SYNOPSIS

From 1997 through 2007, the Horizons program conducted research to inform the care and support of children who had been orphaned and rendered vulnerable by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in sub-Saharan Africa. Horizons conducted studies in Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Research included both diagnostic studies exploring the circumstances of families and communities affected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and evaluations of pioneering intervention strategies. Interventions found to be supportive of families included succession planning for families with an HIV-positive parent, training and supporting youth as caregivers, and youth mentorship for child-headed households. Horizons researchers developed tools to assess the psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV and outlined key ethical guidelines for conducting research among children. The design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based interventions for orphans and vulnerable children continue to be a key gap in the evidence base.

Studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa in the early 1990s documented a rise in the number of orphans and the breakdown of protective social networks and supports for them.1,2 In 1997, the first comprehensive global estimates of orphans revealed that the number of orphans was increasing and that experience responding to orphaning as a social problem was limited.3

As an initial response, some international and local agencies established orphanages. Child advocates soon criticized this approach as inefficient and unsustainable, undermining traditional models of family and community care, and creating adverse psychological and social effects among children and families.4,5 Concurrently, many program implementers began to recognize what communities had long noted: that children whose parents had died of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were not the only children affected by the epidemic. The operational term “orphans and vulnerable children” (OVC) was thus coined to include not only children orphaned by their parents' death, but also children considered vulnerable to shocks endangering their health and well-being, including living with a chronically ill parent.

As the numbers of vulnerable children steadily grew, so did the demand for greater knowledge about the lives and needs of OVC, their families, and their caregivers. The United Nations' Millennium Development Goals, the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, and other important health and development initiatives incorporated OVC programming into their platforms. Yet, little research had been done and few tools were available to measure the psychosocial manifestations of vulnerability and to evaluate approaches to reduce these negative outcomes. There were too few empirical data to address the key questions of what works in providing care and support to children and families, and how to do it.6–8

