Abstract

Objective

Human parturition is characterized by the activation of genes involved in acute inflammatory in the fetal membranes. Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is a mitochondrial enzyme that scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS). MnSOD is up-regulated in sites of inflammation and has an important role in the down-regulation of acute inflammatory processes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the differences in MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes in patients with term and preterm labor as well as in acute chorioamnionitis.

Study design

Fetal membranes were obtained from patients in the following groups: 1) term not in labor (n=29); 2) term in labor (n=29); 3) spontaneous preterm labor with intact mebranes (n=16); 4) PTL with histological chorioamnionitis (n=12); 5) preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM; n=17); and 6) PPROM with histological chorioamnionitis (n=21). MnSOD mRNA expression in the membranes was determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Results

1) MnSOD mRNA expression was higher in the fetal membranes of patients at term in labor than those not in labor (2.4-fold; p=0.02); 2) the amount of MnSOD mRNA in the fetal membranes was higher in PTL than in term labor or in PPROM (7.2-fold, p=0.03; 3.2-fold, p=0.03, respectively); 3) MnSOD mRNA expression was higher when histological chorioamnionitis was present both among patients with PPROM (3.8-fold, p=0.02) and with PTL (5.4-fold, p=0.02) than in patients with these conditions without histological chorioamnionitis; 4) expression of MnSOD mRNA was higher in PTL with chorioamnionitis than in PPROM with chorioamnionitis (4.3-fold, p=0.03);

Conclusion

The increase in MnSOD mRNA expression by fetal membranes in term labor and in histological chorioamnionitis in PTL and PPROM suggests that the fetus deploys anti-oxidant mechanisms to constrain the inflammatory processes in the chorioamniotic membranes.

Keywords: fetal gender, gene expression, preterm delivery, preterm labor, preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes, reactive oxygen species, scavenger

INTRODUCTION

Human parturition involves a “common pathway” that is activated by physiological signals in term labor and by pathological processes in preterm labor[1]. This common pathway is clinically manifested in the increased contractility of the myometrium, the ripening and remodeling of the cervix and the activation of the maternal decidua and the chorioamniotic membranes[1–3]. The chorioamniotic membranes undergo complex morphological and biochemical changes[4] that are associated with the activation of genes involved in acute inflammatory responses[5–7]. Indeed, our group has reported microarray experiments which have revealed that human term labor is characterized by an acute inflammation gene expression signature in the fetal membranes in the absence of evidence of clinical and histological chorioamnionitis[8].

In addition to a pro-inflammatory response in the chorioamniotic membranes, our microarray experiments also revealed that labor at term is associated with the 2.6-fold up-regulation of SOD2, which encodes MnSOD[8]. These results were consistent with a prior microarray experiment performed by our group, in which we found differential expression of SOD2 in the fetal membranes in spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes (PTL) when compared to preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes (PPROM)[9]. Moreover, this gene was differentially up-regulated in the fetal membranes of patients with histological chorioamnionitis[9].

MnSOD is a member of an evolutionarily conserved iron/manganese superoxide dismutase family, which localizes to the mitochondria and scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by oxidative phosphorylation[10–13]. ROS represent a double edged sword; in low concentrations, they participate in physiological intracellular signaling pathways and defense mechanisms against infections[14–16]. However, in higher concentrations, ROS may lead to enhanced oxidative stress and play an important role in aging and the pathophysiology of various diseases, such as atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia or preterm labor[16–44]. In addition, ROS activate NF-κB and enhance the subsequent expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which leads to the orchestration of the inflammatory pathway[39,45] and the propogation of parturition[46]. Inflammatory processes then may lead to the increased generation of ROS and oxidative stress[47]. On the contrary, inflammatory processes up-regulate MnSOD that in turn down-regulates inflammation and oxidative stress by suppressing NF-κB, AP-1 and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. Thus, MnSOD has been proposed to have an important function in protection against cell injury mediated by inflammation and oxidative stress[48–52]. Remarkably, MnSOD has been implicated as a longevity-associated gene, which has a higher expression in females than in males [28,43,53].

Based on our previous microarray experiments[8,9], SOD2 seems to be involved in the processes leading to term and preterm parturition in the fetal membranes. In order to confirm these microarray results and to reveal the differences in SOD2 expression in the chorioamniotic membranes between term and preterm parturition and with acute inflammation, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR on samples taken from normal pregnant women at term with or without labor and from patients presenting with PTL or PPROM, with or without histological signs of chorioamnionitis. Indeed, our study confirmed increased MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes in term and preterm parturition, and chorioamnionitis. Furthermore, we report gender differences in the differential expression of MnSOD in chorioamnionitis that may influence the redox balance and the inflammatory processes in the fetal membranes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was designed to examine the differential expression of SOD2 in the fetal membranes of patients in the following groups: 1) term not in labor (n=29); 2) term in labor (n=29); 3) PTL (n=16); 4) PTL with histological chorioamnionitis (n=12); 5) PPROM (n=17); and 6) PPROM with histological chorioamnionitis (n=21). Patients presenting with medical complications, multiple pregnancies, fetal congenital or chromosomal abnormalities were excluded. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the collection of samples. The collection and utilization of samples for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH/DHHS) and Wayne State University. Many of these samples have been employed to study the biology of inflammation and labor in both normal pregnant women, and those with complicated pregnancies.

Definitions

Pregnancies were considered normal when there was no evidence of medical, obstetrical or surgical complications, resulting in a term delivery (≥37 gestational weeks) of a healthy neonate whose birth-weight was above the 10th percentile for gestational age[54]. Normal pregnant women in the term not in labor group underwent elective Cesarean section. Labor was defined as the presence of regular uterine contractions that occurred at a frequency of at least 2 in every 10 minutes associated with cervical changes which led to either preterm (<37 weeks of gestation) or term (≥37 weeks of gestation) delivery. Preterm PROM was diagnosed < 37 weeks of gestation in the presence of vaginal pooling and a positive nitrazine or ferning test documented by a sterile speculum examination at admission[55]. Trans-abdominal amniocentesis was performed under ultrasonographic guidance at the discretion of the treating physician in a subset of patients presenting with PTL or PPROM for the determination of the microbiologic state of the amniotic cavity. Amniotic fluid was transported to the laboratory in a capped plastic sterile syringe and cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria as well as for genital mycoplasmas. White blood cell (WBC) count, glucose concentration and Gram-stain for microorganisms were performed in amniotic fluid shortly after collection.

Placental histopathological examinations

Chorioamniotic membranes containing maternal decidua were obtained from placentas delivered by spontaneous labor or Cesarean section at the Hutzel Women’s Hospital (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI). Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Five µm paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined using bright-field light microscopy. Histopathological examinations were performed by pathologists blinded to the clinical information based on the diagnostic criteria previously described[56]. Histological chorioamnionitis was diagnosed in the presence of acute inflammation in the fetal membranes, chorionic plate of the placenta or umbilical cord using previously described criteria[57,58].

Total RNA extraction

Fetal membranes were dissected from placentas, rinsed thoroughly with a sterile ice-cold phosphate buffered saline solution (Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO), cut into small pieces, placed in RNAlater solution (Ambion, Austin, TX), and stored at 4C° for no longer than two weeks. Total RNA was isolated with a modification of the standard guanidinium isothiocyanate-cesium chloride method[9,59]. Briefly, tissues were homogenized with a PRO200 rotor-stator homogenizer (Pro Scientific Inc, Monroe, CT) in the presence of 4 mol/L guanidinium isothiocyanate, 0.1 mol/L mercaptoethanol, 0.5% sarkosyl, and 5 mmol/L sodium citrate (pH 7). Solid CsCl was added to the samples in a final concentration of 0.25 g/mL, and then the samples were pelleted by ultracentrifugation according to the protocol. RNA pellets were resuspended and extracted with chloroform: isoamylalcohol, and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol and glycogen (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) as a carrier. Before the first use, the RNA was pelleted and resuspended in water that contained RNasin (Promega Corp, Madison, WI).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

2.5 µg total RNA from each sample and a positive control sample was reverse transcribed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase, random hexamer primers and oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). The standard curve was run with MnSOD mRNA and 18S ribosomal RNA to determine the quantity of cDNA needed for an approximate cycle threshold (Ct) of 25. Subsequently, cDNA derived from an equivalent of 75 ng RNA from each sample were run in triplicate on 96 well plates to obtain technical replicates for both the target and reference assays. A “calibrator” sample was run in triplicate in all plates to account for plate effects. In addition, a negative control containing no RNA and 12.5 ng of human genomic DNA were also tested in duplicates. Samples from the study groups were randomly allocated on the plates; the MnSOD and 18S rRNA assays were run with the same allocation on the parallel plates. The qPCR reactions were assembled based on the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix protocol (Applied Biosystems), using the 18S rRNA TaqMan gene expression assay (Hs99999901_s1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for the quantification of the housekeeping gene and self-designed primers and probe (forward primer: 5'-TTCTGGACAAACCTCAGCCC-3'; reverse primer: 5'-CGTTTGATGGCTTCCAGCA-3'; probe: 5'-CCCTTTGGGTTCTCCACCACCGTT-3') for MnSOD mRNA. Data was collected by the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups were compared using the Pearson’s chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test for proportions, and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR data were analyzed using the R statistical software[60].

