Abstract

Transient receptor potential channel, vanilloid subfamily member 1 (TRPV1) receptors were identified in human esophageal squamous epithelial cell line HET-1A by RT-PCR and by Western blot. In fura-2 AM-loaded cells, the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin caused a fourfold cytosolic calcium increase, supporting a role of TRPV1 as a capsaicin-activated cation channel. Capsaicin increased production of platelet activating factor (PAF), an important inflammatory mediator that acts as a chemoattractant and activator of immune cells. The increase was reduced by the p38 MAP kinase (p38) inhibitor SB203580, by the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) inhibitor AACOCF3, and by the lyso-PAF acetyltransferase inhibitor sanguinarin, indicating that capsaicin-induced PAF production may be mediated by activation of cPLA2, p38, and lyso-PAF acetyltransferase. To establish a sequential signaling pathway, we examined the phosphorylation of p38 and cPLA2 by Western blot. Capsaicin induced phosphorylation of p38 and cPLA2. Capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation was not affected by AACOCF3. Conversely, capsaicin-induced cPLA2 phosphorylation was blocked by SB203580, indicating that capsaicin-induced PAF production depends on sequential activation of p38 and cPLA2. To investigate how p38 phosphorylation may result from TRPV1-mediated calcium influx, we examined a possible role of calmodulin kinase (CaM-K). p38 phosphorylation was stimulated by the calcium ionophore A23187 and by capsaicin, and the response to both agonists was reduced by a CaM inhibitor and by CaM-KII inhibitors, indicating that calcium induced activation of CaM and CaM-KII results in P38 phosphorylation. Acetyl-CoA transferase activity increased in response to capsaicin and was inhibited by SB203580, indicating that p38 phosphorylation in turn causes activation of acetyl-CoA transferase to produce PAF. Thus epithelial cells produce PAF in response to TRPV1-mediated calcium elevation.

Keywords: capsaicin, esophagus

the transient receptor potential channel, vanilloid subfamily member 1 (TRPV1), originally described in primary sensory neurons as a receptor for capsaicin and related natural irritants (13, 53), is a nonselective cation channel expressed by several cell types including sensory neurons. It is activated by heat, by the pungent ingredient of chili peppers, capsaicin, by endogenous hydrogen ions released in tissues during inflammation (53), or, conceivably, by HCl present in gastric reflux.

TRPV1 activation in primary afferent neurons evokes the sensation of burning pain (including heartburn) and induces neurogenic inflammation by the release of substance P and calcitonin-gene-related peptide. We have recently shown that TRPV1 receptors are present in esophageal epithelial cells and respond to exposure to HCl or capsaicin by producing platelet activating factor (PAF) (17). PAF is an important inflammatory mediator that acts as a chemoattractant and activator of immune cells, with special emphasis on eosinophils (55). PAF induces production of H2O2 in leukocytes (preferentially in eosinophils, Ref. 25) and is among the most important inducers of eosinophil function. It selectively induces the migration of eosinophils over neutrophils (45, 55). It has an important role in eosinophil transmigration through basement membrane components (33); it promotes actin polymerization (51) and eosinophil adherence to vascular endothelial cells (27) and evokes the release of reactive oxygen species by immune cells (44, 60) and by esophageal circular muscle (14, 15). Other than for one experimental study in the opossum (35) and work from our laboratory (14–18), a role of PAF in esophageal inflammation has not been extensively investigated. Because PAF is a potent phospholipid mediator of many leukocyte functions, its activation in esophageal epithelial cells may play an important role in the pathophysiology of inflammatory disorders in the esophagus. This study shows that TRPV1 receptors are present in the esophageal epithelial cells and that their activation leads to production of PAF. Therefore, further study of this signaling pathway is clinically significant.

PAF is synthesized in various cells and tissues via two distinct pathways, the de novo and the remodeling pathways. The de novo pathway involves de novo synthesis of precursor phospholipids, converted to PAF by a unique cholinephosphotransferase (36). This pathway is analogous to phosphatidylcholine synthesis, but the enzymes are specific for the appropriate precursors (36, 41, 46). Several cells that produce PAF (e.g., endothelial cells) do not use the de novo route (36). A function for the de novo pathway has not been clearly established, but it is thought that the de novo pathway may produce a small amount of PAF constitutively where needed to promote appropriate physiological responses (56).

In contrast, the enzymatic synthesis of PAF through the remodeling pathway has been characterized in endothelial cells and other inflammatory and vascular cells (26, 41). This pathway is activated on demand, is highly regulated, and most commonly involves a two-step mechanism. Namely, the precursor of PAF, lyso-PAF, is synthesized by the action of phospholipase A2 (36, 42, 46), removing arachidonic acid (AA) from a membrane phospholipid and resulting in AA and 1-alkyl-phosphatidylcholine (lyso-PAF). Then lyso-PAF is converted to PAF by acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF acetyltransferase (lyso-PAF AT) (58). This pathway may be activated in several cell types by Ca2+ ionophores (43) and by steps involving phosphorylation (36).

To examine how PAF is produced in esophageal epithelial cells in response to TRPV1 receptor activation, we used the human esophageal squamous epithelial cell line HET-1A to elucidate the signal transduction pathway activated by the selective TRPV1 receptor agonist capsaicin. Capsaicin signaling begins with calcium influx through vanilloid receptor channels and ends in production of PAF. Because epithelial cells constitute the first barrier encountered by acid reflux, production of PAF by these cells may be the first step in the inflammatory process. The sequential steps beginning with TRPV1 receptor activation and resulting in PAF production have not been previously described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HET-1A cell culture.

Human esophageal squamous HET-1A cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in the bronchial epithelial cell medium (BEGM BulletKit; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) containing a basal medium (BEBM) plus the additives (BEGM SingleQuots, Lonza) in wells precoated with a mixture of 0.01 mg/ml fibronectin and 0.03 mg/ml vitrogen 100 (Cohesion, Palo Alto, CA). The cell line was cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. The cell line was originally obtained from normal human esophageal autopsy tissue. It has been shown to retain epithelial morphology, and it stains positively for cytokeratins and has remained nontumorigenic (49).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from HET-1A cells. Two micrograms of total RNA were reversely transcribed and then subjected to PCR by using a kit SUPERSCRIPT First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen).

