Abstract

The important roles of a nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) are widely accepted in various biological processes as well as metabolic diseases. Despite the worldwide quest for pharmaceutical manipulation of PPARγ activity through the ligand-binding domain, very little information about the activation mechanism of the N-terminal activation function-1 (AF-1) domain. Here, we demonstrate the molecular and structural basis of the phosphorylation-dependent regulation of PPARγ activity by a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, Pin1. Pin1 interacts with the phosphorylated AF-1 domain, thereby inhibiting the polyubiquitination of PPARγ. The interaction and inhibition are dependent upon the WW domain of Pin1 but are independent of peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans-isomerase activity. Gene knockdown experiments revealed that Pin1 inhibits the PPARγ-dependent gene expression in THP-1 macrophage-like cells. Thus, our results suggest that Pin1 regulates macrophage function through the direct binding to the phosphorylated AF-1 domain of PPARγ.

Keywords: Diseases/Metabolic, Metabolism/Metabolic Syndrome, Protein/Protein-Protein Interactions, Receptors/Modification, Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases/Serine/Threonine, Transcription, Nuclear Receptor, Ubiquitination

Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ; NR1C3)3 is a key regulator of adipocyte differentiation, glucose homeostasis, and macrophage function (1, 2). Alternative promoter utilization generates two major PPARγ isoforms: a shorter isoform, PPARγ1, is widely distributed, whereas PPARγ2 is restricted to adipose tissues (3). PPARγ ligands act on the ligand-binding domain and induce conformational changes to recruit coactivators (4, 5). On the other hand, PPARγ activity is also regulated by the phosphorylation of its ligand-independent activation function-1 (AF-1) domain. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase reportedly phosphorylate Ser84 in the AF-1 domain of PPARγ1 (6, 7). Ser84 of human PPARγ1 corresponds to Ser112 in human and mouse PPARγ2, and hereafter, we will refer to this residue by its numbering in human PPARγ1. In mice, prevention of Ser84 phosphorylation by mutating Ser84 to alanine increases the insulin sensitivity, suggesting the enhancement of PPARγ function (8). In humans, the P85Q mutation was observed in German obese subjects with a high body mass index (9) or with severe insulin resistance (10). This mutation may affect the phosphorylation status of Ser84, immediately preceding the mutated residue. Thus, the phosphorylation of the AF-1 domain has functional significance in PPARγ-mediated gene regulation, but the molecular mechanism remains obscure.

In this study, we examined the mechanism of phosphorylation-dependent regulation of PPARγ and revealed that the phosphorylated AF-1 domain targets only the WW domain of peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans-isomerase (PPIase), Pin1, and was not a substrate for the PPIase of Pin1. The direct binding of Pin1 to the AF-1 domain resulted in inhibiting the polyubiquitination and the transcriptional activity of PPARγ revealed by overexpression and knockdown experiments using cell lines. Data presented here suggest that the phosphorylation-dependent regulation of PPARγ activity is mediated by the direct binding to Pin1 without proline isomerization.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Wako) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin mix (Nacalai Tesque). Cells were transfected by the calcium-phosphate method with a CellPhect transfection kit (GE Healthcare). HEK293P cells were maintained in the same manner as HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected by GeneJuice transfection reagent (Takara Bio) for packaging the retrovirus. THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin mix (Nacalai Tesque).

Coimmunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

Transiently transfected cells plated on 60-mm dishes were harvested with 350 μl of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-Hcl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 50 mm NaF, 100 μm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque)). After centrifugation, the lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 agarose affinity Gel (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h. After the incubation, the beads were washed 5× with 1-ml aliquots of lysis buffer. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-FLAG M2-peroxidase (Sigma) or anti-hemagglutinin (HA)-peroxidase, high affinity (3F10) (Roche). Chemiluminescence was detected with ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagents and Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

