Abstract

The follicular phase of the ovine ovarian cycle demonstrates parallel increases in ovarian estrogens and uterine blood flow (UBF). Although estrogen and nitric oxide contribute to the rise in UBF, the signaling pathway remains unclear. We examined the relationship between the rise in UBF during the ovarian cycle of nonpregnant sheep and changes in the uterine vascular cGMP-dependent pathway and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa). Nonpregnant ewes (n = 19) were synchronized to either follicular or luteal phase using a vaginal progesterone-releasing device (CIDR), followed by intramuscular PGF2α, CIDR removal, and treatment with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin. UBF was measured with flow probes before tissue collection, and second-generation uterine artery segments were collected from nine follicular and seven luteal phase ewes. The pore-forming α- and regulatory β-subunits that constitute the BKCa, soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), and cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (cPKG) isoforms (cPKG1α and cPKG1β) were measured by Western analysis and cGMP levels by RIA. BKCa subunits were localized by immunohistochemistry. UBF rose >3-fold (P < 0.04) in follicular phase ewes, paralleling a 2.3-fold rise in smooth muscle cGMP and 32% increase in cPKG1α (P < 0.05). sGC, cPKG1β, and the BKCa α-subunit were unchanged. Notably, expression of β1- and β2-regulatory subunits rose 51 and 79% (P ≤ 0.05), respectively. Increases in endogenous ovarian estrogens in follicular-phase ewes result in increases in UBF associated with upregulation of the cGMP- and cPKG-dependent pathway and increased vascular BKCa β/α-subunit stoichiometry, suggesting enhanced BKCa activation contributes to the follicular phase rise in UBF.

Keywords: estrogen, uterine blood flow, protein kinase G, guanylyl cyclase

uterine blood flow (UBF) increases during the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle and throughout pregnancy (7, 9, 11, 28, 35). Although the mechanisms responsible for these increases in UBF are incompletely understood, both are associated with increases in circulating endogenous estrogens of ovarian and placental origin, respectively, and the estrogen-to-progesterone ratio (E/P), suggesting similar mechanisms may be involved (1, 9, 18, 20, 35, 43). Acute and chronic exogenous estrogen increase UBF in nonpregnant and pregnant sheep and other species (28). Markee (22) demonstrated that the uterine hyperemia in the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle was reproducible after administration of ovarian estrogens. Subsequently, estradiol-17β (E2β) was shown to be a potent uterine vasodilator when infused either systemically or directly in the uterine circulation, increasing UBF >10-fold within 90–120 min (15, 19, 28, 32, 34). This was reproducible every 24 h and characterized by a 30-min delay followed by a peak and plateau at 90–120 min and a gradual decline over 8–12 h (15). The delay in the acute rise in UBF after E2β has been shown to reflect upregulation and activation of uterine artery nitric oxide synthase (NOS) followed by enhanced nitric oxide (NO) synthesis and its downstream effects on cGMP (31, 39, 48, 50). Of note, ovarian estrogens and local NO synthesis also contribute to the rise in UBF in the follicular phase of the ovine ovarian cycle (9, 18, 21, 43); however, the steps in this cascade are unclear.

The large-conductance, voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel (BKCa) is a heterotetramer of its pore-forming α-subunit encoded by slo1 gene and one or more isoforms of tissue specific regulatory β-subunits (8). It is ubiquitously expressed among excitable and nonexcitable mammalian tissues, including neurons and myocytes (3). Its open state probability is increased by membrane depolarization or increases in cytosolic Ca2+ (14). Depending on the cell type, BKCa activity may differ in Ca2+ sensitivity and macroscopic kinetics. Enhanced BKCa activity in smooth muscle cells (SMC) produces membrane hyperpolarization, inhibits Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels, decreases cytosolic Ca2+, and consequently produces SMC relaxation (17). BKCa has substantial functional diversity stemming from alternative splicing of the α-subunit, interaction with an array of regulatory β-subunits, and metabolic regulation, including phosphorylation by protein kinases (3, 17, 24, 40). Several variants of the β-subunit exist, but β1- and β2-subunits are specific to SMC (24, 40). Altered β/α stoichiometry through increases in the β1-subunit enhances Ca2+ and voltage sensitivity (24). In nonpregnant and pregnant ewes, BKCa contribute to acute E2β-mediated increases in UBF (30, 37), as well as the effects of prolonged E2β exposure on baseline UBF in ovariectomized nonpregnant sheep and baseline uteroplacental blood flow in ovine pregnancy (23, 36). Moreover, prolonged E2β exposure upregulates β1-subunit expression, altering channel stoichiometry and sensitivity (23, 39). The role of BKCa in the rise in UBF during the ovarian cycle and increases in endogenous ovarian estrogens has not been studied.

In the present report, we studied uterine arteries obtained from nonpregnant ewes synchronized into the follicular or luteal phases of the ovarian cycle (9). In this model, there is evidence of endogenous estrogen-mediated increases in uterine artery NO, resulting in the rise in UBF during the follicular phase (9, 18, 21, 43). Therefore, we sought to determine if the rise in UBF was related to alterations in the NO-cGMP-protein kinase G pathway as well as BKCa expression and stoichiometry.

