Sexual health education (SHE) is an important strategy for promoting well-informed sexual decision-making and preventing unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents.1–4 One promising approach for increasing adolescent SHE access is to institute school district policies that mandate high-quality sex education.5 In partnership with youth activists organized by the Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health (ICAH), the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Board of Education established such a policy in April 2006.6

Called Family Life and Comprehensive Sexual Health Education, the CPS SHE policy commits to providing district students with sex education that is comprehensive, age appropriate, medically accurate, and emphasizes abstinence while not excluding information about using condoms and other techniques for preventing unintended pregnancies and STIs. Individual schools have the discretion to meet the policy's guidelines by using curricula and programs that are best suited for local needs. In addition, the policy requires that (1) any teacher delivering SHE instruction participate in a relevant CPS training and (2) schools using outside consultants for SHE instruction ensure that these providers are district-approved. While the policy created these guidelines for its implementation, it did not contain language specifying school-level monitoring, evaluation, or accountability. A recent literature synthesis indicates that without such accountability mechanisms, policy implementation is likely to be sporadic at best.7

Though the SHE policy was an impressive first step for increasing adolescent access to high-quality sex education in CPS, ICAH advocates noted that 1.5 years after its adoption, this policy was not being fully implemented district-wide (Personal communication, Jonathan Stacks, Director of Sexual Health Education Initiatives, ICAH, March 2009). This finding was not surprising, as few resources exist (at the national, state, or local levels) to guide schools' implementation of sex education programming. Data from an informal survey conducted by CPS indicated that most school personnel responsible for SHE were not aware of the district's policy. In addition, while some schools were implementing high-quality sex education programs, others were delivering abstinence-only curricula based on the availability of federal funds or local providers, and some schools were not implementing any sex education program. As a result, ICAH partnered with CPS and a team from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) School of Public Health (SPH) to design and execute the Policy to Practice (PTP) study during the 2007–2008 school year. The CPS-PTP study sought to answer an overarching question: “What are the barriers and supports to implementing the CPS SHE policy in local schools?” The ultimate goal of CPS-PTP is to provide guidance for the school district as it seeks to support greater implementation of its policy in local schools.

THE ACADEMIC-COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP

Partner descriptions

CPS-PTP is a partnership among three organizations: CPS, ICAH, and UIC SPH. Since this study's completion, the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) has made adolescent pregnancy and STI prevention a priority area. Thus, while CDPH did not directly participate in CPS-PTP, we anticipate that it will partner with CPS to use study results. Following is a brief description of each participating partner.

CPS is the third-largest school district in the country. Comprising 666 schools (483 elementary schools, 116 high schools, and 67 noncategorized schools), the district serves 407,955 students from a diverse range of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Its guiding principles are to educate, inspire, and transform (http://www.cps.edu). Sex education is typically offered as part of a 20-week health curriculum delivered in the ninth grade (high school) or integrated across other curricular areas in elementary schools.

ICAH is a 32-year-old nonprofit agency based in Chicago whose mission is to “advocate for sound policies and practices that promote a positive approach to adolescent sexual health and parenting in partnership with youth” (http://www.icah.org). To fulfill this mission, ICAH has recently begun advocating for changes to school district sex education policies in multiple sites across Illinois. While conducting these advocacy efforts, ICAH has recognized that policy change must lead to implementation to be effective and, thus, is increasingly focused on helping districts support sex education delivery in schools.

According to its mission statement, UIC SPH “is dedicated to excellence in protecting and improving the health and well-being of the people of the metropolitan Chicago area, the State of Illinois, the nation, and of others throughout the world” (http://www.uic.edu/sph). This mission is achieved in part by educating future public health professionals and conducting solutions-oriented research. UIC SPH is heavily involved in applied health promotion efforts that often utilize links with external partners.