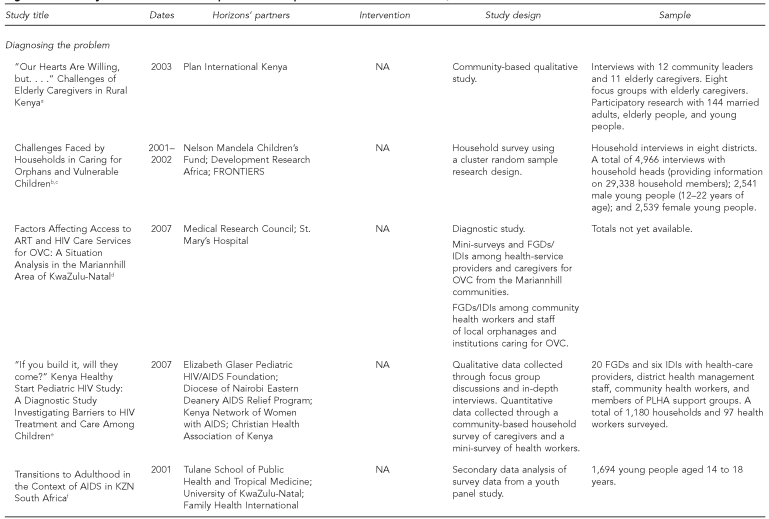

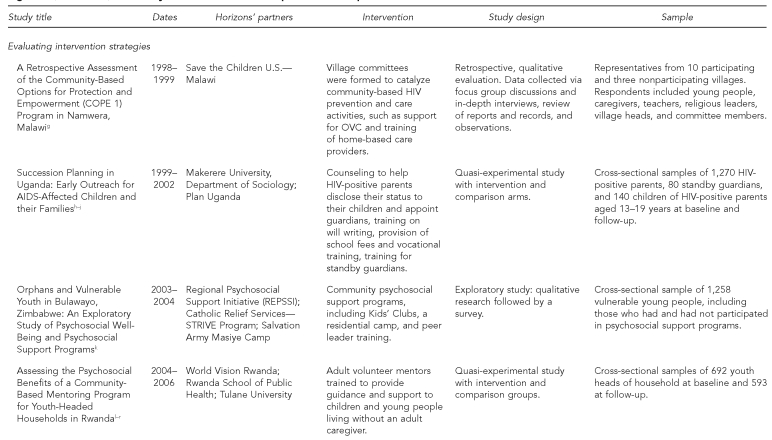

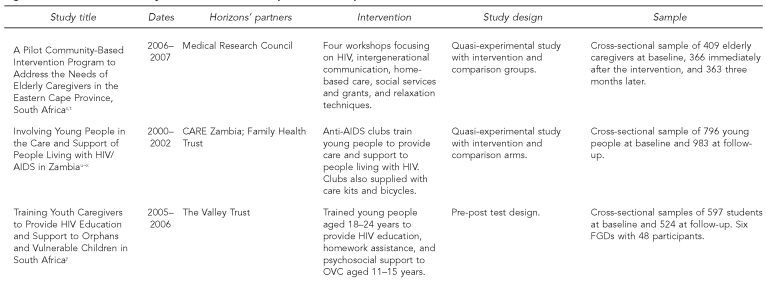

Against this backdrop, in 1997 Horizons began an ambitious program of operations research, which included a focus on the care and support of orphans and other children rendered vulnerable by AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. These studies (Figure 1) were conducted in collaboration with numerous local and international research and program implementation partners in several countries.

Figure 1.

Summary of Horizons' research portfolio on orphans and vulnerable children, 1997–2007

aJuma M, Okeyo T, Kidenda G. “Our hearts are willing, but. . . .” Challenges of elderly caregivers in rural Kenya. Horizons Research Update. Nairobi: Population Council; 2004.

bVermaak K, Mavimbela N, Chege J, Esu-Willams E. Vulnerability and intervention opportunities: research findings on youth and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2004.

cVermaak K, Mavimbela N, Chege J, Esu-Willams E. Challenges faced by households in caring for orphans and vulnerable children. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2004.

dReddy P, James S. Factors affecting access to ART and HIV care services for OVC: a situation analysis in the Mariannhill area of KZN, South Africa. Washington: Population Council; 2008. (AUTHOR TO VERIFY)

eKiragu K, Schenk K, Murugi J, Sarna A. “If you build it, will they come?” Kenya healthy start pediatric HIV study: a diagnostic study investigating barriers to HIV treatment and care among children. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

fThurman TR, Brown L, Richter L, Maharaj P, Magnani R. Sexual risk behavior among South African adolescents: is orphan status a factor? AIDS Behav 2006;10:627-35.

gEsu-Williams E, Duncan J, Phiri S, Chilongozi D. A retrospective assessment of the COPE 1 Program in Namwera, Malawi. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2000.

hHorizons, Makerere University Department of Sociology, Plan/Uganda. Succession planning in Uganda: early outreach for AIDS-affected children and their families. Washington: Population Council; 2004.

iGilborn LZ, Nyonyintono R, Kabumbuli R, Jagwe-Wadda G. Making a difference for children affected by AIDS: baseline findings from operations research in Uganda. Washington: Population Council; 2001.

jHorizons. Succession planning in Uganda: early outreach for AIDS-affected children and their families. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

kGilborn L, Apicella L, Brakarsh J, Dube L, Jemison K, Kluckow M, et al. Orphans and vulnerable youth in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: an exploratory study of psychosocial well-being and psychosocial support programs. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2006.

lBrown L, Thurman TR, Snider L. Strengthening the psychosocial well-being of youth-headed households in Rwanda: baseline findings from an intervention trial. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2005.

mBrown L, Thurman TR, Kalisa E, Rice J, de Dieu Bizimana J, Boris N, et al. Supporting volunteer mentors: insights from a mentorship program for youth-headed households in Rwanda. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

nBrown L, Rice J, Boris N, Thurman TR, Snider L, Ntaganira J, et al. Psychosocial benefits of a mentoring program for youth-headed households in Rwanda. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007.

oThurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, Kalisa E, Nkunda Mugarira E, Ntaganira J, et al. Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care 2006;18:220-9.

pBoris NW, Thurman TR, Snider L, Spencer E, Brown L. Infants and young children living in youth-headed households in Rwanda: implications of emerging data. Infant Mental Health J 2006;27:584-602.

qBoris NW, Brown LA, Thurman TR, Rice JC, Snider LM, Ntaganira J, et al. Depressive symptoms in youth heads of household in Rwanda: correlates and implications for intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:836-43.

