SYNOPSIS

While male-to-male sexual behavior has been recognized as a primary risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), research targeting men who have sex with men (MSM) in less-developed countries has been limited due to high levels of stigma and discrimination. In response, the Population Council’s Horizons Program began implementing research activities in Africa and South America beginning in 2001, with the objectives of gathering information on MSM sexual risk behaviors, evaluating HIV-prevention programs, and informing HIV policy makers. The results of this nearly decade-long program are presented in this article as a summary of the Horizons MSM studies in Africa (Senegal and Kenya) and Latin America (Brazil and Paraguay), and include research methodologies, study findings, and interventions evaluated. We also discuss future directions and approaches for HIV research among MSM in developing countries.

From the beginning of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, male-to-male sexual behavior has been recognized as a primary risk factor for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Since that time, most HIV-related behavioral research among men who have sex with men (MSM) has been conducted in North America and Europe,1 and now HIV-prevention counseling and testing are cornerstones for HIV programs serving MSM populations in the developed world. Research from Latin America2 included assessments and evaluations of MSM and their HIV risk from Mexico,3,4 Brazil,5–7 and the Dominican Republic.8 In Asia, recognition of the increased risk of HIV among MSM was built upon a limited number of assessments in Thailand,9 Cambodia,10 and China.11

In Africa, however, there has been a profound absence of any policy, program, or research initiative that assessed MSM as a vulnerable population or even considered MSM as a distinct subpopulation. Since the first appearance of HIV on the continent, most African HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) policies were based on the belief that unprotected heterosexual contact was the primary driver of the African epidemic.12–14 This was a key factor in convincing African policy makers of the severity of the epidemic, and since that time, nearly all HIV-prevention programs in Africa have focused exclusively on the risks associated with vaginal intercourse. South Africa was one exception, where its post-apartheid constitution provided legal protection to homosexuals and empowered some grassroots HIV-prevention initiatives, albeit mainly by organizations operating in urban settings that did not widely target predominantly black townships.

Prior to 2000, research on MSM in Africa was limited to occasional ethnographic or qualitative studies,15–17 but no population-based surveys or assessments attempted to quantify and characterize MSM as a subpopulation within African social structures, let alone assess or survey sexual behaviors and exposure to STIs. In the late 1990s, African heads of states Daniel arap Moi of Kenya and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe both publicly denied that indigenous homosexuality or same-sex sexual behavior existed in Africa without coercion through Western or foreign influence.18 Such prominent public statements reflect a deeply entrenched culture of homophobia that persists today. Recent opinion articles in African newspapers state that same-sex sexualities “have been non-African since time immemorial,”19 and “violate the cultural, religious, moral, and legal norms of the country.”20

The denial of MSM behavior, and the stigma associated with it, discouraged African researchers from objectively evaluating homosexuality for fear that others would ridicule them and question their sexual orientation.21 However, limited qualitative documentation as well as an abundance of anecdotal evidence suggested that MSM are present in Africa and likely are at increased risk for HIV, but are largely invisible from researchers and policy makers. Given this discrepancy, the Horizons program expanded its portfolio to investigate the vulnerability of MSM in Africa, first through descriptive assessments, and then followed by intervention studies in both Senegal and Kenya.

In contrast to Africa, the MSM populations in Central and South America have experienced different challenges. While targeted homophobia and discrimination is still an essential problem in the region, the near institutional denial seen in Africa does not exist in the same form. The distinction is important as it affected the strategy for developing a research portfolio on either continent. In Africa, Horizons determined that it was most important to implement studies to describe and characterize the population as a way to convince policy makers that MSM did indeed exist. However, in South America, the Horizons program was able to focus on analysis of MSM behaviors to develop new evidence-based approaches to risk reduction and to guide prevention programs. The results of this nearly decade-long program are presented in this article as a summary of the Horizons MSM studies in Africa and Latin America, including research methodologies, study findings, and programs evaluated. We also discuss future directions and approaches for HIV research on MSM in developing countries.

