Abstract

Background and purpose:

We have previously shown that lipid mediators, produced by phospholipase D and C, are generated in OX1 orexin receptor signalling with high potency, and presumably mediate some of the physiological responses to orexin. In this study, we investigated whether the ubiquitous phospholipase A2 (PLA2) signalling system is also involved in orexin receptor signalling.

Experimental approach:

Recombinant Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells, expressing human OX1 receptors, were used as a model system. Arachidonic acid (AA) release was measured from 3H-AA-labelled cells. Ca2+ signalling was assessed using single-cell imaging.

Key results:

Orexins strongly stimulated [3H]-AA release (maximally 4.4-fold). Orexin-A was somewhat more potent than orexin-B (pEC50= 8.90 and 8.38 respectively). The concentration–response curves appeared biphasic. The release was fully inhibited by the potent cPLA2 and iPLA2 inhibitor, methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate, whereas the iPLA2 inhibitors, R- and S-bromoenol lactone, caused only a partial inhibition. The response was also fully dependent on Ca2+ influx, and the inhibitor studies suggested involvement of the receptor-operated influx pathway. The receptor-operated pathway, on the other hand, was partially dependent on PLA2 activity. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase, but not protein kinase C, were involved in the PLA2 activation at low orexin concentrations.

Conclusions and implications:

Activation of OX1 orexin receptors induced a strong, high-potency AA release, possibly via multiple PLA2 species, and this response may be important for the receptor-operated Ca2+ influx. The response coincided with other high-potency lipid messenger responses, and may interact with these signals.

Keywords: orexin, hypocretin, OX1 receptor, phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid, PLA2, iPLA2, cPLA2, Ca2+ influx

Introduction

The orexin receptors, OX1 and OX2 (nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2008), constitute a family of G-protein-coupled receptors with a wide spectrum of engaged intracellular signalling pathways (see Kukkonen and Åkerman, 2005). These receptors, or specifically OX1 receptors, which have been a target for most investigations, have been shown to connect to multiple Ca2+ signalling mechanisms in all the native and recombinant cell types where this has been investigated (see Kukkonen and Åkerman, 2005). Based on detailed analyses, orexin receptors, at low orexin concentrations, have been suggested to activate primarily a receptor-operated Ca2+ influx pathway (Lund et al., 2000; Kukkonen and Åkerman, 2001), and at higher concentrations, orexins also activate a phospholipase C (PLC)-dependent Ca2+ release and a secondary (store-operated) Ca2+ influx (Kukkonen and Åkerman, 2001; Johansson et al., 2007). Transient receptor potential (TRP) family non-selective cation channels have in some cases been suggested to mediate the primary influx (Larsson et al., 2005; Näsman et al., 2006), but these channels may even in these cases be responsible for only a part of the response. In the native cells, the identity of the channels involved is not known, nor are the mechanisms utilized for channel activation in orexin receptor signalling. Ca2+ influx seems to be important for orexin receptor signalling at different levels. The receptor-operated influx couples orexin receptors to several signal pathways, including the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), adenylyl cyclase and part of the PLC response (Ammoun et al., 2006a; Johansson et al., 2007). The store-operated pathway amplifies the PLC response and may sometimes substitute for the receptor-operated pathway (Ammoun et al., 2006a; Johansson et al., 2007).

Furthermore, a more recently discovered signalling system significantly targeted by orexin receptors involves lipid messengers. We have previously shown that orexin receptor activation regulates both PLC and phospholipase D (PLD) species (Lund et al., 2000; Holmqvist et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2008), which generate at least the messengers phosphatidic acid (PA), diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), and subsequently most likely other derivatives of these as well. Lipid messengers represent likely candidates to regulate many types of Ca2+ channels (reviewed in Delmas et al., 2005; Montell, 2005), and are thus also candidates for the orexin receptor-operated Ca2+ channel activation, albeit they might also affect other orexin receptor responses, such as cell plasticity and death.

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes cleave the sn2-linked acyl chain of glycerophospholipids, although several PLA2 species are not strictly specific for the sn2 linkage (reviewed inSix and Dennis, 2000; Leslie, 2004). PLA2 enzymes (more than 20 are known) are commonly divided into three or four major types of secreted PLA2s (sPLA2; GI-III, -V, -IX–XIV PLA2 families), cytosolic PLA2s (cPLA2; GIV PLA2 family), Ca2+-independent PLA2s (iPLA2; GVI PLA2 family) and lipoprotein-associated PLA2 (Lp-PLA2; also known as platelet-activating factor acetyl hydrolase and GVIIA PLA2), of which cPLA2 and iPLA2 have been suggested to be receptor-regulated (seeAkiba and Sato, 2004; Leslie, 2004; Balsinde and Balboa, 2005; Ghosh et al., 2006; Schaloske and Dennis, 2006; Zalewski et al., 2006). cPLA2, but not iPLA2, enzymes are brought to their lipid substrates by Ca2+ elevation, which interacts with the C2-domain of cPLA2. Some members of the intracellular cPLA2 and iPLA2 have been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation, for instance by protein kinase C (PKC), Ca2+-calmodulin kinase II and mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) pathways (see Six and Dennis, 2000; Akiba and Sato, 2004; Leslie, 2004; Balsinde and Balboa, 2005; Ghosh et al., 2006). Arachidonic acid (AA) is classically thought to be a major product of PLA2 activity, although very few PLA2 isoforms show high specificity for AA. AA is, most importantly, a precursor for prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis, but it also acts directly as an intracellular, autocrine or paracrine messenger. One of the elusive AA targets is the AA-activated ARC channel (see Shuttleworth et al., 2004). ARC channels have been reported in a number of cell types using Ca2+ measurements or electrophysiology, and a significant amount of data have accumulated on their regulation, yet their molecular identity remains unclear. In addition, AA may modulate the activity of several other types of ion channels, such as TRP channels, Na+ channels, Cl– channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (see Delmas et al., 2005; Meves, 2008).

In this study, we set out to investigate the involvement of PLA2 in OX1 receptor signalling. We found a robust release of AA upon orexin receptor activation, with a pharmacology that indicates that PLA2 enzymes are indeed involved. The results also suggest involvement of PLA2 activity in orexin receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx.

