SYNOPSIS

An estimated 430,00 new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections occurred among children younger than 15 years of age in 2008, most in sub-Saharan Africa and most due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). In marked contrast, MTCT of HIV has been virtually eliminated in well-resourced settings through the use of combinations of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for the mother during pregnancy and labor and for the infant postpartum; cesarean delivery to reduce the infant's exposure to trauma and infection in the birth canal; and formula feeding to protect the infant from transmission from breastfeeding. While effective, these interventions are costly and require strong health-care systems. From 1999 to 2003, Horizons conducted operations research to determine how interventions successful in the clinical trial setting would translate to the real-world environments of maternal and child health-care delivery in low-resource settings. A second set of Horizons studies (2004–2007) sought to address gaps in adherence to ARV prophylaxis; examine roles of family planning in prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) programs; show the value of psychosocial support for HIV-positive mothers; and identify ways to improve the quality of care and follow-up for women in the postpartum period. This article provides an assessment of the findings of Horizons studies on PMTCT interventions from 1999 to 2007 and identifies needs for follow-on efforts.

An estimated 430,00 new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections occurred among children younger than 15 years of age in 2008,1 most in sub-Saharan Africa and most due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). In marked contrast, MTCT of HIV has been virtually eliminated in well-resourced settings such as the United States and Europe through the use of combinations of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for the mother during pregnancy and labor and for the infant postpartum; cesarean delivery to reduce the infant's exposure to trauma and infection in the birth canal; and formula feeding to protect the infant from transmission from breastfeeding.2 While effective, these interventions are costly and require strong health-care systems.

In the late 1990s, breakthrough clinical trials of shorter and less expensive ARV regimens—a short course of azidodeoxythymidine (AZT) for the mother or a single dose of Nevirapine to mother and infant—demonstrated reductions of about 50% in vertical transmission of HIV.3,4 These advances made prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) an affordable prospect in sub-Saharan Africa and other resource-constrained settings.

Based on these clinical trial results, PMTCT pilot programs were designed and implemented in 11 developing countries under the leadership of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). These pilots, introduced in 1999, included voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), provision of short-course prophylaxis for HIV-positive pregnant women, and counseling on infant feeding. The new HIV services took advantage of existing infrastructure and were added to programs in antenatal care (ANC), obstetric care, family planning, and maternal and child health clinics.

During this early stage of program implementation, Horizons conducted operations research to determine how interventions successful in the clinical trial setting would translate to the real-world environments of maternal and child health-care delivery in low-resource settings. It was unknown, for instance, whether testing pregnant women for HIV was feasible or culturally acceptable given the stigma and fear associated with a positive diagnosis, particularly because antiretroviral therapy (ART) was not then available for women testing positive in these settings. Also unknown was whether the offer of short-course ARV drugs outside of a controlled clinical trial setting would yield similar results in reducing MTCT: would women routinely return to the clinic to get refills of medication and adhere to the twice-a-day regimen? Further complicating matters was how best to introduce the concept of formula-feeding to HIV-infected mothers who may not have access to clean water and bottles and for whom not breastfeeding might be a stigma. The initial Horizons PMTCT studies (1999–2003) sought to answer these fundamental questions.

By the early 2000s, PMTCT pilot programs were in place in numerous countries as the global health community, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), governments, and international donors mobilized to fund and/or implement services. While programs generated service statistics on several indicators of uptake, there were little data about the quality of programs and the effectiveness of strategies to encourage service utilization and adherence to PMTCT recommendations. A second set of Horizons studies (2004–2007) sought to address gaps in adherence to ARV prophylaxis; examine roles of family planning in PMTCT programs; show the value of psychosocial support for HIV-positive mothers; and identify ways to improve the quality of care and follow-up for women in the postpartum period.

This article provides an assessment of the findings of Horizons research studies on PMTCT interventions from the late 1990s until 2007, and identifies needs for follow-on efforts.

