Abstract

Malignant melanoma is the most common metastatic tumor of the gastrointestinal tract and can present with fairly common constitutional symptoms. A 36-yr-old woman was found to have a secondary malignant melanoma in the terminal ileum with profuse aneurysmal dilatation, which is not the typical presentation of the malignant melanoma in the small intestine. Radiologic studies revealed a large tumor involving the distal ileum with aneurysmal dilatations having afferent and efferent loops, which needed to be differentiated from malignant lymphoma and other gastrointestinal tumors. Exploratory laparotomy was done, and we found a huge mass with plentiful aneurysmal dilatations; much the same of the findings from the previous studies. Segmental resection with the surrounding omentum was done followed by end-to-end anastomosis between both ends of the remaining ileum. She had been free from any evidence of the local or systemic recurrence for one year after the completion of eighteen months of the subcutaneous interferon treatment; postoperatively however, the occurrence of metastatic mass at the right axilla rendered us from complete resection due to severe penetration into the vital nerves and vessels in the axilla.

Keywords: Malignant Melanoma, Gastrointestinal Neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Malignant melanoma, originated from melanocytes, is not a common cancer and is found only in about 1-3% of all cancer patients (1). Its incidence in Korea is still low, not reaching at 1% (2). Distant metastasis through the lymphatic and hematogenous pathway is frequent in malignant melanoma. Although metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract is invariably found in about 50-60% of autopsy cases, the incidence of being found alive is about 4% (3, 4); the small intestine is the most commonly involved site in the gastrointestinal tract. Primary malignant melanoma, though extremely rare, has been reported. However the presence of primary malignant melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract other than the esophagus and rectum where melanocytes normally exist, is controversial (5, 6). We experienced a case of malignant melanoma having aneurysmal dilatations with no confirmed primary lesion.

CASE REPORT

A 36-yr-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of intermittent fever, chill, indigestion and colicky abdominal pain that had developed about three weeks ago. On admission, her vital signs were unstable. The blood pressure was at 80/60 mmHg, the pulse was at 110/min but normal, the respirations were at 20/min, and the temperature was at 38℃. On physical examination, she showed abdominal distension with moderate tenderness of the lower abdomen but no rebound tenderness. A spherical mass was palpated at the lower abdomen but the bowel sound was normal. Pitting edema was observed in both legs.

After laboratory workup, severe anemia was unveiled: The hemoglobin was 4.3 mg/dL, the hematocrit 12.9%, the white-cell count 23,600/µL (segment neutrophil 77%), the platelet count 685,000/µL, reticulocyte 2.3%, MCH 26 picograms, MCV 77.7 femtoliters, MCHC 33.4%, serum iron 5 µg/dL, and total iron-binding capacity 131 µg/dL. Peripheral blood smears yielded two plus for toxic granules and the Coomb's test was negative. On biochemical study, the level of serum sodium was low at 129 mEq/L, while potassium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, urea nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine transferase were normal. Bone marrow biopsy was followed for the evaluation of her anemia. It resulted in the typical feature of a chronic disease; cellularity of 70-80%, G:E ratio of 10:1, and granulocytic hyperplasia of the bone marrow. Endoscopic evaluations were performed to rule out the possibility of anemia from the intestinal origin with no abnormal findings found in the stomach, duodenum, colon, and rectum. On radiologic evaluation, slight hypertrophy of the heart was found on plain chest radiograph. A mass accompanied by numerous aneurysmal dilatations at the terminal ileum was initially found by the ultrasonography, which is usually the finding of a lymphoma or submucosal tumor with ulcer. Small amount of ascites, slight splenomegaly, and a benign-looking hepatic cyst were also found on ultrasonography. A computed tomography was followed, which showed exactly the same findings of ultrasonography (Fig. 1). According to the small bowel series along with the previous radiologic findings, a lymphoma or gastrointestinal stromal tumor having marked aneurysmal dilatations was suspected (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computerized tomography shows marked dilatation of the distal ileum and no obstructive lesion.

