Abstract

Ca+ sparklets are subcellular Ca2+ signals produced by the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs). In cerebral arterial myocytes, Ca2+ sparklet activity varies regionally, resulting in low and high activity, “persistent” Ca2+ sparklet sites. Although increased Ca2+ influx via LTCCs in arterial myocytes has been implicated in the chain of events contributing to vascular dysfunction during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes, the mechanisms underlying these pathological changes remain unclear. Here, we tested the hypothesis that increased Ca2+ sparklet activity contributes to higher Ca2+ influx in cerebral artery smooth muscle during acute hyperglycemia and in an animal model of non-insulin-dependent, type 2 diabetes: the dB/dB mouse. Consistent with this hypothesis, acute elevation of extracellular glucose from 10 to 20 mM increased the density of low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklet sites as well as the amplitude of LTCC currents in wild-type cerebral arterial myocytes. Furthermore, Ca2+ sparklet activity and LTCC currents were higher in dB/dB than in control myocytes. We found that activation of PKA contributed to higher Ca2+ sparklet activity during hyperglycemia and diabetes. In addition, we found that the interaction between PKA and the scaffolding protein A-kinase anchoring protein was critical for the activation of persistent Ca2+ sparklets by PKA in cerebral arterial myocytes after hyperglycemia. Accordingly, PKA inhibition equalized Ca2+ sparklet activity between dB/dB and wild-type cells. These findings suggest that hyperglycemia increases Ca2+ influx by increasing Ca2+ sparklet activity via a PKA-dependent pathway in cerebral arterial myocytes and contributes to vascular dysfunction during diabetes.

Keywords: sparklets, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, protein kinase A

diabetes is associated with an increase in vascular tone that contributes to a higher propensity for developing multiple pathological conditions including hypertension, stroke, renal failure, coronary artery disease, and retinal degeneration (1, 9, 10, 12, 16, 17, 21, 25, 48, 58). Recent studies suggest that these pathological changes in vascular dysfunction during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes are produced, at least in part, by increased contraction of the smooth muscle cells lining the walls of cerebral, mesenteric, retinal, and coronary arteries as well as skeletal arterioles due to elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (4, 5, 7, 25, 35, 48, 49). At present, however, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying this increase in [Ca2+]i are unclear.

Using conventional patch-clamp electrophysiological approaches, several groups have suggested that a cell-wide increase in L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) activity is a likely culprit for elevated [Ca2+]i in arterial smooth muscle during diabetes (5, 35, 48, 52). However, optical recordings of Ca2+ influx events via LTCCs (called “Ca2+ sparklets”) have revealed an unexpected feature of these channels: their activity varies within the surface membrane of multiple cell types (29–32, 43, 47). There are two types of Ca2+ sparklet sites; low and high activity, “persistent” Ca2+ sparklet sites. Activation of protein kinase Cα (PKCα) induces persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. At the physiological membrane potential of −40 mV, and with 2 mM external Ca2+, low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklets contribute to Ca2+ influx and therefore to the regulation of [Ca2+]i in arterial myocytes (2).

Although Ca2+ sparklets have not been examined during acute hyperglycemia and in diabetic smooth muscle, several lines of evidence suggest that an increase in low and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity could contribute to higher Ca2+ influx into cerebral arterial myocytes during the development of diabetes. First, myogenic tone, which requires Ca2+ influx via LTCCs, is increased after acute hyperglycemia and diabetes in cerebral arteries (10, 12, 17, 25, 44, 58). Second, PKC and PKA activity, both of which increase LTCC activity, is increased in smooth muscle during diabetes (13, 26, 48). Third, Ca2+ influx through LTCCs is higher in diabetic than in control smooth muscle (5, 35, 52).

The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that increased low and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity specifically contributes to higher Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells during acute hyperglycemia and in an animal model of non-insulin-dependent, type 2 diabetes, the dB/dB mouse. We focused on cerebral arteries because the mechanisms regulating Ca2+ influx via LTCCs in cerebral arterial myocytes during diabetes have not been investigated. Our results are consistent with a model in which hyperglycemia increases Ca2+ influx into arterial myocytes by increasing low and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial smooth muscle cells. Our data suggest that activation of PKA, not PKCα, contributes to higher persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity during hyperglycemia and diabetes. Furthermore, we found that a scaffolding protein A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) was critical for the local activation of persistent Ca2+ sparklets by PKA during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes. Together, these results support the hypothesis that an increase in low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity may be an early, critical event in the pathway leading to vascular dysfunction during diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of cerebral arterial myocytes.

We used Sprague-Dawley rats as well as wild-type (WT), PKCα-knockout (PKCα−/−) (8), diabetic dB/dB, and control BKS.Cg-m+/+ mice. Animals were euthanized with a lethal intraperitoneal dose of pentobarbital sodium (250 mg/kg for mice and 150 mg/kg for rats), as approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Smooth muscle cells were dissociated from cerebral arteries using standard enzymatic techniques described elsewhere (3). After dissociation, cells were maintained in a nominally Ca2+-free Ringer solution until used. Thapsigargin (1 μM) was included in all solutions used to record Ca2+ sparklets to eliminate Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores during experimentation.

[Ca2+]i and patch-clamp electrophysiology.

Global, cell-wide [Ca2+]i was recorded as described previously (2). Briefly, global [Ca2+]i was imaged in isolated arterial smooth muscle cells loaded with the membrane-permeable acetoxymethyl-ester form of Fluo-4 using a Nikon swept field confocal system coupled to a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope equipped with a Nikon ×60 lens (numerical aperture = 1.4). Background-subtracted images were normalized by dividing the fluorescence intensity of each pixel (F) for the average resting fluorescence intensity (F0) of a confocal image to generate F/F0 images.