STUDY DESIGNS AND METHODS

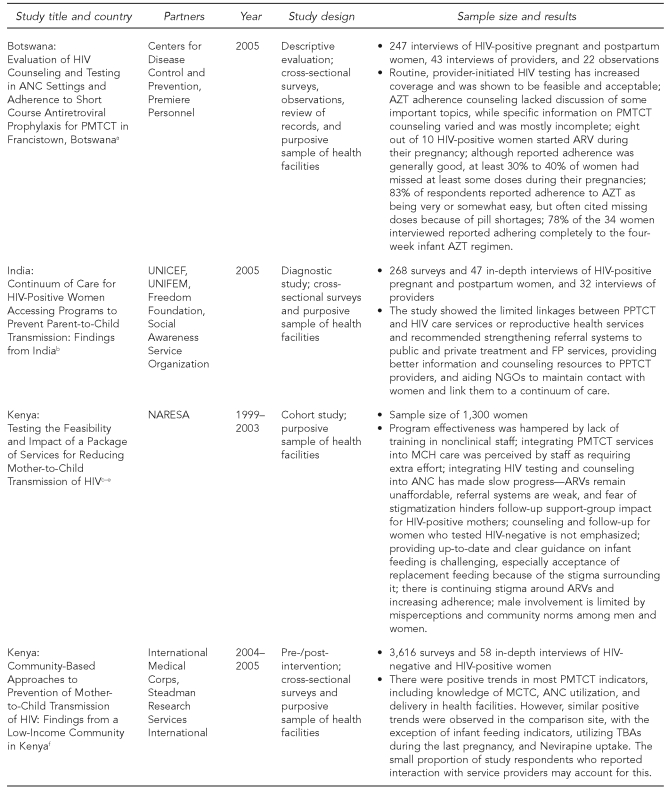

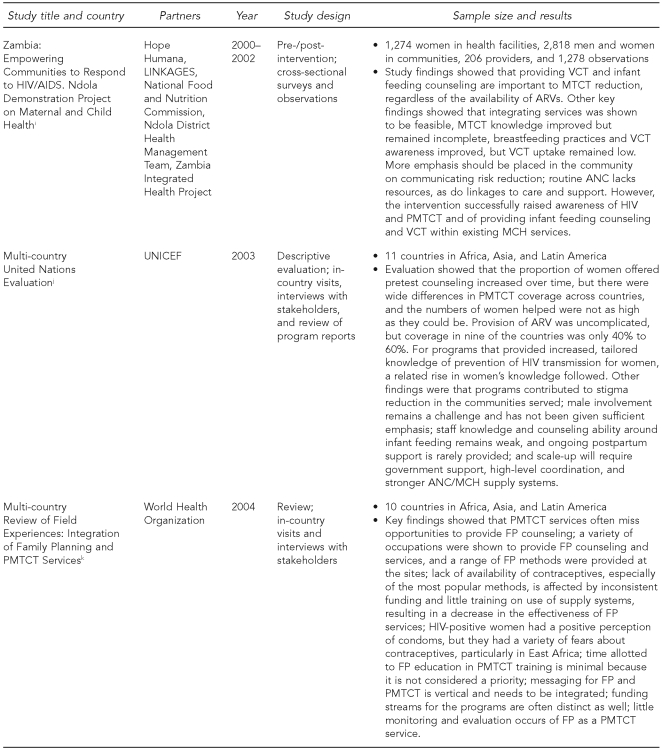

The Horizons PMTCT portfolio of studies utilized a variety of study designs (Figure 1). The first set of studies, begun in 1999, included cohort studies of women and infant pairs in Kenya and Zambia to determine feasibility, acceptability, and impact of implementing PMTCT programs outside of a controlled clinical setting. The second set included diagnostic and intervention studies and evaluations. Studies assessing existing services (in Botswana and India) and new service-delivery models (in Kenya, South Africa, Swaziland, and Zambia) included a variety of data collection activities such as interviews with pregnant and postpartum clients, interviews with health providers and managers, observations of client-provider interactions, and review of records. Most data collection activities took place at the health facilities; the assessment of infant adherence to ARV prophylaxis in Botswana also included home visits. The methodologies used were designed to be representative of women targeted by the PMTCT program in the geographic area where the studies were conducted. Careful considerations were taken to minimize participant risk, such as inadvertently revealing women's HIV status through their participation in the study, and strict guidelines of confidentiality were established. All studies were approved in each country as well as by the Population Council's Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the United States.

Figure 1.

