Abstract

We previously reported that lacrimal glands (LGs) of male non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, an established mouse model of autoimmune inflammatory LG disease that displays many features of human LGs in patients afflicted with Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS), exhibit significant degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) structures as well as increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The purpose of the current study was to expand the spectrum of proteases identified, to identify their probable origin as well as to clarify the contribution of these changes to disease pathogenesis. We explored in depth the changes in ECM structures and ECM protease expression at the onset of disease (6 weeks) versus late stage disease (18 weeks) in male NOD mouse LGs, relative to age-matched male NOD-scid, a severely immunocompromised congenic strain, and healthy BALB/c mice. LG tissues were examined using routine histological, immunohistochemical, Western Blot and gene expression analyses, as well as with novel multiphoton imaging technologies. We further characterized the profile of infiltrating immune cells under each condition using flow cytometry. Our results show that the initial infiltrating cells at 6 weeks of age are responsible for increased MMP and cathepsin H expression and therefore initiate the LG ECM degradation in NOD mice. More importantly, NOD-scid mice exhibited normal LG ECM structures, indicating the lymphocytes seen in the LGs of NOD mice are responsible for the degradation of the LG ECM. The disease-related remodeling of LG ECM structures may play a crucial role in altering the acinar signaling environment, disrupting the signaling scaffolds within the cells, which are required to mobilize the exocytotic trafficking machinery, ultimately leading to a loss of LG function in patients afflicted with SjS.

Keywords: lacrimal gland, Sjögren’s syndrome, collagen, elastin, extracellular matrix, matrix metalloproteinases

Introduction

Proteases such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and lysosomal cysteine proteinases (cathepsins) play important roles during normal embryonic development, including the morphological development of glandular structures (Thompson et al., 1983; de la Cuadra-Blanco et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2006). Their degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins alters the tissue microenvironment, allowing cellular migration and differentiation (Thompson et al., 1983; Patel et al., 2006); however, numerous studies have demonstrated their close association with various diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis (Xue et al., 2007; Takaishi et al., 2008). Increased levels of MMPs have also been implicated in the progression of the autoimmune disease Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS) in which lymphocytes infiltrate lacrimal (LGs) and salivary glands (SGs) (Perez et al., 2000; Goicovich et al., 2003; Molina et al., 2006; Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). These events lead to atrophy and ultimately destruction of these tissues, resulting in severe dry eye and dry mouth symptoms which are characteristic of this disease state (Fox et al., 1983; Fox, et al., 1986; Matsumoto et al., 1996). Because the LGs are seriously affected, patients cannot produce reflex tears, resulting in severe damage to the ocular surface including squamous metaplasia of the ocular surface epithelium, pain, corneal scarring and in severe cases, blindness (Tsubota et al., 1996).

Although a number of theories have been proposed to explain the onset and progression of lymphocytic infiltration into the LG and SG, the disease is still very poorly understood. The use of mouse models has been important in advancing our knowledge of the etiology of SjS. Perhaps one of the best known models is the male non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse (Robinson et al., 1997; Yamachika et al., 1998; Humphreys-Beher and Peck, 1999; da Costa et al., 2006). This strain spontaneously develops diabetes as well as lymphocytic infiltration in SGs (sialoadenitis) and LGs (dacryoadenitis), an effect that is associated with reduced secretory flow (van Blokland and Versnel, 2002; Barabino and Dana, 2004; da Costa et al., 2006). The two autoimmune processes of diabetes and SjS occur independently in the same animal. For reasons not yet understood, male NOD mice are more susceptible to dacryoadenitis than female mice, whereas SjS is more prevalent in female patients. Lymphocytic infiltration into the LGs, which is accompanied by decreased production of lacrimal fluid, is typically detected in male mice from ~6–10 weeks. The severely immunocompromised congenic strain (NOD-scid) also exhibits abnormalities in SG and LG function (Yamachika et al., 2000; van Blokland et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 1997; Kong et al., 1998), suggesting that the disease process exhibited in this model includes both exocrine tissue-dependent as well as inflammatory cell-dependent events. The comparison between the LGs of NOD and the NOD-scid strains provides a powerful tool for distinguishing processes initiated within the exocrine tissue versus processes initiated by the immune system.

It is clear from different studies of mouse models of SjS that abnormalities in protease activity participate in disease development and progression. For instance, prior to the appearance of glandular infiltrating lymphocytes, aberrant expression of specific apoptotic proteases (caspases) occurs in the salivary gland lysates in NOD mouse LG (Robinson et al., 1997; Yamachika et al., 1998; Yamachika et al., 2000). Another study in a different mouse model of SjS implicated aberrant cathepsin S activation in sialoadenitis, showing that inhibition of cathepsin S was able to prevent SG-specific autoimmunity (Saegusa et al., 2002). Each of these previous studies has linked the enhanced expression of proteases to changes in the acinar cells rather than to immune cell infiltrates. Recently, we were able to demonstrate in the LG of male NOD mice with established disease (e.g., 18 weeks of age) that they exhibited significant degradation of ECM structures, as well as increased expression of MMPs (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). In order to understand the origin of the increased protease levels, as well as the contribution of these changes to disease pathogenesis, we have here explored in depth the changes in ECM structures and ECM protease expression at the onset of disease (6 weeks) versus later stage disease (18 weeks) in male NOD mouse LGs, relative to NOD-scid and BALB/c mice. We have also characterized the profile of the infiltrating immune cells under each condition. Our results show that the initial infiltrating cells at 6 weeks of age, which are responsible for the increased MMP and cathepsin H expression, initiate the ECM degradation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was conducted using LGs isolated from male BALB/c (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor/ME, USA), NOD and NOD-scid (both Taconic Farms, Germantown/NY, USA) mice at the ages of 6 and 18 weeks as previously described (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). All procedures conformed to the standards and procedures for the proper care and use of animals in accordance with the institutional guidelines, and as described in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals (DHEW publication, NIH 80-23).

Routine histology and immunofluorescence analysis

For routine histological and immunofluorescence analyses horizontal cryo-sections (5–8 μm) of the LGs from 6 and 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice were cut, and processed as previously described (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). All specimens were treated and sectioned similarly. Each tissue considered for histological analysis was stained with hematoxylin-eosin. After histological staining, all sections were mounted using Entellan (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield/PA, USA), analyzed and documented using routine bright-field light microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope, equipped with Plan-Neofluar 10x, 20x and 40x objectives; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood/NY, USA).

Immunohistostaining was carried out using immunofluorescence techniques as previously described (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). All images were acquired using an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Semi-quantitative immunofluorescence analysis was performed independently by two researchers using ImageJ software (developed at the National Institutes of Health and available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) as previously described (Humphries et al., 1998; Noursadeghi et al., 2008). In detail, for each antibody, six representative photographs were taken at identical exposure times. The nuclear intensity of staining for individual nuclei was comparable between the samples at this equivalent exposure, confirming that the labeling procedure was successful and evenly distributed across the slides and in the regions of analysis. ECM protein expression in BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LGs was assessed as gray value intensities (GVIs) for each antibody in I.) total extracellular regions of interest (ROI1), and II.) the tissue structure-specific regions of interest (ROI2) (acini, ducts and blood vessel). Based on the staining intensities measured in each ROI1 and ROI2 for each antibody, levels of fluorescence intensity and the regular organization of the staining pattern were classified as: no expression (~0–19% intensity), very weak expression (~20–39% intensity), weak expression (~40–59% intensity), expression (~60–79% intensity), and strong expression (~80–100% intensity). The highest GVI value was used as reference and all values are relative percentages of this value. In addition, DAPI staining was used to define the nuclear regions of interest (ROI3), and extracellular and nuclear staining intensities were then compared in order to provide extracellular to nuclear ratios (Noursadeghi et al., 2008). However, due to the extensive lymphocytic infiltration in NOD LGs and concomitant increase in the number of nuclei, this particular comparison may lead to overestimation of the magnitude of the changes in the NOD mouse LG. For statistical analysis, all data were displayed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies included rabbit anti-human fibrillin 1 (1:1000; (Tiedemann et al., 2001)), anti-human fibrillin 2 (1:1000) (Lin et al., 2002) and anti-human fibulin 5 (1:500) (El-Hallous et al., 2007), which extensively cross-react with mouse. Other primary antibodies used in this study include: I) polyclonal antibodies against collagen type I (R1038, 1:50; Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton/CO, USA); collagen type III (R1040, 1:50; Novus Biologicals, Inc.); collagen type IV (ab6586, 1:100; Abcam Inc., Cambridge/MA, USA); laminin 1 (ab11575, 1:50; Abcam Inc.); versican (AB1033, 1:50; Chemicon, Temecula, CA); tropoelastin (ab21601, 1:100; Abcam Inc.); MMP9 (ab38898, 1:500; Abcam Inc.); cathepsin H (sc-6497 (K-18), 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz/CA, USA) and fibronectin (A0245, 1:400; DAKO North America Inc., Carpinteria/CA, USA); as well as II) monoclonal antibodies against heparan sulphate glycosaminoglycans (ab2501, 1:100; Abcam Inc.); tenascin C (T3413, 1:200; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis/MO, USA); MMP2 (MAB3308, 1:1000; Chemicon); CD4 (YTS191.1, 1:50; Serotec Inc., Raleigh/NC, USA); and CD68 (ab53444 (FA-11), 1:100; Abcam Inc.).

Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat-anti rabbit IgG (H+L), goat-anti rat IgG (H+L), goat-anti mouse IgG (H+L), and donkey-anti goat IgG (H+L); as well as Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat-anti rat IgG (H+L) and donkey-anti goat IgG (H+L) (1:250; all from Molecular Probes, Eugene/OR, USA). To visualize the F-actin cytoskeleton, cells were stained using Alexa Fluor 594 and Alexa Fluor 647 phalloidin (1:40; Molecular Probes). For counterstaining of cell nuclei 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) was added to the final PBS washing. Staining with the corresponding IgG controls for each one of the antibodies (1:200, all from Santa Cruz), and staining without primary antibodies (background detection) served as controls.

Multiphoton imaging and second harmonic generation (SHG) signal profiling

Fresh dissected LGs of 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice were examined using the Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO femtosecond laser scanning system mounted on an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.) and coupled to a software-tunable Coherent Chameleon titanium: sapphire laser (720 nm – 930 nm, 90 MHz; Coherent Laser Group, Santa Clara/CA, USA) as described before (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). The imaging system was equipped with a high-resolution AxioCam HRc camera with 1300 × 1030 pixels (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.). Images were collected using an oil immersion Plan-Neofluar 40x/1.3 numerical aperture differential interference contrast (DIC) objective lens (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.). All observations were made using unprocessed, untreated intact tissues. Cellular and ECM structure-dependent autofluorescence, as well as SHG were induced using wavelengths of 740 nm (elastin, cells) and 860 nm (collagen). A band-pass (BP) 390–465 nm infrared-blocked filter and a short-pass (KP) 685 nm filter served as emission filters (Chroma Technology Corp, Rockingham/VT, USA). For maximum detection efficiency the pinhole was set to the maximum (1000 μm). All images were taken with a frame size of 512 × 512 pixels, with a pixel depth of 12-bit.

To quantify and compare the intrinsic fluorescence signals of collagenous structures within LG tissues of BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice, lambda stacks were ascertained at emission wavelengths of 390 nm to 470 nm (in 10 nm increments) using the two-photon Chameleon laser tuned to an excitation wavelength of 860 nm. Emission was collected using the Zeiss META detector (spectral separator) of the LSM 510 Meta NLO system as previously described (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). Signal intensities were reflected by the gray values of all the pixels within a region of interest (ROI) (gray value intensities (GVI). Mean intensities were calculated from peak intensities (ROI1) and average intensities (ROI2) of the screened ROI areas. Accordingly, all results are presented as mean values ± standard deviations.

Gene expression analysis by semi-quantitative and real-time PCR

LGs were isolated from BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice (each n=4; age: 6 and 18 weeks). Total RNA was extracted using the Versagene RNA tissue kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis/MN, USA) and treated with DNase (Versagene DNase treatment kit, Gentra Systems, Inc.) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA was generated from 2 μg of total RNA by using the Omniscript™ Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Qiagen, Valencia/CA, USA). All samples, along with the corresponding “no-RT” control (RNA) to confirm the absence of contaminating genomic DNA, were subjected to PCR (for each pair of primers n=4), carried out using 2.5 units of Taq DNA Polymerase, 10x PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, Q-solution, and specific primers (all from Qiagen). The collagen type I (Col1a1, Col1a2), type III (Col3a1) and type IV (Col4a1, Col4a2), laminin 1 (Lama1), versican (Vcan), tenascin C (Tnc), elastin (Eln), fibrillin 1 (Fbn1), fibrillin 2 (Fbn2), fibulin 5 (Fbln5), fibronectin 1 (Fn1), Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp13, Mmp14, Mmp16 and cathepsin H (Ctsh) primer sets were obtained from Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assay) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sets for RAB3D member RAS oncogene family (Rab3d, a marker that has been shown to be specific to exocrine epithelial cells such as lacrimal acinar epithelial cells, but is not expressed in inflammatory cells (da Costa et al., 2006; Schenke-Layland et al., 2008)) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) (both Qiagen) were used as “housekeeping genes”. Efficiency curves for each one of the primers tested were performed in order to check linear amplification using primers delimitating similar sized PCR products. The resultant PCR products were resolved through 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Real-time PCR and melting curve analysis (for each pair of primers) were performed using the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System, Taqman (Applied Biosystems, Foster City/CA, USA) (n=4). Primer sets utilized for real-time quantification were the same primer sets used for semi-quantitative RT-PCR, obtained from Qiagen and used following the manufacture’s instructions. PCR amplicons were detected by fluorescent detection of SYBR Green (QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit, Qiagen). Cycling conditions were as follows; 95°C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 15 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec.

Western blot analysis and densitometric evaluation

Total protein was extracted from LGs of 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice (each n=4) as described before (Marchelletta et al., 2008). The protein content was determined by a colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules/CA, USA). For Western blot analysis, equal amounts of protein (30 μg/lane) were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules/CA, USA) as described before (Schenke-Layland et al., 2004). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad/CA, USA)/0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma) buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C with the same primary antibodies used for immunohistostaining (anti-MMP2 and anti-MMP9, each diluted 1:1000). Membranes were then washed and treated with species-specific horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgGs (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly/MA, USA), and after extensive rinsing, immunoreactive protein bands were visualized by chemiluminiscence (ECL Plus Western Blotting kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway/NJ, USA). After development, membranes were stripped and re-blotted with an antibody against β-tubulin (ab6160, 1:5000; Abcam Inc.).

For semi-quantification of the protein expression levels, relative densities of the protein bands of both pro (72 kDa) and active (66 kDa) forms of MMP2, as well as pro (102–105 kDa) and active (82–88 kDa) forms of MMP9 were measured by densitometry in immunoblots and analyzed using ImageJ software as described before (Pérez-Rivero et al., 2008). The signals from the protein bands were normalized against the signal from the ‘housekeeping’ protein β-tubulin and expressed as a percentage of the control (BALB/c). In addition, the ratios of pro and active forms of MMP2 and MMP9 were calculated. All data are displayed as means ± standard deviations of results obtained in four independent experiments.

Flow cytometry

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on inflammatory cells, which were isolated from LGs of 6 and 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice (each n=5) according to a modified protocol as previously described (Guo et al., 2000). In order to identify the proportions of natural killer cells, macrophages, neutrophils and eosinophils, as well as T- and B-cells, dual-staining with the following antibodies was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated CD49b/Pan-NK; cyanine-5 (Cy5)-conjugated CD11b (Mac-1) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Gr1; PE-conjugated B220 and FITC-conjugated CD19; as well as FITC-conjugated CD4 and PE-conjugated CD8 (all 1:200; all purchased from BD Biosciences/Pharmingen, San Diego/CA, USA). Nonspecific isotype-matched Cy5-, PE- and FITC-conjugated IgGs served as controls (all BD Biosciences/Pharmingen). Staining with 7-amino-actinomycin (7-AAD; 559925; BD Pharmingen) was performed to exclude dead cells. A total of 30,000 cells were acquired for each sample. All analyses were performed using a BD LSR2 flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose/CA, USA). FCS files were exported and analyzed using FlowJo 8.3.3 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland/OR, USA).

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test or ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Histology and immunohistostaining reveal significant changes in ECM protein expression patterns in NOD LGs

No evidence of inflammation was observed within LG tissues isolated from BALB/c (Suppl. Fig. 1A and D) or the lymphocyte-deficient NOD-scid (Suppl. Fig. 1C and F) mice. In contrast, and similar to our previously reported results (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008), routine histological analysis demonstrated an infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells into the glandular parenchyma of NOD LGs, predominantly around acini and ducts, starting at the age of 6 weeks, which was further increased as the animals aged (Suppl. Fig. 1B and E).