Membrane currents were recorded with an Axopatch 200B amplifier using the conventional whole cell patch-clamp configuration. During experiments, cells were continuously superfused with a solution containing (in mM) 120 NMDG, 5 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 20 CaCl2 adjusted to pH 7.4. Pipettes were filled with a solution composed of (in mM) 87 Cs-aspartate, 20 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, and adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. A voltage error of 10 mV attributable to liquid junction potential of these solutions was corrected offline. Whole cell LTCC currents (ICa) were evoked by applying a depolarizing pulse of 200 ms from the holding potential of −70 mV to +30 mV. ICa was measured as the difference between the peak and the sustained current at the end of the 200-ms pulse. Currents were sampled at 20 kHz and low pass-filtered at 2 kHz. Because cerebral arterial myocytes do not express functional voltage-gated T-type Ca2+ channels and ICa in these cells were blocked by dihydropyridine antagonists (41, 57), the voltage-gated, time-dependent currents evoked under these experimental conditions (i.e., Na+- and K+-free external solution) are produced by LTCCs.

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy.

Ca2+ sparklets were recorded in patch-clamped (whole cell configuration) cerebral arterial myocytes as previously described (2). Briefly, we used a through-the-lens total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope built around an inverted Olympus IX-71 microscope equipped with an Olympus PlanApo (×60, numerical aperture = 1.45) oil-immersion lens and an Andor iXON EMCCD camera (South Windsor, CT). To image changes in [Ca2+]i, we added 200 μM of the penta-potassium salt of the Ca2+ indicator fluo-5F to the patch pipette solution. Images were acquired at 100–300 Hz. As before (29, 30), we determined the activity of Ca2+ sparklets by calculating the nPs of each Ca2+ sparklet site, where n is the number of quantal levels and Ps is the probability that a quantal Ca2+ sparklet event is active. All data sets were submitted to a normality test. Because Ca2+ sparklet activity has a bimodal distribution, Ca2+ sparklet sites were grouped into three categories: silent (by default has an nPs of 0), low (nPs between 0 and 0.2), and high (nPs > 0.2). A detailed description of this analysis is given by Navedo et al. (30). Furthermore, readers are referred to a set of step-by-step video tutorials describing our Ca2+ sparklets analysis in our laboratory webpage (http://web.mac.com/fernando_santana/Lab_website/Home.html).

Background fluorescence was subtracted from the total fluorescence signal of fluo-5F-loaded arterial myocytes. Fluo-5F fluorescence values were then converted to Ca2+ concentration units using the “Fmax” equation (24),

as previously described (2). Briefly, F is fluorescence, Fmax is the fluorescence intensity of fluo-5F in the presence of saturating free Ca2+, Kd is the dissociation constant of (fluo-5F = 1,280 nM), and Rf (fluo-5F = 286) is the indicator's Fmax/Fmin ratio. Fmin is the fluorescence intensity of the indicator in a solution where the Ca2+ concentration is 0. Kd and Rf values were determined in vitro using standard methods and are similar to those reported by others (56). Fmax was determined at the end of each experiment by exposing cells to the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (10 μM) and 20 mM external Ca2+.

For these experiments, Ca2+ sparklets were recorded in cells held at the hyperpolarized potential of −70 mV and 20 mM Ca2+ for two reasons. First, we wanted to investigate whether the size of quantal Ca2+ sparklets was altered during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes. Unfortunately, quantal Ca2+ sparklets are very difficult to detect with 2 mM external Ca2+ (29). Second, we wanted to maximize our ability to determine even small changes in Ca2+ sparklet activity during these pathological conditions. This required that we recorded Ca2+ sparklet events with broad range of amplitudes. Note that with 2 mM external Ca2+, most Ca2+ sparklets have amplitudes close to or at our amplitude detection threshold of 18 nM, suggesting the presence of frequent subthreshold Ca2+ sparklets (29). Thus, using 2 mM external Ca2+, although physiologically relevant, may have led to underestimation of Ca2+ sparklet activity because low-amplitude events may fall below our detection threshold.

Plasma glucose.

Plasma glucose levels were measured from tail vein samples using a commercially available kit (One Touch UltraMini, LifeScan, Milpitas, CA) according to manufacturer instructions.

Chemicals and statistical analysis.

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. Normally distributed data are presented as means ± SE. Comparison of the entire nPs data set and nonnormally distributed data was performed using nonparametric data analyses (Mann-Whitney test). Comparison between low and high nPs groups and two-sample comparisons were performed using parametric data analyses (two-tailed, Student's t-test). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Acute hyperglycemia increases L-type Ca2+ currents and global [Ca2+]i in cerebral arterial myocytes.

We measured plasma glucose concentration in control, nondiabetic mice and in an animal model of type 2 diabetes, the dB/dB mouse. Plasma glucose concentration was 9.1 ± 0.3 mM (n = 4) and 22.8 ± 2.0 mM (n = 4) in control and dB/dB mice, respectively. These data are consistent with previous studies suggesting that plasma glucose levels range between 6 and 10 mM in nondiabetic animals and about 20 mM in humans and animal models of type 2 diabetes (21, 27).