rThurman TR, Snider LA, Boris NW, Kalisa E, Nyirazinyoye L, Brown L. Barriers to the community support of orphans and vulnerable youth in Rwanda. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1557-67.

sReddy P, James SJ, Esu-Williams E, Fisher A. “Inkala ixinge etyeni: trapped in a difficult situation:” the burden of care on the elderly in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Horizons Research Update. Johannesburg: Population Council; 2005.

tReddy P, James S, Mutumba Bilay-Boon H, Williams E, Khan H. A pilot community-based intervention program to address the needs of elderly caregivers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2009.

uEsu-Williams E, Schenk KD, Geibel S, Motsepe J, Zulu A, Bweupe P, et al. “We are no longer called club members but caregivers”: involving youth in HIV and AIDS caregiving in rural Zambia. AIDS Care 2006;18:888-94.

vEsu-Williams E, Schenk K, Motsepe J, Geibel S, Zulu A. Involving young people in the care and support of people living with HIV and AIDS in Zambia. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2004.

wEsu-Williams E, Searle C, Zulu A. Involving young people in the care and support of people living with HIV in Zambia: an evaluation of program sustainability. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

xEsu-Williams E, Geibel S, Motsepe J, Schenk K, Zulu M, Bweupe P. Involving youth in the care and support of people affected by HIV and AIDS. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2003.

yNelson TC, Esu-Williams E, Mchunu L, Nyamakazi P, Mnguni S, Schenk K, et al. Training youth caregivers to provide HIV education and support to orphans and vulnerable children in South Africa. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008.

NA = not applicable

ART = antiretroviral therapy

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

OVC = orphans and vulnerable children

FGD = focus group discussion

IDI = in-depth interview

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

PLHA = people living with HIV and AIDS

This article summarizes the key contributions of the Horizons OVC research portfolio in describing the impacts of the epidemic on children, assessing the effectiveness of community-based interventions, identifying insights from program implementation, and improving methods for researching OVC programs and issues. Based on this information, this article concludes with evidence-based recommendations for future programming and research aimed at mitigating the negative effects of AIDS on children, families, and communities.

DIAGNOSING THE PROBLEM

As Horizons began to develop its research agenda, it became clear that there were large gaps in our understanding of how AIDS affects children, which subgroups were particularly vulnerable, and how caregivers were coping. This missing information was critically important to identify which populations to target and to develop interventions to address the most serious problems.

Psychosocial distress

Horizons research quantified the extent to which children affected by AIDS experience psychosocial distress. In a study in Rwanda, 55% of young people who were the heads of their households reported symptoms of clinical depression using standardized depression scales. Many young people in the study reported that their parents' deaths had negatively affected their confidence in other people, the meaning they placed on their own lives, and their religious beliefs. More than half reported feeling that life was no longer worth living at least some of the time, and 4% had attempted suicide in the two months preceding the survey.9 In a study in Zimbabwe, vulnerable young people reported experiencing multiple traumatic events, including the death of loved ones, illness in the family, stigma, rejection in times of need, and the absence of adults to talk to about relationships and problems. More than half of the young people surveyed reported feelings of worry or stress, irritability, sadness, difficulty concentrating, being overwhelmed, and hopelessness during the past month.10

Lack of adult support

Horizons studies identified adult support as an important missing link in the psychosocial well-being of vulnerable children and adolescents. In a study in Zimbabwe, young people emphasized the need to talk with adults about relationships, but many felt that adults did not acknowledge the challenges their generation faces in dealing with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and felt belittled when trying to discuss romantic relationships. In some cases, family disputes—often about property or other resources—alienated them from the adult relative to whom they would normally go for advice. Half of the respondents felt that the adults in their lives did not consistently support them.10

Risks and vulnerability

Research also enumerated the wide range of health risks and limited access to material and social resources experienced by orphaned children. At three rural sites in South Africa, a Horizons study found that orphans were more likely to leave school than non-orphans and were more likely than their peers to cite financial constraints and sickness as the reason for dropping out.11 Horizons also documented risky sexual behaviors among orphans in communities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, including a younger age of sexual debut and a higher rate of transactional or survival sex, compared with non-orphans.12