Gene expression levels were profiled in multiple sample groups by qRT-PCR experiments, using between 12 and 29 samples per group. The RT reactions were run on 96 well plates. Samples from the study groups were randomly allocated on the plates, and the target gene and the 18S reference assay were run in parallel on each given plate. Each reaction was repeated either two or three times to obtain technical replicates for both the target assay and the reference assay. A “calibrator” patient sample was placed on all plates to account for eventual plate effects. Briefly, the delta-delta method[61,62] was used to generate an outcome variable, Y, which is a surrogate of the log2 concentration of the target gene in each patient sample, corrected already for potential plate effects.

A linear model was employed in which Y values were fitted using the Group variable and the gestational age as predictors without including the interaction term between these two variables. The coefficients of the two predictors in the linear model were estimated together with their significance p-values.

The outcome variable, Y, included also a positive constant to render the Y values positive so that large values correspond to high expression. A False Discovery Rate adjustment[63] of resulting p-values was performed to account for all parallel tests. For each pair-wise comparison, the Group effect was considered significant, if the adjusted p-values were < 0.05 and the magnitude of change was at least 2-fold (one Ct unit difference). For the gestational age effect, adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographic, clinical and histopathologic data

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups are displayed in Table I. The diagnosis of chorioamnionitis was stratified based on the presence of either maternal or fetal inflammatory response. Among patients with PPROM and histological chorioamnionitis, 7 had a marked maternal inflammatory response, two had fetal inflammatory response, and 12 had both. Among patients with PTL and chorioamnionitis, a maternal inflammatory response was diagnosed in one case, while 11 patients had both maternal and fetal inflammatory responses. Amniocentesis was performed in case of 14 patients with PPROM and 10 patients with PTL. Among these, positive amniotic fluid culture was detected in 64.2% (9/14) of patients with PPROM and in 40% (4/10) of patients with PTL. Microorganisms detected in amniotic fluid cultures are presented in Table II.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Term not in labor (n=29) |

Term in labor (n=29) |

p- value |

PPROM (n=17) |

PPROM with chorioamnionitis (n=21) |

p- value |

PTL (n=16) |

PTL with chorioamnionitis (n=12) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (yr)1 | 29 [22–33] | 22 [19–25] | 0.001 | 27 [22–31] | 27 [22–34] | NS | 24 [18–28] | 21 [18–30] | NS |

|

Gestational age at diagnosis (wk) 1 |

- | - | 31 [30–32.9] | 30 [25.6–31.4] | NS | 26 [23.1– 31.8] |

28.9 [25.5–32] | NS | |

|

Gestational age at delivery (wk) 1 |

39.1 [38.7– 39.4] |

40 [39.6–40.4] | <0.001 | 31.7 [30.1– 33.1] |

31 [29.1–32.3] | NS | 29.6 [24.2– 33.1] |

29.1 [25.6–32] | NS |

|

Diagnosis to delivery interval (d) 1 |

- | - | 1 [0–5] | 3 [1–10] | NS | 3 [0.3–5] | 1 [0–6.5] | NS | |

| Gravidity1 | 3 [2.5–4.5] | 2 [1–4] | NS | 3 [1.5–6] | 4 [2.5–5.5] | NS | 3 [1–4] | 3 [1.3–3] | NS |

| Parity1 | 2 [1–2] | 1 [0–2] | <0.05 | 2 [0–3.5] | 2 [1–4] | NS | 1 [1–2] | 0.5 [0–1] | NS |

| Birth-weight (g)1 | 3370 [3160–3765] |

3220 [3100–3580] |

NS | 1530 [1365–1850] |

1700 [995–1920] |

NS | 1040 [705–1870] |

1045 [670–1683] |

NS |

| Female fetus (%)2 | 41.4 (12/29) | 65.5 (19/29) | NS | 29.4 (5/17) | 33.3 (7/21) | NS | 25 (4/16) | 58.3 (7/12) | NS |

|

Positive amniotic fluid culture (%)2,4 |

- | - | 0 (0/8) | 46.2 (6/14) | 0.051 | 0 (0/11) | 30 (3/10) | NS | |

| Ethnic origin (%)3 | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| African-American | 65.5 (19/29) | 93.1 (27/29) | 82.4 (14/17) | 90.5 (19/21) | 87.5 (14/16) |

83.3 (10/12) | |||

| Caucasian | 13.8 (4/29) | 3.4 (1/29) | 17.6 (3/17) | 9.5 (2/21) | 12.5 (2/16) | 16.7 (2/12) | |||

| Other | 20.7 (6/29) | 3.4 (1/29) | 0 (0/17) | 0 (0/21) | 0 (0/16) | 0 (0/12) | |||

Values are presented as median [interquartile range] or percentage.

NS: Statistically not significant.

Comparisons between two groups were performed with the Mann–Whitney test,

Fisher’s exact test and

Pearson’s chi–square test.

PPROM (n=8); PPROM with chorioamnionitis (n=14); PTL (n=11); PTL with chorioamnionitis (n=10).

Table II.

Microorganisms detected in positive amniotic fluid cultures

| PPROM with chorioamnionitis (n=14) |

PTL with chorioamnionitis (n=10) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Ureoplasma ureolyticum |

3 | 1 |

| Mycoplasma hominis | 1 | 2 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 2 | - |

| Lactobacillus species | - | 1 |

|

Peptostreptococcus species |

1 | - |

| Prevotella species | 1 | - |

| Candida albicans | 1 | - |

MnSOD mRNA expression is increased in term and preterm labor

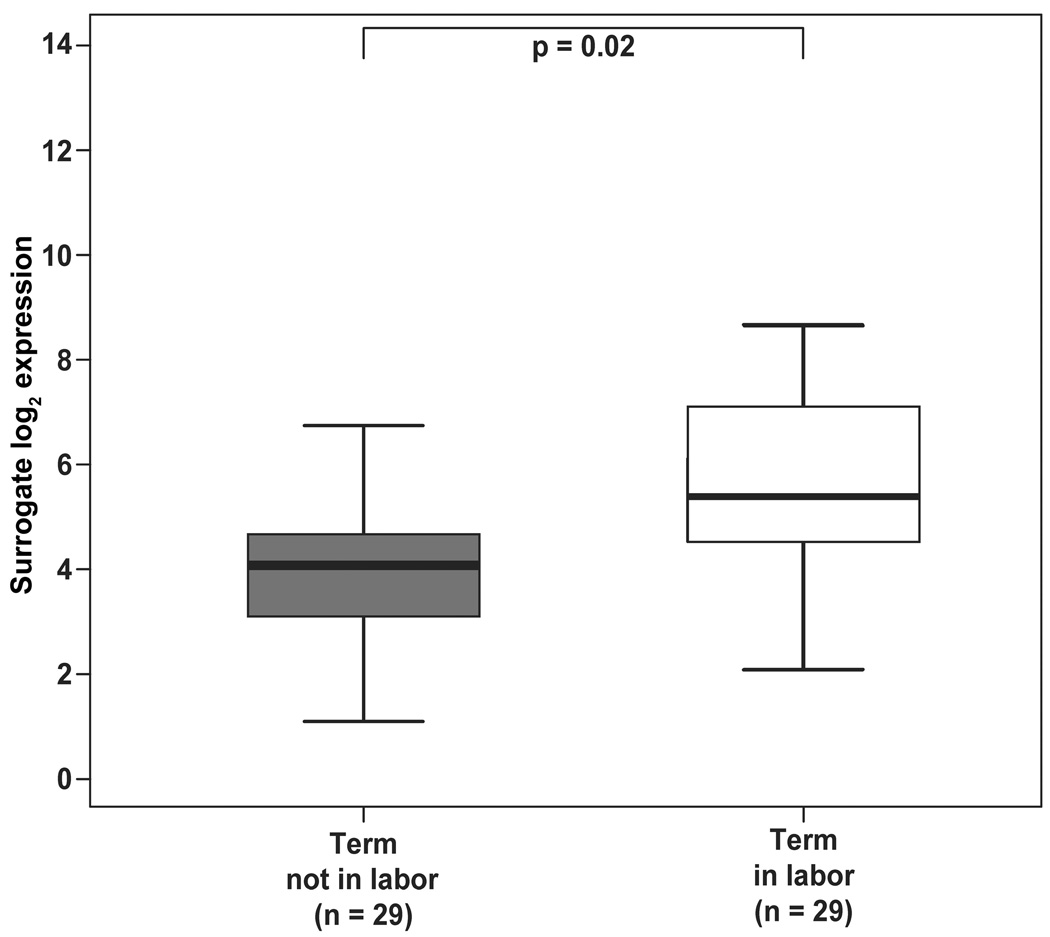

MnSOD mRNA expression did not change with gestational age in any of the groups. MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was 2.4-fold higher in women with spontaneous labor than in those who were not in labor at term (p=0.02; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MnSOD mRNA expression was 2.4-fold higher in the fetal membranes of women with spontaneous labor than in women who were not in labor at term (p=0.02). Groups are represented by different colors. Y-axis represents units of -delta Ct with an arbitrary zero point, so that each unit measures a 2-fold change.

