Abstract

The level of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) profoundly influences essential cell behaviors such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration. The spatial and temporal pattern of BMP2 synthesis, particular in diverse embryonic cells, is highly varied and dynamic. We have identified GC-rich sequences within the BMP2 promoter region that strongly repress gene expression. These elements block the activity of a highly conserved, osteoblast enhancer in response to FGF2 treatment. Both positive and negative gene regulatory elements control BMP2 synthesis. Detecting and mapping the repressive motifs is essential because they impede the identification of developmentally regulated enhancers necessary for normal BMP2 patterns and concentration.

Keywords: Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), gene regulation, transgenic mice, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF2), osteoblast, enhancer

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) belong to the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) superfamily and play critical roles in developmental processes [1]. BMPs were first identified and their genes were cloned due to their ability to initiate the osteogenic cascade [2; 3; 4]. Subsequent studies showed that BMPs were expressed in various embryonic structures. Bmp2 (BMP2A), a founding member of the BMP family, is expressed in the mesenchymal condensations giving rise to bones and teeth [5; 6]. BMP2, one of the first growth factors induced following bone fracture ([7] and refs. therein), has proved to be indispensable for fracture repair [8]. Loss of BMP2 function in mouse is lethal during early embryogenesis [9], proving that BMP signaling is essential for many embryonic processes.

The sequences of BMPs proteins have been remarkably conserved during evolution. BMP genes from distantly related phyla (e.g. arthropods, mollusks, cnidarians, and nematodes) have been cloned. Except for the nematode BMPs, the amino acid sequences of nonvertebrate BMPs and human BMP2 share 70 to 87% identity ([10] and refs. therein). The Drosophila protein DPP is 71% identical to human BMP2. In addition, the functions of the BMP proteins are strikingly conserved. For example, the Drosophila BMP2 homolog, DPP, induces bone in a mammalian bone induction assay [11]. Indeed, the entire BMP signaling pathway is conserved between vertebrates and invertebrates [12]. The high conservation of the BMP2 gene and its crucial roles in development, suggest that BMP2 gene regulation would be extremely tightly regulated.

The vitamin A-derivative retinoic acid (RA) strongly induces BMP2 expression in F9 embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells [13; 14; 15] and other cell types such as developing chick limb cells [16], medulloblastoma cells [17] and P19 mouse EC cells [18]. Mycoplasma infection also is a potent BMP2 inducer in diverse cell types [19]. In addition, the BMP2 protein itself stimulates BMP2 expression [20]. Other agents include estrogen [21], statins [22], NF-κB [23], the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α [24; 25], and bisphosphonates [26]. Finally, stage-dependent, reciprocal regulation of BMP2 and FGF2 in osteoblasts influences osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo [27; 28; 29].

Numerous highly conserved antagonists such as Noggin repress the action of BMP2 at the extracellular level [30; 31]. Repressors can block every intracellular signaling transduction step [32; 33]. Negative post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms also may influence BMP2 expression [34; 35]. A growing body of evidence indicates that relief of repression at multiple regulatory levels is an important means of controlling BMP2 gene expression.

We previously identified repressive transcriptional mechanisms involving Sp1 and retinoic acid receptor (RAR)β. In undifferentiated mouse F9 embryonal carcinoma cells that do not transcribe the Bmp2 gene, non-retinoid bound RARβ and Sp1 proteins assemble on the inactive promoter and disassemble after retinoids induce Bmp2 expression and differentiation [36]. The stoichiometry of Sp1, often an activator, and Sp3, often a repressor, on the same GC-rich region of the Bmp2 promoter differs between undifferentiated and differentiated cells [37]. Thus, competition between these ubiquitous factors influences Bmp2 transcription. Both the distal and proximal Bmp2 promoters are highly GC-rich. GC-rich cis-regulatory elements and the many ubiquitous activators and repressors such as Sp1 and Sp3 that bind them have been shown to regulate many essential genes [38; 39]. Enhancers that would activate transcription from GC-rich promoters must overcome the generally repressive nature of GC binding factors such as Sp3 [38].

Previous studies had demonstrated that a 1.7 kb sequence flanking the distal mouse Bmp2 promoter drove reporter gene expression in the same pattern as the endogenous Bmp2 mRNA in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells differentiated into primitive or parietal endoderm [40]. In contrast, larger sequences failed to be induced during differentiation and, in some cases, were less active than the control plasmid driven by the minimal Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) promoter [40]. We have now mapped powerful repressor elements in the promoter region of the mouse and human BMP2 genes.

