Abstract

Many strategies used to kill cancer cells induce stress-responses that activate survival pathways to promote emergence of a treatment resistant phenotype. Secretory clusterin (sCLU) is a stress-activated cytoprotective chaperone up-regulated by many varied anti-cancer therapies to confer treatment resistance when over-expressed. sCLU levels are increased in several treatment recurrent cancers including castrate resistant prostate cancer, and therefore has become an attractive target in cancer therapy. sCLU is not druggable with small molecule inhibitors, and so nucleotide-based strategies to inhibit sCLU at the RNA level are appealing. Preclinical studies have shown that antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) or siRNA knockdown of sCLU have preclinical activity in combination with hormone- and chemotherapy. Phase I and II clinical trial data indicates that the second generation ASO, Custirsen (OGX-011) has biologic and clinical activity, suppressing sCLU expression in prostate cancer tissues by more than 90%. A randomized study comparing docetaxel-Custirsen to docetaxel alone in men with castrate resistant prostate cancer reported improved survival by 7 months from 16.9 to 23.8 months. Strong preclinical and clinical proof-of-principle data provides rationale for further study of sCLU inhibitors in randomized phase III trials, which are planned to begin in 2010.

Background

Development of treatment resistance is a common feature of solid tumor malignancies and the underlying basis for most cancer deaths. Treatment resistance results from multiple, stepwise changes in DNA structure and gene expression - a Darwinian interplay of genetic and epigenetic factors arising, in part, from selective pressures of treatment. In most solid tumors this evolutionary process cannot be attributed to singular genetic events, involving instead many cumulative changes in gene structure and expression that facilitate cancer cell growth and survival. Examples include altered expression of genes regulating drug penetration, transport, and metabolism (1), or those regulating the apoptotic rheostat of cancer cells. In advanced prostate cancer, for example, treatment resistance is manifest by progression to castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) via mechanisms attributed to re-activation of androgen receptor axis (2), alternative mitogenic growth factor pathways (3–5), and stress-induced pro-survival gene (6–8) and cytoprotective chaperone networks (9, 10).

Molecular chaperones, including heat-shock proteins (Hsps), help cells cope with stress-induced protein misfolding, aggregation and denaturation and play prominent roles in cellular signaling and transcriptional regulatory networks. Chaperones act as genetic buffers stabilizing the phenotype of various cells and organisms at times of environmental stress, enhancing the Darwinian fitness of cells during transformation, progression, and treatment resistance (11). Indeed, the heat shock response is a highly conserved protective mechanism for eukaryotic cells under stress, and is associated with oncogenic transformation, proliferation, survival, and thermotolerance (12). Thus, targeting molecular chaperones with multifunctional roles in endoplasmic reticular (ER) stress and cellular signaling and transcriptional regulatory networks associated with cancer progression and treatment resistance is an attractive and rational therapeutic strategy. Of special relevance to treatment-resistant cancers are those chaperones up-regulated anti-cancer therapies that function to inhibit treatment-induced cell death, including clusterin (CLU) (10, 13) and Hsp27 (9, 14). This review summarizes the roles of CLU in cancer cell survival and treatment resistance, and the preclinical pharmacology and early clinical trial results for custirsen (OGX-011), a second generation antisense inhibitor targeting CLU.

CLU Structure and Function

Secretory CLU (sCLU) is a multifunctional, stress-induced, ATP-independent molecular chaperone, previously known as apolipoprotein J, testosterone-repressed prostate message-2, ionizing radiation-induced protein-8, SP 40–40, complement lysis inhibitor, gp80, glycoprotein III, or sulphate glycoprotein-2. sCLU is expressed in most tissues and human fluids analyzed. sCLU is a versatile molecular chaperone containing amphipathic and coiled-coil helices in addition to large intrinsic disordered regions. These properties of sCLU resemble survival chaperones associated with tissue injury and pathology like acute phase protein haptoglobin (15) and small Hsp’s (16). Indeed, sCLU is involved in many biological processes ranging from mammary and prostate gland involution to amyloidosis and neurodegenerative disease, as well as cancer progression and treatment resistance (17).