The death of a parent is not the only driver of vulnerability. An important finding documented by Horizons and its partners was that children's vulnerability often begins once a parent is diagnosed as HIV-positive or becomes ill. For example, in a study in Uganda, about one-fourth of older children (aged 13 to 18 years) with HIV-positive parents reported a decline in school attendance (26%) and performance (28%) when parents became ill. The study also found that many parents had not taken key steps to inform and protect their children should they become ill and die, such as disclosing their HIV status, appointing a guardian, and writing a will.13

Gender and age

Horizons studies in several settings found that being female may also increase vulnerability. In South African communities highly affected by HIV, girls were more likely than boys to be out of school regardless of whether they had been orphaned.11 Similarly, Horizons studies among vulnerable young people in Rwanda,14,15 Zimbabwe,10 and South Africa12 have shown that girls may be more likely than their male counterparts to report negative symptoms and experiences, including depression, traumatic life events, poor appetite, fatigue, hopelessness, and low self-esteem, and to report their first sexual intercourse as unwilling. Women and girls also take on a disproportionate share of the burden of caring for orphans and vulnerable children in many settings, which can have negative repercussions for their own health and well-being.16,17 A Horizons study conducted in eight districts in South Africa found that female-headed households were more likely to include OVC than male-headed households.11,18

Age is also important when considering vulnerability. A Horizons study in Zimbabwe found that older children had higher trauma scores and exhibited more signs of psychosocial distress—such as feeling alone in the world, hopeless, and worried—than their younger peers.10 These results may reflect the challenges and responsibilities—such as unemployment and caring for younger siblings—that befall many older children.

Elderly caregivers

In communities that are deeply affected by AIDS, care for OVC falls heavily on the elderly, especially elderly women. In Kenya and South Africa, Horizons studies found that the demanding tasks of caring for the sick, for the children of those chronically ill, and for orphans can compromise older caregivers' emotional well-being and encroach on time available for involvement in social and economic activities. Also, older adults often lack adequate knowledge, skills, and resources needed for caregiving, and feel significant stress about their own mortality and the future of their children. Elderly caregivers in South Africa reported feeling that they have little influence on the behavior of young people, sometimes expressing a sense of confusion and hopelessness.19 Despite these burdens, many caregivers interviewed in Kenya and South Africa cited a sense of satisfaction in caring for ill adults and their young family members, and the belief that they are doing the best they can.19,20

Still, children may face significant hardships when raised by elderly caregivers. In Kenya, Horizons found that children who depend upon elderly caregivers often drop out of school and are delegated inappropriate workloads (e.g., carrying heavy loads and caring for younger children). Also, some children may experience inadequate or inappropriate levels of discipline.20

Pediatric HIV infection

Children who have experienced parental death from HIV are themselves at particular risk of exposure to perinatal HIV transmission. While still limited, pediatric HIV services are increasingly becoming available to help these highly vulnerable children. However, diagnostic studies conducted in Kenya and South Africa by Horizons in collaboration with partners already implementing pediatric HIV services have documented several obstacles that interfere with children's access to testing and treatment. These include limited community awareness of the indications for HIV testing among children; parental fear that if their children test HIV-positive, their own serostatus will be publicly revealed, thus exposing them to stigma; and such feelings as fatalism and loss of hope among surviving parents and guardians.21,22

EVALUATING INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

These findings helped inform a number of evidence-based intervention strategies that Horizons and its partners developed and tested through operations research. Specifically, results from these studies showed that interventions for vulnerable children need to begin before parental death; address the psychosocial needs of children, including their need for adult support and, in some cases, clinical services; provide caregivers with training, assistance, and emotional support, including family caregivers such as the elderly and community volunteers; and engage community members in decision-making to foster program ownership.

Succession planning

In Uganda, researchers assessed a succession planning program that aimed to reduce uncertainty and fear among adults and children about the children's future well-being. The program provided counseling to HIV-positive parents on disclosure to children, support for appointing standby guardians, training in legal literacy and will writing, and training and seed money for income-generating activities. The Horizons study documented significant increases among parents in the appointment of guardians, a doubling in the number of wills written, and an increase in HIV serostatus disclosure to children. These results prompted international agencies and donors to acknowledge the importance of this approach and recommend scale-up.