RESEARCH STRATEGIES

Horizons and partners designed, conducted, and published the first large-scale descriptive studies of African MSM in 2001 in Dakar, Senegal,22 and 2004 in Nairobi, Kenya.23 Both studies utilized quantitative and qualitative survey methods including in-depth interviews and ethnographic observations. These studies documented the existence of MSM populations within major African cities, previously unknown to national AIDS programs, as well as risk behaviors that rendered these populations especially vulnerable to HIV. Following the success of these initial assessments, Horizons and regional partners expanded the research agenda to include an intervention study of MSM in Senegal24 and of male sex workers who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya.25 The latter activity also utilized capture-recapture methods to enumerate the number of active male sex workers, estimated at more than 700 in Mombasa alone.26

In the South American studies, Horizons and its partners incorporated recent innovations in probability sampling for MSM, as well as HIV testing of the study population to produce seroprevalence estimates. The Brazilian study was conducted in the southeastern city of Campinas.27 In Paraguay, MSM were enrolled for a study in Ciudad del Este, on the border of Brazil and Argentina, with a large concentration of high-risk populations such as truck drivers, drug users, and sex workers (male and female).28

Recruiting hidden MSM with snowball, respondent-driven, and time-location sampling

Entrenched homophobia makes identifying MSM a particularly challenging task. The Horizons studies utilized three different sampling strategies designed to recruit members of hard-to-reach populations (e.g., drug users or sex workers). Snowball sampling, in which participants randomly recruit peers from their personal networks, was used to reach MSM in the Dakar and Nairobi studies. Snowball sampling, however, is a nonprobability sampling method, which may fail to reach some MSM and produce biased results.29 The two Latin American studies used respondent-driven sampling (RDS), a more rigorous methodology similar to snowball sampling that utilizes more controlled peer recruitment and statistical weights to provide theoretically unbiased population estimates.30–33 RDS has been successful in recruiting MSM in previous studies in other countries,34–36 including Uganda37 and Zanzibar38 in Africa, thus establishing the method as feasible and methodologically preferable to snowball sampling. Despite the advantages of RDS, recruitment of MSM proved challenging in the Latin American studies, though this appeared to be related to fears of disclosure and testing for HIV rather than to the methodology itself. Nevertheless, these studies are the first to provide population estimates for HIV prevalence and associated risk behaviors among MSM in Brazil and Paraguay, and led to the adoption of RDS for the national surveillance of high-risk populations in Brazil.

Time-location sampling, in which participants are sampled from a list of contact locations and the times in which they are found at these venues, was used to sample male sex workers in Mombasa. First, Horizons and partners successfully implemented a capture-recapture enumeration of male sex workers who sell sex to men.26 This entailed conducting two enumerations of male sex workers one week apart, whereupon men counted in only one week or both weeks (“recaptures” or matches) enabled a population estimation derived from capture-recapture calculation. This activity also produced detailed data on locations and times where male sex workers were seeking clients. These data were utilized to produce the time-location sampling frame. Research staff avoided public scrutiny by training MSM as “mobilizers” to identify male sex workers at these locations and escort them to a central location for interviewing. These methodologies were effective in Mombasa, but further study is needed to compare the generalizability and reliability of time-location sampling vs. RDS among male sex worker populations.

Qualitative data and local partnerships as critical elements

The African studies benefited from partnerships with anthropologists from respected local collaborating institutions in Senegal (Cheikh Anta Diop University) and Kenya (University of Nairobi), who supplemented the quantitative behavioral surveys with in-depth interviews and ethnographic observations. Qualitative interviews with MSM revealed that the majority of their male sexual partners were local (i.e., from the same communities) and that first sexual experiences with men often took place during adolescence with friends or acquaintances. Such results refuted prevailing beliefs in Africa that homosexual behavior was the result of foreign coercion. These partnerships proved critical in establishing the legitimacy of the research in Africa and provided a foundation for future partnerships with government agencies in both countries.

