Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent a large receptor family involved in a broad spectrum of cell signaling. To understand signaling mechanisms mediated by GPCRs in Phytophthora sojae, we identified and characterized the PsGPR11 gene, which encodes a putative seven-transmembrane GPCR. An expression analysis revealed that PsGPR11 was differentially expressed during asexual development. The highest expression level occurred in zoospores and was upregulated during early infection. PsGPR11-deficienct transformants were obtained by gene silencing strategies. Silenced transformants exhibited no differences in hyphal growth or morphology, sporangium production or size, or mating behavior. However, the release of zoospores from sporangia was severely impaired in the silenced transformants, and about 50% of the sporangia did not completely release their zoospores. Zoospore encystment and germination were also impaired, and zoospores of the transformants lost their pathogenicity to soybean. In addition, no interaction was observed between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1 with a conventional yeast two-hybrid assay, and the transcriptional levels of some genes which were identified as being negatively regulated by PsGPA1 were not clearly altered in PsGPR11-silenced mutants. These results suggest that PsGPR11-mediated signaling controls P. sojae zoospore development and virulence through the pathways independent of G protein.

All living organisms are exposed to the environment and respond to signals with appropriate cellular responses that are crucial for survival. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling is an evolutionarily conserved signal perception/processing system composed of three basic components: a seven-transmembrane (TM)-spanning G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR); a G protein heterotrimer consisting of α, β, and γ subunits; and effectors (29, 37). Ligands binding to the GPCR stimulate the exchange of GTP for GDP on the Gα subunit and the dissociation of the Gα and Gβγ dimer, which regulates downstream effector proteins in various systems, including ion channels, adenylyl cyclases, phosphodiesterases, and phospholipases (27, 36). GPCRs represent the largest family of plasma membrane-localized protein receptors and transmit a variety of environmental signals into the intracellular heterotrimeric G proteins (29, 52). Despite exhibiting striking diversity in primary sequence and biological function, all GPCRs possess a conserved fundamental architecture consisting of seven-transmembrane domains and share a mechanism of signal transduction.

The GPCR family is one of the largest receptor groups in most mammalian genomes. GPCRs are signal mediators that play a prominent role in most major physiological processes at both the central and the peripheral levels (21, 42). At present, only a few GPCRs have been identified in fungal genomes: three and four GPCRs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, respectively (2, 27), 10 receptors in Neurospora crassa (14), nine in Aspergillus nidulans (16), and more than 60 in Magnaporthe grisea and Cryptococcus neoformans (23, 31). Fungal GPCRs can be grouped into five classes based on sequence homology and ligand sensing: classes I and II include GPCRs similar to the Ste2/3 pheromone receptors, class III includes glucose sensor Gpr1 homologs, class IV includes nutrient sensor Stm1-like proteins, and class V includes homologs of the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptors in Dictyostelium discoideum (52). In fungi, two signaling branches defined by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) signal pathways and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades act downstream to relay G protein signaling and elicit cellular responses, including pheromones or nutrients (e.g., glucose or nitrogen starvation) (16, 32, 43, 51); cell growth (28); mating (22); cell division, cell-cell fusion, and morphogenesis (32, 35); and chemotaxis (27). Moreover, some pathogenic fungi rely on external stimuli to recognize their hosts (5, 10, 29, 49, 52).

The genus Phytophthora includes many plant pathogens that cause destructive diseases in a wide range of agriculturally and ornamentally important plants, resulting in multibillion-dollar cash crop losses worldwide (12, 48). For example, Phytophthora sojae (syn. Phytophthora megasperma f. sp. glycinea) is a devastating pathogen that causes losses of $1 to 2 billion per year worldwide by damping off seedlings and causing root rot in older plants (44). The disease is a serious problem in soybean-producing areas. Phytophthora ramorum is responsible for the disease sudden oak death and has destroyed many oak trees along the western coast of the United States (41). Despite its great economic importance, the basic biology of Phytophthora is still poorly understood, which limits the development of novel strategies for controlling the diseases that it causes.

Like all Phytophthora species, P. sojae produces sporangia, zoospores, and chlamydospores. Sporangia can germinate directly to produce hyphae or indirectly to produce 10 to 30 zoospores. Indirect germination involves differentiation of the sporangial cytoplasm, resulting in the formation of zoospores that are released through the sporangial apex. Zoospores are aquatic, lack a cell wall, and exhibit an α-helical swimming pattern. Moreover, zoospores are generally short lived (hours) and quickly differentiate to form adhesive cysts that germinate to produce hyphae or secondary zoospores (12, 44). P. sojae zoospores swim chemotactically toward compounds released by the roots of their host plants (47). Investigations into the molecular processes that underlie these events have shown that heterotrimeric G protein-mediating signaling pathways are of great importance in Phytophthora. For example, in Phytophthora infestans, silencing of the Gα subunit protein impairs directional swimming, chemotaxis, autoattraction, and zoospore pathogenicity; moreover, the Gβ subunit protein is important for sporangium formation and sporulation (25, 26). Recently, we found that the P. sojae Gα subunit protein is involved in zoospore behavior and chemotaxis to soybean isoflavones (18), but the receptor associated with the heterotrimeric G protein is less well understood. A bioinformatics analysis of the entire P. sojae genome indicated more than 24 GPCRs, of which two have a C-terminal intracellular phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase domain similar to the Dictyostelium RpkA gene (4).

The recent completion of P. sojae genome sequencing and the development of effective molecular genetic tools such as gene transformation and gene silencing offer new opportunities for examining the genetic basis of P. sojae biology, physiology, and pathogenicity (24). To better understand G protein signaling mechanisms that govern zoospore development and behavior in P. sojae, we characterized one of the putative GPCRs, PsGPR11, which is highly expressed in zoospores and induced upon early infection. Then we evaluated the role of PsGPR11 in asexual development, chemotaxis to the isoflavone daidzein, and soybean virulence by means of stable transformation-mediated gene silencing approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

P. sojae strains and culture conditions.

P. sojae strain P6497 and all transgenic lines in this study were routinely grown on 10% V8 medium at 25°C in the dark as described by Erwin and Ribiero (12). We collected the asexual samples such as vegetative hyphae, sporulating hyphae, zoospores, cyst, and germinated cysts as described by Hua et al. (18); immediately froze them in liquid N2; and then ground them for RNA extraction.