Purification of Recombinant Pin1

Human Pin1 and its mutant forms were cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 expression plasmid (GE Healthcare). The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Novagen). The cells were grown in LB medium with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C to an A600 of 0.7–0.8. The expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mm, and the cells were further incubated for 16 h at 18 °C. Cells from a 1-liter culture were harvested and resuspended in 100 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were sonicated, and the soluble fraction was isolated by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatants were applied to phosphate-buffered saline-equilibrated glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). After a thorough wash with phosphate-buffered saline, the fusion proteins were eluted with 80 ml of 10 mm reduced glutathione in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0/100 mm NaCl. The collected proteins were cleaved with thrombin protease at 4 °C for 12 ∼ 15 h during dialysis against 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0/1 mm TCEP. The digested solution was passed through a 5-ml HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare). The flow through was collected and concentrated to 7 ml, using a 30,000 molecular weight cut-off Amicon Ultra 15 centrifugal concentrator. The sample was fractionated on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 prep grade column (GE Healthcare), and the appropriate fractions were concentrated using a 10,000 molecular weight cut-off Amicon Ultra 15 centrifugal concentrator. The protein sample was frozen at −80 °C until use.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis

SPR measurements were performed using Biacore 2000 at 24 °C. The synthetic, biotinylated PPARγ1 AF-1 peptides were immobilized on the Sensor chip SA (Biacore). Both the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides were immobilized on the same chip in different lanes. Experiments were performed by injecting the wild type recombinant Pin1 or its mutants at a flow rate of 50 μl/min. Binding was measured in the following order: blank, the nonphosphorylated peptide, and the phosphorylated peptide.

NMR Spectra Acquisition

The standard set of triple resonance experiments, including HNCO, HNCOCA, HNCA, HNCACB, and CBCA(CO)NH, was performed to obtain the backbone 1H, 15N, 13CA, 13CB, and 13C′ resonance assignments for human Pin1 under the present experimental conditions (11); the protein was dissolved in a buffer solution containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 0.1 mm pefabloc, and all of the NMR spectra were collected at 293 K. All NMR experiments were performed with a Bruker DMX-600 spectrometer equipped with shielded XYZ gradients. NMR data were processed by the program NMRPipe (12). The programs NMRView version 5.0.4 (B.A. Johnson, Merck Research Laboratories) and Smart Notebook (13) were used for the resonance assignment. The Pin1 protein used in these experiments contained all 163 residues of the native protein, with 20 additional residues from the expression vector pET-28a; the His6 tag was not cleaved in the present NMR experiments.

Luciferase Assay

The cell-based transcription assay was described previously (14). In this study, we used HEK293T cells instead of COS-7 cells. Transient transfections of reporter genes were performed by using CellPhect (GE Healthcare). Data are represented as mean ± S.D.

Flow Cytometry

THP-1 cells were detached from dishes by a treatment with 1 mm EDTA/phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were first treated with mouse BD Fc Block (BD Bioscience Pharmingen) and then were treated with an fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD36 antibody (MCA772F, Serotec Ltd.). Fluorescent intensities of individual cells were analyzed by using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Knockdown Experiments with Short Hairpin (sh) RNA Expression by a Retrovirus

The procedure for the retrovirus preparation was described previously (15). The sequences used for PPARγ knockdown were: shPPARγ599, gatccccGCTTATCTATGACAGATGTGATCTTttcaagagaAAGATCACATCTGTCATAGATAAGCttttta and shPPARγ1210, gatccccGCTTCATGACAAGGGAGTTTCTAAAttcaagagaTTTAGAAACTCCCTTGTCATGAAGCttttta. (Capital letters indicate the target sequences for the human PPARγ mRNA.) The DNA sequence used for Pin1 knockdown was shPin1, gatccccGAGACCTGGGTGCCTTCAGCA ttcaagagaTGCTGAAGGCACCCAGGTCTCttttta. These oligonucleotide DNAs were cloned into pSUPER.puro (OligoEngine).