Methods

Test systems used

Chinese hamster ovary cells, expressing human OX1 receptors (CHO-hOX1), have been described previously (Lund et al., 2000). CHO cells were propagated in Ham's F-12 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 100 U·mL–1 penicillin G (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), 80 U·mL–1 streptomycin (Sigma), 400 mg·mL–1 geneticin (G418; Gibco) and 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (Gibco) at 37°C in 5% CO2 in an air-ventilated humidified incubator on plastic culture dishes (56 cm2 bottom area; Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany). Wild-type (wt) CHO cells (not expressing OX1 receptors) were propagated under same conditions except that geneticin was omitted. For the 3H-AA release experiments, the cells were cultivated on Primaria 24-well plates (1.77 cm2 well bottom area; BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium), and for Ca2+ imaging, on uncoated circular glass coverslips (diameter 25 mm; Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany).

Transfection

Cells were transfected to introduce pcDNA3-InsP3-5-phosphatase-I (type I inositol-1,4,5-P3 5-phosphatase; here referred as IP3-5P1) (De Smedt et al., 1997); pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA; 10% of the total DNA) was used as a marker for transfected cells (both for IP3-5P1- and mock-transfected cells). Briefly, CHO-OX1-cells were grown to 40–50% confluence, washed with PBS and transfected in OPTI-MEM (Gibco) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Ammoun et al., 2006a; Johansson et al., 2007). After 5 h, this medium was replaced with fresh Ham's F-12 medium with the standard supplements (see above), and the cells were studied 48 h after the initiation of the transfection.The total amount of DNA was kept constant in all transfections using empty plasmids.

AA and oleic acid release

The experiments were performed essentially as described by Mounier et al. (2004). Cells were plated on 24-well plates (2 × 104 cells per well), and left to grow for 24 h. Then, 0.1 µCi [3H]-AA (or [3H]-oleic acid) was added to each well, and the cells were cultured for another 20 h. The incubation medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with the Na+-based medium (NaBM; composition in mM: NaCl, 137; KCl, 5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 1.2; KH2PO4, 0.44; NaHCO3, 4.2; glucose, 10; and HEPES, 20 adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH) supplemented with 2.4 mg·mL–1 bovine serum albumin (BSA), and finally left in NaBM without BSA at 37°C. The cells were then immediately stimulated with orexins, thapsigargin, ionomycin or 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) for 7 min, after which 200 µL of the total volume of 250 µL in each well was transferred to an Eppendorf tube on ice. These samples were centrifuged for 1.5 min at 4°C, and 100 µL of the medium was transferred to a scintillation tube. The cells on the 24-well plates were dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH, and transferred to separate scintillation vials. Scintillation cocktail (HiSafe 3, Wallac-PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland) was added, and the radioactivity was measured in a Wallac 1414 liquid scintillation counter.

In some cases, orexin stimulation was preceded by some inhibitor preincubation. In such cases, the inhibitor used was added to the cells after one wash with NaBM and the cells preincubated for 30 min in the absence of BSA. Then, the cells were washed once more with NaBM + BSA, changed to fresh NaBM without BSA still containing the inhibitor and immediately stimulated with orexin-A for 7 min. Controls (vehicle only) were treated in the same manner. This procedure was designed to remove the radioactivity leaking out of the cells during the preincubation period. For other inhibitors {TEA-BM [70 mM of the NaCl in NaBM replaced with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA)], KBM [all the Na+ salts replaced with corresponding K+ salts], SKF-96365 [1-(β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]-4-methoxyphenethyl)-1H-imidazole HCl]} not requiring such long preincubation periods, the inhibitors were added in NaBM without BSA after the two washes with NaBM + BSA, and the cells stimulated directly in this medium after a 5 min preincubation. Controls (vehicle only) were treated in the same manner.

Ca2+ measurements

Cellular Ca2+ measurements were performed as microfluorometric Ca2+ imaging of individual CHO cells attached on glass coverslips as described previously (Ammoun et al., 2006a). Briefly, the cells were loaded with 4 mM fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester for 20 min at 37°C in NaBM + 0.5 mM probenecid, rinsed once and used immediately. TILLvisION version 4.01 imaging system (TILL Photonics GmbH, Gräfelding, Germany) on Nikon TE200 fluorescence microscope (×20/0.5 air objective) was used for measurements. The cells were excited with 340 and 380 nm light from a xenon lamp through a monochromator, and the emitted light was collected through a 400 nm dichroic mirror and a 470 nm barrier filter with a high-resolution (1280 × 1024) cooled CCD camera. One 340 and one 380 reading were obtained each second, and the ratio was calculated after background subtraction.

The concentration of free Ca2+ ions in nominally Ca2+-free NaBM (no added CaCl2) was measured in FlexStation (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Ten nM CalciumGreen 5N free acid was included in this medium, and the Ca2+ concentration was calculated from the fluorescence utilizing the maximum and minimum defined by saturating Ca2+ concentration (1 mM) and 0 Ca2+ (10 mM EGTA), respectively.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

All the data are presented as mean ± SE; n refers to the number of batches of cells. Each experiment was performed at least three times. The AA release experiments were performed with six parallel data points, and in imaging regularly about 30 or more data points (cells per coverslip) were obtained in parallel. Student's two-tailed t-test with Bonferroni correction was used in all pairwise comparisons except for the data in Figure 4A and B, where, because of the non-parametric nature of cell counting, the χ2-test was used.