Adult mentors for child-headed households

The need for appropriate adult support to improve psychosocial well-being was the main rationale for developing and testing an adult mentorship model in Rwanda. Research found that through regular home visits, trained adult volunteers developed stable, caring relationships with children and adolescents living without an adult caregiver. Despite high levels of depression, maltreatment, and marginalization, and low levels of adult support reported at baseline, follow-up data indicated greater positive psychosocial changes after two years among young heads of households who had been supported by adult volunteers, in contrast to a comparison group not in contact with mentors.14,15 Results also underscored the importance of frequent visits from adult mentors to foster positive relationships: data suggested that household heads perceived the greatest benefits when the mentors visited them and their siblings at least twice a month. The researchers concluded that building connections between adult mentors and young people takes time, but can be a powerful strategy for improving psychosocial outcomes.

Training young people as volunteer caregivers

Horizons studies in Zambia and South Africa demonstrated the feasibility and value of building the capacity of young people to serve as volunteer caregivers within their communities. Although a program in Zambia initially aimed to train young people to help care for adults suffering from chronic illness, it became apparent that many of the youth caregivers spent considerable time supporting children in these AIDS-affected households by providing counseling, help with homework and chores, and assistance in navigating health and education services. Youth caregivers also reported that regular visits to these households helped decrease stigmatization of their HIV-infected clients by family and community members.23,24 In South Africa, trained youth caregivers provided psychosocial support and HIV education to primary school students living in vulnerable settings. Horizons' evaluation found that students' participation in the program was associated with improved HIV-related knowledge, more frequent communication about AIDS, and more accepting attitudes toward people infected and affected by HIV.

These studies also found that young people benefited from their participation in caregiving programs. In Zambia and South Africa, youth caregivers reported that they had gained valuable skills and knowledge in first aid, counseling, and creating linkages with the health and education sectors.23–25 Youth caregivers also improved their own risk behaviors. In Zambia, survey data showed that condom use increased among sexually active young people after they had participated in the program.24,25 Qualitative data revealed that youth caregivers gained satisfaction from serving their communities and earning respect from local leaders. Program staff and stakeholders reported that young people were easy to train as caregivers and were flexible about their availability and the type of household work they carried out, including domestic chores. Male caregivers showed a remarkable willingness to participate equally in caregiving activities. This may have been due to the training they received, which challenged traditional gender roles in caregiving and highlighted the positive role males can play as caregivers.23,24

Addressing the needs of elderly caregivers

Based on formative research findings in South Africa that highlighted the substantial caregiving burden borne by the elderly,19 Horizons and its partners piloted a community-based intervention to address the needs of elderly caregivers and barriers to providing high-quality care. The intervention consisted of a series of workshops on intergenerational communication, basic nursing care, how to gain access to social services and grants, and relaxation techniques. Study findings revealed that elderly caregivers who participated in the intervention experienced improved knowledge about HIV, increased self-esteem, less anxiety about the future, and reduced anger toward their dependents. Further, elderly caregivers reported gaining valuable new skills from the workshops, such as how to better communicate with young people.26

Linkages with community resources and clinical services

Horizons studies emphasized the importance of networking to link OVC programs with existing community resources and clinical services. In Zambia, partnerships with local health and social welfare institutions legitimized the efforts of youth caregivers and extended the scope of activities beyond what they could have carried out alone.23,24 Such partnerships provided youth caregivers with supplies for caregiving (including gloves, bandages, and medications) and with school fees and materials for their clients' children, while capacity-building activities developed their ability to generate resources. Partnerships with local community groups and institutions also provided crucial elements of support and reinforcement to other volunteer caregivers. For example, home-based care providers in Malawi sought communication and collaboration with village health committees, church groups, and traditional healers,27 while adults from home-based care programs in Zambia provided valuable mentoring and support to volunteer youth caregivers.24 In South Africa, elderly caregivers benefited from workshops conducted as a result of collaboration among health, social development, and community organizations.26

Another reason why it is important for OVC programs to link with services in the community is that some children may need more intensive individualized attention than community programs can typically provide. While community-based, psychosocial support programs and caregiving interventions—such as the interventions Horizons evaluated in Rwanda,14,15 Zimbabwe,10 Zambia,23,24 and South Africa25—have proven beneficial to many participants, these programs may not be able to improve all aspects of all participants' health and well-being, either because individual children react to trauma in different ways or because some communities are hit especially hard by larger social forces. To fill these gaps, program implementers should forge linkages with clinical services and community resources. Broader program and policy responses to address economic and sociocultural factors contributing to trauma and psychosocial distress are also needed.