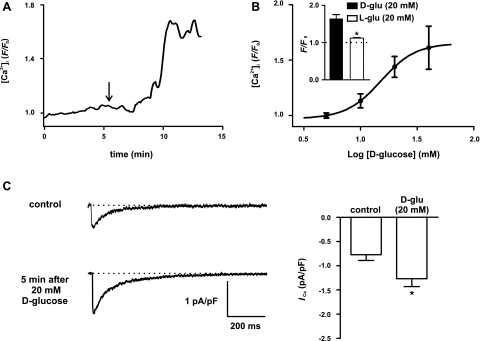

Next, we investigated the effects of acute increases in extracellular d-glucose concentration on global [Ca2+]i in arterial myocytes dissociated from cerebral arteries from nondiabetic, control mice. [Ca2+]i was imaged in cells loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 using a confocal microscope (Fig. 1). Increasing extracellular d-glucose from 10 to 20 mM evoked an increase in global [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1A). We expanded these experiments by examining the effects of a broader range of d-glucose concentrations (5 to 40 mM) on global [Ca2+]i in cerebral arterial myocytes. Note that increasing d-glucose concentration from 5 mM ([Ca2+]i = 1.1 ± 0.02 F/F0) to 10 mM ([Ca2+]i = 1.3 ± 0.07 F/F0) did not increase global [Ca2+]i (n = 6 cells; P > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 1A, an elevation in external d-glucose concentration from 10 mM to 20 mM ([Ca2+]i = 1.6 ± 0.1 F/F0) evoked a significant increase in global [Ca2+]i (P < 0.05). However, we found that increasing external d-glucose from 20 mM to 40 mM ([Ca2+]i = 1.8 ± 0.2 F/F0) did not translate into a further increase in [Ca2+]i (P > 0.05). Indeed, fitting this relationship with a sigmoidal function revealed that the d-glucose concentration that evoked a half-maximal increase (i.e., EC50) in [Ca2+]i was 15 mM.

Fig. 1.

An elevation in extracellular d-glucose increases global intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and L-type calcium channel current (ICa) in rat cerebral arterial myocytes. A: representative trace of global [Ca2+]i in arterial myocyte exposed to 10 mM d-glucose and after application of 20 mM d-glucose (as indicated by the arrow; n = 9 cells). B: concentration-response curve for d-glucose-induced changes in global [Ca2+]i in cerebral arterial myocytes (n = 6 cells). Solid line represents best-fit curve to data determined by a least-squares method using a sigmoidal dose-response equation: y = {A1 + (A2 − A1)/1 + 10[(logEC50 − X) × k]}, where A1 (0.97), A2 (1.65), EC50 (15.16), X (1.20), and k (2.80) are the initial value, final value, the d-glucose concentration at which 50% of the [Ca2+]i response was observed, and the slope factor. Inset: plot of the mean ± SE of global [Ca2+]i in myocytes exposed to 20 mM d-glucose or 20 mM l-glucose. C: representative ICa recordings under control conditions and after acute application of 20 mM d-glucose (n = 7 cells). The graph at right plots the mean ± SE of the amplitude of ICa (at +30 mV) before and after application of 20 mM d-glucose. *P < 0.05.

As a control for these experiments, we examined the effects of the nonmetabolizable levo enantiomer of glucose l-glucose and the nonpermeable sugar mannitol on global [Ca2+]i. Unlike d-glucose, application of 20 mM l-glucose (inset in Fig. 1B) or 20 mM mannitol (not shown) did not increase [Ca2+]i in arterial myocytes (n = 8 cells per experimental group; P < 0.05). Together with the plasma concentration data described above, these findings suggest that changes in external d-glucose between 10 and 20 mM—not changes in the osmolarity of the extracellular solution—are physiologically relevant and translate into sustained elevations in global [Ca2+]i in cerebral arterial smooth muscle.

LTCCs are important regulators of global [Ca2+]i in cerebral arterial myocytes (20, 41). Thus, to investigate the mechanisms by which d-glucose increases [Ca2+]i, we examined the effects of increasing d-glucose from 10 (i.e., control) to 20 mM on ICa in voltage-clamped arterial myocytes (Fig. 1C). In these experiments, ICa was evoked by 200-ms voltage steps from the holding potential of −70 mV to the test potential of +30 mV. Currents were recorded at multiple time points until a steady-state change in whole cell ICa in the presence of 20 mM d-glucose was observed (typically 5 min after exposure to this solution). Consistent with the [Ca2+]i data described above, we found that increasing extracellular d-glucose from 10 to 20 mM increased ICa amplitude by ∼66% (n = 7; P < 0.05). These findings suggest that acute hyperglycemia increases [Ca2+]i, at least in part, by increasing ICa in cerebral arterial myocytes.

Acute elevation of extracellular d-glucose increase Ca2+ sparklets in cerebral arterial myocytes.

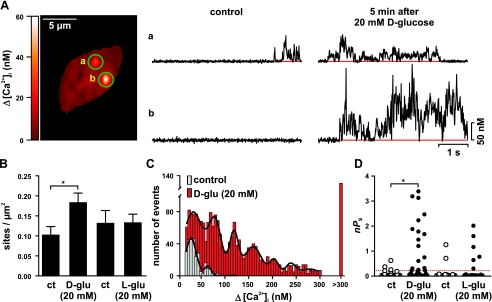

We investigated the mechanisms by which an elevation in d-glucose increases ICa in voltage-clamped cerebral arterial myocytes. To do this, we examined the elementary events of Ca2+ influx via LTCCs in these cells: Ca2+ sparklets (Fig. 2) (29, 50). We determined Ca2+ sparklet density, amplitude, and activity before and after the application of an extracellular solution containing 20 mM d-glucose. As described here in detail in materials and methods and elsewhere (29, 30), Ca2+ sparklet activity was quantified as nPs, where n and Ps are the number of quantal levels and probability of sparklet occurrence, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Consistent with our [Ca2+]i and ICa data above, increasing extracellular d-glucose , but not l-glucose or mannitol, from 10 to 20 mM increased Ca2+ sparklet density nearly 1.8-fold (Fig. 2, A and B; n = 7 cells; P < 0.05). Indeed, analysis of Ca2+ sparklet records indicates that application of 20 mM d-glucose, but not l-glucose or mannitol, augmented total Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes nearly 12-fold by increasing the activity (i.e., nPs) of previously active sparklet sites and by activating new sites (P < 0.05; Fig. 2, A–D).

As part of this analysis, we generated an amplitude histogram of Ca2+ sparklet events under control conditions and after exposure to 20 mM d-glucose (Fig. 2C). As previously reported (29, 30), these Ca2+ sparklet amplitude histograms could be fit with a multi-Gaussian function with a quantal unit of Ca2+ influx of 33 and 34 nM for control and 20 mM d-glucose, respectively. These results indicate that 20 mM d-glucose increases the number of Ca2+ sparklets observed without changing the amplitude of elementary Ca2+ sparklets. Collectively, these findings suggest that elevations in extracellular d-glucose increases ICa and hence global [Ca2+]i by increasing Ca2+ sparklet activity, but not the amplitude of quantal Ca2+ sparklet events in arterial myocytes.

