Abstract

NADPH oxidase comprises both cytosolic and membrane-bound subunits, which, when assembled and activated, initiate the transfer of electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen to form superoxide. This activity, known as the respiratory burst, is extremely important in the innate immune response as indicated by the disorder chronic granulomatous disease. The regulation of this enzyme complex involves protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions as well as phosphorylation events. Previously, our laboratory demonstrated that the small membrane subunit of the oxidase complex, p22phox, is phosphorylated in neutrophils and that its phosphorylation correlates with NADPH oxidase activity. In this study, we utilized site-directed mutagenesis in a Chinese hamster ovarian cell system to determine the phosphorylation sites within p22phox. We also explored the mechanism by which p22phox phosphorylation affects NADPH oxidase activity. We found that mutation of threonine 147 to alanine inhibited superoxide production in vivo by more than 70%. This mutation also blocked phosphorylation of p22phox in vitro by both protein kinase C-α and -δ. Moreover, this mutation blocked the p22phox-p47phox interaction in intact cells. When phosphorylation was mimicked in vivo through mutation of Thr-147 to an aspartyl residue, NADPH oxidase activity was recovered, and the p22phox-p47phox interaction in the membrane was restored. Maturation of gp91phox was not affected by the alanine mutation, and phosphorylation of the cytosolic component p47phox still occurred. This study directly implicates threonine 147 of p22phox as a critical residue for efficient NADPH oxidase complex formation and resultant enzyme activity.

Keywords: Phorbol Esters, Protein Kinase C (PKC), Protein Palmitoylation, Protein-Protein Interactions, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Respiratory Burst, NADPH Oxidase

Introduction

Killing of microorganisms by the innate immune response involves phagocytic white blood cells as the first line of defense (1–3). These cells utilize both oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent tactics to destroy pathogens and fight infections (1, 4–6). The oxygen-dependent form of killing is known as the respiratory burst. This respiratory burst results from the reduction of molecular oxygen to superoxide, the parent molecule to many other toxic oxygen species (7, 8). This burst is mediated by a multimeric enzyme complex known as NADPH oxidase. This complex consists of the membrane-bound flavocytochrome b558 as well as cytosolic components p47phox,3 p67phox, p40phox, and the small GTP-binding protein Rac (9). Flavocytochrome b558 contains all of the electron transport machinery, including binding sites for NADPH and FAD as well as two hemes (10–14). Upon activation, the cytosolic components translocate to the membrane and bind the flavocytochrome, resulting in a favorable conformation for electron flow to occur (15).

Dysregulation of superoxide production can exacerbate many diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer disease, and many others (16–20). Defects in the respiratory burst can also lead to problems in host defense, as illustrated by the lack of superoxide-dependent killing in chronic granulomatous disease (21, 22). As a result, NADPH oxidase activation is tightly regulated by phosphorylation events as well as protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions (23–28). When phagocytes encounter pathogens, numerous signaling cascades are activated, including G proteins, phospholipases, lipid second messengers, calcium release, and protein kinases, leading to the formation of a functional NADPH oxidase (2). The activity of protein kinases within this regulation has been extensively studied (28, 29). The protein kinase C (PKC) family of enzymes has been implicated in NADPH oxidase activation (30–35). They can be activated by calcium and lipids resulting from phospholipase activity triggered by agonists such as opsonized particles and bacterial peptides or directly by the PKC agonist phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (2, 36–38). This activation results in the phosphorylation of almost all of the oxidase components. Phosphorylation has been shown to have important functional roles such as the release of p47phox from its autoinhibitory state (39). We hypothesize that phosphorylation of specific residues of another component, p22phox, by PKC is important for optimal NADPH oxidase function.

p22phox mRNA is abundant in most cell lines and tissues of the body (40, 41). Among cell lines, COS and HEK293 cells have been widely used to study NADPH oxidase. Although these cell lines are readily transfected, previous studies to examine the structure/function of p22phox have predominantly relied on p22phox overexpression systems (42–44). Recently, Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells were discovered to have no endogenous p22phox expression (45). We have developed a cell system to take advantage of this trait of CHO cells to study the effects of mutations in p22phox on NADPH oxidase activity (46). In this study, we have characterized the NADPH oxidase response to PMA in this system. We determined that PMA-dependent p22phox phosphorylation occurs on threonine 147 and that blocking this phosphorylation reduces superoxide production as well as interferes with the p22phox-p47phox interaction in the membrane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Hanks' balanced salt solution was obtained from Invitrogen. PMA and leupeptin were from Alexis Biochemicals. 1,2-Didecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate and 1-oleoyl-2-acetoyl-sn-glycerol were obtained from Avanti® Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Primary antibodies 54.1 (anti-gp91phox) and 44.1 (anti-p22phox) were generously donated by Dr. Algirdas Jesaitis of Montana State University (Bozeman, MT) (47). Anti-p47phox and anti-p67phox antibodies (made in goat) were generously donated by Dr. Tom Leto of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) (48). Alternate p47phox antibodies (sc-14015, rb; sc-17845, ms) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (mouse, rabbit, goat) immunoglobulin G (IgG) were obtained from Pierce. PerkinElmer Life Sciences provided the [γ-32P]ATP (2 mCi/ml).