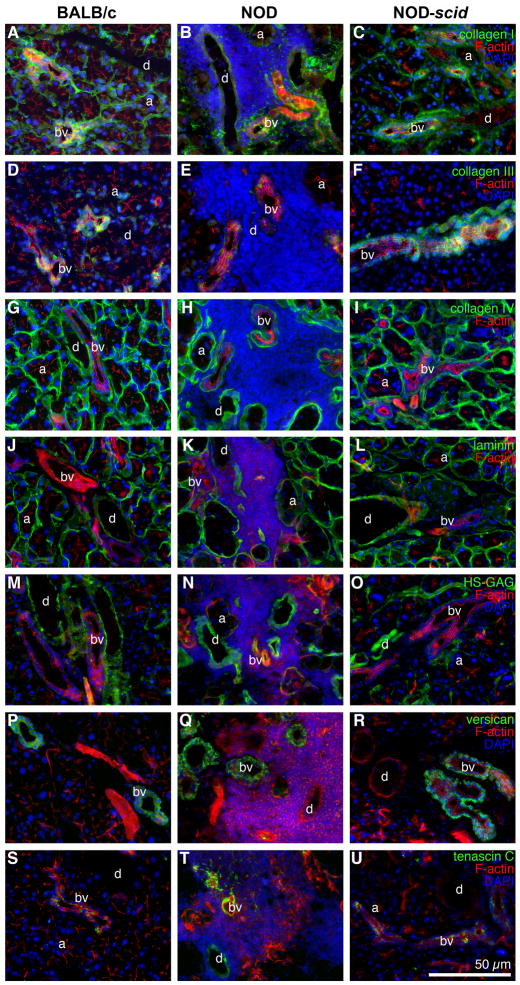

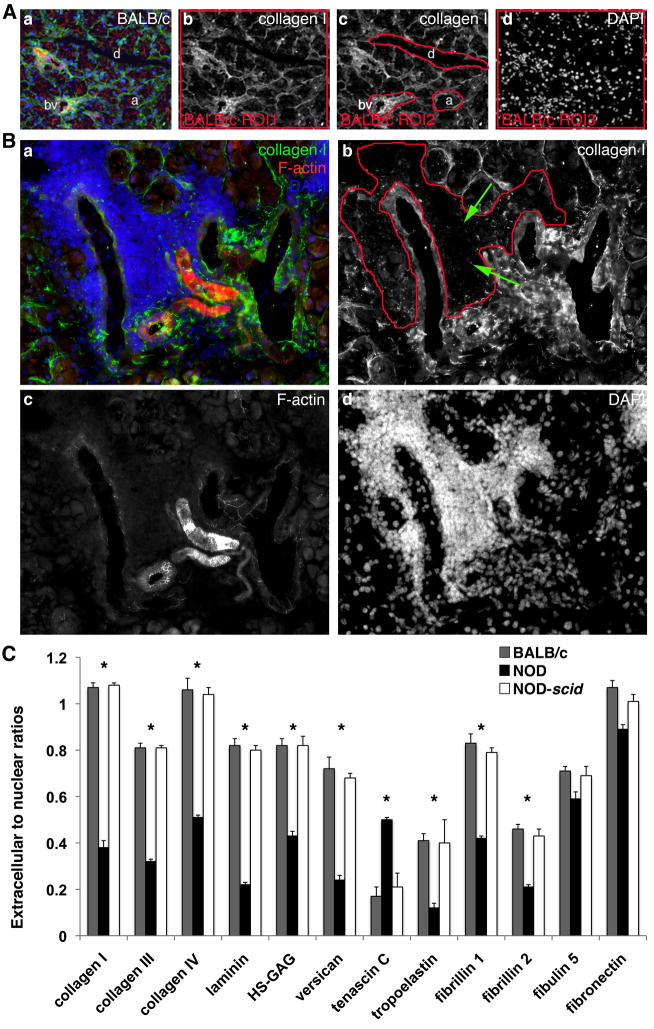

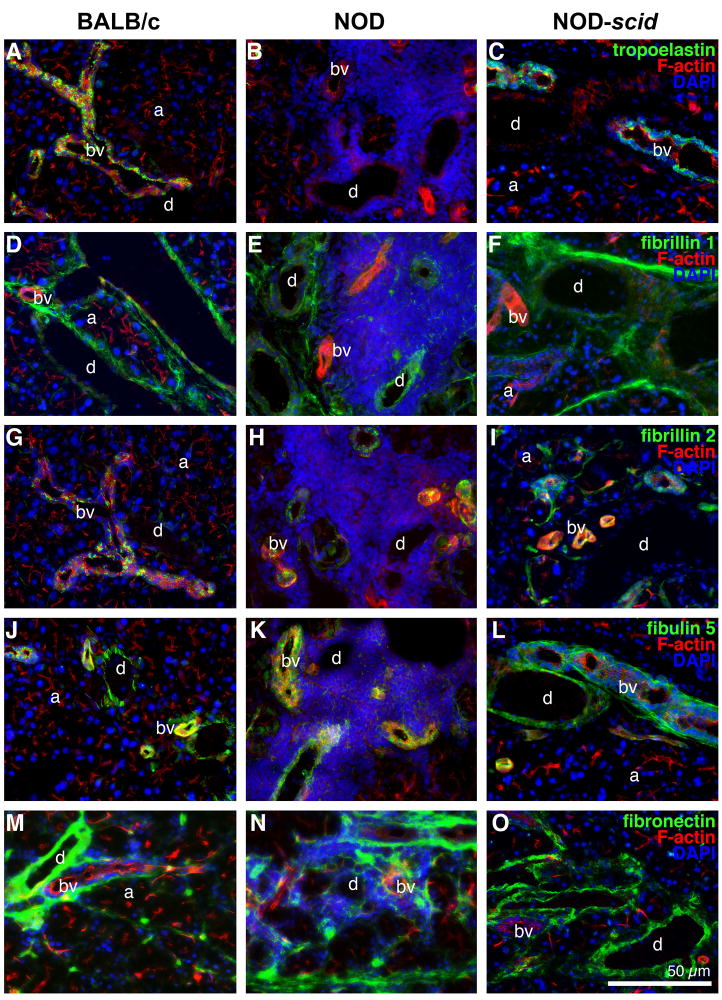

Immunofluorescence staining revealed dramatic changes of LG ECM protein patterns in NOD mice when compared to the expression patterns observed in healthy BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues (Fig. 1–3; Tables 1 and 2; Suppl. Fig. 2). Briefly, in BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues, collagen types I and IV, laminin 1, as well as heparan sulphate glycosaminoglycans (HS-GAG) were moderately to strongly expressed in the basement membranes of acini and blood vessels, and around the ducts (Fig. 1A, C; G, I; J, L; M, O; Table 1; Suppl. Fig. 2A–D and I–L). Versican, tropoelastin, fibrillin 1 and 2, as well as fibulin 5 were predominantly expressed in the basement membrane of blood vessels and around the ducts, with weak or no expression within or around the acini (Fig. 1P, R; Fig. 2A, C, D, F, G, I, J, L; Table 1). Tenascin C was weakly detectable within the blood vessels of BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (Fig. 1S and U; Table 1). Fibronectin was weakly expressed in the acini, and showed moderate to strong expression in the ducts and in the blood vessels of both BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (Fig. 2M and O; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistostaining of LGs from 18 week old BALB/c (A, D, G, J, M, P, S), NOD (B, E, H, K, N, Q, T) and NOD-scid (C, F, I, L, O, R, U) mice reveals massive inflammatory infiltrates in NOD LG tissues, mainly located around the acini (a), ducts (d) and blood vessels (bv), associated with a spatial degradation of ECM proteins. Images show F-actin staining (red) as well as positive staining (green) for: collagen type I (A–C), type III (D–F) and type IV (G–I); laminin 1 (J–L); HS-GAG (M–O); versican (P–R); and tenascin C (S–U). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bar equals 50 μm.

Fig. 3.

(A) For semi-quantitative analysis, fluorescence intensities are assessed in all tissues including BALB/c LGs (a–d). For each antibody such as collagen type I, fluorescence intensities are measured in I.) the total extracellular regions of interest (ROI1) (b; depicted by the red-outlined area), II.) the tissue structure-specific regions of interest (ROI2; acini (a), ducts (d), blood vessel (bv)) (c; depicted by the red-outlined areas), as well as III.) the nuclear regions of interest (ROI3) (d; depicted by the red-outlined area), defined using DAPI staining. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of NOD LG tissue sections reveals severe degradation of LG ECM proteins such as collagen type I (a (green) and b), predominantly found in areas that show elevated levels of inflammatory infiltrates (a (DAPI – cell nuclei staining in blue) and d), depicted by the red-outlined area in image b (please note also the green arrows). F-actin staining is shown in image a (red) and image c. (C) Graphs depict the extracellular to nuclear ratios determined using semi-quantitative immunofluorescence intensity analysis (*P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs).

Table 1.

Using identical exposure times, ECM protein expression intensities (measured as gray value intensities (GVIs)) were determined in tissue structure-specific regions of interest (ROI2) (acini, ducts and blood vessel) of BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LGs of 18 week old mice. All data are displayed as means in % ± standard deviations. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

| ECM protein | BALB/c | NOD | NODscid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acini | ducts | blood vessel | acini | ducts | blood vessel | acini | ducts | blood vessel | |

| collagen type I | 86±12 | 65±6 | 91±11 | 11±1* | 22±1* | 84±9 | 76±8 | 66±8 | 90±10 |

| collagen type III | 24±4 | 70±8 | 95±11 | 2±0.1* | 42±2* | 49±4* | 28±2 | 68±7 | 91±12 |

| collagen type IV | 98±14 | 96±10 | 72±10 | 21±1* | 90±5 | 60±7 | 95±12 | 96±9 | 72±11 |

| laminin | 91±11 | 63±10 | 45±8 | 9±0.4* | 20±6* | 40±8 | 92±13 | 67±10 | 49±5 |

| HS-GAG | 42±9 | 96±9 | 56±6 | 16±1* | 86±1 | 45±8 | 44±9 | 91±11 | 51±5 |

| versican | 4±0.4 | 25±1 | 51±8 | 3±0.1 | 20±1 | 48±4 | 3±0.3 | 26±2 | 55±8 |

| tenascin C | 9±1 | 9±2 | 33±2 | 14±2* | 64±5* | 81±12* | 8±1 | 11±2 | 30±5 |

| tropoelastin | 6±0.3 | 20±2 | 81±4 | 6±0.2 | 8±1* | 21±1* | 6±0.4 | 21±2 | 88±7 |

| fibrillin 1 | 44±5 | 97±13 | 60±3 | 26±3* | 64±5* | 38±2* | 51±5 | 98±14 | 61±6 |

| fibrillin 2 | 12±1 | 29±2 | 61±5 | 9±0.8* | 20±2* | 46±3* | 10±1 | 30±4 | 60±8 |

| fibulin 5 | 4±0.3 | 79±9 | 91±11 | 3±0.2 | 64±7 | 93±9 | 5±0.1 | 75±8 | 96±14 |

| fibronectin | 51±4 | 70±9 | 100±12 | 49±3 | 71±8 | 94±10 | 46±4 | 68±9 | 91±12 |

P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs.

Table 2.

Extracellular to nuclear ratios were calculated based on the gray value intensities (GVIs) measured in the total extracellular regions of interest (ROI1) and the nuclear regions of interest (ROI3) in BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LG tissues of 18 week old mice. All data are displayed as mean ratios ± standard deviations. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

| ECM protein | BALB/c | NOD | NODscid |

|---|---|---|---|

| collagen type I | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.03* | 1.08 ± 0.01 |

| collagen type III | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.01* | 0.81 ± 0.01 |

| collagen type IV | 1.06 ± 0.05 | 0.51 ± 0.01* | 1.04 ± 0.03 |

| laminin | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.01* | 0.80 ± 0.02 |

| HS-GAG | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.02* | 0.82 ± 0.04 |

| versican | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.02* | 0.68 ± 0.02 |

| tenascin C | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.01* | 0.21 ± 0.06 |

| tropoelastin | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.02* | 0.40 ± 0.10 |

| fibrillin 1 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.01* | 0.79 ± 0.02 |

| fibrillin 2 | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01* | 0.43 ± 0.03 |

| fibulin 5 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.04 |

| fibronectin | 1.07 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.03 |

P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs.