Acute elevation of extracellular d-glucose increases Ca2+ sparklet activity by increasing PKA activity in cerebral arterial myocytes.

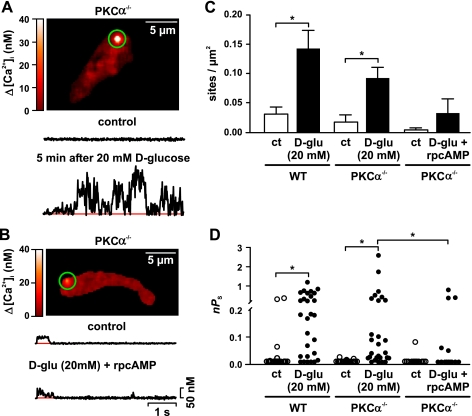

Increased PKC activity has been reported in smooth muscle during diabetes (13, 38, 53, 54). Indeed, recent work from our laboratory (29, 30, 32) suggested that PKCα activity is required for high activity, but not for low activity Ca2+ sparklets. Thus, we investigated whether PKCα was required for the increase in Ca2+ sparklet activity after an elevation in extracellular d-glucose from 10 to 20 mM. In these experiments, the effects of acute hyperglycemia on Ca2+ sparklets were examined in cerebral arterial myocytes from WT and PKCα-null (PKCα−/−) mice.

We found that, like WT (see Fig. 2), increasing d-glucose from 10 to 20 mM increased Ca2+ sparklet site density (from 0.02 ± 0.01 to 0.09 ± 0.05 sparklet sites/μm2) and activity (i.e., nPs; from 0.002 ± 0.001 to 0.29 ± 0.11) in PKCα−/− myocytes (Fig. 3, A, C, and D) (n = 10 cells; P < 0.05). These results suggest that PKCα is not required for increased Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes during acute hyperglycemia. Note, however, that a recent study suggested that high glucose increases Gαs activity, which could increase cAMP production and hence PKA activity (23). Thus, we investigated whether elevations in extracellular glucose increase Ca2+ sparklet activity by activating PKA in arterial myocytes. To do this, we exposed PKCα−/− cerebral arterial myocytes to 20 mM d-glucose in the presence of the PKA inhibitor rpcAMP (100 μM). Consistent with our hypothesis, increasing d-glucose from 10 to 20 mM in the presence of rpcAMP failed to increase Ca2+ sparklet density or activity in PKCα−/− myocytes (Fig. 3, B–D) (n = 10 cells; P > 0.05). This result suggests that hyperglycemia increases Ca2+ sparklet activity through the activation of PKA in cerebral arterial myocytes.

Fig. 3.

PKA, but not PKCα, is required for increased Ca2+ sparklet activity after an elevation in extracellular d-glucose in mouse cerebral arterial myocytes. A and B: TIRF images of representative PKCα−/− arterial myocytes. The traces below the images show the time course of [Ca2+]i in the sites indicated by the green circles before and after exposure to 20 mM d-glucose (n = 10 cells; A) or 20 mM d-glucose + rpcAMP (n = 10 cells; B). C and D: Ca2+ sparklet density (C) and plot of nPs values (D) for individual Ca2+ sparklet sites in wild-type (WT; n = 7 cells) and PKCα−/− arterial myocytes before and after exposure to 20 mM d-glucose or 20 mM d-glucose + rpcAMP. *P < 0.05.

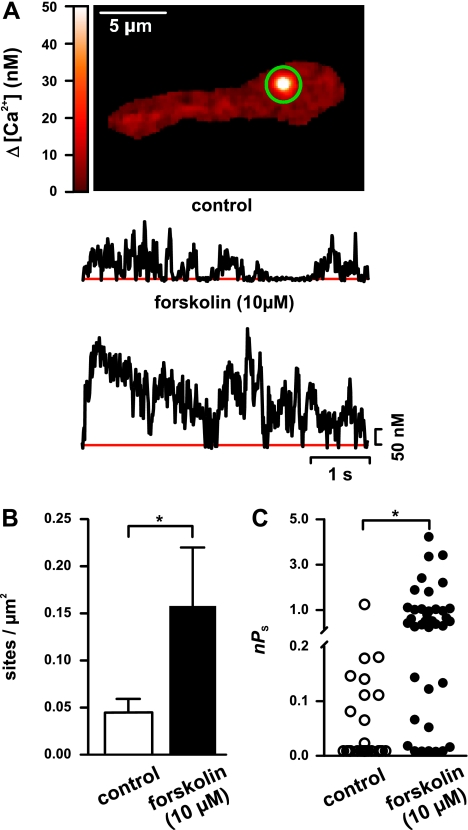

Activation of PKA increases Ca2+ sparklet activity.

A testable prediction of the findings described above is that activation of PKA is sufficient to increase Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes. To test this hypothesis, we examined Ca2+ sparklet activity in WT myocytes before and after the application of the adenyl cyclase activator forskolin (10 μM) in the presence of 10 mM d-glucose (e.g., control solution). Forskolin increases PKA activity by increasing cAMP levels. Consistent with our hypothesis, forskolin increased (P < 0.05, n = 7 cells) Ca2+ sparklet density (from 0.04 ± 0.01 to 0.16 ± 0.06) and activity (from 0.06 ± 0.03 to 0.83 ± 0.17) (Fig. 4), indicating that activation of PKA is sufficient to increase Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes even in the presence of control d-glucose (10 mM) concentration.

Fig. 4.

