Abstract

We have used the two-electrode voltage clamp technique and the patch clamp technique to investigate the regulation of ROMK1 channels by protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) and protein-tyrosine kinase (PTK) in oocytes coexpressing ROMK1 and cSrc. Western blot analysis detected the presence of the endogenous PTP-1D isoform in the oocytes. Addition of phenylarsine oxide (PAO), an inhibitor of PTP, reversibly reduced K+ current by 55% in oocytes coinjected with ROMK1 and cSrc. In contrast, PAO had no significant effect on K+ current in oocytes injected with ROMK1 alone. Moreover, application of herbimycin A, an inhibitor of PTK, increased K+ current by 120% and completely abolished the effect of PAO in oocytes coexpressing ROMK1 and cSrc. The effects of herbimycin A and PAO were absent in oocytes expressing the ROMK1 mutant R1Y337A in which the tyrosine residue at position 337 was mutated to alanine. However, addition of exogenous cSrc had no significant effect on the activity of ROMK1 channels in inside-out patches. Moreover, the effect of PAO was completely abolished by treatment of oocytes with 20% sucrose and 250 μg/ml concanavalin A, agents that inhibit the endocytosis of ROMK1 channels. Furthermore, the effect of herbimycin A is absent in the oocytes pre-treated with either colchicine, an inhibitor of microtubules, or taxol, an agent that freezes microtubules. We conclude that PTP and PTK play an important role in regulating ROMK1 channels. Inhibiting PTP increases the internalization of ROMK1 channels, whereas blocking PTK stimulates the insertion of ROMK1 channels.

ROMK, a cloned inward rectifying K+ channel from the renal outer medulla, is a key component of the small conductance K+ channel identified in the thick ascending limb and cortical collecting duct (CCD)1 (1-3). This conclusion is based on observations that the conductance, open probability, opening and closing kinetics, and pH sensitivity of ROMK are similar to that of the native small conductance K+ channel (1, 3, 4). Moreover, both K+ channels are regulated by protein kinase A and protein kinase C (5-10). A difference between the native small conductance K+ channel and ROMK is that ROMK is insensitive to sulfonylurea agents, whereas the native small conductance K+ channel is inhibited by sulfonylurea agents (11-13). Three isoforms of ROMK, ROMK1, -2, and -3, have been found in the rat kidney (14). Based on in situ hybridization, ROMK1 is located in the apical membrane of principal cells in the CCD, whereas ROMK2 and -3 are expressed at the thick ascending limb (14). The principal cell in the CCD is responsible for Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion, which takes place by K+ entering the cell across the basolateral membrane via Na,K-ATPase followed by diffusion into the lumen across the apical membrane through ROMK1-like channels (15).

We have previously demonstrated that inhibition of PTP reduced the activity of the small conductance K+ channel in the apical membrane of the CCD of rat kidney (16). Moreover, we have reported that blocking PTK increased the number of the small conductance K+ channels in the CCD obtained from rats on a K+-deficient diet (17). Therefore, we have suggested that PTK and PTP play a key role in the regulation of the small conductance K+ channel in the rat CCD.

In the present study, we have extended the investigation to explore the mechanism by which PTK and PTP regulate ROMK1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The reasoning for studying ROMK1 is that it is exclusively expressed in the CCD. We have observed that tyrosine residue 337 in the C terminus of ROMK1 is essential for mediating the effects of PTK and PTP on the channel activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Xenopus Oocytes

Xenopus laevis females were obtained from Nasco (Fort Atkinson, WI). The method for obtaining oocytes has been described previously (18). We removed the follicular layer of oocytes under a dissecting microscope with two watchmaker forceps. After dissection, the oocytes were incubated over night at 19 °C in a solution containing 66% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 medium with freshly added 2.5 mM sodium pyruvate and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. Viable oocytes were selected and micro-injected with ROMK1 cRNA alone (10 ng) or with a mixture of ROMK1 and cSrc(15 ng). The oocytes were incubated at 19 °C in a 66% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 medium, and experiments were performed on days 2–3 after injection. To remove the vitellin membrane, oocytes were treated with hypertonic solution containing 220 mM methylglucamine, 220 mM aspartic acid, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2).

Patch Clamp Technique

Patch clamp electrodes were pulled from glass capillary tubes (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN), with resistance of 4–6 megohms when filled with a solution containing 150 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. An Axonpatch200B patch clamp amplifier (Axon, Foster city, CA) was used to record channel current. Channel currents were low pass-filtered at 1 kHz by an eight-pole Bessel filter (902LPF, Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA) and were digitized by a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Burlington, CA). Data were acquired to a Pentium PC (Gateway) at a sampling rate of 5 kHz and analyzed with pClamp software system (6.04, Axon Instruments, Burlington, CA). Channel activity was defined as NPo, which was calculated from data samples of 30–60 s duration. We use the following equation to obtain NPo,

| (Eq. 1) |

where ti is the fractional open time spent at each of the observed current levels.

Two-electrode Whole Cell Voltage Clamp

A Warner oocyte clamp OC-725C was used to measure the whole cell K+ current. Voltage and current microelectrodes were filled with 1 M KCl and had resistance of less than 2 megohms. Series resistance of the pipette was compensated. The current was recorded on a chart recorder (Gould TA240). To exclude the leaky current, 2 mM Ba2+ was used before and after each maneuver to determine the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current.

Western Blot

Approximately 40 oocytes were transferred to a polypropylene test tube containing 2 ml of buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 25 μg/ml leupeptin, 25 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 300 mM sucrose). Oocytes were homogenized on ice in the following way. They were exposed to a Polytron mechanical homogenizer for 5 s and then left unstirred for an additional 5 s. This procedure was repeated three times. Protein concentration was assayed using the Bradford standard assay, with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Antibodies to cSrc and PTP1D were obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY).