HIV AND STI RISK AMONG MSM

Sexual risk behaviors and networks

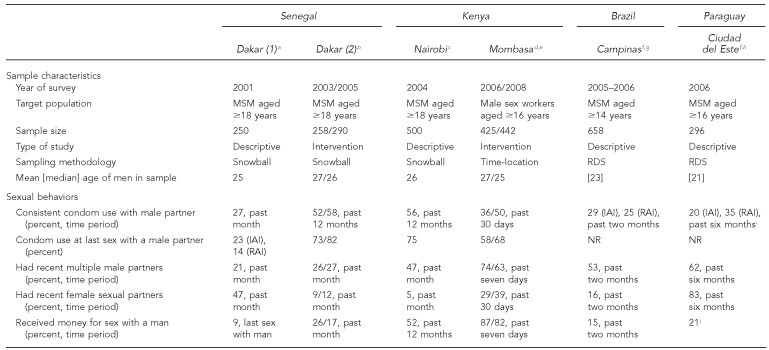

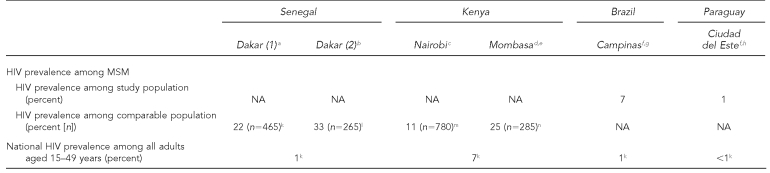

While the experience and realities of MSM in Africa and South America were different, results highlighted HIV vulnerabilities across all the Horizons studies. The Table summarizes the population characteristics and reported sexual behaviors of the six MSM studies described in this article. In the African studies, high levels of insertive and receptive anal sex with inconsistent condom use were the norm. In addition, high proportions of multiple or concurrent sex partners were reported in all studies, but were particularly high among Mombasa male sex workers and MSM in Nairobi, Campinas, and Ciudad del Este.

Reported condom use varied widely across studies. The 2001 assessment of MSM in Dakar found low levels of condom use with last male insertive partners (23%) and receptive partners (14%). Follow-up surveys in Dakar in 2003 and 2005, and in Nairobi in 2004, documented condom use at last sex at more than 70%. Consistent condom use (considered a more important indicator in terms of HIV risk reduction39,40) was reported by more than 50% of respondents in these surveys, but by only 36% of male sex workers in the 2006 Mombasa survey and less than 30% in Campinas and Ciudad del Este.

The prevalence of men selling sex to other men was surprisingly high in all areas studied. In addition to the Mombasa survey that specifically targeted male sex workers, the 2001 Dakar study documented that 9% of respondents reported selling sex to their last male partner; 15% of MSM in Campinas reported selling sex to men in the past two months; 21% of MSM in Ciudad del Este reported currently selling sex (primarily to male clients); and more than half of Nairobi MSM reported selling sex to men for money or gifts in the past year. While surprisingly high, these numbers may be a product of peer recruitment survey methods failing to reach more hidden or isolated segments of the MSM population—an area meriting further study.

These studies also demonstrate that heterosexual sex is common among MSM: 29% (2006) and 39% (2008) of male sex workers in the Mombasa surveys reported having a female paying or nonpaying sex partner in the past 30 days; 83% of MSM in Ciudad del Este had a female sex partner in the past six months; 88% of respondents in Senegal reported ever having sex with a woman; 5% of MSM in Nairobi reported having a female sex partner in the month prior to the survey; and 16% of MSM in Campinas reported having a female sex partner in the two months prior to the survey. These results underscore that MSM are not sexually isolated, and that potential “bridging” of homosexual and heterosexual practices by these men has broader public health implications.

HIV prevalence among MSM

HIV testing in the Ciudad del Este and Campinas populations revealed that prevalence was marginally higher than general population rates in the former, but much higher in the latter (Table). In addition, more than 70% of those testing positive were unaware of their status, suggesting the need to emphasize HIV testing in this group. HIV-prevention programs for younger MSM are particularly important—the Campinas study reported an HIV seroprevalence of 4% among MSM aged 14 to 19 years, a particularly alarming finding given that the national prevalence is less than 1%, and the mean age of sexual debut was 13.

Table.