Cell Lines

CHO K1 cell lines stably transfected with oxidase components were constructed as described previously (46). Cells were maintained in F12K medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (Hyclone), 0.15% sodium bicarbonate, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). CHO cells expressing gp91phox, p47phox, and p67phox (CHO 91/47/67) were selected using 1 mg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem) and 0.2 mg/ml hygromycin (Calbiochem). CHO cells expressing gp91phox, p47phox, p67phox, and p22phox (CHOphox) were grown in the presence of 1 mg/ml puromycin, 0.2 mg/ml hygromycin, and 1.8 mg/ml neomycin (Calbiochem). Cells were subcultured every 3–4 days.

p22phox Mutant Construction

Mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) containing wild type p22phox was a kind gift from R. S. Arnold (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) (42). Primers used for p22phox mutant production were as follows: P156Q forward, 5′-ccgcccagcaacccccagccgcggcccccggcc-3′, and reverse, 5′-ggccgggggccgcggctgggggttgctgggcgg-3′; T132A forward, 5′-gtgcgtggcgagcagtgggcgcccatcgagcccaag- 3′, and reverse, 5′-cttgggctcgatgggcgcccactgctcgccacgcac-3′; T147A forward, 5′-ccgggagcggccgcagatcggaggcgccatc-3′, and reverse, 5′-gatggcgcctccgatctgcggccgctcccgg-3′; T147D forward, 5′-ccgggagcggccgcagatcggaggcgacatc-3′, and reverse, 5′-gatgtcgcctccgatctgcggccgctcccgg-3′. Mutants were made using the PfuUltra® high fidelity DNA polymerase kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer's instructions. Following transformation into Escherichia coli, plasmid DNA was isolated from bacteria using standard techniques. Mutations were verified by sequencing at the Biomolecular Research Laboratory DNA Sequencing Core laboratory at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

CHO 91/47/67 p22phox Transfection

Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. CHO 91/47/67 cells were plated at 1.2–1.5 × 106/60-mm cell culture dish (Corning) in antibiotic-free F12K medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated bovine growth serum and 0.15% sodium bicarbonate and incubated overnight (∼16 h). Following cell adhesion, 10 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 30 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in serum-free medium (F12K), incubated for 20 min, and added to medium containing 20% bovine growth serum for a final concentration of 10% bovine growth serum before addition to the cells. After 24 h, transfected cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed, and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution/glucose (5 mm) at 1 × 107 cells/ml.

Chemiluminescence

NADPH oxidase activity in intact cells was monitored by chemiluminescence. Isolated CHO cells (1 × 107 cells/ml) in Hanks' balanced salt solution/glucose were diluted to 2.5× the indicated final concentrations in Hanks' balanced salt solution/glucose + 0.1% gelatin (Sigma) and then incubated with 100 μl of Diogenes (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA) in a white 96-well plate (Greiner, Lake Mary, FL). PMA was added at the indicated concentrations for a final volume of 250 μl/reaction. Light emission was monitored continuously in duplicate or triplicate wells/condition at 25 °C for 1–2 h in a MicroLumat Plus LB 96 V luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN). Data are expressed as relative light units per min (RLU/min) calculated from the slope between ∼20 and 40 min after stimulation unless otherwise specified.

Protein Preparation

Whole cell lysates were prepared at 1 × 107 cell equivalents/ml in Laemmli sample buffer then boiled for 10 min. Cell membrane protein was obtained after disruption by sonication as described previously (49) with modifications. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml of sonication buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 11% sucrose, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm EGTA, 25 mm NaF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), sonicated 7 × 3 s (20% output power, model W-220; Heat Systems Ultrasonics), then centrifuged (1950 rpm (870 × g), 5 min, 4 °C) to pellet unbroken cells and nuclei. The low speed supernatants were subjected to ultracentrifugation (45,000 rpm (186,000 × g), 60 min, 4 °C). Membrane pellets were washed and resuspended in sonication buffer at 1–2 × 107 cell eq/ml, and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protocol with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Proteins were separated on 10% or 14% polyacrylamide gels using SDS-PAGE (50) and electrophoretically transferred overnight to nitrocellulose, and Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (51). Blots were blocked with 5% milk in TBST (10 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h, washed three times with TBST, and then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with appropriate primary antibody (anti-p47phox 1:1000 (gt) or 1:3000 (ms), anti-p67phox 1:1000, anti-gp91phox (54.1) 1:5000, or anti-p22phox (44.1) 1:1000). Blots were washed in TBST and then incubated in 5% milk/TBST for 1 h with appropriate species-specific horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:5000). Proteins were visualized using SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

In Vitro p22phox Phosphorylation

Membrane protein (40 μg) obtained from p22phox-transfected CHO 91/47/67 cells was mixed with solubilization buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and incubated on ice for 1 h. Samples were precleared with 5 μg of mouse IgG and 30 μl of 50% slurry of protein G-agarose (Sigma) for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were pelleted, and supernatants were removed and tumbled with 5 μg of monoclonal antibody 44.1 for 2 h. A 50% slurry of protein G-agarose (30 μl) was added and tumbled overnight at 4 °C. Agarose bound with p22phox was washed twice with solubilization buffer then once with PKC assay buffer (75 mm NaxPO4, pH 7.4, 7.5 mm MgCl2, 1.5 mm EGTA) before being resuspended in PKC assay buffer at a final volume of 69 μl. Five μl (100 ng) of PKC-α or PKC-δ and 6 μl (∼12 μCi) of [γ-32P]ATP were added to each tube just prior to the start of the reaction. PKC was activated by the addition of 30 μg/ml 10:0 1,2-didecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate, 10 μg/ml 1-oleoyl-2-acetoyl-sn-glycerol, and 0.6 mm CaCl2 (−CaCl2 for PKC-δ) for 30 min at 37 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. Beads were pelleted, and the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Phosphorylated p22phox was visualized by audioradiography. Western blot analysis with anti-p22phox antibody was then performed to confirm an equal p22phox protein amount/reaction.