Fluorescence Localization of ROMK1

Oocytes were injected with cRNA encoding cSrc (15 ng) and GFP-ROMK1 (10 ng) or with GFPROMK1 alone. Three groups of oocytes (five oocytes/group) were studied: 1) GFP-ROMK1; 2) cSrc and GFP-ROMK1; and 3) water. We examined the effects of PAO and herbimycin A on the membrane expression of ROMK1 48 h after injection with laser scanning confocal microscopy. Five sections of each oocyte membrane were recorded, and the signal was averaged for each egg. Oocytes were imaged using a Bio-Rad MRC1000 confocal microscope. GFP fluorescence was excited at 488 nM with an argon laser beam and viewed with an inverted Olympus microscope equipped with a × 20 dry lens. XY scans were obtained at approximately the midsection of each egg. All images were acquired, processed, and printed with identical parameters. We used Scion Image software (Scion Co., Frederick, MD) to determine the GFP fluorescence intensity before (control) and after adding either PAO or herbimycin A. The background fluorescence taken from water-injected oocytes was subtracted from the mean value of each measurement.

Preparation of cRNA for Oocyte Injection

The preparation of cRNA encoding the ROMK1 channel has been previously described (7). The GFP-ROMK1 cDNA construct was prepared as follows. Full-length ROMK1 cDNA was made from PCDNA3.1/ROMK1 using the polymer-ase chain reaction technique. The forward primer was TTGTAGGTGGAAGGATCCTGCTACATCTGGGTGTCG, and the reverse primer was TGGGCCTAAAAGAATTCAGCTGCTGTGCACGACAAC. The 1.2-kilo-base cDNA digested with EcoRI and BamHI was cloned into PEGFPC vector (CLONTECH) cut with the same restriction enzymes. The sequence of the GFP-ROMK1 construct was confirmed by sequencing (W. M. Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University, New Haven, CT). To make cRNA coding GFP-ROMK1, cDNA of the fusion protein was subcloned into pSport vector and transcribed in vitro from the T7 promotor. For preparation of cRNA of cSrc that was subcloned into the ACC1/EcoRI site of the pGEm3Z vector, the DNA of cSrc was linearized with EcoRI and transcribed in vitro by using the Sp6 transcription kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Experimental Solution and Statistics

The bath solution for the patch clamp study and two-electrode voltage clamp was composed of the following (in mM): 150 KCl, 2.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 EGTA, 5 HEPES (pH 7.4). Herbimycin A and phenylarsine oxide were purchased from Sigma and added directly to the bath to reach the final concentration. We present data as means ± S.E. The Student's t test was used to determine the significance.

RESULTS

To study the role of PTK in regulating ROMK1 channels, we coinjected oocytes with cRNA encoding cSrc and ROMK1, respectively. Fig. 1 is a representative Western blot showing that cSrc is highly expressed in the oocytes injected with cRNA of cSrc, whereas the cSrc is present only at negligible levels in oocytes without injection with cSrc cRNA. We also carried out Western blot analysis to identify the expression of PTP iso-forms. We observed that PTP1D, a membrane associate PTP isoform, is expressed in Xenopus oocytes; its expression is not affected by injecting cSrc RNA. In contrast, expression of PTP-1B and PTP-1C in oocytes was not detected with the current method (data not shown).

FIG. 1. A Western blot shows the expression of cSrc and PTP-1D in oocytes injected with cSrc + ROMK1 (lanes 1 and 3) and in oocytes injected with ROMK1 alone (lanes 2 and 4).

The protein concentration in lanes 1 and 2 was 5 μg, whereas in lanes 3 and 4 it was 10 μg. PC, positive control.

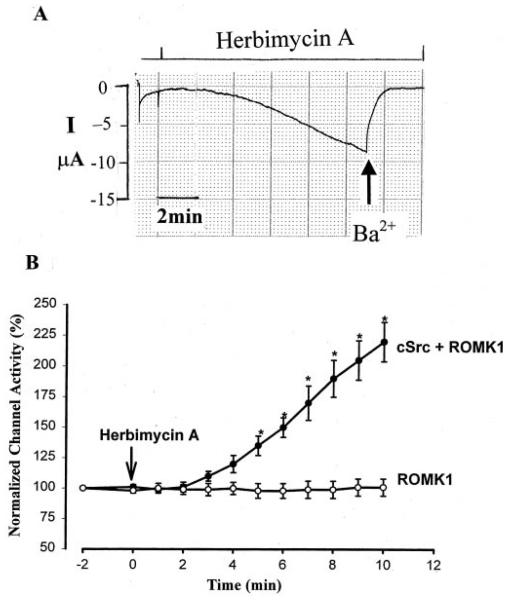

After confirming that cSrc is expressed in oocytes injected with cSrc cRNA, we used the two-electrode voltage clamp technique to study the role of cSrc in regulating the activity of ROMK1 channels. Fig. 2A is a recording showing the effect of herbimycin A, an inhibitor of cSrc, on the K+ current in oocytes coexpressing ROMK1 and cSrc. It is apparent that inhibition of PTK with 1 μM herbimycin A significantly increases the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current within 10 min. Fig. 2B summarizes results from 38 experiments in oocytes coexpressing ROMK1 and cSrc. It illustrates that inhibition of PTK augments the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current by 120 ± 16%, from 6.4 ± 0.9 to 14.1 ± 1.6 μA within 10 min. The effect of herbimycin A was specifically related to the inhibition of PTK, because the agent had no significant effect on the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current in the oocytes expressing ROMK1 alone.

FIG. 2.

