Abstract

The incidence of melanoma is rising at an alarming rate and we are still awaiting an effective treatment for this malignancy. In its early stage, melanoma can be cured by surgical removal, but once metastasis has occurred there is no effective treatment. Recent findings have suggested multiple functional implications of CXCL8 and its cognate receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, in melanoma pathogenesis, thus underscoring their importance as targets for cancer therapy. This review provides an update on the roles of CXCL8 and its receptors in melanoma progression and metastasis.

Keywords: CXCL8, CXCR1, CXCR2, melanoma

Chemokines are secreted, low-molecular-weight chemotactic proteins (8–11 kDa) that regulate the trafficking of leukocytes to inflammatory sites. There are more than 50 chemokines and over 20 chemokine receptors characterized, to date [1]. Chemokines have conserved cysteine residues that play important roles in their structural conformation and function. Structurally, chemokines are divided into four families based upon the position of their conserved two N-terminal cysteine-residues (CXC, CC, C and CX3C) [1,2]. Members of the CXC contain one amino acid between the first and second cysteine residues, CC chemokines have adjacent cysteine residues, the C subfamily has only one cysteine residue and CX3C chemokines have three amino acids between the first two cysteines. Chemokines exert their biological function by binding to a specific family of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), generally referred to as chemokine receptors. Chemokine receptors possess seven hydrophobic transmembrane domains, three extracellular and three intracellular loops and have an extracellular N-terminus and an intracellular C-terminus (containing serine and threonine phosphorylation sites). To date, seven CXC receptors, ten CC receptors, and one receptor each for C and CX3C chemokines have been identified [1,2]. The most potent and best-characterized human CXC chemokine is CXCL8, and its role in inflammation, infection and other disease states has been studied intensively. A murine homologue for CXCL8 has not yet been identified, but it has been suggested that the role of CXCL8 in neutrophil recruitment is executed by CXCL6 in mice [3]. Before CXCL8, CXCL1 (Gro) was discovered as melanoma growth stimulatory activity (MGSA) [4,5].

CXCL8 binds to two receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, with similar high affinity, and initiates downstream signaling events to mediate cellular responses. CXCR1 and CXCR2 were the first chemokine receptor subtypes to be defined and are the only known mammalian receptors for those chemokines with a specific amino acid sequence (or motif) of glutamic acid–leucine–arginine (or ELR for short) immediately before the first cysteine of the CXC motif (ELR-positive), including CXCL8. CXCR1 interacts with CXCL8 and CXCL6, whereas CXCR2 interacts with CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, epithelial cell-derived neutrophil attractant 78 (CXCL5), CXCL6 and neutrophil-activating peptide-2 (CXCL7) [6].

Malignant melanoma is a malignant tumor arising from the melanocytes that usually occurs on the skin and is linked to ultraviolet sunlight exposure. Melanoma is the sixth most common cancer in the USA and, according to the American Cancer Society estimate, approximately 68,720 new cases of melanoma will be identified and 8650 deaths will occur due to this malignancy during 2009 [7]. The chance of developing melanoma increases with age, but melanoma affects all age groups and is one of the most common cancers in young adults. Most often, benign nevi can progress to radial growth-phase melanomas, which can progress further to the more aggressive vertical growth phase that exhibits metastatic potential [8,9]. Melanoma tissues and derived cell lines have been demonstrated to express a variety of chemokines, including CXCL8 and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 [9,10]. In this review, we will discuss the multifaceted roles of CXCL8 and its receptors in melanoma progression and metastasis.