p22phox-p47phox Interaction in Intact Cells

Transfected cells (1 × 107cells/ml) were incubated at 37 °C for stimulation with PMA or dimethyl sulfoxide. The membrane fraction, obtained from sonicated cells (sonication buffer: 10 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 25 mm NaF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm AEBSF) was solubilized and precleared with rabbit IgG and protein G-agarose beads as described above. An anti-p47phox antibody (rabbit, ∼1 μg of IgG/10 μg of membrane protein; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) plus protein G-agarose beads was used to immunoprecipitate (4 h, 4 °C) the p22phox·p47phox complex. Washed beads were prepared for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis by boiling in Laemmli sample buffer for 10 min. The immunoprecipitated proteins on blots were probed for both p22phox and p47phox content.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined based on p values from two-tailed Student's t tests using GraphPad Prism 4 (Hearne Scientific Software, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Characterization of the PMA Response in Transgenic CHO Cells

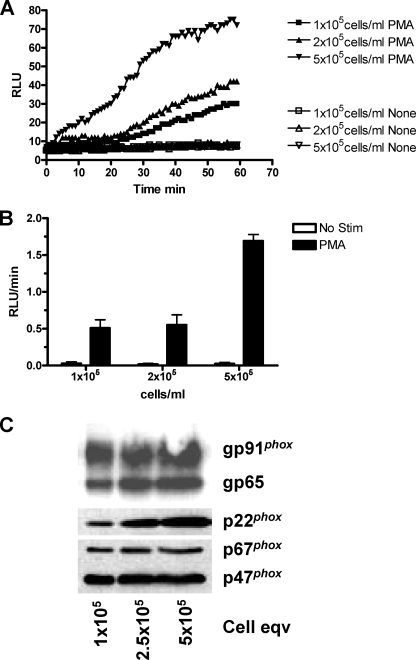

Previous reports (52) using CHO cells stably expressing NADPH oxidase components gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox (CHOphox) have shown that PMA stimulation results in superoxide production, but the response was not fully characterized. We confirmed that PMA stimulates NADPH oxidase activity in CHOphox cells (Fig. 1). CHOphox cells were incubated with or without 100 nm PMA in the presence of a luminol-based reagent (Diogenes) specific for the detection of superoxide. Light emission for each reaction was measured continuously over the indicated periods of time and plotted as a RLU versus time curve (Fig. 1A) or rate (RLU/min) as indicated under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 1B). PMA-dependent superoxide production increased as a function of cell concentration, and the characteristics of the response are similar to those published for human neutrophils (53). Western blot analysis of cell lysates (Fig. 1C) illustrates that all four of the NADPH oxidase components necessary for superoxide production were present. The gp65 protein is the precursor of gp91phox. These data indicate that CHOphox cells contain NADPH oxidase components and are stimulated by PMA to produce superoxide.

FIGURE 1.

CHOphox cells respond to PMA stimulation. CHO cells stably expressing the NADPH oxidase components gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox (CHOphox) were incubated at the indicated cell concentrations and stimulated with buffer or 100 nm PMA in the presence of 100 μl Diogenes. A, RLU were recorded over 60 min for unstimulated (None; open symbols) and stimulated (PMA; closed symbols) CHOphox cells at various concentrations. Data are from one experiment and are representative of three performed. B, summarized chemiluminescence rate data from three experiments (mean ± S.E. (error bars)) of RLU produced from 20 to 40 min are shown. C, whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Blots were probed for gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox and are representative of three separate experiments.

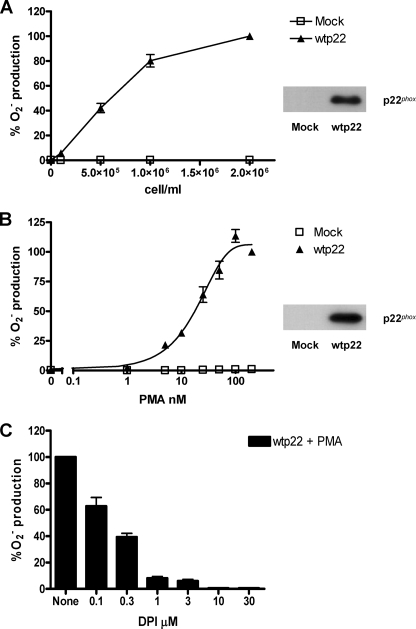

We next determined whether CHO cells stably expressing only gp91phox, p47phox, and p67phox (CHO 91/47/67) could produce superoxide in response to PMA when transiently transfected with p22phox. CHO 91/47/67 cells were transfected with mock or wild type p22phox DNA and evaluated for both for p22phox expression and PMA-stimulated respiratory burst activity using the chemiluminescence assay. In Fig. 2A, cells were stimulated with 100 nm PMA at varying cell concentrations. The cells expressing wild type p22phox (inset) demonstrated a cell concentration-dependent increase in superoxide production, which did not occur in mock transfected cells. Superoxide production was dependent on PMA concentration (Fig. 2B) and reached a maximum at ∼100 nm. Fig. 2C shows that diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a known NADPH oxidase inhibitor (54), inhibited PMA-stimulated superoxide production in a dose-dependent manner. Ten μm DPI completely inhibited the response. These data illustrate that CHO 91/47/67 cells transiently transfected to express wild type p22phox have the ability to produce superoxide as a result of PMA stimulation and that the superoxide produced is from reconstituted NADPH oxidase activity. Based on these results, the remainder of the experiments used 2 × 106 cells and 100 nm PMA.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of PMA-dependent superoxide production from CHO 91/47/67 cells transfected with wild type p22phox. A and B, CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing either no p22phox (Mock, □) or wild type p22phox (wtp22, ▲) were stimulated with 100 nm PMA at the indicated cell concentrations (A) or at 2 × 106 cells/ml with increasing PMA concentrations in the presence of 100 μl of Diogenes (B). The resulting activity was measured as RLU/min. Total p22phox protein was visualized by Western blot analysis (insets). C, CHO 91/47/67 cells at 2 × 106 cells/ml expressing wild type p22phox were incubated at 25 °C with the indicated concentrations of DPI for 5 min prior to stimulation with 100 nm PMA. Data were expressed as percent O2− production in the absence of DPI, and the mean ± S.E. (error bars) are shown. n = 3 for each graph.