Primers for TRPV1 mRNA were 1) sense: GACTTCAAGGCTGTCTTCATCATCC, 2) antisense: CAGGGAGAAGCTCAGGGTGCGC. The primers were derived from conserved regions of mRNA sequences of humans, rat, dog, mouse, guinea pig, and rabbit. We confirmed, through the BLAST database, that the primers were specific for TRPV1. Reactions were carried out in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) for one cycle at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min.

Ca2± imaging.

Cells were loaded with fura-2 AM 1.25 × 10−6 M for 40 min and placed in a 5-ml chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The cells were allowed to settle onto a coverslip at the bottom of the chamber. The bathing solution was HEPES-buffered solution. After the basal Ca2+ concentration was obtained, capsaicin was added to the bathing solution and the final concentration was 10−5 M. Ca2+ concentrations were measured continuously after adding capsaicin.

Ca2+ measurements were obtained using a modified dual excitation wavelength imaging system (IonOptix, Milton, MA). The Ca2+ concentrations were measured from the ratios of fluorescence elicited by 340-nm excitation to 380-nm excitation using standard techniques (22). Ratiometric images were masked in the region outside the borders of the cell because low photon counts give unreliable ratios near the edges. Peak Ca2+ increase was defined as the difference between the peak value and the basal value.

Western blot analysis.

Cells, incubated in 1.2 mM [Ca2+] BEBM basal medium, were treated with capsaicin (5 × 10−5 M)or with the calcium ionophore A23187 (3 × 10−6 M) alone or after pretreatment with antagonists or inhibitors. The inhibitors included the calmodulin kinase (CaM-K) inhibitors KN93 (5 × 10−6 M) or STO-609 (10−5 M), the CaM inhibitor W-7 (10−5 M), the calcium chelator BAPTA (4 × 10−4 M), the calcium ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (10−7 M), the vanilloid receptor antagonist 5′-iodoresiniferatoxin (5′-IRTX) (10−6 M), the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (10−5 M), or the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) inhibitor AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M). Cells were then lysed in Triton X-100 lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris · HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 40 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 40 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin. The suspension was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 min, and the protein concentration in the supernatant was determined. Western blot was performed as described previously (31). Briefly, after these supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE, the separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a PVDF membrane (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) at 100 V for 60 min. The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk and then incubated with antiphosphorylated p38 MAPK antibody (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or with antiphosphorylated cPLA2 antibody (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling) overnight, followed by 60 min of incubation in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000) (Cell Signaling). Detection was achieved with an enhanced chemiluminescence agent (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

After detecting the phosphorylated p38 MAPK or cPLA2, the membranes were incubated in stripping buffer (100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, and 62.6 mM Tris · HCl, pH 6.7) at 50°C for 30 min, washed three times (10 min each), and then reprobed by using anti-p38 MAPK antibody (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling) or anti-cPLA2 antibody (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling), respectively. Data were normalized to total p38 or total cPLA2 and reported as relative optical density.

Measurement of PAF.

The HET-1A cells were treated for 24 h with 10−7 M capsaicin alone or after 30 min incubation with SB203580 (10−5 M) or with AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M) or with the lyso-PAF AT inhibitor sanguinarin (10−6 M). Culture medium was collected for PAF measurement, and cells were collected for protein measurement.

Measurement of PAF was made using the PAF-[3H] scintillation proximity assay system (TRK 990; Amersham International, Amersham, UK). Scintillation proximity assay is a sensitive assay system that uses microscopic beads containing scintillant that emit light when radiolabeled molecules of interest bind to the surface of the bead.

Lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase activity.

Cells were treated for 45 min with 5 × 10−5 M capsaicin alone or after 30-min incubation with 5′-IRTX (10−6 M) or with SB203580 (10−5 M) or with AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M) or with the MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD98059 (2 × 10−5 M). Cells were scraped from the wells in 200 μl of ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM EDTA, 5 mM mercaptoethanol, 50 mM NaF, 10−5 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 50 mM Tris · HCl (pH 7.4) and homogenized by sonication (4 × 20 s at 1-min intervals). The homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C, 600 g for 10 min. The supernatants were collected for the lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase activity assay, and the protein concentration in the supernatants was measured by the Bradford method (10). The activity of the lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase was measured by a method described by Nomikos et al. (32). Briefly, supernatants containing 10 μg of protein were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 4 nmol of lyso-PAF and 40 nmol of [H3]acetyl-CoA (100 Bq/nmol) in a final volume of 200 μl of 50 mM Tris · HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.25 mg/ml BSA and 1 mM dithiothreitol. After incubation, 4 μl of BSA (100 mg/ml) were added, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 64 μl of 40% cold trichloroacetic acid solution. The reaction mixtures were kept in ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 2 min. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets containing the [H3]PAF bound to the denaturated BSA were dissolved in EcoLume scintillation cocktail (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH); the radioactivity was then determined by liquid scintillation counting. Matching controls were run in the absence of lyso-PAF to subtract the radioactivity of the endogenously produced [H3]PAF.

Drugs and chemicals.

BEBM Basal Medium and BEGM SingleQuots were purchased from Lonza. PD98059, SB203580, and AACOCF3 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); 5′-IRTX was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA); PVDF membrane and [3H]acetyl-CoA was from Perkin Elmer; fura-2 AM and BAPTA were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR); anti-p38 antiphosphorylated p38 antibodies, anti-cPLA2, and antiphosphorylated cPLA2 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology; lyso-PAF was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); STO-609, KN93, W-7, HEPES sodium, capsaicin, and other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical differences between two groups were determined by Student‘s t-test. Differences between multiple groups were tested using ANOVA and checked for significance using Fisher’s protected least significant difference test.

RESULTS

We have previously demonstrated TRPV1-mediated production of PAF in cat esophageal epithelial cells (17). In the present investigation, we examined the signaling pathway responsible for PAF production in the human esophageal epithelial cell line HET-1A, in response to activation of TRPV1 receptors.