METHODS

Animal preparation and experimental protocol.

Tissues obtained from 19 nonpregnant, intact multiparous ewes (50–65 kg) of mixed Western breed were used in the present studies. Animals were studied between September and May; those studied between September and March had evidence of estrous cycles, whereas those studied April to May previously exhibited cycles. Animals were randomly assigned to either follicular (n = 10) or luteal (n = 9) phases of the ovarian cycle; all were implanted with a vaginal progesterone (P4)-controlled internal drug-releasing device (CIDR, 0.3 g; Latinagro de Mexico, Monterrey, Mexico) to clamp systemic P4 levels at luteal phase values (9, 43). After at least 7 days of P4 treatment, ewes received two 7.5-mg im injections of PGF2α (Dinoprost Tromethamine-Lutalyse; Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) 4 h apart to lyse existing corpora lutea. On the 10th day following CIDR placement, the CIDR was removed, and each animal received one dose of 500 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin intramuscularly. This regimen causes a rapid fall in P4; a rise in plasma estrogens and the estrogen-to-P4 ratio (E/P), with levels peaking at 36–48 h; a surge in luteinizing hormone; and ovulation within 48–56 h (9, 43). The above procedures were performed at the breeding farm under natural lighting conditions, and animals were transported to the laboratory before termination where similar lighting conditions were maintained. Follicular phase ewes were studied ∼48 h (±30 min) after CIDR removal, designated as day 0 of the ovarian cycle. Luteal phase ewes were studied 12–13 days after CIDR removal, designated as day 10–11 of the cycle. Ovaries were collected from all animals at the time of termination and mapped to confirm the status within the cycle (Table 1). Ovaries from follicular phase ewes had more total follicles and large follicles 4–6 mm than luteal phase ovaries as well as avascular regressing corpora luteum (CL) vs. large vascular CL in luteal phase ewes. Measurements of P4 in jugular venous blood were available in four follicular (0.5 ± 0.2 ng/ml) and two luteal (5.6 and 6.8 ng/ml) phase animals, demonstrating an ∼10-fold rise in circulating P4 in the latter (P < 0.025). More detailed values for E2β, P4 and, the E/P have been reported (9, 43).

Table 1.

Ovarian structures in nonpregnant ewes synchronized into either the follicular or luteal phases of the ovarian cycle as described in methods

| Diameter, mm | Follicular Phase (n = 9) | Luteal Phase (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|

| Corpora lutea | 6.9±0.6(avascular)* | 10.1±0.3(vascular) |

| Medium follicles (3–5 mm) | 3.8±0.2(28) | 4.0±0.3(8) |

| Large follicles (≥6 mm) | 8.2±0.4(14)* | 6.9±0.6(4) |

Values are means ± SE for the no. of specific ovarian structures for all ovaries from each ewe; n, no. of ewes in each group. The total no. of structures is in parentheses.

P < 0.05 by nonpaired t-test.

On the day of study, a percutaneous jugular venous catheter was inserted for intravenous administration of ketamine (10 mg/ml) in 0.9% saline and 5% dextrose with supplemental pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal; 50 mg/ml) as needed for surgical anesthesia as previously described (9, 43). The abdomen was shaved and aseptically scrubbed, following which, the uterus was exposed through a midventral laparotomy, and Transonic flow probes (3–4 mm ID; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) were placed around the middle uterine artery of each uterine horn. UBF in each uterine horn was recorded for 4–6 min after stabilization. Animals were then killed with intravenous pentobarbital sodium (75 mg/kg), and tissues were collected rapidly. Animal handling and protocols for these experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Research and Animal Care and Use Committees of both the Medical School and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Tissue preparation.

The intact uterus was removed in block, and second-generation uterine arteries were dissected from both uterine horns and placed in sterile chilled physiological saline solution; the adventitia and intraluminal blood were removed. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the time of assay (21, 29, 39). Additional uterine artery samples were prepared for immunohistochemistry as described below. Tissues from both groups of animals were used in other studies; therefore, samples were not available from each animal for each assay, resulting in a difference in the n values noted in the results.

Western immunoblots.