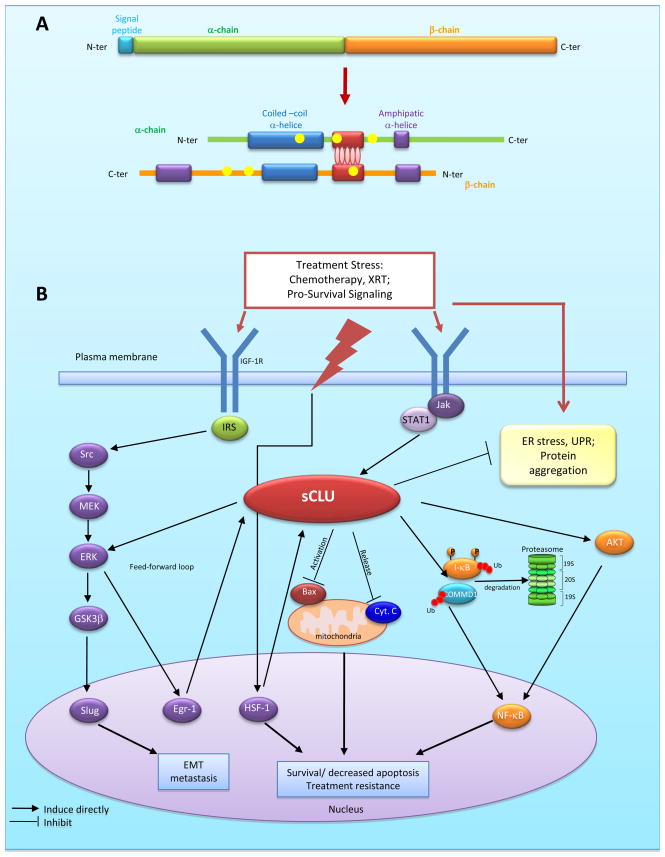

CLU is a single copy gene, organized into 9 exons (8 introns) and a 5′-untranslated region, located on chromosome 8p21-p12 extending over 16 kb (18). In humans, CLU gene codes for two secretory isoforms (sCLU-1, sCLU-2) originating from transcriptional start sites in exons 1 and 2, respectively; only sCLU-2 is expressed in sub-primates. sCLU is an ER-targeted, 449-aa polypeptide that represents the predominant translation product of the human gene (Figure 1A). Proteolytic removal of the ER-targeting signal peptide produces a 60 kDa ER-associated, high mannose, cytoplasmic form (sCLUc) (19). sCLUc is further glycosylated in the Golgi and cleaved at Arg227-Ser228 into two 40 kDa α- and β-subunits. These subunits are assembled in an anti-parallel manner into a ~80 kDa mature, secreted, heterodimeric form (sCLUs), in which its cysteine-rich centers are linked by 5 disulfide bridges and flanked by two coiled coil α-helices and three predicted amphipathic α-helices. The coiled-coil domain is a highly versatile protein folding and oligomerization motif, facilitating its interaction with client proteins involved in many protein signal-transducing events. While sCLU is cytoprotective and anti-apoptotic, a pro-apoptotic activity ~55 kDa nuclear (nCLU) splice variant lacking exon II and the ER signal peptide has been described (20, 21).

Fig. 1.

A, CLU Structure: The cytoplasmic precursor peptide (sCLUc) is cleaved proteolytically between amino acids 22/23 to remove the signal peptide (Turquoise) and between residues 227/228 to generate the α (green) and β (orange) chains. The α and β chains are assembled in anti-parallel to form a mature heterodimer (sCLUs). The cysteine rich centers (red) are linked by 5 disulfide bridges (red ellipses). These are flanked by two predicted coiled-coil α-helices (blue) and 3 predicted amphipathic α-helices (purple). 6 N-glycosylation sites are indicated as yellow dots. B, Role of CLU in cancer progression. sCLU is up-regulated by stress-activated transcription factors (eg. HSF-1), with ER stress, and downstream of cytokines (via JAK/stat) and IGF-1R (via Src-MEK-ERK-Erg-1) signaling pathways. Once up-regulated, CLU exerts a feed-forward loop involving ERK activation which lead to GSK-3β phosphorylation and Slug activation. Up-regulation of CLU increases p-AKT levels, facilitating downstream cascades that include NFκB. CLU increases cell survival through mechanisms involving inhibition of ER stress, suppressing Bax activation with mitochondrial sequestration of cytochrome C, and NF-κB nuclear translocation by enhancing proteasomal degradation of I-κB and COMMD1.

