention resulted in significant reductions in support for inequitable gender norms among men in urban and rural communities. Depending on the study site, males in the intervention groups also reported significant positive changes in reported condom use at last sex, partner communication, sexual health problems (including STI symptoms) and partner violence. Intervention participants spoke of the value of critically reflecting on gender roles and relationships:

After the session of gender and discussions with the peer leaders, I realized the importance of my wife. Slowly, slowly I started discussing with her, started helping with her work, and this has created more love and affection. I started respecting her and one day she requested me to keep away from my girlfriends … I have accepted it.34

Focus interventions on younger men

Horizons studies highlight the feasibility and effectiveness of focusing interventions to change gender norms on young men as they are starting to develop intimate romantic and sexual relationships for the first time. For example, young men participating in the group education sessions in Brazil reported that they appreciated the sessions because they learned new information about sexuality and about the female reproductive system—such as the fertile period—as well as about women's sexual pleasure.22

Adolescence is also a time when gender role differentials widen,35 as boys begin to enjoy privileges and freedoms reserved for men. While boys and young men often have greater mobility and opportunities compared with their female peers, these advantages also create vulnerabilities for men. For example, young men may face peer pressure to engage in unprotected sexual relationships as proof of their manliness and sexual prowess.34 Interventions that reach young men during adolescence and early adulthood have the potential to provide a needed counterbalance to such pressures.

Include interactive, small-group sessions and community-based activities

Horizons studies demonstrated the effectiveness and feasibility of interactive, small-group education sessions to promote more equitable gender norms among young men. In both Brazil and India, small-group sessions used interactive exercises to cover such topics as gender and sexuality; STI/HIV risk and prevention; partner, family, and community violence; the reproductive system; alcohol and risk; and HIV-related stigma and discrimination.22,34 In both of these settings, the group education activities were implemented during regular (often weekly) meetings over the course of four to six months, allowing substantial time for young men to develop rapport and trust with each other and the group facilitators. In India, the sessions prompted intense debate and discussions, and young men often drew examples from their own life experiences, an indicator of the relevance of the methodology and the themes for their personal lives.34

Facilitators of the group sessions in Brazil perceived that it was important for the young men to participate in male-only groups, safe spaces to openly address various key topics. The young men appreciated the opportunity “to be here among men and to be able to talk,”22 as one participant noted:

We are learning a lot in the workshops and have never participated in this type of program in which we can talk openly about various issues and our doubts about health, sexuality, and STDs.22

In Brazil, the positive changes supporting equitable gender norms were equally great for young men exposed to the combination of group education activities and the community-based social marketing campaign, and for the group participating only in group education activities. However, it was only the combined intervention that led to significant changes in some of the HIV-related outcomes (e.g., increased condom use).22 In India, both arms of the intervention (group education sessions alone, and group sessions plus a community-based campaign that included street theater) led to significant positive changes in gender norms and HIV-related outcomes.34 No positive changes were found among the control groups in either Brazil or India. These findings underscore the success of the group education sessions at addressing often deep-seated and complex gender-related norms, plus the additional impact of community-based activities to reinforce the HIV-prevention messages with a gendered perspective.

Use the media to promote gender equity and HIV prevention

In Nicaragua, Horizons and partners evaluated a communication-for-social-change strategy targeting young people that encouraged responsible sex, open communication about sensitive topics, condom use, and empowerment of women. The project aimed to foster critical discussions about social and cultural issues that hinder HIV prevention among young people, such as gender inequity, partner violence, and stigma and discrimination. The intervention sought to address these issues in an accessible and entertaining television soap opera series called Sexto Sentido, which included characters who modeled gender-equitable behaviors related to sexual health and relationships, partner violence, and women's status. The intervention also included a youth-directed radio show and various community-based activities (e.g., youth camps).36

After following a representative cohort of 3,099 young people aged 13 to 24 from three large cities over two years, the researchers found that overall support for gender-equitable norms increased over time. But individuals with the highest level of exposure to the intervention became significantly more “gender equitable” compared with those with lower levels of exposure. For example, young people with the greatest exposure were significantly more likely than others to agree that there is no justification for a man to hit his wife. There was also an increase in knowledge and use of HIV-related services and a significant increase in interpersonal communication about HIV prevention and sexual behavior.36 These findings suggest that communication-for-social-change programs can be an efficient strategy both for reaching large numbers of young people and for effecting measurable change in gender attitudes and norms on a population level.

