Abstract

Background and Aims

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) has played an important role in establishing a linkage between lower body function and health in community dwelling older adults. It has had limited use in hospitalized elders, however. The objectives of this study were to determine if SPPB information could be reliably collected in a hospitalized older patient population, and compare SPPB scoring criteria previously established in a community population to a hospitalized population.

Methods

A cross sectional design that included 90 adults aged 65 years or older admitted to an Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit. Patient information was collected within 24 hours of hospitalization. SPPB was scored using established criteria for older persons in the community and revised criteria for older persons hospitalized with acute illness.

Results

The mean age of the sample was 75.3 (SD 7.1) years, 61% were women, and 67.8% were non-Hispanic white, 21.2% non-Hispanic black and 11% Hispanic. Mean hospital and community SPPB scores were 4.9 (SD 3.5) and 3.6 (SD 2.9), respectively. In multivariate regression analyses, increasing age (b= −0.15, SE 0.06, p=0.007), length of stay (b= −0.36, SE 0.15, p=0.02), comorbidities (b= −0.36, SE 0.16, p=0.04), and cognition (b= −2.94, SE 1.25, p=0.02) were significantly and inversely associated with hospital SPPB. Only age (b= −0.11, SE 0.05, p=0.02) was significantly associated with community SPPB.

Conclusions

This study showed that the SPPB can be reliably collected in hospitalized older patients. The study further suggests that revised hospital SPPB scoring criteria may be appropriate when used in this older population.

Keywords: aged, geriatric assessment, patients, health status indicators

Introduction

The Short Physical Performance Battery is comprised of 3 objective tests of lower body function: a timed walk, repeated chair stands, and standing balance. The Short Physical Performance Battery has been used extensively in community dwelling older adults to assess physical and functional health (1, 2). Research has shown that poor performance on the Short Physical Performance Battery is associated with adverse health outcomes such as nursing home placement, increased need for caregiver support, functional decline, and mortality (3, 4). Scoring methods for the Short Physical Performance Battery were developed from large epidemiological investigations of relatively healthy older men and women living at home (3). Criteria based on community populations may not be optimal for use in inpatient settings (5).

The Short Physical Performance Battery has had limited use in hospitalized older patients. In a recent study, Quadri (6) investigated lower body functioning of 144 hospitalized older adults within 48 hours of discharge from a general internal medicine ward. Although the study excluded the frailest patients, those who scored poorly on the Short Physical Performance Battery were at significantly increased risk for falls, nursing home placement, and loss of independence at a 1 year follow up.

Further evaluation of the Short Physical Performance Battery in hospitalized older patients is important for several reasons. First, recent national hospital discharge surveys indicate the elderly will be major consumers of inpatient health care in the coming decades. For example, those 65 or older compromised only 12.7% of the population in 2005, yet they accounted for almost 38% of all hospital admissions and used 44% of total days of care (7). Second, targeting high risk patients has been shown to be a key factor in optimizing outcomes during hospitalization (e.g., length of stay, falls, declines in function) and post discharge (8, 9). Between 30–50% of patients aged 65 or older lose some lower body function while hospitalized, and these declines can occur as early as the second day (10). Following discharge, loss of lower body function is associated with higher health resource use, institutionalization, further functional declines, and death (11). Third, objective measures of lower body function are increasingly recognized as basic indicators of health in older people (5). This could be especially relevant in the context of acute illness and hospitalization. While physiologic markers of health status generally improve and normalize by discharge (12), lower body function can vary considerably (13), making it a useful indicator of overall well-being and recovery.

A goal of the current investigation was to further examine the feasibility and patient acceptance of a Short Physical Performance Battery in a broad sample of older adults hospitalized for acute illness. A second goal of the investigation was to assess associations between Short Physical Performance Battery scores with sociodemographic characteristics and clinical measures.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

Eligible patients included those aged 65 or older admitted from the community to a university teaching hospital with an acute medical event. All patients reported they were able to walk across a small room without the assistance of another person prior to admission. Of the 111 patients who agreed to participate and were eligible for inclusion into the study, 9 later refused, 7 were discharged prior to performing the Short Physical Performance Battery assessment and 4 were removed due to missing sociodemographic or clinical data. There were non-significant differences between the 21 patients excluded from the study and the remaining sample across sociodemographic and clinical measures included in the analysis. The final sample included 90 patients.