Sample characteristics and study design among Horizons PMTCT studies, 1999–2007

aBaek C, Creek T, Jones L, Apicella L, Redner J, Rutenberg N. Evaluation of HIV counseling and testing in ANC settings and adherence to short course antiretroviral prophylaxis for PMTCT in Francistown, Botswana. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2009.

bMahendra VS, Mudoi R, Oinam A, Pakkela V, Sarna A, Panda S, et al. Continuum of care for HIV-positive women accessing programs to prevent parent-to-child transmission: findings from India. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

cRutenberg N, Baek C, Kankasa C, Nduati R, Mbori-Ngacha D, Siwale M, et al. Family planning and PMTCT services: examining interrelationships, strengthening linkages. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

dRutenberg N, Kankasa C, Nduati R, Mbori-Ngacha D, Siwale M, Geibel S, et al. HIV voluntary counseling and testing: an essential component in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

eRutenberg N, Kankasa C, Nduati R, Mbori-Ngacha D, Siwale M, Kalibala S, et al. Infant feeding and counseling within Kenyan and Zambian PMTCT services: how well does it promote good feeding practices? Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

fKaai S, Baek C, Geibel S, Omondi P, Ulo B, Muthumbi G, et al. Community-based approaches to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: findings from a low-income community in Kenya. Horizons Final Report. Nairobi: Population Council; 2007.

gBaek C, Mathambo V, Mkhize S, Friedman I, Apicella L, Rutenberg N. Key findings from an evaluation of the mothers2mothers program in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

hWarren C, Shongwe R, Waligo A, Mahdi M, Mazia G, Narayanan I. Repositioning postnatal care in a high HIV environment: Swaziland. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

iHope Humana, LINKAGES, National Food and Nutrition Commission, Ndola District Health Management Team, Horizons Program, Zambia Integrated Health Project. Empowering communities to respond to HIV/AIDS. Ndola demonstration project on maternal and child health: operations research final report. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

jRutenberg N, Baek C, Kalibala S, Rosen J. Evaluation of United Nations-supported pilot projects for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. New York: UNICEF and Population Council; 2003.

kRutenberg N, Baek C. Field experiences integrating family planning into programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Stud Fam Plann 2005;36:235-45.

PMTCT = prevention of mother-to-child transmission

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ANC = antenatal care

AZT = azidodeoxythymidine

ARV = antiretroviral

UNICEF = United Nations Children's Fund

UNIFEM = United Nations Development Fund for Women

PPTCT = prevention of parent-to-child transmission

FP = family planning

NGO = nongovernmental organization

NARESA = Network of AIDS Researchers in Eastern and Southern Africa

MCH = maternal and child health

MTCT = mother-to-child transmission

TBA = traditional birth attendant

BASICS = Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival (United States Agency for International Development)

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

VCT = voluntary counseling and testing

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

If you build it, will they come?

An evaluation of United Nations (UN)-supported pilot programs and cohort studies in Kenya and Zambia5 found that it was feasible and acceptable to implement within ANC what was then a new intervention. For instance, ANC providers incorporated into routine care the provision of HIV information, HIV counseling, the collection of blood for an HIV test, and informing and counseling women about ARV prophylaxis and alternative infant feeding methods. There was no evidence that the introduction of HIV services into ANC discouraged women's ANC utilization.