PKA activation induces persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in rat cerebral arterial myocytes. A: sample TIRF image of a typical WT arterial myocyte. Traces below the image show representative time course of [Ca2+]i in the site indicated by the green circle before and after activation of PKA by forskolin (10 μM). B and C: Ca2+ sparklet density (B) and nPs analysis of Ca2+ sparklet sites (C) before and after application of forskolin. *P < 0.05; n = 7 cells.

Targeting of PKA by AKAP is required for increased Ca2+ sparklet activity during acute hyperglycemia.

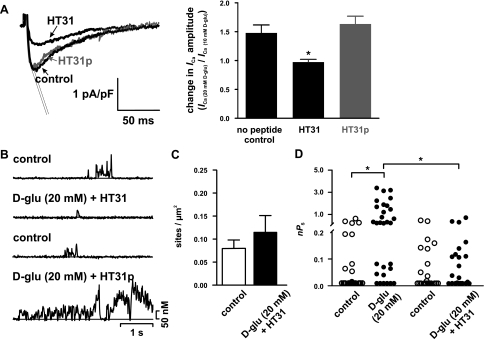

PKA is targeted to specific regions of the surface membrane of mammalian cells by the scaffolding protein AKAP (19, 55). We investigated whether targeting of PKA by AKAP is required for the increase in ICa and Ca2+ sparklet activity during acute hyperglycemia by examining the effects of increasing extracellular glucose in the presence or absence of the specific peptide inhibitor of PKA-AKAP interaction HT31 (10 μM). HT31p (10 μM; a proline-substituted derivative), which does not bind the RII subunit of PKA and hence does not prevent PKA-AKAP interactions, was used as a negative control peptide. In contrast to cerebral arterial myocytes under control conditions [ICa(20 mM d-glucose)/ICa(10 mM d-glucose) = 1.5 ± 0.1; n = 9 cells] or exposed to HT31p [ICa(20 mM d-glucose)/ICa(10 mM d-glucose) = 1.6 ± 0.1; n = 10 cells], application of 20 mM d-glucose did not increase ICa [Fig. 5A; ICa(20 mM d-glucose)/ICa(10 mM d-glucose) = 0.97 ± 0.05; n = 5 cells] and Ca2+ sparklet density or activity (Fig. 5, B–D) in the presence of HT31. These findings suggest that direct targeting of PKA by AKAP is necessary for high glucose-induced increases in Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes.

Fig. 5.

An A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) is required for increased Ca2+ sparklet activity in rat cerebral arterial myocytes after an elevation in extracellular d-glucose. A: representative ICa recordings after acute application of 20 mM d-glucose in cells with no peptide dialyzed (n = 7 cells) and cells dialyzed with HT31 (10 μM) or HT31p (10 μM; n = 6 and 10 cells, respectively). The graph at right plots the mean ± SE of the change in ICa amplitude (at +30 mV) after application of 20 mM d-glucose normalized to the ICa obtained with 10 mM d-glucose. B: representative time courses of [Ca2+]i before and after exposure to 20 mM d-glucose + HT31 (10 μM; n = 9 cells) or 20 mM d-glucose + HT31p (10 μM; n = 6 cells). C and D: Ca2+ sparklet density (C) and scatterplot of nPs values (D) for individual Ca2+ sparklet sites before and after 20 mM d-glucose or 20 mM d-glucose + HT31. *P < 0.05.

Increased Ca2+ sparklet activity in cerebral arterial myocytes from an animal model of type 2 diabetes.

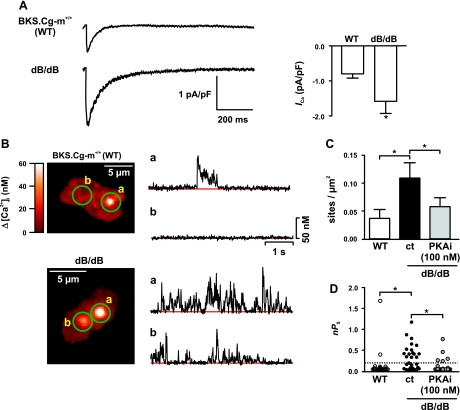

All the experiments described above examined the effects of acute elevations of extracellular d-glucose on ICa and Ca2+ sparklets. Thus, we investigated whether ICa and Ca2+ sparklet activity is increased in cerebral arterial myocytes from 12- to 13-wk-old animal model of type 2 diabetes: the dB/dB mouse (Fig. 6) (21). As a control, we used cerebral smooth muscle cells isolated from aged-match BKS.Cg-m+/+ (WT) mice. Consistent with previous reports (6, 37, 45), we found that body weight (51 ± 0.4 vs. 32 ± 0.5 g; n = 4 mice) and blood glucose (9.1 ± 0.3 and 22.8 ± 2.0 mM; n = 4 mice) were greater in dB/dB than in WT mice (P < 0.05) respectively.

Fig. 6.

ICa and Ca2+ sparklet activity is increased in cerebral arterial myocytes from diabetic mice. A: representative ICa recordings from BKS.Cg-m−/− (WT) and dB/dB arterial myocytes. The graph at right plots the mean ± SE of the amplitude of ICa (at +30 mV) from WT and diabetic arterial myocytes (n = 8 cells per group). B: sample TIRF images from WT (top) and diabetic (bottom) arterial myocytes. Traces at right show time courses of [Ca2+]i in the sites indicated by the green circles from WT and diabetic arterial myocytes. C and D: Ca2+ sparklet density (C) and scatterplot of nPs values (D) from Ca2+ sparklet sites of WT arterial myocytes (n = 13 cells) and diabetic smooth muscle cells (n = 11 cells) before and after PKA inhibition with PKAi (100 nM). *P < 0.05.