Support for volunteer caregivers

To reduce program costs and make the most of existing resources, many programs train volunteers as adjunct caregivers. Horizons' evaluation data support the value of this approach, but also emphasize the importance of providing ongoing training, support, and incentives to motivate caregivers and sustain high-quality programs.

In Zambia and South Africa, trained youth caregivers reported experiencing stress and emotional distress when caring for AIDS-affected children, particularly when confronted by family disputes, funeral arrangements, and food shortages.23,24 These volunteers benefited from support the programs provided to them and referrals to more comprehensive community services when needed. Training and ongoing support must prepare caregivers for the limitations of their role, and help them spell out more clearly to their clients what they can and cannot provide.

Lack of recognition and recompense for volunteer caregivers can be barriers to long-term program sustainability.25,27,28 In South Africa, the attrition rate among volunteer youth caregivers was high due to lack of financial reimbursement and transportation, and to “poaching” from competing nongovernmental organizations.25 But in Rwanda, very few adult mentors dropped out of the mentorship program for youth-headed households during an 18-month period. The program implementers in Rwanda found that involving the adult volunteers in key program decisions, holding monthly support meetings, formally recognizing and appreciating the volunteers' work, and providing access to income-generating opportunities all contributed to high volunteer retention rates.14

Engaging community members and stakeholders

Horizons' studies illustrate the importance of the participation of local community members and stakeholders (including community leaders, parents/guardians, and teachers) at each step of program development and implementation. The mentorship program in Rwanda demonstrated that giving the volunteer adult mentors decision-making power to set direction for the program catalyzed broader community support for OVC and helped sustain activities.14,15

RESEARCH METHODS AND ETHICS

To carry out its research agenda, Horizons recognized that there were methodological and ethical gaps in conducting research on OVC issues. Through its work in sub-Saharan Africa, Horizons has contributed to the development of research measures and ethical guidelines that have helped the field better understand and measure the psychosocial dimensions of vulnerability, develop and test responses to improve psychosocial outcomes, and protect children while collecting data for these purposes.

Measuring psychosocial well-being

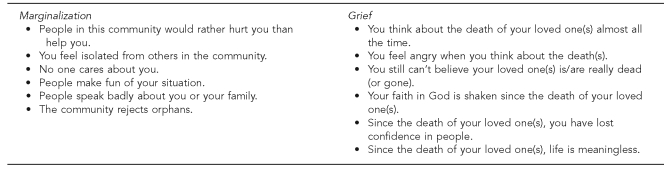

In Uganda and Zimbabwe, researchers developed, tested, and refined measures of psychosocial well-being,10,13 which informed later research in Rwanda that tested new measures of social support, grief, maltreatment, and marginalization.15Figure 2 shows items from the grief and marginalization scales29,30 that were part of the instrument used to examine the impact of an adult mentorship program on youth-headed households.

Figure 2.

Examples of the statements used for the marginalization and grief scalesa of a Horizons study measuring psychosocial well-being among young people aged 13–24 in Rwanda who were responsible for their householdsb,c

aEach item was scored on a five-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

bThurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, Kalisa E, Nkunda Mugarira E, Ntaganira J, et al. Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care 2006;18:220-9.

cBrown L, Thurman TR, Rice J, Boris NW, Ntaganira J, Nyirazinyoye L, et al. Impact of a mentoring program on psychosocial well-being of youth-headed households in Rwanda: results of a quasi-experimental study. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 2009;4:288-99.

Ethical guidelines for research with children

Recognizing that methods used for conducting social and behavioral research among adults are inappropriate for research among children affected by HIV, Horizons spearheaded the development of a guidance document31 that highlights the responsibilities of research and program staff to ensure that child-related activities are conducted ethically so as to safeguard children's health, well-being, and rights. Developed through a multidisciplinary, international, consultative process under the leadership of a steering committee that included representatives of the U.S. Agency for International Development and the United Nations Children's Fund, this pioneering document identifies challenges confronting program implementers and investigators, and proposes practical solutions, illustrated with case studies and complemented by a comprehensive resource list. The document draws on the experiences of Horizons and other researchers in various countries who grappled with such ethical issues as the use of comparison groups in intervention studies, seeking consent for children's participation in research when their parents are dead, maintaining confidentiality and anonymity, and avoiding the stigmatization of vulnerable children when targeting them for data collection and intervention activities.32