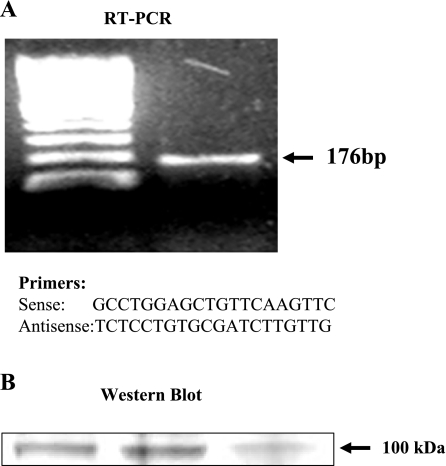

Figure 1 shows RT-PCR and Western blot data for TRPV1 receptors in HET-1A cells. RT-PCR primers were derived from the conserved mRNA sequence of humans and other species (17). A band was recognized as expected (Fig. 1A). The PCR product was sequenced and found to be specific for TRPV1.

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR and Western blot data for transient receptor potential channel, vanilloid subfamily member 1 (TRPV1) receptors, in the cells of a human esophageal squamous epithelial cell line HET-1A. RT-PCR primers were derived from the conserved mRNA sequence of humans and other species. Primers for TRPV1 mRNA are shown. A band was recognized as expected (A). The PCR product was sequenced and found to be specific for TRPV1. To confirm the presence of TRPV1 protein in HET-1A cells, Western Blot analysis was performed. Cells were collected, and a 100-kDa band was immunoblotted with a TRPV1 antibody, confirming the presence of TRPV1 receptors in these esophageal epithelial cells. B: Western blots from 3 separate culture wells containing HET-1A cells.

To confirm the presence of TRPV1 protein in HET-1A cells, Western Blot analysis was performed. Cells were collected, and a 100-kDa band was immunoblotted with a TRPV1 antibody, confirming the presence of TRPV1 receptors in these esophageal epithelial cells (Fig. 1B).

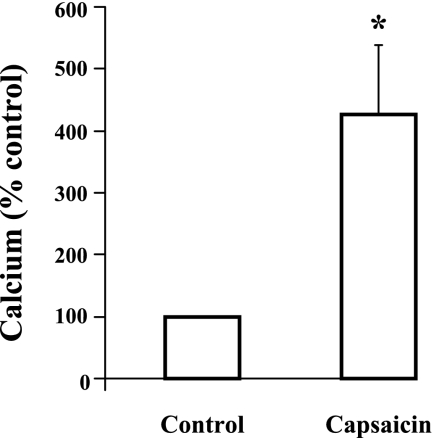

Because TRPV1 is a nonselective cation channel that has been linked to influx of extracellular Ca2+ (13), we examined cytosolic Ca2+ levels in response to the selective TRPV1 receptor agonist capsaicin (Fig. 2). In fura-2 AM-loaded HET-1A cells, capsaicin (10−5 M) caused a gradual increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels that occurred over several minutes, peaking at 4 min, confirming the presence of functional TRPV1 receptors in these epithelial cells.

Fig. 2.

Capsaicin-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase in HET-1A cells. Cells were loaded with fura-2 AM 1.25 × 10−6 M (40 min) and placed in a 5-ml chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The bathing solution was HEPES-buffered solution. After obtaining the basal Ca2+ concentration, capsaicin was added to the bathing solution and the final concentration was 10−5 M. Ca2+ measurements were obtained using a modified dual-excitation wavelength imaging system (IonOptix, Milton, MA). The Ca2+ concentrations were measured from the ratios of fluorescence elicited by 340-nm excitation to 380-nm excitation. In fura-2 AM-loaded HET-1A cells, capsaicin caused an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels that occurred over several minutes, peaking at 4 min (*P < 0.05). Values are means ± SE, N = 8.

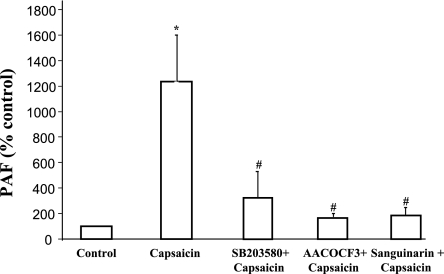

Capsaicin was then used to examine production of PAF in HET-1A cells (Fig. 3). The cells were incubated for 24 h with capsaicin (10−7 M), alone or after 30-min exposure to the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10−5 M) or the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M) or the lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase inhibitor sanguinarin (10−6 M). Because of the prolonged exposure to capsaicin required to measure PAF, a lower concentration was used than the one used in phosphorylation experiments that occur within 30 min. Capsaicin caused a significant increase in PAF levels that was significantly reduced by SB203580, by AACOCF3, and by sanguinarin, indicating that PAF production depends on activation of p38 MAP kinase, cPLA2, and lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase.

Fig. 3.

Capsaicin-induced production of platelet activating factor (PAF) in HET-1A cells. The cells were incubated for 24 h with capsaicin (10−7 M), alone or after 30-min exposure to the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10−5 M), or the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) inhibitor AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M) or the lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase inhibitor sanguinarin (10−6 M). Because of the prolonged exposure to capsaicin required to measure PAF, a lower concentration was used than the one used for phosphorylation experiments that occur within 30 min. Capsaicin caused a significant (*P < 0.001) increase in PAF levels, that was significantly reduced by SB203580 (#P < 0.01), by AACOCF3 (#P < 0.01), and by sanguinarin (#P < 0.01), indicating that PAF production depends on activation of p38 MAP kinase, cPLA2, and lyso-PAF acetyl-CoA transferase. Values are means ± SE for 4 experiments.