Interviewers trained in clinical research techniques collected sociodemographic and clinical measures within 24 hours of admission. Face-to-face interviews were performed in a single session in the patient’s hospital room followed by a review of the patient’s chart. A Short Physical Performance Battery (see description below) was assessed by a licensed physical therapist after completion of the interview. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained at the time of the interview.

Outcome Measure

Short Physical Performance Battery

The Short Physical Performance Battery includes three objective tests of lower body function: (1) a timed 8-foot walk; (2) 5 timed, repetitive chair stands; and (3) a hierarchical test of standing balance. For each test a 5-level summary scale (0–4) was assigned. A zero score indicates “unable to perform.” Subjects in the “unable to perform” category included: (1) those who tried but were unable; (2) the interviewer or subject felt it was unsafe; or (3) unable for other health reasons (e.g., too ill, excessive monitoring equipment). A score of 1–4 represents the hierarchical performance of those able to perform the test according to specific cut-points described below.

8-foot walk

Gait speed was measured over a distance of 2.4 meters (8 feet), and use of an assistive device (e.g., cane or walker) was allowed. Patients were asked to walk at their normal pace from a standing position. Timing began when the patient was told “go” and ended when the 2.4 meter mark was crossed. Categorical scores (1–4) were based on previously established quartiles of timed performance according to methods developed by Guralnik et al (3).

Chair stands

To test the ability to rise from a regular height, straight-backed chair, patients were asked to complete five repetitive chair stands as quickly as possible after first demonstrating the ability to rise once from a chair with arms folded across their chests. Categorical scores (1–4) were based on previously established quartiles of timed performance according to methods developed by Guralnik et al (3).

Standing balance

For the standing balance task, patients were first asked to place their feet in a side-by-side position, followed by a semi-tandem position (heel of one foot alongside the big toe of the other foot) and tandem position (heel of one foot directly in front of the other foot). Patients were required to hold the side-by-side position for 10 seconds in order to advance to the semi-tandem task; to advance to the tandem task the semi-tandem position needed to be held for 10 seconds. Categorical scores (1–4) were based on previously established criteria developed by Guralnik et al (3).

Short Physical Performance Battery summary scores were created by summing the 3 individual test items (8- foot walk, chair stands, and balance test). There was a potential range of 0–12, with higher scores indicating better lower body function. Short Physical Performance Battery summary scores were modeled as a continuous measure for all analysis.

Independent Measures

Sociodemographic measures included gender, age (continuous), marital status (married vs unmarried), level of education (< high school vs ≥ high school) and ethnicity (descriptive statistics are provided for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanic; for the regression analysis, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic were collapsed, creating a dichotomous variable, non-Hispanic white vs other). Clinical measures included a summary comorbidity index (heart attack, stroke, cancer, diabetes, hip fracture after age 50, and respiratory distress), length of stay (continuous in days), body mass index (<22, 22–29.9, ≥30), self-rated level of pain (ranging from 0, no pain to 10, worst pain possible), cognition, and depression. Cognition was assessed using 10 items from the Short Portable Mental Health Questionnaire (SPMHQ) (14): 0–2 errors = intact functioning; >2 = impaired). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale (15). The CES-D included 20 items and individuals were asked whether they had experienced certain feelings or symptoms in the past week. Scores for the CES-D ranged from 0 to 60 where higher scores indicate increased depressive symptoms. In the analysis, the CES-D scale was used as a categorical variable (0–15 and ≥ 16). Patients with scores of 16 or more were classified as having high depressive symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as means (and standard deviations) for continuous measures and as percentages for categorical measures. Four generalized linear regression models we developed to compare associations between community and hospital Short Physical Performance Battery scores and sociodemographic and clinical measures. Community and hospital Short Physical Performance Battery regression models were first adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and education), and then for clinical measures (cognition, comorbidities, length of stay, body mass index, pain report, and depressive symptoms). For all regression models, testing was 2-sided using an alpha of 0.05. Standard regression diagnostics were tested for assumptions related to linear regression and all assumptions were met. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 75.6 years (SD = 7.1; range, 65–92y). The majority of patients were female (61.8%) and not married (60.7%). Approximately 65.0% had at least a high school education. Most were non-Hispanic white (67.8%), followed by non-Hispanic black (21.2%), and Hispanic (11.0%). Approximately 92% of patients reported at least 1 comorbidity with an overall mean comorbidity index of 2.2 (SD = 1.4). The mean length of stay was 4.1 (SD = 2.4) days. Body Mass Index ranged from 17 to 57.0 with a mean of 27.3 (SD = 7.1). Among those who reported pain (24.7% of the sample), the mean pain score was 4.4 (SD = 3.0). High depressive symptoms were reported in 35.9% of the sample, and 10.1% of the sample had some cognitive impairment (SPMHQ ≥ 3).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to the Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit.

