Abstract

Retroviruses package their genome as RNA dimers linked together primarily by base-pairing between palindromic stem–loop (psl) sequences at the 5′ end of genomic RNA. Retroviral RNA dimers usually melt in the range of 55°C–70°C. However, RNA dimers from virions of the feline endogenous gammaretrovirus RD114 were reported to melt only at 87°C. We here report that the high thermal stability of RD114 RNA dimers generated from in vitro synthesized RNA is an effect of multiple dimerization sites located in the 5′ region from the R region to sequences downstream from the splice donor (SD) site. By antisense oligonucleotide probing we were able to map at least five dimerization sites. Computational prediction revealed a possibility to form stems with autocomplementary loops for all of the mapped dimerization sites. Three of them were located upstream of the SD site. Mutant analysis supported a role of all five loop sequences in the formation and thermal stability of RNA dimers. Four of the five psls were also predicted in the RNA of two baboon endogenous retroviruses proposed to be ancestors of RD114. RNA fragments of the 5′ R region or prolonged further downstream could be efficiently dimerized in vitro. However, this was not the case for the 3′ R region linked to upstream U3 sequences, suggesting a specific mechanism of negative regulation of dimerization at the 3′ end of the genome, possibly explained by a long double-stranded RNA region at the U3-R border. Altogether, these data point to determinants of the high thermostability of the dimer linkage structure of the RD114 genome and reveal differences from other retroviruses.

Keywords: gammaretrovirus, RNA dimerization, mRNA, RD114, palindromic stem–loops

INTRODUCTION

Retroviruses package their genome as dimers of two identical RNA molecules (Greatorex 2004; Paillart et al. 1996, 2004). The dimeric nature of retroviral genomes allows for template switching during reverse transcription, which contributes to replication fidelity and virus recombination (Hu and Temin 1990; King et al. 2008). A dimer linkage structure (DLS) involved in the association of the two strands was first mapped to the 5′ part of retroviral genomic RNAs by electron microscopic analysis of RNA dimers from virions (Bender and Davidson 1976; Kung et al. 1976). Later studies of RNAs of several retroviruses have identified base-pairing between palindromic stem–loop (psl) sequences of the DLS as a major common mechanism of intermolecular interaction in vitro (Paillart et al. 2004; Greatorex 2004). In support of a critical role of these motifs in virus replication, mutations that impair RNA-dimerization in vitro have in many instances been found to reduce or prevent viral replication (Aagaard et al. 2004; Paillart et al. 2004). However, the DLS overlaps with cis-elements for intracellular trafficking and encapsidation of retroviral RNA, which complicates the distinction between specific effects of a given mutation on RNA-dimerization and RNA transport and packaging (Basyuk et al. 2005; Smagulova et al. 2005). A favored hypothesis holds that the processes are, in fact, linked with RNA dimerization being a prerequisite for encapsidation of the genome into particles (Hibbert et al. 2004; Paillart et al. 2004).

The feline endogenous virus RD114 (Okabe et al. 1973) and a related baboon endogenous virus (BaEV) were reported to have unique features since RNA dimers isolated from virions were found to have a higher stability and melt only at 87°C (Kung et al. 1975), while melting temperatures of retroviral RNA dimers formed in vitro or isolated from mature viral particles are usually in the range of 55°C–70°C (Bender et al. 1978; Darlix et al. 1990; Fu and Rein 1993; Fu et al. 1994; Ortiz-Conde and Hughes 1999). RD114 was derived from a cross-species transmission of a BaEV-related virus from primates to a cat ancestor. Phylogenetic analysis of Felis cattus endogenous virus (FcEV) as well as RD-114 fragments amplified from cat species, and comparison with BaEV-related fragments from primate DNA, suggested that RD-114 is actually a new recombinant between FcEV type C genes and the env gene of BaEV (van der Kuyl et al. 1999).

We have investigated the unusual melting properties of RD114 RNA dimers and report here that dimers generated from in vitro synthesized fragments of RD114 RNA have a high thermal stability with involvement of multiple dimerization sites located in the 5′ region from positions 1 to 472 downstream from the splice donor (SD) site. Although the leader region of RD114 RNA contains several features reminiscent of prototypic gammaretroviruses such as MLVs (Paillart et al. 2004), our results point to a uniquely stable dimer linkage structure of the RD114 genome resulting from the involvement of additional psl motifs. We find that four of these dimerization motifs are conserved in two baboon endogenous retroviruses related to RD114.

RESULTS

In vitro dimerization of RD114 RNA fragments

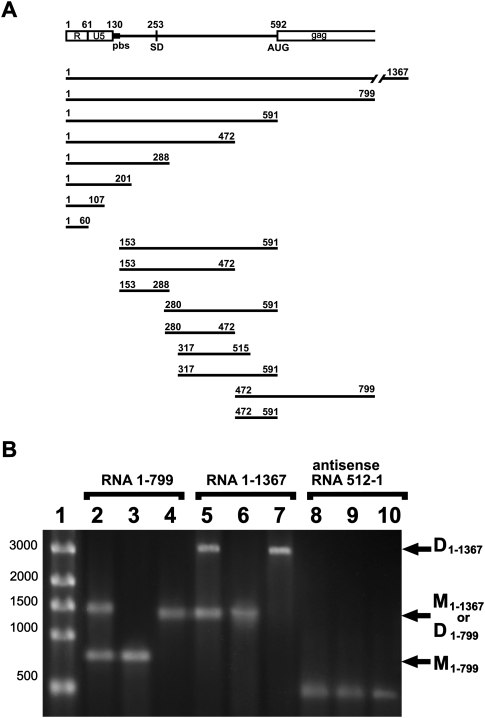

The 5′part of RD114 genomic RNA is depicted in Figure 1A. The functional annotation is based upon published work and database information with the exception of the SD, which was mapped in this work by cDNA sequence analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The intron of env mRNA was found to span from nt 253 to nt 5574. RNA samples for dimerization studies were generated in vitro by T7 polymerase using fragments of the infectious molecular clone SC3C as a template. Figure 1A provides the location of 17 in vitro transcribed RNA fragments. A representative analysis of RNA monomers and dimers by agarose gel electrophoresis is shown in Figures 1B and 2B. For all three probes (1–1367, 1–799, and 1–591), the RNA product of the transcription reaction contains a mixture of monomers and dimers (Fig. 1B, lanes 2,5; Fig. 2B, lane 1). Such cotranscriptional dimerization has previously been observed for RNA of HIV-1 (Sinck et al. 2007) and Mo-MLV (Flynn and Telesnitsky 2005). After denaturation and renaturation in dimerization buffer at 50°C, the samples contained a prominent dimer band and no or very little monomeric band (Fig. 1B, lanes 4,7; Fig. 2B, lane 5). After dimerization, the samples were in some cases observed to contain an increase in discrete bands of slower mobility corresponding to higher order oligomers (Fig. 2A). No dimerization was observed using an antisense RNA fragment spanning from position +512 to +1 (Fig. 1B, lanes 8–10).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Scheme of the first 799 nt of RD114 genomic RNA and representation of the different RNA fragments synthesized for dimerization analysis. (R) Repeat sequence; (U5) unique sequence at the 5′ end of the RNA genome; (pbs) primer-binding site; (SD) splice-donor site, mapped in this study, and (AUG) translation initiator codon of gag. (B) Representative 1% agarose gel electrophoresis of RD114 RNA fragments. (Lane 1) ssRNA ladder; (lanes 2–4) RD114 1–799 nt RNA fragment; (lanes 5–7) RD114 1–1367 nt RNA fragment; (lanes 8–10) RD114 antisense 512-1 nt RNA fragment. (Lanes 2,5,8) RNA was loaded on the gel just after in vitro transcription. (Lanes 3,6,9) RNA after in vitro transcription was cleaned on affinity columns and melted at 90°C for 2 min in water. (Lanes 4,7,10) RNA after melting was dimerized at 50°C for 30 min in the presence of dimerization buffer (see Materials and Methods). D, dimers; M monomers.