Materials And Methods

Cell culture

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine without antibiotics. MC3T3-E1 cells were grown in non-ascorbic acid-containing α-MEM (Invitrogen #01-0083D) with 2 mM glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37° C. Cells were transfected using FuGene6 Transfection Reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. After transfection, cells were lysed with 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and luciferase activities were measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Human BMP2 promoter reporter gene constructs

All positions are indicated according to the distal start site of the human BMP2 gene [15].

Construct A (nt - 4752 to 906, pGL3 2198) and construct B (nt -95 to 906, pGL3 2185) were kindly provided by Dr. S. Harris at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX [41].

Construct C (nt - 246 to 906, pGL3 hB2PvNc). A PvuII and NcoI fragment containing the 921 nt human BMP2 promoter was excised from construct A and was ligated with the 4,860 nt SmaI and NcoI fragment in the pGL3 basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI).

Construct D (nt -147 to 906, pGL2 h822). A fragment containing -147 nt to 906 nt was generated by PCR using primers 5′ CGTCCACACCCCTGCGCGCNGCTCC3′ (Bmp2 5′pBam) and 5′ ATGGCTCGGGGCAGCCATCSTGGGCGA 3′ (BMP PCR 3.5). The fragment was phosphorylated at the 5′ end using 10 units of polynucleotide kinase and inserted into the SmaI site of the pGL2-basic vector.

Construct E (nt -147 to 494, pGL2 h656x or pGL3 h656x). A fragment containing -147 nt to 494 nt was generated by PCR using primers 5′ CGTCCACACCCCTGCGCGCNGCTCC3′ (Bmp2 5′pBam) and 5′ GGGCNCATTCTCGAGCGAGTCGAGC 3′ (RevBmp2XhoI) which introduced a XhoI site in the PCR generated fragment. This PCR fragment was phosphorylated at the 5′ end using 10 units of polynucleotide kinase, digested with XhoI and then inserted into the SmaI and XhoI site of the pGL2 basic or pGL3 basic vector.

Construct C – ECR1 (pGL3hhB2PvNc-mECR1). A 656 bp fragment containing the ECR-1 enhancer [42] was inserted into the unique KpnI site of construct C.

Construct E – ECR1 (pGL3h656x-mECR1). A 656 bp fragment containing the ECR-1 enhancer [42] was inserted into the unique KpnI site of construct E.

Mouse Bmp2 promoter reporter gene constructs

-2.7 kb mBmp2 (nt -1976 to 900 relative to the mouse distal promoter). A fragment spanning -1976 to +900 (a.k.a. -2712/+165 relative to the proximal promoter [23]) was subcloned from a plasmid (a gift from Drs. Ming Zhao and Steve Harris, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) into pGL2 basic.

ECR1 -2.7 kb mBmp2. A 656 bp fragment containing the ECR-1 enhancer [42] was inserted into the unique KpnI site of -2.7 kb mBmp2.

ECR1 -1.7 kb mBmp2 (nt -1237 to 471 relative to the mouse distal promoter with the ECR1). A 656 bp fragment containing the ECR-1 enhancer [42] was inserted into the unique KpnI site of pGL1.7XX [36].

Statistical analysis

Data is shown as average ± SEM. The statistical significance of difference between average values was determined by a Student's t test (two-sample assuming unequal variances). P values less than 0.05 were considered significantly different.