MOVING FORWARD: RESEARCH AND PROGRAM PRIORITIES

As Horizons wraps up a decade of OVC research, how will its pioneering efforts help inform and encourage future OVC research and programs? Evidence from the Horizons OVC portfolio indicates that the practical and ethical challenges of conducting research among children in vulnerable circumstances are not insurmountable obstacles to the rigorous evaluation of OVC interventions. Horizons studies have demonstrated that diagnostic studies and sound evaluations of community-based interventions are not only possible, but yield rich findings; quasi-experimental designs with process evaluations provide valuable and scientifically valid frameworks for building the empirical data on OVC care and support programs.

Horizons' studies have made substantial contributions to a nascent field, documenting a range of HIV-related impacts that critically affect the health and well-being of OVC, and demonstrating that programs can make a tangible difference in the lives of children and families affected by AIDS. Horizons' OVC research findings highlight the value of adult support and guidance, the need to focus on the particular circumstances of females and the elderly, the importance of meeting ethical standards in research among children who are vulnerable, and the fundamental understanding of vulnerability as broader than orphanhood. They also underscore the potential of community members—including young people and adults—to be part of the solution to the problems facing AIDS-affected families.

Horizons' research indicates that future program priorities must include the development of functional linkages between OVC care and support interventions and other key services for young people such as HIV-prevention and life-skills education; health services, including access to antiretroviral treatment; and livelihood support. A focus on linkages, referrals, and, where appropriate, program integration can help service providers meet the multiple as well as gender-specific needs of vulnerable youth while safeguarding their rights, and may also contribute to greater program coverage and efficiency. Additionally, proactive engagement with community members, networking and capacity-building of local organizations, and systematic priority-setting are key to long-term program sustainability.

Yet, important work remains to be done. The evaluation of community-based OVC interventions continues to be a key gap in the literature. Developing and scaling up appropriate interventions requires research guided by the input of community members and stakeholders to ensure that programs are achieving their desired goals without harming children or jeopardizing their rights. The resulting data will enable program implementers, policy makers, and donors to decide which strategies are most effective and how they should be implemented. While investment in rigorous evaluation is initially resource intensive, the long-term payoff of developing a solid evidence base will ensure that future spending is directed at producing better outcomes among more children.

Footnotes

The Horizons research studies reviewed in this article were conducted in collaboration with local implementing and research partners, whose cooperation and input were vital. The authors extend special thanks to Age-In-Action, Medical Research Council, and the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund/Goelama Project in South Africa; CARE, Catholic Archdiocese of Ndola, Catholic Diocese of Mansa, and Family Health Trust in Zambia; Catholic Relief Services/STRIVE Program, Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative, and Salvation Army/Masiye Camp in Zimbabwe; Diocese of Luwero, Grasslands, Makerere University, and National Community of Women Living with AIDS in Uganda; Plan International in Uganda and Kenya; Rwanda School of Public Health and World Vision in Rwanda; and Save the Children in Malawi. The authors also thank Laelia Gilborn, LeeAnn Jones, Hena Khan, Naomi Rutenberg, and Tonya Thurman for their constructive contributions.

These studies were made possible by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00012-00. The contents of this article are the responsibility of the Population Council and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunter SS. Orphans as a window on the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa: initial results and implications of a study in Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:681–90. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90250-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preble EA. Impact of HIV/AIDS on African children. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:671–80. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90249-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter S, Williamson J. Children on the brink: strategies to support children isolated by HIV/AIDS. Washington: USAID; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn A, Jareg E, Webb D, HIV/AIDS Coordinating Group of the International Save the Children Alliance A last resort: the growing concern about children in residential care: Save the Children's position on residential care. 2003. [cited 2009 Oct 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.savethechildren.net/alliance/resources/publications.html.