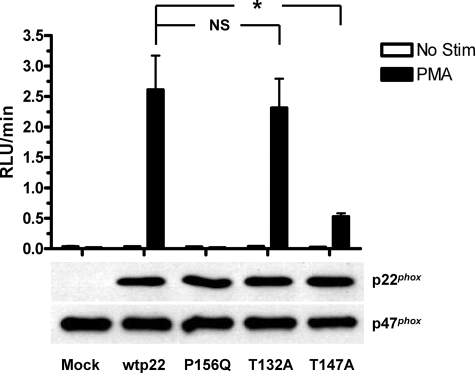

Mutation of Threonine 147 of p22phox to Alanine Inhibits NADPH Oxidase Activity

We utilized site-directed mutagenesis to explore the functional roles of potential phosphorylation sites in p22phox. We have shown previously that phosphorylation of p22phox in stimulated intact neutrophils occurs on one or more threonine residues (34). Analysis of the primary sequence of p22phox (NetPhos, NCBI) indicated that Thr-132 and Thr-147 were potential phosphorylation sites for protein kinases such as PKC, p38 MAPK, and casein kinase II. We generated threonine to alanine point mutants at these residues as well as a proline 156 to glutamine mutant. The latter inhibits NADPH oxidase activity by blocking p47phox binding to p22phox (55), and this construct was used as a positive control for inhibition of NADPH oxidase function by mutagenesis of p22phox. CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing no p22phox (mock), wild type (wtp22), or any of the three other point mutations in p22phox were stimulated with buffer (Fig. 3, open bars) or 100 nm PMA (filled bars) for measurement of oxidase activity in the chemiluminescence assay. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to monitor expression levels of both p22phox and p47phox. We observed a significant (p = 0.004) increase in stimulus-dependent NADPH oxidase activity from wild type p22phox-expressing cells compared with mock transfected cells. As expected, cells expressing the inactive p22phox mutant (P156Q) showed complete inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity compared with wild type, while still expressing equivalent levels of p22phox protein. In contrast, the PMA-stimulated response of cells expressing the p22phox T132A mutant was not significantly different from that of cells expressing wild type p22phox, suggesting that this threonine does not affect PMA-dependent NADPH oxidase activity. However, we saw a pronounced decrease of superoxide production from cells expressing the p22phox T147A mutant compared with that of wild type p22phox-expressing cells (p = 0.011). PMA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activity of the T147A mutant averaged less then 30% of the wild type response. The lower panels of Fig. 3 show the expression levels of the various p22phox constructs and of p47phox, which was used as a loading control. The wild type and T132A- and T147A-transfected cells showed similar levels of p22phox expression, and no detectable p22phox was present in mock transfected cells. Together, these results directly implicate the involvement of Thr-147 in the PMA-dependent stimulation of NADPH oxidase activity.

FIGURE 3.

PMA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activity by CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing p22phox point mutations. CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing either no p22phox (Mock), wild type p22phox (wtp22), Pro-156 to Gln p22phox (P156Q), Thr-132 to Ala p22phox (T132A), or Thr-147 to Ala p22phox (T147A) were stimulated at 2 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of 100 μl of Diogenes with either buffer (open bars) or 100 nm PMA (filled bars) for 1–2 h. Data represent four separate transfections and are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of the RLU/min measured from each p22phox condition. NS, not significant; *, p < 0.05. Western blot analysis for expression of p22phox and p47phox was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and the results from a representative experiment are shown.

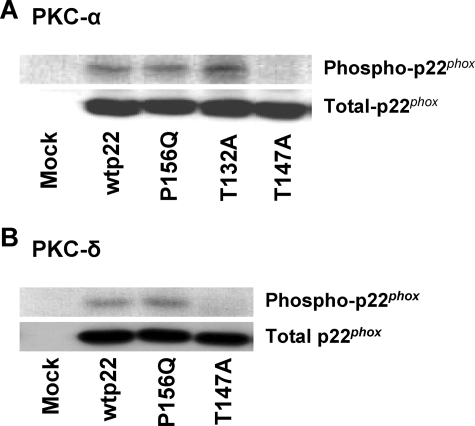

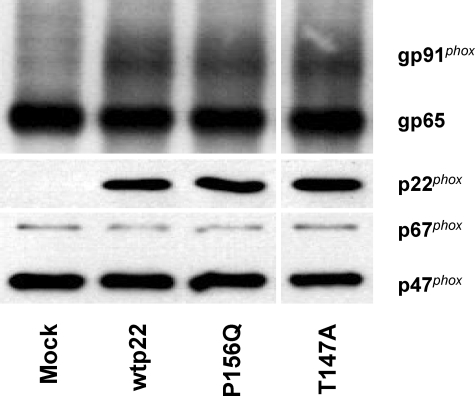

Threonine 147 of p22phox Is Phosphorylated by PKC-α and PKC-δ in Vitro

To address the hypothesis that threonine 147 is a phosphorylated residue of p22phox, we utilized an in vitro phosphorylation assay. We reported previously that p22phox in neutrophils could be phosphorylated in vitro by PKC isoforms (34). Immunoprecipitated p22phox from mock, wild type, and P156Q-, T132A-, and T147A-transfected CHO 91/47/67 cells was incubated in the presence of classical PKC-α (Fig. 4A) or novel PKC-δ (Fig. 4B). Both PKC isoforms phosphorylated wild type (wtp22), P156Q, and T132A p22phox. In contrast, we saw no phosphorylation of the T147A p22phox mutant (Fig. 4A). Total p22phox protein in the immunoprecipitates, detected by immunoblot analysis, showed similar protein levels for all of the mutants tested. These results implicate threonine 147 as the only phosphorylation site in p22phox.