Reach men directly when their partners are pregnant

Because pregnancy is often viewed as a female domain, involving men in antenatal care and PMTCT services can be formidable, but providing information directly to men has promise as an intervention. In an intervention in Kenya, program staff talked about PMTCT of HIV with men rather than through women, inviting men to the clinic for HIV testing, community education on PMTCT in places where men congregate, and support groups for men.29 These strategies led to significant increases in HIV-related discussions between female clients and their regular partners, HIV testing of male partners of PMTCT clients, and disclosure of HIV results by both women and men to a regular partner.

A Horizons study in Zimbabwe also explored whether promoting male involvement in their partners' pregnancy and in antenatal care would result in couples practicing HIV/STI protective behaviors.33 The intervention included community outreach, male-oriented educational materials, a group talk to antenatal clinic clients, and couples counseling by nurse midwives. Of all the intervention components, outreach activities showed the most promise, successfully promoting community discussions and personal reflection about male involvement and sexual health. Community health workers conducted the outreach activities, which included such interactive strategies as picture cards, role-playing, posters, and flash cards. Couples counseling was the weakest component of the intervention, due to counselor attrition, limited participation by male partners, and the difficulty of counseling on sensitive topics. Despite these challenges, the nurse midwives felt there was a need for providing information and counseling to couples because often only one member was HIV-positive or infected with another STI.

Inequitable and equitable attitudes often coexist

Findings from Horizons studies indicate that certain key inequitable beliefs may coexist with generally equitable norms. For example, in the Brazil study, some young men reported respect for and repudiated violence against women, and believed they should use condoms and discuss condom use with their partners, while concurrently reporting that men have a right to have outside sexual partners.22 In the Nicaragua study, while the sample overall moved in the direction of greater gender equity, some attitudes did not change. For example, while there was less support at the end of the intervention for the statement, “Women who carry condoms are easy,” the notion that men should have greater control over sexual relations did not change.36 These examples highlight the inherent complexities of gender: some facets may be easier to change than others, and certain intervention strategies may be more appropriate for changing some norms than others.

MEASURING GENDER EQUITY

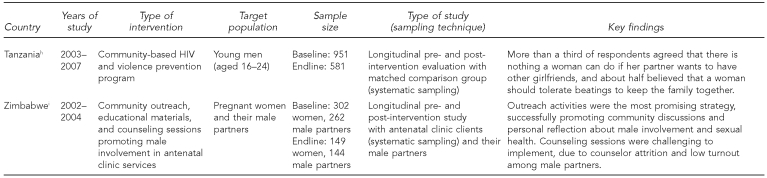

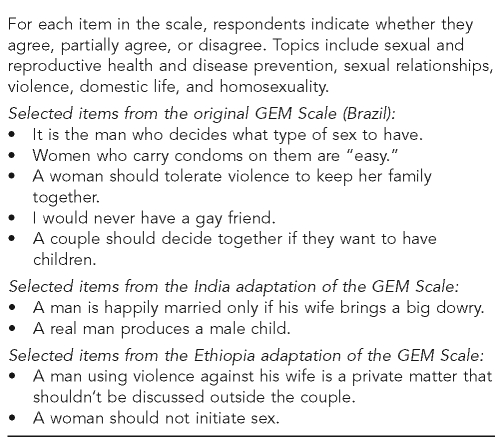

Before Horizons researchers began their work, few studies had attempted to quantitatively measure change in attitudes about gender norms, and few scales were available to evaluate an intervention's effects on gender norms and sexual risk behaviors. In response to this important gap, Horizons researchers developed and validated the Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale.37 This scale includes items on women's and men's roles in domestic work and child care, sexuality and sexual relationships, reproductive health and disease prevention, violence, and homophobia and relations between men. Items were based on previous qualitative work and a literature review, and initially administered to a household sample of 742 men aged 15 to 59 years in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Factor analyses supported two subscales, and the scale was internally consistent (alpha = 0.81). As hypothesized, more support for equitable norms (i.e., higher GEM Scale scores) was significantly associated with less self-reported partner violence, more contraceptive use, and a higher education level.

Figure 2 displays examples of items from the original 24-item GEM Scale developed in Brazil and from subsequent adaptations of the scale for India34 and Ethiopia,24 where a few items were added (or removed) in each context for cultural specificity. Additional psychometric testing took place in both India and Ethiopia, and the adapted scales were found to be clear and useful, internally consistent, and associated with key outcomes as expected. In addition to Horizons studies, the GEM Scale is being used by researchers in such countries as Mexico, Kenya, Uganda, and Thailand to study different populations of males and females.