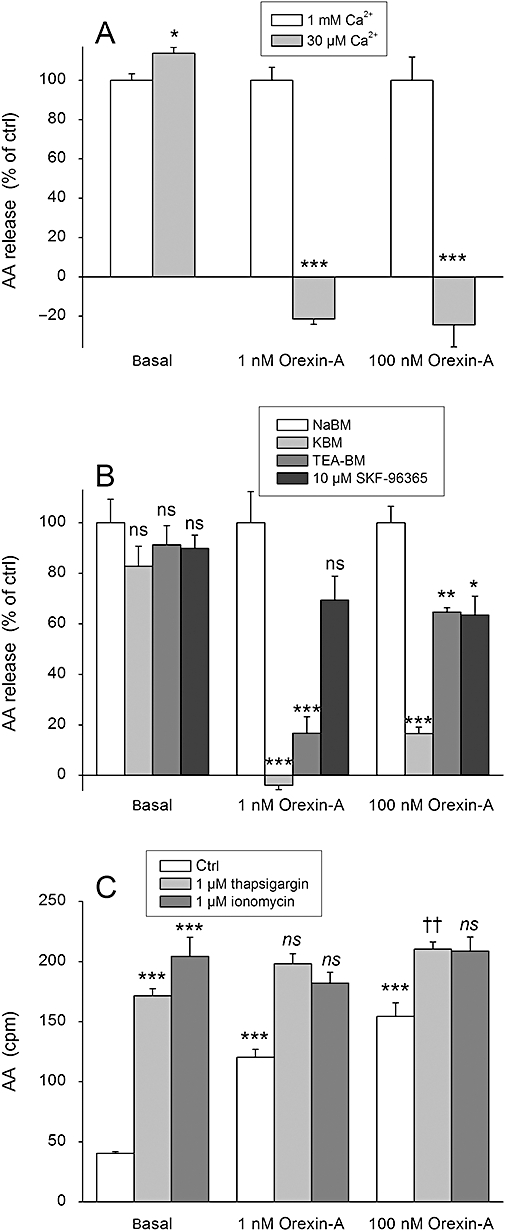

Figure 4.

The effect of Ca2+ on AA release in CHO-hOX1 cells. (A) The cells were stimulated with orexin-A in the normal extracellular concentration of Ca2+ (1 mM) or in the reduced concentration (30 µM) in NaBM. Data are normalized as explained in Data analysis and Figure 3. (B) The cells were, before stimulation with orexin-A, exposed to the treatments that reduce the driving force for Ca2+ entry (KBM) or inhibit particular Ca2+ channel types [TEA-BM (70 mM TEA), SKF-96395 (10 µM) ]. The cells were preincubated for 5 min in the presence of the specific medium/inhibitor before stimulation with orexin-A in the same medium. Data are normalized as explained in Data analysis and Figure 3. (C) The cells were stimulated with orexin-A in the absence (ctrl) or presence of the Ca2+-elevating compounds thapsigargin or ionomycin in NaBM. The first comparison (***) is to the basal (i.e. Do thapsigargin, ionomycin and orexin-A stimulate AA release over the basal?) and the second comparison (†† and ns) to thapsigargin or ionomycin (i.e. Does orexin-A stimulate AA release over thapsigargin or ionomycin?); ns (not significant), P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. ††P < 0.01.

Microsoft Excel was used for the non-linear curve fitting used for the determination of the EC50 values; fits obtained with different models were compared using the F-test individually for each batch of cells (Figure 2). The effect of inhibitors on the orexin-stimulated AA release was calculated from the cpm values using a formula that compensates for the possible effect of the inhibitors also on the basal release: release [in % of the ctrl (non-inhibited)]= (orexininhibitor– basalinhibitor)/(orexinctrl– basalctrl) × 100% (Figures 3–5). In this manner, the non-treated controls (basal, 1 nM orexin-A, 100 nM orexin-A) are set to 100%, and the full inhibition to 0%.

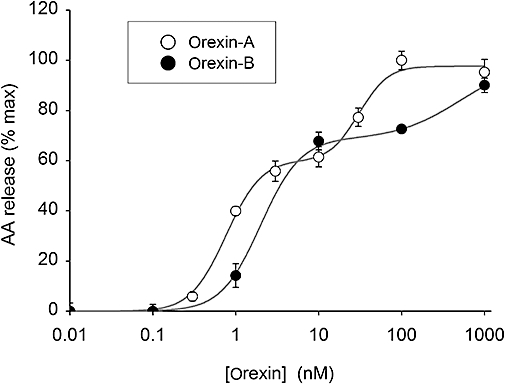

Figure 2.

Concentration–response relationships for orexin-A and orexin-B for AA release in CHO-hOX1 cells in NaBM. A two-site fit was significantly better (P < 0.001) than a one-site fit for both orexin-A and orexin-B.

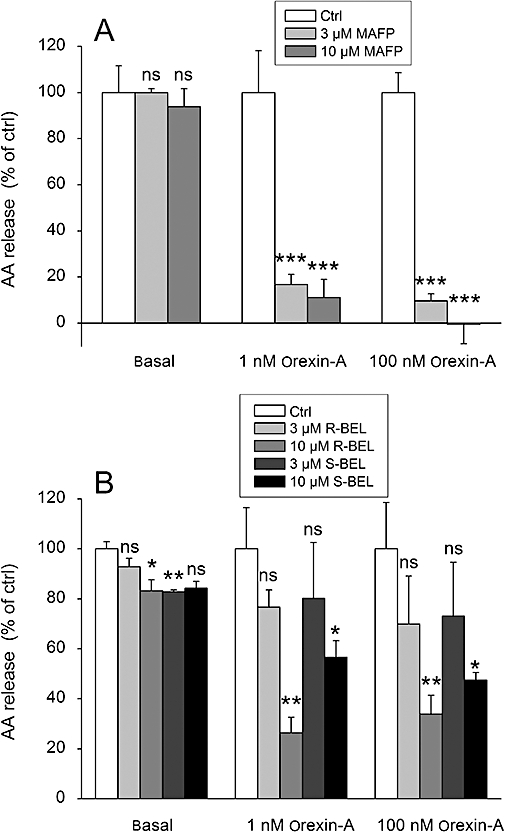

Figure 3.

The effect of the PLA2 inhibitors MAFP (A) and R- and S-BEL (B) on the orexin-A-stimulated AA release in CHO-hOX1 cells. The cells were preincubated for 30 min with the inhibitor, changed to fresh NaBM containing the inhibitor and immediately stimulated with orexin-A. The responses are normalized so that each control response (basal, 1 nM orexin-A, 100 nM orexin-A) amounts to 100% (see Data analysis); ns (not significant), P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

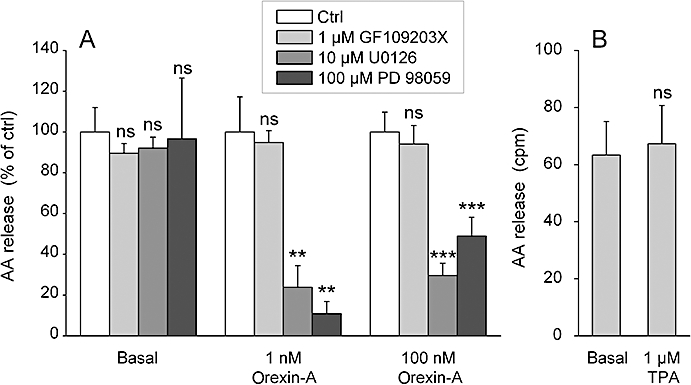

Figure 5.