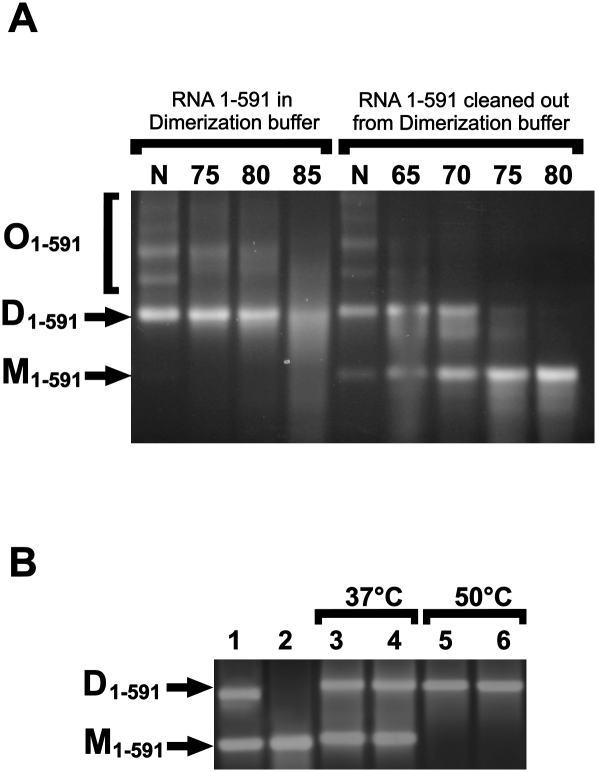

FIGURE 2.

Formation of dimers and oligomers of 1–599 RD114 RNA determination of their thermal stability. One percent agarose gel electrophoresis of 1–599 RD114 RNA fragment. (A) RNA was cleaned out from in vitro transcription mix, denatured, and incubated with dimerization buffer as described. After dimerization 10 times diluted aliquots of RNA was incubated for 10 min at indicated temperatures or was cleaned out from dimerization buffer before heating in water. (B) RNA was cleaned out from in vitro transcription mix (lane 1), denatured (lane 2), and then incubated with dimerization buffer (lanes 3,5) or transcription buffer (lanes 4,6). RNA probes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C (lanes 3,4) or 20 min at 50°C (lanes 5 and 6). N, no heating; D, dimers; M monomers; O, oligomers.

The observation of cotranscriptional dimerization of retroviral RNA in vitro might reflect the in vivo situation when cotranscriptional folding and/or increased local concentration of RNA can promote dimerization. Alternatively, the specific conditions of in vitro transcription such as salt concentrations, long incubation time, and a high concentration of RNA might induce dimerization. To test this possibility, 1–591 RNA was, after melting, dissolved in buffer for in vitro transcription and incubated for 1 h at 37°C or for 20 min at 50°C. As a control, aliquots of RNA were dissolved with dimerization buffer and incubated at the same conditions. As shown in Figure 2B, there was no difference in the efficiencies of dimerization in transcriptional and dimerization buffers. Dimerization at 50°C was much more efficient than at 37°C for both dimerization and transcription buffer. No dimerization was observed after incubation of the samples with water (data not shown). Thus, in spite of the fact that the efficiency of cotranscriptional dimerization was slightly higher than during incubation in transcription buffer at 37°C (Fig. 2B, lanes 1,4), transcription buffer alone was capable of inducing dimerization of RD114 RNA.

Thermal stability of RNA dimers

To analyze the thermal stability of RNA dimers, we first focused on the 1–591 RNA fragment. After dimerization the samples were diluted and heated for 10 min at the indicated temperatures (Fig. 2, left part of the gel). We note that the there was no possibility to determine a melting temperature for D1–591 structures under these conditions due to a significant amount of dimer present even after heating at 85°C. The explanation could be reannealing of dimers in the diluted dimerization buffer. The samples were purified on columns to remove the dimerization buffer prior to heating (Fig. 2, right part of the gel). Under these conditions of heating in water equal amounts of dimers and monomers were present after heating at around 70°C. Similar results were obtained using probes 1–1367 and 1–799 (data not shown). Cotranscriptionally formed dimers exhibited the same thermal stability as those formed after denaturation and renaturation. Oligomers also showed different behavior during heating in dimerization buffer and in water. When heated in dimerization buffer oligomers were converted to dimers, whereas they were converted to monomers when heated in water (Fig. 2A, cf. right and left parts), arguing that oligomers are held together by weaker interactions in addition to the stronger interactions forming the dimers.

To verify that the high melting temperatures of RD114 RNA dimers were not caused by special features of our experimental conditions, we included a parallel analysis of an RNA fragment derived from position 1–638 of the gammaretrovirus Akv–MLV. When heated in diluted dimerization buffer, dimers of this RNA were mostly dimeric at 65°C and about 50% monomeric at 75°C. After removal of dimerization buffer Akv dimers were only 10%–20% dimeric after heating at 50°C (Table 1). This is in accordance with reports that Akv virion RNA dimers had a Tm2<260°C in 0.1 M Na+ (Bender et al. 1978). In our subsequent investigations the thermal stability of dimers of RD114 RNA was analyzed after removal of the dimerization buffer.

TABLE 1.

Dimerization of different fragments of RD114 genomic RNA

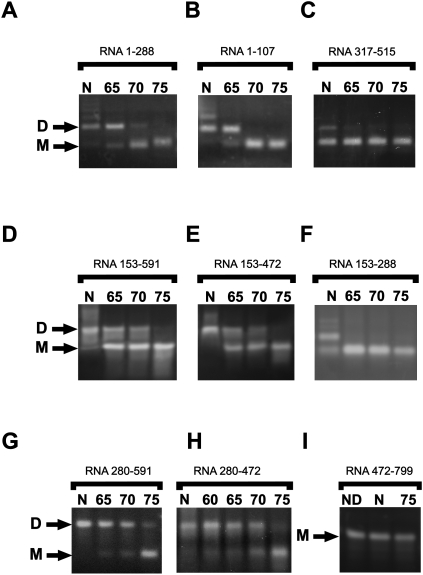

To identify RNA regions contributing to the formation of stable homodimers, we applied a variety of shorter RNA fragments of the 5′ part of RD114 RNA as shown in Figure 1. A summary of the results is given in Table 1. Representative results of these mapping efforts are shown in Figure 3. We first note that dimer formation was observed for all fragments shown in Figure 3 except for the long downstream fragment 472–799 RNA (Fig. 3I). We next note that some but not all fragments analyzed allow the formation of dimers that are stable at 65°C or above. Interestingly, more than one region across the 1–472 window allows the formation of such stable dimers. This is shown by data from nonoverlapping RNA fragments, 1–288 and 1–107 versus 280–472 in Figure 3, A, B, and H, respectively, as well as 1–107 versus 153–591 and 153–472 in Figure 3, B, D, and E, respectively. The highest thermostability was observed for dimers of 288–591 and 280–472 RNA (Fig. 3G). The results of dimerization using different fragments are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 3.