DNA and RNA manipulation of P. sojae.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) of P. sojae strain P6497 and the putative transformants was isolated from hyphae grown in 10% V8 liquid medium following the partially modified protocol described by Tyler et al. (45).

Total RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA II RNA extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the procedures described by the manufacturer.

To clone PsGPR11, gDNA of mycelia and cDNA of zoospores from the P. sojae strain P6497 were used as templates in PCRs with the primers PsGPR11F1 (5′-ATGGAGTTCTGGCCGCTGGGAG-3′) and PsGPR11R1 (5′-CTACAACTTCCAACCGCGCGAC-3′) The PCR was performed with 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 90 s at 72°C. The PCR products were cloned in pMD18-T vectors and sequenced.

To investigate the expression level and silencing efficiency of PsGPR11 and some downstream candidates which were identified by Hua et al. (18), semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by the following steps: first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (2 μg) using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (RNase-free; Invitrogen) and oligo(dT)18 primer (Invitrogen) in a 20-μl reaction mixture; the PCR material for PsGPR11 was amplified from the cDNA templates (1 μl) with the primers PsGPR11F2 and PsGPR11R2 under the following conditions: 94°C for 1 min followed by 33 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. The P. sojae Act (actin A) gene was used as reference, and PCR conditions were 94°C for 1 min followed by 24 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 59°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min with the primers ActF and ActR, using the same templates as those for PsGPR11. The complete removal of all DNA was validated in a PCR under the same conditions as those used for the RT-PCR, except that the cDNA synthesis step at 37°C was omitted. The primers used in the reactions are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All RT-PCRs were performed at least three times.

Sequence analysis.

The transmembrane domain was predicted on DAS (http://www.sbc.su.se/%7Emiklos/DAS/) (9), Conpred II (http://bioinfo.si.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/∼ConPred2/) (1), and TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) (8). The orthologs of PsGPR11 in P. ramorum and Phytophthora capsici (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/) and P. infestans (http://www.broad.mit.edu/) were identified using the TBALST algorithm. The multiple alignments were performed using EBI Clustal W2 and default parameters.

Plasmid construction and P. sojae transformation.

The full-length open reading frame (ORF) of PsGPR11 was amplified with PrimeStar polymerase (TaKaRa) from PsGPR11-pMD18. This fragment was ligated in antisense orientation into the pHAM34 vector digested by SmaI and sequenced to confirm the accuracy of the whole open reading frame. This resulted in the plasmid pGPR11.

We transformed P. sojae by a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transformation strategy (11, 18, 34) with a 1:3 combination of the selection plasmid pHspNpt consisting of the hsp70 promoter of Bremia lactucae fused to the nptII coding sequence and the ham34 terminator of B. lactucae (19) and the target plasmids, including the antisense construct of PsGPR11.

Putative PsGPR11-silenced transformants were screened by the following steps. First, genomic PCR screening of all transformants and wild-type (WT) strains was performed with oligonucleotides HMF (5′-TTCTCCTTTTCACTCTCACG-3′) and HMR (5′-AGACACAAAATCTGCAACTTC-3′). Next, RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from each line using oligonucleotides PsGPR11F2 and PsGPR11R2 to evaluate the efficiency of silencing.

Analysis of zoospore behavior and chemotaxis.

To analyze the germination of zoospores, tubes containing a 300-μl zoospore suspension were vortexed for 90 s to induce encystment. Germination was measured by strongly shaking the tubes followed by transferring drops of cyst suspension to glass plates and incubating them in 5% V8 liquid with 90% humidity at 25°C for 2, 4, or 6 h. At least 100 cysts were examined for each treatment, and all treatments were replicated three times. To access zoospore encystment, equal volumes (50 μl) of zoospore suspension were pipetted onto glass plates and incubated at 25°C with 90% humidity. After 2 h, the number of encysted zoospores was counted under a microscope.

Chemotaxis assays were performed according to the methods of Hua et al. (18) by dropping a zoospore suspension with 0.5 μl agarose containing 30 μM daidzein (an isoflavone) or 25 μM glutamic acid.

To observe the sporangial development, P. sojae strain P6497 and the PsGPR11-silenced transformant hyphal plugs were inoculated in 20 ml sterile clarified 10% V8 juice in 90-mm petri dishes. After 3 days of stationary culture, sporangia were prepared by repeatedly washing 3-day-old hyphae incubated in 10% V8 broth with sterile distilled water (SDW) and incubating the hyphae in the dark at 25°C for 8 h until sporangia developed on most of the hyphae; then the plates were incubated at 15°C for 0.5 h followed by transfer to 25°C for at least 2 h to allow release of zoospores.

Virulence assay.

For infection assays, detached soybean leaves of Williams, a cultivar that is susceptible to P. sojae strain P6497, were placed in petri dishes. Each leaflet was inoculated on the abaxial side with a 5-mm hyphal plug or with a 30-μl droplet of zoospore suspension containing 1,000 zoospores. The leaves were incubated in a climate room at 25°C under 90% humidity. Pictures of the lesions were taken at 3 and 6 days postinoculation (dpi). Leaves inoculated for 2, 4, or 12 h were soaked in 0.5% Coomassie brilliant blue for 2 min, destained with alcohol, and washed with SDW three to five times. The infected leaves were examined under a microscope.

Protein-protein interaction assays using the yeast two-hybrid assay.

Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were performed as described previously (38). cDNAs of the PsGPR11 second and third cytoplasmic loops and C-terminal cytoplasmic tail were cloned into the bait vector pGBKT7 and the prey vector, respectively. The full-length PsGPA1 cDNA was cloned into plasmid pGADT7. All inserted cDNA sequences were confirmed by sequencing. Both bait constructs and prey constructs were cotransformed into yeast strain AH109 and grown on Leu− Trp− medium containing 2% agar at 30°C for 4 to 5 days. The clones were further grown on Leu− Trp− Ade− His− medium containing 2% agar at 30°C for 3 to 4 days to test interaction. Positive interactions were further confirmed by β-galactosidase enzyme activity assays as described by the protocol.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of PsGPR11 has been submitted to the NCBI (accession number FJ349606).

