Abstract

mRNA profiling is routinely used to identify microRNA targets, however, this high-throughput technology is not suitable for identifying targets regulated only at protein level. Here, we have developed and validated a novel methodology based on computational analysis of promoter sequences combined with mRNA microarray experiments to reveal transcription factors that are direct microRNA targets at the protein level. Using this approach we identified Smad3, a key transcription factor in the TGFβ signaling pathway, as a direct miR-140 target. We showed that miR-140 suppressed the TGFβ pathway through repression of Smad3 and that TGFβ suppressed the accumulation of miR-140 forming a double negative feedback loop. Our findings establish a valid strategy for the discovery of microRNA targets regulated only at protein level, and we propose that additional targets could be identified by re-analysis of existing microarray datasets.

Keywords: microRNA-140, microRNA target identification, Smad, TGFβ

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short (21–24 nucleotides [nt]) noncoding RNAs that regulate the expression of protein coding genes (Bartel 2004). miRNAs guide RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to mRNAs if the miRNA can anneal to the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of the mRNA. Normally the complementarity between miRNA and the 3′ UTR is not perfect for the entire length of the miRNA, although the seed sequence of the miRNA (nucleotides in positions 2–9) often displays perfect complementarity to the mRNA (Sethupathy et al. 2006). However, the 3′ half of the miRNA can compensate for any mismatches between mRNA and miRNA in the seed region (Brennecke et al. 2005). Due to the imperfect match between mRNA and miRNAs, RISC does not cleave the mRNA at the target site, but causes translational suppression (Bartel 2004). Additionally, the accumulation level of many, but not all, mRNAs is decreased by miRNAs due to de-adenylation and/or decapping (Rehwinkel et al. 2005; Behm-Ansmant et al. 2006; Giraldez et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006; Eulalio et al. 2007; Eulalio et al. 2009). Targets that are regulated at the RNA level can be identified by profiling mRNAs on microarrays. This technology is easily accessible but does not identify targets regulated only at protein level. It is also possible, although more difficult, to profile proteins following miRNA activity manipulation using large scale quantitative mass spectrometry coupled with stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cultured cells (SILAC) (Baek et al. 2008; Selbach et al. 2008). In these studies both mRNAs and proteins were profiled and although many genes were regulated at the RNA and protein levels, a substantial number of targets were only suppressed at the translational level.

We previously profiled mRNAs by Affymetrix microarray following manipulation of the activity of miR-140 in the pluripotent mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line and identified several genes regulated at the RNA and protein levels by miR-140 (Nicolas et al. 2008). Here we describe an approach aimed at revealing targets regulated solely at the protein level without proteomics data. We combined our existing microarray data with a computational search for common sequence motifs in the promoters of genes that are affected by microRNA misexpression. Using this approach we identified and validated the transcription factor Smad3 as a direct miR-140 target regulated only at the protein level. We also showed that miR-140 suppresses the TGFβ pathway through targeting Smad3. Interestingly, TGFβ treatment transiently suppresses miR-140 expression forming a double negative feedback loop. The approach described here could be used to reanalyze previously generated microarray data to identify miRNA targets regulated only at the protein level.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