Dimerization and determination of thermal stability of dimers of RD114 genomic RNA fragments. RNA was cleaned from in vitro transcription mix, denatured, and incubated with dimerization buffer as described. After dimerization, RNA was cleaned from dimerization buffer using affinity columns and aliquots incubated for 10 min in water at the indicated temperatures. (A) 1–288 RNA fragment; (B) 1–107 RNA fragment; (C) 317–515 RNA fragment; (D) 153–591 RNA fragment; (E) 153–472 RNA fragment; (F) 153–288 RNA fragment; (G) 280–591 RNA fragment; (H) 280–472 RNA fragment; (I) 472–799 RNA fragment. N, no heating; D, dimers; M monomers; ND, this probe was not incubated with dimerization buffer.

Mapping dimer linkage sites by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides

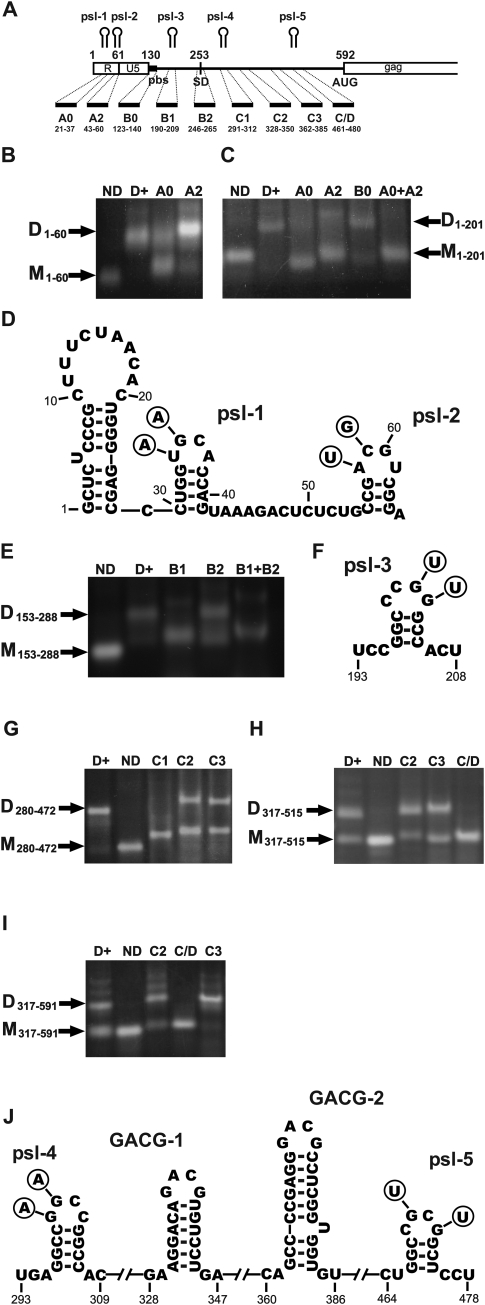

The RNA folding program Mfold (Zuker 2003) was used to predict psl structures in the 5′ part of RD114 RNA with a possible role in RNA dimerization. Figure 4A shows the location of candidate motifs psl-1–5 in RD114 RNA. Nine antisense oligodeoxynucleotides distributed across the 5′ untranslated region (Fig. 4, Table 2) were used to probe the role of individual regions in dimer formation by the addition of 10-fold molar oligonucleotide excess to the dimerization reaction. Three predicted stem–loop structures of the R region are shown in Figure 4D, including two short stems with palindromic-loop sequences, psl-1 and psl-2. As shown in Figure 4B, dimer formation of 1–60 RNA including psl-1 and terminating in the loop of psl-2 was partially inhibited by addition of antisense-oligonucleotide A0 complementary to positions 21–37 and thereby disrupting the psl-1. It should be noted that the annealed oligonucleotide affected the mobility of the short RNA probe such that the lower band in the reaction with A0 moved slightly slower than the monomeric form, whereas the mobility of the upper band corresponded to the dimer. This is in agreement with annealing of A0 to the RNA monomer but not to the RNA dimer. In contrast, oligonucleotide A2 with complementarity to positions 43–69 had very little inhibitory effect on the dimerization of 1–60 RNA. In this case, the mobility as well as the monomeric form as the dimeric form were slightly reduced. These data are supportive for a role of psl-1 in dimerization.

FIGURE 4.

Antisense oligonucleotide mapping of dimerization sites on the RD114 leader RNA fragments. After synthesis and cleaning, RNA was denaturized at 90°C for 2 min and then incubated at 50°C for 30 min with dimerization buffer in the presence or absence of antisense DNA oligonucleotides as indicated. Probes were used for electrophoresis as described above. (A) Scheme of the first 799 nt of RD114 genomic RNA and representation of the antisense DNA oligonucleotides used in this study. Localization of the mapped palindromic stem–loops (psl) involved in dimerization indicated. (B) Antisense inhibition of dimerization of 1–60 RNA fragment (R-region); (C) antisense inhibition of dimerization of 1–201 RNA fragment; (D) predicted secondary structure of 1–65 nt RD114 genomic RNA, containing psl-1 and psl-2. The circles indicate nucleotide shifts in the created mutants; (E) antisense inhibition of dimerization of 153–288 RNA fragment; (F) predicted secondary structure of psl-3 (196–205 nt); (G) antisense inhibition of dimerization of 280–472 RNA fragment; (H) antisense inhibition of dimerization of 317–515 RNA fragment; (I) antisense inhibition of dimerization of 317–591 RNA fragment; (J) predicted secondary structure of psl-4 (296–207 nt), psl-5 (466–478 nt), and two stem–loops with GACG-loop motif (330–345 and 363–384). ND, this fragment was not incubated with dimerization buffer; D+ dimerized RNA with no antisense oligonucleotides; D, dimers; M, monomers.

TABLE 2.

DNA oligonucleotides used in antisense probing experiments

Experiments using the longer 1–201 RNA fragment terminating in the loop of psl-3 supported a role of psl-1 as well as psl-2 in dimerization. Oligonucleotides A0 and A2 had inhibitory effects, while oligonucleotide B0 matching another part of the RNA fragment had no major effect. Similarly, Figure 4, E and F, demonstrate a role of psl-3 in dimerization. The additional experiments shown in Figure 4 tested the role of psl-4 and psl-5 in dimerization. Strong inhibition of dimerization of 280–472 RNA by the C1 oligonucleotides is in support of a key role of psl-4; however, partial inhibition by neighboring antisense probes C2 and C3 may suggest additional interactions (Fig. 4G). Inhibition of 317–515 as well 317–591 RNA dimerization by oligonucleotide C/D but not by neighboring oligonucleotides C2 and C3 argue in favor of a role of psl-5 (Fig. 4H,I). The results from probing of regions overlapping with 153–591 were more complex than those analyzing the more upstream parts of the RNA, probably reflecting additional interactions beyond the stem–loop structures. For example, antisense oligonucleotide B2, which does not overlap with a psl motif, caused a slight inhibition of dimerization (Fig. 4E). Moreover, oligonucleotides C2 and C3, which also do not overlap with a psl motif, had an influence on the dimerization of 280–472 RNA. Interestingly, dimerization of the longer probe 317–591 but not the shorter RNA 317–515 probe was enhanced by oligonucleotide C3, an effect also inhibited by C/D (data not shown). These results are indicative of a possible existence of alternative secondary structures in vitro involving the target sequence of C3. One of these structures may be more prone to dimerization. In support of this possibility of a dimerization inhibitory activity of a downstream sequence we found that 317–591 RNA dimerized cotranscriptionally with high efficiency (about 80%, data not shown), whereas no more than 40% (in some experiments no more than 30%) was dimerized under standard dimerization conditions (see also Fig. 4I). Addition of C3 to the dimerization reaction enhanced dimerization to around 90%, similar to the level of cotranscriptional dimerization. Interestingly, antisense oligonucleotides C2 and C3 are complementary to regions predicted to form stem–loop structures with a GACG-tetraloop, similar to structures shown to be involved in RNA dimerization and packaging of other gammaretroviruses (Fig. 4J).