RESULTS

PsGPR11 encodes a typical seven-transmembrane-spanning protein.

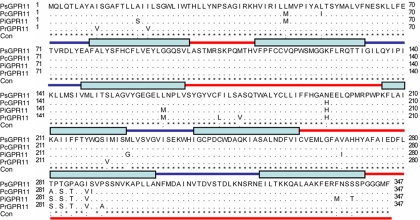

Twenty-four GPR genes have been bioinformatically identified and analyzed in P. sojae (4). Based on our unpublished P. sojae transcriptional landscape defined by RNA sequencing approaches, we found that PsGPR11 was the only member in the GPCR family that was highly upregulated in zoospores and cysts. Further reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis revealed that the PsGPR11 open reading frame contained 1,044 nucleotides without an intron, resulting in a protein with 347 amino acids (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Seven possible transmembrane regions were predicted for a plasma membrane protein by using hydrophobicity algorithms from the Conpred II, DAS, and TMHMM software programs (data not shown). These structural features suggested that PsGPR11 was a candidate GPCR. There were no characterized homologous hits for PsGPR11 when it was BLASTed in the NCBI database, suggesting that it does not share sequence similarity with known GPCRs. The PsGPR11 orthologs were identified from P. ramorum, P. infestans, and P. capsici and were named PrGPR11, PiGPR11, and PcGPR11, respectively. They were highly conserved through multiple alignments (Fig. 1). These data strongly suggested that the GPR11s were present and had already diverged from one another in a common ancestor of the Phytophthora lineage.

Fig. 1.

PsGPR11 encodes a protein containing seven transmembrane domains. Multiple alignments of PsGPR11 and its orthologs from sequenced Phytophthora strains were made by Clustal X. The stars, periods, and colons indicate sequences that are identical, highly similar, and only slightly similar, respectively. Blue lines, extracellular regions; blue boxes, TM domains; red lines, intracellular regions.

PsGPR11 is differentially expressed in the asexual life cycle and during infection.

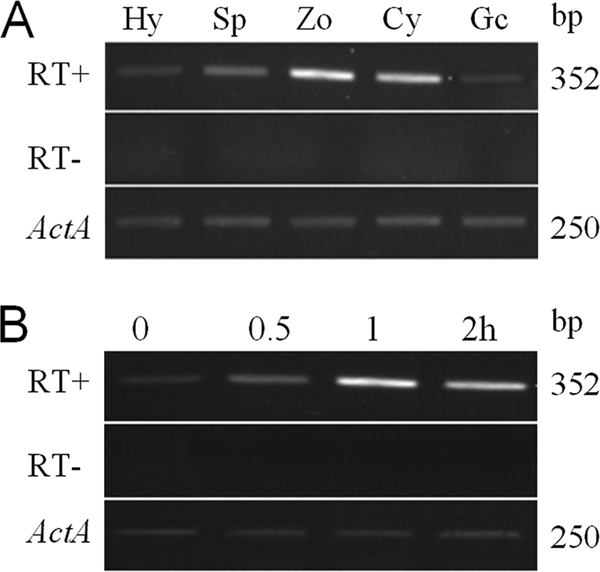

To determine the expression patterns of PsGPR11, we employed semiquantitative RT-PCR to analyze mRNA accumulation in distinct developmental stages including vegetative hyphae, sporulating hyphae, zoospores, cysts, and germinated cysts and during infection. The highest expression level was found in zoospores; other P. sojae asexual life stages all contained PsGPR11 mRNA, but at a much lower level in vegetative hyphae and germinated cysts (Fig. 2A). This result was identical to the expression profiling defined by the RNA-Seq technology. PsGPR11 mRNA was also detectable in various stages of infected leaves at up to 2 h postinoculation, although the highest level was found at 1 h postinoculation (Fig. 2B). These results showed that PsGPR11 has differential expression patterns during the asexual life cycle and early infection (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Expression analysis of PsGPR11 during life cycle of and infection by P. sojae. (A) Expression of PsGPR11 during asexual development of P. sojae. Using RT-PCR, we detected PsGPR11 expression from vegetative hyphae (Hy), sporulating hyphae (Sp), zoospores (Zo), cysts (Cy), and germinating cysts (Gc). (B) Expression of PsGPR11 during infection of soybean leaves. Mycelium was inoculated on leaves of soybean cultivar Williams during the indicated time course, i.e., 0.5, 1.0, and 2 h postinoculation. In both panel A and panel B, the top panel (RT+) shows amplification with inner primers of PsGPR11 at 30 cycles (RT− indicates the control reactions when reverse transcriptase was omitted to exclude the possibility of DNA contamination), and the bottom panel indicates the amplifications of the P. sojae actin (Act) gene. RT-PCR products were visualized on ethidium bromide-stained gels, and the sizes are indicated on the right.

Silencing of PsGPR11 gene expression in P. sojae.