The effect of PKC and ERK activation on AA release in CHO-hOX1 cells. (A) Cells were preincubated for 30 min with the MEK inhibitors U0126 and 98059 as indicated, changed to fresh NaBM containing the inhibitor and immediately stimulated with orexin-A. Data are normalized as explained in Data analysis and Figure 3. (B) Cells were stimulated with 1 mM TPA for 7 min in NaBM. ns (not significant), P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Materials

Human orexin-A and -B were from NeoMPS (Strasbourg, France), while the methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP), (R)-bromoenol lactone (R-BEL) and (S)-bromoenol lactone (S-BEL) were from Cayman Europe (Tallinn, Estonia). Ionomycin, SB-334867 (1-[2-methylbenzoxazol-6-yl]-3-[1,5]naphthyridin-4-yl-urea HCl), thapsigargin and U0126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[o-aminophenylmercapto]butadiene) were from Tocris Cookson Ltd. (Avonmouth, UK). GF109203X (= bisindolylmaleimide I = Gö6850 = 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide), PD 98059 (2-[2-amino-3-methoxyphenyl]-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one) and SKF-96365 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA); fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester and CalciumGreen 5N free acid were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA); and AA, EGTA, probenecid, TEA and TPA were from Sigma. [3H]-AA ([5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H]-AA) and [3H]-oleic acid ([9,10-3H]-oleic acid) were from New England Nuclear Corp. GesmbH (Wien, Austria).

Results

Orexin receptor stimulation strongly stimulates 3H-AA release

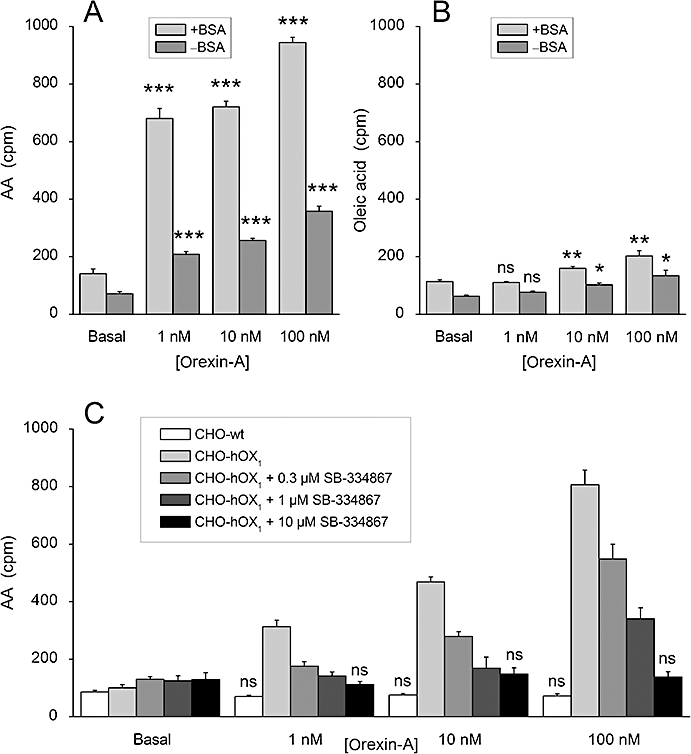

In order to measure PLA2 activity, we loaded CHO cells with 3H-AA and measured the released 3H-radioactivity. In the classical methodology, the released 3H-AA is sequestered by adding BSA to the medium (see Mounier et al., 2004). However, as the usual BSA contains fatty acids, and even the commercial ‘fatty acid-free’ BSA is seldom devoid of fatty acids (our unpublished observations), the addition of BSA may induce cell responses by itself. We thus first evaluated the necessity of including BSA in the assay. As seen in Figure 1A and B, both the basal and the orexin-A-stimulated releases were higher in the presence of BSA. As a very robust release was seen with orexin-A even in the absence of BSA, we decided to perform the rest of the experiments without BSA. Independent of the presence of the BSA, a much weaker orexin-stimulated release of radioactivity was observed from 3H-oleic acid-loaded cells than from 3H-AA-loaded cells (Figure 1A and B), indicating that this orexin receptor-stimulated enzyme activity prefers AA over oleic acid (for instance, cPLA2α[GIVA] or iPLA2ζ[GVIE] (Jenkins et al., 2004; Schaloske and Dennis, 2006).

Figure 1.

Orexin-A-stimulated 3H-AA (A, C) and 3H-oleic acid (B) release. (A and B) OX1 receptor-expressing CHO cells (CHO-hOX1) were used. The release was assessed in NaBM in the presence of 2.4 mg/mL BSA (+BSA) or in the absence of BSA (−BSA). (C) Both wild-type CHO cells (CHO-wt) and CHO-hOX1 cells were used, both in the absence of BSA. CHO-hOX1 cells were preincubated for 30 min with SB-334867, changed to fresh NaBM containing the SB-334867 and immediately stimulated with orexin-A. ns (not significant), P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; comparisons in all subfigures are to the corresponding basal in C, significances are only calculated for wild-type CHO cells and CHO-hOX1 with 10 µM SB-334867.

The basal level of release of 3H-AA was 0.44 ± 0.04% of the total incorporated radioactivity, and orexin-A stimulated the release by 4.4 ± 0.5-fold (n= 21, P < 0.001). The response was concentration-dependently inhibited by the OX1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867 (Smart et al., 2001) with full inhibition at 10 µM; also, no response was seen in CHO cells not expressing OX1 receptors (Figure 1C). This confirms that the response was specific for the OX1 receptor. While the maximum response to orexin-B was equal to the response to orexin-A [101 ± 3% of the response to orexin-A; n= 3, P > 0.05 (ns)], orexin-A was more potent than orexin-B (apparent pEC50= 8.9 ± 0.1 and 8.4 ± 0.1, respectively; n= 3, P < 0.05). We also observed clearly biphasic agonist concentration–response curves in each individual batch of cells (Figure 2). Altogether, 3H-AA release occurred much in the same concentration range as the high-potency DAG production by PLD and the high-potency PLC (Johansson et al., 2008).