FIGURE 4.

The p22phox mutant T147A is not phosphorylated by PKC-α or PKC-δ in vitro. Membrane protein from CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing no p22phox (Mock), wild type (wtp22), P156Q, T132A, or T147A p22phox was obtained as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p22phox was isolated by immunoprecipitation with monoclonal antibody 44.1 and phosphorylated by 100 ng of either PKC-α (A) or -δ (B). Reactions were stopped by the addition of Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose, and radiolabeled p22phox was visualized by autoradiography. Blots were then subjected to Western blot analysis and probed for total p22phox. Blots are representative of at least two separate transfections.

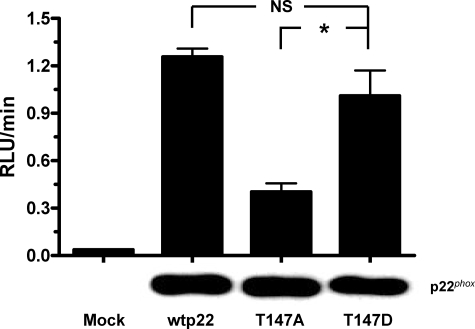

Mimicking Phosphorylation of Threonine 147 in Vivo Restores NADPH Oxidase Activity

To address whether phosphorylation of threonine 147 in p22phox regulates PMA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activation in intact cells, we mutated Thr-147 to an aspartate (T147D). This mutation mimics the negative charge that results from the addition of a phosphate group through phosphorylation. When we stimulated CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing the T147D p22phox mutation with 100 nm PMA in the presence of Diogenes, superoxide production returned to a level comparable with that elicited by wild type cells (Fig. 5). Activity in cells expressing the T147D mutant was significantly higher than that in the T147A mutant-expressing cells (p = 0.028), but not from that of cells expressing wild type p22phox. Western blot analysis showed that all constructs were expressed at equal levels. These results suggest that phosphorylation of p22phox during PMA stimulation occurs on threonine 147 and that this phosphorylation enhances NADPH oxidase activity.

FIGURE 5.

Mimicking phosphorylation of threonine 147 in vivo restores NADPH oxidase activity. CHO 91/47/67 expressing no p22phox (Mock), wild type (wtp22), T147A, or T147D p22phox were resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml and stimulated for 2 h with 100 nm PMA in the presence of 100 μl of Diogenes. Activity was measured according “Experimental Procedures.” Data represent three separate transfections and are shown as the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of the RLU/min. *, p < 0.05. NS, not significant. Western blot analysis probing for total p22phox expression is shown below the bars for one of the three experiments.

Effects of T147A on the Functional Roles of p22phox

We explored the mechanism by which the phosphorylation of p22phox regulates NADPH oxidase activity. One of the known functions of p22phox is to promote the maturation of gp91phox from its gp65 precursor (46). To determine whether the p22phox mutants affect gp91phox maturation, we prepared whole cell lysates from CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing no p22phox (mock), wild type (wtp22), P156Q, or T147A p22phox and subjected them to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Blots were probed for p22phox and for mature and immature gp91phox. Fig. 6 shows that when p22phox is not expressed in these cells (Mock), only the immature gp65 component was observed. In contrast, the cells expressing wild type, P156Q, and T147A p22phox show the characteristic broad band of mature, glycosylated gp91phox in similar amounts. p22phox expression did not differ among the wtp22-, P156Q-, and T147A-expressing cells, and equal sample loading was confirmed by assessing p47phox and p67phox expression. These results indicate that maturation of gp91phox is not affected by the T147A mutation. Thus, an alteration in gp91phox maturation cannot explain the mechanism by which Thr-147 regulates NADPH oxidase activity.

FIGURE 6.

Maturation of gp91phox is not affected by the T147A p22phox mutant. Whole cell lysates of CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing none (Mock), wild type (wtp22), P156Q, and T147A p22phox were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis according to “Experimental Procedures.” Blots are representative of at least three separate transfections.