CXCL8 & its receptors in melanoma tumor progression

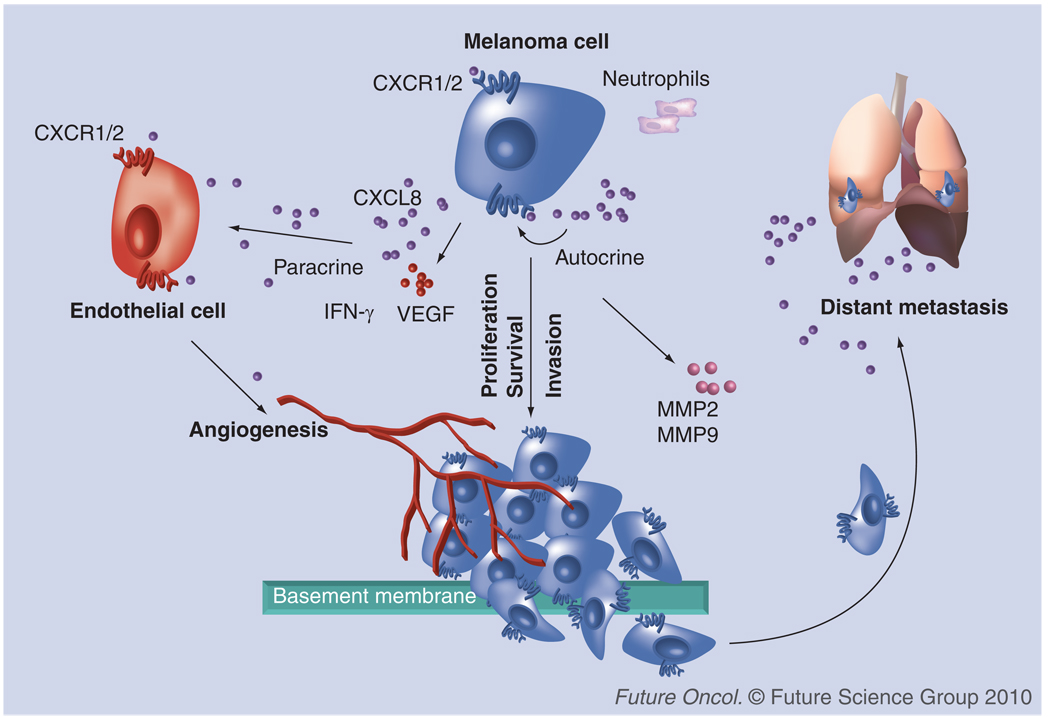

Although, chemokines were first identified as chemoattractants of leucocytes, it has now been well-recognized that any cell type can express chemokines and chemokine receptors. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the interaction between chemokines and their receptors plays an important role in regulating various steps of tumor development, including tumor growth, progression and metastasis (Figure 1). In the case of melanoma, several reports strongly support the idea that tumor cells take advantage of the expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors to stimulate the immune response, induce tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth, alter the tumor microenvironment and facilitate metastasis to a secondary site [1]. CXCL8 was the first chemokine reported to induce melanoma cell chemotactic and haptotactic migration [11]. CXCL8 acts as an autocrine/paracrine growth factor and influences the process of melanoma progression by activating CXCR1 and CXCR2 [11–13]. The expression of CXCL8, as well as its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, in melanoma has demonstrated a positive correlation with disease progression [14,15]. Ultraviolet-B radiation was also demonstrated to stimulate the production of CXCL8, which, in turn, enhanced the migration of metastatic melanoma cells in vitro [16]. Overexpression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in melanoma cells confers the aggressive phenotypes on melanoma cells based on enhanced proliferation, migration and tumor growth in mice [13]. Furthermore, knockdown, or the use of an antagonist or neutralization of these receptors affects cell proliferation, survival and migration, strongly indicating that these receptors are involved in melanoma progression [17]. Additional evidence in support of the role of CXCR2 in tumor–host microenvironment comes from a recent study [18]. It was demonstrated that the growth of melanoma tumors was significantly suppressed when human melanoma cells were injected in CXCR2-knockout athymic mice. Together, these studies clearly indicate an important role of CXCL8 and its receptors in melanoma progression.

Figure 1. CXCL8 and its receptors in different steps for melanoma progression and metastasis.

CXCL8 is produced by malignant cells and promotes their proliferation, survival and migration through interaction with CXCR1 and/or CXCR2. Moreover, tumor-derived CXCL8 regulates leukocyte infiltration and neovascularization, modulating the tumor microenvironment for progression and metastasis. Chemokines can stimulate specific receptors that alter the adhesive capacity of tumor cells, their migration/invasion into circulation and extravasation towards specific organs, leading to the establishment of distant metastasis.