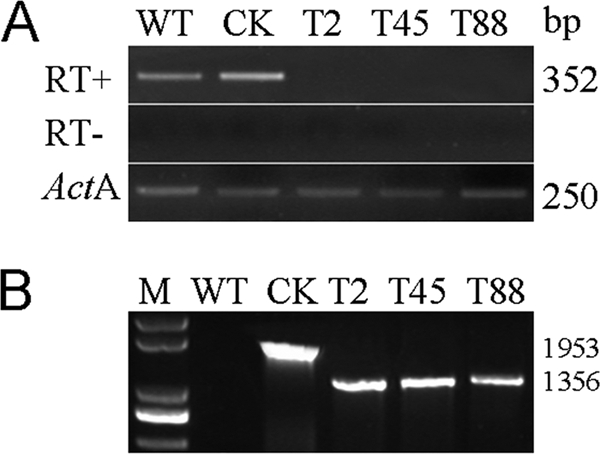

To obtain transformants that lack PsGPR11 expression, we used a gene silencing strategy based on the PEG-mediated protoplast stable transformation of P. sojae. Based on our recently reported P. sojae transformation and gene silencing methods (11, 18, 50), we cotransformed the construct containing the PsGPR11 coding region in the antisense orientation, which is driven by the constitutive pHam34 promoter with pTH209, which was used as a selection marker carrying Geneticin (19). To select the PsGPR11-silenced transformants, we initially screened 110 putative transformants that could grow on a selection medium containing 50 μg/ml Geneticin (Shanghai Sangon BS723); we screened these putative transformants using genomic PCR with the HMF and HMR primers (see Materials and Methods). Initially, 80 PsGPR11-integrated transformants were obtained (data not shown) because transformants that successfully transformed exogenous PsGPR11 or the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene produced expected products; in contrast, the wild-type strain and transformants that did not contain exogenous PsGPR11 failed to produce the expected products. PsGPR11-integrated transformants were further evaluated for PsGPR11 mRNA accumulation level using semiquantitative RT-PCR. Of 80 candidate transformants, only 3 (T2, T45, and T88) failed to produce the given amplicons when the normal number of PCR cycles was applied with zoospore RNA as the initial template (Fig. 3A). Genomic PCR analysis also revealed that pGPR11 was introduced in T2, T45, and T88 (Fig. 3B). These results showed that PsGPR11 expression in the three transformants T2, T45, and T88 was silenced by stable P. sojae transformation.

Fig. 3.

Generation of PsGPR11-silenced mutants. (A) RT-PCR estimation of PsGPR11 gene expression level using vegetative hyphal RNA from wild type and the indicated transformants. RT-PCRs included either primers of PsGPR11 under the normal RT-PCR conditions with (RT+) or without (RT−) reverse transcriptase or primers for actin A (ActA). The PCR product sizes are shown at the right. (B) Genomic PCR screenings were performed using gDNA as template on indicated strains with the combinations of primers HamF and HamR. M, 200-bp marker. WT, wild type P6497; CK, GUS-expressing transformant, used as a positive control; T2, T45, and T88, PsGPR11-silenced transformants. The PCR product sizes are shown at the right.

PsGPR11-silenced transformants show aberrant sporangial development and zoospore behavior.

Phenotypes of the three silenced transformants were compared with that of the WT strain P6497, and a GUS-expressing transformant (CK) throughout its life cycle. Overall, the PsGPR11-silenced transformants (T2, T45, and T88) showed no difference in growth rate or colony morphology compared to WT and CK. No obvious differences were observed between the silenced transformants and WT and CK in the morphological size of hyphae or sporangia or in sporangium production (Table 1 ), suggesting that vegetative development can proceed in the absence of PsGPR11. It has been reported that pheromone sensing is mediated by the GPCR signaling pathway in fungi, and so the PsGPR11-silenced mutants, WT, and CK were cultured on 10% V8 for 10 days, and oospore production was examined microscopically. The results showed that oospores formed normally in the PsGPR11-silenced transformants, WT, and CK (Table 1), which implied that sexual development was not impaired.

Table 1.

Phenotypic characterization of PsGPR11-silenced transformantse

| Characteristic | WT | CK | T2 | T45 | T88 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyphal growtha | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.08 |

| Encystment ratiob | 10.2 A | 9.6 A | 81.3 B | 82.0 B | 80.5 B |

| Cyst germinationc | 48.87 A | 48.22 A | 14.00 B | 14.76 B | 16.19 B |

| Oospore productiond | 42 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 42 |

Based on 5 days of growth on 10% V8 medium.

The swimming zoospores were incubated on glass plates at 25°C for 1 h. Numbers of swimming zoospores and encysted zoospores were counted under the microscope, and the ratio of encysted zoospores to the total number of zoospores (swimming and encysted) was calculated.

Percentage of germinated cysts based on counting a minimum of 100 zoospores from each strain.

Oospore production was determined on 10% V8 medium.

WT, wild-type strain P6497; CK, GUS-expressing transformant; T2, T45, and T88, PsGPR11-silenced transformants. Values represent means ± standard deviations, which were calculated in at least three replicates. Values in the same row followed by different uppercase letters are significantly different at P < 0.01.

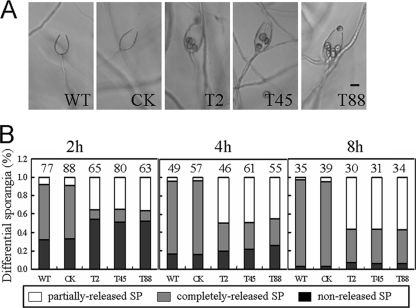

We induced sporangia of WT, CK, and the three PsGPR11-silenced transformants (T2, T45, and T88) to release zoospores by incubating them at 15°C for 30 min followed by a transfer to 25°C. After 2 h, zoospores had completely escaped from about 60% of the WT and CK sporangia (Fig. 4). In contrast, the release of zoospores from sporangia of the PsGPR11-silenced transformants was less efficient. On average, 2 h after induction of zoospore release, only 11% of the sporangia from the transformants could release the zoospores completely while a majority of the control could; about 35% retained one to five zoospores that failed to escape, and the rest of the sporangia did not release zoospores at all; however, the retained zoospores did not show any obvious alterations, and the morphology of the sporangia was normal (data not shown). After 8 h, more than 50% failed to completely release their zoospores, compared to 4% of WT and CK sporangia that did so (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that the silencing of PsGPR11 affected the efficiency of zoospore release.

Fig. 4.

Aberrant sporangial development of PsGPR11-silenced transformants. (A) Sporangia from wild-type strain P6497 (WT), the GUS-expressing transformant (CK), and three silenced transformants (T2, T45, and T88) were treated by cold shock (15°C) for 30 min and then inoculated at room temperature (25°C) for 4 h. Pictures were taken under a microscope. Bar, 20 μm. (B) Percentages of differential sporangia after cold shock followed by incubation at 25°C for 2, 4, and 8 h. Gray bars, nonreleased sporangia; black bars, completely released sporangia; white bars, partially released sporangia. The total number of sporangia is indicated above each column.