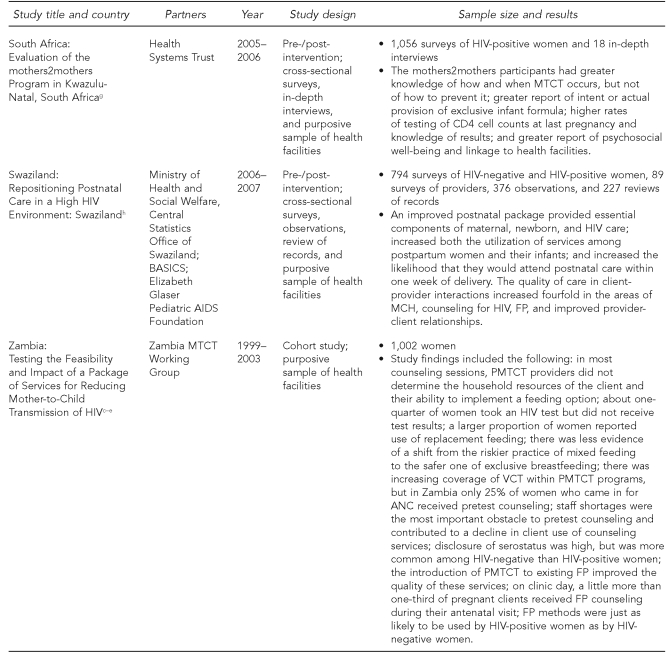

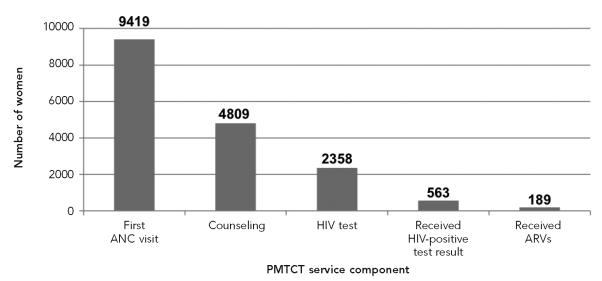

However, these new PMTCT services were delivered to only a minority of women accessing ANC. Among women who sought ANC, the lack of participation in or adherence to various PMTCT program recommendations from HIV counseling and testing, to returning for a positive result, to receipt and ingestion of ARV prophylaxis created a cascade of ever-diminishing service utilization (Figure 2). Reasons for the low uptake included women not wanting to know their HIV status, as no treatment support was available for HIV-infected women at that time; concern about stigma; and lack of male and community support. Additionally, delivery of these services was challenging, due to limited human resource capacity and insufficient supplies. As a consequence, in the three study sites in Kenya and Zambia, coverage of ARV prophylaxis was 15% or less among HIV-positive pregnant women.

Figure 2.

Cascade of service utilization, Chipata clinic, Zambia, 2003

ANC = antenatal care

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ARV = antiretroviral

PMTCT = prevention of mother-to-child transmission

For those who adhered to PMTCT recommendations, the nascent programs had the hoped-for outcomes. For example, among those who received ARV prophylaxis at the Lusaka, Zambia study site, infant infection rates assessed through polymerase chain reaction testing found that intra-partum transmission had been reduced by more than 50%. Thus, real-world use effectiveness matched clinical effectiveness.6

The issue of infant feeding in the UN evaluation as well as in the cohort studies was identified as particularly challenging. Policies at that time dictated presenting women with the pros and cons of feeding options (e.g., breastfeeding with early weaning or exclusive formula feeding),7 but observations in the Zambia cohort revealed that in more than a third of sessions, providers did not explain the feasibility and acceptability of various feeding options. More often than not, providers held the opinion that HIV-positive women should not breastfeed their infants. In discussions around infant feeding, less than a fifth of the sessions included inquiring if the woman had disclosed her status to a partner or family member, or whether adequate water and fuel were available for safe use of infant formula. In Kenya, self-reports of infant feeding practices at six weeks postpartum among women who were HIV-positive, HIV-negative, and of unknown HIV status indicated that most women were using a mixed feeding method, in marked contrast to the infant feeding recommendations.8

Improving utilization and impact

By the early 2000s, PMTCT pilot programs were in place, but they were reaching only a small proportion of HIV-positive pregnant women.5 Implementation of PMTCT services at their most basic included HIV counseling and testing to identify HIV-positive women during ANC, provision of ARV prophylaxis to HIV-positive women and their exposed infants, and infant feeding information. Most programs ended soon after the women delivered. Testing of strategies and information about how to strengthen programs to address barriers to service delivery and uptake, offer comprehensive PMTCT services, and effectively use resources for scale-up was needed. Horizons' second set of studies aimed to fill these gaps. Key results that emerged from this phase of operations research included the following:

Psychosocial support from peers helps women to adhere to PMTCT program recommendations.

Mothers2mothers (m2m) is a clinic-based peer support program that provides education and psychosocial support to HIV-positive pregnant women and new mothers, helps women access existing PMTCT services, and offers postpartum follow-up with mothers and infants. The Horizons program completed the first evaluation of m2m as it expanded services in the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa and documented that participating women were significantly more likely to report (1) disclosure of HIV status to at least one individual, (2) testing of CD4 cell counts during pregnancy, (3) Nevirapine receipt for mother and infant, and (4) an exclusive method of infant feeding. Furthermore, they were less likely to report feeling alone in the world, overwhelmed by problems, and hopeless about the future.9 These results suggest that the m2m model of peer support yielded substantial benefits and increased uptake of PMTCT services. The relevance of peer support extends beyond the region; in India, where peer psychosocial support was not offered at the study sites, HIV-positive women requested structured opportunities to meet and support one another.10

Training of staff on postnatal ward and use of peer educators improves infant feeding practices among women who recently delivered.