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence images of LG tissues from 18 week old BALB/c (A, D, G, J, M), NOD (B, E, H, K, N) and NOD-scid (C, F, I, L, O) mice showing F-actin staining (red) as well as positive staining (green) for: tropoelastin (A–C); fibrillin 1 (D–F); fibrillin 2 (G–I); fibulin 5 (J–L); and fibronectin (M–O). Cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Acini (a), ducts (d) and blood vessels (bv). Scale bar equals 50 μm.

In contrast, immunohistochemical staining of NOD LG tissue sections revealed severe degradation of LG ECM proteins, predominantly found in areas that showed elevated levels of inflammatory infiltrates (Figs. 1–3; Suppl. Fig. 2E–H); however, within the same NOD LG tissue there were both areas with intense inflammatory cell infiltration, associated with degraded ECM structures, as well as areas free of inflammatory cells in which the ECM components had a normal appearance (Fig. 1B, E, H, K, N, Q; Fig. 2B, E, H; Fig. 3B; Suppl. Fig. 2E–H). The most affected LG structures were the acini, with a significantly lower expression of collagen types I, III and IV, laminin 1, HS-GAG, as well as fibrillin 1 and 2 (Fig. 1B, E, H, K, N; Fig. 2E, H; Fig. 3B; Table 1; Suppl. Fig. 2E–H) when compared to BALB/c or NOD-scid LG structures. Significant differences in ECM protein pattern distribution were also found in the ducts, showing a weaker expression of collagen types I and III, laminin 1, tropoelastin, fibrillins 1 and 2 (Fig. 1B, E, K; Fig. 2B, E, H; Table 1; Suppl. Fig. 2E–H). A weaker expression of collagen type III, tropoelastin, fibrillins 1 and 2 was noted within blood vessels (Fig. 1E; Fig. 2B, E, H; Table 1). In addition, when focused on the extracellular to nuclear ratio (Fig. 3C; Table 2), NOD LG tissues revealed a significant decrease in ECM protein expression of collagen types I, III and IV, laminin 1, HS-GAG, versican, tropoelastin, as well as fibrillin 1 and 2. The expression of tenascin C was significantly increased in NOD LG samples when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (Fig. 1T; Tables 1 and 2). No significant differences were detectable in the expression patterns of fibulin 5 and fibronectin (Fig. 2K, N; Tables 1 and 2).

Multiphoton-induced autofluorescence imaging and SHG signal profiling display altered ECM structures in NOD LGs

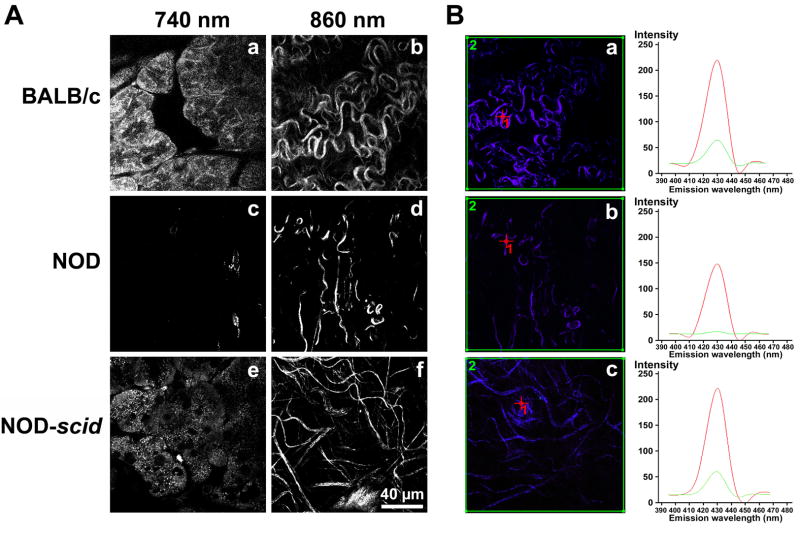

The quality of ECM structures including collagen- and elastin-containing fibers in BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LG tissues was assessed using non-invasive high-resolution multiphoton-induced autofluorescence microscopy and SHG signal profiling (Fig. 4A and B). To visualize intra-tissue LG structures via their native autofluorescence, wavelengths of 740 nm (cells and elastic fibers) and 860 nm (collagen fibers) were determined as appropriate excitation wavelengths as described previously (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008) (Fig. 4A). Exposure of fresh dissected BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs to laser pulses at 740 nm revealed predominantly cellular structures (acinar cells) within tissue depths of 20 to 30 μm (Fig. 4A; a and e). Using an excitation wavelength of 860 nm, bundles of collagen were detectable in BALB/c and NOD-scid LG specimens (Fig. 4A; b and f). In contrast, using a wavelength of 740 nm and similar laser powers as used for monitoring BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues almost no autofluorescent cellular structures or elastic fibers were detectable in NOD tissues (Fig. 4A, c). Only a few, weak, autofluorescent collagen-containing structures were visualizable at a wavelength of 840 nm (Fig. 4A, d).

Fig. 4.

(A) Multiphoton-induced autofluorescence images of fresh dissected, untreated LGs from 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid mice using two wavelengths of 740 nm (a, c, e; predominantly cells and elastic fibers) and 860 nm (b, d, e; collagen fibers). Note that within NOD LG tissues almost no cellular (c) and only reduced collagenous (d) autofluorescence are detectable. Scale bar equals 40 μm. (B) The graphs represent peak (ROI 1, red) and average (ROI 2, green) SHG intensities of collagenous structures shown in the corresponding lambda stack overlay images (BALB/c=a; NOD=b, NODscid=c), depicted by the red cross (ROI 1) or the green frame (ROI 2). Note the aberrant, very faint NOD LG SHG signal (b), indicating a substantial ultrastructural disintegration of most collagen fibers.

Diminished intrinsic fluorescence signal intensities are indicative of structural changes. That is, the weaker the autofluorescence and SHG signals are, the stronger is the evidence that major changes to ECM structures have occurred (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008; Schenke-Layland, 2008). To quantitatively evaluate these changes in SHG patterning we compared BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LG ECM structures using spectral fingerprinting (Fig. 4B). Applying this novel technique, using the same laser powers for all tissues, we were able to detect significant differences of intrinsic fluorescence signal intensity values (detected as gray value intensities (GVI)) within NOD LG tissues (Fig. 4B, b) when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (Fig. 4B, a and c). In each case, 6 different areas of each tissue sample were scanned and intensities of the SHG signals of the regions of interest (ROI) were detected. Mean intensities were calculated from peak intensities (ROI1; Fig. 4B red) as well as average intensities (ROI2; Fig. 4B green) of the screened ROI areas. Accordingly, peak SHG signal intensities of collagen structures in BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs were significantly higher (229 ± 8 GVI and 231 ± 11 GVI (ROI1; red)) when compared to NOD tissues (139 ± 18 GVI (ROI1; red)) (P<0.05). Interestingly, in regards to the average intensities within a tissue area (ROI2; green), the decrease of NOD LG SHG signal intensities was even more statistically significant when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues (31 ± 9 GVI compared to 79 ± 4 GVI and 68 ± 6 GVI; P=0.001).