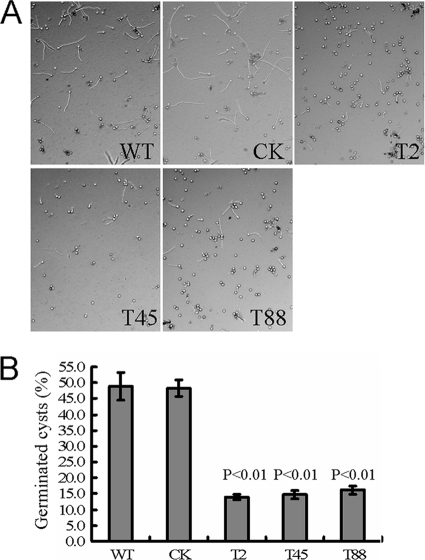

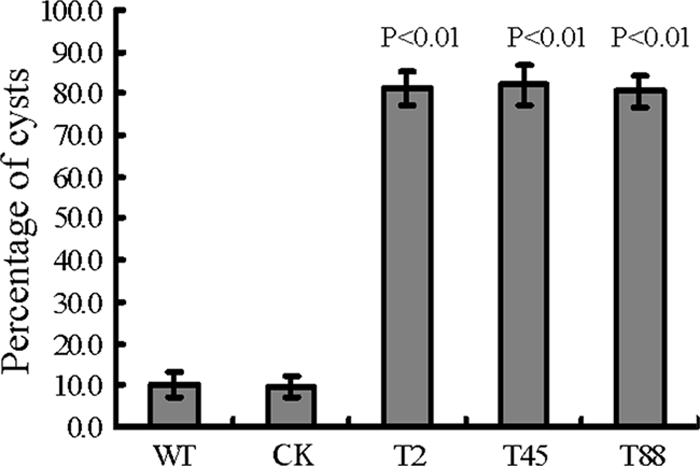

Zoospore behavior was also markedly affected in the PsGPR11-silenced transformants. One of the most striking differences was the time span between zoospore release and encystment. About 80.5 to 82% of the zoospores from the three PsGPR11-silenced transformants (T2, T45, and T88) were encysted within an hour after release from the sporangia, whereas the majority of the WT and CK zoospores swam vigorously and continued swimming for hours before they encysted (Fig. 5). As in other eukaryotes, chemotactic reception is mediated by GPCRs (7). We tested whether the chemotactic response to isoflavones, which are released by soybean roots, was affected in the zoospores of the PsGPR11-silenced transformants. We found that zoospore chemotaxis under various concentrations of the isoflavone daidzein was not impaired in the silenced transformants (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 5.

Zoospore encystment rates. Swimming zoospores from wild-type strain P6497 (WT), the GUS-expressing transformant (CK), and three PsGPR11-silenced mutants (T2, T45, and T88) were incubated on glass plates at 25°C for 1 h. The numbers of swimming zoospores and encysted zoospores were counted under the microscope, and the ratio of encysted zoospores to the total zoospores (swimming and encysted) was calculated.

Under optimal conditions, zoospores start to germinate to produce hyphae after the encystment stage. The zoospore germination rate of the PsGPR11-silenced mutants was dramatically reduced. Zoospore suspensions of WT, CK, and the three PsGPR11-silenced mutants were strongly vortexed to stimulate rapid physical encystment, and the cysts were incubated at 25°C. After 2 h, only about 14 to 16% of the cysts from the silenced strains (T2, T45, and T88) germinated to produce germ tubes, whereas almost 50% of the cysts obtained from the WT strain germinated (Fig. 6). These results indicated that zoospore behavior, including the time span between zoospore release and encystment and germination of PsGPR11-silenced transformants, was altered.

Fig. 6.

Cyst germination of PsGPR11-silenced mutants was reduced. (A) Zoospores from wild-type strain P6497 (WT), a GUS-expressing transformant (CK), and three PsGPR11-silenced mutants (T2, T45, and T88) were encysted by being vortexed for 90 s, and cysts were incubated in clarified 5% V8 liquid medium at 25°C. Microscopic pictures were taken 2 h after inoculation. (B) The numbers of germinated cysts and nongerminated cysts were counted under the microscope at 2 h. The ratio of germinated cysts to the total cysts (germinated and nongerminated) was calculated. Statistics were based on a two-tailed t test. Significant differences were at a level of P < 0.01.

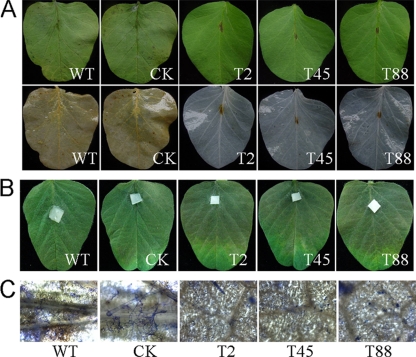

The virulence of PsGPR11-silenced transformant zoospores is severely impaired.

To determine the effect of PsGPR11 deficiency on virulence, we used a zoospore suspension with the same number of effective zoospores preserving germination ability according to cyst germination ratio at 2 h to spot-inoculate leaves from the soybean cultivar Williams, which is susceptible to WT. At 3 days dpi there were no disease symptoms on Williams leaflets, and at 6 dpi there was a very small necrosis-like lesion at the inoculation site (Fig. 7A). In contrast, leaves inoculated with WT and CK zoospores showed typical disease symptoms at 3 dpi, and at 6 dpi the water-soaked lesion had spread through the whole leaf (Fig. 7B). Leaves were inoculated with hyphal plugs instead of zoospores to investigate whether the aberrant behavior of the PsGPR11-silenced transformant zoospores was the cause of the pathogenicity loss. The results showed no obvious difference in the spread of disease symptoms; the PsGPR11-silenced transformants were as virulent as WT and CK (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting that virulence itself was not impaired but, more likely, that preinfection events of zoospores were disturbed in PsGPR11-silenced transformants.

Fig. 7.

Virulence assay for PsGPR11-silenced mutants. (A) Leaflets of 10-day-old soybean plants (cultivar Williams) were inoculated with equal numbers of zoospores in suspension (1,000 zoospores) from P6497 (WT), the GUS-expressing transformant (CK), and three silenced mutants (T2, T45, and T88) at 25°C. Top and bottom panels show the same leaves, except that the bottom panels show leaves after destaining in alcohol. (B) Leaves of 10-day-old soybean plants (cultivar Williams) were inoculated with hyphal plugs from P6497 (WT), the GUS-expressing transformant (CK), and three silenced mutants (T2, T45, and T88). Pictures were taken at 6 dpi. (C) Detailed pictures of germinated cysts on soybean leaves that were inoculated with zoospores and incubated at 25°C for 12 h. The leaves were then put into ethanol to destain the chlorophyll and subsequently into 0.5% Coomassie brilliant blue for 2 min. After the leaves were washed in water for 10 min, the pictures were taken.