Partnership strategy

Because neither ICAH nor CPS had the research infrastructure or resources to conduct the CPS-PTP study alone, they contacted UIC SPH for assistance. Based on a longstanding collaborative relationship between ICAH and Michael Fagen of UIC SPH, the school agreed to take a leading role in CPS-PTP. However, because no external funding was available to conduct CPS-PTP, the partnership needed a creative strategy for study execution.

After several strategy sessions, we agreed to build CPS-PTP data collection and analysis into Dr. Fagen's course in community assessment (Community Health Sciences [CHSC] 431: Community Assessment in Public Health). The primary goal of CHSC 431 is to train master of public health (MPH) students in the concepts and skills of community assessment. This goal is achieved via course learning objectives that allow students to (1) understand fundamental concepts in community and assessment; (2) gain relevant skills in community assessment methods such as key informant interviews, secondary data analysis, and asset mapping; and (3) plan for and present results from an actual community assessment that is part of the course's fieldwork requirement. For the fall 2007 and spring 2008 offerings of CHSC 431, we agreed that CPS-PTP would comprise the course's fieldwork component.

Partner roles

Each partner played an important role in conducting the CPS-PTP study. CPS provided overall approval for the project and wrote a support letter that was used to recruit individual study schools and participants. Moreover, several CPS administrators from the Coordinated School Health Unit (CSHU) committed their time to engage meaningfully in the project by (1) helping to identify schools for study participation, (2) attending CHSC 431 class sessions where CPS-PTP results were discussed, and (3) reviewing drafts of the study's final report. Similarly, ICAH (led by Stacks) provided leadership to design the CPS-PTP study, recruit individual study schools, and author the final report. During the study period, several ICAH staffers (including Stacks) routinely came to CHSC 431 class sessions to clarify data collection and analysis issues and discuss emerging findings. Finally, UIC SPH took the lead in securing human subjects protection (Institutional Review Board approval), designing the CPS-PTP data collection instruments, collecting study data, and generating findings for discussion and interpretation.

METHODS

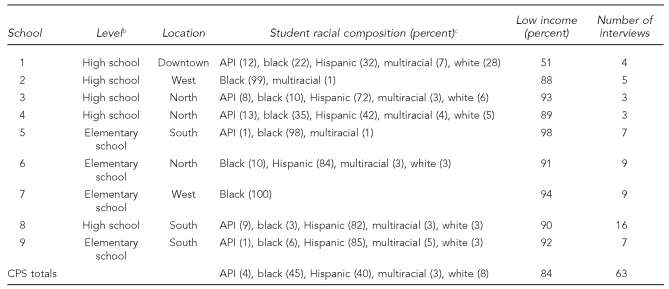

ICAH recruited a total of nine schools for the CPS-PTP study: five high schools (grades nine to 12) and four elementary schools (kindergarten to eighth grade). While not representative of the entire district, these schools were selected to generate a diverse sample based on the following factors: level (elementary school or high school), geographic location in Chicago (north side, south side, west side, or downtown), and racial composition of the student body (predominantly African American, predominantly Hispanic, or mixed). Almost all schools in CPS serve primarily low-income families and have a predominantly African American or Hispanic student body; our study schools were no exception (Table).

Table.

School sample description and number of interviews for the Chicago Public Schools Policy to Practice study, 2007–2008a

aSource: Illinois State Board of Education. eReport card public site [cited 2009 Mar 23]. Available from: URL: http://webprod.isbe.net/ereportcard/publicsite/getSearchCriteria.aspx

bHigh school includes grades nine through 12. Elementary school includes kindergarten through eighth grade.

cSchool total percentages in the Student Racial Composition column may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