RESULTS

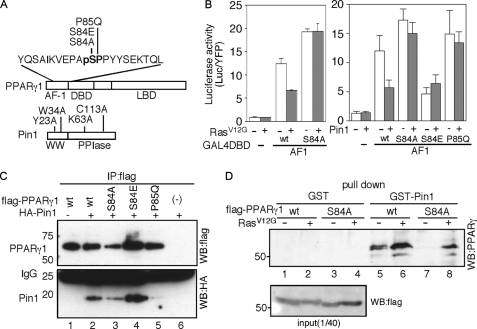

Due to the overlapped recognition sequences between the proline-directed kinases and Pin1 (16), we investigated the possibility of the Pin1-mediated regulation of AF-1 activity. Coexpression of the constitutively active form of the Ras protein (RasV12G), to induce the phosphorylation of PPARγ through the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, inhibited AF-1 activity, but the S84A mutation in the AF-1 domain abolished the inhibitory effects of RasV12G (Fig. 1B, left panel). Coexpression of Pin1 reduced AF-1 activity, but not significantly, in the S84A, S84E, and S85Q mutants (Fig. 1B, right panel). We then analyzed the interaction between Pin1 and the AF-1 domain of PPARγ by coimmunoprecipitation. The interaction of Pin1 with PPARγ was observed for the wild type (Fig. 1C, lane 2) but not for the P85Q mutatnt (Fig. 1C, lane 5). The amount of Pin1 copurified with PPARγ was reduced by the S84A mutation (Fig. 1C, lane 3). Another PPARγ mutant, S84E, which mimics the phosphorylated state of the AF-1 domain, displayed significant affinity for Pin1 (Fig. 1C, lane 4). Using a recombinant GST-Pin1 protein, we observed the enhancement of the interaction between GST-Pin1 and PPARγ by the coexpression of RasV12G (Fig. 1D, lanes 5 and 6). By contrast, the S84A mutation completely inhibited the binding (Fig. 1D, lane 7). Thus, we concluded that the phosphorylation of the AF-1 domain induces the binding of Pin1 to PPARγ, which concomitantly inhibits the transcriptional activity. However, we noticed that the interaction was slightly retained in the presence of RasV12G (Fig. 1D, lane 8). In addition to Ser84, there are two other possible phosphorylation sites by proline-directed kinases at Ser245 and Thr268 in the PPARγ ligand-binding domain. In fact, slower migration of the PPARγ protein was still observed in the S84A mutant coexpressed with RasV12G (Fig. 1D, lower panel). Although we do not have direct evidence for the phosphorylation of these residues, we do not exclude the possibility that Pin1 also interacts with the ligand-binding domain in addition to the AF-1 domain.

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylation-dependent binding of Pin1 to the AF-1 domain of PPARγ. A, schematic representation of the domain structures of PPARγ and Pin1. The amino acid sequence indicates the AF-1 peptide sequence used for in vitro experiments in this study. The mutated residues in PPARγ are denoted above the sequence. Bold letters indicate the recognition motif of Pin1, in which pS denotes the phosphorylated serine. B, effects of coexpression of RasV12G or Pin1 on the intrinsic activity of the AF-1 domain. GAL4-fused AF-1 domains with the indicated mutations were transfected with or without RasV12G or Pin1 (left and right panels, respectively). Data are presented as the means ± S.D. DBD, DNA-binding domain. C, coimmunoprecipitation of Pin1 with full-length PPARγ in HEK293T cells. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were analyzed by Western blots (WB) probed with either an anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibody (WB:flag and WB:HA, respectively). D, Pin1 interacts with PPARγ in vitro. The cell lysate was incubated with GST or GST-Pin1, and the interaction between Pin1 and PPARγ was detected by Western blotting, using an anti-PPARγ antibody. Cell lysates were also probed with anti-FLAG antibody. LBD, ligand-binding domain.