An approach to analyze the promoter of indirect targets

miR-140 is specifically expressed in the cartilage of developing zebrafish (Wienholds et al. 2005) and mouse embryos (Tuddenham et al. 2006), and an important role for miRNAs in chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation was demonstrated by Kobayashi et al. (2008). We recently generated mRNA expression profiles of C3H10T1/2 cells following overexpression or suppression of miR-140 (Nicolas et al. 2008). This approach identified several direct miR-140 targets that showed higher or lower mRNA levels when the miRNA was silenced or overexpressed, respectively. To identify miRNA targets that are regulated only at the protein level we hypothesized that the mRNA level of a discrete subset of genes would be regulated by such targets. Many indirect miRNA targets were identified in our microarray experiments; these were mRNAs that showed differential expression, but did not contain potential miR-140 target sites. We assumed that the promoter sequences of some of these genes contain a common sequence motif recognized by a direct miRNA target that remained undetected by the microarray analysis because its mRNA level was not affected by the miRNA. To test whether we could find such motifs we first analyzed a transcription factor that is a known miRNA target. The Hand2 transcription factor is regulated by miR-1 at protein level (Zhao et al. 2005), and its core recognition sequence is CATCTG (Dai and Cserjesi 2002). In addition, mRNA expression profiles of HeLa cells in the presence or absence of miR-1 are available (Lim et al. 2005). First we compared the percentage of human genes that contain CATCTG in their promoter sequence to the percentage of CATCTG containing promoters of the genes that were down-regulated by miR-1. The two percentages were similar, suggesting that this method was not sensitive enough, although there was a slight enrichment for the CATCTG hexamer in the set of genes that were suppressed by miR-1 (54% compared with 46%). Hand2 is probably only one of several miR-1 direct targets that positively regulates the expression of other genes (indirect miR-1 targets), which would explain why the enrichment is not strong. However, we noticed that the CATCTG motif was very strongly underrepresented in the promoters of genes that were up-regulated by miR-1 (25% compared to 46%). In fact, the Hand2 recognition motif was the most underrepresented hexamer motif in the promoters of miR-1 induced genes out of all possible 4096 hexamer sequences. The most likely explanation of this is that most of the Hand2 targets are positively regulated by the transcription factor, and many of the genes containing a Hand2 recognition site are not induced by miR-1 because of the reduced level of Hand2.

Identification and validation of Smad3 as a miR-140 target

Next, we searched among the most underrepresented hexamers in the promoters of genes induced by miR-140 in our experiments and identified the CAGACT motif as the only one that also showed a slight increase in the promoters of genes down-regulated by miR-140 (up to 51% from 47%). A subsequence of this motif—CAGAC—is the recognition site of the Smad family of transcription factors that are involved in the TGFβ signaling pathway (Dennler et al. 1998). We then tested whether any of the Smad genes contain a potential miR-140 target site and found that the 3′ UTR of Smad3 contains three sites that show perfect match to the seed sequence of miR-140 (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Smad3 is regulated at the protein level but not at the RNA level by miR-140. (A) Top panel: Northern blot analysis of Smad3 expression following transfection of cells with LNA-antimiR-449, LNA-antimiR-140, siRNA-96, or siRNA-140. Three independent experiments are shown to demonstrate reproducibility. Membranes were first hybridized with the Smad3-specific probe then following stripping they were rehybridized with a Gapdh-specific probe to show equal loading. Bottom panel: Signal intensities were quantified with a phosphorimager. Smad3 signals were first normalized to the corresponding Gapdh signal then to the corresponding mock sample. There was no statistically significant difference between the samples (student t-test). (B) Top panel: Western blot analysis of Smad3 accumulation in cells transfected with LNA-antimiR-449, LNA-antimiR-140, siRNA-96, or siRNA-140. Equal loading is shown with an Actin probe. Bottom panel: Signal intensities were quantified with Quantity One software (version 4.5.1; Bio-Rad). Smad3 signals were first normalized to the corresponding Actin signal then to the corresponding mock sample. The LNA-antimir-140 treatment gave significantly higher signal than the LNA-antimir-449 or mock (P < 0.05) and the siRNA-140 samples had significantly lower intensity than the siRNA-96 or mock (P < 0.01; both Students t-test).