Promoter sequences of CLU gene are conserved during evolution, and include stress-associated sites like activator-protein-1 (AP-1), AP-2, SP-1 (stimulatory element), HSE (heat shock element), CRE (cAMP response element), and a “CLU-specific element” (CLE) recognized by HSF-1/HSF-2 heterocomplexes (22). Steroid response elements include GRE (glucocorticoid response element) (23–25) and androgen response element (ARE) sites (26). CLU promoter regions contain CpG-rich methylation domains (23, 27) indicating CLU may be regulated by DNA methylation and histone acetylation (28); indeed, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine significantly increases sCLU expression in prostate cancer cells (29). Additionally, sCLU expression increases downstream of survival signaling pathways, including IGF-1 via Src-Mek-Erk-EGR-1 (30) and cytokines via Jak/STAT1 (31) (Figure 1B).

sCLU functions to protect cells from many varied therapeutic stressors that induce apoptosis, including androgen or estrogen withdrawal, radiation, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and biologic agents (32). Mechanisms by which sCLU exerts these effects are not fully elucidated. Because sCLU binds to a wide variety of biological ligands, and is regulated by HSF1 (22), an emerging view suggests that sCLU functions like small HSPs to chaperone and stabilize conformations of proteins at times of cell stress. Indeed, sCLU is more potent than other Hsp’s at inhibiting stress-induced protein precipitation. As a functional homologue of sHsp’s, CLU has chaperone activity with a potent ability to influence the amorphous and fibrillar aggregation of many different proteins. CLU inhibits stress-induced protein aggregation by binding to exposed regions of hydrophobicity on non-native proteins to form soluble, high molecular mass complexes (33, 34). During amorphous aggregation of proteins, sCLU interacts with slowly aggregating species on the off-folding pathway. Immunoaffinity depletion of CLU from human plasma renders proteins in this fluid more susceptible to aggregation and precipitation (35). sCLUs interacts with stressed cell surface proteins (e.g. receptors) to inhibit pro-apoptotic signal transduction (16). sCLUc inhibits ER stress, retro-translocating from the ER to the cytosol to inhibit aggregation of intracellular proteins and prevent apoptosis (36). Interestingly, and likely related to its role in inhibiting protein aggregation, sCLU is the most abundant protein associated with β-amyloid deposits in Alzheimers (33). Collectively, the preceding indicates sCLU plays an important role in unfolded protein and ER stress responses.

Many reports also document that sCLUc inhibits mitochondrial apoptosis. For example, sCLUc suppresses p53-activating stress signals and stabilizes cytosolic Ku70-Bax protein complex to inhibit Bax activation (37). sCLUc specifically interacts with conformationally-altered Bax to inhibit apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic drugs (38). sCLU knockdown alters the ratios of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, disrupting Ku70/Bax complexes and Bax activation (37, 38). In addition, sCLUc increases Akt phosphorylation levels and cell survival rates (39). sCLU induces epithelial-mesenchymal transformation by increasing Smad2/3 stability and enhancing TGF-β-mediated Smad transcriptional activity (40). sCLUc also promotes prostate cancer cell survival by increasing NF-κB nuclear transactivation, acting as a ubiquitin-binding protein that enhances COMMD1 and I-kB proteasomal degradation via interaction with E3 ligase family members (60). sCLU knockdown stabilized COMMD1 and I-κB, suppressing NF-κB translocation to the nucleus, and suppressing NF-κB-regulated gene signatures (Figure 1B).