Because up to 50% of infant infections occur through breastfeeding, support of appropriate infant feeding practices is critical.11 Infant feeding remains a challenging component of PMTCT. Recent research shows that exclusive breastfeeding is as likely to lead to HIV-free survival as avoiding breastfeeding.7,12 The recommendation in place at the time of the Horizons studies was for HIV-positive women to breastfeed exclusively unless the use of formula was determined to be “acceptable, feasible, affordable, safe, and sustainable.” However, this recommendation was difficult to implement and operationalize in programs.13

Horizons studies indicate that although infant feeding continues to be challenging, intensive interventions can positively impact infant feeding practices. Recognizing the complexity and challenges of promoting infant feeding practices inconsistent with cultural norms of mixed breastfeeding and supplemental liquids and/or solids in sub-Saharan Africa, Horizons conducted a study from 2000 to 2002 in Zambia that focused on improving infant feeding among HIV-positive mothers and saw encouraging results.14 Key factors in this improvement involved conscientious reinforcement of breastfeeding promotion, community education and mobilization, and intensive training of clinic and community-based workers. In Swaziland, baseline data collection revealed incorrect information among providers, mothers, and families regarding appropriate feeding options for new mothers in the context of HIV. However, training of nurse-midwives, nurses, and nursing assistants who provided postnatal care produced significant improvements in infant feeding knowledge with concomitant increases in proper breastfeeding practices among new mothers prior to discharge from the hospital.15 The m2m evaluation in South Africa, where access to clean water was nearly universal, found that peer education and mentorship increased the likelihood of using an exclusive infant feeding method—in most instances, exclusive formula feeding—among women four to 12 weeks postpartum.9

Prioritizing other services and re-orienting providers is feasible and leads to desired comprehensive service.

A comprehensive approach to PMTCT includes linking women to family planning services to prevent unintended pregnancy for HIV-positive women.16 Data from a 2004 Horizons review of field experiences in 10 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America found that PMTCT sites miss opportunities to provide clients with family planning counseling. For example, in Kenya and Zambia, fewer than half of HIV-positive women received information about family planning at an antenatal or postpartum visit.17 Moreover, 2005 data from Kenya demonstrated that although most HIV-positive women did not plan to have additional children and intended to use family planning, only half of new mothers reported discussing these issues with their provider.18 In India, although more than 80% of the postpartum women interviewed did not want more children, less than half of them reported not using a family planning method. Although condoms are the most common family planning method used by HIV-positive women, only one-third reported receiving condoms from their PMTCT service provider following delivery.10

Despite deficiencies in consistent provision of family planning services to HIV-positive women, many of the necessary elements are in place: family planning services are generally available at PMTCT sites, PMTCT provider training includes family planning, and programs incorporate both family planning and PMTCT promotion messages. The Horizons review highlighted the opportunity to build on these elements and give greater priority to family planning as a PMTCT strategy in policies and program implementation, adapt family planning services to meet the needs of HIV-positive women, promote values clarification with providers about reproductive rights, and work toward better continuity between antenatal PMTCT and postpartum family planning services.

Linkage to care and treatment for HIV-positive women and their families is another cornerstone of comprehensive PMTCT programming, and Horizons studies identified needed improvements in systematic follow-up of women and linkages to care and treatment.16 In India, a diagnostic study examining the continuum of care for HIV-positive women found that only 41% of HIV-positive women interviewed were aware of ART, although these services were available, and just one in five women reported that their PMTCT provider informed them of this service. Among women on treatment, only one in 10 women reported being referred to ART services by a PMTCT provider.10 In a Horizons study in Botswana, a smaller proportion of pregnant women in comparison with postpartum women were on ART, suggesting the need to prioritize ARV eligibility and enrollment while women are pregnant.19

The difficulty with follow-up of mother-infant pairs reflects, in part, inherent weaknesses in the infrastructures of health systems. A Horizons intervention study conducted in Swaziland demonstrated the benefits of improved postnatal care that included an extra postpartum visit in the first week following delivery, a critical time in the care of new mothers and infants.15 After the introduction of the intervention, postpartum women were three times more likely to access postnatal care within one week of delivery, and HIV-positive women and their infants were significantly more likely to have initiated cotrimoxazole. Moreover, improved communication between providers and clients was observed, including provision of information to HIV-positive women on availability of additional services, such as family planning, food supplements, and support groups.15