Sample characteristics, sexual behaviors, and HIV prevalence of study or comparable populations, Horizons studies of MSM in developing countries, 2001–2008

aNiang CI, Tapsoba P, Weiss E, Diagne M, Niang Y, Moreau AM, et al. “It's raining stones”: stigma, violence and HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men in Dakar, Senegal. Cult Health Sex 2003;5:499-512.

bMoreau A, Tapsoba P, Ly A, Niang CI, Diop AK. Implementing STI/HIV prevention and care interventions for men who have sex with men in Senegal. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

cOnyango-Ouma W, Birungi H, Geibel S. Understanding the HIV/STI risks and prevention needs of men who have sex with men in Nairobi, Kenya. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2005.

dGeibel S, Luchters S, King'ola N, Esu-Williams E, Rinyiru A, Tun W. Factors associated with self-reported unprotected anal sex among male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:746-52.

eGeibel S, Kingola N, Luchters S. Impact of male sex worker peer education on condom use in Mombasa, Kenya. Presented at the 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and Prevention; 2009 Jul 21; Cape Town, South Africa [abstract TUAD204].

fRDS population estimates are presented for Brazil and Paraguay.

gde Mello M, de Araujo Pinho A, Chinaglia M, Tun W, Júnior AB, Ilário MCFJ, et al. Assessment of risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the metropolitan area of Campinas City, Brazil, using respondent-driven sampling. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

hChinaglia M, Tun W, de Mello M, Insfran M, Díaz J. Assessment of risk factors for HIV infection in female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

iConsistent condom use is reported for IAI and RAI with occasional male partners, defined as partners with whom the respondent had sex only once or from time to time and with whom he did not exchange money, drugs, or gifts for sex.

jMSM were asked whether they “currently” engage in sex work (i.e., receiving money, drugs, or gifts in exchange for anal or oral sex). The majority indicated they sold sex to male partners.

kUNAIDS. 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. Also available from: URL: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp [cited 2008 Oct 14].

lWade AS, Kane CT, Diallo PA, Diop AK, Gueye K, Mboup S, et al. HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS 2005;19:2133-40.

mAngala P, Parkinson A, Kilonzo N, Natecho A, Taegtmeyer M. Men who have sex with men (MSM) as presented in VCT data in Kenya. 16th International AIDS Conference; 2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto [abstract MOPE0581].

nSanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, van der Elst EM, Muhaari A, Davies A, et al. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS 2007;21:2513–20.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

MSM = men who have sex with men

RDS = respondent-driven sampling

IAI = insertive anal intercourse

RAI = receptive anal intercourse

NR = not reported

NA = not applicable

Disparities are even more alarming in African seroprevalence studies. Data from other non-Horizons studies and the Senegal intervention program revealed very high HIV prevalence compared with the general populations. In Senegal, where the national prevalence is 1%,41 HIV prevalence among MSM ranges from 22%42 among a national snowball sample to 33% among MSM who requested testing from intervention services during the second Dakar study.24 In Kenya, with a national prevalence of 7%,41 MSM prevalence ranges from 11% among MSM tested in voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) clinics43 to 25% among a convenience sample of 285 MSM enrolled in a vaccine trial cohort near Mombasa.44

Stigma, discrimination, and violence: barriers to counseling and treatment

Horizons documented a high level of physical, verbal, and sexual victimization of MSM. In Nairobi, male sex workers were significantly more likely to experience physical, sexual, and verbal abuse than other MSM, and were unlikely to report such abuse to the authorities. In Campinas, more than 30% of MSM reported physical abuse in their lifetime, but only 6% reported these incidents and only 11% sought medical treatment. Additionally, 78% reported psychological abuse, which was found to be independently associated with unprotected receptive anal intercourse (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.89; p<0.05).

Fear of public exposure prompted MSM to identify confidentiality as the most important consideration when seeking STI treatment or HIV counseling. At the same time, qualitative data revealed that MSM feared revealing their sexual identity and behaviors to health-care providers. In addition, in-depth interviews with health-care providers in Nairobi showed that counselors and providers generally did not ask about same-sex sexual behavior, and thus did not offer appropriate HIV-prevention messages.