Clinical-Translational Advances

CLU is expressed in many human cancers, including breast, lung, bladder, kidney, colon-rectum and prostate (41–45). In prostate, sCLU was originally cloned as “testosterone-repressed prostate message 2” (TRPM-2) (46) from regressing rat prostate, but was later defined as a stress-activated and apoptosis-associated, rather than an androgen-repressed, gene (10). sCLU levels increase following castration and in castrate resistant prostate cancer models (10, 13). In human prostate cancer, sCLU levels are low in low grade untreated hormone-naive tissues, but increase with higher gleason score (47) and within weeks after androgen deprivation (48). sCLU expression correlates with loss of the tumor suppressor gene Nkx3.1 during the initial stages of prostate tumorigenesis in Nkx3.1 knockout mice (49). Interestingly, high levels of sCLU expression associate with migration, invasion and metastasis, while sCLU silencing induces Mesenchymal-Epithelial-Transition via inhibition of Slug (50). Experimental and clinical studies associate sCLU with development treatment resistance, where sCLU suppresses treatment-induced cell death in response to androgen withdrawal, chemotherapy or radiation (10, 13, 48). Over-expression of sCLU in human prostate LNCaP cells accelerates progression after hormone- or chemotherapy (13), identifying sCLU as a anti-apoptotic gene up-regulated by treatment stress that confers therapeutic resistance when over-expressed.

sCLU is not a traditional druggable target and can only be targeted at mRNA levels. An antisense inhibitor targeting the translation initiation site of human exon II CLU (OGX-011) was developed at the University of British Columbia and out-licensed to OncoGeneX Pharmaceuticals Inc. OGX-011, or Custirsen, is a second-generation antisense oligonucleotide with a long tissue half-life of ~7 days that potently suppresses sCLU levels in vitro and in vivo. OGX-011 improved the efficacy of chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone withdrawal by inhibiting expression of sCLU and enhancing apoptotic rates in pre-clinical xenograft models of prostate, lung, renal cell, breast and other cancers (51–53).

To date, over 300 patients have been treated with Custirsen in 6 phase I and II clinical trials. The first-in-human phase I study with Custirsen used a novel neoadjuvant design to identify effective biologic dosing of Custirsen to inhibit sCLU expression in human cancer (54). In this dose-escalation study, cohorts of 3–6 patients with localized prostate carcinoma and high risk features were treated with Custirsen in doses of up to 640 mg given as a 2-hour intravenous infusion on Days 1, 3, 5, 8, 15, 22 and 29 with prostatectomy performed within 7 days of the last OGX-011 dose. Neoadjuvant androgen deprivation was administered concurrently. The presurgery design was used to correlate changes in expression of sCLU to drug dose received and drug levels within the prostate tissue itself. In this study, treatment was well tolerated and at doses of 320 mg and higher, concentrations of full-length Custirsen were achieved that were associated with preclinical activity. Mean tissue concentrations increased in a dose-dependent manner to 4.82 μg/g of prostate tissue at 640 mg dose, corresponding to a concentration of 644 nM. Custirsen produced statistically significant, dose-dependent >90% knockdown of sCLU in normal and tumor tissue. Furthermore, mean apoptotic indices increased from 7.1% to 21.2%. Thus, clinical pharmacodynamic data clearly indicate that Custirsen is biologically active in humans and identified 640 mg as the optimal biologic dose for Phase II trials.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters have been similar across phase I studies including when Custirsen was combined with chemotherapy and decreases in serum sCLU have been consistently observed (55, 56). A phase II trial of 85 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with combined Custirsen and gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy (56) reported an objective response rate of 23% and median overall survival of 383 days with 58% surviving >1 year. This overall survival data was considered clinically significant as compared to prior clinical trials data with chemotherapy alone, justifying further studies in NSCLC.

Randomized phase II studies were conducted in patients with castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) because of limitations in interpreting anti-tumor responses of novel biologics when combined with chemotherapy (57). 81 patients with chemo-naïve, metastatic CRPC were randomized to receive either docetaxel-Custirsen or docetaxel-alone. The median cycles delivered for docetaxel-Custirsen was 9 compared to 7 for docetaxel-alone. There was evidence of biologic effect with 18% decrease in mean serum sCLU in patients treated with docetaxel-Custirsen versus 8% increase in controls (P=0.0005). Median progression free survival was 7.3 months for docetaxel-Custirsen and 6.1 months for docetaxel-alone arm. Median overall survival on the docetaxel-Custirsen arm was 23.8 months, ~7 months longer than those receiving docetaxel-alone (16.9 months). Multivariate analysis of factors associated with improved overall survival identified ECOG performance status of 0 (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 0.28, P < 0.0001), and treatment assignment to the docetaxel-Custirsen treatment arm (HR = 0.49, P = 0.012). Given the survival outcomes observed in the docetaxel-Custirsen arm, further evaluation of the combination is warranted in comparative randomized phase 3 studies.