Expanded coverage of HIV testing in ANC

Many Horizons studies were conducted during the time when the recommendation was changing from only offering HIV testing after individual pretest counseling to routinely offering HIV testing during ANC, now widely recommended.16,20–22 Horizons studies documented that the majority of pregnant women who had at least one ANC visit in the study sites also had undergone HIV testing. Moreover, continued implementation of routine testing at ANC sites with PMTCT programming can rapidly improve coverage. The proportion of postpartum women reporting that they took an HIV test at an ANC visit in Kenya increased from 84% to 93% between 2004 and 2005,8 and in Swaziland, this figure rose from 72% to 92% between 2006 and 2007.15 In India, nearly three-quarters of HIV-positive women interviewed underwent HIV testing as part of their ANC, suggesting that HIV testing during ANC is making a notable contribution toward HIV testing among women of reproductive age.10,23

High rates of disclosure by HIV-positive women

As testing among pregnant women has increased, so has disclosure by HIV-positive women, the majority of whom report disclosing their HIV status to at least one individual. Horizons studies found that more than three-quarters of HIV-positive women surveyed in the Botswana, India, South Africa, Kenya, and Swaziland studies8–10,15,18,19 reported disclosing their status to at least one individual, most commonly a partner or husband. This rate held constant despite wide differences in marriage rates in the study populations. Disclosure rates from these recent Horizons studies exceeded those reported from a 2004 synthesis of studies,24 which found disclosure rates were much lower for women tested during ANC compared with freestanding VCT sites. Possible reasons for this increase include greater HIV awareness, maturation of PMTCT programs, a shift to routinely offering HIV testing, and increased services for HIV care.

Supporting adherence to ARV prophylaxis

While programs often report the number of HIV-positive pregnant women beginning AZT and receiving Nevirapine for PMTCT, effectiveness of prophylactic treatment is dependent on the level of adherence by individuals to these regimens. Horizons examined the operational aspects affecting adherence in Botswana and found that most HIV-positive pregnant women received only one posttest counseling session, providing limited opportunity to explain and promote adherence. Half of the staff providing adherence counseling said they discussed the importance of taking the correct dose and taking it on schedule, but far fewer providers reported discussing other important topics, such as the purpose of medications and side effects. The majority of women remembered information on why AZT is needed, how to take AZT, and the importance of taking AZT on schedule; however, only 14% of participants recalled receiving written materials developed specifically for HIV-positive women.

About eight of 10 HIV-positive women who were tested and received their test results in the Botswana study reported starting ARV prophylaxis during their pregnancy, which was similar to what was reported in Horizons studies in India, Kenya, and South Africa. These self-reports for women's prophylactic receipt are consistent with service statistics from 13 country programs supported by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.25 The Botswana study provided some insights into how often and why women miss doses among those who are taking a complex regimen. Among HIV-positive pregnant women and HIV-positive women in the postnatal ward reporting taking AZT, nine out of 10 had taken the appropriate number of tablets the two days prior to the interview, but 30% to 40% of women missed at least some doses during their pregnancies. The majority of women reported that adherence to their AZT regimen was easy, although the requirement for resupply proved challenging for some; one of the main reasons for failing to take their medication was that they had run out of it.

The Botswana study results suggest several important program actions for promoting adherence to a complex regimen. These include standardizing posttest counseling content through the use of job aids, encouraging provision of at least two posttest counseling sessions for each woman, reducing the frequency of refills, and encouraging women to refill their supply before they run out of pills.

In addition to providing ART prophylaxis, it is imperative to determine the CD4 levels of HIV-positive pregnant women, enabling women with advanced disease to receive treatment for their own health and to access a more efficacious regimen to reduce vertical transmission.16 Findings from Botswana, South Africa, and Swaziland demonstrate that the majority of pregnant and recently postpartum HIV-positive women interviewed accessed CD4 testing; in South Africa and Swaziland, the programs that were evaluated specifically promoted CD4 testing as part of comprehensive care for HIV-positive women.