- 5.Foster G, Shakespeare R, Chinemana F, Jackson H, Gregson S, Marange C, et al. Orphan prevalence and extended family care in a peri-urban community in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1995;7:3–17. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savedoff WD, Levine R, Birdsall N, Center for Global Development, Evaluation Gap Working Group . Improving lives through impact evaluation. Washington: Center for Global Development; 2006. May, When will we ever learn? [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel M. A meta-evaluation, or quality assessment, of the evaluations in this issue, based on the African Evaluation Guidelines: 2002. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2002;25:329–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenk KD. Community interventions providing care and support to orphans and vulnerable children: a review of evaluation evidence. AIDS Care. 2009;21:918–42. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown L, Thurman TR, Snider L. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2005. Strengthening the psychosocial well-being of youth-headed households in Rwanda: baseline findings from an intervention trial. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilborn L, Apicella L, Brakarsh J, Dube L, Jemison K, Kluckow M, et al. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2006. Orphans and vulnerable youth in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: an exploratory study of psychosocial well-being and psychosocial support programs. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermaak K, Mavimbela N, Chege J, Esu-Willams E. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2004. Vulnerability and intervention opportunities: research findings on youth and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thurman TR, Brown L, Richter L, Maharaj P, Magnani R. Sexual risk behavior among South African adolescents: is orphan status a factor? AIDS Behav. 2006;10:627–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horizons, Makerere University Department of Sociology, Plan/Uganda. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2004. Succession planning in Uganda: early outreach for AIDS-affected children and their families. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown L, Thurman TR, Kalisa E, Rice J, de Dieu Bizimana J, Boris N, et al. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Supporting volunteer mentors: insights from a mentorship program for youth-headed households in Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown L, Rice J, Boris N, Thurman TR, Snider L, Ntaganira J, et al. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2007. Psychosocial benefits of a mentoring program for youth-headed households in Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden J, Esim S, Grown C. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council and International Center for Research on Women; 2004. Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogden J, Esim S, Grown C. Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:333–42. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermaak K, Mavimbela N, Chege J, Esu-Willams E. Horizons Research Update. Washington: Population Council; 2004. Challenges faced by households in caring for orphans and vulnerable children. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy P, James SJ, Esu-Williams E, Fisher A. Horizons Research Update. Johannesburg: Population Council; 2005. “Inkala ixinge etyeni: trapped in a difficult situation”: the burden of care on the elderly in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juma M, Okeyo T, Kidenda G. Horizons Research Update. Nairobi: Population Council; 2004. “Our hearts are willing, but. . . .” Challenges of elderly caregivers in rural Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy P, James S. Factors affecting access to ART and HIV care services for OVC: a situation analysis in the Mariannhill area of KZN, South Africa. Washington: Population Council; 2010. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiragu K, Schenk K, Murugi J, Sarna A. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2008. “If you build it, will they come?” Kenya healthy start pediatric HIV study: a diagnostic study investigating barriers to HIV treatment and care among children. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esu-Williams E, Schenk KD, Geibel S, Motsepe J, Zulu A, Bweupe P, et al. “We are no longer called club members but caregivers”: involving youth in HIV and AIDS caregiving in rural Zambia. AIDS Care. 2006;18:888–94. doi: 10.1080/09540120500308170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esu-Williams E, Schenk K, Motsepe J, Geibel S, Zulu A. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2004. Involving young people in the care and support of people living with HIV and AIDS in Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson TC, Esu-Williams E, Mchunu L, Nyamakazi P, Mnguni S, Schenk K, et al. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Training youth caregivers to provide HIV education and support to orphans and vulnerable children in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy P, James S, Mutumba Bilay-Boon H, Williams E, Khan H. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2009. A pilot community-based intervention program to address the needs of elderly caregivers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esu-Williams E, Duncan J, Phiri S, Chilongozi D. Horizons Final Report. Washington: Population Council; 2000. A retrospective assessment of the COPE 1 Program in Namwera, Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esu-Williams E, Searle C, Zulu A. Horizons Research Summary. Washington: Population Council; 2008. Involving young people in the care and support of people living with HIV in Zambia: an evaluation of program sustainability. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, Kalisa E, Nkunda Mugarira E, Ntaganira J, et al. Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care. 2006;18:220–9. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown L, Thurman TR, Rice J, Boris NW, Ntaganira J, Nyirazinyoye L, et al. Impact of a mentoring program on psychosocial well-being of youth-headed households in Rwanda: results of a quasi-experimental study. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2009;4:288–99. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schenk K, Williamson J. Ethical approaches to gathering information among children and adolescents in international settings: guidelines and resources. Washington: Population Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schenk K, Murove T, Williamson J. Protecting children's rights in the collection of health and welfare data. Health Hum Rights. 2006;9:80–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]