Different PLA2 species are involved in the AA release

Traditionally, PLA2, and in particular cPLA2α, has been thought to be the key enzyme in AA release (Leslie, 2004). However, because orexin receptors also activate PLD and PLC, di- and monoacylglycerol lipases might also be involved. We found, here, that MAFP, a potent iPLA2 and cPLA2 inhibitor, fully inhibited the AA release at the concentrations of 3 and 10 µM (Figure 3A). In contrast, the selective iPLA2 inhibitors R- and S-BEL were significantly less active, and could only inhibit a specific component of the response even at an apparently saturating concentration (Figure 3B). Ten µM was considered to be a saturating concentration, as 25 µM did not produce any stronger inhibition, and as 25 µM of each BEL enantiomer produced a strong decrease in the basal AA release, we decided to use 10 µM. These data together thus indicate that both iPLA2 and cPLA2 are involved in the response. We could not observe any significant difference in the inhibitory potency of either BEL enantiomer (Figure 3B), which could be used as an indication of involvement of either iPLA2β (GVIA-1 or -2) or iPLA2γ (GVIB) (see Discussion and Conclusions). In contrast to MAFP, the effect of R- and S-BEL varied between different batches of cells (see, for instance, the size of the error bars for 3 µM R- and S-BEL in Figure 3B), indicating that the expression of the BEL-inhibited component may thus vary. In conclusion, several PLA2 species seem to be involved in the orexin-induced AA release, which could offer one explanation to the apparent biphasic concentration–response curves.

Ca2+ dependence of the AA release

The influx of Ca2+ is the most characteristic consequence of orexin receptor activation (Lund et al., 2000; Kukkonen and Åkerman, 2005), and it may mediate/amplify orexin receptor-mediated signals at different levels (Ammoun et al., 2006a; Johansson et al., 2007). In addition, cPLA2, based on the inhibitor activity of MAFP, may be the most likely candidate to mediate a part of the AA release response. We thus evaluated the role of Ca2+ influx in this response. Reduction of extracellular Ca2+ to 30 µM, from the normal 1 mM, abolished the AA release (Figure 4A). Ca2+ influx can be greatly decreased by depolarizing the cells with high-K+ medium (reduction of the driving force for Ca2+ entry; Larsson et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2007). Upon exposure of the cells to such medium (KBM), AA release was eliminated at 1 nM orexin-A and markedly inhibited at 100 nM orexin-A (Figure 4B). TEA has been suggested to strongly, although not fully, inhibit the receptor, but not the store-operated Ca2+ influx (Larsson et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2007). In our experiments, TEA (TEA-BM; 70 mM TEA), strongly inhibited AA release at 1 nM orexin-A, but less at 100 nM orexin-A (Figure 4B). In contrast, the store-operated Ca2+ influx blocker SKF-96365 (10 µM) (Johansson et al., 2007) only weakly inhibited AA release both at 1 and 100 nM orexin-A (Figure 4B).

Based on these results, intracellular Ca2+ elevation, more specifically Ca2+ influx, would be a strong candidate to mediate orexin receptor-induced AA release. We therefore exposed the cells to the Ca2+-elevating agents thapsigargin and ionomycin. Thapsigargin, by inhibiting the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), causes a modest Ca2+ release and a sustained Ca2+ influx via the store-operated Ca2+ channels (Ammoun et al., 2006a). The Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin, at high concentration, makes all the cellular membranes Ca2+ permeable, thus elevating the Ca2+ concentration in all cellular compartments to the level of the extracellular medium. Thus, thapsigargin may induce a more modest and localized Ca2+ elevation than ionomycin. Both thapsigargin and ionomycin (both at 1 µM) strongly activated AA release in CHO cells (Figure 4C). Orexin-A only very weakly stimulated Ca2+ release in the presence of thapsigargin, but not ionomycin.

ERK pathway, but not PKC, is involved in AA release

Phosphorylation has been identified as one major mechanism for cPLA2 and iPLA2 activation, and PKC and ERK have often been implicated in this process. Here, we have used an inhibitor of both conventional and novel PKC, GF109203X (1 µM) (see e.g. Holmqvist et al., 2005; Ammoun et al., 2006a), and found it did not inhibit the orexin receptor-induced AA release (Figure 5A). TPA (1 µM), an activator of these same PKC subfamilies, did not stimulate AA release (Figure 5B). It can thus be concluded that members of the conventional or novel subfamilies of PKC are unlikely to be involved in the orexin-induced AA release. In contrast, the MEK1/2 (MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2) inhibitors U0126 (10 µM) and PD98059 (100 µM) strongly inhibited AA release (Figure 5A), suggesting that the ERK pathway is partly involved in this response. The inhibition was clearly stronger at 1 nM orexin-A than at 100 nM.