CXCL8 & its receptors in melanoma angiogenesis

CXCL8 and its receptors can affect tumor growth, not only directly, but also indirectly, by promoting angiogenesis. The ability of CXCL8 to elicit angiogenic activity depends on the expression of its receptor by endothelial cells. Recent studies indicate that CXCR1 is highly and CXCR2 is moderately expressed on human microvascular endothelial cells, whereas human umbilical vein endothelial cells express low levels of CXCR1 and CXCR2 [19]. Neutralizing antibodies to CXCR1 and CXCR2 abrogated CXCL8-induced migration of endothelial cells, indicating that these two receptors are critical for the CXCL8-mediated angiogenic response [19,20]. Other studies have also highlighted the importance of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in angiogenesis [9,13,18,21]. Of these two high-affinity receptors for CXCL8, the importance of CXCR2 in mediating chemokine-induced angiogenesis was demonstrated to be fundamental in CXCL8-induced neo-vascularization [22,23]. CXCL8 stimulates both endothelial proliferation and capillary tube formation in vitro in a dose-dependent manner, and both of these effects can be blocked by monoclonal antibodies to CXCL8 [24,25]. In addition, it has been reported that there is a direct correlation between high levels of CXCL8 and tumor angiogenesis, progression and metastasis in nude xenograft models of melanoma [26,27]. In a recent study, modulation of BclxL in tumor cells was demonstrated to regulate the angiogenesis by upregulating CXCL8 expression [28]. Endothelin-1 was also demonstrated to induce the secretion of CXCL8 in human melanoma cell lines, implicating its role in melanoma progression [29]. Besides other mechanisms, CXCL8 exerts its angiogenic activity by upregulating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 in tumor and endothelial cells [20,26,30]. Degradation of the extracellular matrix by MMPs is required for endothelial cell migration, organization and hence, angiogenesis [31,32]. It has been demonstrated, that CXCL8 directly enhances endothelial cell proliferation, survival and MMP expression in CXCR1- and CXCR2-expressing endothelial cells, indicating that it may be an important player in the process of angiogenesis [24]. Interestingly, a recent study reported that CXCL8 upregulates VEGF expression in endothelial cells by acting on its cognate receptor, CXCR2, and thereby promotes the activation of VEGF receptor in an autocrine fashion [33]. In another study, it has been observed that the N-terminal truncation of CXCL8 enhances its angiogenic activity via, as yet, undefined mechanism(s) [34].

CXCL8 & its receptors in melanoma metastasis

Tumor cell proliferation and migration (invasion) are important components of the metastatic process. CXCL8 and its receptors have been implicated in melanoma progression through several mechanisms, including the promotion of tumor cell growth and migration [11,13,35,36]. A previous study demonstrated a correlation between CXCL8 expression and metastatic behavior in human melanoma cells in nude mice [14]. Additionally, in a nude mouse model, ultraviolet-B radiation induced the expression of CXCL8 mRNA and protein, and potentiated the melanoma cell tumorigenesis and metastasis [37]. It has also been demonstrated that metastatic variants of melanoma cells express higher levels of CXCL8 protein when compared with the nonmetastatic variant [37,38]. Elevated serum levels of CXCL8 in patients with metastatic melanoma and hepatocellular carcinoma have also been reported to correlate with tumor burden and poor prognosis [15,39]. CXCL8 in tumor specimens from different stages of melanoma is differentially expressed in radial growth phase (melanoma in situ) and vertical growth phase (invasive) primary malignant melanoma and subcutaneous, muscle and lymph node metastases. While the radial growth phase tumors did not show any staining for CXCL8, 50% of the vertical growth phase tumors were positive and showed a heterogeneous pattern of staining. Interestingly, an intense CXCL8 immuno-reactivity was observed in the metastatic lesions from skin, muscle and lymph node [8,9]. Similar results have been demonstrated in another study showing a correlation between CXCL8 expression and tumor depth [40]. These data suggest an association between the expression of CXCL8 and metastasis in human cutaneous melanoma. Additionally, a concomitant upregulation of one of the two putative CXCL8 receptors has been reported in human melanoma specimens. Analysis of CXCR1 in human melanoma specimens from different Clark levels demonstrated that it is expressed ubiquitously in all Clark levels. By contrast, CXCR2 is predominantly expressed by higher-grade melanoma tumors and metastases, suggesting an association between expression of CXCL8 and CXCR2 with vessel density in advanced lesions and metastases [9]. More specifically, the effect of CXCL8 can be mediated by CXCR1 and CXCR2, with CXCR1 being a selective receptor for CXCL8 [22]. In vivo murine studies using knock-out models demonstrated that CXCR2 played a major role in melanoma metastasis to the lung [18]. Overall, the aberrant expression of CXCL8 and its receptors may be a common feature of melanoma. From the functional significance of its receptors, we can contemplate that the expression of CXCL8 and its receptors (CXCR1/CXCR2) plays a key role in deciding the fate of developing melanoma tumors and their ability to metastasize to certain preferred organ sites. Given their important role, they are a potential target for therapy against human melanoma.