API = Asian/Pacific Islander

CPS = Chicago Public Schools

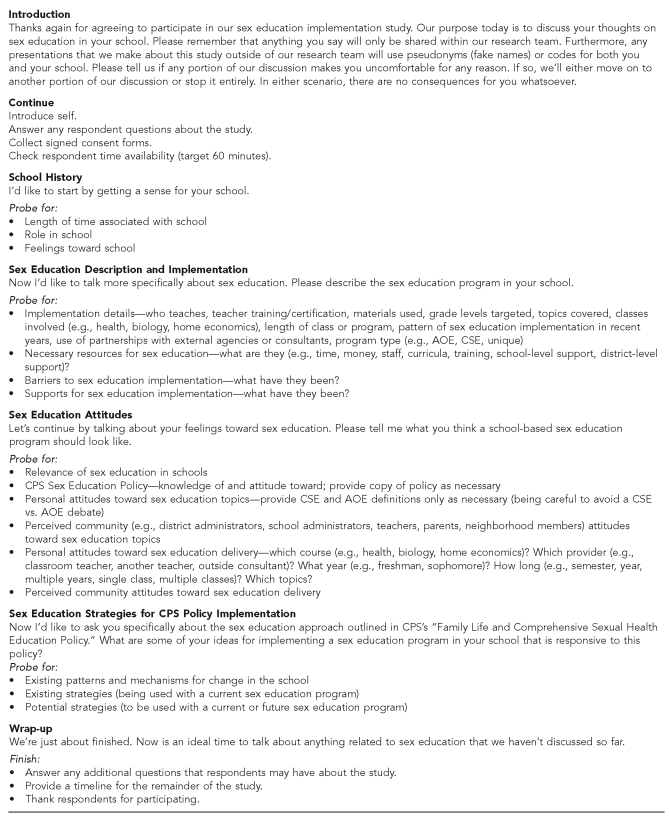

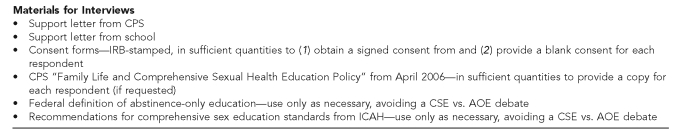

The study's primary data collection method was key informant interviews. A total of 38 CHSC 431 students conducted these interviews in nine small groups of four to five students each (one student group per study school). Using a structured guide developed by Dr. Fagen (Figure), the students interviewed 63 administrators, teachers, other school staffers (e.g., social workers and nurses), parents, and SHE providers to identify barriers to and supports for implementing CPS's SHE policy. The same questions were asked of all interviewees to gain a comprehensive sense for policy implementation in each school. Students generally conducted the interviews in pairs, with one student guiding the conversation and the other taking extensive notes.

Figure.

Key informant interview guide for the Chicago Public Schools Policy to Practice study, 2007–2008

AOE = abstinence-only education

CSE = comprehensive sex education

CPS = Chicago Public Schools

IRB = Institutional Review Board

ICAH = Illinois Caucus for Adolescent Health

The number of participants at each school ranged from three to 16 (Table), and each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. The goal for each school's interviewee sample was to recruit at least one key informant from every stakeholder category (i.e., administrators, teachers, and relevant staffers). We conducted initial participant recruitment via the school principal and recruited subsequent interviewees based on referrals, stakeholder category, and convenience. Overall, students were responsible for recruiting participants, conducting interviews, taking and refining interview notes, generating findings, and sharing results in class with both the CPS and ICAH partners.

Two CHSC 431 students took on additional roles during CPS-PTP's summer 2008 analysis and reporting phases. As an MPH practicum intern (Emily Hutter) and temporary ICAH employee (Laura Syster), these students used qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti)8 to further analyze interview notes and sharpen study findings. Under Dr. Fagen's supervision, these data analysts generated a list of 20 codes (available upon request) that were used to categorize interview data into major barriers to and supports for implementing the SHE policy. After applying these codes during three passes, the analysts reached 81% agreement on code application and full consensus with Dr. Fagen on the study's major findings.

RESULTS

Based on findings from the key informant interviews, school-related personnel identified the following major barriers to implementing the CPS SHE policy:

Lack of time to teach sex education given competing curricular priorities and an emphasis on standardized testing;

Lack of available and convenient sex education training opportunities for teachers;

Lack of available sex education resources such as curricula, textbooks, and handouts;

Competing school and community norms regarding appropriate sex education; and

Lack of a centralized support system for sex education implementation, including dissemination of the SHE policy.