Gene expression analyses reveal down-regulation of major ECM protein genes

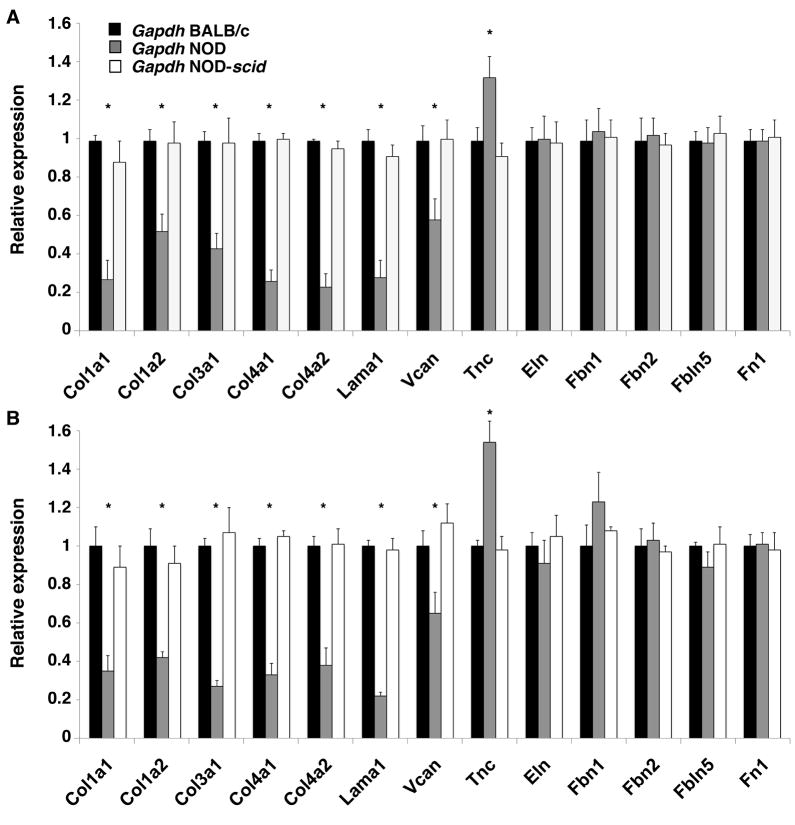

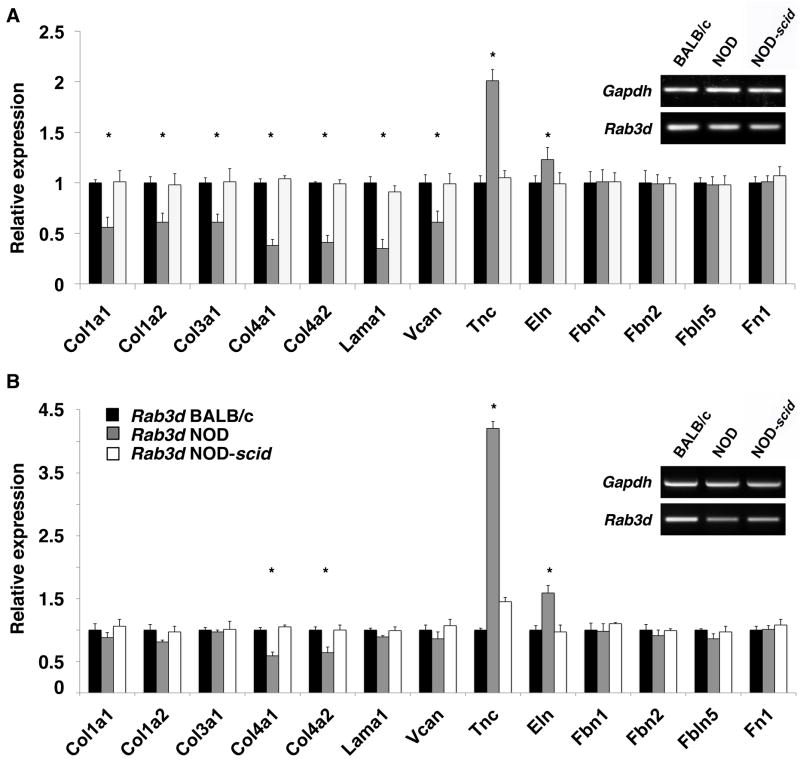

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR showed a down-regulation of collagen type I (Col1a1, Col1a2), type III (Col3a1) and type IV (Col4a1, Col1a2), laminin 1 (Lama1) and versican (Vcan) in NOD LG tissues when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (Fig. 5 and 6). Interestingly, this significantly down-regulated expression of major ECM protein genes was even more pronounced in tissues isolated from 6 week old NOD mice (Fig. 5 and 6, A), compared to LGs from 18 week old animals (Fig. 5 and 6, B). In detail, we found a significant down-regulation of collagen type I [47%–72% (normalized using Gapdh) and 44%–39% (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week and 58%–65% (normalized using Gapdh) and 12%–19% (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs]; collagen type III [53%–56% (normalized using Gapdh) and 36%–39% (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week and 62%–73% (normalized using Gapdh) and 3%–6% (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs]; collagen type IV [59%–76% (normalized using Gapdh) and 53%–69% (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week and 54%–68% (normalized using Gapdh) and 29%–38% (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs]; laminin 1 [63%–71% (normalized using Gapdh) and 59%–65% (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week and 66%-78% (normalized using Gapdh) and 9%–11% (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs]; and versican [38%–41% (normalized using Gapdh) and 23%–39% (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week and 29%–35% (normalized using Gapdh) and 10%–14% (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs] in NOD LGs when normalized with either Gapdh or Rab3d. No significant changes in the expression of elastin (Eln), fibrillin 1 (Fbn1), fibrillin 2 (Fbn2), fibulin 5 (Fbln5) or fibronectin (Fn1) were observed within 6 or 18 week old NOD LGs when normalized with Gapdh. However, when normalized with Rab3d, we found that elastin was significantly 1.23-fold (6 week LGs) and 1.59-fold (18 week LGs) up-regulated when compared to age-matched BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues. Interestingly, we further found a significant up-regulation of tenascin C (Tnc) [1.33-fold (normalized using Gapdh) to 2.01-fold (normalized using Rab3d) in 6 week LGs and 1.54-fold (normalized using Gapdh) to 4.21-fold (normalized using Rab3d) in 18 week LGs] in the NOD LG samples when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression analysis, based on normalization using Gapdh as “housekeeping gene”, of age-matched 6 (A) and 18 (B) week old NOD LGs compared to LG tissues from BALB/c and NOD-scid mice showing a significantly down-regulated expression of collagen types I, III and IV, laminin 1 and versican, as well as an increased expression of tenascin C in NOD LGs. No significant changes in fibrillin 1 and 2, fibulin 5, as well as fibronectin expression are noticed (*P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs).

Fig. 6.

Gene expression analysis of age-matched 6 (A) and 18 (B) week old NOD LGs compared to LG tissues from BALB/c and NOD-scid mice, normalizing with Rab3d (*P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs). General Rab3d gene expression patterns (semi-quantitative RT-PCR) are displayed for both 6 (A) and 18 week (B) old BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LGs. Please note that Rab3D expression varies slightly, decreasing in the NOD LGs, likely due to loss of acinar cell mass.

Inflammatory infiltration of NOD LGs is accompanied by an up-regulation of extracellular proteases that are implicated in ECM remodeling