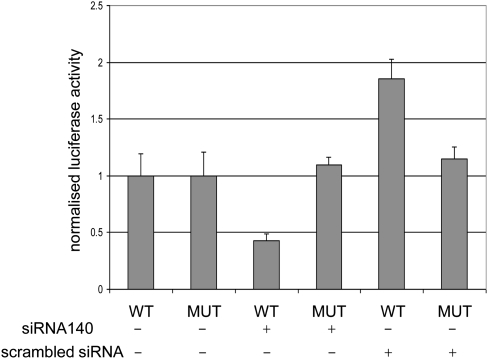

Validation of Smad3 as a direct miR-140 target involved two approaches. First we showed by Northern blot analysis that the mRNA level of Smad3 remained unchanged after manipulation of miR-140 activity (Fig. 1A). However, Western blotting revealed that the protein level of Smad3 was reduced after transfection of miR-140 mimicking siRNA into C3H10T1/2 cells and was increased after suppressing endogenous miR-140 activity by antimiR-140 (Fig. 1B). These data confirmed that miR-140 directly or indirectly regulated Smad3 at the protein level without affecting mRNA accumulation. Next, we tested whether Smad3 was a direct or indirect target of miR-140. The 3′ UTR of Smad3 was cloned downstream of the luciferase gene and luciferase activity was measured in the presence or absence of miR-140 mimicking siRNA. Luciferase activity was significantly lower following the siRNA transfection suggesting that Smad3 is a direct target of miR-140 (Fig. 2). Mutations were introduced to all three potential target sites, which rendered the construct insensitive to the siRNA (Fig. 2), confirming Smad3 as a direct target. It is not clear why the scrambled siRNA increased luciferase activity from the wild-type, but not from the mutant, construct. The sequence of the scrambled siRNA is not specified by the manufacturer; therefore, it is difficult to test whether it targets a factor that is involved in any way in the regulation of the Smad3 3′ UTR.

FIGURE 2.

Smad3 is a direct target of miR-140. Luciferase assays were carried out to address whether Smad3 is directly targeted by miR-140. The wild-type 3′ UTR sequence of Smad3 was cloned downstream of the luciferase gene and this plasmid (WT) was transfected with or without siRNAs mimicking miR-140 or scrambled siRNA. A mutant (MUT) construct was also used that contained mutations in all three predicted target sites of miR-140. Luciferase activities were normalized to transfections without siRNAs. The difference in luciferase activity between wild type and mutant constructs, in the presence of siRNA-140, was statistically significant (P < 0.001 by Students t-test).

Several target genes of miR-140 have been identified recently including histone deacetylase 4 (Tuddenham et al. 2006), platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (Eberhart et al. 2008), CXC group of chemokine ligand 12 (Nicolas et al. 2008), and Smad3 is another biologically relevant target gene. The Smad transcription factor family is part of the TGFβ pathway (Heldin et al. 1997), which plays a role in many diverse biological processes including chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation (Yang et al. 2001). Other Smad proteins were also shown to be regulated by miRNAs during osteogenic differentiation. Smad5 is targeted by miR-135, which itself is down-regulated by bone morphogenic protein 2 (Li et al. 2008), and Smad1 is targeted by miR-26 during late osteoblast differentiation (Luzi et al. 2008).

Interaction between the TGFβ pathway and miR-140

Since Smad3 is part of the TGFβ signaling pathway we hypothesized that miR-140 suppresses the TGFβ-dependent transcriptional responses. This was tested by measuring the transcriptional activity of a TGFβ/Smad-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid known as CAGA12, which contains 12 tandem copies of a Smad/DNA binding element CAGAC sequence in the presence and absence of TGFβ and miR-140 (Fig. 3A). We found that TGFβ strongly induced luciferase activity in the absence of miR-140. However, miR-140 dramatically suppressed the induction of luciferase activity by TGFβ confirming that miR-140 indeed regulates the TGFβ-dependent Smad transcriptional response. We also tested a few endogenous targets of the TGFβ pathway by measuring the accumulation of PAI1, TIMP3, and ADAM12 mRNAs by qRT-PCR after induction by TGFβ in the presence or absence of miR-140 (Fig. 3B–D). The results confirmed that induction of endogenous TGFβ targets was also suppressed by miR-140. We also tested whether the accumulation of miR-140 is dependent on TGFβ by measuring the level of miR-140 following TGFβ induction (Fig. 4A). Accumulation of the miRNA showed a gradual decrease during the first 24 h after TGFβ induction, but then its level was increased toward the basal level by 48 h. This effect was specific to miR-140 because miR-21 did not show the same pattern (Fig. 4A). The time course experiment was also repeated in the absence of TGFβ induction, where the miR-140 level did not change throughout the time course. These results established a double negative feedback loop for the TGFβ pathway and miR-140, and could provide a gene regulatory network in which the microRNA responsible for down-regulating Smad3 is itself a transcriptional target for the TGFβ pathway. This could generate a pulsed signal and provide a biologically significant mechanism that controls time-dependent signaling strength and Smad threshold following activation of the TGFβ pathway within an appropriate cellular context.