Use of oil-based lubricants with condoms

All of the Horizons MSM studies in Africa documented high usage of petroleum jelly, baby oils, and lotions for lubrication during anal intercourse both with and without condoms. While a majority of respondents in the Senegal study reported using products such as Vaseline®, shea butter, body lotion, and shaving gels or creams, only 26% of MSM in Nairobi and 21% of male sex workers in Mombasa correctly knew that only water-based lubricants should be used with latex condoms, and only 15% of male sex workers in the 2006 survey had used a water-based lubricant with their last male client. In both Kenyan studies, reported use of oil-based lubricants was significantly associated with ever experiencing condom breakage, consistent with studies documenting decreased structural integrity of condoms when used with lubricants or preparations containing mineral or vegetable oils.45–47 Finally, respondents consider condoms to be available and affordable, while water-based lubricants are scarce and costly. In Nairobi and Mombasa, for example, water-based lubricants are only available in select supermarkets and pharmacies, where a 50-gram tube of K-Y® Jelly costs approximately U.S. $4.00 compared with U.S. $0.30 for a 25-gram container of petroleum jelly. Lubricant use was also low in Ciudad del Este, with only 28% using lubricants during insertive anal intercourse and 16% during receptive anal intercourse. Among lubricant users, only half reported using water-based lubricants.

INTERVENTION APPROACHES

Findings from initial studies suggested increasing outreach via peer educators and training service providers and counselors on, or sensitizing them to, the specific medical and prevention needs of MSM. In Dakar, strong collaborating partners trained 40 MSM peer educators and recruited 12 service providers to provide MSM-sensitive services with subsequent increases in HIV testing and consistent condom use among MSM.24

In Mombasa, 40 male sex worker peer educators were trained in HIV prevention and basic counseling skills. Additionally, 20 health-care providers from Mombasa-area hospitals and clinics were trained and sensitized to MSM issues including diagnosis of STIs and HIV counseling. Condoms and water-based lubricants were distributed via a drop-in center and by peer educators, with substantial uptake of both education sessions and drop-in center visits. Significant increases were recorded in correct knowledge of anal HIV transmission (65% to 73%, p<0.01), correct knowledge of use of water-based lubrications with latex condoms (21% to 41%, p<0.001), reported condom use with last male client (58% to 68%, p<0.01), and consistent condom use with male clients in the past 30 days (36% to 50%, p<0.001). Male sex workers reporting increased exposure (range: 0 to 5 + yearly contacts) to peer educators in the Mombasa area were more likely to report consistent condom use (AOR = 1.14, p<0.01).48

By ensuring discretion, these approaches were successful in providing HIV-prevention resources to MSM in highly stigmatized societies. In addition, other intervention models, including modified HIV counseling and testing for MSM, are being delivered by Liverpool VCT in Nairobi. These pilot projects, however, remain model programs and have yet to be adopted more broadly throughout Africa.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND NEXT STEPS

The Horizons studies have brought attention to an ignored, vulnerable population—indeed showing that MSM actually exist in some countries and are not a foreign phenomenon, but an African reality. The studies have added to the general knowledge of the HIV risks of MSM in developing countries, implemented innovative quantitative and qualitative sampling methodologies, and produced the first large-scale assessments of MSM in Africa. The Population Council, which directs the Horizons program, has been credited as “the first international [nongovernmental organization] to recognize that the HIV-related vulnerabilities of men who have sex with men in Africa deserved serious attention.”49

Currently, MSM research in Africa has expanded beyond the Horizons program. Published seroprevalence studies exist for Senegal,42 Kenya,44 Malawi,50 Namibia,50 Botswana,50 and South Africa,51,52 and other behavioral studies have been conducted for Uganda,37 South Africa,53,54 and Cameroon.55 This growing collection of research activities will bring necessary attention to the HIV vulnerabilities of MSM in sub-Saharan Africa.