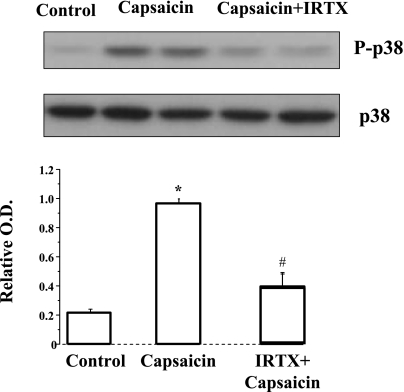

To confirm that capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation is mediated through TRPV1 receptors we examined the effect of the TRPV1 receptor antagonist IRTX. IRTX inhibited capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation, confirming involvement of TRPV1 receptors in this process (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation is mediated through TRPV1 receptors. The cells were incubated for 30 min with capsaicin (5 × 10−5 M), inducing elevated p38 phosphorylation (*P < 0.05). After 30-min pretreatment with the high-affinity TRPV1 antagonist iodoresiniferatoxin (IRTX) (10−6 M), p38 phosphorylation significantly decreased (#P < 0.05), confirming involvement of TRPV1 receptors in capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

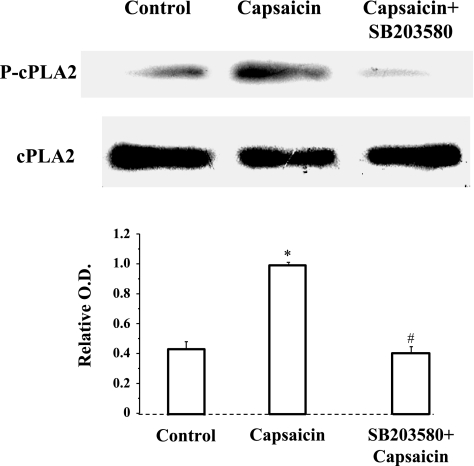

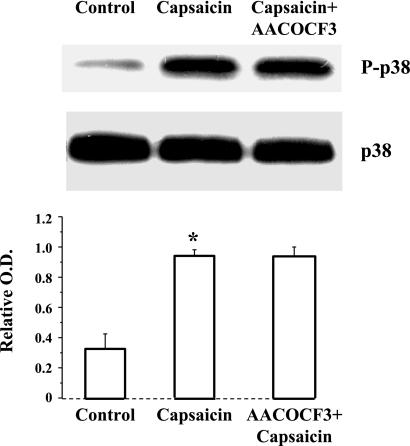

Because p38 phosphorylation and cPLA2 phosphorylation may be involved in TRPV1-induced production of PAF, we examined whether p38 may activate cPLA2 or vice versa. Figure 5 shows that p38 inhibition by SB203580 prevents capsaicin-induced cPLA2 phosphorylation, but the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 has no effect on capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). The data suggest that capsaicin-induced calcium influx results in activation of p38 and p38-induced activation of cPLA2.

Fig. 5.

Capsaicin-induced cPLA2 phosphorylation. 30-min incubation with capsaicin (5 × 10−5 M) caused a significant increase in cPLA2 phosphorylation (*P < 0.01). The increased cPLA2 phosphorylation was significantly reduced (#P < 0.01) by 30-min preincubation with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10−5 M), indicating that cPLA2 phosphorylation depends on activation of p38. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

Fig. 6.

Capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation. 30-min incubation with capsaicin (5 × 10−5 M) caused a significant increase in p38 phosphorylation (*P < 0.01). The increased p38 phosphorylation was not reduced by 30-min preincubation with the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M), indicating that p38 phosphorylation does not depend on activation of cPLA2. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

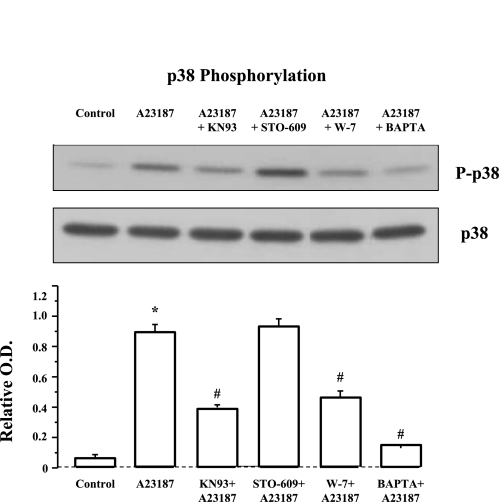

A cytosolic Ca2+ elevation has been shown to activate p38 MAP kinase (28, 57). Figure 7 demonstrates that 30-min incubation with the calcium ionophore A23187 (3 × 10−6 M) induced a significant increase in p38 phosphorylation that was abolished by the extracellular calcium chelator BAPTA (4 × 10−4 M), indicating that a cytosolic calcium elevation induces p38 phosphorylation. To investigate possible mechanisms of calcium-induced p38 phosphorylation, we examined the effect of CaM and of CaM-K inhibitors. The cells were preincubated for 1 h with the CaM-K inhibitors KN93 or STO-609, or the CaM inhibitor W-7. KN93 is a small molecule inhibitor of CaM-KI and CaM-KIV but also inhibits CaM-dependent protein kinase II (30), whereas STO-609 inhibits the two isoforms of CaM-K kinase (CaM-KK) (30), resulting in inhibition of CaM-KI and CaM-KIV, but not CaM-KII. Figure 7 shows that the A23187-induced increase in p38 phosphorylation was inhibited by W-7 and by KN93, suggesting that p38 phosphorylation results from calcium-mediated activation of CaM and CaM-K. Phosphorylation of p38 is most likely mediated by CaM-KII because the calcium-induced phosphorylation was inhibited by KN93 and not by STO-609.

Fig. 7.

A23187-induced p38 phosphorylation. Cells were treated with the calcium ionophore A23187 (3 × 10−6 M, 30 min) alone or after 1-h pretreatment with the calmodulin kinase (CaM-K) inhibitors KN93 (5 × 10−6 M ) or STO-609 (10−5 M), the CaM inhibitor W-7 (10−5 M), or the calcium chelator BAPTA (4 × 10−4 M). The calcium ionophore A23187 induced a significant increase in p38 phosphorylation (*P < 0.001) that was abolished by the extracellular calcium chelator BAPTA (#P < 0.001), indicating that a cytosolic calcium elevation induces p38 phosphorylation. The A23187-induced increase in p38 phosphorylation was inhibited by W-7 (#P < 0.001) and by KN93 (#P < 0.001) but not by STO-609, suggesting that p38 phosphorylation results from calcium-mediated activation of CaM and CaM-K. Inhibition by KN93 but not by STO-609 suggests CaM-KII as the kinase responsible for p38 phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