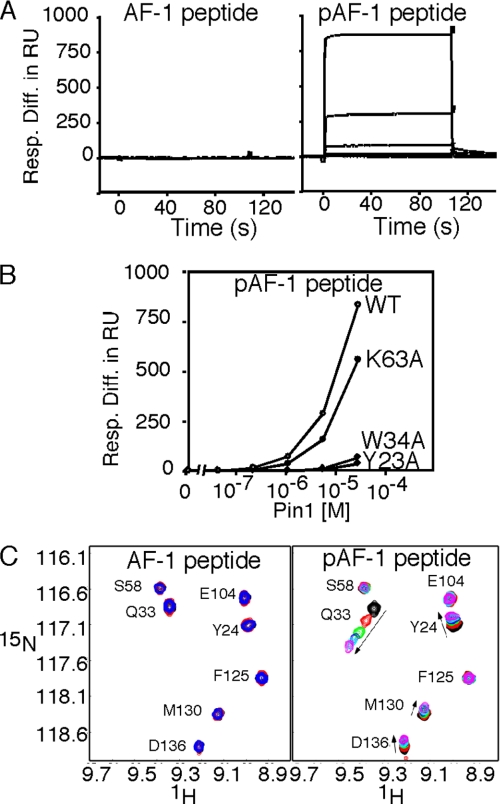

Further characterization of the interaction, using SPR, revealed that the phosphorylated AF-1 (pAF-1) peptide but not the nonphosphorylated (AF-1) peptide, was specifically bound to Pin1 in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 2A). The Pin1 WW domain, classified as group IV, preferentially binds to the phosphorylated serine/threonine-proline residues, while the PPIase domain catalyzes the isomerization of the pSer/Thr-Pro segment in the target protein (16). The mutations of Y23A or W34A in the WW domain and K63A in the PPIase domain (Fig. 1A) abolished the binding activity to the phospho-peptides and the PPIase activity of Pin1, respectively (17). The K63A mutation within the PPIase domain only slightly reduced the binding (Fig. 2B). By contrast, the W34A or Y23A mutation within the WW domain completely abolished the interaction. In agreement with the SPR experiments, NMR titration measurements revealed that the pAF-1 peptide mainly induced chemical shift perturbations in the WW domain, whereas the nonphosphorylated counterpart caused no significant spectral change (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. S1). A conventional PPIase assay (see supplemental “Experimental Procedures”) revealed that an excess amount of either AF-1 or the pAF-1 peptide did not inhibit the Pin1-induced isomerization of the substrate peptide (supplemental Fig. S2). Thus, we concluded that the pAF-1 peptide is not a substrate for the PPIase activity of Pin1.

FIGURE 2.

Phosphorylation-dependent binding of Pin1 to the AF-1 peptide of PPARγ. A, SPR analyses of the interaction between Pin1 and the AF-1 peptide. Traces of the titration of Pin1 on sensor chips immobilized with the non-phosphorylated (AF-1) and phosphorylated AF-1 (pAF-1) peptide (left and right panels, respectively). Concentrations of analyte were 0, 0.04, 0.2, 1, 5, and 25 μm. Data are presented as the response difference in resonance units. B, concentration dependence of the interaction between Pin1 and pAF-1, plotted for each Pin1 protein with the indicated mutation. C, overlay of part of the amide region of the 1H-15N heteronuclear-single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra for Pin1 with various amounts of pAF-1 peptide. In the spectra for the pAF-1 titration to Pin1, the overlaid spectra were collected for samples with pAF-1 to Pin1 ratios of 0.0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, and 1.3. The corresponding spectra for the nonphosphorylated AF-1 with Pin1 and with AF-1 to Pin1 ratios of 0.0, 0.40, and 1.12, are displayed. WT, wild type.

We noticed a PPxY motif immediately after the Pin1-recognition motif. The PPxY motif is recognized by several ubiquitin ligases containing a group I WW domain. Then, we determined the possible cross-talk between phosphorylation and polyubiquitination of the PPARγ protein through Pin1 binding. We found that the polyubiquitination of PPARγ in the absence of ligands was inhibited by coexpressed Pin1 (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 and 8). The Y23A mutant of Pin1 lost the ability to inhibit polyubiquitination, whereas the K63A mutation retained it (Fig. 3A, lanes 9 and 10, respectively). Pin1-mediated inhibition of polyubiquitination was not observed in PPARγ lacking the AF-1 domain (Fig. 3A, lanes 11 and 12). The polyubiquitination of PPARγ was also inhibited by the Pin1 C113A mutant and the WW domain alone but not by the PPIase domain alone (Fig. 3B, lanes 4, 5, and 6, respectively). Pin1-mediated inhibition of polyubiquitination was also observed even in the presence of a proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that Pin1 regulates the ubiquitination step, rather than the degradation step. Collectively, these results indicated that the inhibition of the PPARγ polyubiquitination by Pin1 requires the interaction between the WW domain and the AF-1 domain, whereas PPIase activity is not essential.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of polyubiquitination of PPARγ by Pin1. A, Pin1 inhibits the polyubiquitination of PPARγ in a WW domain-dependent manner. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were analyzed by Western blot (WB) probed with an anti-HA antibody to detect polyubiquitination (bottom panel, WB:HA). Cell lysates were also probed with an anti-FLAG or anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (top panel, WB:flag and WB:GFP, respectively). B, Pin1 inhibits the polyubiquitination of PPARγ in a WW domain-dependent manner. Experimental condition was same as A. C, effects of proteasome inhibitor, MG132, on the polyubiquitination of PPARγ. Cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 for 5 h before harvest. Immunoprecipitation condition was the same as in A. wt, wild type; Ub, ubiquitin.