Research utilization

In addition to conducting operations research, Horizons has emphasized dissemination of data to facilitate research utilization, including research from our portfolio of PMTCT studies. For example, the cohort studies in Kenya and Zambia generated evidence that informed the scale-up of PMTCT in both countries. In Kenya, the study produced a training curriculum, educational materials, and an information system that were subsequently adopted by the National AIDS Control Program of Kenya for its nationwide PMTCT program. In South Africa, the Horizons evaluation of the m2m program was the first external evaluation of a well-known program, providing quantitative evidence of the benefits of peer psychosocial support. Based on the Horizons study results, the m2m program is being scaled up in several sub-Saharan African countries.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PRIORITIES FOR RESEARCH AND PROGRAMS

Since the inception of PMTCT programming in resource-constrained settings, Horizons has undertaken operations research studies to answer critical questions about how programs function in the real world and how better to serve women and infants in need. The first set of studies demonstrated the feasibility of PMTCT programs and documented various challenges. The research portfolio from the second set of Horizons studies assessed different approaches providing comprehensive services beyond the basic package of PMTCT services. An identified best practice is the inclusion of peer psychosocial support.

Programs should also strive to provide the most effective ARV prophylaxis regimen possible, as data from Botswana demonstrated that administration of a more complex regimen within ANC is both feasible and acceptable. The study also exposes operational areas that need attention when providing more complex ARV regimens as part of a PMTCT program. These include the importance of providing sufficient counseling to give essential information, client-oriented resupply systems, adherence support activities after the regimen is initiated, and maintaining ongoing contact with clients to monitor side effects or medication problems.

Infant feeding continues to be challenging, and there must be structured support in providing information to women not only while they are pregnant, but also after they have delivered and are feeding their infants. Horizons studies have documented successful approaches to doing this—peer support, reorienting postnatal care, and making infant feeding counseling an integral part of HIV counseling in the ANC setting—in South Africa, Swaziland, and Zambia. Finally, findings underscore the need to establish close ties with other services such as family planning and ART.

To provide a continuum of care from antenatal to postnatal PMTCT services and onto HIV care, interviewers with service providers and HIV-positive women in Botswana, India, South Africa, and Zambia suggest that PMTCT programs should strengthen their referral links among ANC, delivery, child health, and HIV services; better equip PMTCT providers to inform and counsel women about a continuum of care; and engage community groups and NGOs to maintain contact with women over time and link them and their families to a continuum of care.

A critical next step in operations research is to test programmatic strategies for supporting and tracking women and infants beyond the early postpartum period, creating a seamless continuum from PMTCT programs to the early identification of HIV-infected infants to provision of HIV care for the mother and infant as needed. Adequate follow-up would encourage safer forms of feeding, link women to family planning services, and test infants at multiple points in their lives. Postpartum follow-up would also permit the measurement of the impact of PMTCT programs. Until now, determination of transmission rates has been rare, as programs have relied on proxy measures of effectiveness. Testing of HIV-exposed infants at multiple points such as six weeks postpartum, six weeks post weaning, and 18 months of age would allow the estimation of intrapartum, early/postpartum, and late transmission rates and HIV-free survival. Such research could also answer operational questions regarding how to provide infant testing as a routine service in a programmatic setting, and how to link infants who are found to be HIV-positive with care.

Beyond tracing mother and infant pairs who participate in the program, it is necessary to measure the public health impact of the PMTCT programs by generating population-based data. As an example, this could involve surveillance at “under-5” clinics, which provide immunization and other well-baby services for children, and conducting surveys at households in the catchment areas of health facilities providing PMTCT services.

Hand-in-hand with an emphasis on preventing HIV infection in infants and serving as a critical entry point for HIV care for HIV-infected women and their children, efforts to promote primary prevention of HIV as a component of PMTCT cannot be ignored. Primary prevention among women of reproductive age is an important approach to PMTCT.16 Operations research can test new counseling protocols in ANC that give attention to women who test HIV-negative, particularly in high prevalence areas. Given some recent evidence suggesting increased vulnerability to acquisition of HIV during pregnancy,26 this is a necessary intervention to include in future PMTCT programs.

Finally, there is an urgent need to scale up the geographic coverage of PMTCT services. While uptake of HIV testing and ARV prophylaxis is high within individual sites that have PMTCT programming and among those who are already linked with the health facilities as indicated by these Horizons studies, there is a great need to expand services at a national level, as most countries have not successfully scaled up PMTCT services.1,2,16,27 Data from Horizons studies lend support to what is working well and what can be improved at the site level. Policy makers and program managers can use these data as they commit to making comprehensive PMTCT services available and as they move to serving women and infants in harder-to-reach areas and populations. A strong commitment toward both coverage and quality of services is required to serve the many women and infants in need.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the co-principal investigators and other individuals who contributed to the studies presented in this article. These studies were only made possible through much collaboration and enormous effort from numerous individuals. The authors extend specific thanks to Charlotte Warren, Vaishali Mahendra, and Ellen Weiss from the Horizons program for their contributions to these studies and review of this article, and to Scott Kellerman for his review of this article. Funding for these studies was made available by the United States Agency for International Development, the United Nations, and the World Health Organization. Finally, the authors express deep appreciation to the thousands of women in resource-constrained settings who agreed to participate in these studies.