Despite these barriers, school-related personnel were able to identify several major supports for implementing the CPS SHE policy:

Predominantly supportive attitudes toward sex education implementation among all types of school-related personnel;

Dedicated teachers and staffers within each school willing to lead sex education efforts given sufficient resources and supports;

CPS-approved curricula and providers for sex education implementation; and

Existing local resources for sex education implementation such as community-based organizations (CBOs), school-based health clinics, and health-care agencies.

Once these major findings were confirmed by the qualitative data analysis described previously, ICAH took the lead in generating recommendations and convening an external panel of sex education experts to review them. The review panelists were chosen to represent those stakeholder groups that would either be involved in or impacted by CPS sex education implementation. This panel included a CPS elementary school teacher, a CPS nurse, a CPS social worker, a recent CPS high school graduate, a parent of a CPS high school student, an education program officer from a local foundation, the executive director of a local health education center, an educator from a local adolescent health center, and the educational programs coordinator from a local SHE provider. Once reviewed and solidified, the following short-term recommendations were presented to CPS in a final study report:

Increase awareness of the SHE policy and clarify access to existing CPS sex education resources;

Develop a systematic plan for sex education implementation that is sustainable and responsive to key stakeholder needs;

Provide additional financial resources for sex education implementation; and

Build knowledge about successful strategies for sex education implementation within CPS.

The ICAH/UIC SPH team shared these results with CPS administrators and participating study schools in summer 2008. Since then, CPS has been responding to the study's recommendations, initially focusing on building awareness of the SHE policy. Relatedly, ongoing discussions within the partnership were partially responsible for CPS's revision of its SHE policy in August 2008.9 The revised policy contains (1) stronger language about implementing sex education (e.g., “offer” was changed to “provide”), (2) instructions to start sex education implementation earlier (i.e., in fifth rather than sixth grade), (3) articulation of instructional minutes that must be devoted to sex education, and (4) a requirement that principals designate at least one teacher per school for sex education training.

Since approval of the SHE policy, CPS has taken multiple steps to publicize and encourage its implementation. Ongoing conversations between CPS CSHU staffers and local school personnel have emphasized the predominantly supportive attitudes toward sex education that were highlighted in the PTP report. CSHU staff members have used these conversations to dispel certain misperceptions about SHE implementation (e.g., that school staffers will lose their jobs if they teach sex education and that sex education instruction must take an abstinence-only approach). Simultaneously, CSHU staff members have used these encounters to promote awareness of the SHE policy with school personnel.

In addition, the CPS CSHU has built many of the PTP findings and recommendations into its newly revised strategic plan for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention.10 This five-year plan was submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in November 2008 as a requirement for continued CDC funding. The CSHU staffer who led the strategic plan's development had been an active partner in the PTP study and used the PTP report as a fundamental data source. Moreover, this staff member invited the PTP report's lead author from ICAH (Stacks) to serve on the strategic planning committee as an external stakeholder. Because HIV prevention is an important component of SHE implementation, the stage was set to integrate PTP results into CPS's long-term SHE planning.

The following strategies from CPS's HIV Prevention Strategic Plan are based directly on PTP findings and recommendations:

Provide and advertise professional development and training programs for school personnel on HIV/STI and unintended pregnancy prevention education;

Coordinate CBO and other partner collaborations to assist in sex education implementation;

Collaborate with the CDPH and school-based health centers on prevention education and STI testing; and

Centrally locate links to comprehensive SHE resources for teachers and students.

In partnership with ICAH, these strategies are leading to actions. For example, the CPS CSHU is attempting to develop its own website (pending approval and funding) that aims to be user-friendly for school personnel. This site will feature a simple interface for locating training options and links to district-approved resources for sex education (such as curricula and providers). In addition, CSHU conducted a principals institute during summer 2009 that publicized the SHE policy with local school administrators and described the district's array of resources and supports for sex education implementation.