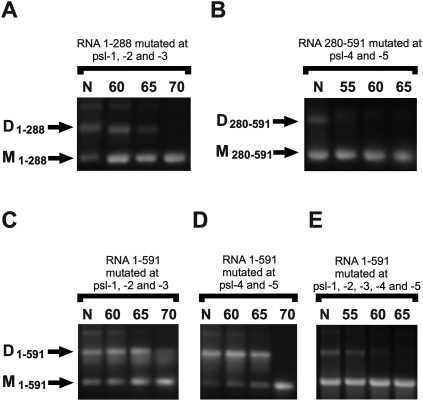

Mutations in the psls influence dimerization

To further address the role of putative psl sites in the dimerization of RD114 retroviral RNA we introduced mutations into these sequences. Mutations were designed to impair autocomplementarities of psl loops, besides to preserve secondary structures as predicted by Mfold. As shown in Figure 4D, the UGCA loop of psl-1 and ACGU loop of psl-2 were transformed to AACA and UGGU, respectively. Mutations in the psl-3 loop converted CCGG into CCUU (Fig. 4F). GGCC and CGCG loops of psl-4 and psl-5 were changed to AACC and CUCU, respectively (Fig. 4J). To test the influence of introduced mutations on the RD114 RNA dimerization we first split the leader region of the virus into two parts: from position 1 to 288 (containing first three psl sites upstream of splicing donor); and from position 280 to 591 (contains last two psl sites downstream from SD). Then we investigated the influence of solitary mutations or their combinations on the efficiency of dimerization of the corresponding RNA fragment as well as the thermal stability of dimers. We also investigated the effect of combinations of the loop mutations on the dimerization of full-length RD114 leader (positions 1–591). The results of the experiments using mutated RNAs are presented in Table 3. Representative gel electrophoresis pictures are shown in Figure 5.

TABLE 3.

Dimerization of fragments of RD114 genomic RNA with mutations in the psl sites

FIGURE 5.

Dimerization and determination of thermal dimer stability of RD114 genomic RNA fragments containing mutations in the psl sites. RNA was cleaned from in vitro transcription mix, denatured, and incubated with dimerization buffer as described. After dimerization, RNA was cleaned from dimerization buffer using affinity columns and aliquots incubated for 10 min in water at the indicated temperatures. (A) 1–288 RNA fragment with mutations in the psl-1, psl-2, and psl-3 sites; (B) 1–591 RNA fragment with mutations in the psl-4 and psl-5 sites; (C) 1–591 RNA fragment with mutations in the psl-1, psl-2, and psl-3 sites; (D) 1–591 RNA fragment with mutations in the psl-4 and psl-5 sites; (E) 1–591 RNA fragment with mutations in the psl-1, psl-2, psl-3, psl-4, and psl-5 sites. N, no heating; D, dimers; M, monomers.

All solitary mutations introduced had an influence on the stability of the corresponding RNA fragments. Thus, introduction of mutations disrupting complementarities in the psl-1, -2, or -3 did not abolish the dimerization of 1–288 RNA but decreased the melting temperatures of dimers by ∼7, 5, and 5 degrees, respectively (Table 3). Double-mutants with changed psl-1 and psl-2 had the same thermal stability as a solitary psl-1 mutant but had altered dimerization efficiency, and only 70% of the RNA turned into dimer under normal dimerization conditions (Table 3). The combination of psl-1, -2, and -3 mutations had a greater effect on dimerization and stability of 1–288 RNA dimers. Moreover, this mutant was dimerized as efficiently as 50% and the melting temperature of dimers dropped to 55°C in comparison with ∼67.5°C for wild-type RNA (Fig. 5A; Table 3).

In contrast to mutations in the 5′ part of the RD114 leader, solitary mutations in the psl-4 and psl-5 had an impact on both the efficiency of dimer formation and its stability. Mutation of psl-4 had much greater effects on the dimerization of 280–591 RNA than mutation in psl-5 (Table 3). About 60% of dimers were seen on the gel after induced dimerization of the psl-4 mutant in comparison with 90% of dimers for the psl-5 mutant. The psl-4/psl-5 double-mutant had a more drastic effect on dimerization, and only ∼30% of dimers were seen. Dimers of the psl-5 mutant were slightly less stable compared with wild-type RNA dimers (Table 3). However, dimers of both psl-4 and double psl-4 and psl-5 mutants completely disappeared after heating to only 55°C (Fig. 5B; Table 3).

To investigate the effect of mutations on the dimerization of full-length RD114 leader RNA we used the 1–591 fragment of viral RNA with the following combinations of mutated psl sites: (1) 5′ psl-mutated sites (psl-1, -2, and -3); (2) 3′ psl-mutated sites (psl-4 and -5); (3) all five psl-mutated sites. Both 5′ and 3′ mutation combinations had an influence on dimerization efficiency. Dimer formation of 1–591 RNA with changed 5′ psl sites was reduced to ∼60% (Fig. 5C). Mutation of 3′ psl sites only slightly affected the efficiency of dimerization and ∼90% of 1–591 RNA was seen as dimers on the gel (Fig. 5D). Tm for both 5′ and 3′ mutants was estimated to be about 67.5°C (Table 3); the dimerization of the 5′ mutant RNA was less efficient, but dimers of this mutant were slightly more stable. After heating at 70°C the presence of a small amount of 5′ mutant, but not 3′ mutant, dimers was seen on the gel (Fig. 5C,D). Mutation of all five putative psl sites had a drastic effect on dimerization. Only about 5% of dimers were seen after induced dimerization of full-mutated 1–591 RNA. These dimers were stable at 55°C but almost completely disappeared after heating at 60°C (Fig. 5E). Thus, all tested mutations had an influence on dimerization and thermal stability of RD114 RNA dimers. This experiment confirmed the role of psl sites in dimerization, and suggests cumulative effects of multiple dimerization sites on the high thermal stability of RD114 retroviral RNA.

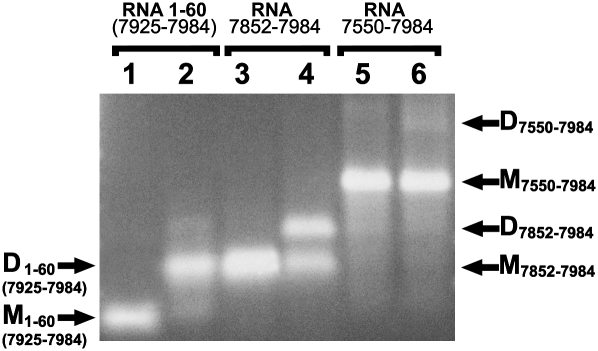

An influence of U3 sequences on dimerization of the downstream R region

The identification of RNA dimerization signals in the R region raised the question as to whether these would also function in their downstream context following U3. Interestingly, the Mfold program predicted an alternative structure of pls-1 in this context as shown in Figure 7B, below. Such a structure might disfavor intermolecular interaction of the palindromic sequences of pls-1. To test this, we compared dimer formation between the R fragment 1–60 RNA with the U3-R fragment 7852–7984 RNA containing 73 nucleotides of U3 in addition to the 60 nucleotides of R. The results of Figure 6, lanes 2 and 4, show that the extension of RNA 1–60 with U3 sequences in 7852–7984 RNA led to an inhibition of the dimer formation of about 50%. Further extension of the fragment into U3 sequences led to an additional reduction in dimer formation as shown in Figure 6, lane 6, where the fragment used was 7550–7984 RNA, including a possible interaction predicted for nucleotides 7846–7859 as shown in Figure 7B.