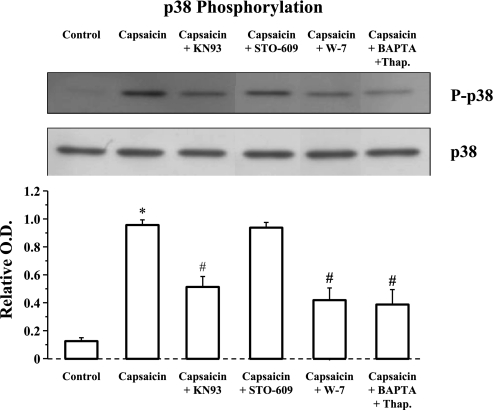

Similarly, capsaicin-induced stimulation of TRPV1 (Fig. 8) resulted in p38 phosphorylation that was inhibited by the extracellular calcium chelator BAPTA (4 × 10−4 M), in combination with the ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin, confirming that a cytosolic calcium elevation mediates capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation. Similarly to A23187, capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation was inhibited by the CaM-K inhibitor KN93 (but not by STO-609) and by the CaM inhibitor W-7.

Fig. 8.

Capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation. Cells were treated with the capsaicin (5 × 10−5 M, 30 min ) alone or after 1-h pretreatment with the CaM-K inhibitors KN93 (5 × 10−6 M) or STO-609 (10−5 M), the CaM inhibitor W-7 (10−5 M), or the calcium chelator BAPTA (4 × 10−4 M) in combination with thapsigargin (10−7 M). Capsaicin induced a significant increase in p38 phosphorylation (*P < 0.001) that was reduced by the combination of BAPTA and thapsigargin (#P < 0.001), indicating that a cytosolic calcium elevation induces p38 phosphorylation. Capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation was inhibited by W-7 (#P < 0.001) and by KN93 (#P < 0.001) but not by STO-609, suggesting that p38 phosphorylation results from calcium-mediated activation of CaM and CaM-K. Inhibition by KN93 but not by STO-609 suggests CaM-KII as the kinase responsible for p38 phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

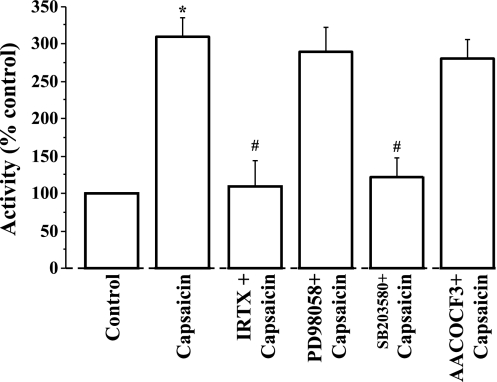

We next examined how these enzymes contribute to activation of lyso-PAF AT. Figure 9 demonstrates that capsaicin-induced activation of lyso-PAF AT is inhibited by the TRPV1 antagonist IRTX, as expected, and by the p38 inhibitor SB203580, indicating that p38 is responsible for activation of the enzyme. In contrast, the MEK inhibitor PD98059 and the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 had no effect on capsaicin-induced lyso-PAF AT activation. The data indicate that p38 (but not ERK1/ERK2) is responsible for lyso-PAF AT activation and that cPLA2, although necessary to remove the AA group from phospholipids, producing lyso-PAF, does not per se contribute to activation of the lyso-PAF AT enzyme.

Fig. 9.

Cells were treated for 45 min with 5 × 10−5 M capsaicin alone or after 30-min incubation with IRTX (10−6 M) or with SB203580 (10−5 M) or with AACOCF3 (2 × 10−5 M) or with the MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD98059 (2 × 10−5 M). Capsaicin caused activation of lyso-PAF acetyltransferase (*P < 0.001) that was inhibited by the TRPV1 antagonist IRTX (#P < 0.001) and by the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (#P < 0.001). In contrast, the MEK inhibitor PD98059 and the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 had no effect on capsaicin-induced lyso-PAF acetyltransferase activation. The data indicate that P38 (but not ERK1/ERK2) is responsible for lyso-PAF acetyltransferase activation and that cPLA2 does not contribute to activation of the lyso-PAF acetyltransferase enzyme. Values are means ± SE for 3 experiments.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that mucosal exposure to acid results in formation of PAF in cat (15, 17) and human (14) esophageal mucosa, and involves HCl-induced activation of TRPV1 receptors (17) in esophageal epithelial cells. TRPV1 receptors are present on esophageal epithelial cells and are directly linked to production of PAF through nonneural mechanisms, causing the initial event responsible for a subsequent cascade of inflammatory mediators in circular muscle (14, 15). PAF is an important inflammatory mediator that acts as a chemoattractant and activator of immune cells, with special emphasis on eosinophils (55). In addition, PAF has been shown to directly contribute to esophageal mucosal damage (35). Because epithelial cells constitute the first barrier encountered by acid reflux, production of PAF by these cells may be the first step in the inflammatory process. Thus PAF may be an important inflammatory mediator contributing to induction of esophagitis.

We therefore investigated the signal transduction pathway mediating TRPV1-induced production of PAF. Individual steps in this pathway have been elucidated in a variety of cell types, but the entire pathway from TRPV1 to PAF has not been previously demonstrated. We used the esophageal epithelial cell line HET-1A that was originally obtained from normal human esophageal autopsy tissue. The HET-1A cell line has been shown to retain epithelial morphology, stains positively for cytokeratins, and has remained nontumorigenic (49). We demonstrate here that HET-1A cells contain vanilloid receptors that are linked to increased cytosolic calcium and produce PAF in response to the selective TRPV1 agonist capsaicin, confirming that TRPV1 receptors are present not only in submucosal neurons, as previously demonstrated (8, 29), but also in the epithelial cells themselves (17), in agreement with recent data by Akiba et al. (1).

PAF is not stored and is produced in response to specific stimuli (36), via a remodeling pathway in which p38 MAPK is required to elicit PAF synthesis (7). PAF is a potent activator of many cell types including platelets, monocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, mast cells, and vascular endothelium. PAF interacts with a single G protein-linked transmembrane receptor that specifically recognizes PAF and related PAF-like lipids and is expressed on the surface of a variety of cell types (37, 59). In the immortalized human keratinocyte-derived cell line HaCaT, acute thermal or oxidative stress induced PAF production (2). In addition, PAF is produced after treatment with the peptide growth factor endothelin-1 or with the calcium ionophore A23187 (2).