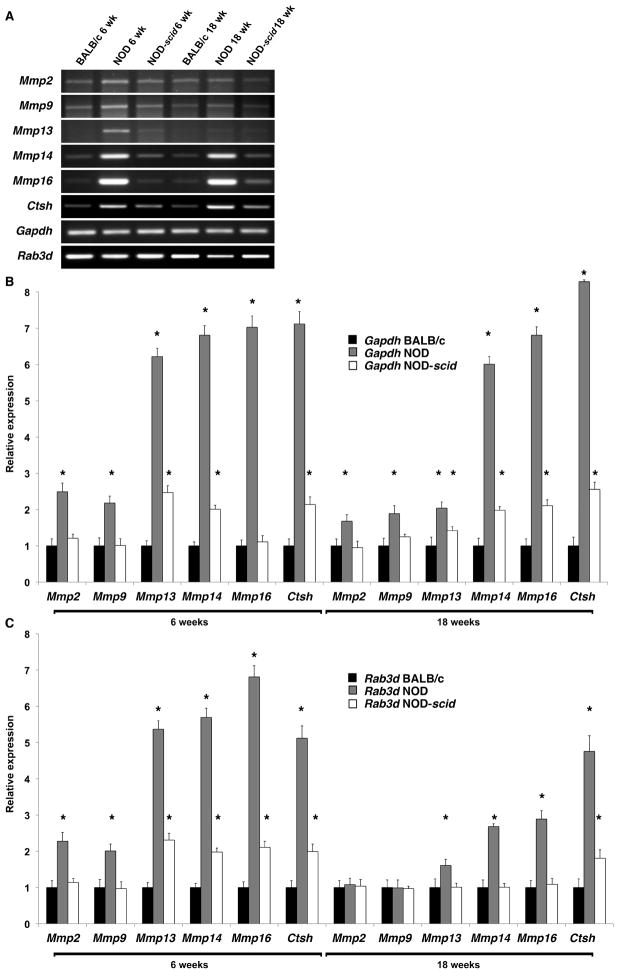

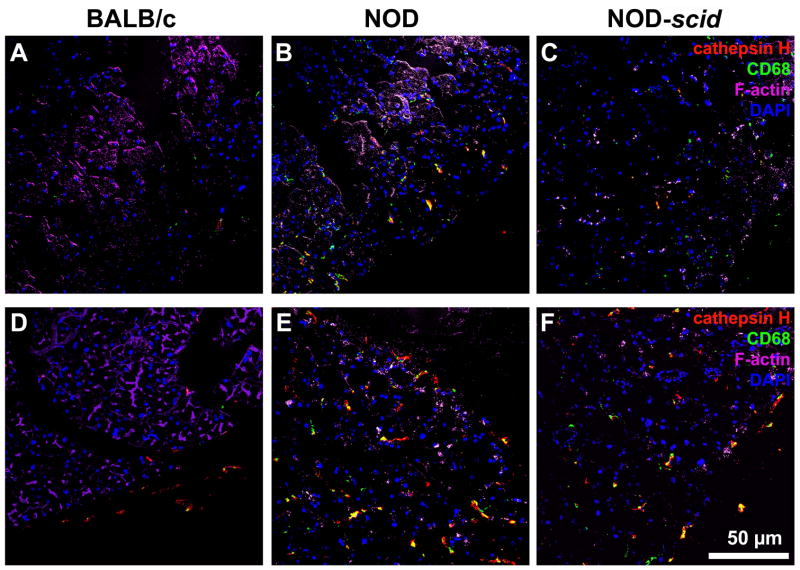

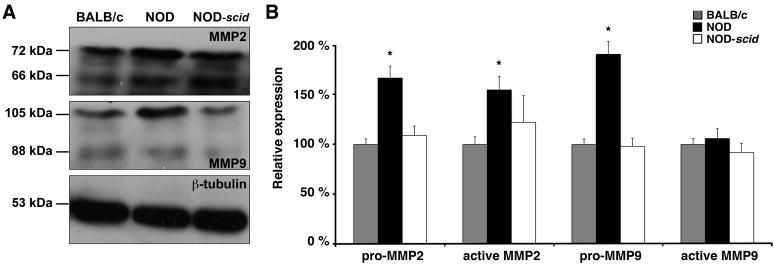

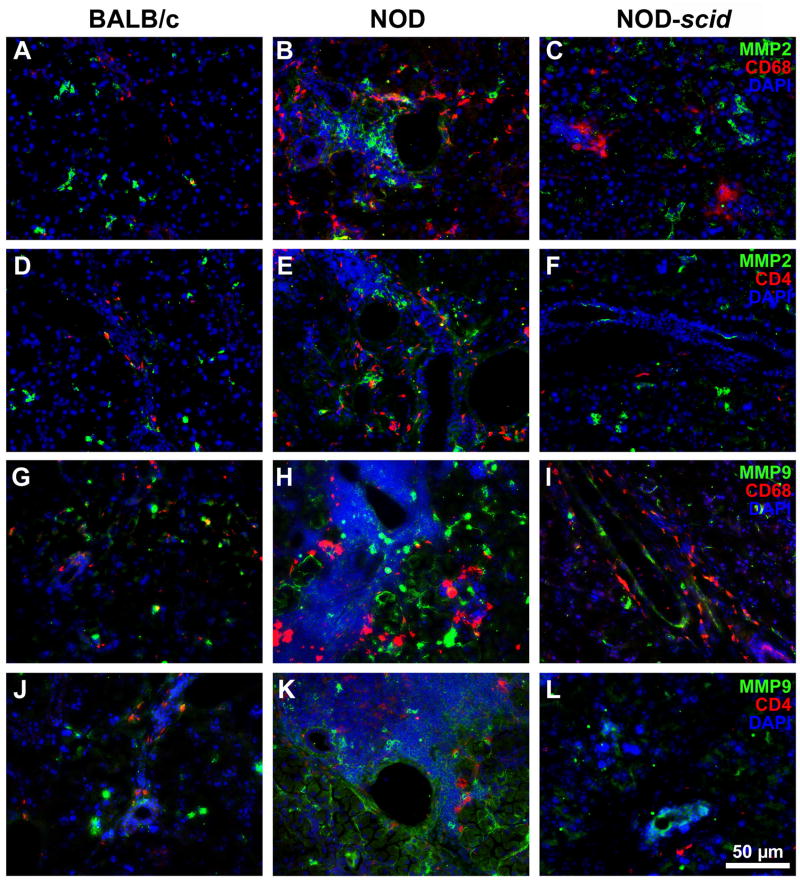

We have shown in a previous study that MMP2 and MMP9 activity levels were significantly increased in NOD LGs when compared to age-matched BALB/c LG tissues (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). In the same study we also revealed the presence of various subtypes of macrophages, neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes, as well as B- and T-cells within the inflammatory cells that infiltrate the glandular tissues of NOD mice starting by 7 weeks of age (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008). To identify if the up-regulated expression of extracellular proteases is directly related to the pathological infiltration of the NOD LGs, we performed gene and protein expression, as well as FACS analyses of LG tissues isolated from 6 and 18 week old BALB/c, NOD and immune-deficient NOD-scid mice (Figs. 7–11; Table 3; Suppl. Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Semi-quantitative and quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses demonstrated significantly up-regulated gene expression patterns of Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp13, Mmp14, Mmp16, and most notably Ctsh in NOD LG tissues isolated from 6 and 18 week old mice (Fig. 7A–C). Semi-quantitative Western blot analysis revealed an elevated level of active MMP9 (106 ± 10%) and a significantly increased expression of both pro (167 ± 12%) and active (155 ± 14%) forms of MMP2, as well as pro-MMP9 (191 ± 13%) in NOD LG samples when compared to either BALB/c controls, which are represented as 100% on the displayed graphs, or NOD-scid LG tissues (pro-MMP2: 109 ± 10%; active MMP2: 139 ± 19%; pro-MMP9: 99 ± 8%; active MMP9: 92 ± 9%) (Fig. 8A and B). Further analysis showed that the ratio of pro versus active forms of MMP2 was lower compared to a higher ratio of pro versus active MMP9 in the NOD LG tissues (ratio pro/active MMP2: 1.07 compared to ratio pro/active MMP9: 1.80) (Fig. 8B), suggesting that MMP9 is overall more up-regulated in the NOD tissues when compared to MMP2. Immunohistostaining showed a strong expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in areas of infiltration in NOD LG tissues obtained from 18 week old mice, predominantly located around the inflammatory cells including macrophages, their precursors and T-lymphocytes that were identified using antibodies against CD4 and CD68 (Figs. 9 and 10; Suppl. Fig. 3; white arrows). However, we also found areas with elevated levels of MMP2 and MMP9 that were not co-localized with CD68-expressing macrophages or CD4-expressing T-lymphocytes (Suppl. Fig. 3B, D, F, H; blue arrows). Staining of the non-infiltrated BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs showed only weak expression of MMP2 and MMP9 (Fig. 10A, D, G, J and C, F, I, L). Immunofluorescence co-staining for cathepsin H and CD68 showed similarly low expression patterns in BALB/c LG tissues (Fig. 10A and D). In contrast, an increase in cathepsin H immunoreactivity was detectable starting by 6 weeks in NOD as well as NOD-scid mouse LGs (data not shown), consistent with the PCR data presented in Fig. 7. Interestingly, these increased levels of cathepsin H were sustained in both the 18 week old NOD and NOD-scid specimens, co-localized with CD68-positive tissue macrophages (Fig. 11B, E and C, F).

Fig. 7.

(A) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR demonstrates an up-regulated expression of Mmp2, Mmp9, Mmp13, Mmp14, Mmp16 and Ctsh in 6 and 18 week old NOD LGs when compared to age-matched BALB/c and NOD-scid LG tissues. (B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis, with normalization using Gapdh, confirmed the semi-quantitative PCR results (*P<0.05 versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs). (C) Data obtained using real-time RT-PCR analysis with normalization using Rab3d.

Fig. 11.

Immunohistostaining of 6 (A–C) and 18 (D–F) week old BALB/c (A, D), NOD (B, E), and NOD-scid (C, F) LG tissues depicting increased levels of cathepsin H (red) predominantly seen in the 18 week old NOD and NOD-scid specimens (E and F), co-localized with CD68-positive tissue macrophages in green. Cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar equals 50 μm.

Table 3.

FACS analysis of BALB/c, NOD and NOD-scid LG tissues.

| Age | 6 weeks | 18 weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | BALB/c | NOD | NODscid | BALB/c | NOD | NODscid |

| B220+ CD19- | 6.8% | 3.4% | 6.9% | 6.7% | 4.2% | 7.4% |

| B220+ CD19+ | 4.1% | 24.0% | 0.8% | 4.2% | 52.9% | 1.0% |

| CD4+ CD8- | 2.6% | 12.9% | 2.0% | 3.7% | 14.1% | 4.9% |

| CD4- CD8+ | 1.9% | 7.6% | 1.1% | 2.4% | 8.0% | 2.3% |

| CD49b/Pan-NK | 3.2% | 4.5% | 1.4% | 4.0% | 8.7% | 4.7% |

| CD11b+ GR1- | 7.4% | 16.4% | 10.1% | 8.0% | 36.5% | 19.9% |

| CD11b+ GR1+ | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.1% | 2.4% | 4.7% | 1.8% |

| CD11b- GR1+ | 4.2% | 7.3% | 2.5% | 4.1% | 6.5% | 4.4% |

Fig. 8.

(A) Representative Western blots showing an up-regulated expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in 18 week old NOD LG tissues when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs. (B) Semi-quantitative densitometric analysis reveals a significant increase of pro and active MMP2 and MMP9 in NOD LGs when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (*P<0.05). Values are expressed as percentage of BALB/c controls.

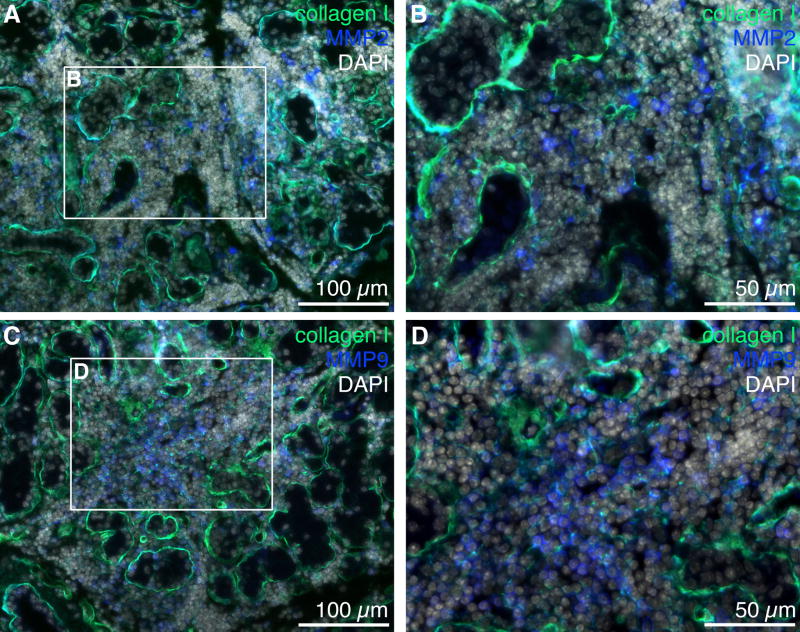

Fig. 9.

Immunofluorescence staining of NOD LG tissues obtained from 18 week old mice revealing a strong expression of MMP2 (A, B; blue) and MMP9 (C, D; blue) in infiltrated areas that reveal a reduced expression of ECM proteins such as collagen type I (A–D; green). Cell nuclei (DAPI) are shown in white. Scale bars equal 100 μm (A, C) and 50 μm (B, D).

Fig. 10.