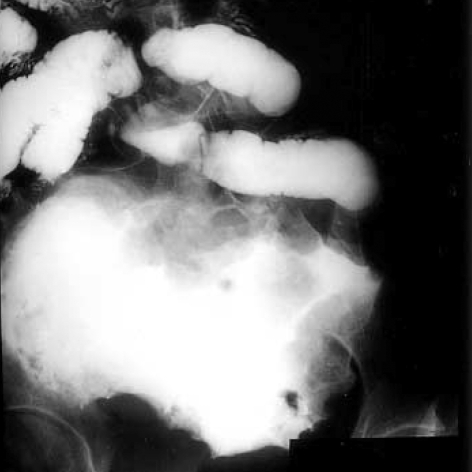

Fig. 2.

Small bowel series shows submucosal tumor at distal ileum, suggesting a lymphoma with aneurysmal dilatations or gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

After treating anemia with repeated transfusion, exploratory laparotomy was done. After evacuating moderate amount of intraabdominal ascites, we could locate a mass at the terminal ileum, which resided in the middle of the lower abdomen and attached firmly to the omentum anteriorly, the sigmoid colon posteriorly, and the urinary bladder inferiorly. The diameter of the mass exceeded 15 centimeters, and the intervening normal segment of the ileum between the mass and the ileocecal valve was 10 centimeters in length. The mass had serpentine aneurysmal dilatations around it, but no lymphadenopathy was found around the mass. The patient underwent segmental resection of the involved ileum along with the mesentery. Unfortunately, we had to sacrifice her right adnexa and some part of the bladder wall due to severe adhesion with the mass. By dividing the mass longitudinally, we could see a necrotic tumor with nodules on the serosal surface of the diseased ileum having normal looking proximal and distal small intestinal loops attatched to it (Fig. 3). Grossly, the specimens were previously opened and continuous segment of terminal ileum, 44 cm long, and cecum and ascending colon, 18 cm long. The lumen of the small intestine was markedly dilated, about 15 cm in diameter, at 26 cm from the proximal margin of resection and showed tan gray dull and nodular serosal surface. It showed diffusely thickened wall, up to 25 cm, and showed tan gray nodular luminal surface. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections of the small intestine showed infiltration of the nests of epithelioid tumor cells. The tumor cells showed marked cytologic atypia with large eosinophilic nucleoli, abundant mitotic figures, and abundant cytoplasm (Fig. 4). Melanin pigment was focally present in the cytoplasm. After immunohistochemical staining with HMB-45 and S-100, the diagnosis of the malignant melanoma infiltrating to the ileal mucosa was confirmed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

There is markedly dilated lumen in the mass in connection with the lumen of afferent loop (arrowhead) and efferent loop with normal ileal mucosa (arrow).

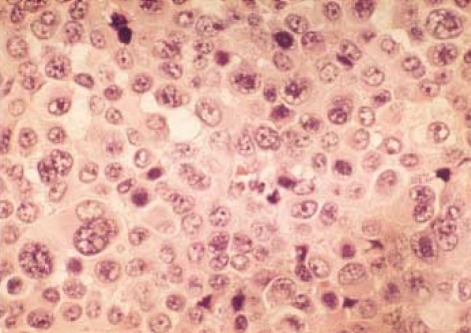

Fig. 4.

The microscopic findings of the tumor cells are markedly irregular in size and shape, showing large cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. (H&E stain, ×400).

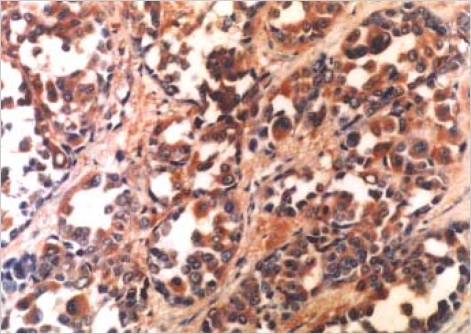

Fig. 5.

Result of immunohistochemical staining with HMB-45 is positive (×200).

Thorough postoperative systemic evaluations were done to disclose the primary site of the malignant melanoma but ended without significant results. We did find a nevus at the left upper lip, but biopsy results only revealed it as a melanocytic nevus within the dermis.