Figure 2.

The Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale

In addition to the GEM Scale, we evaluated the programs with indicators that are commonly used in the HIV-prevention field, such as communication between partners about HIV, and condom use. In the case of condom use, for example, depending upon the appropriateness for the particular study and intervention period, measures included “condom use at last sex (with a primary or secondary partner)” and “consistent condom use over a period of one to six months (with a primary or secondary partner).” Utilizing the GEM Scale alongside more traditional measures has been an effective strategy for obtaining nuanced, quantitative information on program impacts.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND PROGRAM PRIORITIES

Horizons operations research findings reveal that gender noms can play a powerful role in facilitating and condoning HIV risk behaviors, and that strategies fostering equitable gender norms should become part of HIV-prevention programs. The studies conducted by Horizons and partners provide evidence for the effectiveness of group education interventions that involve high levels of participant interaction, critical reflection, and engagement. These studies also highlight the promise of mass media communication programs to raise awareness, spark dialogue about gender norms and sexual health, and increase gender-equitable attitudes among men. Both small-group sessions (with their intensive impact on limited numbers of individuals) and mass media communications strategies (with their less intensive but broader reach) have a place in future efforts to increase equitable norms and improve sexual and reproductive health among men and women alike.

While the past decade of Horizons' work on gender equity and HIV prevention has focused on investigating programs that specifically target men, there is also a need to evaluate intervention strategies that involve both men and women. This work continues in India and Brazil, where parallel programs informed by the Horizons studies have been developed for girls and women that focus on promoting self-efficacy and self-esteem. Evaluations of different combinations of intervention activities for women, men, and both together are ongoing. Integrating both women and men as active partners in future interventions is likely to be a useful strategy for improving communication, collaboration, and mutual support between male and female participants. At the same time, the value of all-male and all-female initiatives should not be discounted, because they fill a particular role in providing “safe” spaces for men and women to express worries, share their personal stories, and seek advice.

Further, it would be important to reach younger adolescents with gender-focused programming as well, as gender norms are incorporated and reinforced early in life. Interventions targeted at adolescents could also bridge generation gaps by involving key role models, such as fathers and teachers. Currently, the GEM Scale is being adapted for younger age groups, and several gender norms studies are underway with children aged 12 to 16 years in Brazil and India.

Future initiatives should also explore possibilities for programs that target gender norms in different settings and scale up success stories, and should evaluate adaptations of programs and the process of scale-up. In addition, future evaluations should consider adding other types of outcome indicators, such as biomarkers that track acquisition of STIs, to supplement self-reported data. Strategies such as the small-group educational workshops about gender norms could be inexpensively and efficiently integrated into many existing programs, such as school-based and community-based HIV education activities, voluntary counseling and testing initiatives, and support services for people living with HIV. In the process of integrating these kinds of initiatives into general HIV services, it is important for program implementers to include such effective interactive group activities as role-playing, debating, and sharing personal stories.

Finally, it is important to build programs that support long-term, sustained change in gender norms by fostering broad-based, ongoing discussion on manhood, masculinity, and gender dynamics. Changing attitudes and behaviors is a complex and gradual process. The status quo supports male dominance, and both men and women are often unaware that these gender inequities even exist. Only a long-term strategy that includes a variety of approaches can successfully promote and support such changes.

Footnotes

The Horizons research studies reviewed in this article were conducted in collaboration with the following implementing and research partners, whose cooperation and input were vital: Instituto PROMUNDO in Brazil; CORO for Literacy, MAMTA, and DAUD in India; Miz-Hasab Research Center in Ethiopia; Muhimbili University and the University of Dar es Salaam Drama Department in Tanzania; the Center for Communication Programs, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the Academy for Educational Development in the United States; Puntos de Encuentro and CIDS/UNAN Leon in Nicaragua; and the University of Zimbabwe in Zimbabwe. In addition, the authors thank Scott Kellerman, Naomi Rutenberg, and LeeAnn Jones for their assistance in preparing this article.