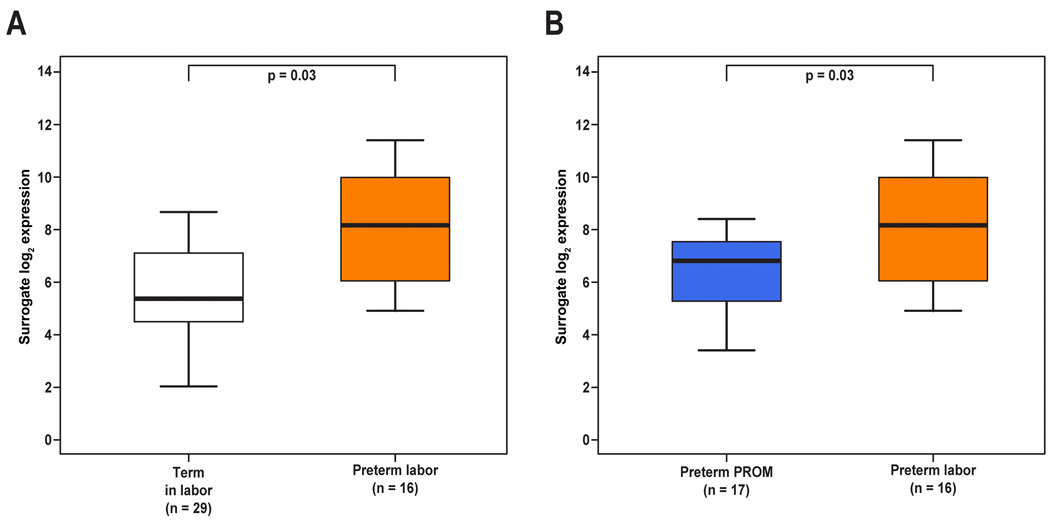

Patients with preterm labor without histological chorioamnionitis had a higher MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes than that of women in spontaneous labor at term (7.2-fold, p=0.03; Figure 2A) and those with PPROM without histological chorioamnionitis (3.2-fold, p=0.03; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The amount of MnSOD mRNA was higher in the fetal membranes of patients presenting with spontaneous preterm labor without histological chorioamnionitis than (A) in women with spontaneous labor at term (7.2-fold, p=0.03) or (B) in patients presenting with preterm PROM without histological chorioamnionitis (3.2-fold, p=0.03).

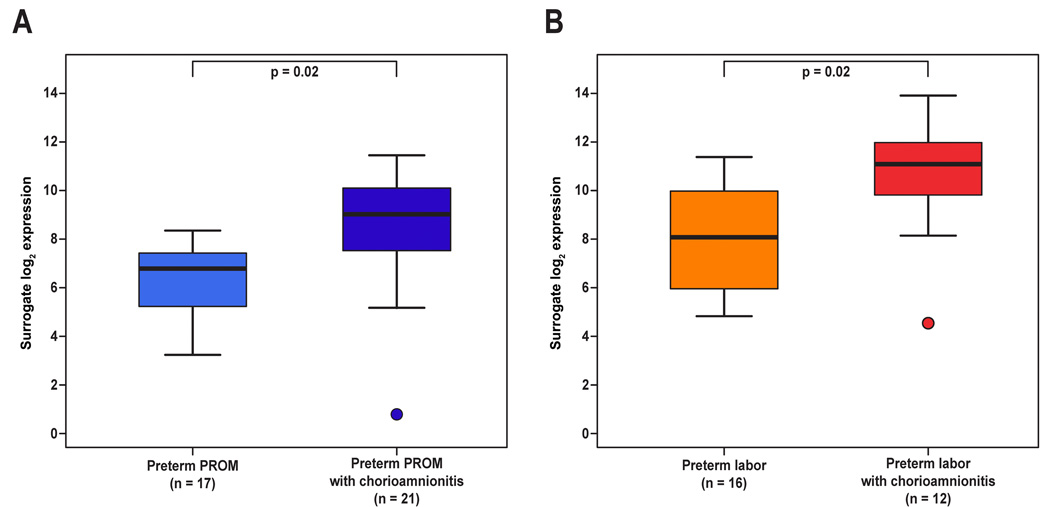

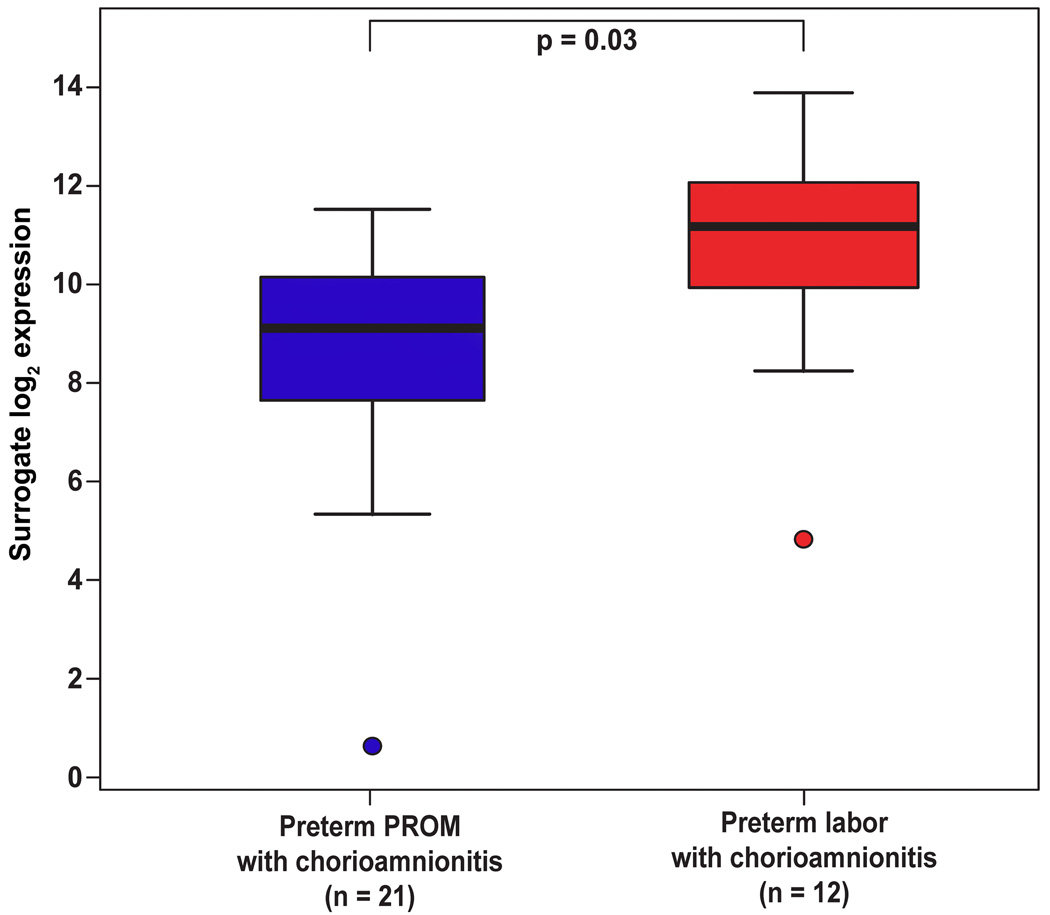

Increased MnSOD mRNA expression with the presence of histological chorioamnionitis and fetal female gender

Histological chorioamnionitis was associated with higher MnSOD mRNA expression among patients with PPROM (3.8-fold, p=0.02; Figure 3A) as well as those with PTL (5.4-fold, p=0.02; Figure 3B) when compared to those without histological chorioamnionitis. Among patients with histological chorioamnionitis, MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was higher in patients with PTL than in those with PPROM (4.3-fold, p=0.03; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was increased when histological chorioamnionitis was present both in patients with (A) preterm PROM (3.8-fold, p=0.02) or (B) spontaneous preterm labor (5.4-fold, p=0.02).

Figure 4.

MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was higher in patients with spontaneous preterm labor and chorioamnionitis than in those with preterm PROM and chorioamnionitis (4.3-fold, p=0.03).