Results

Repressor elements flanking the BMP2 promoter sequence

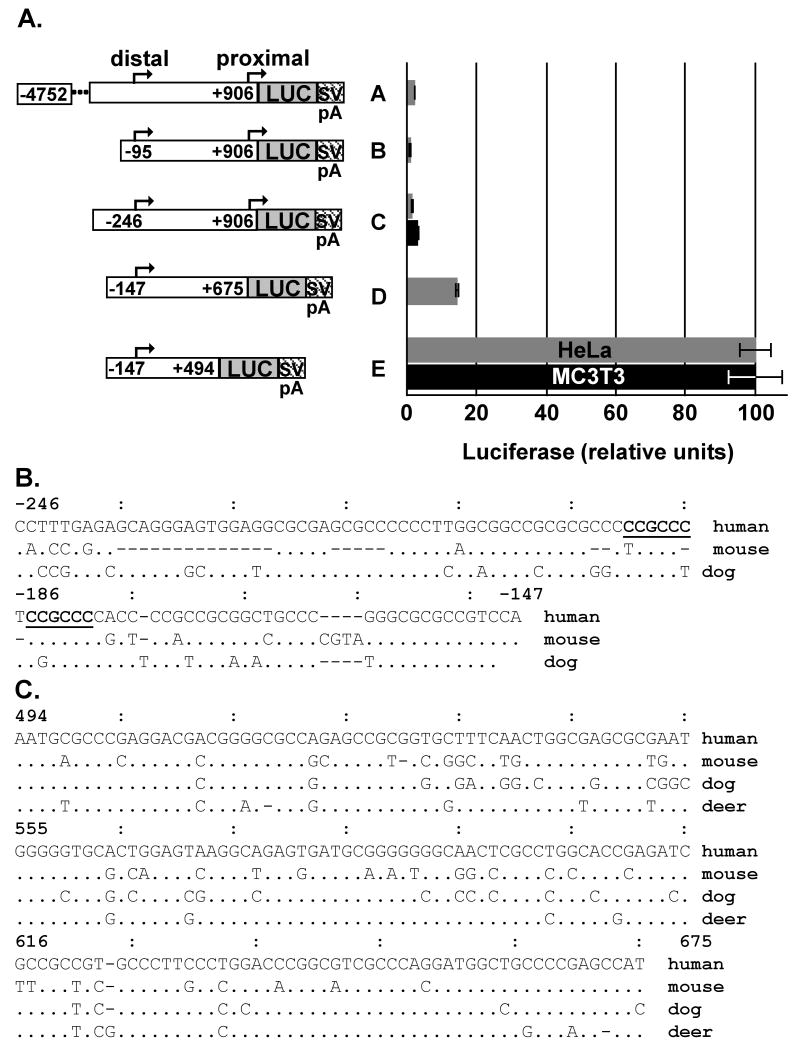

Our earlier analyses of the Bmp2 promoter region in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells found that a 4 kb fragment containing both the distal and proximal promoters was less active than the 1.7 kb fragment bearing only the distal promoter and upstream sequence [40]. Therefore, we hypothesized that repressive elements are located downstream from the distal Bmp2 promoter. We tested various human BMP2 gene promoter constructs in HeLa cells, which are known to express BMP2 RNA [19]. Luciferase reporter genes with a 5.6 kb sequence containing the distal and proximal promoters of human BMP2 (nt -4752 to 906 relative to the distal promoter, construct A) or nt. -95 to 906 and nt. -246 to 906 (constructs B and C, respectively) were expressed poorly (Fig. 1A). In contrast, construct D (nt -147 to 675) was expressed five fold more strongly (Fig. 1A, construct A vs. construct D). Furthermore, construct E (nt -147 to +494) was expressed at least 40 fold over the 5.6 kb construct A (Fig. 1A, construct A vs. construct E). Because pre-osteoblast cells are particularly sensitive to BMP2 levels, we also compared the expression of constructs C and E in MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells. Construct E was expressed 36 fold over construct C (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Repressive elements upstream and downstream of the BMP2 promoter.

A. Luciferase activity generated in HeLa (gray bars) cells after 24 hours of transfection or MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast (black bars) cells after 48 hours of transfection with reporter constructs containing different portions of the human BMP2 promoter (BMP) region cloned upstream of the luciferase gene (LUC) in pGL2 basic or pGL3 basic vectors. SVpA indicates the SV40 polyadenylation signal in the vector. Nucleotide positions are indicated relative to the distal promoter of human BMP2. Luciferase values were normalized to total protein amount in the transfected cells. Luciferase/protein values were graphed relative to the activity of construct E containing the same pGL2 or pGL3 basic vector background. Average reporter activity is shown ± S.E.M. In HeLa, n = 2 – 6, except construct B, n = 1. In MC3T3, n – 6. B. C. The BMP2 upstream region nt -246 to -147 (B) or nt 494 to 675 (C) relative to the human distal promoter, human (Homo sapiens, AF040249) and the corresponding sequences from mouse (M. musculus, NW_000178), dog (C. familiaris, NC_006606.2) and deer (Dama dama, AF041421) were aligned with MultiPipMaker (bio.cse.psu.edu/pipmaker). Identical nucleotides are indicated by “·”; gaps by “-”. Canonical Sp1 sites (GGGCGG) in the reverse orientation [37] are bold-faced and underlined in B.