CXCL8 receptor in melanoma therapy

Accumulating evidence suggests that CXCL8 is constitutively expressed in malignant melanoma and functions as an autocrine/paracrine growth, invasive and angiogenic factor [14,17,41,42]. Important roles of its cognate receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, have also been defined in melanoma progression [13]. Therefore, these multiple functional implications of CXCL8–CXCR1/CXCR2 signaling axis in melanoma pathogenesis underscore its importance as a target for cancer therapy. Antibodies to chemokines have shown some promise as a therapeutic modality for treatment of malignant melanoma. Earlier studies have demonstrated that neutralizing antibodies to CXCR1 and CXCR2 inhibit melanoma cell proliferation and invasive potential [17]. Humanized antibodies to CXCL8 have also been demonstrated to inhibit melanoma tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [43,44]. Neutralizing antibodies against other chemokines also demonstrate similar results, suggesting that melanoma may utilize different chemokine ligands to support growth [45]. Therefore, all these findings emphasize targeting CXCL8 receptors rather than CXCL8 alone. Also, it has been reported that 17β-estradiol, progesterone and dihydrotestosterone suppress the growth of melanoma by inhibiting CXCL8 production in a receptor-dependent manner [46]. Antagonists for CXCL8 receptors are also under consideration for melanoma therapy. Small molecule inhibitors with affinity for CXCR1, such as repertaxin, or those with affinity for CXCR2, such as SB-225002 or SB-332235, have been used to treat inflammatory diseases [47–49]. A recent study has demonstrated potential of the CXCR2/1 specific inhibitors, SCH-479833 and SCH-527123 in inhibiting human melanoma growth by decreasing tumor cell proliferation, survival and invasion [21]. Similarly, SCH-527123 has also been demonstrated to inhibit neutrophil recruitment, mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia in an animal model [50]. Thus, there is hope for utilizing these antagonists in future melanoma therapies.

Conclusion & future perspective

Despite decades of research, treatment of patients with advanced melanoma remains disappointing. This clearly indicates the pressing need for novel and effective therapeutic measures for restricting melanoma tumor growth and metastasis. The accumulating evidence resulting from the experimental studies points towards a critical role of CXCL8 and its receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, in melanoma progression and metastasis. A better understanding of the role of CXCL8 and its receptors in tumorigenesis, and metastasis, of melanoma may lead to novel approaches in its management and treatment. This also advocates that the measurement of CXCL8 and its receptors expression in melanoma samples has the potential of becoming a biomarker of relative tumor aggressiveness. An understanding of the mechanism(s) regulating activation of CXCR1 and/or CXCR2 in CXCL8-mediated modulation of melanoma metastasis will be important for prognostic measurements and designing effective strategies for the development of novel targeted molecular therapeutics.

Executive summary

Implications of CXCL8 and its receptors in melanoma biology

The expression of CXCL8 and its receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, in melanoma show a positive correlation with disease progression.

CXCL8 directly enhances endothelial cell proliferation, survival and matrix metalloproteinase expression in CXCR1- and CXCR2-expressing endothelial cells, indicating that it may be an important player in the process of angiogenesis.

CXCL8 and its receptors are implicated in melanoma progression and metastasis.

CXCL8 and its receptors as targets for melanoma therapy and disease management

CXCR2/1-specific small molecule inhibitors inhibited human melanoma growth by decreasing tumor cell proliferation, survival and invasion, which offers hope for utilizing these antagonists for future melanoma therapy.

Targeting CXCL8 using neutralizing antibodies also seems to be effective in inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis.

The aberrant expression and proven role of CXCL8 and its receptors in melanoma progression and metastasis advocates that their measurement in melanoma samples and/or patient’s blood has the potential to become a biomarker of tumor aggressiveness.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Seema Singh, Department of Oncologic Sciences, Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama, AL, USA.

Ajay P Singh, Department of Oncologic Sciences, Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama, AL, USA.

Bhawna Sharma, Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, NE, USA.

Laurie B Owen, Department of Oncologic Sciences, Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama, AL, USA.

Rakesh K Singh, Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 985900 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-5900, USA.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1. Richmond A, Yang J, Su Y. The good and the bad of chemokines/chemokine receptors in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22(2):175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00554.x. ▪▪ Interesting recent review with updates on chemokines receptors in melanoma.