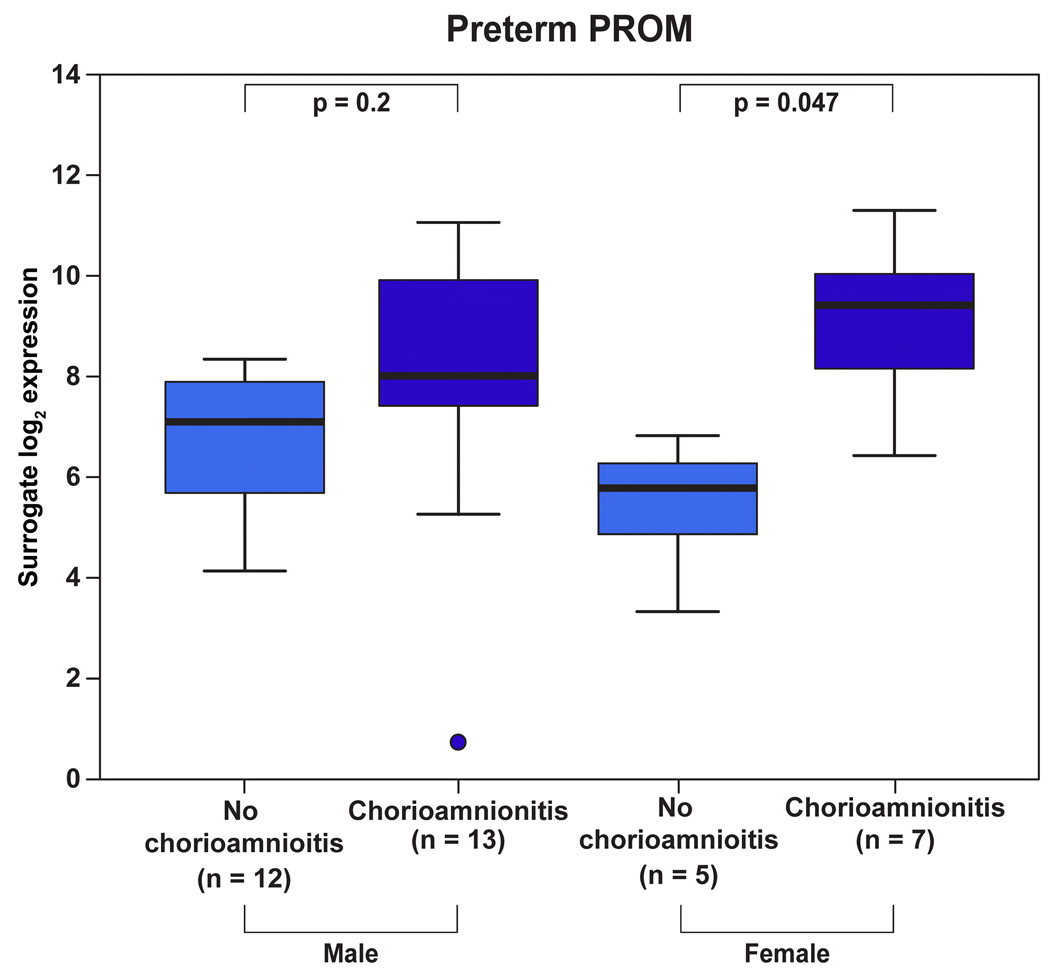

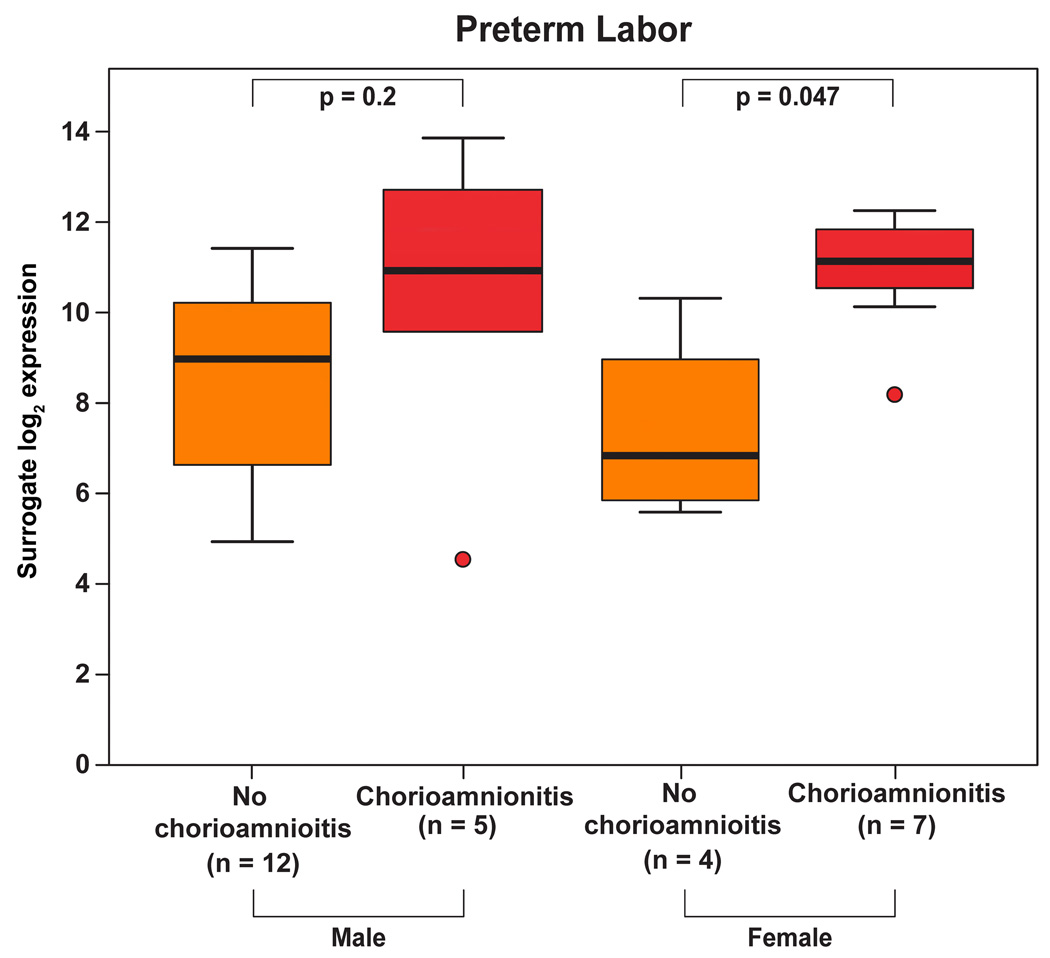

There was a significant interaction between fetal gender and the presence of histological chorioamnionitis in patients with PPROM and PTL overall (p=0.033). The presence of histological chorioamnionitis resulted in a 13.4-fold increase in MnSOD mRNA expression in patients with PPROM (p=0.047, Figure 5) and in a 12-fold increase in patients with PTL (p=0.047, Figure 6) who delivered a female neonate. A similar pattern in the changes of MnSOD mRNA levels was observed in patients with PTL and PPROM who delivered a male neonate; however, these differences were not significant (PPROM: 2.3-fold, p=0.2, Figure 5; PTL: 3.5-fold, p=0.2, Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Among patients with preterm PROM, those who delivered a female neonate had a higher increase (13.4-fold, p=0.047) in MnSOD mRNA expression upon chorioamnionitis than those who delivered a male neonate (2.3-fold, p=0.2).

Figure 6.

Among patients with spontaneous preterm labor, those who delivered a female neonate had a higher increase (12-fold, p=0.047) in MnSOD mRNA expression upon chorioamnionitis than those who delivered a male neonate (3.5-fold, p=0.2).

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of this study

1) MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was higher in women in labor than in those not in labor at term; 2) Patients with PTL had a higher MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes than women at term in labor or patients with PPROM; 3) Histological chorioamnionitis was associated with increased MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes among patients with PTL or PPROM; 4) Among patients with histological chorioamnionitis, MnSOD mRNA expression was higher in those with PTL than in those with PPROM; 5) Among patients with PPROM or PTL, female fetuses had a greater increase in MnSOD mRNA expression in the chorioamniotic membranes in chorioamnionitis than males.

Reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and mitochondrial MnSOD

Oxygen is consumed for the generation of ATP in the mitochondria of aerobic cells to produce water in a reaction catalyzed by cytochrome C oxidase[16,23,43]. However, the mitochondrial electron transport chain is also a major generator of ROS, as approximately 1–3% of the oxygen forms superoxide anion by both complexes I and III, which are mainly released into the mitochondrial matrix[16] and then are converted to hydrogen peroxide either spontaneously or by MnSOD[16,23,43]. Hydrogen peroxide is normally detoxified by glutathione peroxidase to form water, but its increased amounts are also converted to additional free oxygen radicals, such as hydroxyl radical (•OH)[16]. Besides in the mitochondria, ROS may also be generated by nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases, cyclooxygenases or in peroxisomes[16,32].