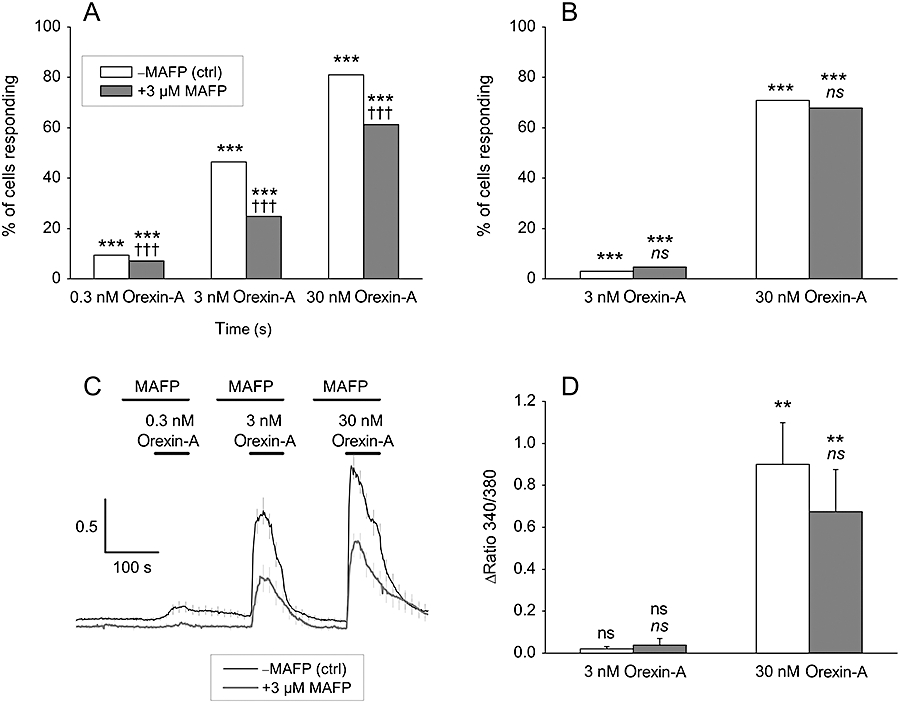

Modulation of Ca2+ signalling by AA

Ca2+ influx and release are central orexin receptor responses, and we thus wanted to investigate the putative interaction between AA and Ca2+ responses. To optimally target different components of the Ca2+ signal (see Ekholm et al., 2007), orexin-A concentrations of 0.3, 3 and 30 nM were used. The receptor-operated Ca2+ influx can be specifically investigated when the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent Ca2+ release is inhibited by over-expression of the IP3-hydrolyzing enzyme IP3-5-phosphatase type 1 (IP3-5P1) (Ekholm et al., 2007). Under these conditions, MAFP (3 µM) significantly reduced the number of cells responding with Ca2+ elevation (Figure 6A), and this effect was also clearly seen in the marked reduction of the average cell response (Figure 6C). Pure Ca2+ release-dependent Ca2+ responses can be investigated in isolation when Ca2+ is excluded from the bathing medium (no influx possible). Under these conditions, MAFP did not affect the cell responses, that is, the number of cells responding (Figure 6B) or the response magnitude (Figure 6D). These data thus strongly suggest that AA or its metabolites contribute to the orexin receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx, but not Ca2+ release.

Figure 6.

The effect of AA release inhibition on orexin-induced receptor-operated Ca2+ influx (A, C) and Ca2+ release (B, D) in CHO-hOX1 cells in NaBM. (A, C) Cells are over-expressing IP3-5P1, which precludes Ca2+ release. In (A) data from counting of responsive and non-responsive cells (n= 458–496 cells/treatment) and in (C) a representative experiment (n= 29–31 cells/trace). Some error bars (C) are omitted for purpose of clarity. (B, D) Cells were stimulated in nominally Ca2+-free conditions (no CaCl2 added to the NaBM), which gives an extracellular [Ca2+]≈ 2.5–3.3 µM as measured using CalciumGreen 5N, which is low enough concentration to abolish the Ca2+ influx. In (B) data from counting of responsive and non-responsive cells (n= 551–577 cells/treatment) and in (D) the average Ca2+ responses from these cells. The first comparisons (*/**/***) in (A, B and D) are to the basal (i.e. Does orexin cause a Ca2+ response?) and the second comparison (††† and ns) to the corresponding orexin response (i.e. Does MAFP inhibit the response to orexin-A?); ns (not significant), P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, †††P < 0.001.

Discussion and conclusions

We have shown here that activation of OX1 orexin receptors results in a marked release of AA, and the inhibitor profile suggests that PLA2 enzymes are responsible for this response. The orexin concentration–response curves and the inhibitor data suggest that more than one pathway regulates AA release. AA release observed links strongly to the Ca2+ signalling of the orexin receptors, much in the line of evidence from other responses such as ERK, adenylyl cyclase and PLC (Ammoun et al., 2006b; Johansson et al., 2007). On the other hand, AA released (or its metabolites) apparently itself modulates the Ca2+ influx.

Generally, AA is thought to be released from glycerophospholipids by PLA2 enzymes. That PLA2 would be responsible for the AA release upon orexin receptor activation is supported by the inhibitor experiments. MAFP, an inhibitor of both cPLA2 and iPLA2, efficiently inhibited AA release. The iPLA2-selective inhibitors R- and S-BEL induced only partial inhibition of the response. This suggests that both cPLA2 and iPLA2 may contribute to the AA release. R- and S-BEL show concentration-dependent selectivity for iPLA2γ and -β, respectively (Jenkins et al., 2002). We could not observe any significant selectivity, which may indicate that both γ- and β-isoforms are involved. However, it should be noted that the potencies or activities of the BEL enantiomers for other iPLA2β splice variants or other iPLA2 isoforms are not known. BEL enantiomers may not only show different affinities for different iPLA2 isoforms, but they may also display partial inhibition (Jenkins et al., 2002), which can complicate the analysis in a native cell putatively expressing several iPLA2 isoforms, like the cells in the current study. Finally, it should be noted that no PLA2 inhibitor shows absolute selectivity for PLA2 only, but may inhibit other lipid-metabolizing enzymes as well (see Akiba and Sato, 2004; Burke and Dennis, 2009). Therefore, although it seems rather likely that PLA2 species are primarily responsible for the AA release in response to orexin receptor stimulation, further studies are needed to exclude other possible enzymes. Under any circumstance, the biphasic orexin concentration–response curves, and the incomplete inhibition of the orexin response by the inhibitors of iPLA2 (BEL) and ERK suggest that several enzyme species are involved in the AA release response.