A, a recording showing the effect of 1 μM herbimycin A on the K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 and cSrc. The current was measured with a two-electrode voltage clamp. At the end of the experiment, Ba2+ (arrow) was added to determine the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current. I, current. B, a summary showing the time course of the effect of herbimycin A on the normalized channel activity in oocytes expressing ROMK1 alone or ROMK1 + cSrc. The asterisks indicate that the differences are significant in comparison with the corresponding values obtained in oocytes injected with ROMK1 alone.

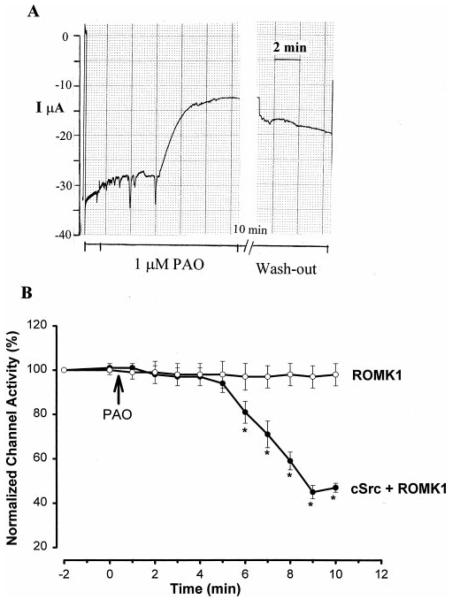

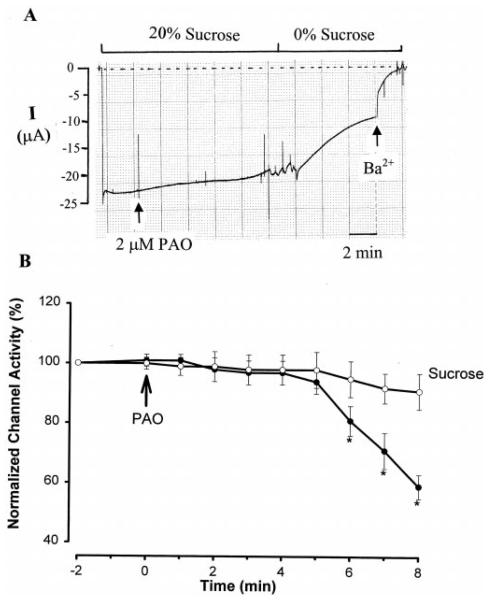

After establishing the role of cSrc in suppressing the activity of ROMK1 channels, we investigated the effect of PAO, an inhibitor of PTPs including PTP1D, on ROMK1 channels (19). Fig. 3A is a recording demonstrating the effect of 1 μM PAO on the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 and cSrc. Inhibiting PTP significantly decreased K+ current, and the effect of PAO was reversible, because it was observed in separate experiments that the K+ current returned to the control value 60 min after removal of PAO (data not shown). Fig. 3B summarizes the results of 22 experiments in which the effect of PAO was examined. Blocking PTP with 1 μM PAO reduced the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current by 53 ± 2%, from 21 ± 2 to 10 ± 1 μA. The effect of PAO was the result of inhibiting PTP, because PAO had no significant effect on channel activity in the oocytes expressing ROMK1 alone.

FIG. 3.

A, a recording showing the effect of 1 μM PAO on the K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 and cSrc. After washout of PAO, the pen speed of the paper recorder was set to zero and resumed to 1 cm/2 mm 10 min later. This stop-go causes a jump of the trace shown in the figure because of an increase in K+ current. I, current. B, a summary showing the time course of the effect of PAO on the normalized channel activity in oocytes expressing ROMK1 alone or ROMK1 + cSrc. The asterisks indicate that the differences are significant in comparison with the corresponding values obtained in oocytes injected with ROMK1 alone.

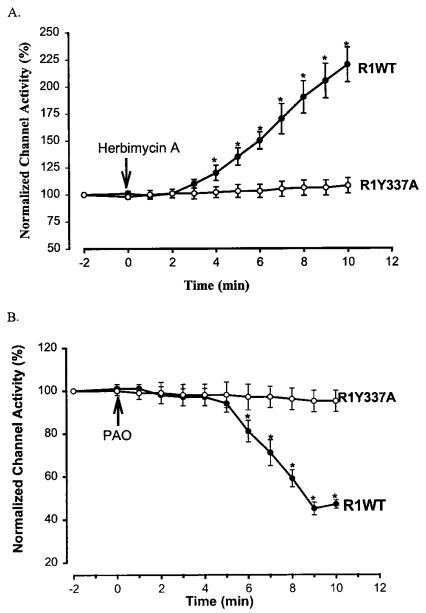

The amino acid sequence of ROMK1 contains the tyrosine residue 337 at the C terminus, which is within a consensus PTK phosphorylation site. To test whether tyrosine residue 337 of the C terminus was involved in mediating the effect of PTK or PTP, we investigated the effect of herbimycin A or PAO on the ROMK1 mutant R1Y337A in which the tyrosine residue was mutated to alanine. Fig. 4A summarizes the results of 15 experiments in which the effect of 1 μM herbimycin A on channel activity in oocytes expressing cSrc and R1Y337A was studied. Clearly, the effect of herbimycin A was absent in oocytes expressing the ROMK1 mutant (108 ± 7% of the control K+ current). Furthermore, Fig. 4B demonstrates that PAO had no significant effect on channel activity (95 ± 5% of the control value) in oocytes expressing R1Y337A (n = 9). This strongly suggests that tyrosine residue 337 at the C terminus is essential for the effects of PTK and PTP on channel activity.

FIG. 4.