Reactive oxygen species are continuously produced and have beneficial effects in low concentrations, being secondary messengers in intracellular signaling pathways and having an important role in gene transcription, cell proliferation, metabolism, and apoptosis[14,16]. ROS also have a pivotal role in host defense against infectious agents, as being essential for phagocyte killing during the respiratory burst[15,16]. Moreover, ROS have been implicated in the regulation of a variety of physiological processes in human reproduction, such as follicular development, cyclic endometrial changes, fertilization, or embryo development[33].

In contrast, the overproduction of ROS has deleterious effects by causing oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA[28,43,64]. Consequently, oxidative stress plays a key role in cellular aging and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of a broad range of diseases, such as atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, cancer, diabetes[16–19,23,28,32,43,44]. Oxidative stress may also lead to an altered fate of trophoblastic cells, and is implicated in the pathophysiology of spontaneous abortions, embryopathies, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, and preterm labor[20–22,24–27,29–31,33–42,65–67]. An inverse relationship between mitochondrial ROS production and longevity was also observed in different species[68–72].

Superoxide dismutases are antioxidant enzymes that protect cells against the harmful effects of ROS and maintain physiological redox balance[10–13,16,73]. There are four known classes of SODs that differ by 1) their protein structure, 2) the redox-active metal ions (Cu/Zn, Fe, Mn or Ni) in their catalytic center and 3) their intra- or extracellular localization[11]. Mn and Fe SODs have a similar protein fold, whereas the Cu/Zn and Ni SODs are structurally distinct[11]. MnSOD was first discovered in E. coli, and later it was found to be highly conserved in all species from bacteria to humans[12,74]. In humans, MnSOD is encoded by SOD2 which is located on chromosome 6q25.3. The encoded polypeptide subunit is synthesized in the cytosol and imported into the mitochondrial matrix, where its N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence is cleaved[10]. In eukaryotes, MnSOD is a homotetramer with the Mn-binding sites at the interfaces[11,13].

MnSOD scavenges mitochondrial ROS and has a pivotal role in the first line of protection against oxidative stress in the mitochondria[10,12,13]. It is not surprising that increased MnSOD expression protects against pro-apoptotic stimuli and ischemic damage and results in an extended life-span in yeast, while the knockout of MnSOD results in severe mitochondrial disease, neonatal lethality in mice, and in a critically reduced life-span in yeast and Drosophila[16,44,70,72,75–80]. Deficient activity of MnSOD is associated with several human diseases, including cancers, aging, progeria, transplant rejection or asthma[78].

Increased MnSOD expression upon oxidative stress and inflammation

Recent data provided evidence that ROS physiologically regulate immune signaling pathways, and that increased oxidative stress results in the exaggerated activation of the redox-sensitive AP-1, NF-κB, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and MAPK signal transduction pathways, which subsequently leads to an enhanced generation of proinflammatory molecules, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-8, or COX-2, which then orchestrate inflammation[39,45,81–89]. Exaggerated inflammatory processes then, in turn, lead to the increased generation of ROS, oxidative stress and tissue injury[47,90].

Of importance, MnSOD expression is significantly up-regulated in sites of inflammation by both ROS and pro-inflammatory mediators[48,50,91–94]. ROS may stimulate MnSOD expression through TNF-α or toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 but NF-κB activation and N-acetylcysteine can reliably decrease this effect[87,93]; lipopolysaccharide (LPS) up-regulates MnSOD through CD14 and TLR-4[94]; and TNF-β, IL-1α, and IL-1β may also stimulate the overexpression of MnSOD mRNA[48]. In fact, the SOD2 promoter contains consensus binding sites for transcription factors such as AP-1, AP-2, NF-κB, SP-1, which can be responsible for its overexpression upon cellular redox changes and inflammation[95–97].

It has been suggested that increased ROS production triggers cellular antioxidant defence mechanisms, and up-regulation of MnSOD expression may be protective against cell injury caused by inflammation and oxidative stress[48,49]. Indeed, treatment with antioxidants can effectively block innate and adaptive immune responses through the following mechanisms: 1) inhibiting LPS-induced TLR-4 and NF-kB signaling and IL-8 transactivation[87]; 2) suppressing LPS-stimulated generation of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and ROS [98]; 3) reducing cytotoxic T-cell response and allograft rejection[99]; or 4) generating antigen-specific hyporesponsiveness of T-cells[89]. In fact, the overexpression of MnSOD suppresses TNF-induced apoptosis, LPS-induced activation of NF-κB pathway as well as TNF-mediated activation of AP-1, stress-activated c-Jun protein kinase, and MAPK kinase[51,52]. As immunoregulatory proteins such as galectin-1, indole 2,3-dioxygenase, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-β, contain redox-sensitive cysteine residues[86,100–104] and their activity is highly dependent on the redox status[12,86], MnSOD may also have important immunoregulatory effects through modification of the activity of these proteins.

Up-regulation of MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes upon term and preterm labor

Our study has shown that MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was 2.4-fold higher in women in labor than in those not in labor at term. This finding is in agreement with our previous microarray data[8], which showed the 2.6-fold up-regulation of SOD2 in the fetal membranes from women in labor compared to non-laboring women at term[8]. MnSOD protein was shown to be ubiquitously produced by the fetal membranes and the myometrium in another study[105], revealing an intense MnSOD immunostaining of the amnion and the decidua, a moderate immunostaining of extravillous trophoblasts and a faint immunostaining of the chorion, myocytes and myometrial endothelial cells[105]. However, the strength of the immunostaining and MnSOD enzyme activity did not differ between tissue samples collected before or after the onset of labor either in the fetal membranes or in the myometrium[105].

Of importance, MnSOD is also expressed by the syncytiotrophoblast and endothelial and stromal cells of the human villous placenta[105,106]. MnSOD protein synthesis was shown to be up-regulated in placentas delivered after a short labor (<5 hours) compared to non-laboring controls. In parallel, evidence for oxidative stress, activation of the p38 MAPK and NF-κB pathways, and an increase in COX-2 and proinflammatory cytokines in the same tissues was also presented[107]. Therefore, Cindrova-Davies et al. suggested that this up-regulation of MnSOD may be a transient compensatory mechanism for coping with the increased oxidative stress during term parturition[107]. Our findings support this concept and suggest that the acute inflammatory process in the fetal membranes during term parturition is associated with the up-regulation of MnSOD expression[8] to compensate for oxidative stress. However, functional experiments are needed to prove this hypothesis.

Our study has also revealed that MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes was 7.2-fold higher in spontaneous preterm labor than in spontaneous labor at term in cases without histological signs of chorioamnionitis. As MnSOD mRNA expression did not change with gestational age in any of the groups, this finding cannot simply be the consequence of the difference in the gestational ages in the two groups. Our findings also confirm the differences between physiological and pathological processes involved in term and preterm parturition[1] and also suggest that the extent of oxidative stress and inflammatory processes in preterm labor are greater than that of in term parturition. Evidence in support of this concept was reported by Keelan et al. who have shown a marked 4.5–6 and 2.8–5-fold increases in the concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) in the amnion and the choriodecidua in spontaneous preterm labor compared to spontaneous labor at term[108] and suggested it as evidence for the exaggerated inflammatory activation of the membranes in PTL[1,3,109]. This interpretation is consistent with our previous observations by measuring the concentration of a wide range of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in amniotic fluid[110–120]. As MnSOD mRNA expression was higher (3.2-fold) in PTL than in PPROM in our study, it may also imply significant differences in the redox status and the pathological process in the fetal membranes between these two syndromes[1,3,109,121–125].

Up-regulation of MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes upon chorioamnionitis

This study has shown that the amount of MnSOD mRNA was significantly higher in the fetal membranes of those patients with PTL or PPROM who had chorioamnionitis. This result is in good agreement with the above discussed phenomenon on the up-regulation of MnSOD mRNA expression in sites of inflammation[48,50,91–94]. Of importance, our finding that MnSOD mRNA expression was significantly higher in PTL than in PPROM either with (4.3-fold, p=0.03) or without (3.2-fold, p=0.03) inflammation in the fetal membranes suggests a deficient anti-oxidant production in PPROM compared to PTL, which may lead to a higher oxidative stress and may contribute to the different clinical presentation of these obstetrical syndromes. These observations are consistent with our previous reports that the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and chemokines such as IL-8 are greater in preterm labor with intact membranes with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation than in women with preterm PROM with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation[111,114,118,126,127].