These studies were made possible by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The contents of this article are the responsibility of the Population Council and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations Population Information Network. International Conference on Population and Development; 1994; Cairo, Egypt. [cited 2008 Mar 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.un.org/popin/icpd2.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women. Fourth World Conference on Women; 1995; Beijing, China. [cited 2008 Mar 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene ME, Mehta M, Pulerwitz J, Wulf D, Bankole A, Singh S. Involving men in reproductive health: contributions to development[background paper to the report Public Choices, Private Decisions: Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals] New York: United Nations Millennium Project; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker G Department of Child and Adolescent Health, World Health Organization. What about boys? A literature review on the health and development of adolescent boys. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivers K, Aggleton P. Men and the HIV epidemic, gender and the HIV epidemic. New York: United Nations Development Programme, HIV and Development Program; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell CA. Male gender roles and sexuality: implications for women's AIDS risk and prevention. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00322-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:539–65. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsiglio W. Adolescent male sexuality and heterosexual masculinity: a conceptual model and review. J Adolesc Res. 1988;3:285–303. doi: 10.1177/074355488833005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris L. Determining male fertility through surveys: young adult reproductive health surveys in Latin America; Presented at the International Population Conference; 1993 Aug 24–Sep 1; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childhope. Gender, sexuality and attitudes related to AIDS among low-income youth and street youth in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. New York: Childhope; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss E, Whelan D, Gupta GR. Gender, sexuality and HIV: making a difference in the lives of young women in developing countries. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2000;15:233–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaro H. Love, sex, and power. Considering women's realities in HIV prevention. Am Psychol. 1995;50:437–47. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;14:789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mane P, Gupta GR, Weiss E. Effective communication between partners: AIDS and risk reduction for women. AIDS. 1994;8(Suppl 1):S325–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Population reports: ending violence against women. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program; 1999. Center for Health and Gender Equity. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Exner TM, Dworkin SL, Hoffman S, Ehrhardt AA. Beyond the male condom: the evolution of gender-specific HIV interventions for women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:114–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:13–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pile JM, Bumin C, Ciloglu GA, Akin A. Involving men as partners in reproductive health: lessons learned from Turkey. AVSC Working Paper No. 12. 1999. Jun, [cited 2008 Jan 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.engenderhealth.org/pubs/workpap/wp12/wp_12.html.

- 20.Barker G. Gender equitable boys in a gender inequitable world: reflections from qualitative research and programme development in Rio de Janeiro. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2000;15:263–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, De Jong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pulerwitz J, Barker G, Segundo M, Nascimento M. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2006. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, et al. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:135–43. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middlestadt S, Pulerwitz J, Nanda G, Acharya K, Lombardo B. Gender norms as a key factor that influences SRH behaviors among Ethiopian men, and implications for behavior change programs. Washington: Academy for Educational Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lary H, Maman S, Katebalila M, McCauley A, Mbwambo J. Exploring the association between HIV and violence: young people's experiences with infidelity, violence and forced sex in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:200–6. doi: 10.1363/3020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maman S, Mbwambo J. Evaluation of a community-based HIV and violence prevention intervention targeting young men in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Washington: Population Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan M, Kilonzo G, Sweat M, Weiss E. HIV and partner violence: implications for HIV voluntary counseling and testing programs in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Washington: Population Council; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss E, et al. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: findings from a voluntary counseling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1331–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutenberg N, Baek C, Kalibala S, Rosen J. Evaluation of United Nations-supported pilot projects for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: overview of findings. New York: UNICEF; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foss AM, Hossain M, Vickerman PT, Watts CH. A systematic review of published evidence on intervention impact on condom use in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:510–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marindo R. Sexual behaviour during pregnancy in urban Harare. Harare (Zimbabwe): Centre for Population Studies, University of Zimbabwe; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onah HE, Iloabachie GC, Obi SN, Ezugwu FO, Eze JN. Nigerian male sexual activity during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76:219–23. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marindo R, Weiss E, Pulerwitz J. Promoting male involvement and HIV prevention during pregnancy in Zimbabwe. Washington: Population Council; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verma R, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra VS, Khandekar S, Singh AK, Das SS, et al. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruce J, Lloyd CB, Leonard A. Families in focus: new perspectives on mothers, fathers, and children. New York: Population Council; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solórzano I, Bank A, Peña R, Espinoza H, Ellsberg M, Pulerwitz J. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Catalyzing personal and social change around gender, sexuality, and HIV: impact evaluation of Puntos de Encuentro's communication stategy in Nicaragua. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM Scale. Men and Masculinities. 2008;10:322–38. [Google Scholar]