Samples of second-generation uterine arteries (30 mg) were weighed and homogenized in 40× volumes of SDS buffer as previously described (23, 29, 33, 38). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 2 min, the supernatant was removed, and an aliquot from each animal was used to measure cellular or soluble protein by bicinchoninic acid reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as previously reported (23, 33, 38). Bromphenol blue and 2-mercaptoethanol were added to the aliquots representing each animal studied, and equal amounts of soluble protein were loaded (20 μg) on a single 7.5–10% polyacrylamide minigel and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to nitrocellulose paper at 100 volts for 1 h (23, 29, 33, 38). Running all samples on a single gel takes into account differences in protein transfer; because similar amounts of soluble protein are loaded, comparisons can be made between samples. The immunoblots were incubated overnight with antisera to BKCa α-subunit (1:300; AB5228–200UL; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), β1-subunit (1:400; ab3587, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), β2-subunit (1:200; APC-034; Alomane Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC; 1:1,000; G 4405; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), cGMP-dependent protein kinase G1α (cPKG1α; 1:1,000; PK10; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or cPKG1β (1:750; a gift from HK Surks, Tufts-New England Medical Center). To determine what protein could be used as a loading control, we performed preliminary studies in which we measured uterine artery smooth muscle actin contents. These studies demonstrated that actin was unaffected (P > 0.1; data not shown) after 7 days of daily E2β exposure (1 μg/kg iv) in nonpregnant castrated ewes; thus, we chose to use α-actin as a loading control (1:8,000; monoclonal anti-α actin; Sigma) on immunoblots performed with cPKG1α and the BKCa β1-subunit in luteal (n = 4) and follicular (n = 4) phase arteries and reprobed for α-actin at 42 kDa. There was no difference in α-actin on either immunoblot (P > 0.8; Fig. 1). The repeat immunoblots performed to demonstrate equal loading plus the two proteins of interest are available as Supplemental Fig. 1 (Supplemental data for this article can be found on the American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism website.). After 1 h of incubation with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000), immunoreactive protein was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Samples were compared by scanning densitometry in arbitrary units (TotalLab Software Package; Biosystematica, Wales, UK) as reported (23, 29, 33, 38). Ovine cerebellum served as a positive internal control for BKCa α-subunit.

Fig. 1.

Representative immunoblot for the 42-kDa protein α-actin that served as a loading control for studies of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (cPKG1α) and the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (BKCa) β1-subunit. There were no differences between luteal (n = 4) and follicular (n = 4) phase uterine arteries, P > 0.8 by nonpaired t-test on each immunoblot. Supplemental Fig. 1 shows the relationship with the proteins of interest.

Measurement of cGMP.

The cGMP content of uterine arteries harvested from follicular and luteal phase animals was measured by radioimmunoassay (cGMP [125I] RIA KIT; NEX-133; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) as previously reported (33, 39). Briefly, 50 mg of frozen uterine artery were homogenized in 1 ml of 6% TCA and centrifuged at 3,000 g to remove bulk proteins. TCA was added to the homogenate and extracted from the supernatant with water-saturated dimethyl-ether three times. The supernatant was precipitated by lyophilization, dissolved in 0.05 M sodium acetate, and used in the assay. All samples were measured in a single assay.

Immunohistochemistry.

At the time of tissue collection, intact segments of second-generation uterine arteries were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 h at room temperature, and subsequently embedded in paraffin as previously described (29, 39). Sections were mounted on slides, deparaffinized, hydrated, incubated with avidin-biotin blocking agent for 30 min, and incubated overnight at room temperature with polyclonal antibodies to the BKCa α-, β1-, or β2-subunits (1:30). After endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% H2O2 in H2O for 30 min, immunostaining was detected with standard strepavidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase and hematoxylin counterstaining. Samples were randomly selected from three follicular and three luteal phase animals and embedded in a single block. Nonimmune rabbit serum was used to show antibody specificity.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between follicular and luteal phase measurements were determined with Student's nonpaired t-test. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

UBF.

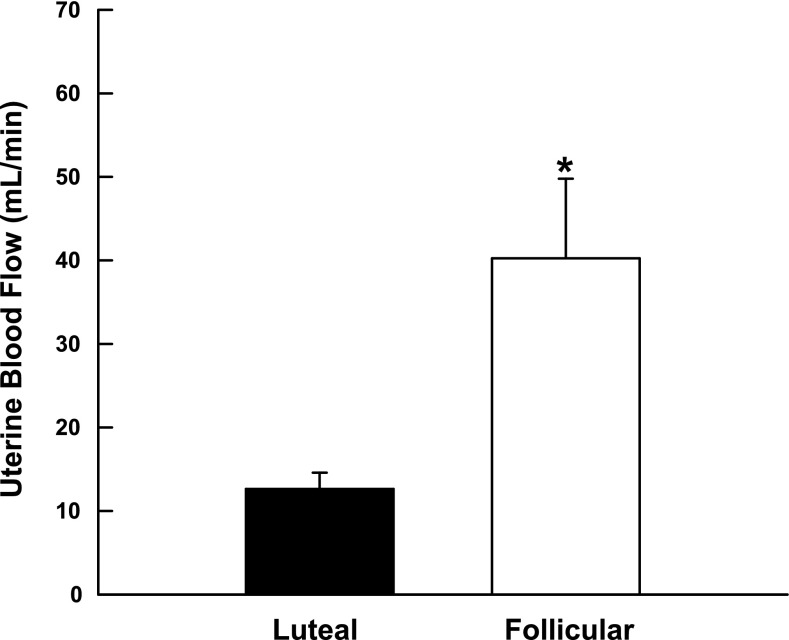

UBF measurements did not differ in the two uterine horns (P > 0.1); therefore, we used the average of the two values for each ewe. UBF was 3.2-fold higher in the follicular phase animals (n = 5) at the time of tissue collection compared with those allowed to progress to the luteal phase (n = 3) (Fig. 2; P < 0.04).