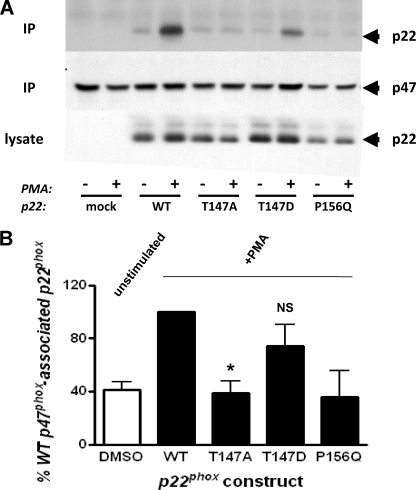

Another known function of p22phox within the active NADPH oxidase complex is that of anchoring p47phox through the proline rich region (PRR)-Src homology 3 (SH3) domain protein-protein interaction (56). This interaction helps to tether the cytosolic p47phox component in the membrane after translocation. As a measure of this translocation event, we assessed the interaction of p47phox with p22phox in the membrane fraction prepared from stimulated and unstimulated cells. CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing no p22phox (mock), wild type, P156Q, T147A, or T147D p22phox were incubated at 37 °C in the absence or presence of 100 nm PMA for 10 min. p47phox was immunoprecipitated from the solubilized membrane fraction to evaluate the amount of p22phox co-immunoprecipitating with the translocated protein. Fig. 7A shows that p22phox co-immunoprecipitated with p47phox in a PMA-dependent manner in cells expressing either the wild type or T147D p22phox (Fig. 7, top panel). The T147D mutant promoted ∼75% of the p22phox-p47phox interaction as that of wild type p22phox (Fig. 7B). In contrast, T147A p22phox failed to interact with p47phox in a stimulus-dependent fashion. Likewise, the P156Q mutation blocked the p22phox-p47phox interaction, as expected. Neither of these mutations (T147A or P156Q) promoted a p22phox-p47phox interaction in the membrane fraction of PMA-stimulated cells to an extent greater than that observed in unstimulated cells (Fig. 7B). The p47phox content of the immunoprecipitates (middle panel) and the p22phox expression levels in the cell lysates (bottom panel) were comparable among transfected cells and stimulation conditions. These data suggest that the negatively charged state of p22phox Thr-147, either due to phosphorylation or mutation to aspartate, facilitates the interaction of p47phox with p22phox in the stimulated cells. Importantly, the charge on Thr-147 does not appear to influence the basal interaction of the two oxidase components in the unstimulated cell.

FIGURE 7.

The p47phox-p22phox interaction in the membrane of CHO 91/47/67 cells is dependent on the phosphorylation status of Thr-147. CHO 91/47/67 cells expressing no p22phox (mock), wild type (WT), T147A, T147D, or P156Q p22phox were stimulated with dimethyl sulfoxide (−) or 100 nm PMA (+) for 10 min, disrupted by sonication, fractionated, and the membrane fraction was solubilized as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p47phox was immunoprecipitated (IP) from solubilized membrane; the immunoprecipitated proteins and those in a whole cell lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for p47phox and p22phox content. A, blots of p22phox (top panel) and p47phox (middle panel) in immunoprecipitates and p22phox in whole cell lysates (bottom panel) from a representative experiment are shown. B, p47phox-associated p22phox in immunoprecipitates was normalized to p47phox content and expressed as percent of that in PMA-stimulated wild type p22phox-expressing cells. The open bar represents the mean of unstimulated conditions for all p22phox constructs. The filled bars are the PMA-stimulated conditions for the indicated p22phox construct. The data are the mean ± S.E. (error bars; n = 3). The p47phox-associated p22phox is significantly different from the wild type condition where indicated (*, p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation is a key regulatory step in the activation of NADPH oxidase (24). The predominant protein kinase-oxidase component interactions that have been studied within the process of NADPH oxidase enzyme complex formation involve the cytosolic subunits p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox. These proteins are known to be phosphorylated by PKC isoforms, PAK, p38 MAPK, cAMP-dependent, and possibly 1,2-didecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate-activated protein kinases (24). Phosphorylation of flavocytochrome b558 has been poorly studied but was first described in 1988 (57). We subsequently demonstrated that PKC isoforms could phosphorylate p22phox on threonine residue(s) (34) and that this phosphorylation event correlated with NADPH oxidase activation (58). Here, we identify the site of the phosphorylation. Moreover, we show that phosphorylation of p22phox enhances NADPH oxidase activity and regulates the p22phox-p47phox interaction in the membrane.

Most cells express p22phox mRNA (40, 41), making the exploration of the functional role of phosphorylation difficult in the presence of wild type protein. We first attempted to examine the function of p22phox mutants in K562phox cells (59), but effects on superoxide production were minimal.4 In contrast, transgenic CHO cells stably expressing gp91phox, p67phox, and p47phox were completely dependent on expression of wild type p22phox for NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 2). We first characterized the PMA-stimulated superoxide production in these cells (Fig. 1) because previous work had reported only low levels of superoxide production in response to this stimulus (46, 52). PMA-stimulated superoxide production was easily measured using a Diogenes-based chemiluminescence method and was completely inhibitable by DPI, indicating that superoxide production was a direct result of p22-dependent NADPH oxidase activity. Thus, the transgenic CHO cell system appears to be a faithful model of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase with the added advantage of being able to manipulate the expression of the component proteins.

We used the CHO cell system to identify a functional phosphorylation site in p22phox. Both threonine 132 and 147 have been recognized as putative phosphorylation motifs (58). Our results clearly identified threonine 147 as the only site phosphorylated by PKC in p22phox. The ability of endogenous protein kinases to phosphorylate this residue markedly enhanced NADPH oxidase activation by PMA (Fig. 3). However, the PMA-dependent NADPH oxidase activity was not completely blocked by T147A, suggesting that other regulatory events such as protein-protein interactions and lipid involvement can result in some superoxide production. Interestingly, converting Thr-147 to Asp, which mimics the charge conferred by phosphorylation, restored the ability of PMA to stimulate full activation of the oxidase. This provides further evidence that the role of Thr-147 in wild type p22phox is to undergo phosphorylation. PMA stimulation was still necessary to observe NADPH oxidase activity with the T147D mutant, presumably due to the requirement for phosphorylation of other NADPH oxidase components, such as p47phox, to induce activation (24).