A, the effect of 1 μM herbimycin A on K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 (R1WT) + cSrc (filled circles) and the ROMK1 mutant (R1Y337A) + cSrc (open circles), respectively. Asterisks indicate that the difference between two groups is significant. B, the effect of 1 μM PAO on K+ current in oocytes expressing R1WT + cSrc (filled circles) and R1Y337A + cSrc (open circles), respectively.

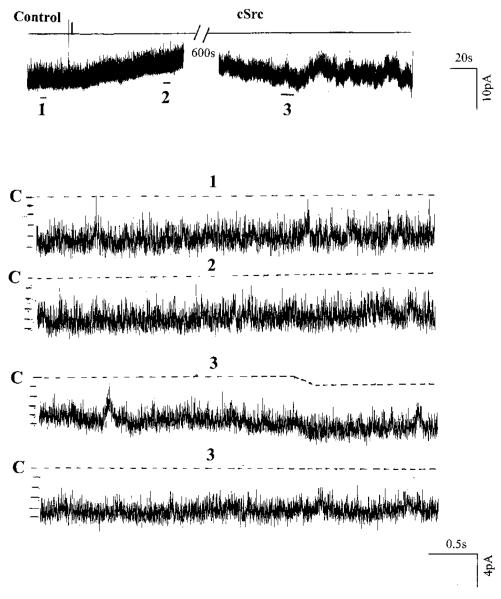

To explore the possibility that PTK-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of ROMK1 or its closely associated proteins directly inhibits channel activity, we examined the effect of exogenous cSrc on the activity of the ROMK1 channel in inside-out patches. Fig. 5 is a representative recording from four such experiments showing the effect of exogenous cSrc on ROMK1 channels in an inside-out patch. The activity of cSrc was independently confirmed by assessing the phosphorylation rate of a specific peptide (data not shown). We observed that adding 1 nM cSrc had no effect on channel activity within 10–15 min (99 ± 4% of the control value). This does not support the possibility that PTK-mediated phosphorylation of ROMK1 directly inhibits the channel. The finding that cSrc did not inhibit the ROMK1 channel in excised patches is, however, consistent with the previous observation that addition of exogenous cSrc had no significant effect on the activity of the small conductance K+ channel in the rat CCD (17).

FIG. 5. A channel recording demonstrating the effect of exogenous cSrc (1 nM) on the activity of ROMK1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

The experiment was performed in an inside-out patch, and the holding potential was 0 mV. The channel closed state is indicated by C and a dotted line. Three parts of the trace indicated by numbers are extended to show the fast time resolution.

Because PTK is involved in the regulation of membrane protein trafficking (20), it is possible that tyrosine phosphorylation of ROMK1 channels stimulates endocytosis of ROMK1 channels from the cell membrane. This possibility was tested by experiments in which the effect of PAO was examined in the presence of 20% sucrose, which blocks endocytosis. Fig. 6A is a representative recording showing the effect of 2 μM PAO on the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current in oocytes coexpressing ROMK1 and cSrc in the presence or absence of 20% sucrose. In the presence of 20% sucrose, addition of PAO decreased K+ current only by a modest 9 ± 1% (n = 15; Fig. 6B). Fig. 6A also shows that removal of sucrose restored the inhibitory effect of PAO, which reduced the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current by 50 ± 4%. The decrease in K+ current after the removal of sucrose was the result of inhibiting PTP, because removal of sucrose per se had no significant effect on channel activity in the absence of PAO (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

A, a recording illustrating the effect of 2 μM PAO on the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 + cSrc in the presence or absence of 20% sucrose. The zero current is indicated by a dotted line. I, current. B, the time course of the effect of PAO on K+ current in the presence of 20% sucrose (open circles) and in the absence of sucrose (filled circles). Asterisks indicate that the difference between two groups is significant.

Moreover, we studied the effect of PAO on channel activity in the presence of concanavalin A, an agent that blocks endocytosis (21). Treatment of the oocytes with 250 μg/ml concanavalin A completely abolished the inhibitory effect of PAO (control, 15 ± 0.8 μA; PAO + concanavalin A, 15.9 ± 1.2 μA; n = 5; data not shown). This suggested that inhibition of PTP stimulates the endocytosis of ROMK1 channels.