Fig. 2.

Change in basal uterine blood flow during the luteal and follicular phases of the ovine ovarian cycle. Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.04, nonpaired t-test.

Signaling pathway.

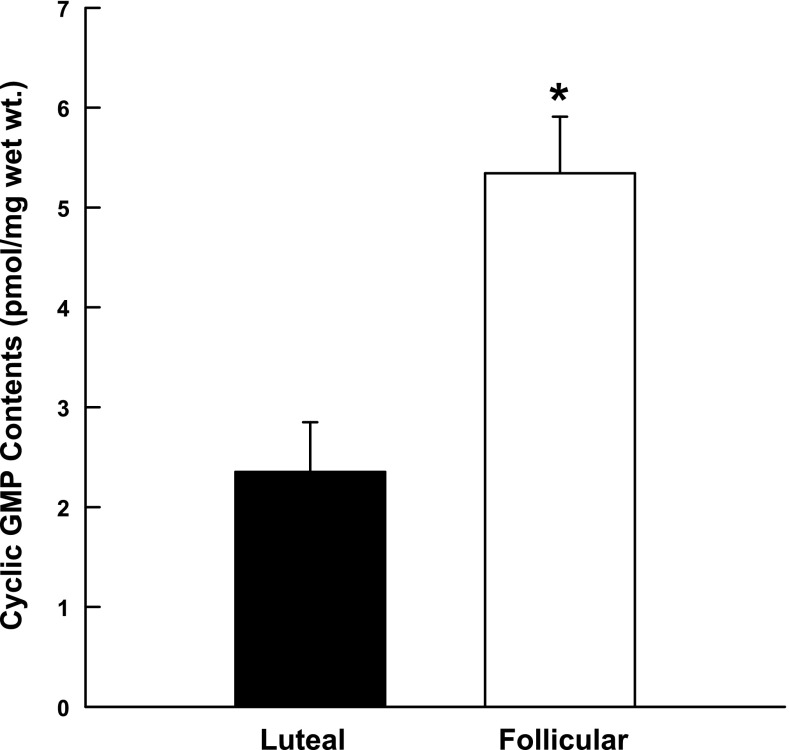

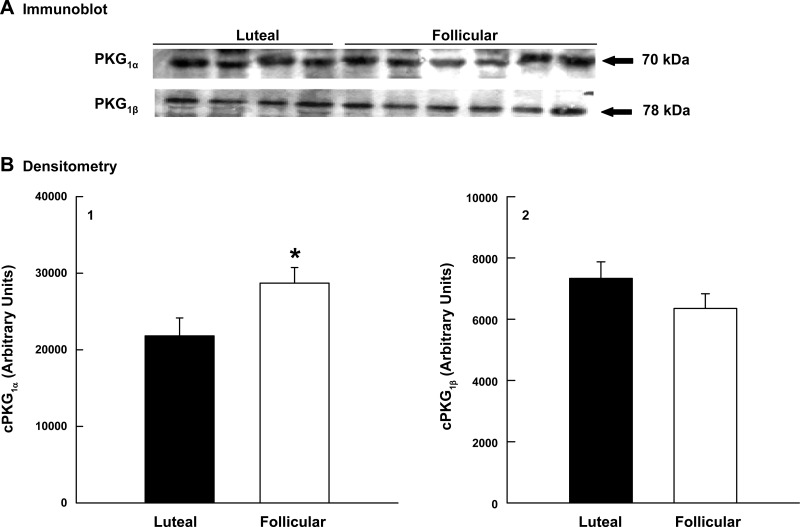

sGC was detected in all samples of uterine artery smooth muscle examined, but there were no differences in protein expression in the follicular and luteal phases of the ovarian cycle (P = 0.9, data not shown). In contrast, uterine arteries obtained from follicular phase ewes had cGMP contents 2.3-fold greater than vessels collected from luteal phase ewes (P < 0.02; Fig. 3). To further define the NO-cGMP-cPKG pathway, we examined cPKG1 isoform expression using immunoblot analysis. cPKG1β expression did not differ in follicular and luteal phase uterine arteries (P = 0.22; Fig. 4B2); however, cPKG1α protein was 32% higher in follicular vs. luteal phase tissues (P = 0.047; Fig. 4B1). In the secondary analysis to assess protein loading, there was no difference in α-actin (P = 0.9), but cPKG1α increased 21% (P = 0.008; see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of cGMP contents in luteal (n = 3) and follicular (n = 3) phase uterine arteries during the ovine ovarian cycle. Data are means ± SE; *P < 0.02, nonpaired t-test.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the ovarian cycle on cPKG1α and cPKG1β expression in uterine arteries from luteal (n = 4) and follicular (n = 6) phase sheep. A: immunoblot analyses. B: densitometry in arbitrary units from the immunoblots for cPKG1α (B1) and cPKG1β (B2). Data are means ± SE; *P = 0.047, nonpaired t-test.