ICa was evoked using a voltage protocol similar to one implemented in Fig. 1A. ICa was ∼50% larger in diabetic dB/dB myocytes (1.65 ± 0.15 pA/pF, n = 7 cells) than in WT myocytes (0.75 ± 0.11 pA/pF, n = 7 cells; P < 0.05). In addition, we found that Ca2+ sparklet density and activity were higher (P < 0.05) in dB/dB (0.11 ± 0.03 sites/μm2; nPs = 0.32 ± 0.05; n = 11 cells) than in WT (0.04 ± 0.02 sites/μm2; nPs = 0.13 ± 0.08; n = 13 cells) myocytes (Fig. 6, B–D). Consistent with the hypothesis that PKA is required for increase Ca2+ sparklet activity during hyperglycemia and diabetes, inhibition of this kinase with the specific inhibitor PKAi (100 nM) prevented the increase in Ca2+ sparklet density and activity observed in dB/dB arterial myocytes (P > 0.05; Fig. 6, C–D).

DISCUSSION

The data in this study support a new model for increased Ca2+ influx into arterial myocytes from cerebral arteries during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes. In this model, elevations in extracellular d-glucose from 10 mM to ≥ 20 mM increase the activity of PKA, which translates into an increase in the density and activity of low and persistent Ca2+ sparklet sites in specific regions within the sarcolemma of arterial myocytes. Our data suggest that PKA targeting by an AKAP is essential for increased Ca2+ sparklet activity during hyperglycemia. Thus, an increase in ICa during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes results from an increase in low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklet sites due to activation of AKAP-targeted PKA.

This is the first report suggesting that PKA—via an AKAP—can induce persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial myocytes. At present, the molecular identity of the AKAP isoform(s) responsible for targeting PKA to specific regions of the sarcolemma of arterial myocytes is unclear. One potential candidate is AKAP150, which binds PKA, PKCα, and the Ca2+-sensitive phosphatase calcineurin (also known as protein phosphatase 2B), interacts with LTCCs (14, 19, 36), and is required for PKCα-dependent persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial smooth muscle (30). The functional role of AKAP150 in PKA signaling in arterial myocytes during physiological condition and diabetes is unclear, however. Future studies should address these important issues.

Multiple studies have suggested that PKA activation relaxes arterial smooth muscle by reducing global [Ca2+]i. PKA accomplishes this, at least in part, by increasing the activity of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels, which hyperpolarize and therefore decrease Ca2+ influx through LTCCs (39, 51). Interestingly, PKA also increases LTCC activity (see Fig. 3) (15, 42). These findings raise a difficult question: how can activation of PKA increase LTCC activity and yet decrease global [Ca2+]i in arterial smooth muscle? Although our study does not provide a definitive answer to this question, recent work suggesting compartmentalization of cAMP/PKA signaling in ventricular myocytes may provide insights into this conundrum (11, 18, 28). In these cells, exposing a small fraction of the sarcolemma to the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol caused a local increase in cAMP and PKA activity. This increase in cAMP/PKA signaling was restricted to the site of application of the drug. However, exposing a similar fraction of the sarcolemma of ventricular myocytes to the PKA agonist forskolin resulted in a global, cell-wide increase in cAMP levels (18).

The consensus is that subcellular targeting of adenyl cyclases, PKA, and phosphodiesterases by AKAPs restricts cAMP/PKA signaling to the vicinity of sarcolemmal β-adrenergic receptors that are activated in ventricular myocytes (11, 18, 28). However, by entering the cell and diffusing broadly within it, forskolin causes a global increase in cAMP level that activates PKA in multiple regions within the cell. On the basis of these findings, a model has been proposed in which different PKA targets could be differentially modulated depending on the spatial and temporal characteristics of PKA activation in ventricular myocytes (11, 18, 28).

According to this model, an agonist that primarily activates PKA targeted to the sarcolemma near LTCCs in smooth muscle would increase Ca2+ influx and consequently global [Ca2+]i in these cells. In contrast, an agonist like forskolin, which could induce a cell-wide activation of PKA, would lead to the phosphorylation of multiple proteins including phospholamban, SERCA, ryanodine receptors, BK channels, and LTCCs. In this case, although LTCCs are phosphorylated, [Ca2+]i decreases presumably because the membrane hyperpolarization produced by the activation of BK channels diminishes the activity of LTCCs to a point in which Ca2+ entry is lower than under control conditions. Thus, the functional consequences of a specific PKA agonist would be dependent on the spatiotemporal characteristics of PKA signaling in arterial myocytes. In this model, HG-induced activation of PKA could be restricted to regions of the cell near LTCCs, thus causing increased Ca2+ influx.

Our observation that persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity is increased during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes has important implications. Persistent Ca2+ sparklets activate nearby calcineurin, which dephosphorylates and thereby activates the transcription factor NFATc3 in arterial myocytes during hypertension (33). Elegant work by María Gomez's group suggests that elevations in extracellular glucose activate calcineurin and NFATc3 signaling in cerebral artery smooth muscle (35). Interestingly, activation of NFATc3 can downregulate the expression of the α- and β1-subunits of the large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel and voltage-gated Kv2.1 channels (22, 33, 34). Thus it is intriguing to speculate that an increase in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity contributes, at least in part, to NFATc3 activation and thus decreased K+ channel expression during diabetes. Future studies should examine the relationship between Ca2+ sparklets, NFATc3 activity, and K+ channel expression during diabetes.

Resistance arteries play a crucial role in the regulation of blood pressure and control of tissue perfusion (20). Previous studies have shown enhanced constriction and myogenic tone in cerebral arteries during acute hyperglycemia and in animal models of diabetes (e.g., dB/dB) (10, 12, 17, 25, 44, 58). Several mechanisms may contribute to this change in vascular reactivity. Previous studies have suggested that activation of PKC in cerebral arteries underlies decreased voltage-gated K+ currents in their smooth muscle (40, 44) and impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in these arteries (10, 25, 58) during hyperglycemia and diabetes (e.g., dB/dB mouse). This is important for two reasons. First, together with our findings, it suggests that multiple kinases (i.e., PKA and PKC) are activated during hyperglycemia and diabetes. Second, in vivo, PKC, NFATc3-dependent decreases in K+ currents, and impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation during hyperglycemia and diabetes would depolarize smooth muscle, which would increase low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial myocytes. The data in Fig. 1, A and B, provide examples in which an increase global [Ca2+]i during acute hyperglycemia likely resulted from the combinatorial effects of membrane depolarization and direct LTCC activation by PKA, because the cells examined in these experiments were not voltage clamped.