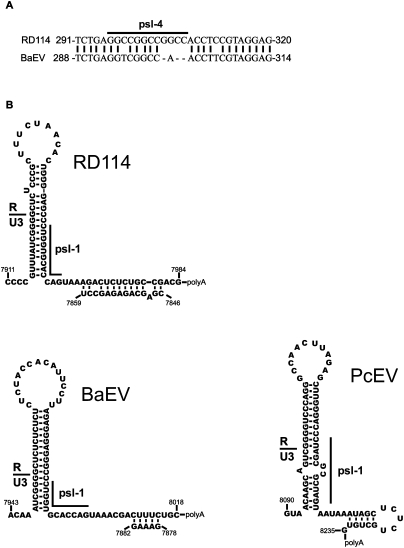

FIGURE 7.

(A) Short stretch of homology between RD114 and BaEV containing the psl-4 sequence. (B) Predicted secondary structures at 3′ ends of the genomes of the three studied viruses. Note: The PcEV sequence used for the 3′ end of genomic RNA was reconstructed using in part a sequence from 5′ LTR of the available virus clone (accession number AF142988) due to the presence of a deletion and point mutations at the 3′LTR (Mang et al. 1999).

FIGURE 6.

Influence of upstream sequences on the 3′ R RNA fragment dimerization. After synthesis and cleaning RNA was denaturized at 90°C for 2 min (lanes 1,3,5) and incubated at 50°C for 30 min with dimerization buffer (lanes 2,4,6). Probes were used for electrophoresis immediately after induced dimerization. (Lanes 1,2) RNA fragment corresponding R region of RD114 genome, bases from 1 to 60 or from 7925 to 7984; (lanes 3,4) RNA fragment corresponding to RD114 genome, bases from 7852 to 7984; (lanes 5,6) RNA fragment corresponding to RD114 genome, bases from 7550 to 7984. D, dimers; M, monomers.

Sequence and structural alignment

Due to a lack of data on the diversity of the RD114 virus it is not possible to perform a phylogenetic analysis of RD114 RNA dimerization motifs. However, two viruses, BaEV and PcEV (Papio cynocephalus endogenous retrovirus), with high homology with RD114 are known. It is suggested that BaEV is the ancestral virus for RD114 (van der Kuyl et al. 1999). Moreover, PcEV, a defective endogenous virus from the baboon genome, has been suggested to be the ancestor for BaEV (Mang et al. 1999). Interestingly, PcEV and RD114 are the only retroviruses using tRNAGly to initiate reverse transcription, unlike BaEV and other gammaretroviruses, which commonly use tRNAPro.

We performed sequence alignment and searched for conserved secondary structures in the leader genomes of RD114, BaEV, and PcEV viruses using SCARNA software (Tabei et al. 2006). The homology with the leader region of RD114 was on average only 65% for BaEV and 61.5% for PcEV. In spite of this, we found that psl motifs were highly conserved for all three viruses with the exception of the psl-2 site, which is unique to RD114 virus. Data of sequence and structural alignment of psl motifs are presented in Table 4. Other common conserved secondary structures found in the leader genomes of all viruses are the hairpin structure at the beginning of R and the two GACG-hairpin motifs (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Sequence and structural alignment of psl motifs from RD114, BaEV, and PcEV viruses

All common psl motifs are short (10–12 nt) G–C rich perfect palindromes. The locations of these motifs in the genomes are very similar for the three viruses. The level of sequence homology varies among different psl sites and viruses (Table 4). Interestingly, the least conserved psl motif is psl-4. In the genome of BaEV the psl-4 site was even disrupted by deletion of three nucleotides in the hairpin stem. We were able to find it only due to the presence of a short island of high homology between RD114 and BaEV containing psl-4 (Fig. 7A).

After finding that structures of psl motifs were highly conserved among three different viruses we were interested if the structure proposed to block dimerization of psl-1 at the 3′ end was also conserved. As for RD114, we predicted secondary structures of the 3′ ends of the BaEV and PcEV genomes. The Mfold program predicted similar long hairpin structures blocking formation of psl-1 hairpin for all three viruses (Fig. 7B).

DISCUSSION

In this work we have investigated the molecular basis for the unusually high melting temperature reported for dimeric RNA genomes isolated from virions of the endogenous cat gammaretrovirus RD114 >25 yr ago (Kung et al. 1975, 1976). We found that the uniquely high thermal stability could be reproduced for dimers of fragments of RD114 RNA generated by in vitro transcription. When similar lengths of 5′ end RNA fragments were used for RD114 and the mouse endogenous retrovirus Akv–MLV under the same dimerization and melting conditions, a melting difference of about 20°C was revealed. Multiple dimerization sites located from position 1 to 472 contribute to the high thermal stability of RD114 RNA. While RNA dimerization sites identified for other gammaretroviruses are all located outside R-U5 to a region of the 5′-leader also implicated in RNA packaging (Tounekti et al. 1992; Torrent et al. 1994; D'Souza et al. 2001), the sequences of the R region of RD114 RNA contributed to in vitro dimerization.

Our finding of RNA-dimerization motifs very close to the 5′ end as well as further downstream is in agreement with electron micrographs of virion RNA of RD114, where ∼600 bases were estimated to be included in the dimer linkage (Kung et al. 1975). These data revealed a parallel structure of RNA subunits with a Y- (or T-) shaped structure, referred to as the rabbit ears (RE) structure located close to the 5′ end. Depending on the condition (urea and formamide concentration, temperature) of probe preparation, the length of free RE ends varied, and on some micrographs the RE structure was closed.

We identified five psl motifs psl-1 to psl-5 as playing a role for in vitro dimerization of RD114 RNA. With the exception of psl-2, our analysis also predicted these stem-loop structures to be present in two endogenous baboon retroviruses (Mang et al. 1999; van der Kuyl et al. 1999) believed to represent ancestors of RD114. These data were supported by antisense oligonucleotide mapping and analyses of psl mutants. Psl-1 and psl-2 were located in R, psl-3 between U5 and the SD site, and psl-4 and psl-5 between SD and the AUG initiation codon of Gag. We found that mutations preventing potential kissing-loop interactions in different psl motifs reduce the melting temperature of the dimers, and that some of the mutations or their combinations influence dimerization efficiencies. This observation favors the assumption that all five proposed motifs participate in RD114 RNA dimerization and contribute to the high thermostability of dimers. Among all solitary mutations the most drastic effect on the thermostability of dimers was exerted by the psl-4 mutation in RNA 280–591. Reduction of the melting temperature of up to 20°C might suggest that psl-4 is a core signal for RD114 dimerization. On the other hand, combinations of mutations in psl-1-2-3 or psl-4-5 had an approximately similar influence on full-length leader RNA dimer stability. Moreover, mutations of psl sites located upstream of SD had a more prominent effect on the dimerization efficiency. Thus, further experiments, probably also including native virion RNA, will be necessary to dissect the particular role of each psl site in the dimerization of RD114 viral RNA.