These data suggest that repressive elements between nt -246 to -147 and nt 494 to 675 relative to the distal promoter down regulate BMP2 reporter gene activity in HeLa and MC3T3-E1 cells. We aligned the upstream region to the human, mouse and dog genomic sequences (Fig. 1B) and the downstream sequence to these sequences and the deer cDNA sequence (Fig. 1C). These alignments showed that these regions are conserved between species from three or four mammalian orders, respectively (Primates, Rodentia, Carnivores, and Artiodactyls). The nucleotide content of the upstream region shown in Fig. 1B has an 83% GC content and contains sequences that bind Sp1 and Sp3 [37]. The downstream region is 65% GC overall with shorter stretches of greater GC content (Fig. 1C). Conservation of such highly GC-rich repressive elements indicates an important role for these sequences in BMP2 gene regulation.

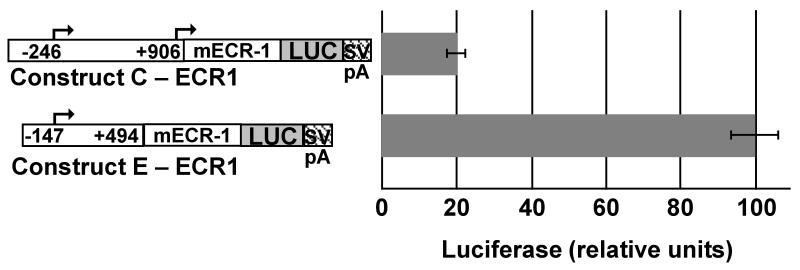

Promoter proximal repressors block the function of a conserved enhancer

We previously demonstrated that a conserved enhancer (ECR-1) located 156.3 kb downstream of the promoter drove the expression of mouse Bmp2 reporter transgenes bearing a minimal Hsp68 promoter in differentiating osteoblasts of both endochondral and intramembranous bones [42]. We compared the effect of ECR-1 on the activity of constructs C and E in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells. The shorter construct E with ECR-1, but without the repressor regions, was 5 times as active as the longer construct C with ECR-1 (Fig. 2). Thus, the repressive elements between nt -246 to -147 and nt 494 to 675 partly blocked the ability of the mouse ECR-1 enhancer to activate the human promoter.

Fig. 2. Effect of repressive elements on a conserved osteoblast BMP2 enhancer.

A. Luciferase activity in MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells after 42 to 48 hours of transfection with reporter constructs containing the indicated portions of the human BMP2 promoter (BMP) region and a 656 bp enhancer (mECR-1, [42]) cloned upstream of the luciferase gene (LUC) in the pGL3 basic vectors. SVpA indicates the SV40 polyadenylation signal in the vector. Nucleotide positions are indicated relative to the distal promoter of human BMP2. Luciferase values were normalized to total protein amount in the transfected cells. Average relative reporter activity is shown ± S.E.M (n = 6).