Although intra-amniotic infection and inflammation are a major cause of spontaneous preterm birth, and cytokines, chemokines and innate immune molecules play a central role in the mechanisms of disease in cases of PPROM and PTL[1,3,5,9,108,109,121,124,125,128–134], recent studies have revealed that there are fundamental differences in the pathogenesis of these two syndromes[9,124,125,132]. As reviewed by Woods[135], ROS formation and / or anti-oxidant depletion during pregnancy may lead to extensive changes in collagen metabolism, consequent tissue damage, and premature rupture of the chorioamniotic membranes[135], and that the supplemental administration of antioxidant vitamins C and E may decrease PPROM[135,136]. Interestingly, women who subsequently presented with PPROM had higher first trimester amniotic fluid concentrations of isoprostanes, an oxidative stress biomarker, than those women who delivered at term, suggesting the association between an early oxidative stress and PPROM[137].

A synergistic effect of the presence of histological chorioamnionitis and fetal gender on MnSOD mRNA expression in the fetal membranes

Another important finding of this study is that among patients with PTL and PPROM, female fetuses had a greater increase in MnSOD mRNA expression in their chorioamniotic membranes in histological chorioamnionitis than male fetuses. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence in humans and rats that MnSOD expression is higher in females than in males[28,43]. This observation was attributed to the regulation of MnSOD expression by estrogens[28,43], which has a critical role in human reproduction. Indeed, MnSOD expression undergoes cyclic changes during the menstrual cycle in the human endometrium, where it has a pivotal role in protecting decidual stromal cells from ROS during decidualization and in the establishment of pregnancy[43,53,138,139].

SOD2 is one of the most important genes associated with longevity[12], and according to the free radical and mitochondrial theories of aging[17,18], MnSOD has been implicated in the relatively longer lifespan of females compared to males[28,43]. This may also have obstetrical implications since a higher incidence of preterm birth (PTB) and PPROM has been observed among women delivering male newborns compared with female newborns in different populations[140]. In a recent review, Di Renzo et al. reported that male gender is an independent risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome with a higher incidence of preterm birth and worse outcome in the perinatal period[141].