Since the first operation, she had had systemic interferon treatment for eighteen months. During the period of systemic therapy, she did not show any evidence of local or systemic recurrence. After the eighteen months of the treatment, we could not continue to follow up on her. About one year after the initial operation, however, she visited our hospital with a huge mass measuring at 15 cm in diameter at her right axilla. The mass showed very aggressive phenotype and at the second operation we failed to remove the mass completely due to its penetration and invasion into the nerves and vessels in the axilla. The histopathological examination with immunohistochemical staining confirmed the recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Malignant melanoma is a relatively rare tumor comprising 1-3% of all tumors. Mucosal melanoma is especially rare with its rate of incidence of only 3% in Caucasians. Although metastasis of malignant melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract is frequently seen in autopsy cases up to 50-60%, only two to five percent of patients are diagnosed with malignant melanoma while they are alive (3, 4, 7). It is because that there are no specific symptoms of early development, which are general and constitutional; and even if they do occur, they are usually accompany with symptoms such as abdominal pain (62%), hemorrhage (50%), nausea and vomiting (26%), mass (22%), and intestinal obstruction (18%), so it usually is diagnosed in the emergency situation after metastasis occurs (8). Metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract is seen most frequently in the small intestine, followed by the colon, stomach, and rectum but is rare in the esophagus. However, primary malignant melanoma originating in the small intestine is extremely rare. Characteristically, the time interval between the identification of the primary malignant melanoma to the diagnosis of metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract can be long from 2 to 180 months, and the primary lesion is not be defined in 8% (8, 9). It was suggested that the primary lesion may be lost naturally, or small and extensive metastasis could occur before any changes are observed (10). The following diagnostic criteria are proposed, though the controversy still exists over the presence of primary malignant melanoma in areas other than the esophagus and rectum. According to Sachs et al., primary malignant melanoma is diagnosed in the small intestine where there are 1) biopsy-proven melanoma from the small intestine at a single focus, 2) no evidence of disease in any other organs including the skin (no evidence of regressed primary melanoma), eye and lymph nodes outside the regional drainage at the time of diagnosis, and 3) disease-free survival of at least 12 months after diagnosis (11). According to Blecker et al., it is diagnosed when there are lack of concurrent or previous removal of a melanoma or atypical melanocytic lesion from the skin and lack of other organ involvement and in situ change in the overlying or adjacent GI epithelium (12). Allen and Spitz claimed that the diagnosis is made when there are 1) characteristic structure of melanoma and melanin pigment, 2) presence of melanocytes in the adjacent epithelium, 3) polypoidal growth, and 4) when melanoma is originated from the areas having junctional activity within the squamous epithelium (13). However, these criteria are fit only in 40% of esophagus melanoma considered as primary malignant melanoma (14). More than 50% of the lesions of the small intestine are polypoid. Aneurysmal dilatation in the small intestine seen in our patient showed the typical findings of malignant lymphoma. There are the following five characteristic appearances of lymphomatous involvement of the small intestine according to radiologic classification: 1) multiple intraluminal nodular defects; 2) polypoid form causing intussusception; 3) endo-exo-enteric form with excavation and multiple fistula formations; 4) invasive form of the mesentery with large extraluminal masses; and 5) infiltrating form (15). The aneurysmal form belongs to the fifth one. Aneurysmal dilatations are the results of the diffuse infiltration of the intestinal segment. As they advance, destruction by the tumor becomes so extensive that the lumen appears as a large cavity. Although aneurysmal dilatation that we encountered is seen more frequently in a primary tumor such as lymphoma, or leiomyosarcoma, some studies report that such form can appear in lesions of the small intestine metastasized from primary lesions such as malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, adenocarcinoma of the rectum, and endometrial stromal sarcoma (16), indicating that this metastaic lesion with aneurysmal dilatation may be hematogeneous in origin. Enteroclysis was suggested as a method for diagnosis, but is unreliable in demonstrating melanoma metastases to the small bowel, as is computerized tomography. Primary treatment for malignant melanoma is an extensive and curative surgery, if possible, because other methods including radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy cannot offer definite treatment outcome. It is known that the prognosis of mucosal melanoma is poor compared with the malignant melanoma of the skin and prognosis is also poor when metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract is present, with the average survival period being 4-6 months (17). However, the median length of survival was reported to be from 23 to 48 months when complete surgical resection was possible (8). Early diagnosis is important in treating malignant melanoma, since the primary modality of treatment is surgical operation. The aggressive surgical resection is essential even in the presence of metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract, since surgery is not only a palliative modality but also affects the prognosis (2, 17); so it should be considered primarily in selected patients.