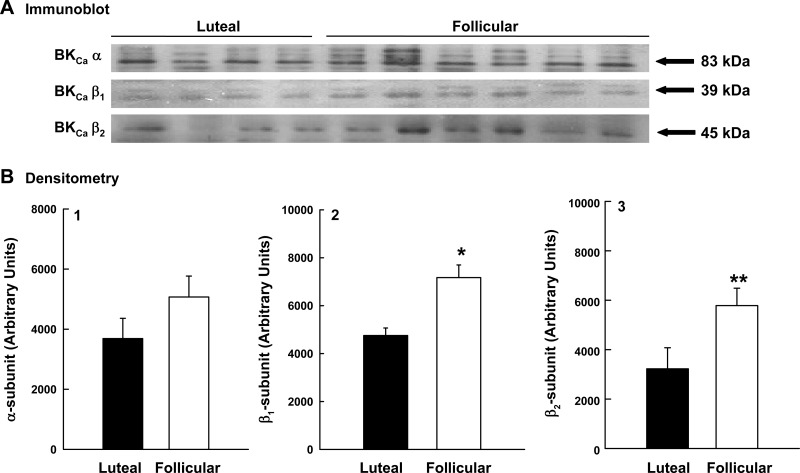

BKCa expression.

The density of BKCa channels is determined by measuring the expression of the pore-forming α-subunit (17, 23, 33, 38). There was no difference in α-subunit protein in uterine artery smooth muscle from follicular and luteal phase ewes (P = 0.2; Fig. 5B1). In contrast, β1- and β2-subunit protein expression was 51% (P = 0.009) and 79% (P = 0.05), respectively, greater in arteries obtained from follicular phase animals vs. luteal phase ewes (Fig. 5, B2 and B3). As above, α-actin did not differ in luteal (n = 4) and follicular (n = 4) phase arteries (P = 0.8), and β1-subunit increased 37% (P = 0.1; see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 5.

Effect of the ovarian cycle on BKCa subunit expression in the uterine artery during the luteal (n = 4) and follicular (n = 6) phases. A: immunoblot analyses for α-, β1-, and β2-subunits. B: densitometry in arbitrary units from the immunoblots for α (B1)-, β1 (B2)-, and β2 (B3)-subunits. Data are means ± SE; *P = 0.009 and **P = 0.05, nonpaired t-test.

Immunohistochemistry.

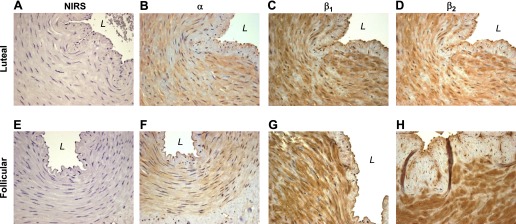

To determine the tissue localization of the α- and β-subunits comprising the BKCa channel within the intact uterine artery and to further assess the pattern of expression during the ovarian cycle, we performed immunohistochemistry on randomly selected samples of uterine arteries from three follicular and three luteal phase animals. Nonimmune rabbit serum did not show immunostaining in any vessel examined (Fig. 6, A and E). Although α-subunit immunostaining was observed throughout the uterine smooth muscle in each sample examined, this was not seen in the endothelium of either follicular or luteal phase arteries (Fig. 6, B and F). There also was diffuse immunostaining for the regulatory β1- and β2-subunits in the smooth muscle of all arteries assessed, but not in the endothelium. Although densitometric measurements were not made, β1 (Fig. 6G)- and β2 (Fig. 6H)-subunit immunostaining appears to be greater than α-subunit immunostaining in the media of follicular phase uterine arteries.

Fig. 6.

Representative immunohistochemistry of BKCa α-, β1-, and β2-subunits in randomly selected uterine arteries during the luteal (A–D) and follicular (E–H) phases of the ovine ovarian cycle. Figures are at ×40 magnification. NIRS, control nonimmune rabbit serum; L, vessel lumen.

DISCUSSION

Propagation of any species depends on the successful progression through each portion of the reproductive cycle, which in eutherian mammals includes the ovarian cycle, implantation or attachment, placentation, and growth of the maternal uteroplacental and fetal umbilicoplacental vascular beds (28). UBF changes during the reproductive cycle and is responsible for maintaining uterine and placental oxygen and nutrient delivery (28). Although our understanding of UBF regulation in pregnancy has expanded, only modest attention has been given to its regulation in the ovarian cycle and, in particular, the rise in UBF in the follicular phase when the uterus is being prepared for implantation (7, 11, 26). This rise is believed to reflect receptor-mediated actions of ovarian estrogens and local NOS activation (9, 18, 21); however, the remainder of the signaling pathway is incompletely described. In the present study, the rise in UBF in follicular phase ewes was paralleled by upregulation of the cGMP-cPKG pathway and increases in expression of β-regulatory subunits of the BKCa channel, which contributes to E2β-mediated uterine vasodilation and the maintenance of uteroplacental blood flow in pregnancy (23, 30, 33, 36, 37). Thus we now provide evidence that the rise in endogenous ovarian estrogens and UBF in follicular phase ewes, previously shown to be associated with activation of vascular NOS (9, 18, 21), is also associated with upregulation of the cGMP-PKG pathway and BKCa.