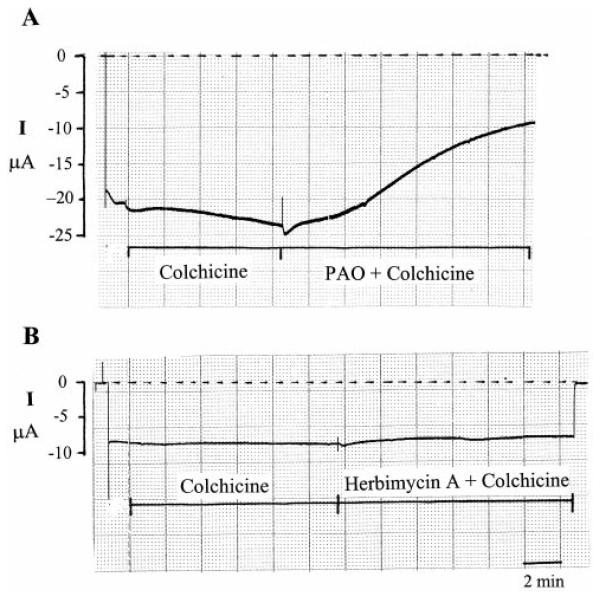

We have also examined the possibility that inhibition of PTP with PAO may attenuate the Golgi-dependent secretory pathway of ROMK1 channels by investigating the effect of PAO in the oocytes treated with 5 μM brefeldin A, an agent that inhibits the exit of proteins from endoplasmic reticulum (22). Addition of brefeldin A had no effect on K+ current within 30 min. Moreover, treatment of brefeldin A did not abolish the inhibitory effect of PAO (data not shown). Because brefeldin A may have no effect on protein recycling (23), we studied the effect of PAO in the presence of colchicine, an agent that inhibits microtubules and microtubule-dependent recycling. Application of 20 μM colchicine had no significant effect on K+ current (Fig. 7A). Moreover, colchicine failed to block the effect of PAO, because PAO reduced the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current by 41 ± 5% (n = 5) in the presence of colchicine. In contrast, blocking microtubules with colchicine abolished the effect of herbimycin A (Fig. 7B), and channel activity was 105 ± 10% of the control value in the presence of colchicine (n = 11) in oocytes coex-pressing ROMK1 and cSrc. This suggests that an intact micro-tubule is required for mediating the effect of inhibiting PTK on channel activity. This notion is further supported by experiments in which pretreatment of oocytes with 10 μM taxol blocked the effect of herbimycin A (data not shown).

FIG. 7. A recording showing the effect of 1 μM PAO + 10 μM colchicine (A) and of 1 μM herbimycin A + colchicine (B) on K+ current.

The zero current is indicated by a dotted line.I, current.

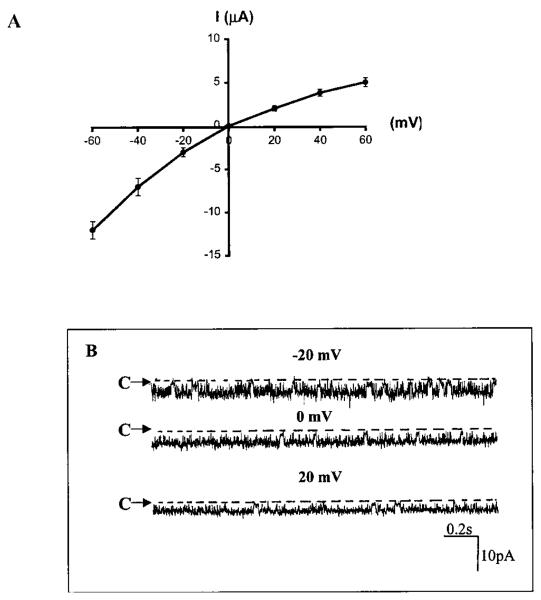

Although the results obtained from the electrophysiological studies strongly suggest that stimulation of PTK increases endocytosis, whereas activation of PTP enhances exocytosis, it does not provide direct evidence to prove the hypothesis. Therefore, we employed laser scanning confocal microscopy to study the effects of PAO and herbimycin A on the membrane distribution of ROMK1 labeled with GFP. We first examined the biophysical properties of GFP-ROMK1 expressed in oocytes. Fig. 8A summarizes results from 10 experiments in which the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current was measured in oocytes expressing GFP-ROMK1. It is apparent that linking GFP to the N terminus of ROMK1 did not affect the expression of ROMK1, because the K+ current (11 ± 1 μA) was similar to that observed in oocytes injected with ROMK1 (14 ± 2 μA; data not shown). Moreover, the current-voltage curve yields a typically weak inward rectifying K+ current. Fig. 8B is a channel recording made in a cell-attached patch from oocytes injected with GFPROMK1. The channel conductance was 38 pS between 0 and 20 mV.

FIG. 8.

A, a current-voltage curve showing the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current measured with a two-electrode voltage clamp in oocytes injected with GFP-ROMK1. The bath solution contained 150 mM KCl. I, current. B, a single channel recording in a cell-attached patch from oocytes injected with GFP-ROMK1. The bath solution contained 145 mM NaCl and 5 mM KCl.