Though the possibility of primary malignant melanoma in the small intestine do exist, the incidence is extremely low. Though the previous nevus near the mouth seemed not likely to be the primary focus in the present case, we could not completely rule out the possibility. The pattern of growth of the small intestinal lesion was not polypoid and melanocytes were not found in the adjacent epithelium. So, we presumed the lesion at the terminal ileum to be the secondary malignant melanoma from an unknown primary site.

Ileal malignant melanoma with diffuse serpentine aneurysmal dilatation is an extremely rare and unusual condition, which must be differentiated from other intestinal tumors, but it is not possible to obtain a definite diagnosis before the pathological confirmation. Immunohistochemical staining with antimelanoma antibody and HMB-45 is, however, found to substantiate the diagnosis.

In conclusion, metastatic melanoma in the small bowel should be suspected in any patient with a previous history of malignant melanoma or atypical melanocytic nevus who develops gastrointestinal symptoms or chronic blood loss leading to moderate or severe anemia. Presenting symptoms are nonspecific such as anemia, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Small bowel involvement by melanoma, even without a known primary focus, is most probably metastatic. Surgical treatment is the first choice; the prognosis after surgical resection was much better than for other organ metastases or simultaneous metastases of the small bowel and other organs. There appear to be two subsets of primary melanoma: one that occurs among younger patients, which is more aggressive with rapid metastases and early death and another one that occurs among older patients, being more indolent with less rapid metastasis (18). The relatively high 5-yr survival rate associated with complete surgical resection of gastrointestinal tract metastases indicates that surgery should be strongly considered for this type of patients.

References

- 1.Markowitz JS, Cosimi LA, Carey RW, Kang S, Padyk C, Sober AJ, Cosimi AB. Prognosis after initial recurrence of cutaneous melanoma. Arch Surg. 1991;126:703–708. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410300045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SY, Youn YK, Choe KJ. Surgical treatment of malignant melanoma. J Korean Cancer Assoc. 1990;22:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das Gupta TK, Brafield RD. Metastatic melanoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1964;17:1323–1339. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196410)17:10<1323::aid-cncr2820171015>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klaase JM, Kroon BB. Surgery for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1990;77:60–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadivar TF, Vanek VW, Krishnan EU. Primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel: A case study. Am Surg. 1992;58:418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson BG, Anderson JR. Malignant melanoma involving the small bowel. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:355–357. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.62.727.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135:807–810. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger AC, Buell JF, Venzon D, Baker AR, Libutti SK. Management of symptomatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;6:155–160. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oddson TA, Rice RP, Seigler HF, Thompson WM, Kelvin FM, Clark WM. The spectrum of small bowel melanoma. Gastrointest Radiol. 1978;3:419–423. doi: 10.1007/BF01887106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JY, Go YC, Kim JK, Shin SH, Cho SW, Seo KS, Kang MW, Lim YK, Yeo HS, Kim KS. A case of malignant melanoma metastasized to entire gastrointestinal tract including the esophagus. Chonnam Med J. 2000;37:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs DL, Lowe L, Chang AE, Carson E, Johnson TM. Do primary small intestinal melanomas exist? Report of a case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1042–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3427–3433. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen AC, Spitz S. Malignant melanoma: a clinicopathological analysis of criteria for diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer. 1953;6:1–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195301)6:1<1::aid-cncr2820060102>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Matos P, Wolfe WG, Shea CR, Prieto VG, Seigler HF. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. J Surg Oncol. 1997;66:201–206. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199711)66:3<201::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norfray J, Calenoff L, Zanon B., Jr Aneurysmal lymphoma of the small intestine. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119:335–341. doi: 10.2214/ajr.119.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zornoza J, Goldstein HM. Cavitating metastases of the small intestine. Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:613–615. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D. Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:181–185. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsayed AM, Albahra M, Nzeako UC, Sobin LH. Malignant melanomas in the small intestine: a study of 103 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1001–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]