To explore the physiological importance of the Pin1-PPARγ interaction, we investigated the involvement of Pin1 in the PPARγ-mediated activation of macrophage function. Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) is one of the target genes of PPARγ in macrophage cells (18), and it has strong connections with the development of metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis (19). The PPAR-response element (PPRE) for the mouse Fabp4 gene has been extensively analyzed (20), but that of the human FABP4 gene has not. Therefore, we analyzed the human FAPB4 promoter and found that one PPRE is located at −5216 bp (Fig. 4A). To investigate the function of the PPRE at −5216 bp, we made a series of deletion and mutation constructs of the FABP4 5′ upstream region (Fig. 4A). PPARγ-dependent activation of the FABP4 promoter was totally dependent on the PPRE sequence (Fig. 4B). A highly conserved sequence around this PPRE among mammals suggests that this region is involved in the PPARγ-dependent regulation of FABP4 expression. Pin1 inhibited the PPARγ-activated human FABP4 promoter in both the presence and absence of a synthetic PPARγ agonist, BRL49653 (Fig. 4C). Ubiquitin-dependent degradation is required for efficient transactivation by nuclear receptors (21), and therefore, Pin1 might inhibit the PPARγ activity by inhibiting the receptor turnover. In fact, a proteasome inhibitor, MG132, reduced the activity of PPARγ (Fig. 4D). Pin1 mutation in the WW domain such as Y23A and W34A abolished the inhibitory effect of Pin1 on the PPARγ-dependent transcription (Fig. 4E). On the contrary, mutations in the PPIase domain such as K63A and C113A showed the same inhibitory effect on PPARγ as the wild type (Fig. 4E), suggesting that the Pin1-mediated regulation of PPARγ is dependent on the WW domain rather than PPIase activity. We next examined the effects of Pin1 knockdown on the expression of the endogenous PPARγ-regulated proteins. The efficiency of the knockdown by short hairpin RNA expression were determined by Western blot and RT-PCR (supplemental Fig. S3). In THP-1 macrophage-like cells differentiated by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate treatment, the PPARγ agonist increased the expression of FABP4 and another PPARγ-target gene, heme oxygenase-1 (22) (Fig. 4F, lanes 1 and 2). The expression levels of both the FABP4 and HO-1 proteins were decreased in the PPARγ knockdown cells (Fig. 4F, lanes 3–6), indicating that both proteins are regulated by PPARγ. On the other hand, the knockdown of Pin1 augmented the expression of these proteins by PPARγ (Fig. 4F, lanes 7 and 8). Therefore, we concluded that Pin1 reduces the activity of PPARγ in THP-1 cells. Lastly, we analyzed the expression of CD36, which is one of the surface markers for activated macrophages in atherosclerosis (23). The PPARγ knockdown abolished the agonist-induced up-regulation of CD36 (Fig. 4G, middle). In contrast, the Pin1 knockdown increased the basal level of CD36 and also sensitized the induction against the addition of the PPARγ agonist (Fig. 4G, right). Thus, we concluded that Pin1 modulates macrophage activation through an interaction with PPARγ.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibitory effect of Pin1 on PPARγ-dependent transcription. A, schematic representation of the human FABP4 5′ upstream region and a series of DNA constructs used for the reporter assay. PPRE was found at −5216 bp (arrowhead) within the mammalian conserved region. The figure was drawn using the ENCODE web server. B, PPARγ-dependent activation of the human FABP4 enhancer. The indicated reporter plasmids, PPARγ1 and RXRα genes were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and the transcriptional activities were determined by the luciferase activity in the presence or absence of 0.5 μm BRL49653. C, effect of Pin1 on the PPARγ-dependent activation of the FABP4 promoter. The indicated reporter plasmids, PPARγ1 and RXRα genes were cotransfected into HEK293T cells with or without Pin1. D, effects of Pin1 mutations on the Pin1-mediated inhibition of the PPARγ-dependent transcription. The indicated reporter plasmids, PPARγ1 and RXRα genes were cotransfected into HEK293T cells with or without Pin1 carrying indicated mutations. E, effects of MG132 on the PPARγ-dependent transcription. The indicated reporter plasmids and PPARγ1 and RXRα genes were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. After 12 h, cells were treated with or without 10 μm MG132 for another 6 h. Luciferase activity was not normalized by any internal control because MG132 might change the stability of the control protein. F, effect of the Pin1 knockdown on the PPARγ-dependent up-regulation of endogenous proteins in THP-1 cells. Cells were differentiated into macrophage-like cells by 5 nm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. After 24 h, cells were treated with 0.5 μm BRL49653 for additional 24 h. Cellular lysates including 50 μg proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and protein expression was analyzed by Western blots probed with either an anti-FABP4, anti-HO-1 or anti-β-Tubulin antibody. G, fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of the effect of the Pin1 knockdown on the PPARγ-dependent CD36 expression in THP-1 cells. Cells were differentiated into macrophage-like cells by 5 nm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. After 24 h, cells were treated with 0.5 μm BRL49653 for additional 24 h. 0.5 × 106 cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CD36 antibody, and the fluorescent intensity was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter. wt, wild type; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