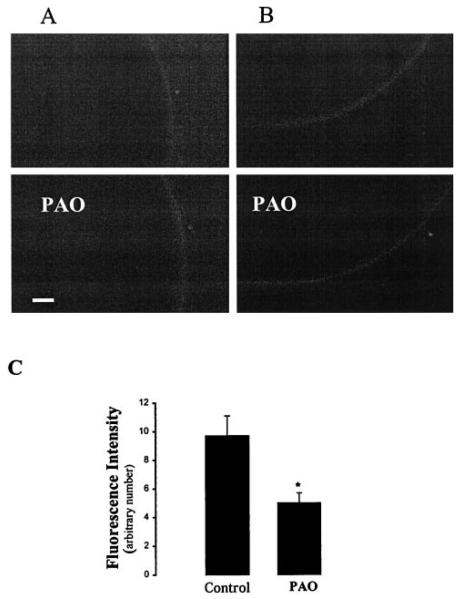

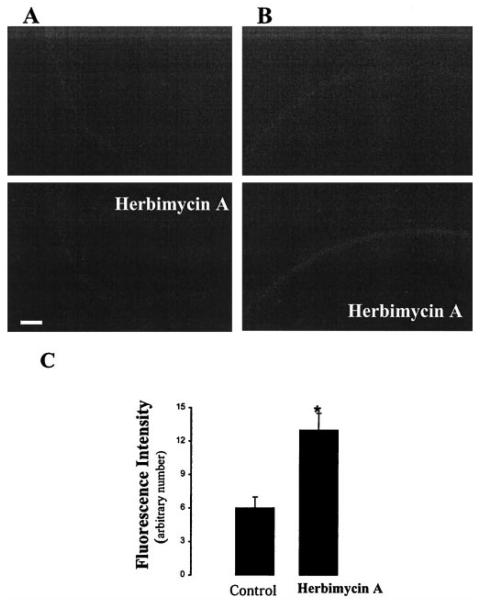

After confirming that GFP-ROMK1 has the same biophysical properties as those of ROMK1, we examined the effects of PTK and PTP inhibitors on ROMK1 location in oocytes expressing GFP-ROMK1 alone or GFP-ROMK1 + cSrc. Fig. 9 is a typical recording from five such experiments in which the effect of PAO (1 μM) on ROMK1 distribution was investigated. Inhibiting PTP did not significantly change the ROMK1 location in oocytes expressing GFP-ROMK1 alone (Fig. 9A). In contrast, PAO significantly decreased the membrane fluorescence intensity (48 ± 5%), an index of the ROMK1 channel density, in the oocytes expressing GFP-ROMK1 and cSrc (Fig. 9, B and C). Fig. 10 is a representative recording showing the effect of herbimycin A on ROMK1 distribution in oocytes injected with GFP-ROMK1 alone (A) and cSrc + GFP-ROMK1 (B). It is apparent that inhibiting PTK increased the membrane density of ROMK1 channels only in oocytes coinjected with cSrc but had no effect in oocytes injected with GFP-ROMK1 alone. Fig. 10C summarizes the results of five such experiments showing that herbimycin A increased the fluorescence intensity by 115 ± 9%.

FIG. 9. The effect of PAO (1 μM) on GFP-ROMK1 distribution in the cell membrane in oocytes expressing GFP-ROMK1 alone (A) or cSrc + GFP-ROMK1 (B).

The top picture was taken immediately after adding PAO (control), and the bottom image was collected 30 min after applying PAO. The bar length represents 60 μm. C, the effect of PAO on the fluorescence intensity of GFP-ROMK1 in the oocyte membrane (arbitrary unit).

FIG. 10. The effect of herbimycin A (1 μM) on GFP-ROMK1 distribution in the cell membrane in oocytes expressing GFPROMK1 alone (A) or cSrc + GFP-ROMK1 (B).

The bar length represents 60 μm. The top image was taken immediately after adding herbimycin A, and the bottom picture was collected 30 min after applying herbimycin A. C, the effect of herbimycin A on the fluorescence intensity of GFP-ROMK1 in the oocyte membrane (arbitrary units).

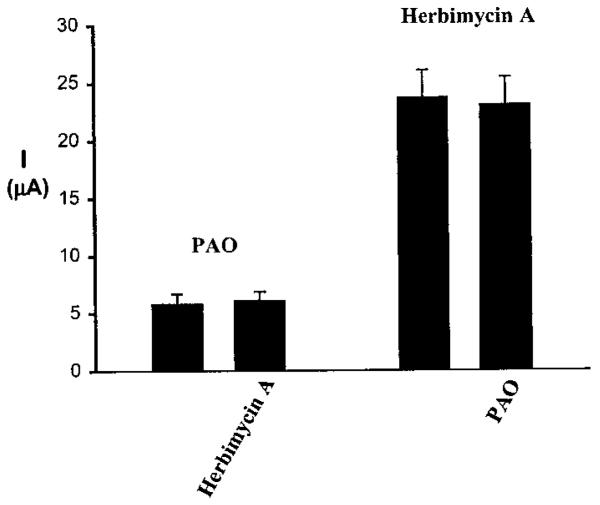

To further explore the role of the interaction between PTK and PTP in regulating ROMK1, we examined the effect of herbimycin A in the oocytes pretreated with PAO and investigated the effect of PAO in the oocytes pretreated with herbimycin A. Fig. 11 shows the effects of herbimycin A and PAO in the oocytes treated with PTP and PTK inhibitors, respectively. We observed that Ba2+-sensitive K+ current in oocytes pre-treated with PAO for 20 min was significantly smaller (5.8 ± 0.9 μA; n = 12) than that in oocytes treated with herbimycin A (23.7 ± 2.4 μA; n = 7). Moreover, PAO failed to reduce the Ba2+-sensitive K+ current (23.1 ± 2.4 μA) in the presence of herbimycin A, whereas herbimycin A had no significant effect on channel activity (6.1 ± 0.9 μA) in the presence of PAO. This strongly suggested that the effect of PAO is the result of stimulating cSrc activity, whereas the effect of herbimycin A resulted from potentiating the effect of PTP.

FIG. 11. The effect of 1 μM PAO or 1 μM herbimycin A on K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 + cSrc.

The oocytes were pretreated with herbimycin A or PAO for 20 min. The current was measured with a two-electrode voltage clamp.I, current.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we found that inhibiting PTK with herbimycin A increases K+ current in oocytes expressing ROMK1 channels and cSrc, whereas blocking PTP with PAO decreases such current. Moreover, we demonstrated that mutation of tyrosine residue 337 to alanine abolished the effects of PAO and herbimycin A on channel activity. This suggests that tyrosine residue 337 is a key site for the action of PTP and PTK. Three lines of evidence support the conclusion that effects of PAO and herbimycin A are the result of inhibiting PTP and PTK, respectively. First, the effect of PAO was absent in the presence of 20% sucrose or concanavalin A, whereas the effect of herbimycin A was blocked by colchicine or taxol. Second, neither PAO nor herbimycin A had an effect on channel activity in inside-out patches.2 Third, pretreatment of oocytes with PAO abolished the stimulatory effect of herbimycin A, whereas herbimycin A treatment completely blocked the inhibitory effect of PAO. Similar results were also observed in the rat CCD, in which pretreatment of the CCD with herbimycin A significantly diminished the effect of PTP inhibitor on the activity of the small conductance K+ channels (16). This supports the notion that inhibition of PTK by herbimycin A enhances PTP-induced dephosphorylation, whereas blocking PTP by PAO potentiates PTK-induced phosphorylation.

Three possible mechanisms could mediate the regulation of ROMK1 by PTK. First, phosphorylating the tyrosine residue of ROMK1 channels could directly inhibit channel activity. Second, tyrosine phosphorylation could block exocytosis of ROMK1 channels and reduce the number of channels on the cell surface. Third, PTK-induced phosphorylation could augment the internalization of ROMK1 channels from the cell membrane.