PAF biosynthesis involves a two-step enzymatic process yielding the active molecule from the membrane alkyl-ether choline-containing phospholipids. The first step involves a phospholipase A2 that hydrolyzes a long-chain fatty acid (which can be AA) from membrane phospholipids, leaving the intermediate compound lyso-PAF-acether, a PAF-acether precursor that is acetylated by an acetyltransferase in a second step (5). In this pathway, membrane phospholipids are converted by a PLA2 into lyso-PAF, which is then acetylated by the acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT to form PAF (7, 11, 47). In downstream signaling, the ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways can both activate the 85-kDa cPLA2 (27, 31), believed to be essential for PAF synthesis (6, 36), whereas only p38 MAP kinase appears to activate the acetyltransferase (4). Our data are consistent with this pathway, as we show (Fig. 3) that capsaicin-induced production of PAF in HET-1A cells depends on activation of cPLA2 and p38 phosphorylation and activation of acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT. Figure 9 excludes a role of ERK MAP kinase in activation of lyso-PAF AT because the MAP kinase kinase inhibitor PD98059 does not affect lyso-PAF AT activity. Figure 4 demonstrates that capsaicin-induced p38 phosphorylation depends on selective activation of TRPV1, as it is blocked by the selective high-affinity TRPV1 receptor antagonist IRTX (40).

We next examined sequential activation of these enzymes and demonstrated that capsaicin induces phosphorylation/activation of p38 MAP kinase, which is not inhibited by the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (Fig. 6), whereas capsaicin-induced phosphorylation/activation of cPLA2 is blocked by the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 5), indicating that capsaicin-induced phosphorylation/activation of p38 MAP kinase in turn induces phosphorylation/activation of cPLA2 and of the acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT. cPLA2 then converts membrane phospholipids into lyso-PAF, which can then be acetylated by the acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT to form PAF. The activation of cPLA2 is essential for capsaicin-induced production of PAF, as PAF production is blocked by AACOCF3. Once the membrane phospholipids are converted by cPLA2 into lyso-PAF, p38 may directly activate the acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT, and the activation is independent of cPLA2, as shown in Fig. 9.

Several reports have demonstrated, mostly in neurons, that the phosphorylation of p38 is increased by Ca2+ influx (28, 31, 39, 50); for instance, calcium influx into cerebellar granule neurons led to activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (28). Capsaicin injection induced phosphorylated p38 in small-to-medium diameter sensory neurons with a peak at 2 min after injection (31), most likely by increasing calcium influx. It is thought that TRPV1 receptors, initially identified as capsaicin receptors (13), are nonselective cation channels with a preference for Ca2+ that may be activated by heat, low pH, as well as by capsaicin and endogenous proinflammatory substances (13, 20). In HET-1A cells, capsaicin induced a gradual cytosolic calcium increase (Fig. 2) that may initiate the chain of events leading to production of PAF, as it is known that the remodeling pathway utilized in production of PAF may be activated by influx of calcium (2, 4).

This view is consistent with our data (Fig. 7), indicating that Ca2+ influx induced by the calcium ionophore A23187 results in p38 phosphorylation that was abolished by the calcium influx inhibitor BAPTA. Similarly, capsaicin-induced activation of TRPV1 results in p38 phosphorylation that was inhibited by a combination of BAPTA and thapsigargin, supporting the hypothesis that a TRPV1-mediated cytosolic calcium increase contributes to p38 phosphorylation. Thapsigargin was used in conjunction with BAPTA to inhibit possible capsaicin-induced release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum because capsaicin is membrane permeable and TRPV1 receptors have been recently demonstrated in the endoplasmic reticulum (24, 34).

How increased calcium concentration results in phosphorylation and activation of p38 and, eventually, production of PAF (2) has not been clearly demonstrated, but it is known that calcium activates CaM-K, which can phosphorylate p38 (21). Calcium bonds with relatively low affinity with CaM (3, 9, 48, 52), and the Ca2+-CaM complex activates several kinases, including CaM-Ks (30, 52). The finding that the CaM inhibitor W-7 inhibits p38 phosphorylation in response to either A23187 (Fig. 7) or capsaicin (Fig. 8) supports CaM as a participant in this pathway. The CaM-dependent kinases CaM-KI, CaM-KII, and CaM-KIV have broad substrate specificity, whereas CaM-KIII, phosphorylase kinase, has limited substrate specificity (38). The traditional mechanism of activation for the CaM-Ks is through calcium/CaM complex binding, which induces phosphorylation of other CaM-Ks (CaM-KI and CaM-KIV) by CaM-KK (54) or via autophosphorylation (38). CaM-KII is the best characterized of the multifunctional CaM-Ks and is expressed in a variety of tissues (19). Chemical inhibitors, such as KN93, are known to suppress CaM-KII activity but are also effective in inhibiting CaM-KI and CaM-KIV (23, 38). Therefore, inhibition of a cellular process by KN93 implies that the process involves CaM-KI, CaM-KIV, or CaM-KII. Because the two CaM-KKs (α and β) are inhibited by STO-609 and phosphorylate CaM-KI and CaM-KIV but not CaM-KII, inhibition of a cellular process by KN93 but not by STO-609 indicates that it is probably regulated by CaM-KII. The CaM-K cascade, in turn, can activate MAP kinase pathways, particularly JNK and p38 (12, 21). We find that p38 phosphorylation in response to the calcium ionophores A23187 or to the TRPV1 receptor agonist capsaicin is most likely CaM-KII mediated because it is blocked by KN93 but not by STO-609 (Figs. 7 and 8).