DISCUSSION

It was reported that the two domains of Pin1 both target to the same phosphorylated serine/threonine-proline sequence (16). However, we found that the phospho-AF-1 domain in PPARγ was recognized by the WW domain but not the PPIase domain of Pin1. These results allow us to propose that Pin1 affects the function of PPARγ through the interaction between the AF-1 region of PPARγ and the WW domain in Pin1, rather than the proline isomerization by the PPIase domain.

Among the many reports about the interaction between Pin1 and phosphorylated proteins, several studies described the distinct usage of two domains for regulation of the target proteins (24, 25) in agreement with our results. For example, Pin1 promotes the Stat3 transcriptional activity in a Ser727 phosphorylation-dependent manner. However, the WW domain mutation (Y23A) but not the catalytic domain mutations abolished this effect (24), suggesting that the PPIase activity is dispensable for transcriptional activation. In the case of the Tau protein, both the phosphorylated Thr212 and phosphorylated Thr231 sites are recognized by the WW domain of Pin1, but only the phosphorylated Thr212–Pro bond is isomerized by the PPIase domain (25), suggesting that the phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro is not always a substrate for PPIase activity.

How does Pin1 affect the function of PPARγ independently of its catalytic activity? The AF-1 sequence, adjacent to the Pin1 target motif, overlaps with a motif (PPxY) for the group I WW domain (26). The binding of Pin1 to the pSer-Pro sequence, sterically blocks the PPxY sequence, thereby prohibiting the binding of a protein harboring the group I WW domains. Interestingly, the Nedd4 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases contains several group I WW domains (27), and thus, it is possible that the interaction with Pin1 is involved in the regulation of the polyubiquitination-mediated PPARγ degradation, in a “binary switch” manner (Fig. 5). Such competition may not be observed in other PPARs, because they lack the motif for the group I WW domain near the phosphorylation site. Therefore, it will be interesting to determine whether this difference between the subtypes is connected with the AF-1-mediated isotype-selective regulation of gene expression (28). Identification of the physiological ubiquitin ligase for PPARγ will greatly advance our understanding for the regulation of the PPARγ activity.

FIGURE 5.

Model of the Pin1-mediated regulation of PPARγ activity. Binary switch model of the Pin1-mediated regulation of PPARγ. In the absence of phosphorylation signals, PPARγ is polyubiquitinated. Ras-mediated kinase signals induce the phosphorylation of Ser84. Binding of Pin1 to the phosphorylated AF-1 prevents the polyubiquitination of PPARγ, resulting in slow turnover of the PPARγ protein. Because the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, reduces PPARγ activity, the efficient transcription seems to require continuous turnover of PPARγ through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Then, Pin1-mediated inhibition of polyubiquitination results in the reduction of the PPARγ activity. In this regulation, binding through the WW domain is sufficient for the inhibition of polyubiquitination, and the PPIase activity of Pin1 is dispensable. LBD, ligand-binding domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; (Ub)n, polyubiquitination.

In this study, we showed that Pin1-mediated negative regulation of PPARγ has an important role for macrophage function. FABP4 is one of the most important downstream targets among many PPARγ-regulated genes, because FABP4 in macrophages is involved in atherosclerosis (19). In the future, it is important to investigate the possible involvement of Pin1 in atherosclerosis. There are several Pin1-targeted drugs, but most of them bind to the PPIase domain of Pin1 (29, 30). To manipulate the Pin1-mediated regulation of PPARγ, the WW domain, rather than the PPIase domain, must be targeted by drugs. Structural information provided by our NMR study will help the design and screening of such novel Pin1 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hiroto Yamaguchi, Takuji Oyama, and Akira Kakizuka for helpful comments and Ms. Kanako Maebara and Ms. Sayaka Shiki for technical support. We also thank Drs. Kozo Tanaka and Akihiko Muto for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a donation from Takara Bio, Inc. and by a Grant-in-aid for Creative Scientific Research Program (18GS0316) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Equations 1–4, additional references, and Figs. S1–S3.