At the policy level, while Brazil has included MSM as a priority group in its national HIV-prevention campaigns, most national HIV programs in Africa have been slow to acknowledge and address MSM in official policy. Only a few African countries mention MSM in their national strategic plans in the context of most-at-risk populations, and few or none have a specific national HIV policy for MSM. Many service providers are reluctant to officially provide services to MSM until these policy issues are addressed, and many researchers continue to avoid study of MSM for fear of stigma. In addition, community and religious stigma remains a barrier to implementation of service delivery and research initiatives, although some countries have seen increased public debate and discussion of the issue. Even simple measures, such as consistent provision of water-based lubricants, have yet to be adopted in many countries, although further study on the epidemiologic impact of lubrication use and condom breakage is needed.

MSM in developing countries continue to be both “understudied and underserved,”56 but we feel the best way to influence policy is through the provision of unbiased data. The work outlined in this article has already resulted in some movement: the directors of the National AIDS Commission in Senegal57 and National AIDS Control Council in Kenya58 have since acknowledged the existence of MSM and the need to address them in national HIV policy. In addition, the Population Council and Kenya's National AIDS Control Council hosted a regional conference on MSM for Eastern and Central African policy makers, including directors of national AIDS programs, in 2008.59 By gathering and informing those most influential in terms of designing policy and presenting the state of the science, we hope to have a broad and lasting effect on the provision of HIV-prevention services to this population. We also urge other organizations to expand their efforts toward understanding and addressing the HIV risks of MSM in developing countries.

Footnotes

The Horizons studies on men who have sex with men presented in this article were conducted in partnership or collaboration with several institutions and individuals, and would not have been successful without their substantial effort and contributions. The authors extend special thanks to the co-primary investigators for these studies and their affiliated partner institutions: Cheikh Niang, Institut des Sciences de L'Environnement, faculté des Sciences, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Senegal; Amadou Moreau, Population Council, Senegal; W. Onyango-Ouma, Institute of African Studies, University of Nairobi, Kenya; Harriet Birungi, Frontiers Program, Population Council, Kenya; Stanley Luchters, International Centre for Reproductive Health, Kenya; Juan Diaz, Maeve Brito de Mello, Adriana de Araujo Pinho, and Magda Chinaglia, Population Council, Brazil; Aristides Barbosa, Jr., National Program of STD/AIDS, Ministry of Health, Brazil; Suzanne Westman, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Brazil; Francisco Hideo Aoki, State University of Campinas, Brazil; and Magdalena Insfran de Martinzez, Regional AIDS Program of Alto Parana, Paraguay. The authors also thank other current and former staff and partner organizations of the Horizons program for their significant contributions to these studies over the years, including Naomi Rutenberg of the Population Council; Ellen Weiss of the International Center for Research on Women and formerly with the Population Council; Julie Pulerwitz of the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health; and Chris Castle, formerly with the International HIV/AIDS Alliance.