DISCUSSION

CPS's many steps to implement its sex education policy illustrate the power of its partnership with ICAH and UIC SPH. As is the case in most large urban school districts, CPS is challenged to create and execute policies given the size, scope, and diversity of its schools, personnel, and students. We are confident that our partnership is strengthening CPS's ability to develop successful sexual health implementation strategies at both the district and local school levels.

We attribute the success of our efforts to several core factors that are considered essential to effective partnerships.11–13 The first element is trust, which often results from previously established working relationships. Dr. Fagen had served on the ICAH board of directors for six years prior to the PTP study. In addition, several UIC SPH MPH students had completed practica or written capstone papers with ICAH before PTP began. Similarly, both ICAH and Dr. Fagen had worked directly with CPS CSHU personnel on previous projects designed to promote student health. Thus, all of the key personnel in the partnership had collaborated and established trusting professional relationships prior to PTP's inception.

Another important element in effective partnerships is the “win-win” factor. Each partner must feel good about what it will gain from the partnership to willingly participate. The win-win factor for all PTP partners was clear. For ICAH, it was the opportunity to further its mission of promoting access to high-quality SHE for adolescents. For UIC SPH, it was the opportunity for MPH students to be meaningfully involved in a real-life community assessment project that had high potential for resultant action. For CPS, it was the opportunity to catalyze the implementation of its SHE policy.

CONCLUSION

CPS has made considerable strides in revising its SHE policy to strengthen the potential for program implementation. However, it will be important to monitor the progress of implementation itself to assure that quality SHE programs are adopted, delivered, and maintained within the entire CPS system. The progress that CPS has demonstrated thus far largely results from the district's partnership with ICAH and UIC SPH.

Our experience illustrates how a school of public health can tangibly collaborate with multiple agencies to produce change that should ultimately improve adolescent health. Moreover, the partnership's focus on data collection, analysis, and results presentations promoted valuable learning experiences for dozens of MPH students. We hope that our PTP study provides an example for other schools of public health that seek to engage in meaningful academic-community partnerships.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all students in both the fall 2007 and spring 2008 CHSC 431: Community Assessment in Public Health course who collected, analyzed, and presented data for the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Policy to Practice (PTP) study. The authors also thank Vicki Pittman, MS, RN, MA, CPS, Coordinated School Health Manager, whose participation in CPS-PTP and insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article immeasurably strengthened this study and the article.

Footnotes

Michael Fagen received approval for conducting the CPS-PTP study from Internal Review Board #2 at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) (Research Protocol # 2007-0615—School-Based Sex Education Implementation Study) on September 25, 2007.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Medical Association. Sexuality education, abstinence, and distribution of condoms in schools. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyle K, Basen-Engquist K, Kirby D, Parcel G, Banspach S, Collins J, et al. Safer choices: reducing teen pregnancy, HIV, and STDs. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):82–93. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedlow CT, Carey MP. Developmentally appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescents: rationale, review of interventions, and recommendations for research. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:172–84. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Guidelines for effective school health education to prevent the spread of AIDS. [cited 2009 Mar 23]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/guidelines/guidelines.htm.

- 6.Chicago Public Schools. Policy 06-0426-P04. Chicago: Chicago Board of Education; 2006. Family life and comprehensive sexual health education. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa (FL): University of South Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. ATLAS.ti: Version 5.2. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chicago Public Schools. Policy 08-0827-P04. Chicago: Chicago Board of Education; 2008. Family life and comprehensive sexual health education policy. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chicago Public Schools. HIV prevention strategic plan, report DP08-80102. Chicago: Chicago Board of Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hann NE. Transforming public health through community partnerships. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2:A03. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallerstein N, Duran B, Minkler M, Foley K. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. Developing and maintaining partnerships with communities. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.White-Cooper S, Dawkins NU, Kamin SL, Anderson LA. Community-institutional partnerships: understanding trust among partners. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:334–47. doi: 10.1177/1090198107305079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]