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD | Range | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 75.6 ± 7.1 | 65–92 | 90 | |

| Female | 55 | (61.1) | ||

| Race | ||||

| non-Hispanic White | 61 | (67.8) | ||

| non-Hispanic Black | 19 | (21.2) | ||

| Hispanic | 10 | (11.0) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Unmarred | 54 | (60.7) | ||

| Education | ||||

| ≥ High school | 58 | (64.4) | ||

| Length of Stay (days) | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 1–12 | ||

| Comorbidities | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 0–7 | ||

| Body Mass Index | 27.3 ± 7.1 | 17–57 | ||

| < 22 | 13 | (14.4) | ||

| 22 – 29.9 | 25 | (27.8) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 52 | (57.8) | ||

| Pain | *4.4 ± 3.0 | *1–10 | ||

| 0 (no pain) | 67 | (74.4) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 23 | (25.6) | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| CES-D (≥ 16) | 33 | (36.7) | ||

| Cognitive Impairment | ||||

| SPMHQ;≥ 3 | 9 | (10.0) | ||

Among those who reported pain.

Table 2 shows test performance for the timed 8-foot walk and repeated chair stands; the percentage of those unable to complete the task; the mean times, percentile times, and quartiles used to define categories (1–4) for those completing the task. The table compares previously published data by Guralnik et al (3) from a community based population of older adults to the results from our sample of older hospitalized patients. Hospitalized older adults required more time to complete the 8-foot walk and repeated chair stands and at least twice as many were unable to complete either task (score of 0) compared with the community sample.

Table 2.

Comparison of community and hospital based test performance for the timed 8-foot walk and repeated chair stands.

| 8-ft (2.4-m) walk |

Repeated chair stands |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community* | Hospital | Community* | Hospital | |

| Unable to complete | 4.9% | 9.0% | 21.6% | 57.3% |

| Times (sec) | ||||

| Mean | 5.0 | 7.8 | 14.5 | 22.9 |

| 1st percentile | 19.0 | 27.6 | 30.0 | 55.0 |

| 5th percentile | 10.3 | 18.4 | 23.2 | 45.0 |

| 10th percentile | 7.9 | 14.2 | 20.4 | 43.2 |

| 25th percentile** | 5.7 | 9.1 | 16.7 | 27.3 |

| 50th percentile** | 4.1 | 6.8 | 13.7 | 18.9 |

| 75th percentile** | 3.2 | 4.1 | 11.2 | 16.8 |

| 90th percentile | 2.7 | 3.4 | 9.5 | 11.0 |

| 95th percentile | 2.4 | 3.1 | 8.6 | 10.2 |

| 99th percentile | 2.0 | 2.3 | 6.7 | 8.0 |

Table 3 shows performance category percentages for the standing balance measure from the community and hospital based samples. For hospitalized older adults, only 15.7% could perform the most challenging balance task (tandem stance for 10 seconds) compared to 49.2% of older adults tested in the community. Almost 36% of patients were unable to maintain the side-by-side stance (score of 0) without upper extremity support compared to only 9.5% of community older adults. Score categories 2 and 3 had approximately equal percentages of patients in each: 10% and 11%, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison of community and hospital based performance category percentages for the standing balance measure.