Immunofluorescence staining shows an up-regulation of MMP2 (green; A–F) and MMP9 (green; G–L) in areas of inflammation in 18 week old NOD LG tissues versus BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs (B, E, H, K versus A, D, G, J and C, F, I, L). Images reveal the presence of tissue macrophages (CD68; A-C and G–I) and T-lymphocytes (CD4; D–F and J–L) in red, as well as cell nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar equals 50 μm.

To verify the presence of leukocytes in the NOD LGs and to further identify their role in the degradation of critical LG ECM structures, FACS analyses were performed. We found an infiltration of lymphocytes (B-cells, T-cells, natural killer (NK) cells), macrophages, as well as neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes in the LGs of NOD mice as early as 6 weeks of age (Table 3; Suppl. Fig. 4). Interestingly, the infiltration of these cells became much more pronounced by age, and at 18 weeks of age, FACS analysis revealed a massive infiltration of B220+ CD19+ expressing B-cells (52.9%), CD4+ CD8− mature T helper cells (14.1%), CD4− CD8+ mature cytotoxic T-cells (8%), CD49b+/Pan-NK expressing NK cells (8.7%), macrophages (CD11b+ GR1−; 36.5%), CD11b+ GR1+ myeloid immunoregulatory cells (4.7%), and 6.5% of the inflammatory cells were of granulocytic origin (CD11b− GR1+), pointing towards a very severe inflammatory response in the LGs of NOD mice (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008) (Table 3; Suppl. Fig. 5). Intriguingly, this was in great contrast to cells isolated from BALB/c LG tissues, which displayed only low numbers of inflammatory cells in both LGs of 6 and 18 week old animals (Table 3; Suppl. Figs. 4 and 5). As expected, cells isolated from LGs of NOD-scid mice, which are NOD mice lacking the scid gene making them severely immunocompromised (Robinson et al., 1997), displayed significantly lower numbers of B- and T-cells, NK cells as well as macrophages and granulocytes when compared to NOD LGs. More importantly, NOD-scid mice, as well as BALB/c mice, exhibited normal LG ECM structures, indicating that the inflammatory cells, especially the lymphocytes seen in the LGs of NOD mice, are responsible for the degradation of the LG ECM (Table 3; Suppl. Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

In our previous study, we provided a detailed analysis of the LG matrix structure in combination with a qualitative matrix protein evaluation (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008), representing the first comprehensive identification and characterization of the composition of LG ECM. Using routine histology, biochemistry, immunohistochemistry and gene expression analyses, in combination with novel multiphoton imaging we could demonstrate that healthy murine LGs are composed of collagen types I, III, and IV; elastin and tropoelastin; fibronectin; laminin 1 as well as tenascin C, HS-GAG and decorin; and that an increased degradation of most of these LG ECM structures is associated with the pathogenesis of SjS detected in the NOD mouse model, representing a key event as the disease progresses. We could further reveal the presence of inflammatory cells, including various subtypes of macrophages, neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes, as well as B- and T-cells that infiltrate the glandular tissues of the mice starting by 6 weeks of age, and detected a significant increase in MMP2 and MMP9 expression, particularly appearing in areas of inflammation. However, the initial events that contribute to this increased protease activity, which ultimately results in LG matrix degradation and loss of LG function, were not clearly determined.

In this study we sought to identify the initial mechanistic events responsible for LG ECM degradation, using LG tissues of NOD-scid mice, as it had been suggested by previous reports on SG tissues (Yamachika et al., 1998). Routine histological analysis showed, in contrast to BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues, an infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells into the glandular parenchyma of NOD LGs, starting as early as 6 weeks of age, which further increased as the animals aged. Similar to the results described in our previous study (Schenke-Layland et al., 2008), immunohistochemistry, gene expression analysis and multiphoton imaging revealed dramatic changes in general LG ECM protein patterns and the three-dimensional LG matrix structure in NOD mice when compared to both, healthy BALB/c and NOD-scid tissues. BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs showed expression of collagen types I, III, and IV; elastin and tropoelastin; fibrillin 1 and 2; laminin 1 as well as HS-GAG and versican. The expression of these ECM proteins was significantly decreased in NOD LGs. Interestingly, no differences in the expression patterns of fibulin 5 and fibronectin were detectable, and, in contrary, the expression of tenascin C was significantly increased in the NOD LG samples when compared to BALB/c and NOD-scid LGs. As determined by multiphoton-induced autofluorescence and SHG microscopy, diminished intrinsic fluorescence signal intensities were additionally indicative of structural changes in NOD LGs.

SjS is one of the three most common chronic autoimmune disorders (Pillemer et al., 2001). Despite extensive molecular, histological and clinical studies, the underlying cause(s) of SjS and the etiology of the loss of secretory function remains largely unknown. It has been previously reported that glandular destruction in SjS is mainly mediated by CD4-expressing T lymphocytes; however, an impaired secretory function of salivary and lacrimal glands in SjS patients appears already in the initial phase of the inflammatory infiltration (Xanthou et al., 1999; Garcia-Carrasco et al., 2006). Interestingly, our data confirm these observations, showing that the significantly down-regulated expression of major ECM protein genes was even more pronounced in tissues isolated from 6 week old NOD mice, when compared to LGs from 18 week old animals, suggesting that the process of ECM degradation is closely coupled to the onset of the disease. The important role of extracellular matrix in modulating lacrimal acinar secretory responses has been established in a number of studies (Chen et al. 1998; Laurie et al., 1996; Andersson et al., 2006), so it is perhaps unsurprising that disruption of these interactions might rapidly be accompanied by functional quiescence.

Moreover, to verify the presence of leukocytes in the NOD LGs and to further identify their role in the degradation of critical LG ECM structures and therefore in the progression of the LG exocrinopathy, we performed for the first time comprehensive FACS, gene and protein expression analyses. Combining these advanced techniques, we revealed that the inflammatory infiltration of NOD LGs, predominantly consisting of lymphocytes, was accompanied by an up-regulation of extracellular proteases that are implicated in ECM remodeling, including MMP2, MMP9, MMP13, MMP14, MMP16 and cathepsin H. Most notably, healthy BALB/c mice, as well as the severely immunocompromised NOD-scid mice, which displayed, as expected, significantly lower numbers of B-, T- and NK cells, as well as macrophages and granulocytes when compared to NOD LGs, exhibited normal LG ECM structures. Based on what is known of protease expression and function (Goetzl et al., 1996; Leppert et al., 2001; Garcia-Carrasco et al., 2006; Cauwe et al., 2007), our findings strongly suggest that the up-regulated expression of extracellular proteases is highly correlated with the pathologic lymphocytic infiltration of the NOD LGs.

We have presented data that support our hypothesis that the infiltrating immune cells are largely responsible for the enhanced protease expression and ECM degradation in the NOD mouse LG. Still, we note that NOD mouse LG also exhibit fundamentally reduced levels of collagen and laminin gene expression. An additional possibility for the observed decrease in fidelity of ECM in the NOD mouse LG would be that these LG lack the essential ECM components to maintain cellular homeostasis, so this change then attracts the infiltrates which then worsen the observed ECM degradation and pathology.

One of the major challenges in the treatment of autoimmune dacryoadenitis of the LGs associated with SjS has been the lack of a clear relationship between the extent of lymphocytic infiltration of the LGs and the impact on tear production and release. Simply treating the infiltration may be insufficient to restore normal function to the LGs, given the significant alterations in ECM architecture and cytokine signaling. Recent work has suggested that the ensuing changes in cytokine expression profiles associated with lymphocytic foci can significantly affect the signaling environment within acini, as well as affect the release of neurotransmitters from innervating neurons, thus sustaining the immediate effects of inflammation (Zoukhri, 2005). We suggest that, in addition to simply enhancing the migration of lymphocytes into the tissue, ECM degradation may play a sustained role in altering the acinar signaling environment. In addition, a significant degradation of the tissue ultrastructure may disrupt the signaling scaffolds within the cell, as it has been shown in other tissues (Kim et al., 2000). If additional studies of LGs from other disease models or human SjS patients reveal evidence for ECM destruction as an early event in disease development similar to the changes reported here, MMP inhibitor therapies in combination with immunomodulatory regimens may serve as new treatments for SjS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yekaterina Butylkova for her excellent technical assistance, and Dr. Ali Nsair for his helpful comments. This work was supported by the NIH (5T32HL007895-10 to K.S-L.; EY-11386 to S.H-A.) and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-68836 to D.P.R.).

Abbreviations

- SjS

Sjögren’s syndrome

- LG(s)

lacrimal gland(s)

- SG(s)

salivary gland(s)

- NOD

non-obese diabetic

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- MMP(s)

matrix metalloproteinase(s)

- scid

severe combined immune deficiency

- HS-GAG

heparan sulphate glycosaminoglycans

- DAPI

4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- SHG

second harmonic generation

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- BP

band-pass

- KP

short-pass

- ROI

region of interest

- GVI

gray value intensities

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- Cy5

cyanine-5

- PE

phycoerythrin

- 7AAD

7-amino-actinomycin

- NK cells

natural killer cells

- RT

reverse transcription

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ROI

region of interest

- CD4

cluster of differentiation 4

- CD8

cluster of differentiation 8

- CD68

cluster of differentiation 68

- CD49b/Pan-NK

cluster of differentiation 49b

- B220

cluster of differentiation 45R (CD45R)

- CD19

cluster of differentiation 19

- GR1

granulocyte-differentiation antigen-1

- CD11b (Mac-1)

cluster of differentiation 11b or Integrin alpha M or macrophage-1 antigen

- Col1a1

collagen type I alpha 1

- Col1a2

collagen type I alpha 2

- Col3a1

collagen type III alpha 1

- Col4a1

collagen type IV alpha 1

- Col4a2

collagen type IV alpha 2

- Lama1

laminin 1

- Vcan

versican

- Tnc

tenascin C

- Eln

elastin

- Fbn1

fibrillin 1

- Fbn2

fibrillin 2

- Fbln5

fibulin 5

- Fn1

fibronectin 1

- Ctsh

cathepsin H

- Gapdh

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Rab3d

RAB3D member RAS oncogene family.