Ca2+ influx seems to hold an essential role in the AA release: when either the extracellular Ca2+ concentration or the driving force for Ca2+ entry was reduced, AA release was abolished. We utilized the previously devised approach to target the Ca2+ influx pathways (receptor- and store-operated influx) by the inhibitors TEA and SKF-96365, respectively (Johansson et al., 2007). These results suggest that the receptor-operated pathway is most important at 1 nM orexin-A and less than at 100 nM, while the store-operated pathway plays an altogether less significant part. This is remarkably similar to the regulation of PLC (Lund et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2007) A key question, though, is whether Ca2+ influx mediates the AA release response or if it rather plays a more permissive role in orexin receptor signalling, as has been suggested for the ERK, adenylyl cyclase and PLC responses (Ammoun et al., 2006b; Johansson et al., 2007). There is, however, one important difference between the AA release observed in the current study and the activation of ERK, adenylyl cyclase and PLC: while the latter are only weakly stimulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevation alone, that is, by thapsigargin or ionomycin (Ammoun et al., 2006b; Johansson et al., 2007), AA release was strongly stimulated by these Ca2+-elevating compounds. This supports the possibility that orexin receptor-induced Ca2+ influx could also directly activate AA release via cPLA2. This, however, would be contradictory to the BEL data, which suggest involvement of iPLA2 in this response as well, because Ca2+ may rather regulate iPLA2 in a negative manner (Jenkins et al., 2001; reviewed in Akiba and Sato, 2004). It would, though, be possible that Ca2+ influx activates iPLA2 indirectly. With the help of pharmacological inhibitors and activators, we could show that ERK, but not PKC, is likely to be involved in AA release. ERK is very strongly activated by OX1 receptors in CHO cells possibly with both cytosolic and nuclear targeting (Milasta et al., 2005; Ammoun et al., 2006a), and thus with different molecular targets (Shenoy and Lefkowitz, 2005). The ERK pathway constitutes one possible candidate target for Ca2+ influx-stimulated AA release. As pointed out earlier, ERK is only modestly activated by Ca2+ influx alone, as compared to the strong response triggered by orexin receptor activation (Ammoun et al., 2006a). However, this finding does not exclude the possibility of ERK being involved in AA release, and the levels of active ERK required for this may be much lower than the maximal. In summary, we conclude that the target(s) of Ca2+ influx and its modus operandi in AA release remain unresolved to date, and further experiments are thus needed.

What then could be the role of AA release in orexin receptor signalling? In this study, we observed a very marked inhibition of the receptor-operated Ca2+ influx when AA release was blocked by MAFP. This effect was clearly stronger than the inhibition obtained previously with the specific dominant-negative TRPC channels in CHO cells (Larsson et al., 2005). As exogenous AA did not appear to cause a Ca2+ influx response (our unpublished experiments) and there is, to our knowledge, no previous report of AA-induced Ca2+ influx in CHO cells, it may be that AA (or a metabolite of it) is a supporting factor in orexin receptor signalling to the receptor-operated Ca2+ influx. Interestingly, as Ca2+ influx, on the other hand, seems to be a key requirement for AA release, Ca2+ influx and AA release could constitute a positive feedback loop. However, although the release of AA was the parameter measured in this study, it is possible that another product of the phospholipase reaction, such as another fatty acid or a lysophospholipid, is more relevant for orexin receptor signalling to receptor-operated Ca2+ channels.

The concentration–response curves for orexin-A and -B showed untypical and unexpected features. First, the shape was significantly biphasic. In a recombinant cell system, as we have used here, it seems likely that the high and low potency components are generated by different signal cascades. Our previous studies suggest that orexin receptor responses in CHO cells may be put in a potency order of PLD > high potency PLC ≈ Ca2+ influx > low potency PLC > Gs (Lund et al., 2000; Holmqvist et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2007). Thus, the ability to activate different signal cascades at different agonist concentrations seems characteristic for orexin receptors. The reason for this is unknown, but processes such as affinity differences of activated receptors for particular G-proteins and preferential localization in signal complexes may be involved. We hope to resolve the factors governing AA release and also other determinants of the wide concentration–response range of orexin receptors in our future studies.

Another feature attracting attention was the weak preference for orexin-A over orexin-B, that is, twofold, that we have found in the present experiments, compared to the 10- to 100-fold preference expected (see Sakurai et al., 1998; Holmqvist et al., 2002; Ammoun et al., 2003). As recently shown, rank order of agonist efficacies may not be fixed for different responses due to ligand-selective receptor conformations (Kenakin, 1995; 2003; Kukkonen et al., 2001; Kukkonen, 2004). In the present context, orexin-A and -B potencies have mainly been determined with respect to Ca2+ elevation and PLC activation in recombinant cells. Nevertheless, orexin-A and orexin-B have been used in native tissues to determine the involvement of OX1 or OX2 receptors, a practice we have tried to discourage (Kukkonen et al., 2002). The results of the present study would strongly support caution in using orexin-A and -B for such ‘diagnostic’ purposes. Our data may also lead to re-evaluation of the physiological role of orexin-B. The OX1 receptor has been proposed to mediate signals only from orexin-A under physiological conditions, but the current results suggest that − at least selected − signals from orexin-B are also transduced. This calls for investigations of orexin-B with respect to many other OX1 receptor responses and of the molecular players involved. For instance, do orexin-B-activated OX1 receptors show a G-protein activation profile different from that of orexin-A-activated OX1 receptors?

In conclusion, the results presented here show that OX1 orexin receptor activation results in robust AA release. The inhibitor profile strongly suggests that this response is mediated by PLA2, and PLA2 thus seems to join the lipid signalling systems activated by orexin receptors, of which PLD and PLC and (indirectly) phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) have previously been identified (Lund et al., 2000; Randeva et al., 2001; Ammoun et al., 2006a; Johansson et al., 2008). The response occurs with a rather high potency, although not quite equal to the recently described PLD response (Johansson et al., 2008). Accordingly, the PLA2 pathway could be of high relevance for the orexin receptor signalling in many physiological settings, where the orexin peptide levels are low. Receptor-operated Ca2+ influx is required for the AA release, and AA release seems to enhance Ca2+ influx, constituting a positive feedback loop. Further experiments are required to confirm the identity of the AA-releasing enzymes and the relationship of this signalling to other lipid signalling systems engaged in orexin receptor signalling.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr Christophe Erneux (Free University of Brussels, Brussels, Belgium) for the pcDNA3-InsP3-5-phosphatase-I expression plasmid, and Karin Nygren and Pirjo Puroranta for technical assistance. This study was supported by the Academy of Finland, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation, the University of Helsinki Research Funds, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Swedish Research Council and Uppsala University.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AA

arachidonic acid

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GF109203X (bisindolylmaleimide I, Gö6850)

2-(1-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide

- IP3

inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3-5P1

type I IP3 5-phosphatase

- iPLA2

Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2

- Lp-PLA2

lipoprotein-associated PLA2

- MAFP

methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate

- NaBM

Na+-based medium

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PD 98059

2-(2-amino-3-methoxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PLD

phospholipase D

- probenecid

p-(dipropylsulphamoyl) benzoic acid; R-BEL, (R)-bromoenol lactone

- S-BEL

(S)-bromoenol lactone

- SB-334867

1-(2-methylbenzoxazol-6-yl)-3-(1,5)naphthyridin-4-yl-urea HCl

- SKF-96365

1-(β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]-4-methoxyphenethyl)-1H-imidazole HCl