| Community* | Hospital | |

|---|---|---|

| % of subjects | ||

| Category | ||

| 0 | 9.5 | 35.9 |

| 1 | 14.5 | 27.0 |

| 2 | 13.0 | 10.1 |

| 3 | 13.8 | 11.2 |

| 4 | 49.2 | 15.7 |

From Guralnik et al (3)

Because performance on all 3 tests (timed walk, repeated chair stands, and standing balance) for hospitalized older adults was much lower than that of community dwelling older adults, we created new cut points based on the performance of our sample using the methodology established by Guralnik et al (3). The hospital based cut points we developed and the community based cut points for the 3 tests are shown in Table 4. Original cut points for the standing balance test achieved the intended distribution of approximately equal number of persons in categories 2 and 3 in our sample.

Table 4.

Categories assigned to performance on the 8-foot walk, chair stands, and balance measure for those able to complete the task.

| Categorical Scores |

||

|---|---|---|

| Test | * Community | Hospital |

| 8-foot walk | ||

| 1 | ≥ 5.7 sec | ≥ 9.1 sec |

| 2 | 4.1–5.6 sec | 6.8–9.0 sec |

| 3 | 3.2–4.0 sec | 4.1–6.8 sec |

| 4 | ≤ 3.1sec | ≤ 4.0 sec |

| Chair Stands | ||

| 1 | > 16.7 sec | ≥ 27.3 sec |

| 2 | 13.7–16.6 sec | 18.9–27.2 sec |

| 3 | 11.2–13.6 sec | 16.8–18.8 sec |

| 4 | ≤ 11.1 sec | ≤ 16.7 sec |

| Standing Balance | ||

| 1 | Held SBSa stand for 10 sec but unable to hold STb stand for 10 sec | Held SBSa stand for 10 sec but unable to hold STb stand for 10 sec |

| 2 | Held STb stand for 10 sec but unable to hold FTc stand for >2 sec | Held STb stand for 10 sec but unable to hold FTc stand for >2 sec |

| 3 | Held FTc stand for 3 to 9 sec | Held FTc stand for 3 to 9 sec |

| 4 | Held the FTc stand for 10 sec | Held the FTc stand for 10 sec |

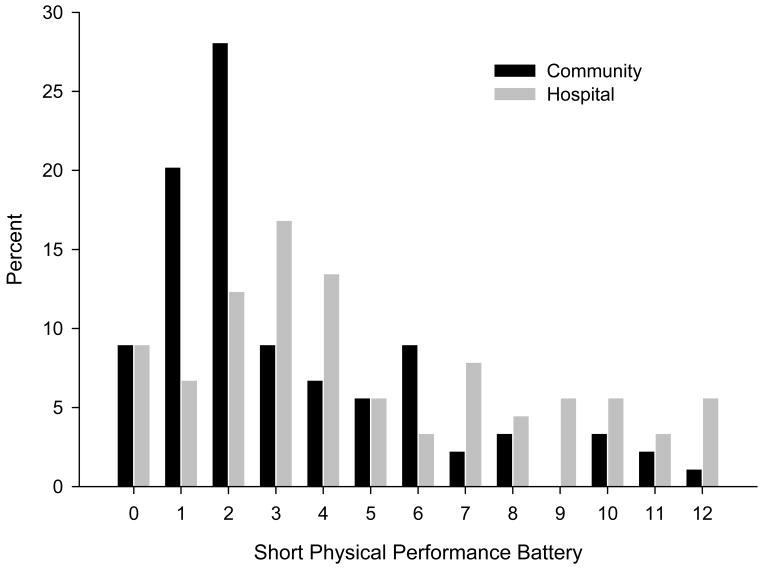

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Short Physical Performance Battery summary scores (0–12) for our sample, calculated using the original community based cut points and hospital based cut points that we constructed. The figure indicates that both distributions are skewed toward the low end of the range but more so for community older adults. Short Physical Performance Battery scores calculated using the original community based criteria ranged from 0 to 12, with a mean of 3.6 (SD = 2.9), a median of 2.0, and interquartile range of 4. Short Physical Performance Battery scores calculated using the hospital criteria ranged from 0 to 12, with a mean of 4.9 (SD = 3.5), a median of 4.0 and interquartile range of 5. Overall, 9.0% of patients had a Short Physical Performance Battery score of zero (unable to perform any of the three performance tests).