We observed prominent formation of oligomeric RNA forms, especially when the three most upstream psl motifs were present. Oligomer formation in vitro is most likely supported by the presence of multiple dimerization sites and the use of specific conditions that induce dimerization. However, the occurrence of these forms in vivo as well as their physiological role seem less probable. One intriguing suggestion may by a possible role of NC protein in the inhibition of the formation of such oligomeric forms in vivo.

While dimerization of short fragments of retroviral RNA in vitro is rather effective, this is not the case for longer transcripts. A decrease in dimer formation with stepwise increase of RNA length from 400 up to 1200 bp for Mo–MLV RNA was shown (Flynn and Telesnitsky 2005). Similar results were obtained for Akv virus (S Kharytonchyk and FS Pedersen, unpubl.). In contrast, we have not observed decreasing dimerization efficiency for longer fragments of RD114 RNA, and a fragment as long as 1367 bp can be completely dimerized (Fig. 1B).

Interestingly, the most stable dimer with a melting temperature in water of 72.5°C was observed for RNA fragments covering nucleotides 280–472 and 280–591 between the SD site and the AUG of Gag and containing only two of the five identified psl motifs. The high stability of this small RNA was unexpected when considering the much lower stability of overlapping fragments 153–591 and 153–472. 153–472 RNA is only 127 nucleotides longer than 280–472 RNA, but the difference in dimer stability between the two fragments was about 7.5°C. Sequences outside the dimer initiation site have been reported to influence the thermal stability of retroviral RNA dimers in some earlier studies. Data from HIV-1 provide examples of a decrease (Sakuragi and Panganiban 1997) or increase in stability (Marquet et al. 1994; Laughrea and Jetté 1996). The molecular mechanism(s) of these influences remain unknown. Moreover, dimers of different splice products of HIV-1 have different thermal stability, even though the same sequence is involved in dimerization (Sinck et al. 2007).

The high thermal stability of 72.5°C of the dimer formed with the 280–474 and 280–591 RNA fragments located between SD and Gag-AUG may be connected to a high G–C content of the psls and a resulting high number of intermolecular G–C base pairs in the dimer. Looking at the sequences of psl-4 and psl-5 we find a total of 22 base pairs potentially involved in dimerization, with 20/22 being G–C base pairs. Compared with the dimer linkage structure of Mo–MLV as proposed by D'Souza and Summers (2005), two psls (DIS 1 and 2) create 44 base pairs in the dimer including 20 G–C base pairs. On the other hand, 24/44 base pairs involved in forming the Mo–MLV dimer are non-G–C pairs, including eight noncanonic G–U, A–C, and U–U pairs. This high G–C content may contribute to the high thermal stability of RD114 RNA dimers. This high stability of RNA dimers determined by sequences downstream from the SD site in genomic RD14 RNA compared with other gammaretroviruses is further enhanced by additional upstream interactions involving psl-1, psl-2, and psl-3. The three motifs are all characterized by a high G–C content in the palindromic region with 8/12, 8/10, and 10/10 predicted base pairs of the dimer being G–C base pairs for psl-1, psl-2, and psl-3, respectively. Future studies may further address the role of high G–C content on the thermostability of RD114 RNA dimers.

RD114 is able to support the transmission of an MLV-derived vector (Sakaguchi et al. 2008). The leader region of RD114 RNA contains many motifs characteristic of prototypic gammaretroviruses such as Akv–MLV and Mo–MLV. Psl-3 and Psl-4 are positioned at the same distance from the primer binding site in RD114, as are two psls DIS-1 and DIS-2 of the MLVs. Moreover, two GACG-hairpins downstream from DIS-2 are implicated in the dimerization and packaging of MLV-RNA (Mougel and Barklis 1997; De Tapia et al. 1998; Fisher and Goff 1998; Kim and Tinoco 2000; Badorrek et al. 2006). Such GACG-hairpin motifs are also found in RD114 RNA (as well as in BaEV and PcEV), with GACG-sequences at nucleotide positions 336–339 and 371–375, respectively (see Fig. 4J). Interestingly, the SD site in RD114 is found between psl-3 and psl-4 at nucleotide 255, a position 107 nucleotides downstream from the PBS, whereas it is located just 42 nucleotides downstream from the PBS in MLV. In both viruses the SD site has the sequence AGGT. The biological significance of this difference in SD position, if any, is not clear.

Dimer linkage signals (DLS) upstream of the SD site have previously been described for lentiviruses such as HIV-1, HIV-2, Maedi Visna virus (Monie et al. 2005), and probably feline immunodeficiency virus (James and Sargueil 2008). To our knowledge, RD114 is the first virus outside the lentiviruses found to have a DLS upstream of the SD site. In vitro heterodimerization of spliced RNA forms with genomic RNA was previously shown for HIV-1 (Sinck et.al. 2007) as well as packaging and replication of these spliced RNAs (Liang et al. 2004; Houzet et al. 2007). Studies of the dimerization and packaging of spliced RD114 RNA are ungoing.

The R region of HIV-1 has been proposed to be involved in RNA dimerization with intermolecular base-pairing of nucleotides of the trans-activation response (TAR) element (Chang and Tinoco 1994; Andersen et al. 2004). The results reported here raise the possibility of a similar role of the psls in the R region of RD114 RNA. As discussed in the case of HIV (Andersen et al. 2004), hairpin motifs in the R region may also play an alternative role in template switching during reverse transcription, where minus strand strong stop becomes extended into U3 after template switching. We note that the interesting possibility of forming tetrameric TAR interactions among the four R regions in an HIV-1 RNA dimer (Andersen et al. 2004) or the formation of dimers between 3′ R sequences is less likely in the case of RD114, since we found R sequences linked to U3 to be impaired in formation of RNA dimers. Secondary structure prediction points to a similar mode of regulation in two endogenous baboon retroviral ancestors of RD114.

In summary, we report that the high melting temperature of virion RNA dimers of the gammaretrovirus RD114 is determined by specific stem–loop structures in the 5′ untranslated region of the RNA. In addition to this high thermostability, our in vitro studies have identified features of RD114 RNA not previously reported for other gammaretroviruses such as multiple dimerization signals, with part of them upstream of major SD site and U3 sequence inhibited dimerization of R sequences. In vivo studies of individual steps in the replication of RD114 are needed to further address the possible regulatory roles of these features of RD114 RNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cell lines

A plasmid containing the complete genome of the infectious RD114 virus isolate SC3C (Reeves and O'Brien 1984; Cosset et al. 1995) was kindly provided by Drs. F.-L. Cosset and Y. Takeuchi. The nucleotide sequence of the RD114 SC3C isolate was retrieved from NCBI GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), accession no. EU030001. The cell line D17 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CCL183).

Mapping of RD114 splice site

D17 cells (5 × 106) were cotransfected with 8 μg of RD114 genome containing plasmid and 2 μg of pIRES EGFP (Clontech) by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. Cells were harvested after 3 wk of passages and total cellular RNA was isolated using the PARIS kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed with RD114 env-specific primer RD-5′ env rev (see Table 5) and RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RD114 cDNA was amplified using primers exT7pro-R-RD114 and RD-5′ env rev (Table 5). The PCR product was directly sequenced with BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems).

TABLE 5.