FIGURE 3.

TGFβ response is suppressed by miR-140. (A) Luciferase assays were carried out to measure the effect of miR-140 on a CAGAC promoter driven Luciferase gene. TGFβ induced a strong response in the presence of a scrambled siRNA (SCR), but the TGFβ mediated induction was suppressed in the presence of miR-140. The difference in luciferase activity between scrambled and miR140-specific siRNA, in the presence of TGFβ was statistically significant (P < 0.001 by Students t-test). (B–D) 10T1/2 cells were transfected with siRNAs mimicking miR-140 or scrambled siRNA. RNA was extracted and cDNA prepared following TGFβ treatment (4 ng/mL). PAI-1 (B), TIMP3 (C), and ADAM12 (D) expression was analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR and expression was normalized to 18S expression. The difference in expression level between scrambled and miR140-specific siRNA, in the presence of TGFβ was statistically significant for all three genes (P < 0.05 by Students t-test).

FIGURE 4.

Accumulation of miR-140 is transiently suppressed by TGFβ. (A) Time course Northern blot analysis of miR-140 following TGFβ treatment of 10T1/2 cells. TGFβ was applied once (5 ng/mL) and total RNA was extracted 1, 3, 6, 16, 24, and 48 h after the treatment. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a miR-21 probe to show that the effect is specific for miR-140 or with a U6 probe to demonstrate equal loading. Three independent results are shown for miR-140 accumulation. (B) Accumulation level of miR-140 in 10T1/2 cells is shown without applying TGFβ treatment to demonstrate that the decrease in miR0140 level is due to TGFβ.

The TGFβ pathway interacts with several other miRNAs. It was reported that miR-21 is post-transcriptionally induced by TGFβ in vascular smooth cells through interaction of Smad proteins and Drosha, which leads to increased activity of Drosha and increased processing of the primary miR-21 transcript (Davis et al. 2008). miR-24 was shown to be repressed by TGFβ and it was also demonstrated that this repression was Smad3-dependent during skeletal muscle differentiation (Sun et al. 2008). mir-155 is required for TGFβ induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is up-regulated by TGFβ (Kong et al. 2008). Two miRNA clusters (miR-106b-25 and miR-17-92) were also shown to modulate the TGFβ signaling in different tumors (Petrocca et al. 2008).

This study identified Smad3 as a direct target of miR-140 and demonstrated that miR-140 suppresses the TGFβ pathway, most likely through targeting Smad3. We used only mRNA array data to identify Smad3, although it is only regulated at protein level. The approach we described can be used to reanalyze existing mRNA data sets following miRNA manipulation and on data sets generated in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nucleotide sequence and microarray data analysis

The promoter region of a gene was defined as the 2000 nt upstream of the gene's transcription start site. Nucleotide sequences were extracted from Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org). MiR-1 overexpression microarray data were downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, accession number GSE2075). Differentially expressed genes were obtained as described previously (Lim et al. 2005). miR-140 overexpression and suppression microarray data are also available on GEO (accession number GSE13590). Differentially expressed genes were obtained as described previously (Nicolas et al. 2008).

Western and Northern blot

10T1/2 cells (3 × 104 cells/well) were transfected with siRNA-140 or siRNA-96 (30nM) (Dharmacon) and antimir-140 or antimir-449 (10nM) (Santaris) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The transfections were repeated 48 h after the first transfections. SiRNA-96 consisted of 5′-UUUGGCACUAGCACAUUUUUGCUUG-3′ and 5′-AGCAAUCAUGUGUAGUGCCAAUAU-3′ oligonucleotides. Whole cell lysates were extracted 48 h after the second transfection and Western blotting was performed using standard procedures. SMAD3 and B-actin antibodies from rabbit and horseradish-peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit antibody were purchased from Abcam.