UBF increases in follicular phase ewes and is associated with increased circulating levels of ovarian estrogens, potent uterine vasodilators, and an elevated E/P (9, 20, 27, 28, 43). During the luteal phase of the cycle, UBF falls, paralleling decreases in the E/P ratio and predominance of P4, which attenuates estrogen-mediated vasodilation (10, 12, 27, 28). Studies of the interaction of these endocrine changes and UBF in sheep have been difficult because of the seasonality of the cycle and variability in the cyclical pattern of ovarian hormones and UBF (6, 7, 9, 11, 27). Gibson et al. (9) developed a chronic ovine model that allows the study of these interactions independent of the season. They observed a fivefold rise in UBF during the follicular phase that paralleled increases in plasma estrogens and the E/P. In the luteal phase, UBF fell in concert with decreases in the E/P and increases in P4. Sprague et al. (43) reported similar observations using this model. In our study, UBF also rose three- to fivefold in follicular phase ewes and was associated with low P4 values. The rise in UBF is also associated with activation of an estrogen- and NO-mediated pathway, since the estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist ICI-182,780 and the NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester attenuate the rise in UBF (9, 18, 21). Similar changes occur in ovariectomized nonpregnant ewes after exposure to exogenous E2β (18, 29, 31, 39, 48, 50), demonstrating that responses to endogenous and exogenous estrogens are very similar. However, ER and NOS inhibition only partially decrease UBF in follicular phase ewes; thus, alternative pathways may also contribute to the rise in UBF. These pathways are unclear as are the changes in vascular cGMP and other aspects of the cascade that contribute to NO-mediated increases in UBF.

E2β enhances type I and III NOS expression in uterine arteries from nonpregnant ewes, and this is associated with increased cGMP synthesis and uterine vasodilation (29, 31, 39, 48, 50). Although NO contributes to the rise in follicular phase UBF (9), it is unclear if guanylyl cyclase and cGMP are altered. Using the model of Gibson et al. (9), we observed equal fold increases in UBF and uterine artery cGMP in follicular phase animals. However, sGC was unchanged, suggesting enzyme activity increases after exposure to endogenous estrogen. Similar changes are also seen in uterine arteries from late pregnant ewes, which are exposed to endogenous estrogens of placental origin (33). Although endothelial NOS mRNA and protein increase in follicular phase uterine arteries (21, 48), type 1 NOS has not been examined. This is of interest, since daily E2β increases type I NOS in uterine arteries of ovariectomized ewes (29, 39). Moreover, we have seen increases in uterine artery type I NOS during ovine pregnancy (Rosenfeld, unpublished observations). Future studies should address this.

Smooth muscle contraction and relaxation are regulated by the relative rates of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent MLC kinase and dephosphorylation by myosin phosphatase (5, 13, 42). The NO-cGMP pathway activates relaxation via cPKG and Ca2+-dependent and -independent mechanisms (44). The former involves decreases in intracellular Ca2+ and the latter activation of MLC phosphatase, which dephosphorylates MLC resulting in SMC relaxation (44, 46). Two cPKG isoforms, cPKG1 and cPKG2, exist (25, 44); however, cPKG1, expressed as cPKG1α and cPKG1β, predominates in SMC (46). Both cPKG1 isoforms are coexpressed in SMC, but their relative levels and specific roles are poorly understood (44, 45). Both modify intracellular Ca2+, whereas cPKG1α also activates MLC phosphatase (44). Notably, the sensitivity of cPKG1α to cGMP is 10-fold greater than cPKG1β (2). We found both isoforms in uterine artery SMC, but only cPKG1α increased in the follicular phase, suggesting endogenous estrogens selectively increase transcription and/or translation. Similar changes are seen in uterine arteries from pregnant sheep, which are exposed to increases in endogenous placental estrogens (1, 33). If cPKG1α is selectively upregulated by estrogen and is 10-fold more sensitive to cGMP than cPKG1β, amplification of the NO-cGMP-cPKG pathway is likely to occur after estrogen exposure. This will need to be examined, as well as the mechanisms that regulate cPKG1α during the reproductive cycle.