An interesting observation in our study is that Ca2+ sparklet activity and ICa are higher in dB/dB than in WT arterial myocytes even in the presence of control d-glucose (10 mM) concentration. Note, however, that the differences in Ca2+ sparklet activity are eliminated by PKA inhibition, suggesting that increased Ca2+ sparklet density and activity is the result of higher PKA activity in dB/dB than in WT myocytes under these experimental conditions. Whether higher PKA activity in dB/dB than WT myocytes is the result of differential adenyl cyclase, phosphodiesterase, and/or PKA expression and activity in these cells is presently unclear.

How does an increase in extracellular glucose activate PKA in arterial myocytes? Recent studies suggest an answer to this difficult question. Research from several groups suggested that increased extracellular glucose activates Gαs, which would activate adenyl cyclase and hence the production of cAMP (23, 46). An increase in cAMP would then activate PKA.

To conclude, our data indicate that AKAP-targeted PKA plays a crucial role in the regulation of Ca2+ influx via LTCCs and [Ca2+]i in cerebral vascular smooth muscle during hyperglycemia and diabetes. We demonstrate that increased Ca2+ influx during hyperglycemia and diabetes is not the result of a broad, cell-wide activation of LTCCs. Instead, our data suggest that increased Ca2+ influx in cerebral arterial myocytes during hyperglycemia and diabetes results primarily from increased PKA-dependent low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in specific sarcolemma microdomains. Finally, our data suggest that an increase in number and probability of activation of Ca2+ sparklet sites—not an increase in the quantal unit of Ca2+ influx—underlies increased Ca2+ influx via LTCCs into cerebral arterial myocytes during hyperglycemia and diabetes. These increases in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity could potentially modulate excitability, contraction, and gene expression in smooth muscle during diabetes.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (to M. F. Navedo and L. F. Santana) and National Institutes of Health (to L. F. Santana).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group report on hypertension in diabetes. Hypertension 23: 145–158, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintrón M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Calcium sparklets regulate local and global calcium in murine arterial smooth muscle. J Physiol 579: 187–201, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amberg GC, Santana LF. Downregulation of the BK channel beta1 subunit in genetic hypertension. Circ Res 93: 965–971, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson D. Hyperglycemia and the pathobiology of diabetic complications. Adv Cardiol 45: 1–16, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arun KH, Kaul CL, Ramarao P. AT1 receptors and L-type calcium channels: functional coupling in supersensitivity to angiotensin II in diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res 65: 374–386, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagi Z, Erdei N, Toth A, Li W, Hintze TH, Koller A, Kaley G. Type 2 diabetic mice have increased arteriolar tone and blood pressure: enhanced release of COX-2-derived constrictor prostaglandins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1610–1616, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbagallo M, Shan J, Pang PK, Resnick LM. Glucose-induced alterations of cytosolic free calcium in cultured rat tail artery vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 95: 763–767, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, Kimball TF, Lorenz JN, Nairn AC, Liggett SB, Bodi I, Wang S, Schwartz A, Lakatta EG, DePaoli-Roach AA, Robbins J, Hewett TE, Bibb JA, Westfall MV, Kranias EG, Molkentin JD. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med 10: 248–254, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper ME, Bonnet F, Oldfield M, Jandeleit-Dahm K. Mechanisms of diabetic vasculopathy: an overview. Am J Hypertens 14: 475–486, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Didion SP, Lynch CM, Baumbach GL, Faraci FM. Impaired endothelium-dependent responses and enhanced influence of Rho-kinase in cerebral arterioles in type II diabetes. Stroke 36: 342–347, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink MA, Zakhary DR, Mackey JA, Desnoyer RW, Apperson-Hansen C, Damron DS, Bond M. AKAP-mediated targeting of protein kinase a regulates contractility in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 88: 291–297, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris AK, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Sachidanandam K, Ergul A. Effect of chronic endothelin receptor antagonism on cerebrovascular function in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1213–R1219, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashim S, Li Y, Anand-Srivastava MB. G protein-linked cell signaling and cardiovascular functions in diabetes/hyperglycemia. Cell Biochem Biophys 44: 51–64, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. Distinct enzyme combinations in AKAP signalling complexes permit functional diversity. Nat Cell Biol 7: 1066–1073, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa T, Hume JR, Keef KD. Regulation of Ca2+ channels by cAMP and cGMP in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 73: 1128–1137, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito I, Jarajapu YP, Guberski DL, Grant MB, Knot HJ. Myogenic tone and reactivity of rat ophthalmic artery in acute exposure to high glucose and in a type II diabetic model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 683–692, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarajapu YP, Guberski DL, Grant MB, Knot HJ. Myogenic tone and reactivity of cerebral arteries in type II diabetic BBZDR/Wor rat. Eur J Pharmacol 579: 298–307, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jurevicius J, Fischmeister R. cAMP compartmentation is responsible for a local activation of cardiac Ca2+ channels by beta-adrenergic agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 295–299, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S, Scott JD. Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science 271: 1589–1592, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 508: 199–209, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagaud GJ, Masih-Khan E, Kai S, van Breemen C, Dube GP. Influence of type II diabetes on arterial tone and endothelial function in murine mesenteric resistance arteries. J Vasc Res 38: 578–589, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Layne JJ, Werner ME, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT. NFATc3 regulates BK channel function in murine urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C611–C623, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemaire K, Van de Velde S, Van Dijck P, Thevelein JM. Glucose and sucrose act as agonist and mannose as antagonist ligands of the G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell 16: 293–299, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys J 78: 2655–2667, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayhan WG, Patel Kaushik P. Acute effects of glucose on reactivity of cerebral microcirculation: role of activation of protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1297–H1302, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarty MF. PKC-mediated modulation of L-type calcium channels may contribute to fat-induced insulin resistance. Med Hypotheses 66: 824–831, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moien-Afshari F, Ghosh S, Elmi S, Khazaei M, Rahman MM, Sallam N, Laher I. Exercise restores coronary vascular function independent of myogenic tone or hyperglycemic status in db/db mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1470–H1480, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mongillo M, McSorley T, Evellin S, Sood A, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Huston E, Hannawacker A, Lohse MJ, Pozzan T, Houslay MD, Zaccolo M. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based analysis of cAMP dynamics in live neonatal rat cardiac myocytes reveals distinct functions of compartmentalized phosphodiesterases. Circ Res 95: 67–75, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navedo MF, Amberg G, Votaw SV, Santana LF. Constitutively active L-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11112–11117, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Mechanisms Underlying Heterogeneous Ca2+ Sparklet Activity in Arterial Smooth Muscle. J Gen Physiol 127: 611–622, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Westenbroek RE, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Catterall WA, Striessnig J, Santana LF. Cav1.3 channels produce persistent calcium sparklets, but Cav1.2 channels are responsible for sparklets in mouse arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1359–H1370, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Lederer WJ, McKnight GS, Santana LF. AKAP150 is required for stuttering persistent Ca2+ sparklets and angiotensin II induced hypertension. Circ Res 102: e1–e11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. The control of Ca2+ influx and NFATc3 signaling in arterial smooth muscle during hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15623–15628, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Nichols CB, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Activation of NFATc3 down-regulates the beta1 subunit of large conductance, calcium-activated K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle and contributes to hypertension. J Biol Chem 282: 3231–3240, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson J, Nilsson LM, Chen YW, Molkentin JD, Erlinge D, Gomez MF. High glucose activates nuclear factor of activated T cells in native vascular smooth muscle. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 794–800, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveria SF, Dell'Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron 55: 261–275, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pannirselvam M, Wiehler WB, Anderson T, Triggle CR. Enhanced vascular reactivity of small mesenteric arteries from diabetic mice is associated with enhanced oxidative stress and cyclooxygenase products. Br J Pharmacol 144: 953–960, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel NA, Chalfant CE, Yamamoto M, Watson JE, Eichler DC, Cooper DR. Acute hyperglycemia regulates transcription and posttranscriptional stability of PKCbetaII mRNA in vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J 13: 103–113, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter VA, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Heppner TJ, Stevenson AS, Kleppisch T, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks is involved in regulation of arterial diameter by cyclic nucleotides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1346–C1355, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rainbow RD, Hardy ME, Standen NB, Davies NW. Glucose reduces endothelin inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels in rat arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 575: 833–844, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubart M, Patlak JB, Nelson MT. Ca2+ currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of rat at physiological Ca2+ concentrations. J Gen Physiol 107: 459–472, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruiz-Velasco V, Zhong J, Hume JR, Keef KD. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by cyclic nucleotide cross activation of opposing protein kinases in rabbit portal vein. Circ Res 82: 557–565, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santana LF, Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves-Cintron M, Votaw VS, Ufret-Vincenty CA. Calcium sparklets in arterial smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 1121–1126, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straub SV, Girouard H, Doetsch PE, Hannah RM, Wilkerson MK, Nelson MT. Regulation of intracerebral arteriolar tone by Kv channels: effects of glucose and PKC. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C788–C796, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su J, Lucchesi PA, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Palen DI, Rezk BM, Suzuki Y, Boulares HA, Matrougui K. Role of advanced glycation end products with oxidative stress in resistance artery dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1432–1438, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamaki H. Glucose-stimulated cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biosci Bioeng 104: 245–250, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tour O, Adams SR, Kerr RA, Meijer RM, Sejnowski TJ, Tsien RW, Tsien RY. Calcium green FlAsH as a genetically targeted small-molecule calcium indicator. Nat Chem Biol 3: 423–431, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ungvari Z, Pacher P, Kecskemeti V, Papp G, Szollar L, Koller A. Increased myogenic tone in skeletal muscle arterioles of diabetic rats. Possible role of increased activity of smooth muscle Ca2+ channels and protein kinase C. Cardiovasc Res 43: 1018–1028, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang R, Liu Y, Sauve R, Anand-Srivastava MB. Hyperosmolality-induced abnormal patterns of calcium mobilization in smooth muscle cells from non-diabetic and diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem 183: 79–85, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SQ, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature 410: 592–596, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wellman GC, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Role of phospholamban in the modulation of arterial Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+-activated K+ channels by cAMP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1029–C1037, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White RE, Carrier GO. Vascular contraction induced by activation of membrane calcium ion channels is enhanced in streptozotocin-diabetes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 253: 1057–1062, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams B, Gallacher B, Patel H, Orme C. Glucose-induced protein kinase C activation regulates vascular permeability factor mRNA expression and peptide production by human vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Diabetes 46: 1497–1503, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams B, Schrier RW. Characterization of glucose-induced in situ protein kinase C activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes 41: 1464–1472, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 959–970, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodruff ML, Sampath AP, Matthews HR, Krasnoperova NV, Lem J, Fain GL. Measurement of cytoplasmic calcium concentration in the rods of wild-type and transducin knock-out mice. J Physiol 542: 843–854, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, Berra-Romani R, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J, Blaustein MP, Matteson Role of Cav1 DR.2 L-type Ca2+ channels in vascular tone: effects of nifedipine and Mg2+. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H415–H425, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimmermann PA, Knot HJ, Stevenson AS, Nelson MT. Increased myogenic tone and diminished responsiveness to ATP-sensitive K+ channel openers in cerebral arteries from diabetic rats. Circ Res 81: 996–1004, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]