- 2. Singh S, Sadanandam A, Singh RK. Chemokines in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(3–4):453–467. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9068-9. ▪ Highlights the roles of chemokines in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis.

- 3.Vandercappellen J, Van DJ, Struyf S. The role of CXC chemokines and their receptors in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):226–244. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richmond A, Lawson DH, Nixon DW, Chawla RK. Characterization of autostimulatory and transforming growth factors from human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45(12 Pt 1):6390–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richmond A, Balentien E, Thomas HG, et al. Molecular characterization and chromosomal mapping of melanoma growth stimulatory activity, a growth factor structurally related to β-thromboglobulin. EMBO J. 1988;7(7):2025–2033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuo Y, Raimondo M, Woodward TA, et al. CXC-chemokine/CXCR2 biological axis promotes angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;125(5):1027–1037. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature. 2007;445(7130):851–857. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varney ML, Johansson SL, Singh RK. Distinct expression of CXCL8 and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 and their association with vessel density and aggressiveness in malignant melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006;125(2):209–216. doi: 10.1309/VPL5-R3JR-7F1D-6V03. ▪ Highlights the relevance of CXCL8 and its receptors in malignant melanoma.

- 10.Singh RK, Varney ML, Bucana CD, Johansson SL. Expression of interleukin-8 in primary and metastatic malignant melanoma of the skin. Melanoma Res. 1999;9(4):383–387. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JM, Taraboletti G, Matsushima K, Van DJ, Mantovani A. Induction of haptotactic migration of melanoma cells by neutrophil activating protein/interleukin-8. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;169(1):165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cesare S, Marshall JC, Logan P, et al. Expression and migratory analysis of 5 human uveal melanoma cell lines for CXCL12, CXCL8, CXCL1, and HGF. J. Carcinog. 2007;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh S, Nannuru KC, Sadanandam A, Varney ML, Singh RK. CXCR1 and CXCR2 enhances human melanoma tumourigenesis, growth and invasion. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;100(10):1638–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605055. ▪▪ Interesting recent study defining the fuctional roles of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in melanoma progression.

- 14.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of interleukin 8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54(12):3242–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugurel S, Rappl G, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Increased serum concentration of angiogenic factors in malignant melanoma patients correlates with tumor progression and survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19(2):577–583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Viertel A, et al. Ultraviolet-B irradiation enhances melanoma cell motility via induction of autocrine interleukin 8 secretion. Exp. Dermatol. 2007;16(8):636–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varney ML, Li A, Dave BJ, Bucana CD, Johansson SL, Singh RK. Expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors in malignant melanoma with different metastatic potential and their role in interleukin-8 (CXCL-8)-mediated modulation of metastatic phenotype. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2003;20(8):723–731. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006814.48627.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh S, Varney M, Singh RK. Host CXCR2-dependent regulation of melanoma growth, angiogenesis, and experimental lung metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):411–415. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3378. ▪▪ Important study of CXCR2 knockout mice defining the host regulation of melanoma progression.