Total RNA was extracted from 10T1/2 cells using TRIzol reagent, following the recommendations of the supplier (Invitrogen). To detect Smad3 mRNA, 20 μg of total RNA from each sample were separated on 1% denaturing agarose gel, blotted to membrane and hybridized to radioactively labeled probes overnight at 37°C in ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (Ambion). Probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using Ready-to-Go DNA labeling beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), following the instructions of the supplier. The Smad3 probe was the same 2935-bp fragment used in the luciferase assays. The loading control Gapdh probe is a 298-bp fragment PCR amplified using the oligonucleotide pair 5′-ATTTGGCCGTATTGGGCGCCTGGTCACCA-3′ and 5′-AAGACACCAGTAGACTCCACGACATAC-3′.

To detect miR140 expression, 30 μg of each total RNA sample were resolved on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a Zeta-probe membrane (Bio-Rad) using a semidry electroblotting apparatus. Membranes were hybridized overnight at 37°C in ULTRAhyb-Oligo hybridization buffer (Ambion) with γ-ATP labeled oligonucleotides complementary to miR140. Membranes were exposed to Kodak Phosphor Screen SD230 for quantification. After exposition, the screen was scanned on a Molecular Imager FX reader (Bio-Rad).

DNA constructs

A modified pGL3 control vector (Tuddenham et al. 2006) was used for cloning the Smad3 3′ UTR. For the wild-type construct, 2935 bp of the Smad3 3′ UTR was PCR amplified from mouse genomic DNA using a pair of oligonucleotides (5′-AGACACTAGGAGTAAAGGGAGCGGGTTG-3′ and 5′-GCTTTAAGGAATTGTTACATAAATACGAAAGCGGCAGA-3′) and cloned into pGemT-Easy (Promega). The 3′ UTR was then PCR amplified from pGemT-Easy to incorporate SacI and NheI restriction sites to the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and inserted into the modified pGL3. For the mutant pGL3 construct, the seed sequence of the three predicted target sites were replaced with eight point mutations.

Luciferase reporter assays

3T3 cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) containing 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Invitrogen). Cells (3 × 104cells/well) were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with either wild-type or mutant constructs (200 ng), with and without siRNA-140 (Dharmacon) or negative control siRNA (Quiagen) (30 nM). SiRNA-140 consisted of 5′-CAGUGGUUUUACCCUAUGGUAG-3′ and 5′-ACCAUAGGGUAAAACCACUGAG-3′ oligonucleotides. As a positive control, the modified pGL3 control vector was used without a 3′ UTR insert. Lipofectamine only treated cells served as negative controls. Transfections were carried out six times in triplicate using two independent plasmid preparations. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h later using a multilabel counter (Victor2, Perkin–Elmer). Relative reporter activity for siRNA-140 treated cells was obtained by normalization to non-siRNA-140 treated wild-type or mutant constructs, respectively.

C3HT101/2 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 104cells/well for 24 h and transfected (n = 2) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using the following DNA mixes: 250 ng (CAGAC)12/pGL3-luciferase plasmid, 50 ng pRSV-Bgalactosidase plasmid, 100 mM mir-140 siRNA (or scrambled) for 48 h. Cells were stimulated with 5 ng human TGF-beta for 6/16 h prior to cell lysates being prepared and assayed for relative luciferase activity (Promega). The luciferase data were standardized for B-galactosidase activity (Beta-Glo Luciferase Assay system, Promega).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamers in a total volume of 20 μL according to the manufacturer instructions. cDNA was stored at −20°C.

PAI-1 primers and probes were designed using the Roche Universal probe library. The 18S ribosomal RNA gene was used as an endogenous control to normalize for RNA loading (18S rRNA primers and probes were purchased from Applied Bioscience).