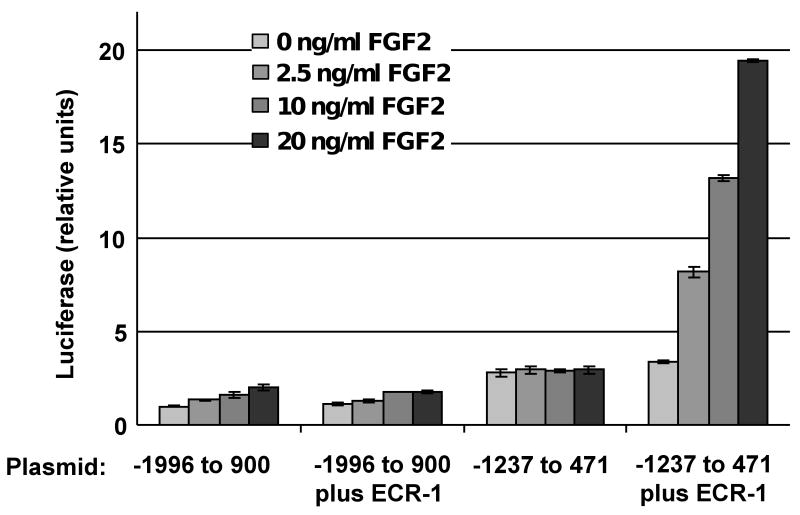

Promoter proximal repressors block the response of ECR-1 to FGF2

Given the effect of FGF-2 on Bmp2 expression in osteoblast progenitors [27; 28; 29], we hypothesized that the ECR-1 enhancer was involved in the induction of BMP2 by FGF2. We compared the activity of constructs bearing two different length mouse promoters with or without the ECR-1 enhancer in MC3T3-E1 cells with or without FGF-2. The 1.7 kb construct contained nt -1237 to 471 [36] while the 2.7 kb construct contained nt -1996 to 900. The mouse sequence between nt 471 and 900 is homologous to the human sequence that has repressor activity (Fig. 1). In the context of either the 2.7 kb or 1.7 kb promoter, ECR-1 enhancer activity was negligible in untreated cells, although the shorter promoter was about twice as active as the longer promoter (Fig. 3). However, the effect of FGF-2 on ECR-1 with the 1.7 kb promoter was dramatic. Specifically, FGF-2 induced the shorter promoter with the ECR-1 enhancer by up to seven fold in a dose dependent manner, but had no effect on the two constructs lacking ECR-1 or the 2.7 kb construct bearing ECR-1.

Fig. 3. Effect of repressive elements on FGF2 induction mediated by the ECR-1 osteoblast enhancer.

Luciferase activity of reporter constructs containing nt -1237 to 471 (pGL1.7XX) or nt -1996 to 900 (-2.7 kb mBmp2) of the mouse Bmp2 promoter region, with or without mECR-1, in the pGL2 basic vector in MC3T3-E1 cells. Nucleotide positions are indicated relative to the distal mouse promoter. Cells were transfected and then treated 24 hours later with the indicated amount of FGF2 or vehicle only (0.1% BSA), in serum-free media for a further 16-18 hours before harvesting. Luciferase values were normalized by cotransfection with a TK promoter-Renilla plasmid. Average relative reporter activity is shown ± S.E.M (n = 3) and normalized to the 2.7 promoter-only / zero FGF2 value.

Discussion

BMP2, like many genes that are tightly regulated by developmental and physiological signals, has a highly GC-rich promoter. We have shown that GC-rich sequences near the promoter inhibit reporter gene activity both in cells that constitutively transcribe the BMP2 gene (HeLa cells) and in cells that can be stimulated to express BMP2 (F9 cells [40] and MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts).

BMP2 is controlled by a complex network of proximal elements and distant regulatory elements located both upstream and downstream of the coding region. For instance, the region containing the ECR-1 sequence has been conserved over ∼310 myr of evolutionary divergence between birds and mammals [43]. This conserved region was necessary for osteoblast progenitor specific expression of a nearly 210 kb bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) reporter containing the endogenous BMP2 promoter [42]. Located 156 kb downstream from the BMP2 promoter, the ECR-1 sequence also activated expression of a lacZ gene under the control of the heterologous Hsp68 minimal promoter in osteoblast progenitors [42]. In contrast, the ECR-1 sequence failed to activate a 2.7 kb fragment with the promoter proximal repressor elements in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells (Figs. 1A, 2A). The strong FGF-2-responsiveness of the ECR-1 enhancer in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells was only revealed after the deletion of these repressors (Fig. 3).

The endogenous promoters and the promoters contained within the BAC transgenes are subject to regulation by numerous and distant activating sequences. Our data indicates that, if Bmp2 is to be transcribed, the combined effect of the activating factors must exceed the significantly repressive effect of sequences near the distal promoter.

Conclusions

BMP2 is a potent signal that regulates the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of many cell types including osteoblasts. As expected for a morphogen [44; 45], precise regulation of BMP2 levels is crucial [9]. Balancing activating and repressing gene regulatory mechanisms can precisely control BMP2 protein levels. In addition, BMP2 levels are dynamically regulated in diverse developing organs and during adult processes such as fracture repair. Tissue specific combinations of activating and repressing processes can control the highly complex spatial and temporal patterns of BMP2 gene expression.