- 19.Salcedo R, Resau JH, Halverson D, et al. Differential expression and responsiveness of chemokine receptors (CXCR1-3) by human microvascular endothelial cells and umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2000;14(13):2055–2064. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0963com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li A, Varney ML, Valasek J, Godfrey M, Dave BJ, Singh RK. Autocrine role of interleukin-8 in induction of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, migration and MMP-2 production and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(1):63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-5208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh S, Sadanandam A, Nannuru KC, et al. Small-molecule antagonists for CXCR2 and CXCR1 inhibit human melanoma growth by decreasing tumor cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15(7):2380–2386. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Addison CL, Daniel TO, Burdick MD, et al. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J. Immunol. 2000;165(9):5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strieter RM, Belperio JA, Phillips RJ, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis of cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2004;14(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. J. Immunol. 2003;170(6):3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shono T, Ono M, Izumi H, et al. Involvement of the transcription factor NF-κB in tubular morphogenesis of human microvascular endothelial cells by oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16(8):4231–4239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luca M, Huang S, Gershenwald JE, Singh RK, Reich R, Bar-Eli M. Expression of interleukin-8 by human melanoma cells up-regulates MMP-2 activity and increases tumor growth and metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151(4):1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie K. Interleukin-8 and human cancer biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12(4):375–391. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giorgini S, Trisciuoglio D, Gabellini C, et al. Modulation of bcl-xL in tumor cells regulates angiogenesis through CXCL8 expression. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007;5(8):761–771. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangahas CR, Dela Cruz GV, Friedman-Jimenez G, Jamal S. Endothelin-1 induces CXCL1 and CXCL8 secretion in human melanoma cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125(2):307–311. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue K, Slaton JW, Eve BY, et al. Interleukin 8 expression regulates tumorigenicity and metastases in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):2104–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional contributors to tumor progression. Mol. Med. Today. 2000;6(4):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Hinsbergh VW, Koolwijk P. Endothelial sprouting and angiogenesis: matrix metalloproteinases in the lead. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;78(2):203–212. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin D, Galisteo R, Gutkind JS. CXCL8/IL8 stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression and the autocrine activation of VEGFR2 in endothelial cells by activating NF-κB through the CBM (Carma3/Bcl10/Malt1) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(10):6038–6042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800207200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proost P, Loos T, Mortier A, et al. Citrullination of CXCL8 by peptidylarginine deiminase alters receptor usage, prevents proteolysis, and dampens tissue inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205(9):2085–2097. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norgauer J, Metzner B, Schraufstatter I. Expression and growth-promoting function of the IL-8 receptor β in human melanoma cells. J. Immunol. 1996;156(3):1132–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh S, Sadanandam A, Varney ML, Nannuru KC, Singh RK. Small interfering RNA-mediated CXCR1 or CXCR2 knockdown inhibits melanoma tumor growth and invasion. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;126(2):328–336. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh RK, Gutman M, Reich R, Bar-Eli M. Ultraviolet B irradiation promotes tumorigenic and metastatic properties in primary cutaneous melanoma via induction of interleukin 8. Cancer Res. 1995;55(16):3669–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herlyn D, Iliopoulos D, Jensen PJ, et al. In vitro properties of human melanoma cells metastatic in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50(8):2296–2302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheibenbogen C, Mohler T, Haefele J, Hunstein W, Keilholz U. Serum interleukin-8 (IL-8) is elevated in patients with metastatic melanoma and correlates with tumour load. Melanoma Res. 1995;5(3):179–181. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hensley C, Spitzler S, McAlpine BE, et al. In vivo human melanoma cytokine production: inverse correlation of GM-CSF production with tumor depth. Exp. Dermatol. 1998;7(6):335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schadendorf D, Moller A, Algermissen B, Worm M, Sticherling M, Czarnetzki BM. IL-8 produced by human malignant melanoma cells in vitro is an essential autocrine growth factor. J. Immunol. 1993;151(5):2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh RK, Varney ML. Regulation of interleukin 8 expression in human malignant melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58(7):1532–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zigler M, Villares GJ, Lev DC, Melnikova VO, Bar-Eli M. Tumor immunotherapy in melanoma: strategies for overcoming mechanisms of resistance and escape. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2008;9(5):307–311. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00004. ▪ Important study of immunotherapy in melanoma.

- 44.Melnikova VO, Bar-Eli M. Bioimmunotherapy for melanoma using fully human antibodies targeting MCAM/MUC18 and IL-8. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19(5):395–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujisawa N, Hayashi S, Miller EJ. A synthetic peptide inhibitor for α-chemokines inhibits the tumour growth and pulmonary metastasis of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Melanoma Res. 1999;9(2):105–114. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanda N, Watanabe S. 17β-estradiol, progesterone, and dihydrotestosterone suppress the growth of human melanoma by inhibiting interleukin-8 production. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001;117(2):274–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertini R, Allegretti M, Bizzarri C, et al. Noncompetitive allosteric inhibitors of the inflammatory chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2: prevention of reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(32):11791–11796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White JR, Lee JM, Young PR, et al. Identification of a potent, selective non-peptide CXCR2 antagonist that inhibits interleukin-8-induced neutrophil migration. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(17):10095–10098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thatcher TH, McHugh NA, Egan RW, et al. Role of CXCR2 in cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005;289(2):L322–L328. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00039.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chapman RW, Minnicozzi M, Celly CS, et al. A novel, orally active CXCR1/2 receptor antagonist, Sch527123, inhibits neutrophil recruitment, mucus production, and goblet cell hyperplasia in animal models of pulmonary inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;322(2):486–493. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.119040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]