Footnotes

All abbreviations for mouse genes are as designated in the NCBI database with the first letter capitalized and the rest of the letters in lower case.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersson SV, Hamm-Alvarez SF, Gierow JP. Integrin adhesion in regulation of lacrimal gland acinar cell secretion. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(3):543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabino S, Dana MR. Animal models of dry eye: a critical assessment of opportunities and limitations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(6):1641–1646. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauwe B, van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G. The biochemical, biological, and pathological kaleidoscope of cell surface substrats processed by matrix metalloproteinases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42(3):113–185. doi: 10.1080/10409230701340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa SR, Wu K, Pidgeon M, Ding C, Schechter JE, Hamm-Alvarez SF. Male NOD mouse external lacrimal glands exhibit profound changes in the exocytotic pathway early in postnatal development. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cuadra-Blanco C, Peces-Peña MD, Jáñez-Escalada L, Mérida-Velasco JR. Morphogenesis of the human excretory lacrimal system. J Anat. 2006;209(2):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Glass JD, Walton SC, Laurie GW. Role of laminin-1, collagen IV, and an autocrine factor(s) in regulated secretion by lacrimal acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(1 Pt1):C278–C284. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hallous E, Sasaki T, Hubmacher D, Getie M, Tiedemann K, Brinckmann J, Bätge B, Davis EC, Reinhardt DP. Fibrillin-1 interactions with fibulins depend on the first hybrid domain and provide an adaptor function to tropoelastin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(12):8935–8946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI, Adamson TC, 3rd, Fong S, Robinson CA, Morgan EL, Robb JA, Howell FV. Lymphocyte phenotype and function of pseudolymphoma associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:52–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI110984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI, Robinson CA, Curd J, Kozin F, Howell FV. Sjögren’s syndrome: proposed criteria for classification. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:577–585. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carrasco M, Fuentes-Alexandro S, Escarcega RO, Salgado G, Riebeling C, Cervera R. Pathophysiology of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:921–932. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicovich E, Molina C, Perez P, Aguilera S, Fernandez J, Olea N, Alliende C, Leyton C, Romo R, Leyton L, Gonzalez MJ. Enhanced degradation of proteins of the basal lamina and stroma by matrix metalloproteinases from the salivary glands of Sjogren’s syndrome patients: correlation with reduced structural integrity of acini and ducts. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;48(9):2574–2584. doi: 10.1002/art.11178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Banda MJ, Leppert D. Matrix metalloproteinases in immunity. J Immunol. 1996;156:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Azzarolo AM, Schechter JE, Warren DW, Wood RL, Mircheff AK, Kaslow HR. Lacrimal gland epithelial cells stimulate proliferation in autologous lymphocyte preparations. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:11–22. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys-Beher MG, Peck AB. New concepts for the development of autoimmune exocrinopathy derived from studies with the NOD mouse model. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44(Suppl 1):S21–25. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Parry EJ, Watson RE, Garrod DR, Griffiths CE. All-trans retinoic acid compromises desmosome expression in human epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(4):577–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HE, Dalal SS, Young E, Legato MJ, Weisfeldt ML, D’Armiento J. Disruption of the myocardial extracellular matrix leads to cardiac dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(7):857–866. doi: 10.1172/JCI8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Robinson CP, Peck AB, Vela-Roch N, Sakata KM, Dang H, Talal N, Humphreys-Beher MG. Inappropriate apoptosis of salivary and lacrimal gland epithelium of immunodeficient NOD-scid mice. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16(6):675–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie GW, Glass JD, Ogle RA, Stone CM, Sluss JR, Chen L. “BM180”: a novel basement membrane protein with a role in stimulus-secretion coupling by lacrimal acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(6 Pt1):C1743–C1750. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.6.C1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert D, Lindberg RLP, Kappos L, Leib SL. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional effectors of inflammation in multiple sclerosis and bacterial meningitis. Brain Res Rev. 2001;36(2–3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Tiedemann K, Vollbrandt T, Peters H, Bätge B, Brinckmann J, Reinhardt DP. Homo- and heterotypic fibrillin-1 and -2 interactions constitute the basis for the assembly of microfibrils. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50795–50804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchelletta RR, Jacobs DT, Schechter JE, Cheney RE, Hamm-Alvarez SF. The Class V Myosin Motor, Myosin 5c, Localizes to Mature Secretory Vesicles and Facilitates Exocytosis in Lacrimal Acini. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C13–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00330.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto I, Tsubota K, Satake Y, Kita Y, Matsumura R, Murata H, Namekawa T, Nishioka K, Iwamoto I, Saitoh Y, Sumida T. Common T Cell Receptor Clonotype in Lacrimal Glands and Labial Salivary Glands from Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(8):1969–1977. doi: 10.1172/JCI118629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina C, Alliende C, Aguilera S, Kwon YJ, Leyton L, Martinez B, Leyton C, Perez P, Gonzalez MJ. Basal lamina disorganization of the acini and ducts of labial salivary glands from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: association with mononuclear cell infiltration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:178–183. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noursadeghi M, Tsang J, Haustein T, Miller RF, Chain BM, Katz DR. Quantitative imaging assay for NF-kappaB nuclear translocation in primary human macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329(1–2):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel VN, Rebustini IT, Hoffman MP. Salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Differentiation. 2006;74(7):349–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer SR, Matteson EL, Jacobsson LT, Martens PB, Melton LJ, 3rd, O’Fallon WM, Fox PC. Incidence of physician-diagnosed primary Sjogren syndrome in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:593–599. doi: 10.4065/76.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez P, Goicovich E, Alliende C, Aguilera S, Leyton C, Molina C, Pinto R, Romo R, Martinez B, Gonzalez MJ. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases in labial salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren’s symdrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(12):2807–2817. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2807::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rivero G, Ruiz-Torres MP, Díez-Marqués ML, Canela A, López-Novoa JM, Rodríguez-Puyol M, Blasco MA, Rodríguez-Puyol D. Telomerase deficiency promotes oxidative stress by reducing catalase activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(9):1243–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CP, Yamachika S, Alford CE, Cooper C, Pichardo EL, Shah N, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Elevated levels of cysteine protease activity in saliva and salivary glands of the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model for Sjögren syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5767–5771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa K, Ishimaru N, Yanagi K, Arakaki R, Ogawa K, Saito I, Katunuma N, Hayashi Y. Cathepsin S inhibitor prevents autoantigen presentation and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(3):361–369. doi: 10.1172/JCI14682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenke-Layland K, Riemann I, Opitz F, König K, Halbhuber KJ, Stock UA. Comparative Study of Cellular and Extracellular Matrix Composition of Native and Tissue Engineered Heart Valves. Matrix Biology. 2004;23:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenke-Layland K, Xie J, Angelis E, Wu K, Riemann I, Starcher B, MacLellan WR, Hamm-Alvarez SF. Increased degradation of extracellular matrix structures of lacrimal glands implicated in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Matrix Biology. 2008;27:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenke-Layland K. Non-invasive multiphoton imaging of extracellular matrix structures. J Biophoton. 2008;6:451–462. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200810045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaishi H, Kimura T, Dalal S, Okada Y, D’Armiento J. Joint diseases and matrix metalloproteinases: a role for MMP-13. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9(1):47–54. doi: 10.2174/138920108783497659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HA, Spooner BS. Proteoglycan and glycosaminoglycan synthesis in embryonic mouse salivary glands: effects of beta-D-xyloside, an inhibitor of branching morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1983;96(5):1443–1450. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann K, Bätge B, Müller PK, Reinhardt DP. Interactions of fibrillin-1 with heparin/heparan sulfate, implications for microfibrillar assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;38:36035–36042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota K, Xu K, Fujihara T, Katagiri S, Takeuchi T. Decreased reflex tearing is associated with lymphocytic infiltration in lacrimal glands. J Rheumatology. 1996;23:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blokland SC, Versnel MA. Pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome: characteristics of different mouse models for autoimmune exocrinopathy. Clin Immunol. 2002;103(2):111–124. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blokland SC, Van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, Wierenga-Wolf AF, Tielemans D, Drexhage HA, Van De Merwe JP, Homo-Delarche F, Versnel MA. Apoptosis and apoptosis-related molecules in the submandibular gland of the nonobese diabetic mouse model for Sjogren’s syndrome: limited role for apoptosis in the development of sialoadenitis. Lab Invest. 2003;83(1):3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000048721.21475.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthou G, Tapinos NI, Polihronis M, Nezis IP, Margaritis LH, Moutsopoulos HM. CD4 cytotoxic and dendritic cells in the immunopathologic lesion of Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:154–163. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, March L, Sambrook PN, Jackson CJ. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 by activated protein C: relevance to inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2864–2874. doi: 10.1002/art.22844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamachika S, Nanni JM, Nguyen KH, Garces L, Lowry MM, Robinson CP, Brayer J, Oxford GE, da Silveira A, Kerr M, Peck AB. Excessive synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases in exocrine tissues of NOD mouse models for Sjogren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(12):2371–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamachika S, Brayer J, Oxford GE, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Aberrant proteolytic digestion of biglycan and decorin by saliva and exocrine gland lysates from the NOD mouse model for autoimmune exocrinopathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(2):233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoukhri D. Effect of inflammation on lacrimal gland function. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82(5):885–898. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.