To test whether the mutant zoospores were simply not able to encyst or to germinate, we analyzed the efficiency of germination after inoculation on soybean leaves. Many of the encysted zoospores of wild-type strain P6497 had germinated at 12 h after inoculation, but zoospores of the mutants either were not encysted or had not germinated (Fig. 7C).

The putative candidate target of PsGPR11.

To assess physical interactions between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1, conventional yeast two-hybrid interaction assays were performed with PsGPR11 and PsGPA1. Because PsGPR11is a membrane-bound protein, we made several truncated PrGPR11 constructs by using gene fragments encoding portions of the receptor located in the cytosol, including the second and third cytoplasmic loops (second, positions 98 to 136; third, positions 190 to 211) and the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (positions 273 to 347). No interaction was observed between any of these fragments of PsGPR11 and PsGPA1 (data not shown).

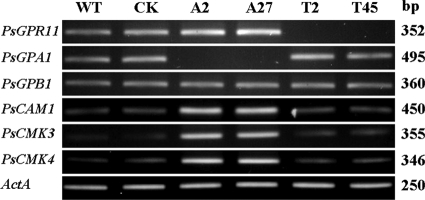

A previous observation by our group revealed that the silencing of the G protein α subunit PsGPA1 expression caused a defect similar to that of PsGPR11-silenced mutants, except for the chemotaxis to the isoflavones (18), suggesting that these two may activate the same downstream pathway. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of genes that were identified as being negatively regulated by PsGPA1, such as PsCAM1, PsCMK3, and PsCMK4, in PsGPR11-silenced mutants. In comparing the expression levels in zoospores of the wild-type strain P6497, the PsGPA1-silenced mutants A2 and A27, and the PsGPR11-silenced mutants T2 and T45, we found that the expression of PsCAM1, PsCMK3, PsCMK4, PsGPA1, and PsGPB1 in the PsGPR11-silenced mutants was similar to that of P6497; however, the expression of PsCAM1, PsCMK3, and PsCMK4 was clearly upregulated in the two PsGPA1-silenced mutants (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Putative downstream targets of PsGPR11. Expression of G proteins and genes encoding putative downstream targets of the Gα subunit in zoospores of the wild-type strain P6497 (WT), the GUS-expressing transformant (CK), the PsGPA1-silenced mutants A2 and A27, and PsGPR11-silenced mutants T2 and T45 is shown. RT-PCR products were visualized on ethidium bromide-stained gels, and their sizes are indicated on the right.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that P. sojae possesses a signaling pathway possibly mediated by PsGPR11 that controls multiple physiological and developmental processes of zoospores and is indispensable for zoospore virulence. Silencing of PsGPR11 severely affects zoospore release from sporangia, time span between zoospore release and encystment, and germination of cysts, as well as zoospore virulence.

PsGPR11 belongs to a GPCR family.

The GPCR family represents the largest and most diverse group of membrane-bound proteins. While GPCRs respond to a vast array of ligands, a typical GPCR contains a conserved structure of seven-transmembrane-spanning (or heptahelical) domains. GPCRs form one of the largest protein families in animal genomes (13, 15, 20). Mining the sequenced Phytophthora genomes revealed that P. sojae harbors a large number of GPCRs (4, 46). In addition, Phytophthora contains novel phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases with a GPCR signature, which are homologous to RpkA in Dictyostelium and play a crucial role in cell density sensing (3). So far, little is known about the mechanism underlying GPCR-mediated signaling in Phytophthora. PsGPR11 is a potential GPCR in P. sojae. Using three different TM topological prediction software programs, we predicted that PsGPR11 would possess a seven-transmembrane domain. Although a BLAST search failed to find a known GPCR, very highly similar homologs were found in sequenced Phytophthora genomes, indicating that PsGPR11 might represent a novel GPCR.

Effects of PsGPR11 deficiency on zoospore development and virulence.

Zoospores play a central role in infection and Phytophthora disease epidemics. Studies have shown that G protein signaling is very important in the zoospore stage. RNA-Seq technology and RT-PCR revealed that the highest PsGPR11 expression level was in the zoospore and cyst developmental stages, which suggests a primary function for PsGPR11 in zoospores. We expected that silencing of the gene would severely affect zoospore developmental processes, including efficiency of zoospore release from sporangia, time span between release and encystment, cyst germination, and zoospore virulence. All of the PsGPR11-silenced mutants had severely affected virulence mediated by zoospores, but not the mycelial plug, which indicates that preinfection events of zoospores might be disturbed in the silenced transformants. More studies will be required to determine with certainty how each of the developmental and physiological defects of the PsGPR11-silenced mutants affects virulence.

The association between PsGPA1 and PsGPR11.

Some phenotypes of PsGPR11-silenced mutants were similar to those of PsGPA1-silenced mutants with quicker encystment and less efficient germination, indicating a convergent function. However, the zoospores of PsGPR11-silenced mutants had no altered chemotaxis to the isoflavone daidzein, which was contrary to our initial expectations. In a conventional yeast two-hybrid assay, no interactions were observed between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1. The same results were reported in other GPCR and G proteins (30, 39, 51). To further explore the potential for interactions between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1, the split-ubiquitin system should be used. However, there exists a possibility that no actual interaction occurred between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1.

In other cellular signaling models, cell surface receptors function as dimers or even multimers (40, 42). It is likely that the association of PsGPR11 with other GPCRs or cell surface receptors contributes to isoflavone chemotaxis, but the receptors for these events are still unknown. At present, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that PsGPR11 associates or interacts with a heterotrimeric G protein, i.e., PsGPA1. Although many seven-transmembrane proteins have been predicted in Phytophthora genomes, Phytophthora has one G protein α subunit (18, 33), indicating that there is a single possibility that the seven-transmembrane protein functions in a PsGPA1-dependent or -independent manner. In our study, from results of the conventional yeast two-hybrid assay and RT-PCR analysis of some putative candidates, it is likely that PsGPR11 may regulate downstream events independently of the G protein. G protein-independent responses mediated by the seven-transmembrane receptor have also been observed. For example, metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) regulated responses in a G protein-independent manner in mammals (6, 17), and several cAMP receptor pathways in Dictyostelium have been identified as being G protein independent (6).