Figure 1.

Short Physical Performance Battery summary score based on community and hospital scoring (n=90).

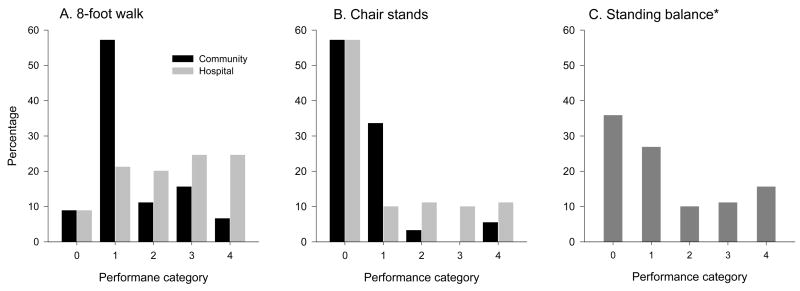

Figure 2 shows distributions for the three individual performance tests (8-foot walk, repeated chair stands, and standing balance) for our hospital sample calculated using the community based scoring criteria and the hospital scoring criteria. Figure 2A shows the distribution of the walking test. The figure indicates a more even distribution using hospital scoring criteria than community scoring criteria. For instance, approximately 57% of patients scored 1 using community scoring criteria compared with 21% using hospital scoring criteria. Of those able to perform the chair rise task, Figure 2B shows a better distribution of categorical scores using hospital scoring criteria. For the standing balance test (Figure 2C), similar procedures were used in calculating community and hospital categorical scores.

Figure 2.

Score category percentages for the timed walk, repeated chair rises, and standing balance measure.

*Community based scoring for the standing balance test achieved the intended distribution of approximately equal number of persons in categories 2 and 3.

Table 5 shows associations between continuous Short Physical Performance Battery summary score (0–12) and sociodemographic and clinical measures. Models 1 and 2 used community Short Physical Performance Battery scoring methods. Models 3 and 4 used hospital Short Physical Performance Battery scoring methods. In models 1 and 2, only increasing age (b= −0.12, SE 0.05, p=0.01) was significantly associated with community Short Physical Performance Battery. In Model 3, increasing age (b= −0.16, SE 0.05, p=0.003) was significantly associated with hospital Short Physical Performance Battery. In Model 4, increasing age (b= −0.15, SE 0.06, p=0.007), length of stay (b= −0.36, SE 0.15, p=0.02), comorbidities (b= −0.36, SE 0.16, p=0.04), and cognition (b= −2.94, SE 1.25, p=0.02) were significantly associated with the hospital Short Physical Performance Battery.

Table 5.

General linear regression models assessing the association between short physical performance battery based on community and hospital based scoring criteria and sociodemographic clinical characteristics (n=90).

| Short Physical Performance Battery (continuous) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Hospital | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

| b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | |

| Age (continuous) | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.003 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.007 |

| Men (vs Women) | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| White (vs non- White) | −0.70 | 0.64 | 0.28 | −0.90 | 0.67 | 0.18 | −0.41 | 0.77 | 0.59 | −0.76 | 0.78 | 0.33 |

| Married (vs unmarried) | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.93 | −0.31 | 0.76 | 0.68 | −0.50 | 0.49 | 0.59 |

| ≥ High school (vs < high school) | 0.87 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.65 | 0,66 | 0.33 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.47 |

| Length of stay (continuous) | * | −0.24 | 0.13 | 0.07 | * | −0.36 | 0.15 | 0.02 | ||||

| CES-Da <16 vs ≥ 16 | * | 1.05 | 0.66 | 0.12 | * | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.15 | ||||