Relative quantification of genes was performed using the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. PCR reactions contained 5 ng of reverse transcribed RNA (1 ng for 18S), 50% Taqman 2X Master mix (Applied Biosystems), 100 nM of each primer and 200 nM probe in a total volume of 25 μL. Conditions for the PCR reaction were 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the European Commission (FP6 Integrated Project SIROCCO LSHG-CT-2006-037900) to T.D. H.P. is a student of Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência's Ph.D. Program in Computational Biology (sponsored by Fundação Para a Ciência e a Tecnologia [FCT], Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Siemens SA Portugal) and was supported by FCT fellowship SFRH/BD/33204/2007.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1701210.

REFERENCES

- Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Doerks T, Stark A, Bork P, Izaurralde E. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:1885–1898. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA–target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y-S, Cserjesi P. The basic helix–loop–helix factor, HAND2, functions as a transcriptional activator by binding to e-boxes as a heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12604–12612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Lagna G, Hata A. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature. 2008;454:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature07086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF β-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. 1998;17:3091–3100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart JK, He X, Swartz ME, Yan YL, Song H, Boling TC, Kunerth AK, Walker MB, Kimmel CB, Postlethwait JH. MicroRNA Mirn140 modulates Pdgf signaling during palatogenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:290–298. doi: 10.1038/ng.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Rehwinkel J, Stricker M, Huntzinger E, Yang SF, Doerks T, Dorner S, Bork P, Boutros M, Izaurralde E. Target-specific requirements for enhancers of decapping in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:2558–2570. doi: 10.1101/gad.443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Nishihara T, Rehwinkel J, Fauser M, Izaurralde E. Deadenylation is a widespread effect of miRNA regulation. RNA. 2009;15:21–32. doi: 10.1261/rna.1399509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006;312:75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-β signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Lu J, Cobb BS, Rodda SJ, McMahon AP, Schipani E, Merkenschlager M, Kronenberg HM. Dicer-dependent pathways regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:1949–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W, Yang H, He L, Zhao JJ, Coppola D, Dalton WS, Cheng JQ. MicroRNA-155 is regulated by the transforming growth factor β/Smad pathway and contributes to epithelial cell plasticity by targeting RhoA. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6773–6784. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00941-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Hassan MQ, Volinia S, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Croce CM, Lian JB, Stein GS. A microRNA signature for a BMP2-induced osteoblast lineage commitment program. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:13906–13911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804438105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;443:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzi E, Marini F, Sala SC, Tognarini I, Galli G, Brandi ML. Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:287–295. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas FE, Pais H, Schwach F, Lindow M, Kauppinen S, Moulton V, Dalmay T. Experimental identification of microRNA-140 targets by silencing and overexpressing miR-140. RNA. 2008;14:2513–2520. doi: 10.1261/rna.1221108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocca F, Vecchione A, Croce CM. Emerging role of miR-106b-25/miR-17-92 clusters in the control of transforming growth factor β signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8191–8194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehwinkel J, Behm-Ansmant I, Gatfield D, Izaurralde E. A crucial role for GW182 and the DCP1:DCP2 decapping complex in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. RNA. 2005;11:1640–1647. doi: 10.1261/rna.2191905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethupathy P, Megraw M, Hatzigeorgiou AG. A guide through present computational approaches for the identification of mammalian microRNA targets. Nat Methods. 2006;3:881–886. doi: 10.1038/nmeth954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Zhang Y, Yang G, Chen X, Zhang Y, Cao G, Wang J, Sun Y, Zhang P, Fan M, et al. Transforming growth factor-β-regulated miR-24 promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2690–2699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuddenham L, Wheeler G, Ntounia-Fousara S, Waters J, Hajihosseini MK, Clark I, Dalmay T. The cartilage specific microRNA-140 targets histone deacetylase 4 in mouse cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4214–4217. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Berezikov E, de Bruijn E, Horvitz HR, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science. 2005;309:310–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Fan J, Belasco JG. MicroRNAs direct rapid deadenylation of mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:4034–4039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510928103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Chen L, Xu X, Li C, Huang C, Deng CX. TGF-β/Smad3 signals repress chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation and are required for maintaining articular cartilage. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:35–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]