Our study has identified a putative GPCR, PsGPR11, that contains seven transmembrane domains. The PsGPR11-silenced mutants that we generated can be exploited to find downstream effectors of PsGPR11. Demonstrating whether there is a direct interaction between PsGPR11 and PsGPA1 will help researchers understand the signaling pathways of the heterotrimeric G protein in Phytophthora. In addition, elucidating other GPCRs that may or may not depend on G protein function will help identify the network of G protein signaling pathways that underlie the development and pathogenicity of Phytophthora pathogens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National “973” Project (2009CB119202), the NSFC project (30671345), and the Natural Sciences Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK2007161) to Yuanchao Wang.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 11 December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai M., Mitsuke H., Ikeda M., Xia J. X., Kikuchi T., Satake M., Shimizu T. 2004. ConPred II: a consensus prediction method for obtaining transmembrane topology models with high reliability. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W390–W393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahn Y. S., Xue C., Idnurm A., Rutherford J. C., Heitman J., Cardenas M. E. 2007. Sensing the environment: lessons from fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:57–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakthavatsalam D., Brazill D., Gomer R. H., Eichinger L., Rivero F., Noegel A. A. 2007. A G protein-coupled receptor with a lipid kinase domain is involved in cell-density sensing. Curr. Biol. 17:892–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakthavatsalam D., Meijer H. J., Noegel A. A., Govers F. 2006. Novel phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases with a G-protein coupled receptor signature are shared by Dictyostelium and Phytophthora. Trends Microbiol. 14:378–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolker M. 1998. Sex and crime: heterotrimeric G proteins in fungal mating and pathogenesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 25:143–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brzostowski J. A., Kimmel A. R. 2001. Signaling at zero G: G-protein-independent functions for 7-TM receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterina M. J., Devreotes P. N. 1991. Molecular insights into eukaryotic chemotaxis. FASEB J. 5:3078–3085 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Yu P., Luo J., Jiang Y. 2003. Secreted protein prediction system combining CJ-SPHMM, TMHMM, and PSORT. Mamm. Genome 14:859–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cserzo M., Wallin E., Simon I., von Heijne G., Elofsson A. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeZwaan T. M., Carroll A. M., Valent B., Sweigard J. A. 1999. Magnaporthe grisea Pth11p is a novel plasma membrane protein that mediates appressorium differentiation in response to inductive substrate cues. Plant Cell 11:2013–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dou D., Kale S. D., Wang X., Chen Y., Wang Q., Jiang R. H., Arredondo F. D., Anderson R. G., Thakur P. B., McDowell J. M., Wang Y., Tyler B. M. 2008. Conserved C-terminal motifs required for avirulence and suppression of cell death by Phytophthora sojae effector Avr1b. Plant Cell 20:1118–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erwin D. C., Ribiero O. K. 1996. Phytophthora diseases worldwide. APS Press, St. Paul, MN [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredriksson R., Schioth H. B. 2005. The repertoire of G-protein-coupled receptors in fully sequenced genomes. Mol. Pharmacol. 67:1414–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galagan J. E., Calvo S. E., Borkovich K. A., Selker E. U., Read N. D., Jaffe D., FitzHugh W., Ma L.-J., Smirnov S., Purcell S., Rehman B., Elkins T., Engels R., Wang S., Nielsen C. B., Butler J., Endrizzi M., Qui D., Ianakiev P., Bell-Pedersen D., Nelson M. A., Werner-Washburne M., Selitrennikoff C. P., Kinsey J. A., Braun E. L., Zelter A., Schulte U., Kothe G. O., Jedd G., Mewes W., Staben C., Marcotte E., Greenberg D., Roy A., Foley K., Naylor J., Stange-Thomann N., Barrett R., Gnerre S., Kamal M., Kamvysselis M., Mauceli E., Bielke C., Rudd S., Frishman D., Krystofova S., Rasmussen C., Metzenberg R. L., Perkins D. D., Kroken S., Cogoni C., Macino G., Catcheside D., Li W., Pratt R. J., Osmani S. A., DeSouza C. P. C., Glass L., Orbach M. J., Berglund J. A., Voelker R., Yarden O., Plamann M., Seiler S., Dunlap J., Radford A., Aramayo R., Natvig D. O., Alex L. A., Mannhaupt G., Ebbole D. J., Freitag M., Paulsen I., Sachs M. S., Lander E. S., Nusbaum C., Birren B. 2003. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422:859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gloriam D. E., Fredriksson R., Schioth H. B. 2007. The G protein-coupled receptor subset of the rat genome. BMC Genomics 8:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han K. H., Seo J. A., Yu J. H. 2004. A putative G protein-coupled receptor negatively controls sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1333–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heuss C., Gerber U. 2000. G-protein-independent signaling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 23:469–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua C., Wang Y., Zheng X., Dou D., Zhang Z., Govers F., Wang Y. 2008. A Phytophthora sojae G-protein α subunit is involved in chemotaxis to soybean isoflavones. Eukaryot. Cell 7:2133–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Judelson H. S., Tyler B. M., Michelmore R. W. 1991. Transformation of the oomycete pathogen, Phytophthora infestans. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 4:602–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamesh N., Aradhyam G. K., Manoj N. 2008. The repertoire of G protein-coupled receptors in the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostenis E. 2004. A glance at G-protein-coupled receptors for lipid mediators: a growing receptor family with remarkably diverse ligands. Pharmacol. Ther. 102:243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krystofova S., Borkovich K. A. 2006. The predicted G-protein-coupled receptor GPR-1 is required for female sexual development in the multicellular fungus Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1503–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni R. D., Thon M. R., Pan H., Dean R. A. 2005. Novel G-protein-coupled receptor-like proteins in the plant pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genome Biol. 6:R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamour K. H., Win J., Kamoun S. 2007. Oomycete genomics: new insights and future directions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latijnhouwers M., Govers F. 2003. A Phytophthora infestans G-protein beta subunit is involved in sporangium formation. Eukaryot. Cell 2:971–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latijnhouwers M., Ligterink W., Vleeshouwers V. G., van West P., Govers F. 2004. A Galpha subunit controls zoospore motility and virulence in the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Mol. Microbiol. 