| Comorbiditiesb (continuous) | * | −0.39 | 0.23 | 0.09 | * | −0.36 | 0.16 | 0.04 | ||||

| BMI (22–29.9) | ||||||||||||

| vs <22 | * | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.52 | * | 1.61 | 0.63 | 0.57 | ||||

| vs ≥30 | * | −0.03 | 0.74 | 0.97 | * | −0.29 | 0.86 | 0.74 | ||||

| Pain (0 vs ≥1) | * | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.77 | * | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.63 | ||||

| SPMHQc(0–2 vs ≥3 errors) | * | −1.85 | 1.08 | 0.09 | * | −2.94 | 1.25 | 0.02 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| R2=.11 | R2=.23 | R2=.13 | R2=.30 | |||||||||

Not included in model.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale.

Comorbidities included heart attack, stroke, cancer, diabetes, hip fracture (after age 50), and respiratory distress.

SPMHQ, Short portable mental health questionnaire.

The Short Physical Performance Battery assessment in this sample of older hospitalized adults was performed by a licensed physical therapist. The assessment took approximately 12 minutes to complete. No injuries or adverse events occurred and patient acceptance toward the measures was relatively high. We believe the timed nature of the 8-ft walk and repeated chair stands measure allowed patients to perform at an intensity they felt safe with. Monitoring equipment, supplemental oxygen, or IV poles did not prohibit participation in a particular test unless the physical therapist believed their presence would be unsafe for the patient.

Discussion

The objective of this study was twofold: first, to explore whether a Short Physical Performance Battery could be reliably collected in hospitalized older adults, and second, to compare Short Physical Performance Battery scoring based on previously established criteria in older community-dwelling persons with revised criteria based on hospitalized older patients. Our main findings can be summarized as follows. The Short Physical Performance Battery can be safely and reliably administered to hospitalized elderly patients. No injuries or adverse events occurred. Not unexpectedly, Short Physical Performance Battery scores were low in this sample population. Hospital Short Physical Performance Battery scoring criteria used to calculate the 8-foot walk and repeated chair stand measures better distributed the overall range of performance for older patients than community Short Physical Performance Battery scoring criteria. Multivariate regression analysis adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and clinical measures showed that older age, number or comorbidities, length of stay, and cognition were significantly associated with hospital Short Physical Performance Battery score. Only age reached statistical significance when the Short Physical Performance Battery score was calculated using community scoring criteria.

The Short Physical Performance Battery assesses the construct of lower body function with multiple measures and has played a vital role in establishing a linkage between lower body function and various health outcomes. In a study of 3,381 nondisabled community dwelling men and women aged 65 or older, low Short Physical Performance Battery performance significantly predicted subsequent hospitalization and mortality over 4 years. Poor lower body function was especially predictive of common geriatric conditions such as acute infections, pneumonia dehydration, and dementia (16). A recent study of 487 community dwelling veterans aged 65 or older found that the Short Physical Performance Battery was an independent predictor of hospitalization and decline in function even after accounting for baseline status, age, and physicians risk assessment (5). Other research in community environments has shown significant connections between performance on the Short Physical Performance Battery and various health outcomes including social isolation, the need for caregiver support, poor muscle strength, obesity, nursing home placement, and mortality (17–19).

Research examining the use of the Short Physical Performance Battery in an acute care hospital setting is limited. This in spite of evidence that, for the elderly, sufficient lower body ability must be present to recover functional status after hospitalization (2). The only other study using the Short Physical Performance Battery in a hospital setting of which we are aware found older adults who scored poorly on the Short Physical Performance Battery, assessed within 48 hour of discharge from a general internal medicine ward, were at significantly increased risk for falls, nursing home placement, and loss of independence 1 year later (6). The study only included patients able to perform the 3 lower body tests (i.e., they excluded patients who scored 0), and the assessment was performed by geriatricians on the unit. Our research suggests a score of zero on any of the 3 tests may potentially provide clinically relevant information. In a sub analysis, length of stay was 1.6 days longer for those patients who scored 0 on any of the 3 tests. Additionally, the inability to rise from a chair without upper extremity support appeared to be a good indicator of overall function. Further study on those unable to perform any of the three tests appears warranted, especially since our data shows that 95% of patients from our sample were discharged into the community.