Primers used in this study

Plasmid construction

pT7RD114 + 1–1367

A 1367-bp fragment of the RD114 SC3C genome (positions from +1 to 1367), was amplified with primers exT7pro-R-RD114 and RD114-gag rev, and then reamplified with primers MfeI-exT7pro and RD114-gag rev (Table 5). The amplified fragment was digested with MfeI and cloned into the EcoRI–HincII sites of plasmid pUC19. pT7RD114 + 1–1367 contains a fragment of the RD114 genome from position +1, including R, U5, leader region, and part of gag to position 1367 under control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. Transcription driven by T7 RNA polymerase produces RD114 RNA from position +1 with one additional G at the 5′ end.

Plasmids with mutations

Nine plasmids with mutations in different psl sites and their combinations (described in the text) were constructed on the basis of pT7RD114 + 1–1367 by re-cloning of amplified DNA fragments with corresponding mutations. All mutations were part of the designed PCR primers. Sequences of the primers and the scheme of the construction will be available upon request. Correct structures of all plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

RNA in vitro synthesis and purification

In vitro transcription was performed using AmpliScribe T7 kit (Epicentre Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Linearized plasmid or amplified DNA was used as a template for in vitro transcription. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 0.5% TBE buffer and purified using Illustra GFX PCR DNA and a Gel Band Purification kit (GE Healthcare). After purification amplified DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme before in vitro transcription, except for the short template for 1–60 RNA, which was used directly from PCR mix.

For synthesis of different RNA fragments from pT7RD114 + 1–1367, plasmid DNA was linearized with: HindIII (at a site in the pUC19 vector 17 bp downstream from cloned RD114 fragment) for synthesis of 1–1367 RNA; BamHI for synthesis of 1–799 RNA; NcoI for synthesis of 1–591 RNA; SacII for synthesis of 1–472 RNA; EcoRI for synthesis of 1–288 RNA; SmaI for synthesis of 1–201 RNA, or AvrII for synthesis of 1–107 RNA.

All primers used for PCR generation of templates for in vitro transcription are listed in Table 1. The template for synthesis of RNA corresponding RD114 R region (positions 1–60) was amplified with primers exT7pro-RD-153 and RD-R rev. The template for synthesis of RNAs beginning from position 153 was amplified with primers exT7pro-RD-153 and RD114-gag rev. After purification DNA was digested with NcoI for synthesis of 153–591 RNA; SacII for synthesis of 153–472 RNA, or EcoRI for synthesis of 153–288 RNA. The template for synthesis of RNA beginning from position 280 was amplified with primers exT7pro-RD-280 and RD114-gag rev. Amplified DNA was digested with NcoI for synthesis of 280–591 RNA or with SacII for synthesis of 280–472 RNA. The template for synthesis of RNAs beginning from position 317 was amplified with primers exT7pro-RD-317 and RD114-gag rev. After purification DNA was digested with NcoI for synthesis of 317–591 RNA or HincII for synthesis of 317–515 RNA. The template for synthesis of RNAs beginning from position 472 was amplified with primers exT7pro-RD-472 and RD114-gag rev. After purification DNA was digested with BamHI for synthesis of 472–799 RNA or NcoI for synthesis of 472–591 RNA. The template for synthesis of the antisense leader RNA from position +512 to position +1 was generated with primers RD-R dir and exT7pro-RD anti512. The template for the synthesis of RNA mimicking the 3′ end of RD114 RNA genome from position 7550 to 7984 was generated with primers exT7pro-RD-ppt and RD-R rev. The template for synthesis of RNA mimicking the 3′ end of RD114 RNA genome from position 7852 to 7984 was generated with primers exT7pro-RD-U3-283 and RD-R rev.

The template for synthesis of 1–638 Akv murine retrovirus RNAs was generated by amplification of plasmid pAKVPro contained the full-length genome of Akv (Aagaard et al. 2004; Acc. No J01998) with primers exT7proRdir and Akv 5′UTRrev. Sense primer exT7proRdir (AATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCGCCAGTCCTCCGATAGAC) contained the sequence of the T7 polymerase promoter and adjacent Akv sequence beginning from position +1. Antisense primer Akv 5′ UTRrev was fully complementary to the Akv genome sequence positions + 638–615 (CGTTTTTAGAAGCGGTCCAAAAC). In vitro transcription by T7 polymerase generated a fragment of Akv genomic RNA from position +1 to 638 with one additional G at the 5′ end.

In vitro transcription was stopped by incubation of the probes with DNase I at 37°C 15 min. RNA was purified on affinity columns of the RNA Clean-up Kit-25 (Zymo Reaserch) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was eluted with 50 μL of RNase-free water and kept on ice. For the study of cotranscriptional RNA dimerization, aliquots of transcription mix were kept on ice before further analysis.

In vitro dimerization assay

In a typical experiment RNA was denatured for 2 min at 90°C and immediately snap-cooled on ice. Then the samples were incubated for 20 min at 50°C in dimerization buffer (Tounekti et al. 1992; final concentration: 50 mM sodium cacodylate at pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Samples were loaded onto a 1% nondenaturing agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Gels were run in 0.5× TBE buffer at 4°C with appropriate size markers of dsDNA or ssRNA. RNA was visualized by UV and analyzed with Chemidoc (Bio-Rad) software.

To determine the thermal stability of the dimer species, aliquots of dimerized samples were either diluted 10 times in RNase-free water and incubated at different temperatures gradually increased by 5°C steps from 70°C to 85°C or purified on affinity columns as described above, and aliquots incubated at different temperatures gradually increased by 5°C steps from 55°C to 80°C. After 10-min incubation at the indicated temperature, an aliquot was loaded on a 1% agarose gel and electrophoresed. Antisense oligonucleotide probing experiments were performed in the same way, except that 10-fold molar excess antisense DNA oligonucleotides were added after heat denaturation of RNA samples. Sequences of antisense DNA oligonucleotides are presented in Table 2.

All dimerization experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Mfold RNA secondary structure prediction and structural alignment

RNA secondary structure prediction was performed with Mfold version 3.2 algorithm (Zuker 2003) on the RNA folding server (http://mfold.bioinfo.rpi.edu/cgi-bin/rna-form1.cgi) and analyzed with standard settings. Structural alignment of the leader regions of RD114, BaEV clone M7 (sequence accession number D10032) and PcEV (accession number AF142988) was performed with SCARNA software (Tabei et al. 2006) on the SCARNA web server (http://www.scarna.org/).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. F.-L. Cosset and Y. Takeuchi for providing the RD114 genome and Lars Aagaard and Ebbe Sloth Andersen for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research and by Fabrikant Vilhelm Pedersen og Hustrus Legat.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1495110.