Footnotes

These studies were made possible by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The contents of this article are the responsibility of the Population Council and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS epidemic update: November 2009. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler MG, Lampe MA, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP, Rogers MF. Reducing the risk of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission: past successes, current progress and challenges, and future directions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3) Suppl:S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stover J, Fahnestock M. Washington: Constella Futures, POLICY Project; 2006. Coverage of selected services for HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment in low- and middle-income countries in 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutenberg N, Baek C, Kalibala S, Rosen J. New York: UNICEF and Population Council; 2003. Evaluation of United Nations-supported pilot projects for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIVM. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kankasa C. Provision of VCT and ARVS: achievements and challenges. Presented at the Horizons PMTCT Symposium; 2003 Dec 10; Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2007. HIV and infant feeding: new evidence and programmatic experience: report of a technical consultation held on behalf of the Inter-agency Task Team (IATT) on prevention of HIV infections in pregnant women, mothers and their infants. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaai S, Baek C, Geibel S, Omondi P, Ulo B, Muthumbi G, et al. Horizons Final Report. Nairobi: Population Council; 2007. Community-based approaches to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: findings from a low-income community in Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baek C, Mathambo V, Mkhize S, Friedman I, Apicella L, Rutenberg N. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Key findings from an evaluation of the mothers2mothers program in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahendra VS, Mudoi R, Oinam A, Pakkela V, Sarna A, Panda S, et al. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Continuum of care for HIV-positive women accessing programs to prevent parent-to-child transmission: findings from India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler MG, Newell ML. Breastfeeding and HIV-1 transmission in resource-limited settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:230–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2001. New data on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and their policy implications: conclusions and recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherty T, Chopra M, Nkonki L, Jackson D, Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa: “When they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me.”. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:90–6. doi: 10.2471/blt.04.019448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hope Humana, LINKAGES, National Food and Nutrition Commission, Ndola District Health Management Team, Horizons Program, Zambia Integrated Health Project. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2003. Empowering communities to respond to HIV/AIDS. Ndola demonstration project on maternal and child health: operations research final report. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren C, Shongwe R, Waligo A, Mahdi M, Mazia G, Narayanan I. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Repositioning postnatal care in a high HIV environment: Swaziland. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2007. Guidance on global scale-up of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: towards universal access for women, infants and young children and eliminating HIV and AIDS among children. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutenberg N, Baek C. Field experiences integrating family planning into programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36:235–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baek C, Kaai S, Geibel S, McOdida P, Ulo B, Rutenberg N. Assessing HIV-positive women's fertility desires and demand for family planning in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programs in Nairobi, Kenya. Presented at the American Public Health Association 133rd Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2005 Dec 10–14; Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baek C, Creek T, Jones L, Apicella L, Redner J, Rutenberg N. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2009. Evaluation of HIV counseling and testing in ANC settings and adherence to short course antiretroviral prophylaxis for PMTCT in Francistown, Botswana. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2003. The right to know: new approaches to HIV testing and counselling. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization; Global Reference Group on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights. Geneva: UNAIDS and WHO; 2004. UNAIDS/WHO policy statement on HIV testing. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolu OO, Allread V, Creek T, Stringer E, Forna F, Bulterys M, et al. Approaches for scaling up human immunodeficiency virus testing and counseling in prevention of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission settings in resource-limited countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3 Suppl):S83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, United States Agency for International Development, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, the Policy Project. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Coverage of selected services for HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support in low and middle income countries in 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sripipatana T, Spensley A, Miller A, McIntyre J, Sangiwa G, Sawe F, et al. Site-specific interventions to improve prevention of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus programs in less developed settings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3 Suppl):S107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RH, Li X, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Brahmbhatt H, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Increased risk of incident HIV during pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366:1182–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Druce N, Nolan A. Seizing the big missed opportunity: linking HIV and maternity care services in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]