Relevant to the first possibility are the observations that PTK suppresses delayed rectifying K+ channels, voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv1.3, and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels by direct tyrosine phosphorylation (24-27). Moreover, cSrc has been shown to regulate the N-methyl-d-aspartate channel by direct association and phosphorylation (28). The present study strongly indicates that the phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 337 is essential for the effects of PTK and PTP. However, because addition of exogenous cSrc had no effect on the activity of ROMK1, the hypothesis is not supported that PTK-mediated phosphorylation of ROMK1 or of its associated proteins directly blocks the channel. The results rather suggest that phosphorylation of ROMK1 channels per se does not directly alter the channel gating of ROMK1. It is more likely that tyrosine phosphorylation is a necessary step to activate a signaling cascade that eventually leads to the down-regulation of ROMK1 channels.

Two lines of evidence exclude the second possibility that stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation diminishes exocytosis or recycling of ROMK1 channels. First, application of brefeldin A, an agent that inhibits export of de novo synthesized proteins from endoplasmic reticulum (22), had no effect on ROMK1. Moreover, treatment of cells with brefeldin A did not abolish the effect of PAO. This suggests that stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation by PAO does not affect a brefeldin A-sensitive secretory pathway. Second, treatment with colchicine, an inhibitor of microtubule assembly, or taxol, an agent that “freezes” the microtubule, neither had an effect on channel activity nor abolished the effect of PAO. Because microtubules play an important role in Golgi-independent protein recycling (29), the finding that the effect of PAO was not changed by colchicine or taxol excluded the possibility that stimulating PTK decreases microtubule-dependent recycling.

The observations that the inhibitory effect of PAO was absent in oocytes treated with either 20% sucrose or concanavalin A indicate strongly that stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation increases the internalization of ROMK1 channels. This conclusion is also supported by the observation that GFPROMK1 membrane location diminished significantly by PAO treatment. It is possible that the phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 337 is essential to initiate the internalization of ROMK1 channels. A large body of evidence indicates that tyrosine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation play an important role in the regulation of protein trafficking (20, 30-32). For instance, tyrosine phosphorylation is involved in mediating the insulin-induced exocytosis of glucose transporters, e.g. GLUT4 (30). Moreover, overexpression of cSrc in fibroblasts has been demonstrated to stimulate the endocytosis of epidermal growth factor receptor (31). In this regard, it has been reported that cSrc can interact with actin/filament associate protein, AFAP-110 (32), and phosphorylate actinin in activated platelets (33). In addition, cSrc has been shown to mediate epidermal growth factor-induced clathrin phosphorylation, which is essential for the internalization of epidermal growth factor receptors (34). Finally, in neuronal cells cSrc can interact with dynamin and synapsin, which are involved in vesicle trafficking (35).

In contrast to the effect of PAO, the finding that pretreatment of the oocytes with taxol or colchicine completely abolished the effect of herbimycin A suggests that stimulation of tyrosine dephosphorylation increases exocytosis of ROMK1. Moreover, the experimental results with confocal microscopy also confirmed that herbimycin A increased the GFP-ROMK1 density in the cell membrane. Because microtubules have been shown to be involved in regulating protein trafficking (29), it is conceivable that increasing tyrosine dephosphorylation enhances the microtubule-dependent exocytosis of the ROMK1 channel. Moreover, the finding that colchicine and taxol did not block the effect of PAO suggests that microtubules may not be involved in modulating the endocytosis of ROMK1 channels. Relevant to the present observation is the finding that the cytoskeleton plays a key role in the exocytotic recruitment of GLUT4 (a glucose transporter) to the plasma membrane from an intracellular pool, but not in endocytosis (36).

The physiological significance of PTK-induced regulation of ROMK1 channels has been previously documented. It is well established that dietary K+ intake plays an important role in the regulation of renal K+ secretion (15, 37). Because the ROMK1-like channel is the main K+ channel located in the apical membrane of the CCD, alteration in ROMK1 channel activity should have a significant impact on renal K+ secretion. We and others have observed that the number of the small conductance K+ channel is almost 5–6 times higher in the CCD obtained from rats on a high K+ diet than that on a K+-deficient diet (17, 37). The effect of high K+ intake on channel activity was not the result of increasing the circulating aldosterone level, because aldosterone perfusion failed to stimulate the activity of the small conductance K+ channel in the CCD (37). We have previously reported that the activity and concentration of cSrc, a nonreceptor type of PTK, were significantly higher in the renal cortex from rats on a K+-deficient diet than those from rats on a high K+ diet (17). We have suggested that a low K+ intake increases the expression and activity of PTK, which in turn decreases the number of the apical small conductance K+ channel and suppresses K+ secretion. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that inhibition of PTK increased the number of the small conductance K+ channel in the CCD from animals on a K+-deficient diet (17). Furthermore, we have also shown that inhibition of PTP reduced the number of the small conductance K+ channel in the CCD from rats on a high K+ diet (16).