P38-induced phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT is thought to be the final step in activation of the enzyme, resulting in production of PAF. Figure 4 confirms that activation of the enzyme by capsaicin is selectively mediated by TRPV1 receptors because it is antagonized by the TRPV1 antagonist IRTX. As expected, acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT activity was reduced by the p38 inhibitor SB203580 but not by the MEK inhibitor PD98058, indicating that p38 (and not ERK1/ERK2) is solely responsible for activation of the enzyme. Activation of acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT was not affected by the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3. This finding indicates that cPLA2 is required only to remove AA from phospholipids, producing the PAF precursor lyso-PAF-acether that may be then acetylated by the acetyltransferase. cPLA2, however, is not required to activate acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT to produce PAF.

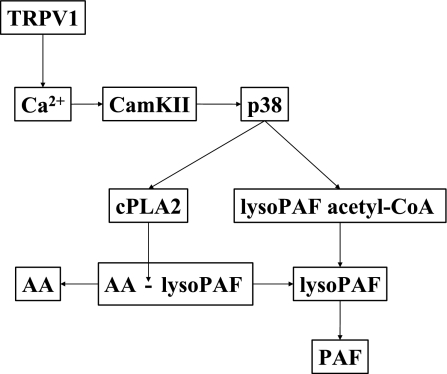

Figure 10 summarizes the findings of this investigation. Activation of TRPV1 causes influx of calcium (and possibly release from intracellular stores) into the cytoplasm, with binding to CaM and activation of CaM-KII. CaM-KII in turn phosphorylates p38, inducing activation of both cPLA2 and acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT. cPLA2 then removes AA from phospholipids, producing the PAF precursor lyso-PAF-acether. Acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF AT then acetylates the lyso-PAF-acether to produce PAF.

Fig. 10.

Summary of the results of this investigation. Activation of TRPV1 causes influx of calcium (and possibly release from intracellular stores) into the cytoplasm, with binding to CaM and activation of CaM-KII. CaM-KII in turn phosphorylates p38, inducing activation of both cPLA2 and acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF acetyltransferase. cPLA2 removes arachidonic acid (AA) from phospholipids, producing the PAF precursor lyso PAF-acether. Acetyl-CoA:lyso-PAF acetyltransferase then acetylates the lyso-PAF-acether to produce PAF.