BKCa contribute to the vasodilatory effects of exogenous estrogens via the NO-cGMP-cPKG pathway (4, 16, 37, 51) and/or directly through β1-subunit activation (49). β1- and β2-regulatory subunits regulate Ca2+ and voltage sensitivity and modify BKCa activation kinetics (41, 47). The pore-forming α-subunit and both SMC specific β-regulatory subunits were present in uterine artery SMC of cycling nonpregnant sheep, confirming observations in nonpregnant women and ovariectomized nonpregnant and intact pregnant sheep (23, 30, 33, 38). Channel density was unchanged during the ovarian cycle, but β-subunit expression increased at the time of maximum UBF, thereby increasing β/α stoichiometry. Similar alterations occur in E2β-treated nonpregnant castrated ewes in whom basal UBF increases and responses to acute E2β exposure are enhanced (23, 39). The change in BKCa stoichiometry occurred in concert with increases in uterine vascular NOS expression (29, 31, 39, 48, 50) and cGMP synthesis. Thus upregulation of the NO-cGMP-cPKG pathway in the follicular phase could enhance BKCa phosphorylation and activation, resulting in uterine vasodilation. It is notable that nonspecific ER and NOS inhibition do not completely reverse the rise in follicular phase UBF (9, 18). Thus estrogen might also directly activate BKCa via the β1-subunit and contribute to the rise in UBF (37). The role of P4 in the luteal phase reversal of UBF and attenuation of the NO-cGMP-cPKG-BKCa pathway requires further study.

This is the first report showing that increases in endogenous estrogens during the follicular phase of the ovine ovarian cycle contribute to changes in uterine artery BKCa expression and possibly function by increasing β/α stoichiometry and thus channel sensitivity and kinetics without altering channel density. This is paralleled by increased uterine artery cGMP contents and cPKG1α expression; thus, the entire NO-cGMP-cPKG-BKCa pathway is upregulated by endogenous estrogen. It is unclear how each segment of the pathway is regulated and if the concertmaster is indeed estrogen or the E/P. If BKCa regulate uterine vascular tone during the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle and if increases in β/α stoichiometry modify channel function, the BKCa may be a pharmacologic target in conditions associated with impaired uterine vascular function, e.g., diabetes and chronic hypertension.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-008783 (C. R. Rosenfeld), HL-49210 (R. R. Magness), and HL87144 (R. R. Magness) and the George L. MacGregor Professorship in Pediatrics (C. R. Rosenfeld).