The mapping of positive genetic regulatory elements controlling the mouse and human BMP2 genes has been slowed by the presence of repressive elements near the promoters. An awareness of the negative elements described here will facilitate characterizing the multitude of motifs required to direct normal BMP2 synthesis patterns in different tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Molecular Resource Facility at the UMDNJ – NJ Medical School (M.B.R.) and the National Institute of Health (R01HD31117 to M.B.R., R01HD47880 to D.P.M., 5T32HD07502 to R.L.C.)

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- FGF2

fibroblast growth Factor

- nt

nucleotides

- kb

kilobases

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RA

retinoic acid

- EC

embryonal carcinoma

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22:233–41. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celeste AJ, Iannazi JA, Taylor RC, Hewick RM, Rosen V, Wang EA, Wozney JM. Identification of transforming growth factor β family members present in bone-inductive protein purified from bovine bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9843–9847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urist M. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150:893–899. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3698.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA. Novel regulators of bone formation: Molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242:1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons K, Pelton R, Hogan B. Patterns of expression of murine Vgr-1 and BMP-2a RNA suggest that transforming growth factor-β-like genes coordinately regulate aspects of embryonic development. Genes & Devl. 1989;3:1657–1668. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons KM, Pelton RW, Hogan BLM. Organogenesis and pattern formation in the mouse: RNA distribution patterns suggest a role for Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2A (BMP-2A) Development. 1990;109:833–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstenfeld LC, Cullinane DM, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:873–84. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuji K, Bandyopadhyay A, Harfe BD, Cox K, Kakar S, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn T, Tabin CJ, Rosen V. BMP2 activity, although dispensable for bone formation, is required for the initiation of fracture healing. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1424–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Bradley A. Mice deficient for BMP2 are nonviable and have defects in amnion/chorion and cardiac development. Devl. 1996;122:2977–2986. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lelong C, Mathieu M, Favrel P. Identification of new bone morphogenetic protein-related members in invertebrates. Biochimie. 2001;83:423–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampath TK, Rashka KE, Doctor JS, Tucker RF, Hoffmann FM. Drosophila transforming growth factor b superfamily proteins induce endochondral bone formation in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1993;90:6004–6008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan B. Upside-down ideas vindicated. Nature. 1995;376:210–211. doi: 10.1038/376210a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers MB, Rosen V, Wozney JM, Gudas LJ. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins-2 and 4 are Involved in the Retinoic Acid-induced Differentiation of Embryonal Carcinoma Cells. Molec Biol Cell. 1992;3:189–196. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers M. Receptor-selective retinoids implicate RAR alpha and gamma in the regulation of bmp-2 and bmp-4 in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helvering LM, Sharp RL, Ou X, Geiser AG. Regulation of the promoters for the human bone morphogenetic protein 2 and 4 genes. Gene. 2000;256:123–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis PH, Richardson MK, Brickell PM, Tickle C. Bone morphogenetic proteins and a signalling pathway that controls patterning in the developing chick limb. Devl. 1994;120:209–18. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallahan AR, Pritchard JI, Chandraratna RA, Ellenbogen RG, Geyer JR, Overland RP, Strand AD, Tapscott SJ, Olson JM. BMP-2 mediates retinoid-induced apoptosis in medulloblastoma cells through a paracrine effect. Nat Med. 2003;9:1033–8. doi: 10.1038/nm904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin P, Haberbusch JM, Zhang Z, Soprano KJ, Soprano DR. Pre-B cell leukemia transcription factor (PBX) proteins are important mediators for retinoic acid-dependent endodermal and neuronal differentiation of mouse embryonal carcinoma P19 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16263–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang S, Zhang S, Langenfeld J, Lo SC, Rogers MB. Mycoplasma infection transforms normal lung cells and induces bone morphogenetic protein 2 expression by post-transcriptional mechanisms. J Cell Biochem. 2007;104:580–594. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh-Choudhury N, Choudhury GG, Harris MA, Wozney J, Mundy GR, Abboud SL, Harris SE. Autoregulation of mouse BMP-2 gene transcription is directed by the proximal promoter element. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:101–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S, Turgeman G, Harris SE, Leitman DC, Komm BS, Bodine PV, Gazit D. Estrogens activate bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transcription in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:56–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundy G, Garrett R, Harris S, Chan J, Chen D, Rossini G, Boyce B, Zhao M, Gutierrez G. Stimulation of bone formation in vitro and in rodents by statins. Science. 