These studies were made possible by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The contents of this article are the responsibility of the Population Council and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stall RD, Hays RB, Waldo CR, Ekstrand M, McFarland W. The gay '90s: a review of research in the 1990s on sexual behavior and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 3):S101–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caceres CF. HIV among gay and other men who have sex with men in Latin America and the Caribbean: a hidden epidemic? AIDS. 2002;16(Suppl 3):S23–33. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200212003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramirez J, Suarez E, de la Rosa G, Castro MA, Zimmerman MA. AIDS knowledge and sexual behavior among Mexican gay and bisexual men. AIDS Educ Prev. 1994;6:163–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Suarez E, de la Rosa G, Castro MA. An HIV/AIDS prevention project for Mexican homosexual men: an empowerment approach. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:177–90. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr-Pontes LR, Gondim R, Mota RS, Martins TA, Wypij D. Self-reported sexual behaviour and HIV risk taking among men who have sex with men in Fortaleza, Brazil. AIDS. 1999;13:709–17. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904160-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison LH, do Lago RF, Friedman RK, Rodrigues J, Santos EM, de Melo MF, et al. Incident HIV infection in a high-risk, homosexual, male cohort in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:408–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro M, de Figueiredo Antunes CM, Greco M, Oliveira E, Andrade J, Lignani L, et al. Design, implementation, and evaluation at entry of a prospective cohort study of homosexual and bisexual HIV-1-negative men in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: Project Horizonte. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:182–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabet SR, de Moya EA, Holmes KK, Krone MR, de Quinones MR, de Lister MB, et al. Sexual behaviors and risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 1996;10:201–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyrer C, Eiumtrakul S, Celentano DD, Nelson KE, Ruckphaopunt S, Khamboonruang C. Same-sex behavior, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV risks among young northern Thai men. AIDS. 1995;9:171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girault P, Saidel T, Ngak S, de Lind Van Wijngaarden JW, Dallabetta G, Stuer F, et al. Sexual behavior, STIs and HIV among men who have sex with men in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2000. [cited 2007 Nov 27]. Available from: URL: http://www.fhi.org/en/HIVAIDS/pub/survreports/MSMCambodia/index.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhang B, Liu D, Li X, Hu T. A survey of men who have sex with men: mainland China. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1949–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melbye M, Njelesani EK, Bayley A, Mukelabai K, Manuwele JK, Bowa FJ, et al. Evidence for heterosexual transmission and clinical manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection and related conditions in Lusaka, Zambia. Lancet. 1986;2:1113–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90527-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronald AR, Ndinya-Achola JO, Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ngugi EN, et al. A review of HIV-1 in Africa. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1988;64:480–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter DJ. AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: the epidemiology of heterosexual transmission and the prospects for prevention. Epidemiology. 1993;4:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teunis N. Homosexuality in Dakar: is the bed the heart of a sexual subculture? J Gay Lesb Bisex Ident. 1996;1:153–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna N. On the margins: men who have sex with men and HIV in the developing world. London: Panos Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roscoe W, Murray SO, editors. Boy-wives and female husbands: studies in African homosexualities. New York: PALGRAVE; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelke M. “We wondered what human rights he was talking about”: human rights, homosexuality and the Zimbabwe International Book Fair. Crit Anthropol. 1999;19:289–314. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyamu HJ. Gays have no business fighting for recognition in Kenya. Daily Nation (Nairobi) 2007. Sep 28, Sect. 1:11 (col. 1)

- 20.Nkangi M. Govt must tighten screws on gays, lesbians. Daily Monitor (Kampala) 2007. Nov 28, Sect. 1:12 (col. 1)