REFERENCES

- Aagaard L, Rasmussen SV, Mikkelsen JG, Pedersen FS. Efficient replication of full-length murine leukemia viruses modified at the dimer initiation site regions. Virology. 2004;318:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ES, Contera SA, Knudsen B, Damgaard CK, Besenbacher F, Kjems J. Role of the trans-activation response element in dimerization of HIV-1 RNA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22243–22249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badorrek CS, Gherge CM, Weeks KM. Structure of an RNA switch that enforces stringent retroviral genomic RNA dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:13640–13645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606156103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basyuk E, Boulon S, Skou Pedersen F, Bertrand E, Vestergaard Rasmussen S. The packaging signal of MLV is an integrated module that mediates intracellular transport of genomic RNAs. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W, Davidson N. Mapping of poly(A) sequences in the electron microscope reveals unusual structure of type C oncornavirus RNA molecules. Cell. 1976;7:595–607. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W, Chien YH, Chattopadhyay S, Vogt PK, Gardner MB, Davidson N. Highmolecular-weight RNAs of AKR, NZB, and wild mouse viruses and avian reticuloendotheliosis virus all have similar dimer structures. J Virol. 1978;25:888–896. doi: 10.1128/jvi.25.3.888-896.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KY, Tinoco I., Jr Characterization of a “kissing” hairpin complex derived from the human immunodeficiency virus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:8705–8709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosset FL, Takeuchi Y, Battini JL, Weiss RA, Collins MK. High-titer packaging cells producing recombinant retroviruses resistant to human serum. J Virol. 1995;69:7430–7436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7430-7436.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlix JL, Gabus C, Nugeyre MT, Clavel F, Barré-Sinoussi F. Cis elements and transacting factors involved in the RNA dimerization of the human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:689–699. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90392-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tapia M, Metzler V, Mougel M, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C. Dimerization of MoMuLV genomic RNA: Redefinition of the role of the palindromic stem–loop H1 (278–303) and new roles for stem–loops H2 (310–352) and H3 (355–374) Biochemistry. 1998;37:6077–6085. doi: 10.1021/bi9800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza V, Summers MF. How retroviruses select their genomes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:643–655. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza V, Melamed J, Habib D, Pullen K, Wallace K, Summers MF. Identification of a high affinity nucleocapsid protein binding element within the Moloney murine leukemia virus Psi-RNA packaging signal: Implications for genome recognition. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:217–232. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Goff SP. Mutational analysis of stem–loops in the RNA packaging signal of the Moloney murine leukemia virus. Virology. 1998;244:133–145. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JA, Telesnitsky A. Two distinct Moloney murine leukemia virus RNAs produced from a single locus dimerize at random. Virology. 2005;344:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Rein A. Maturation of dimeric viral RNA of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1993;67:5443–5449. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5443-5449.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Gorelick RJ, Rein A. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 dimeric RNA from wild-type and protease-defective virions. J Virol. 1994;68:5013–5018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5013-5018.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greatorex J. The retroviral RNA dimer linkage: Different structures may reflect different roles. Retrovirology. 2004;1:22. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert CS, Mirro J, Rein A. mRNA molecules containing murine leukemia virus packaging signals are encapsidated as dimers. J Virol. 2004;78:10927–10938. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10927-10938.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houzet L, Morichaud Z, Mougel M. Fully-spliced HIV-1 RNAs are reverse transcribed with similar efficiencies as the genomic RNA in virions and cells, but more efficiently in AZT-treated cells. Retrovirology. 2007;4:30. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WS, Temin HM. Genetic consequences of packaging two RNA genomes in one retroviral particle: Pseudodiploidy and high rate of genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James L, Sargueil B. RNA secondary structure of the feline immunodeficiency virus 5′UTR and Gag coding region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4653–4666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Tinoco I., Jr A retroviral RNA kissing complex containing only two G–C base pairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9396–9401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170283697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SR, Duggal NK, Ndongmo CB, Pacut C, Telesnitsky A. Pseudodiploid genome organization AIDS full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA synthesis. J Virol. 2008;82:2376–2384. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02100-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HJ, Bailey JM, Davidson N, Nicolson MO, McAllister RM. Structure, subunit composition, and molecular weight of RD-114 RNA. J Virol. 1975;16:397–411. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.2.397-411.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HJ, Hu S, Bender W, Bailey JM, Davidson N, Nicolson MO, McAllister RM. RD-114, baboon, and woolly monkey viral RNA's compared in size and structure. Cell. 1976;7:609–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughrea M, Jetté L. Kissing-loop model of HIV-1 genome dimerization: HIV-1 RNAs can assume alternative dimeric forms, and all sequences upstream or downstream of hairpin 248–271 are dispensable for dimer formation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1589–1598. doi: 10.1021/bi951838f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Hu J, Russell RS, Kameoka M, Wainberg MA. Spliced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA is reverse transcribed into cDNA within infected cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:203–211. doi: 10.1089/088922204773004923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang R, Goudsmit J, van der Kuyl AC. Novel endogenous type C retrovirus in baboons: Complete sequence, providing evidence for baboon endogenous virus gag-pol ancestry. J Virol. 1999;73:7021–7026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.7021-7026.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquet R, Paillart JC, Skripkin E, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. Dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA involves sequences located upstream of the splice donor site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:145–151. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monie TP, Greatorex JS, Maynard-Smith L, Hook BD, Bishop N, Beales LP, Lever AM. Identification and visualization of the dimerization initiation site of the prototype lentivirus, maedi visna virus: A potential GACG tetraloop displays structural homology with the alpha- and gammaretroviruses. Biochemistry. 2005;44:294–302. doi: 10.1021/bi048529m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougel M, Barklis E. A role for two hairpin structures as a core RNA encapsidation signal in murine leukemia virus virions. J Virol. 1997;71:8061–8065. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8061-8065.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe H, Gilden RV, Hatanaka M. RD 114 virus-specific sequences in feline cellular RNA: Detection and characterization. J Virol. 1973;12:984–994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.12.5.984-994.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Conde BA, Hughes SH. Studies of the genomic RNA of leukosis viruses: Implications. for RNA dimerization. J Virol. 1999;73:7165–7174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7165-7174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillart JC, Marquet R, Skripkin E, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. Dimerization of retroviral genomic RNAs: Structural and functional implications. Biochimie. 1996;78:639–653. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(96)80010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillart JC, Shehu-Xhilaga M, Marquet R, Mak J. Dimerization of retroviral RNA genomes: an inseparable pair. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:461–472. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves RH, O'Brien SJ. Molecular genetic characterization of the RD-114 gene family of endogenous feline retroviral sequences. J Virol. 1984;52:164–171. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.164-171.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Okada M, Shojima T, Baba K, Miyazawa T. Establishment of a LacZ marker rescue assay to detect infectious RD114 virus. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70:785–790. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi JI, Panganiban AT. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA outside the primary encapsidation and dimer linkage region affects RNA dimer stability in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:3250–3254. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3250-3254.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagulova F, Maurel S, Morichaud Z, Devaux C, Mougel M, Houzet L. The highly structured encapsidation signal of MuLV RNA is involved in the nuclear export of its unspliced RNA. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:1118–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinck L, Richer D, Howard J, Alexander M, Purcell DF, Marquet R, Paillart JC. In vitro dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) spliced RNAs. RNA. 2007;13:2141–2150. doi: 10.1261/rna.678307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabei Y, Tsuda K, Kin T, Asai K. SCARNA: Fast and accurate structural alignment of RNA sequences by matching fixed-length stem fragments. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1723–1729. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrent C, Gabus C, Darlix JL. A small and efficient dimerization/packaging signal of rat VL30 RNA and its use in murine leukemia virus-VL30-derived vectors for gene transfer. J Virol. 1994;68:661–667. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.661-667.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tounekti N, Mougel M, Roy C, Marquet R, Darlix JL, Paoletti J, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C. Effect of dimerization on the conformation of the encapsidation Psi domain of Moloney murine leukemia virus RNA. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:205–220. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90726-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kuyl AC, Dekker JT, Goudsmit J. Discovery of a new endogenous type C retrovirus (FcEV) in cats: Evidence for RD-114 being an FcEV(Gag-Pol)/baboon endogenous virus BaEV(Env) recombinant. J Virol. 1999;73:7994–8002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.7994-8002.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]