TRPV1-induced production of PAF by epithelial cells may be a key event contributing to initiation of the inflammatory process.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant RO1-DK-57030 and R01-DK-080703.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiba Y, Mizumori M, Kuo M, Ham M, Guth PH, Engel E, Kaunitz JD. CO2 chemosensing in rat oesophagus. Gut 57: 1654–1664, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alappatt C, Johnson CA, Clay KL, Travers JB. Acute keratinocyte damage stimulates platelet-activating factor production. Arch Dermatol Res 292: 256–259, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen BG, Walsh MP. The biochemical basis of the regulation of smooth muscular contraction. Trends Biochem Sci 19: 362–368, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker PR, Owen JS, Nixon AB, Thomas LN, Wooten R, Daniel LW, O'Flaherty JT, Wykle RL. Regulation of platelet-activating factor synthesis in human neutrophils by MAP kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1592: 175–184, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benveniste J, Chignard M. A role for PAF-acether (platelet-activating factor) in platelet-dependent vascular diseases? Circulation 72: 713–717, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benveniste J, Chignard M, Le Couedic JP, Vargaftig BB. Biosynthesis of platelet-activating factor (PAF-ACETHER). II. Involvement of phospholipase A2 in the formation of PAF-ACETHER and lyso-PAF-ACETHER from rabbit platelets. Thromb Res 25: 375–385, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernatchez PN, Allen BG, Gelinas DS, Guillemette G, Sirois MG. Regulation of VEGF-induced endothelial cell PAF synthesis: role of p42/44 MAPK, p38 MAPK and PI3K pathways. Br J Pharmacol 134: 1253–1262, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat YM, Bielefeldt K. Capsaicin receptor (TRPV1) and non-erosive reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 263–270, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biancani P, Harnett KM, Sohn UD, Rhim BY, Behar J, Hillemeier C, Bitar KN. Differential signal transduction pathways in cat lower esophageal sphincter tone and response to ACh. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 266: G767–G774, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bussolino F, Camussi G. Platelet-activating factor produced by endothelial cells. A molecule with autocrine and paracrine properties. Eur J Biochem 229: 327–337, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai H, Liu D, Garcia JG. CaM Kinase II-dependent pathophysiological signalling in endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 77: 30–34, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389: 816–824, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng L, Cao W, Behar J, Fiocchi C, Biancani P, Harnett KM. Acid-induced release of platelet-activating factor by human esophageal mucosa induces inflammatory mediators in circular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319: 117–126, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng L, Cao W, Fiocchi C, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. HCl-induced inflammatory mediators in cat esophageal mucosa and inflammatory mediators in esophageal circular muscle in an in vitro model of esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G1307–G1317, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng L, Cao W, Fiocchi C, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. Platelet-activating factor and prostaglandin E2 impair esophageal ACh release in experimental esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G418–G428, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng L, de la Monte S, Ma J, Hong J, Tong M, Cao W, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. HCl-activated neural and epithelial vanilloid receptors (TRPV1) in cat esophageal mucosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G135–G143, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Harnett KM, Cao W, Liu F, Behar J, Fiocchi C, Biancani P. Hydrogen peroxide reduces lower esophageal sphincter tone in human esophagitis. Gastroenterology 129: 1675–1685, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colbran RJ. Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J 378: 1–16, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortright DN, Szallasi A. Biochemical pharmacology of the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. An update. Eur J Biochem 271: 1814–1819, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enslen H, Tokumitsu H, Stork PJ, Davis RJ, Soderling TR. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 10803–10808, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hook SS, Means AR. Ca(2+)/CaM-dependent kinases: from activation to function. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 471–505, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karai LJ, Russell JT, Iadarola MJ, Olah Z. Vanilloid receptor 1 regulates multiple calcium compartments and contributes to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem 279: 16377–16387, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato M, Kita H, Tachibana A, Hayashi Y, Tsuchida Y, Kimura H. Dual signaling and effector pathways mediate human eosinophil activation by platelet-activating factor. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 134Suppl1: 37–43, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kihara Y, Ishii S, Kita Y, Toda A, Shimada A, Shimizu T. Dual phase regulation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by platelet-activating factor. J Exp Med 202: 853–863, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimani G, Tonnesen MG, Henson PM. Stimulation of eosinophil adherence to human vascular endothelial cells in vitro by platelet-activating factor. J Immunol 140: 3161–3166, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao Z, Bonni A, Xia F, Nadal-Vicens M, Greenberg ME. Neuronal activity-dependent cell survival mediated by transcription factor MEF2. Science 286: 785–790, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews PJ, Aziz Q, Facer P, Davis JB, Thompson DG, Anand P. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1 nerve fibres in the inflamed human oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 16: 897–902, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Means AR. The year in basic science: calmodulin kinase cascades. Mol Endocrinol 22: 2759–2765, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizushima T, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Fukuoka T, Tokunaga A, Mashimo T, Noguchi K. Activation of p38 MAPK in primary afferent neurons by noxious stimulation and its involvement in the development of thermal hyperalgesia. Pain 113: 51–60, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomikos TN, Iatrou C, Demopoulos CA. Acetyl-CoA:1-O-alkyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine acetyltransferase (lyso-PAF AT) activity in cortical and medullary human renal tissue. Eur J Biochem 270: 2992–3000, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. Transmigration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: synergistic effects of platelet-activating factor and eosinophil-active cytokines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 16: 455–463, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olah Z, Szabo T, Karai L, Hough C, Fields RD, Caudle RM, Blumberg PM, Iadarola MJ. Ligand-induced dynamic membrane changes and cell deletion conferred by vanilloid receptor 1. J Biol Chem 276: 11021–11030, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson WG, Kieffer CA, Feldman MJ, Miller DV, Morris GP. Role of platelet-activating factor in acid-induced esophageal mucosal injury. Dig Dis Sci 52: 1861–1866, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem 265: 17381–17384, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 419–445, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Mora OG, LaHair MM, McCubrey JA, Franklin RA. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase I and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase participate in the control of cell cycle progression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 65: 5408–5416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitoh T, Tanaka S, Koike T. Rapid induction and Ca(2+) influx-mediated suppression of vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 (VDUP1) mRNA in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis. J Neurochem 78: 1267–1276, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seabrook GR, Sutton KG, Jarolimek W, Hollingworth GJ, Teague S, Webb J, Clark N, Boyce S, Kerby J, Ali Z, Chou M, Middleton R, Kaczorowski G, Jones AB. Functional properties of the high-affinity TRPV1 (VR1) vanilloid receptor antagonist (4-hydroxy-5-iodo-3-methoxyphenylacetate ester) iodo-resiniferatoxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 1052–1060, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serhan CN, Haeggstrom JZ, Leslie CC. Lipid mediator networks in cell signaling: update and impact of cytokines. FASEB J 10: 1147–1158, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu T, Ohto T, Kita Y. Cytosolic phospholipase A2: biochemical properties and physiological roles. IUBMB Life 58: 328–333, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shindou H, Ishii S, Uozumi N, Shimizu T. Roles of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) and platelet-activating factor receptor in the Ca-induced biosynthesis of PAF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 271: 812–817, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shute JK, Rimmer SJ, Akerman CL, Church MK, Holgate ST. Studies of cellular mechanisms for the generation of superoxide by guinea-pig eosinophils and its dissociation from granule peroxidase release. Biochem Pharmacol 40: 2013–2021, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sigal CE, Valone FH, Holtzman MJ, Goetzl EJ. Preferential human eosinophil chemotactic activity of the platelet-activating factor (PAF) 1–0-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphocholine (AGEPC). J Clin Immunol 7: 179–184, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snyder F. Platelet-activating factor and its analogs: metabolic pathways and related intracellular processes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1254: 231–249, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snyder F, Fitzgerald V, Blank ML. Biosynthesis of platelet-activating factor and enzyme inhibitors. Adv Exp Med Biol 416: 5–10, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stoclet JC, Gerard C, Killhoffer MC, Lucnier C, Miller R, Schaeffer P. Calmodulin and its role in intracellular calcium regulation. Prog Neurobiol 29: 321–364, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoner GD, Kaighn ME, Reddel RR, Resau JH, Bowman D, Naito Z, Matsukura N, You M, Galati AJ, Harris CC. Establishment and characterization of SV-40 T-antigen immortalized human esophageal epithelial cells. Cancer Res 51: 365–371, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stringaris AK, Geisenhainer J, Bergmann F, Balshusemann C, Lee U, Zysk G, Mitchell TJ, Keller BU, Kuhnt U, Gerber J, Spreer A, Bahr M, Michel U, Nau R. Neurotoxicity of pneumolysin, a major pneumococcal virulence factor, involves calcium influx and depends on activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Neurobiol Dis 11: 355–368, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki M, Kato M, Hanaka H, Izumi T, Morikawa A. Actin assembly is a crucial factor for superoxide anion generation from adherent human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 112: 126–133, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swulius MT, Waxham MN. Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2637–2657, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev 51: 159–212, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tokumitsu H, Enslen H, Soderling TR. Characterization of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Molecular cloning and expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem 270: 19320–19324, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wardlaw AJ, Moqbel R, Cromwell O, Kay AB. Platelet-activating factor. A potent chemotactic and chemokinetic factor for human eosinophils. J Clin Invest 78: 1701–1706, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodard DS, Lee TC, Snyder F. The final step in the de novo biosynthesis of platelet-activating factor. Properties of a unique CDP-choline:1-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol choline-phosphotransferase in microsomes from the renal inner medulla of rats. J Biol Chem 262: 2520–2527, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright DC, Geiger PC, Han DH, Jones TE, Holloszy JO. Calcium induces increases in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha and mitochondrial biogenesis by a pathway leading to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem 282: 18793–18799, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wykle RL, Malone B, Snyder F. Enzymatic synthesis of 1-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, a hypotensive and platelet-aggregating lipid. J Biol Chem 255: 10256–10260, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM. The platelet-activating factor signaling system and its regulators in syndromes of inflammation and thrombosis. Crit Care Med 30: S294–S301, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zoratti EM, Sedgwick JB, Vrtis RR, Busse WW. The effect of platelet-activating factor on the generation of superoxide anion in human eosinophils and neutrophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 88: 749–758, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]