Another trial of docetaxel-recurrent CRPC randomized 42 patients to receive either docetaxel or mitoxantrone both combined with Custirsen, thus evaluating the hypotheses that Custirsen could reverse docetaxel resistance or improve mitoxantrone efficacy in a chemo-resistant population (58). PSA declines of ≥30% were seen in 55% of docetaxel-Custirsen patients and 32% of mitoxantrone-Custirsen patients. Pain responses were also seen in >50% of patients and after a median follow-up of 13.3 months, 60% of patients were alive in both arms. These results are also of interest considering PSA response rates of <20% and median survival <12 months is usually reported in patients with docetaxel-resistant CRPC receiving second-line chemotherapy (59), supporting further studies second line indications for CRPC.

In summary, sCLU is a stress-activated cytoprotective chaperone that confers broad-spectrum treatment resistance when over-expressed. Preclinical and randomized clinical data with Custirsen confirms potent suppression of sCLU expression and prolonged overall survival in CRPC. Further studies of Custirsen in randomized phase III trials are justified and are due to begin in 2010.

References

- 1.Huang Y, Anderle P, Bussey KJ, et al. Membrane transporters and channels: role of the transportome in cancer chemosensitivity and chemoresistance. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4294–301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen KE, Scher HI. Starving the addiction: new opportunities for durable suppression of AR signaling in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):4792–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyake H, Nelson C, Rennie PS, Gleave ME. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 helps accelerate progression to androgen-independence in the human prostate LNCaP tumor model through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2000;141(6):2257–65. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culig Z. Androgen receptor cross-talk with cell signalling pathways. Growth Factors. 2004;22(3):179–84. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(3):280–5. doi: 10.1038/6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleave M, Tolcher A, Miyake H, et al. Progression to androgen independence is delayed by adjuvant treatment with antisense Bcl-2 oligodeoxynucleotides after castration in the LNCaP prostate tumor model. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(10):2891–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyake H, Tolcher A, Gleave ME. Antisense Bcl-2 oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit progression to androgen-independence after castration in the Shionogi tumor model. Cancer Res. 1999;59(16):4030–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miayake H, Tolcher A, Gleave ME. Chemosensitization and delayed androgen-independent recurrence of prostate cancer with the use of antisense Bcl-2 oligodeoxynucleotides. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(1):34–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocchi P, So A, Kojima S, et al. Heat shock protein 27 increases after androgen ablation and plays a cytoprotective role in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6595–602. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyake H, Nelson C, Rennie PS, Gleave ME. Testosterone-repressed prostate message-2 is an antiapoptotic gene involved in progression to androgen independence in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(1):170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitesell L, Lindquist SL. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(10):761–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell. 2007;130(6):1005–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake H, Nelson C, Rennie PS, Gleave ME. Acquisition of chemoresistant phenotype by overexpression of the antiapoptotic gene testosterone-repressed prostate message-2 in prostate cancer xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2000;60(9):2547–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocchi P, Beraldi E, Ettinger S, et al. Increased Hsp27 after androgen ablation facilitates androgen-independent progression in prostate cancer via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-mediated suppression of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(23):11083–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yerbury JJ, Rybchyn MS, Easterbrook-Smith SB, Henriques C, Wilson MR. The acute phase protein haptoglobin is a mammalian extracellular chaperone with an action similar to clusterin. Biochemistry. 2005;44(32):10914–25. doi: 10.1021/bi050764x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carver JA, Rekas A, Thorn DC, Wilson MR. Small heat-shock proteins and clusterin: intra- and extracellular molecular chaperones with a common mechanism of action and function? IUBMB Life. 2003;55(12):661–8. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001640498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleave M, Miyake H, Zangemeister-Wittke U, Jansen B. Antisense therapy: current status in prostate cancer and other malignancies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2002;21(1):79–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1020172424152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong P, Borst DE, Farber D, et al. Increased TRPM-2/clusterin mRNA levels during the time of retinal degeneration in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. Biochem Cell Biol. 1994;72(9–10):439–46. doi: 10.1139/o94-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakins J, Bennett SA, Chen JH, et al. Clusterin biogenesis is altered during apoptosis in the regressing rat ventral prostate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(43):27887–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Zhou W, Kundu S, et al. The leader sequence triggers and enhances several functions of clusterin and is instrumental in the progression of human prostate cancer in vivo and in vitro. BJU international. 2006;98(2):452–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leskov KS, Klokov DY, Li J, Kinsella TJ, Boothman DA. Synthesis and functional analyses of nuclear clusterin, a cell death protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):11590–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loison F, Debure L, Nizard P, le Goff P, Michel D, le Drean Y. Up-regulation of the clusterin gene after proteotoxic stress: implication of HSF1-HSF2 heterocomplexes. Biochem J. 2006;395(1):223–31. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosemblit N, Chen CL. Regulators for the rat clusterin gene: DNA methylation and cis-acting regulatory elements. J Mol Endocrinol. 1994;13(1):69–76. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0130069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong P, Pineault J, Lakins J, et al. Genomic organization and expression of the rat TRPM-2 (clusterin) gene, a gene implicated in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(7):5021–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel D, Chatelain G, North S, Brun G. Stress-induced transcription of the clusterin/apoJ gene. Biochem J. 1997;328 (Pt 1):45–50. doi: 10.1042/bj3280045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cochrane DR, Wang Z, Muramaki M, Gleave ME, Nelson CC. Differential regulation of clusterin and its isoforms by androgens in prostate cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(4):2278–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong P, Taillefer D, Lakins J, Pineault J, Chader G, Tenniswood M. Molecular characterization of human TRPM-2/clusterin, a gene associated with sperm maturation, apoptosis and neurodegeneration. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221(3):917–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakao M. Epigenetics: interaction of DNA methylation and chromatin. Gene. 2001;278(1–2):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rauhala HE, Porkka KP, Saramaki OR, Tammela TL, Visakorpi T. Clusterin is epigenetically regulated in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(7):1601–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Criswell T, Beman M, Araki S, et al. Delayed activation of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor/Src/MAPK/Egr-1 signaling regulates clusterin expression, a pro-survival factor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):14212–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallman DA, Chen X, Zhong B, et al. Clusterin mediates TRAIL resistance in prostate tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(11):2938–47. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zellweger T, Miyake H, July LV, Akbari M, Kiyama S, Gleave ME. Chemosensitization of human renal cell cancer using antisense oligonucleotides targeting the antiapoptotic gene clusterin. Neoplasia. 2001;3(4):360–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yerbury JJ, Poon S, Meehan S, et al. The extracellular chaperone clusterin influences amyloid formation and toxicity by interacting with prefibrillar structures. FASEB J. 2007;21(10):2312–22. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7986com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochgrebe TT, Humphreys D, Wilson MR, Easterbrook-Smith SB. A reexamination of the role of clusterin as a complement regulator. Exp Cell Res. 1999;249(1):13–21. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poon S, Rybchyn MS, Easterbrook-Smith SB, Carver JA, Pankhurst GJ, Wilson MR. Mildly acidic pH activates the extracellular molecular chaperone clusterin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39532–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nizard P, Tetley S, Le Drean Y, et al. Stress-induced retrotranslocation of clusterin/ApoJ into the cytosol. Traffic. 2007;8(5):554–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trougakos IP, Lourda M, Antonelou MH, et al. Intracellular clusterin inhibits mitochondrial apoptosis by suppressing p53-activating stress signals and stabilizing the cytosolic Ku70-Bax protein complex. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(1):48–59. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, Kim JK, Edwards CA, Xu Z, Taichman R, Wang CY. Clusterin inhibits apoptosis by interacting with activated Bax. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(9):909–15. doi: 10.1038/ncb1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ammar H, Closset JL. Clusterin activates survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(19):12851–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee KB, Jeon JH, Choi I, Kwon OY, Yu K, You KH. Clusterin, a novel modulator of TGF-beta signaling, is involved in Smad2/3 stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(4):905–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redondo M, Villar E, Torres-Munoz J, Tellez T, Morell M, Petito CK. Overexpression of clusterin in human breast carcinoma. The American journal of pathology. 