51:925–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lengeler K. B., Davidson R. C., D'Souza C., Harashima T., Shen W. C., Wang P., Pan X., Waugh M., Heitman J. 2000. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:746–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L., Borkovich K. A. 2006. GPR-4 is a predicted G-protein-coupled receptor required for carbon source-dependent asexual growth and development in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1287–1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L., Wright S. J., Krystofova S., Park G., Borkovich K. A. 2007. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling in filamentous fungi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:423–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X., Yue Y., Li B., Nie Y., Li W., Wu W. H., Ma L. 2007. A G protein-coupled receptor is a plasma membrane receptor for the plant hormone abscisic acid. Science 315:1712–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loftus B. J., Fung E., Roncaglia P., Rowley D., Amedeo P., Bruno D., Vamathevan J., Miranda M., Anderson I. J., Fraser J. A., Allen J. E., Bosdet I. E., Brent M. R., Chiu R., Doering T. L., Donlin M. J., D'Souza C. A., Fox D. S., Grinberg V., Fu J., Fukushima M., Haas B. J., Huang J. C., Janbon G., Jones S. J., Koo H. L., Krzywinski M. I., Kwon-Chung J. K., Lengeler K. B., Maiti R., Marra M. A., Marra R. E., Mathewson C. A., Mitchell T. G., Pertea M., Riggs F. R., Salzberg S. L., Schein J. E., Shvartsbeyn A., Shin H., Shumway M., Specht C. A., Suh B. B., Tenney A., Utterback T. R., Wickes B. L., Wortman J. R., Wye N. H., Kronstad J. W., Lodge J. K., Heitman J., Davis R. W., Fraser C. M., Hyman R. W. 2005. The genome of the basidiomycetous yeast and human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Science 307:1321–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maidan M. M., De Rop L., Serneels J., Exler S., Rupp S., Tournu H., Thevelein J. M., Van Dijck P. 2005. The G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 and the Galpha protein Gpa2 act through the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway to induce morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:1971–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maria Laxalt A., Latijnhouwers M., van Hulten M., Govers F. 2002. Differential expression of G protein alpha and beta subunit genes during development of Phytophthora infestans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 36:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLeod A., Fry B. A., Zuluaga A. P., Myers K. L., Fry W. E. 2008. Toward improvements of oomycete transformation protocols. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 55:103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miwa T., Takagi Y., Shinozaki M., Yun C. W., Schell W. A., Perfect J. R., Kumagai H., Tamaki H. 2004. Gpr1, a putative G-protein-coupled receptor, regulates morphogenesis and hypha formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:919–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neves S. R., Ram P. T., Iyengar R. 2002. G protein pathways. Science 296:1636–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oldham W. M., Hamm H. E. 2008. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:60–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osman A. 2004. Yeast two-hybrid assay for studying protein-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 270:403–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandey S., Assmann S. M. 2004. The Arabidopsis putative G protein-coupled receptor GCR1 interacts with the G protein alpha subunit GPA1 and regulates abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 16:1616–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. 2002. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzo D. M., Garbelotto M., Hansen E. M. 2005. Phytophthora ramorum: integrative research and management of an emerging pathogen in California and Oregon forests. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43:309–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulte G., Levy F. O. 2007. Novel aspects of G-protein-coupled receptor signalling—different ways to achieve specificity. Acta Physiol. (Oxford) 190:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seo J. A., Han K. H., Yu J. H. 2004. The gprA and gprB genes encode putative G protein-coupled receptors required for self-fertilization in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1611–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyler B. M. 2007. Phytophthora sojae: root rot pathogen of soybean and model oomycete. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyler B. M., Forster H., Coffey M. D. 1995. Inheritance of avirulence factors and restriction fragment length polymorphism markers in outcrosses of the oomycete Phytophthora sojae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 8:515–523 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyler B. M., Tripathy S., Zhang X., Dehal P., Jiang R. H., Aerts A., Arredondo F. D., Baxter L., Bensasson D., Beynon J. L., Chapman J., Damasceno C. M., Dorrance A. E., Dou D., Dickerman A. W., Dubchak I. L., Garbelotto M., Gijzen M., Gordon S. G., Govers F., Grunwald N. J., Huang W., Ivors K. L., Jones R. W., Kamoun S., Krampis K., Lamour K. H., Lee M. K., McDonald W. H., Medina M., Meijer H. J., Nordberg E. K., Maclean D. J., Ospina-Giraldo M. D., Morris P. F., Phuntumart V., Putnam N. H., Rash S., Rose J. K., Sakihama Y., Salamov A. A., Savidor A., Scheuring C. F., Smith B. M., Sobral B. W., Terry A., Torto-Alalibo T. A., Win J., Xu Z., Zhang H., Grigoriev I. V., Rokhsar D. S., Boore J. L. 2006. Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science 313:1261–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tyler B. M., Wu M., Wang J., Cheung W., Morris P. F. 1996. Chemotactic preferences and strain variation in the response of Phytophthora sojae zoospores to host isoflavones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2811–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van West P., Appiah A. A., Gow N. A. R. 2003. Advances in research on oomycete root pathogens. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 62:99–113 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Versele M., Lemaire K., Thevelein J. M. 2001. Sex and sugar in yeast: two distinct GPCR systems. EMBO Rep. 2:574–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Dou D., Wang X., Li A., Sheng Y., Hua C., Cheng B., Chen X., Zheng X., Wang Y. 2009. The PsCZF1 gene encoding a C2H2 zinc finger protein is required for growth, development and pathogenesis in Phytophthora sojae. Microb. Pathog. 47:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xue C., Bahn Y. S., Cox G. M., Heitman J. 2006. G protein-coupled receptor Gpr4 senses amino acids and activates the cAMP-PKA pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:667–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xue C., Hsueh Y. P., Heitman J. 2008. Magnificent seven: roles of G protein-coupled receptors in extracellular sensing in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:1010–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.