Our results also showed that Thr-147 is a substrate for representatives of the classical and novel isoforms of PKC in vitro (Fig. 4). Previously, we did not observe phosphorylation of p22phox by PKC-δ (34). This can be attributed to our use of different conditions for the phosphorylation reaction in the current experiments, including the substitution of phosphatidic acid for phosphatidylserine to activate PKC.5 Although these observations suggest that PKC directly phosphorylates Thr-147 in response to PMA during NADPH oxidase activation, we cannot rule out the involvement of other protein kinases in the phosphorylation of p22phox.

The known functions for p22phox in NADPH oxidase activation are the promotion of heterodimer formation with gp91phox during neutrophil maturation and anchoring p47phox in the membrane upon cell stimulation (15). In agreement with previous work in which residues 142–195 were deleted (46), we observed that the T147A mutation had no effect on gp91phox maturation (Fig. 6).

The assembly of the NADPH oxidase components in the membrane is essential for the activation of the functional enzyme. Both p22phox and p47phox are central to the assembly process as evidenced by the identified P156Q mutation in p22phox, which is known to abolish the p22phox-p47phox interaction (55). Indeed, we observed that the expression of P156Q p22phox in CHO 91/47/67 cells failed to permit PMA-stimulated superoxide production (Fig. 3) and interaction with p47phox (Fig. 7). We now show clear evidence that the phosphorylation state of p22phox can also regulate the stimulus-dependent interaction between p22phox and p47phox in the intact cell. The T147A mutant of p22phox could not be phosphorylated in vitro by PKC isoforms (Fig. 4), greatly diminished PMA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 3), and failed to allow for the PMA-stimulated interaction with endogenous p47phox in intact cells (Fig. 7). Importantly, the expression of the T147D mutant of p22phox, which mimics the charge of phosphorylation, restored the ability of p47phox to interact with p22phox and NADPH oxidase activity in stimulated cells. These observations suggest that both the PRR-SH3 interaction (requiring proline 156) and the p47phox-phospho-p22phox interaction (mediated by threonine 147) are essential for the optimal assembly of the functional NADPH oxidase complex in intact cells. We speculate that because of the close proximity of Thr-147 to the PRR domain of p22phox, phosphorylation of Thr-147 may allow for more efficient binding of p47phox to the flavocytochrome via the PRR-SH3 interaction (60). It is also possible that phosphorylation of Thr-147 alters the positioning of the entire cytosolic complex, resulting in a more favorable conformation for electron flow through gp91phox. Finally, changes in conformation of p22phox resulting from phosphorylation of Thr-147 may alter the conformation of gp91phox through their heterodimer interactions. This change could allow for more efficient binding between gp91phox and cytosolic components or allow for more efficient transfer of electrons from NADPH to FAD, FAD to heme, and/or heme to molecular oxygen.

It is noteworthy that the T147D mutation of p22phox, which mimics the negative charge of the phosphorylated state at that residue, did not alter the interaction of p22phox and p47phox in unstimulated cells (Fig. 7A) even though it restored the PMA-stimulated interaction. This suggests that stimulation-induced changes occur in the cytosolic oxidase complex which allow for their interaction with the membrane oxidase components. The phosphorylation of p47phox is one such event. We observed no effect of the p22phox mutations on the phosphorylation of p47phox when detected by a phospho-specific antibody directed toward the phosphorylation motif of PKC substrates (data not shown). It is possible that the constellation of sites phosphorylated in p47phox could be influenced by p22phox, but such studies require more sensitive approaches, such as the use of site-specific phospho-antibodies for p47phox, which are not currently available.

Although homologues for gp91phox, p47phox, and p67phox have been discovered in numerous cells throughout the body, a homologue for p22phox has not been seen (61). Instead, studies have found that p22phox is essential for superoxide production by three of the four gp91phox homologues (44, 62). Because of this, it will be interesting to determine (i) whether phosphorylation of p22phox on Thr-147 occurs while complexed with these homologues and (ii) whether the phosphorylation of p22phox affects NADPH oxidase function of these homologues. Studies addressing these questions are ongoing in our laboratory.

In conclusion, the reconstituted CHO cell system can be used to study point mutations in p22phox through PMA-dependent NADPH oxidase activity. Exploiting this system, we determined that threonine 147 of p22phox is phosphorylated in a PMA-dependent manner and that this modification is required for optimal NADPH oxidase activity. Using an in vitro phosphorylation assay, we observed that both PKC-α and PKC-δ phosphorylate Thr-147. Although gp91phox maturation was not affected by the p22phox point mutations employed, we observed that the T147A mutation reduced both the PMA-stimulated interaction of p22phox with p47phox and NADPH oxidase activity. Because NADPH oxidase activity has now been implicated in a growing number of disease states and its components are being discovered in a wide variety of cell types, it is important to understand the exquisite regulation of this enzyme.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI 22564 (to L. C. M.) and R01 HL 045635 (to M. C. D.). This work was also supported by March of Dimes Research Foundation Grant MOD 1-FY02-191 (to L. C. M.).