2000;157(2):393–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64552-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyake H, Gleave M, Kamidono S, Hara I. Overexpression of clusterin in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder is related to disease progression and recurrence. Urology. 2002;59(1):150–4. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake H, Hara S, Arakawa S, Kamidono S, Hara I. Over expression of clusterin is an independent prognostic factor for nonpapillary renal cell carcinoma. The Journal of urology. 2002;167(2 Pt 1):703–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen X, Halberg RB, Ehrhardt WM, Torrealba J, Dove WF. Clusterin as a biomarker in murine and human intestinal neoplasia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(16):9530–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233633100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg J, Oyasu R, Lang S, et al. Intracellular levels of SGP-2 (Clusterin) correlate with tumor grade in prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research. 1997;3(10):1707–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montpetit ML, Lawless KR, Tenniswood M. Androgen-repressed messages in the rat ventral prostate. Prostate. 1986;8(1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990080105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinberg J, Oyasu R, Lang S, et al. Intracellular levels of SGP-2 (Clusterin) correlate with tumor grade in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(10):1707–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.July LV, Akbari M, Zellweger T, Jones EC, Goldenberg SL, Gleave ME. Clusterin expression is significantly enhanced in prostate cancer cells following androgen withdrawal therapy. Prostate. 2002;50(3):179–88. doi: 10.1002/pros.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song H, Zhang B, Watson MA, Humphrey PA, Lim H, Milbrandt J. Loss of Nkx3.1 leads to the activation of discrete downstream target genes during prostate tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(37):3307–19. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chou TY, Chen WC, Lee AC, Hung SM, Shih NY, Chen MY. Clusterin silencing in human lung adenocarcinoma cells induces a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition through modulating the ERK/Slug pathway. Cell Signal. 2009;21(5):704–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyake H, Hara I, Gleave ME. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide therapy targeting clusterin gene for prostate cancer: Vancouver experience from discovery to clinic. Int J Urol. 2005;12(9):785–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sowery RD, Hadaschik BA, So AI, et al. Clusterin knockdown using the antisense oligonucleotide OGX-011 re-sensitizes docetaxel-refractory prostate cancer PC-3 cells to chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2008;102(3):389–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gleave M, Miyake H. Use of antisense oligonucleotides targeting the cytoprotective gene, clusterin, to enhance androgen- and chemo-sensitivity in prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2005;23(1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chi KN, Eisenhauer E, Fazli L, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of OGX-011, a 2′-methoxyethyl antisense oligonucleotide to clusterin, in patients with localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(17):1287–96. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chi KN, Siu LL, Hirte H, et al. A Phase I Study of OGX-011, a 2′-Methoxyethyl Phosphorothioate Antisense to Clusterin, in Combination with Docetaxel in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Clinical cancer research. 2008;14(3):833–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laskin J, Hao D, Canil C, et al. A phase I/II study of OGX-011 and a gemcitabine (GEM)/platinum regimen as first-line therapy in 85 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(S18):7596. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chi KN, Hotte SJ, Yu E, et al. Mature results of a randomized phase II study of OGX-011 in combination with docetaxel/prednisone versus docetaxel/prednisone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(15s) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8771. Abstract 5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saad F, Hotte SJ, North SA, et al. A phase II randomized study of custirsen (OGX-011) combination therapy in patients with poor-risk hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) who relapsed on or within six months of 1st-line docetaxel therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(15S):5002. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michels J, Montemurro T, Murray N, Kollmannsberger C, Chi KN. First- and second-line chemotherapy with docetaxel or mitoxantrone in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: does sequence matter? Cancer. 2006;106(5):1041–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zoubeidi A, Ettinger S, Beraldi E, et al. Clusterin facilitates COMMD1 and I-kB degradation to enhance NF-kB activity in prostate cancer cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0277. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]