- sPLA2

secreted phospholipase A2

- TEA

tetraethylammonium chloride

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- U0126

1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto)butadiene

References

- Akiba S, Sato T. Cellular function of calcium-independent phospholipase A2. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:1174–1178. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC) Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammoun S, Holmqvist T, Shariatmadari R, Oonk HB, Detheux M, Parmentier M, et al. Distinct recognition of OX1 and OX2 receptors by orexin peptides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:507–514. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammoun S, Johansson L, Ekholm ME, Holmqvist T, Danis AS, Korhonen L, et al. OX1 orexin receptors activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in CHO cells via multiple mechanisms: The role of Ca2+ influx in OX1 receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2006a;20:80–99. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammoun S, Lindholm D, Wootz H, Åkerman KE, Kukkonen JP. G-protein-coupled OX1 orexin/hcrtr-1 hypocretin receptors induce caspase-dependent and -independent cell death through p38 mitogen-/stress-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006b;281:834–842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsinde J, Balboa MA. Cellular regulation and proposed biological functions of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in activated cells. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1052–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S237–S242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800033-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Coste B, Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Phosphoinositide lipid second messengers: new paradigms for calcium channel modulation. Neuron. 2005;47:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt F, Missiaen L, Parys JB, Vanweyenberg V, De Smedt H, Erneux C. Isoprenylated human brain type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase controls Ca2+ oscillations induced by ATP in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17367–17375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm ME, Johansson L, Kukkonen JP. IP3-independent signalling of OX1 orexin/hypocretin receptors to Ca2+ influx and ERK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Tucker DE, Burchett SA, Leslie CC. Properties of the group IV phospholipase A2 family. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist T, Åkerman KEO, Kukkonen JP. Orexin signaling in recombinant neuron-like cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;526:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist T, Johansson L, Östman M, Ammoun S, Åkerman KE, Kukkonen JP. OX1 orexin receptors couple to adenylyl cyclase regulation via multiple mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6570–6579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CM, Wolf MJ, Mancuso DJ, Gross RW. Identification of the calmodulin-binding domain of recombinant calcium-independent phospholipase A2β. Implications for structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7129–7135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CM, Han X, Mancuso DJ, Gross RW. Identification of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) β, and not iPLA2γ, as the mediator of arginine vasopressin-induced arachidonic acid release in A-10 smooth muscle cells. Enantioselective mechanism-based discrimination of mammalian iPLA2s. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32807–32814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CM, Mancuso DJ, Yan W, Sims HF, Gibson B, Gross RW. Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48968–48975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Ekholm ME, Kukkonen JP. Regulation of OX1 orexin/hypocretin receptor-coupling to phospholipase C by Ca2+ influx. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:97–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Ekholm ME, Kukkonen JP. Multiple phospholipase activation by OX1 orexin/hypocretin receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1948–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8206-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Agonist-receptor efficacy. II. Agonist trafficking of receptor signals. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:232–238. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Ligand-selective receptor conformations revisited: the promise and the problem. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:346–354. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP. Regulation of receptor-coupling to (multiple) G-proteins. A challenge for basic research and drug discovery. Receptors Channels. 2004;10:167–183. doi: 10.3109/10606820490926151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP, Åkerman KEO. Orexin receptors couple to Ca2+ channels different from store-operated Ca2+ channels. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2017–2020. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP, Åkerman KEO. Intracellular signal pathways utilized by the hypocretin/orexin receptors. In: de Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, editors. Hypocretins as Integrators of Physiological Signals. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media; 2005. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP, Jansson CC, Åkerman KEO. Agonist trafficking of Gi/o-mediated alpha2A-adrenoceptor responses in HEL 92.1.7 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1477–1484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP, Holmqvist T, Ammoun S, Åkerman KE. Functions of the orexinergic/hypocretinergic system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1567–C1591. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00055.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KP, Peltonen HM, Bart G, Louhivuori LM, Penttonen A, Antikainen M, et al. Orexin-A-induced Ca2+ entry: evidence for involvement of trpc channels and protein kinase C regulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1771–1781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CC. Regulation of the specific release of arachidonic acid by cytosolic phospholipase A2. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund PE, Shariatmadari R, Uustare A, Detheux M, Parmentier M, Kukkonen JP, et al. The orexin OX1 receptor activates a novel Ca2+ influx pathway necessary for coupling to phospholipase C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30806–30812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meves H. Arachidonic acid and ion channels: an update. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:4–16. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milasta S, Evans NA, Ormiston L, Wilson S, Lefkowitz RJ, Milligan G. The sustainability of interactions between the orexin-1 receptor and beta-arrestin-2 is defined by a single C-terminal cluster of hydroxy amino acids and modulates the kinetics of ERK MAPK regulation. Biochem J. 2005;387:573–584. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier CM, Ghomashchi F, Lindsay MR, James S, Singer AG, Parton RG, et al. Arachidonic acid release from mammalian cells transfected with human groups IIA and X secreted phospholipase A2 occurs predominantly during the secretory process and with the involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25024–25038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näsman J, Bart G, Larsson K, Louhivuori L, Peltonen H, Åkerman KE. The orexin OX1 receptor regulates Ca2+ entry via diacylglycerol-activated channels in differentiated neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10658–10666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2609-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randeva HS, Karteris E, Grammatopoulos D, Hillhouse EW. Expression of orexin-A and functional orexin type 2 receptors in the human adult adrenals: implications for adrenal function and energy homeostasis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4808–4813. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaloske RH, Dennis EA. The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1246–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Angiotensin II-stimulated signaling through G proteins and beta-arrestin. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:cm14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3112005cm14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL, Mignen O. ARC channels: a novel pathway for receptor-activated calcium entry. Physiology. 2004;19:355–361. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00018.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Sabido-David C, Brough SJ, Jewitt F, Johns A, Porter RA, et al. SB-334867-A: the first selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1179–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski A, Nelson JJ, Hegg L, Macphee C. Lp-PLA2: a new kid on the block. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1645–1650. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.070672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]