Moreover, Clifton et al. have previously shown that fetal gender has a fundamental influence on both endocrine and immune regulation during pregnancies complicated by asthma[142–145]. It is tempting to speculate that the gender difference in the regulation of MnSOD mRNA expression with inflammation in the fetal membranes may have an impact on pregnancy outcome through the regulation of redox status and inflammatory processes.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a potential compensatory anti-oxidant mechanism for MnSOD in the fetal membranes when exposed to oxidative stress and inflammation, and imply that gender differences may influence the redox balance and immunoregulation within the fetal membranes in chorioamnionitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported (in part) by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. The authors wish to acknowledge the Lark Technologies, Inc. (Houston, TX) for performing the qRT-PCR experiments. We appreciate the invaluable contributions of Sandy Field, Gerardo Rodriguez and the nursing staff of the Perinatology Research Branch and the Detroit Medical Center for this manuscript. We thank Sara Tipton for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic J, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazor M. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113 Suppl 3:17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero R, Mazor M. Infection and preterm labor. Clin.Obstet.Gynecol. 1988;31:553–584. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero R, Mazor M, Munoz H, Gomez R, Galasso M, Sherer DM. The preterm labor syndrome. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 1994;734:414–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaren J, Malak TM, Bell SC. Structural characteristics of term human fetal membranes prior to labour: identification of an area of altered morphology overlying the cervix. Hum.Reprod. 1999;14:237–241. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marvin KW, Keelan JA, Eykholt RL, Sato TA, Mitchell MD. Use of cDNA arrays to generate differential expression profiles for inflammatory genes in human gestational membranes delivered at term and preterm. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2002;8:399–408. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keelan JA, Blumenstein M, Helliwell RJ, Sato TA, Marvin KW, Mitchell MD. Cytokines, prostaglandins and parturition--a review. Placenta. 2003;24 Suppl A:S33–S46. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haddad R, Gould BR, Romero R, Tromp G, Farookhi R, Edwin SS, Kim MR, Zingg HH. Uterine transcriptomes of bacteria-induced and ovariectomy-induced preterm labor in mice are characterized by differential expression of arachidonate metabolism genes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddad R, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Mazor M, Romero R. Human spontaneous labor without histologic chorioamnionitis is characterized by an acute inflammation gene expression signature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:394–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Kim MR, Maymon E, Edwin S. Genome-wide expression profiling of fetal membranes reveals a deficient expression of proteinase inhibitor 3 in premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisiger RA, Fridovich I. Mitochondrial superoxide simutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J Biol.Chem. 1973;248:4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittaker JW. The irony of manganese superoxide dismutase. Biochem.Soc.Trans. 2003;31:1318–1321. doi: 10.1042/bst0311318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landis GN, Tower J. Superoxide dismutase evolution and life span regulation. Mech.Ageing Dev. 2005;126:365–379. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culotta VC, Yang M, O'Halloran TV. Activation of superoxide dismutases: putting the metal to the pedal. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2006;1763:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittal CK, Murad F. Activation of guanylate cyclase by superoxide dismutase and hydroxyl radical: a physiological regulator of guanosine 3',5'-monophosphate formation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1977;74:4360–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decoursey TE, Ligeti E. Regulation and termination of NADPH oxidase activity. Cell Mol.Life Sci. 2005;62:2173–2193. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int.J Biochem.Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HARMAN D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miquel J, Economos AC, Fleming J, Johnson JE., Jr Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp.Gerontol. 1980;15:575–591. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyall F, Gibson JL, Greer IA, Brockman DE, Eis AL, Myatt L. Increased nitrotyrosine in the diabetic placenta: evidence for oxidative stress. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1753–1758. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myatt L, Kossenjans W, Sahay R, Eis A, Brockman D. Oxidative stress causes vascular dysfunction in the placenta. J Matern.Fetal Med. 2000;9:79–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<79::AID-MFM16>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham CH, Postovit LM, Park H, Canning MT, Fitzpatrick TE. Adriana and Luisa Castellucci award lecture 1999: role of oxygen in the regulation of trophoblast gene expression and invasion. Placenta. 2000;21:443–450. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadenas E, Davies KJ. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:2111–2122. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton GJ, Caniggia I. Hypoxia: implications for implantation to delivery-a workshop report. Placenta. (Suppl A) 2001;22:S63–S65. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poston L, Chappell LC. Is oxidative stress involved in the aetiology of pre-eclampsia? Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2001;90:3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2001.tb01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myatt L. Role of placenta in preeclampsia. Endocrine. 2002;19:103–111. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:19:1:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vina J, Sastre J, Pallardo F, Borras C. Mitochondrial theory of aging: importance to explain why females live longer than males. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2003;5:549–556. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burton GJ, Hempstock J, Jauniaux E. Oxygen, early embryonic metabolism and free radical-mediated embryopathies. Reprod Biomed.Online. 2003;6:84–96. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)62060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E. Placental oxidative stress: from miscarriage to preeclampsia. J.Soc.Gynecol.Investig. 2004;11:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myatt L, Cui X. Oxidative stress in the placenta. Histochem.Cell Biol. 2004;122:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol.Endocrinol. 2005;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderlelie J, Venardos K, Clifton VL, Gude NM, Clarke FM, Perkins AV. Increased biological oxidation and reduced anti-oxidant enzyme activity in pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta. 2005;26:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webster RP, Brockman D, Myatt L. Nitration of p38 MAPK in the placenta: association of nitration with reduced catalytic activity of p38 MAPK in pre-eclampsia. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2006;12:677–685. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webster RP, Macha S, Brockman D, Myatt L. Peroxynitrite treatment in vitro disables catalytic activity of recombinant p38 MAPK. Proteomics. 2006;6:4838–4844. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Jauniaux E. Working with oxygen and oxidative stress in vitro. Methods Mol.Med. 2006;122:413–425. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jauniaux E, Poston L, Burton GJ. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: Involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Hum.Reprod.Update. 2006;12:747–755. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugino N, Takiguchi S, Umekawa T, Heazell A, Caniggia I. Oxidative stress and pregnancy outcome: a workshop report. Placenta. 2007;28 Suppl A:S48–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ornoy A. Embryonic oxidative stress as a mechanism of teratogenesis with special emphasis on diabetic embryopathy. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta S, Agarwal A, Banerjee J, Alvarez JG. The role of oxidative stress in spontaneous abortion and recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:335–347. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000261644.89300.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webster RP, Roberts VH, Myatt L. Protein nitration in placenta - functional significance. Placenta. 2008;29:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vina J, Sastre J, Pallardo FV, Gambini J, Borras C. Modulation of longevity-associated genes by estrogens or phytoestrogens. Biol.Chem. 2008;389:273–277. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shadel GS. Expression and maintenance of mitochondrial DNA: new insights into human disease pathology. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1445–1456. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugino N, Karube-Harada A, Taketani T, Sakata A, Nakamura Y. Withdrawal of ovarian steroids stimulates prostaglandin F2alpha production through nuclear factor-kappaB activation via oxygen radicals in human endometrial stromal cells: potential relevance to menstruation. J Reprod Dev. 2004;50:215–225. doi: 10.1262/jrd.50.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belt AR, Baldassare JJ, Molnar M, Romero R, Hertelendy F. The nuclear transcription factor NF-kappaB mediates interleukin-1beta-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human myometrial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks T, Moldow CF, Craddock PR, Bowers TK, Jacob HS. Endothelial damage provoked by toxic oxygen radicals released from complement-triggered granulocytes. Prog.Clin.Biol.Res. 1978;21:719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong GH, Goeddel DV. Induction of manganous superoxide dismutase by tumor necrosis factor: possible protective mechanism. Science. 1988;242:941–944. doi: 10.1126/science.3263703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada T, Matsuzaki N, Sawai K, Nobunaga T, Shimoya K, Suzuki K, Taniguchi N, Saji F, Murata Y. Chorioamnionitis reduces placental endocrine functions: the role of bacterial lipopolysaccharide and superoxide anion. J Endocrinol. 1997;155:401–410. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1550401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugino N, Telleria CM, Gibori G. Differential regulation of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and manganese superoxide dismutase in the rat corpus luteum: induction of manganese superoxide dismutase messenger ribonucleic acid by inflammatory cytokines. Biol.Reprod. 1998;59:208–215. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manna SK, Zhang HJ, Yan T, Oberley LW, Aggarwal BB. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB and activated protein-1. J Biol.Chem. 1998;273:13245–13254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oberley LW. Mechanism of the tumor suppressive effect of MnSOD overexpression. Biomed.Pharmacother. 2005;59:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strehlow K, Rotter S, Wassmann S, Adam O, Grohe C, Laufs K, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Modulation of antioxidant enzyme expression and function by estrogen. Circ.Res. 2003;93:170–177. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000082334.17947.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet.Gynecol. 1996;87:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J, Yoshimatsu J, Kim YM, Bujold E, Edwin S, Yoon BH, Romero R. Activation of coagulation system in preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of membranes. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:368–373. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.6.368.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Redline RW, Heller D, Keating S, Kingdom J. Placental diagnostic criteria and clinical correlation--a workshop report. Placenta. 2005;26 Suppl A:S114–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pacora P, Chaiworapongsa T, Maymon E, Kim YM, Gomez R, Yoon BH, Ghezzi F, Berry SM, Qureshi F, Jacques SM, et al. Funisitis and chorionic vasculitis: the histological counterpart of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:18–25. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.1.18.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Redline RW. Inflammatory responses in the placenta and umbilical cord. Semin.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 60.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winer J, Jung CK, Shackel I, Williams PM. Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal.Biochem. 1999;270:41–49. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(− Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav.Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gerschman R, Gilbert DL, Nye SW, Dwyer P, Fenn WO. Oxygen poisoning and x-irradiation: a mechanism in common. Science. 1954;119:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.119.3097.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moll SJ, Jones CJ, Crocker IP, Baker PN, Heazell AE. Epidermal growth factor rescues trophoblast apoptosis induced by reactive oxygen species. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1611–1622. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heazell AE, Moll SJ, Jones CJ, Baker PN, Crocker IP. Formation of syncytial knots is increased by hyperoxia, hypoxia and reactive oxygen species. Placenta. 2007;28 Suppl A:S33–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heazell AE, Taylor NN, Greenwood SL, Baker PN, Crocker IP. Does altered oxygenation or reactive oxygen species alter cell turnover of BeWo choriocarcinoma cells? Reprod Biomed.Online. 2009;18:111–119. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sohal RS, Svensson I, Brunk UT. Hydrogen peroxide production by liver mitochondria in different species. Mech.Ageing Dev. 1990;53:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90039-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ku HH, Brunk UT, Sohal RS. Relationship between mitochondrial superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production and longevity of mammalian species. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 1993;15:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90165-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Longo VD, Gralla EB, Valentine JS. Superoxide dismutase activity is essential for stationary phase survival in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mitochondrial production of toxic oxygen species in vivo. J Biol.Chem. 1996;271:12275–12280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barja G, Herrero A. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is inversely related to maximum life span in the heart and brain of mammals. FASEB J. 2000;14:312–318. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fabrizio P, Liou LL, Moy VN, Diaspro A, Valentine JS, Gralla EB, Longo VD. SOD2 functions downstream of Sch9 to extend longevity in yeast. Genetics. 2003;163:35–46. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J Biol.Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keele BB, Jr, McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase from escherichia coli B. A new manganese-containing enzyme. J Biol.Chem. 1970;245:6176–6181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat.Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lebovitz RM, Zhang H, Vogel H, Cartwright J, Jr, Dionne L, Lu N, Huang S, Matzuk MM. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, Tuinstra R, Cottrell B, Jun AS, Zastawny TH, Dizdaroglu M, Goodman SI, Huang TT, et al. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1999;96:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macmillan-Crow LA, Cruthirds DL. Invited review: manganese superoxide dismutase in disease. Free Radic.Res. 2001;34:325–336. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kirby K, Hu J, Hilliker AJ, Phillips JP. RNA interference-mediated silencing of Sod2 in Drosophila leads to early adult-onset mortality and elevated endogenous oxidative stress. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2002;99:16162–16167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252342899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Duttaroy A, Paul A, Kundu M, Belton A. A Sod2 null mutation confers severely reduced adult life span in Drosophila. Genetics. 