1999;286:1946–9. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng JQ, Xing L, Zhang JH, Zhao M, Horn D, Chan J, Boyce BF, Harris SE, Mundy GR, Chen D. NF-kappaB specifically activates BMP-2 gene expression in growth plate chondrocytes in vivo and in a chondrocyte cell line in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29130–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukui N, Zhu Y, Maloney WJ, Clohisy J, Sandell LJ. Stimulation of BMP-2 expression by pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and TNF-alpha in normal and osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A 3:59–66. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300003-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lories RJ, Derese I, Ceuppens JL, Luyten FP. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 6, expressed in arthritic synovium, are regulated by proinflammatory cytokines and differentially modulate fibroblast-like synoviocyte apoptosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2807–18. doi: 10.1002/art.11389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im GI, Qureshi SA, Kenney J, Rubash HE, Shanbhag AS. Osteoblast proliferation and maturation by bisphosphonates. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fakhry A, Ratisoontorn C, Vedhachalam C, Salhab I, Koyama E, Leboy P, Pacifici M, Kirschner RE, Nah HD. Effects of FGF-2/-9 in calvarial bone cell cultures: differentiation stage-dependent mitogenic effect, inverse regulation of BMP-2 and noggin, and enhancement of osteogenic potential. Bone. 2005;36:254–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi KY, Kim HJ, Lee MH, Kwon TG, Nah HD, Furuichi T, Komori T, Nam SH, Kim YJ, Ryoo HM. Runx2 regulates FGF2-induced Bmp2 expression during cranial bone development. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:115–21. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naganawa T, Xiao L, Coffin JD, Doetschman T, Sabbieti MG, Agas D, Hurley MM. Reduced expression and function of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in bones of Fgf2 null mice. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1975–88. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canalis E, Economides AN, Gazzerro E. Bone morphogenetic proteins, their antagonists, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:218–35. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanagita M. BMP antagonists: their roles in development and involvement in pathophysiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill CS. Turning off Smads: identification of a Smad phosphatase. Dev Cell. 2006;10:412–3. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devaney JM, Tosi LL, Fritz DT, Gordish-Dressman HA, Jiang S, Orkunoglu-Suer FE, Gordon AH, Harmon BT, Thompson PD, Clarkson PM, Angelopoulos TJ, Gordon PM, Moyna NM, Pescatello LS, Visich PS, Zoeller RF, Brandoli C, Hoffman EP, Rogers MB. Differences in fat and muscle mass associated with a functional human polymorphism in a post-transcriptional BMP2 gene regulatory element. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:1073–82. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukui N, Ikeda Y, Ohnuki T, Hikita A, Tanaka S, Yamane S, Suzuki R, Sandell LJ, Ochi T. Pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces bone morphogenetic protein-2 in chondrocytes via mRNA stabilization and transcriptional up-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27229–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrams KL, Xu J, Nativelle-Serpentini C, Dabirshahsahebi S, Rogers MB. An evolutionary and molecular analysis of Bmp2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15916–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J, Rogers MB. Modulation of Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) 2 gene expression by Sp1 transcription factors. Gene. 2007;392:221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hapgood JP, Riedemann J, Scherer SD. Regulation of gene expression by GC-rich DNA cis-elements. Cell Biol Int. 2001;25:17–31. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2000.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L, He S, Sun JM, Davie JR. Gene regulation by Sp1 and Sp3. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:460–71. doi: 10.1139/o04-045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heller LC, Li Y, Abrams KA, Rogers MB. Transcriptional Regulation of the Bmp2 Gene: Retinoic Acid Induction in F9 Embryonal Carcinoma Cells and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1394–1400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng JQ, Chen D, Ghosh-Choudhury N, Esparza J, Mundy GR, Harris SE. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 transcripts in rapidly developing deer antler tissue contain an extended 5′ non-coding region arising from a distal promoter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1350:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandler RL, Chandler KJ, McFarland KA, Mortlock DP. Bmp2 transcription in osteoblast progenitors is regulated by a distant 3′ enhancer located 156.3 kilobases from the promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2934–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ureta-Vidal A, Ettwiller L, Birney E. Comparative genomics: genome-wide analysis in metazoan eukaryotes. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:251–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raftery LA, Sutherland DJ. Gradients and thresholds: BMP response gradients unveiled in Drosophila embryos. Trends Genet. 2003;19:701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent JP, Briscoe J. Morphogens. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R851–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]