DISCLOSURES

There are no known conflicts of interest or disclosures regarding these studies.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Carnegie JA, Robertson HA. Conjugated and unconjugated estrogens in fetal and maternal fluids of the pregnant ewe: a possible role for estrone sulfate during early pregnancy. Biol Reprod 19: 202–211, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang S, Hypolite JA, Velez M, Changolkar A, Wein AJ, Chacko S, DiSanto ME. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-1 activity in the corpus cavernosum smooth muscle of diabetic rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R950–R960, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen L, Shipston MJ. Cloning of potassium channel splice variants from tissues and cells. Methods Mol Biol 491: 35–60, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darkow DJ, Lu L, White RE. Estrogen relaxation of coronary artery smooth muscle is mediated by nitric oxide and cGMP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H2765–H2773, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev 79: 387–423, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ford SP. Control of uterine and ovarian blood flow throughout the estrous cycle and pregnancy of ewes, sows and cows. J Anim Sci 55, Suppl 2: 32–42, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford SP, Christenson RK, Chenault JR. Patterns of blood flow to the uterus and ovaries of ewes during the period of luteal regression. J Anim Sci 49: 1510–1516, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghatta S, Nimmagadda D, Xu X, O'Rourke ST. Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol Ther 110: 103–116, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gibson TC, Phernetton TM, Wiltbank MC, Magness RR. Development and use of an ovarian synchronization model to study the effects of endogenous estrogen and nitric oxide on uterine blood flow during ovarian cycles in sheep. Biol Reprod 70: 1886–1894, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Greiss FC, Jr, Anderson SG. Effect of ovarian hormones on the uterine vascular bed. Am J Obstet Gynecol 107: 829–836, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greiss FC, Jr, Anderson SG. Uterine vascular changes during the ovarian cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 103: 629–640, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hansel W, Convey EM. Physiology of the estrous cycle. J Anim Sci 57, Suppl 2: 404–424, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hartshorne DJ, Hirano K. Interactions of protein phosphatase type 1, with a focus on myosin phosphatase. Mol Cell Biochem 190: 79–84, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horrigan FT, Aldrich RW. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol 120: 267–305, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Killam AP, Rosenfeld CR, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Effect of estrogens on the uterine blood flow of oophorectomized ewes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 115: 1045–1052, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ko EA, Han J, Jung ID, Park WS. Physiological roles of K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Smooth Muscle Res 44: 65–81, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 69–78, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magness RR, Phernetton TM, Gibson TC, Chen DB. Uterine blood flow responses to ICI 182,780 in ovariectomized oestradiol-17β-treated, intact follicular and pregnant sheep. J Physiol 565: 71–83, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR. Local and systemic estradiol-17β: effects on uterine and systemic vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 256: E536–E542, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR, Carr BR. Protein kinase C in uterine and systemic arteries during ovarian cycle and pregnancy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 260: E464–E470, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Magness RR, Sullivan JA, Li Y, Phernetton TM, Bird IM. Endothelial vasodilator production by uterine and systemic arteries. VI. Ovarian and pregnancy effects on eNOS and NO(x). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1692–H1698, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Markee JE. Rhythmic vascular uterine changes. Am J Physiol 100: 32–29, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nagar D, Liu XT, Rosenfeld CR. Estrogen regulates β1-subunit expression in Ca2+-activated K+ channels in arteries from reproductive tissues. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1417–H1427, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orio P, Rojas P, Ferreira G, Latorre R. New disguises for an old channel: MaxiK channel β-subunits. News Physiol Sci 17: 156–161, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orstavik S, Natarajan V, Tasken K, Jahnsen T, Sandberg M. Characterization of the human gene encoding the type 1α and type 1β cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PRKG1). Genomics 42: 311–318, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reynolds LP, Magness RR, Ford SP. Uterine blood flow during early pregnancy in ewes: interaction between the conceptus and the ovary bearing the corpus luteum. J Anim Sci 58: 423–429, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roman-Ponce H, Caton D, Thatcher WW, Lehrer R. Uterine blood flow in relation to endogenous hormones during estrous cycle and early pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 245: R843–R849, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosenfeld CR. The Uterine Circulation. Ithaca, NY: Perinatology, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosenfeld CR, Chen C, Roy T, Liu X. Estrogen selectively up-regulates eNOS and nNOS in reproductive arteries by transcriptional mechanisms. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10: 205–215, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rosenfeld CR, Cornfield DN, Roy T. Ca2+-activated K+ channels modulate basal and E2β-induced rises in uterine blood flow in ovine pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H422–H431, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosenfeld CR, Cox BE, Roy T, Magness RR. Nitric oxide contributes to estrogen-induced vasodilation of the ovine uterine circulation. J Clin Invest 98: 2158–2166, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenfeld CR, Killam AP, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Effect of estradiol-17β, on the magnitude and distribution of uterine blood flow in nonpregnant, oophorectomized ewes. Pediatr Res 7: 139–148, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenfeld CR, Liu X. Pregnancy modifies large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel expression and cGMP-dependent signaling in uterine vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1878–H1887, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosenfeld CR, Morriss FH, Jr, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Effect of estradiol-17β on blood flow to reproductive and nonreproductive tissues in pregnant ewes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 124: 618–629, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosenfeld CR, Morriss FH, Jr, Makowski EL, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Circulatory changes in the reproductive tissues of ewes during pregnancy. Gynecol Invest 5: 252–268, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosenfeld CR, Roy T, DeSpain K, Cox BE. Large-conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels regulate basal uteroplacental blood flow in ovine pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig 12: 402–408, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosenfeld CR, White RE, Roy T, Cox BE. Calcium-activated potassium channels and nitric oxide coregulate estrogen-induced vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H319–H328, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosenfeld CR, Word RA, DeSpain K, Liu XT. Large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels contribute to vascular function in nonpregnant human uterine arteries. Reprod Sci 15: 651–660, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salhab WA, Shaul PW, Cox BE, Rosenfeld CR. Regulation of types I and III NOS in ovine uterine arteries by daily and acute estrogen exposure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H2134–H2142, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 921–931, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Savalli N, Kondratiev A, de Quintana SB, Toro L, Olcese R. Modes of operation of the BKCa channel β2 subunit. J Gen Physiol 130: 117–131, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature 372: 231–236, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sprague BJ, Phernetton TM, Magness RR, Chesler NC. The effects of ovarian cycle and pregnancy on uterine vascular impedance and uterine artery mechanics. Europ J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bio 144: S184–S191, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Surks HK. cGMP-dependent protein kinase 1 and smooth muscle relaxation: a tale of two isoforms. Circ Res 101: 1078–1080, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tamura N, Itoh H, Ogawa Y, Nakagawa O, Harada M, Chun TH, Suga S, Yoshimasa T, Nakao K. cDNA cloning and gene expression of human type 1α cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Hypertension 27: 552–557, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tang KM, Wang GR, Lu P, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Heximer SP, Kaltenbronn KM, Blumer KJ, Siderovski DP, Zhu Y, Mendelsohn ME. Regulator of G-protein signaling-2 mediates vascular smooth muscle relaxation and blood pressure. Nat Med 9: 1506–1512, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Torres YP, Morera FJ, Carvacho I, Latorre R. A marriage of convenience: β-subunits and voltage-dependent K+ channels. J Biol Chem 282: 24485–24489, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vagnoni KE, Shaw CE, Phernetton TM, Meglin BM, Bird IM, Magness RR. Endothelial vasodilator production by uterine and systemic arteries. III. Ovarian and estrogen effects on NO synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H1845–H1856, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Valverde MA, Rojas P, Amigo J, Cosmelli D, Orio P, Bahamonde MI, Mann GE, Vergara C, Latorre R. Acute activation of Maxi-K channels (hSlo) by estradiol binding to the β subunit. Science 285: 1929–1931, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Van Buren GA, Yang DS, Clark KE. Estrogen-induced uterine vasodilatation is antagonized by l-nitroarginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167: 828–833, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. White RE, Darkow DJ, Lang JL. Estrogen relaxes coronary arteries by opening BKCa channels through a cGMP-dependent mechanism. Circ Res 77: 936–942, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.