2003;165:2295–2299. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sen CK, Packer L. Antioxidant and redox regulation of gene transcription. FASEB J. 1996;10:709–720. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muller JM, Rupec RA, Baeuerle PA. Study of gene regulation by NF-kappa B and AP-1 in response to reactive oxygen intermediates. Methods. 1997;11:301–312. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suzuki YJ, Forman HJ, Sevanian A. Oxidants as stimulators of signal transduction. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 1997;22:269–285. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dong W, Simeonova PP, Gallucci R, Matheson J, Fannin R, Montuschi P, Flood L, Luster MI. Cytokine expression in hepatocytes: role of oxidant stress. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:629–638. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fan J, Marshall JC, Jimenez M, Shek PN, Zagorski J, Rotstein OD. Hemorrhagic shock primes for increased expression of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant in the lung: role in pulmonary inflammation following lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1998;161:440–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sen CK. Redox signaling and the emerging therapeutic potential of thiol antioxidants. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1998;55:1747–1758. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ryan KA, Smith MF, Jr, Sanders MK, Ernst PB. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species differentially regulate Toll-like receptor 4-mediated activation of NF-kappa B and interleukin-8 expression. Infect.Immun. 2004;72:2123–2130. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2123-2130.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matsuzawa A, Saegusa K, Noguchi T, Sadamitsu C, Nishitoh H, Nagai S, Koyasu S, Matsumoto K, Takeda K, Ichijo H. ROS-dependent activation of the TRAF6-ASK1-p38 pathway is selectively required for TLR4-mediated innate immunity. Nat.Immunol. 2005;6:587–592. doi: 10.1038/ni1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tse HM, Milton MJ, Schreiner S, Profozich JL, Trucco M, Piganelli JD. Disruption of innate-mediated proinflammatory cytokine and reactive oxygen species third signal leads to antigen-specific hyporesponsiveness. J Immunol. 2007;178:908–917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taylor DE, Ghio AJ, Piantadosi CA. Reactive oxygen species produced by liver mitochondria of rats in sepsis. Arch Biochem.Biophys. 1995;316:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ho YS, Dey MS, Crapo JD. Antioxidant enzyme expression in rat lungs during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L810–L818. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sugino N, Nakata M, Kashida S, Karube A, Takiguchi S, Kato H. Decreased superoxide dismutase expression and increased concentrations of lipid peroxide and prostaglandin F(2alpha) in the decidua of failed pregnancy. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2000;6:642–647. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.7.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rogers RJ, Monnier JM, Nick HS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha selectively induces MnSOD expression via mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling, whereas interleukin-1beta utilizes an alternative pathway. J Biol.Chem. 2001;276:20419–20427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsan MF, Clark RN, Goyert SM, White JE. Induction of TNF-alpha and MnSOD by endotoxin: role of membrane CD14 and Toll-like receptor-4. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1422–C1430. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.St Clair DK, Porntadavity S, Xu Y, Kiningham K. Transcription regulation of human manganese superoxide dismutase gene. Methods Enzymol. 2002;349:306–312. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)49345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robinson CJ, Johnson DD, Chang EY, Armstrong DM, Wang W. Evaluation of placenta growth factor and soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor levels in mild and severe preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2006;195:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mattson MP, Meffert MK. Roles for NF-kappaB in nerve cell survival, plasticity, and disease. Cell Death.Differ. 2006;13:852–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tse HM, Milton MJ, Piganelli JD. Mechanistic analysis of the immunomodulatory effects of a catalytic antioxidant on antigen-presenting cells: implication for their use in targeting oxidation-reduction reactions in innate immunity. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2004;36:233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tocco G, Illigens BM, Malfroy B, Benichou G. Prolongation of alloskin graft survival by catalytic scavengers of reactive oxygen species. Cell Immunol. 2006;241:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hirabayashi J, Kasai K. Effect of amino acid substitution by sited-directed mutagenesis on the carbohydrate recognition and stability of human 14-kDa beta-galactoside-binding lectin. J Biol.Chem. 1991;266:23648–23653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol.Endocrinol. 1996;10:1077–1083. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang JG, Matthews JM, Ward LD, Simpson RJ. Disruption of the disulfide bonds of recombinant murine interleukin-6 induces formation of a partially unfolded state. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2380–2389. doi: 10.1021/bi962164r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Poljak A, Grant R, Austin CJ, Jamie JF, Willows RD, Takikawa O, Littlejohn TK, Truscott RJ, Walker MJ, Sachdev P, et al. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase activity by H2O2. Arch Biochem.Biophys. 2006;450:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Than NG, Romero R, Erez O, Weckle A, Tarca AL, Hotra J, Abbas A, Han YM, Kim SS, Kusanovic JP, et al. Emergence of hormonal and redox regulation of galectin-1 in placental mammals: implication in maternal-fetal immune tolerance. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008;105:15819–15824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807606105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Telfer JF, Thomson AJ, Cameron IT, Greer IA, Norman JE. Expression of superoxide dismutase and xanthine oxidase in myometrium, fetal membranes and placenta during normal human pregnancy and parturition. Hum.Reprod. 1997;12:2306–2312. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.10.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Myatt L, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Kossenjans W, Greer IA, Lyall F. Differential localization of superoxide dismutase isoforms in placental villous tissue of normotensive, pre-eclamptic, and intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. J Histochem.Cytochem. 1997;45:1433–1438. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cindrova-Davies T, Yung HW, Johns J, Spasic-Boskovic O, Korolchuk S, Jauniaux E, Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS. Oxidative stress, gene expression, and protein changes induced in the human placenta during labor. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1168–1179. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Keelan JA, Marvin KW, Sato TA, Coleman M, McCowan LM, Mitchell MD. Cytokine abundance in placental tissues: evidence of inflammatory activation in gestational membranes with term and preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1530–1536. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel LA, Nien JK. Inflammation in preterm and term labour and delivery. Semin.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Romero R, Brody DT, Oyarzun E, Mazor M, Wu YK, Hobbins JC, Durum SK. Infection and labor. III. Interleukin-1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1989;160:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Romero R, Manogue KR, Mitchell MD, Wu YK, Oyarzun E, Hobbins JC, Cerami A. Infection and labor. IV. Cachectin-tumor necrosis factor in the amniotic fluid of women with intraamniotic infection and preterm labor. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1989;161:336–341. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Romero R, Avila C, Santhanam U, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin 6 in preterm labor. Association with infection. J.Clin.Invest. 1990;85:1392–1400. doi: 10.1172/JCI114583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Romero R, Mazor M, Sepulveda W, Avila C, Copeland D, Williams J. Tumor necrosis factor in preterm and term labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1576–1587. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91636-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Romero R, Mazor M, Brandt F, Sepulveda W, Avila C, Cotton DB, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta in preterm and term human parturition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1992;27:117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1992.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Romero R, Yoon BH, Kenney JS, Gomez R, Allison AC, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6 determinations are of diagnostic and prognostic value in preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1993;30:167–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1993.tb00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maymon E, Ghezzi F, Edwin SS, Mazor M, Yoon BH, Gomez R, Romero R. The tumor necrosis factor alpha and its soluble receptor profile in term and preterm parturition 158. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1999;181:1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Athayde N, Romero R, Maymon E, Gomez R, Pacora P, Araneda H, Yoon BH. A role for the novel cytokine RANTES in pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:989–994. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Esplin MS, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Edwin S, Gomez R, Mazor M, Adashi EY. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 is increased in the amniotic fluid of women who deliver preterm in the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:365–373. doi: 10.1080/14767050500141329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Athayde N, Romero R, Maymon E, Gomez R, Pacora P, Yoon BH, Edwin SS. Interleukin 16 in pregnancy, parturition, rupture of fetal membranes, and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hamill N, Romero R, Gotsch F, Pedro KJ, Edwin S, Erez O, Than NG, Mittal P, Espinoza J, Friel LA, et al. Exodus-1 (CCL20): evidence for the participation of this chemokine in spontaneous labor at term, preterm labor, and intrauterine infection. J Perinat.Med. 2008;36:217–227. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Romero R, Mazor M, Wu YK, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, Mitchell MD, Hobbins JC. Infection in the pathogenesis of preterm labor. Semin.Perinatol. 1988;12:262–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bryant-Greenwood GD, Millar LK. Human fetal membranes: their preterm premature rupture. Biol.Reprod. 2000;63:1575–1579. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1575b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mercer BM. Preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Obstet.Gynecol. 2003;101:178–193. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Srinivas SK, Macones GA. Preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes: current concepts. Minerva Ginecol. 2005;57:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Santolaya-Forgas J, Romero R, Espinoza J, Erez O, Friel LA, Kusanovic JP, Bahado-Singh R, Nien JK. Prelabor rupture of the membranes. In: Reece EA, Hobbins JC, editors. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus and Mother. 3rd ed. Blackwell Publishing; 2007. pp. 1130–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Romero R, Gomez R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Edwin SS, Berry SM. A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1998;179:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Espinoza J, Kim YM, Edwin S, Bujold E, Gomez R, Kuivaniemi H. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with preterm parturition and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. J Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:405–416. doi: 10.1080/14767050500361703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Romero R, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, Avila C, Mazor M, Callahan R, Sabo V, Athanassiadis AP, Hobbins JC. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intraamniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1989;161:817–824. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Romero R, Ceska M, Avila C, Mazor M, Behnke E, Lindley I. Neutrophil attractant/activating peptide-1/interleukin-8 in term and preterm parturition. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1991;165:813–820. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90422-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Parry S, Strauss JF., III Premature rupture of the fetal membranes. N.Engl.J Med. 1998;338:663–670. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tashima LS, Millar LK, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Genes upregulated in human fetal membranes by infection or labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:441–449. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fortunato SJ, Menon R. Distinct molecular events suggest different pathways for preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1399–1405. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kim YM, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim GJ, Kim MR, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Espinoza J, Bujold E, Abrahams VM, et al. Toll-like receptor-2 and -4 in the chorioamniotic membranes in spontaneous labor at term and in preterm parturition that are associated with chorioamnionitis. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2004;191:1346–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Pineles BL, Gotsch F, Mittal P, Than NG, Espinoza J, Hassan SS. Recurrent preterm birth. Semin.Perinatol. 2007;31:142–158. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Woods JR., Jr Reactive oxygen species and preterm premature rupture of membranes-a review. Placenta. 2001;22 Suppl A:S38–S44. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J. Micronutrients and intrauterine infection, preterm birth and the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. J Nutr. 2003;133:1668S–1673S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1668S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Longini M, Perrone S, Vezzosi P, Marzocchi B, Kenanidis A, Centini G, Rosignoli L, Buonocore G. Association between oxidative stress in pregnancy and preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clin.Biochem. 2007;40:793–797. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sugino N, Kashida S, Takiguchi S, Nakamura Y, Kato H. Induction of superoxide dismutase by decidualization in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2000;6:178–184. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sugino N. The role of oxygen radical-mediated signaling pathways in endometrial function. Placenta. 2007;28 Suppl A:S133–S136. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.McGregor JA, Leff M, Orleans M, Baron A. Fetal gender differences in preterm birth: findings in a North American cohort. Am J Perinatol. 1992;9:43–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Di Renzo GC, Rosati A, Sarti RD, Cruciani L, Cutuli AM. Does fetal sex affect pregnancy outcome? Gend.Med. 2007;4:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Clifton VL, Murphy VE. Maternal asthma as a model for examining fetal sex-specific effects on maternal physiology and placental mechanisms that regulate human fetal growth. Placenta. 2004;25 Suppl A:S45–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Clifton VL. Sexually dimorphic effects of maternal asthma during pregnancy on placental glucocorticoid metabolism and fetal growth. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Clifton VL, Vanderlelie J, Perkins AV. Increased anti-oxidant enzyme activity and biological oxidation in placentae of pregnancies complicated by maternal asthma. Placenta. 2005;26:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Murphy VE, Gibson P, Talbot PI, Clifton VL. Severe asthma exacerbations during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1046–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185281.21716.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]