Our investigation takes the next step in assessing the feasibility and acceptance of performing multiple measures of lower body function in a broad sample of older adults hospitalized for acute illness. The time required to complete the assessment was not excessive (approximately 12 minutes), and patients were not averse to attempting the timed walk, repeated chair stands, and standing balance measures. In this study, a licensed physical therapist performed all assessments; whether or not other health care providers such as nursing staff should administer the Short Physical Performance Battery will require additional research. In community based studies, trained interviewers typically administer the Short Physical Performance Battery, not licensed medical personnel.

This investigation has some limitations. First, findings were based on cross sectional data; thus, the trajectory of Short Physical Performance Battery performance across the hospital stay and post discharge was not assessed. Longitudinal data are needed to fully evaluate the clinical relevance of the SPPB using revised scoring criteria from a patient population. Second, this study does not address the question of whether the Short Physical Performance Battery is the best functional instrument for use in a hospital setting. A number of researchers (5, 20) have suggested that a standardized objective measure is needed to properly assess older patients and those at risk, but determining which measure (e.g., Short Physical Performance Battery vs gait speed alone vs ADLs) provides the best trade-off between clinical relevance and time invested administering the test will require further research. The Short Physical Performance Battery is an easily administered, reliable instrument and may be particularly suited for the hospital environment. Third, our study was a sample of convenience. However, men and women were equally represented; we included the three largest ethnic groups in the U.S.; and Short Physical Performance Battery scores were predictive of important sociodemographic characteristics and clinical measures.

In summary, this study demonstrated that the Short Physical Performance Battery can be safely collected in a sample of older patients. Further, the revised hospital Short Physical Performance Battery may be preferable in inpatient or institutional type settings (skilled nursing facilities, nursing homes) as scoring criteria were developed using the intended target population. Maintaining good functional ability in the older patient is one of the main goals of acute geriatric units. Thus, the benefits of routinely assessing the functional status of older patients are potentially enormous.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for S. Fisher (T32-HD07539), National Institutes of Health for K. Ottenbacher (K02-AG019736), J. Goodwin (P30-AG24832), and G. Ostir (K01-HD046682), and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133P040003) for J. Graham.

Funding sources: This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for S. Fisher (T32-HD07539), National Institutes of Health for K. Ottenbacher (K02-AG019736), J. Goodwin (P30-AG24832), and G. Ostir (K01-HD046682), and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133P040003) for J. Graham.

References

- 1.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrucci L, Penninx BW, Leveille SG, et al. Characteristics of nondisabled older persons who perform poorly in objective tests of lower extremity function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1102–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:314–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quadri P, Tettamanti M, Bernasconi S, Trento F, Loew F. Lower limb function as predictor of falls and loss of mobility with social repercussions one year after discharge among elderly inpatients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF03324578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2005;2007:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornette P, Swine C, Malhomme B, Gillet JB, Meert P, D’Hoore W. Early evaluation of the risk of functional decline following hospitalization of older patients: development of a predictive tool. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:203–208. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ, et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–1457. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortinsky RH, Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS. Effects of functional status changes before and during hospitalization on nursing home admission of older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M521–M526. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.10.m521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillenbaum GG. Comparison of two brief tests of organic brain impairment, the MSQ and the short portable MSQ. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1980;28:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1980.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penninx BW, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower extremity performance in nondisabled older persons as a predictor of subsequent hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M691–M697. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA, Goodwin JS. Lower body functioning as a predictor of subsequent disability among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M491–M495. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.6.m491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markides KS, Black SA, Ostir GV, Angel RJ, Guralnik JM, Lichtenstein M. Lower body function and mortality in Mexican American elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M243–M247. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.m243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K, Chaves PH, Johnson BA. Preclinical mobility disability predicts incident mobility disability in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M43–M52. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.m43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero-Odasso M, Schapira M, Varela C, et al. Gait velocity in senior people. An easy test for detecting mobility impairment in community elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]