- 21.Tapsoba P, Moreau A, Niang Y, Niang C. What kept away African professionals from studying MSM and addressing their needs in Africa? Challenges and obstacles; 15th International AIDS Conference; 2004 Jul 11–15; Bangkok, Thailand. abstract WePeC6155. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niang CI, Tapsoba P, Weiss E, Diagne M, Niang Y, Moreau AM, et al. “It's raining stones”: stigma, violence and HIV vulnerability among men who have sex with men in Dakar, Senegal. Cult Health Sex. 2003;5:499–512. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onyango-Ouma W, Birungi H, Geibel S. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2005. Understanding the HIV/STI risks and prevention needs of men who have sex with men in Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau A, Tapsoba P, Ly A, Niang CI, Diop AK. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Implementing STI/HIV prevention and care interventions for men who have sex with men in Senegal. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geibel S, Luchters S, King'ola N, Esu-Williams E, Rinyiru A, Tun W. Factors associated with self-reported unprotected anal sex among male sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:746–52. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318170589d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geibel S, van der Elst EM, King'ola N, Luchters S, Davies A, Getambu EM, et al. “Are you on the market?”: a capture-recapture enumeration of men who sell sex to men in and around Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2007;21:1349–54. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328017f843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Mello M, de Araujo Pinho A, Chinaglia M, Tun W, Júnior AB, Ilário MCFJ, et al. Assessment of risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the metropolitan area of Campinas City, Brazil, using respondent-driven sampling. Washington: Population Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinaglia M, Tun W, de Mello M, Insfran M, Díaz J. Assessment of risk factors for HIV infection in female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. Washington: Population Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 2):S67–72. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000172879.20628.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, Sabin K, Saidel T. Implementation and analysis of respondent driven sampling: lessons learned from the field. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salganik MJ. Variance estimation, design effects, and sample size calculations for respondent-driven sampling. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i98–112. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez-Valles J, Heckathorn DD, Váazquez R, Diaz RM, Campbell RT. From networks to populations: the development and application of respondent-driven sampling among IDUs and Latino gay men. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:387–402. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, Bramson H, Nemeth C, Sabin K, et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: findings from a pilot study. J Urban Health. 2006;83:459–76. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeka W, Maibani-Michie G, Prybylski D, Colby D. Application of respondent driven sampling to collect baseline data on FSWs and MSM for HIV risk reduction interventions in two urban centres in Papua New Guinea. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i60–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9103-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kajubi P, Kamya MR, Raymond HF, Chen S, Rutherford GW, Mandel JS, et al. Gay and bisexual men in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:492–504. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston L, Dahoma M, Holman A, Sabin K, Othman A, Martin R, et al. HIV infection and risk factors among men who have sex with men in Zanzibar (Ugunja), Tanzania; 17th International AIDS Conference; 2008 Aug 3–8; Mexico City. abstract WEPE0742. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1303–12. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis KR, Weller SC. The effectiveness of condoms in preventing heterosexual HIV transmission. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:272–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.UNAIDS. 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. [cited 2008 Oct 14]. Also available from: URL: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade AS, Kane CT, Diallo PA, Diop AK, Gueye K, Mboup S, et al. HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Senegal. AIDS. 2005;19:2133–40. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194128.97640.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angala P, Parkinson A, Kilonzo N, Natecho A, Taegtmeyer M. Men who have sex with men (MSM) as presented in VCT data in Kenya; 16th International AIDS Conference; 2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto. abstract MOPE0581. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, van der Elst EM, Muhaari A, Davies A, et al. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2007;21:2513–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2704a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voeller B, Coulson AH, Bernstein GS, Nakamura RM. Mineral oil lubricants cause rapid deterioration of latex condoms. Contraception. 1989;39:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(89)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen AD, Rosen T. Study of condom integrity after brief exposure to over-the-counter vaginal preparations. South Med J. 1999;92:305–7. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steiner M, Piedrahita C, Glover L, Joanis C, Spruyt A, Foldesy R. The impact of lubricants on latex condoms during vaginal intercourse. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:29–36. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geibel S, Kingola N, Luchters S. Impact of male sex worker peer education on condom use in Mombasa, Kenya; Presented at the 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and Prevention; 2009 Jul 21; Cape Town, South Africa. abstract TUAD204. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson CA. Off the map: how HIV/AIDS programming is failing same-sex practicing people in Africa. New York: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baral S, Trapence G, Motimedi F, Umar E, Iipinge S, Dausab F, et al. HIV prevalence, risks for HIV infection, and human rights among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sandfort T, Nel J, Rich E, Reddy V, Yi H. Race-related differences in rates of HIV testing and infection in South African MSM; Presented at the 17th International AIDS Conference; 2008 Aug 3–8; Mexico City. abstract TUPE0729. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men's Study. AIDS Behav. 2009 Aug 7; doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lane T, Shade SB, McIntyre J, Morin SF. Alcohol and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men in South African township communities. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(Suppl 4):S78–85. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandfort TG, Nel J, Rich E, Reddy V, Yi H. HIV testing and self-reported HIV status in South African men who have sex with men: results from a community-based survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:425–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henry E, Marcellin F, Yomb Y, Fugon L, Nemande S, Gueboguo C, et al. Factors associated with unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Douala, Cameroun. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Aug 24; doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036939. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ndoye I. L'expérience sénégalaise: quelles leçons à partager?; Presented at the Third Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance Conference; 2005 Oct 10; Dakar, Senegal. welcome address. [Google Scholar]

- 58.National AIDS Control Council of Kenya, Office of the President, Kenya. UNGASS 2008 country report for Kenya. Nairobi: NACC, Office of the President, Kenya; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.National AIDS Control Council of Kenya, Population Council. The overlooked epidemic: addressing HIV prevention and treatment among men who have sex with men in sub-Saharan Africa, report of a consultation. Nairobi: Population Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]