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PPIase

- peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans-isomerase

- AF-1

- activation function-1

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- PPRE

- PPAR response element

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- sh

- short hairpin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee C. H., Olson P., Evans R. M. (2003) Endocrinology 144, 2201–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen E. D., Spiegelman B. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37731–37734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee R., Jow L., Croston G. E., Paterniti J. R., Jr. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8071–8076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waku T, Shiraki T, Oyama T, Fujimoto Y, Maebara K, Kamiya N, Jingami H, Morikawa K. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 385, 188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 121–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams M., Reginato M. J., Shao D., Lazar M. A., Chatterjee V. K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5128–5132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu E., Kim J. B., Sarraf P., Spiegelman B. M. (1996) Science 274, 2100–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangwala S. M., Rhoades B., Shapiro J. S., Rich A. S., Kim J. K., Shulman G. I., Kaestner K. H., Lazar M. A. (2003) Dev. Cell 5, 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ristow M., Müller-Wieland D., Pfeiffer A., Krone W., Kahn C. R. (1998) New Eng. J. Med. 339, 953–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blüher M., Paschke R. (2003) Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 111, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanagh J., Fairbrother W. J., Palmer A. G., III, Skelton N. J. (1996) Protein NMR, pp. 410–531, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slupsky C. M., Boyko R. F., Booth V. K., Sykes B. D. (2003) J. Biomol. NMR 27, 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiraki T., Kamiya N., Shiki S., Kodama T. S., Kakizuka A., Jingami H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14145–14153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikura T., Tashiro S., Kakino A., Shima H., Jacob N., Amunugama R., Yoder K., Izumi S., Kuraoka I., Tanaka K., Kimura H., Ikura M., Nishikubo S., Ito T., Muto A., Miyagawa K., Takeda S., Fishel R., Igarashi K., Kamiya K. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 7028–7040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu K. P., Zhou X. Z. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 904–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryo A., Suizu F., Yoshida Y., Perrem K., Liou Y. C., Wulf G., Rottapel R., Yamaoka S., Lu K. P. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 1413–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelton P. D., Zhou L., Demarest K. T., Burris T. P. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 261, 456–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furuhashi M., Tuncman G., Görgün C. Z., Makowski L., Atsumi G., Vaillancourt E., Kono K., Babaev V. R., Fazio S., Linton M. F., Sulsky R., Robl J. A., Parker R. A., Hotamisligil G. S. (2007) Nature 447, 959–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rival Y., Stennevin A., Puech L., Rouquette A., Cathala C., Lestienne F., Dupont-Passelaigue E., Patoiseau J. F., Wurch T., Junquéro D. (2004) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 311, 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lonard D. M., Nawaz Z., Smith C. L., O'Malley B. W. (2000) Mol. Cell 5, 939–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krönke G., Kadl A., Ikonomu E., Blüml S., Fürnkranz A., Sarembock I. J., Bochkov V. N., Exner M., Binder B. R., Leitinger N. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 1276–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tontonoz P., Nagy L., Alvarez J. G., Thomazy V. A., Evans R. M. (1998) Cell 93, 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lufei C., Koh T. H., Uchida T., Cao X. (2007) Oncogene 26, 7656–7664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smet C., Wieruszeski J. M., Buée L., Landrieu I., Lippens G. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 4159–4164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otte L., Wiedemann U., Schlegel B., Pires J. R., Beyermann M., Schmieder P., Krause G., Volkmer-Engert R., Schneider-Mergener J., Oschkinat H. (2003) Protein Sci. 12, 491–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingham R. J., Gish G., Pawson T. (2004) Oncogene 23, 1972–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hummasti S., Tontonoz P. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1261–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Daum S., Wildemann D., Zhou X. Z., Verdecia M. A., Bowman M. E., Lücke C., Hunter T., Lu K. P., Fischer G., Noel J. P. (2007) ACS Chem. Biol. 2, 320–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegrist R., Zürcher M., Baumgartner C., Seiler P., Diederich F. (2007) Helvetica Chimica Acta 90, 217–237 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.