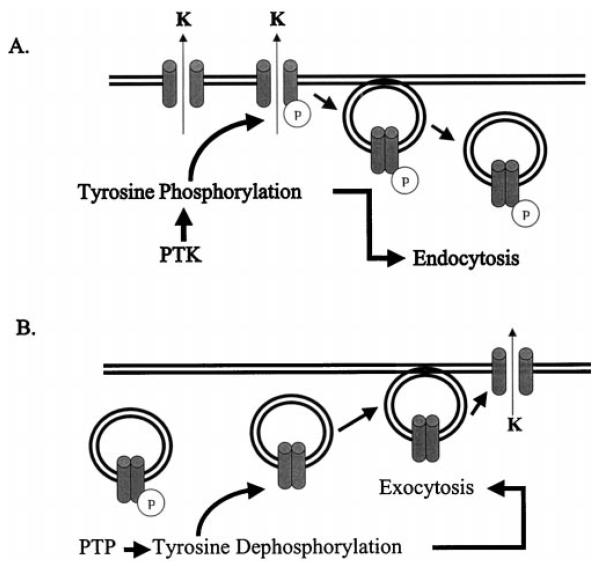

Although the present study strongly suggests that tyrosine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation regulate the endocytosis and exocytosis of ROMK1 channels, the mechanism by which the interaction between PTK and PTP regulates ROMK1 channel trafficking is not completely understood. It is possible that phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 337 of the ROMK1 channel creates a binding site for proteins that are involved in ROMK1 trafficking. Further experiments are required to detect these proteins that interact with the phosphorylated ROMK1 channels. Fig. 12 is a simple model illustrating the mechanism of the PTK-PTP interaction. An increase in tyrosine phosphorylation reduces the channel activity by endocytosis of ROMK1 channels, whereas stimulation of tyrosine dephosphorylation increases the number of ROMK1 channels by exocytosis.

FIG. 12.

A cell model illustrating the mechanisms by which PTK (A) and PTP (B) regulate ROMK1 channels.

We conclude that the balance between PTK and PTP activity plays an important role in the regulation of ROMK1 channels and that tyrosine residue 337 of the ROMK1 channel is the key site for the effects of PTP and PTK. The effects of PTK and PTP on channel activity are achieved by regulating the retrieval or insertion of ROMK1-like channels into the apical membrane of principal cells in the CCD.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. L. G. Palmer for constructive comments during the course of the experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK 47402 and DK 54983 (to W.-H. W.), DK 17433 (to G. G.), and DK 37605 (to S. C. H.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: CCD, cortical collecting duct; PTP, protein-tyrosine phosphatase; PTK, protein-tyrosine kinase; PAO, phenylarsine oxide; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

W.-H. Wang, unpublished observation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palmer LG, Choe H, Frindt G. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:F404–F410. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.3.F404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho K, Nichols CG, Lederer WJ, Lytton J, Vassilev PM, Kanazirska MV, Hebert SC. Nature. 1993;362:31–38. doi: 10.1038/362031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang WH, Hebert SC, Giebisch G. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:413–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fakler B, Schultz JH, Yang J, Schulte U, Braendle U, Zenner HP, Jan LY, Ruppersberg J. EMBO J. 1996;15:4093–4099. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang WH, Giebisch G. J. Gen. Physiol. 1991;98:35–61. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang WH, Giebisch G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:9722–9725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macica CM, Yang YH, Lerea K, Hebert SC, Wang WH. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:F175–F181. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.1.F175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNicholas CM, Wang W, Ho K, Hebert SC, Giebisch G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:8077–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacGregor GG, Xu JZ, McNicholas CM, Giebisch G, Hebert SC. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:F415–F422. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.3.F415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu ZC, Yang Y, Hebert SC. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9313–9319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNicholas CM, Guggino WB, Schwiebert EM, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Egan ME. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:8083–8088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruknudin A, Schulze DH, Sullivan SK, Lederer WJ, Welling PA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14165–14171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, Wang WH, Klein-Robbenhaar G, Giebisch G. Renal Physiol. Biochem. 1995;18:169–182. doi: 10.1159/000173914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boim MA, Ho K, Schuck ME, Bienkowski MJ, Block JH, Slightom JL, Yang Y, Brenner BM, Hebert SC. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:F1132–F1140. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.6.F1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giebisch G. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:F817–F833. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.5.F817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Y, Bloom P, Gu RM, Wang WH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20502–20507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang WH, Lerea KM, Chan M, Giebisch G. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;278:F165–F171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macica CM, Yang YH, Hebert SC, Wang WH. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:F588–F594. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begum N. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:E14–E23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.1.E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luttrell LM, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luttrell LM, Daaka Y, Della-Rocca GJ, Lefkowitz RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31648–31656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chardin P, McCormick F. Cell. 1999;97:153–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller SG, Carnell L, Moore HPH. J. Cell Biol. 1992;118:267–283. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang XY, Morielli AD, Peralta EG. Cell. 1993;75:1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90324-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobko A, Peretz A, Attali B. EMBO J. 1998;17:4723–4734. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prevarskaya NB, Skryma RN, Vacher P, Daniel N, Djiane J, Dufy B. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:24292–24299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowlby MR, Fadool DA, Holmes TC, Levitan IB. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;110:601–610. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu XM, Askalan R, Kei GJ, II, Salter MW. Science. 1997;275:674–678. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamm-Alvarez SF, Sheets MP. Physiol. Rev. 1998;78:1109–1129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pessin JE, Thurmond DC, Elmendorf JS, Coker KJ, Okada S. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2593–2596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware MF, Tice DA, Parsons SJ, Lauffenburger DA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30185–30190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guappone AC, Flynn D/C. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1997;175:243–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1006840104666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izaguirre C, Aguirre L, Ji P, Aneskievich B, Haimovich B. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:37012–37020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilde A, Beattie EC, Lem L, Riethof DA, Liu SH, Mobley WC, Soriano P, Brodsky FM. Cell. 1999;96:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster-Barber A, Bishop M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:4673–4677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omata W, Shibata H, Li L, Takata K, Kojima I. Biochem. J. 2000;346:321–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer LG, Antonian L, Frindt G. J. Gen. Physiol. 1994;105:693–710. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.4.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]