E. M. Lewis, S. Sergeant, and L. C. McPhail, unpublished results.

F. Lu and L. C. McPhail, unpublished results.

- p47phox

- 47-kDa protein of phagocytic oxidase

- p67phox

- 67-kDa protein of phagocytic oxidase

- p40phox

- 40-kDa protein of phagocytic oxidase

- p22phox

- 22-kDa protein of phagocytic oxidase

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- RLU

- relative light units

- DPI

- diphenyleneiodonium

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PRR

- proline-rich region

- SH3

- Src homology 3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiernik P. H. (1985) Mediguide Oncol. 1, 1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPhail L. C., Harvath L. (1993) in The Neutrophil ( Abramson J. S., Wheeler J. G. eds) pp. 63–107, Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi S. D., Voyich J. M., Burlak C., DeLeo F. R. (2005) Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 53, 505–517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greaves D. R., Schall T. J. (2000) Microbes Infect. 2, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schall T. J., Bacon K. B. (1994) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6, 865–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jesaitis A. J., Quinn M. T., Mukherjee G., Ward P. A., Dratz E. A. (1991) New Biol. 3, 651–655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch R. E. (1983) Top. Curr. Chem. 108, 35–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roos D., van Bruggen R., Meischl C. (2003) Microbes Infect. 5, 1307–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambeth J. D. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Light D. R., Walsh C., O'Callaghan A. M., Goetzl E. J., Tauber A. I. (1981) Biochemistry 20, 1468–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis J. A., Cross A. R., Jones O. T. (1989) Biochem. J. 262, 575–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotrosen D., Yeung C. L., Leto T. L., Malech H. L., Kwong C. H. (1992) Science 256, 1459–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vignais P. V. (2002) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1428–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biberstine-Kinkade K. J., DeLeo F. R., Epstein R. I., LeRoy B. A., Nauseef W. M., Dinauer M. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31105–31112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauseef W. M. (2004) Histochem. Cell Biol. 122, 277–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rask-Madsen C., King G. L. (2007) Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 3, 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu W. S. (2006) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25, 695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Infanger D. W., Sharma R. V., Davisson R. L. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1583–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cave A. C., Brewer A. C., Narayanapanicker A., Ray R., Grieve D. J., Walker S., Shah A. M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 691–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn M. T., Ammons M. C., Deleo F. R. (2006) Clin. Sci. 111, 1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leto T. L., Geiszt M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1549–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyworth P. G., Cross A. R., Curnutte J. T. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 578–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeya R., Sumimoto H. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1523–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheppard F. R., Kelher M. R., Moore E. E., McLaughlin N. J., Banerjee A., Silliman C. C. (2005) J. Leukocyte Biol. 78, 1025–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groemping Y., Rittinger K. (2005) Biochem. J. 386, 401–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Decoursey T. E., Ligeti E. (2005) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2173–2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPhail L. C., Qualliotine-Mann D., Agwu D. E., McCall C. E. (1993) Eur. J. Haematol. 51, 294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perisic O., Wilson M. I., Karathanassis D., Bravo J., Pacold M. E., Ellson C. D., Hawkins P. T., Stephens L., Williams R. L. (2004) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 44, 279–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu D. J., Furuya W., Grinstein S. (1993) Blood Cells 19, 343–351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waki K., Inanami O., Yamamori T., Nagahata H., Kuwabara M. (2006) Free Radic. Res. 40, 359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox J. A., Jeng A. Y., Sharkey N. A., Blumberg P. M., Tauber A. I. (1985) J. Clin. Invest. 76, 1932–1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCall C. E., McPhail L. C., Salzer W. L., Schmitt J. D., Nasrallah V., Kim J., Wykle R. L., O'Flaherty J. T., Bass D. A. (1985) Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 98, 253–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dang P. M., Fontayne A., Hakim J., El Benna J., Périanin A. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 1206–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regier D. S., Waite K. A., Wallin R., McPhail L. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36601–36608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reeves E. P., Dekker L. V., Forbes L. V., Wientjes F. B., Grogan A., Pappin D. J., Segal A. W. (1999) Biochem. J. 344, 859–866 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeChatelet L. R., Shirley P. S., Johnston R. B., Jr. (1976) Blood 47, 545–554 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selvatici R., Falzarano S., Mollica A., Spisani S. (2006) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 534, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontremoli S., Melloni E., Sparatore B., Salamino F., Michetti M., Sacco O. (1986) Ital. J. Biochem. 35, 368–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuzawa S., Suzuki N. N., Fujioka Y., Ogura K., Sumimoto H., Inagaki F. (2004) Genes Cells 9, 443–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng G., Cao Z., Xu X., van Meir E. G., Lambeth J. D. (2001) Gene 269, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkos C. A., Dinauer M. C., Walker L. E., Allen R. A., Jesaitis A. J., Orkin S. H. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3319–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawahara T., Ritsick D., Cheng G., Lambeth J. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31859–31869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price M. O., McPhail L. C., Lambeth J. D., Han C. H., Knaus U. G., Dinauer M. C. (2002) Blood 99, 2653–2661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ueno N., Takeya R., Miyano K., Kikuchi H., Sumimoto H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23328–23339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeya R., Ueno N., Kami K., Taura M., Kohjima M., Izaki T., Nunoi H., Sumimoto H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25234–25246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu Y., Marchal C. C., Casbon A. J., Stull N., von Löhneysen K., Knaus U. G., Jesaitis A. J., McCormick S., Nauseef W. M., Dinauer M. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30336–30346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burritt J. B., Quinn M. T., Jutila M. A., Bond C. W., Jesaitis A. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16974–16980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leto T. L., Garrett M. C., Fujii H., Nunoi H. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19812–19818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caldwell S. E., McCall C. E., Hendricks C. L., Leone P. A., Bass D. A., McPhail L. C. (1988) J. Clin. Invest. 81, 1485–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 4350–4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biberstine-Kinkade K. J., Yu L., Stull N., LeRoy B., Bennett S., Cross A., Dinauer M. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30368–30374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tauber A. I., Brettler D. B., Kennington E. A., Blumberg P. M. (1982) Blood 60, 333–339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cross A. R., Jones O. T. (1986) Biochem. J. 237, 111–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leusen J. H., Bolscher B. G., Hilarius P. M., Weening R. S., Kaulfersch W., Seger R. A., Roos D., Verhoeven A. J. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 2329–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nobuhisa I., Takeya R., Ogura K., Ueno N., Kohda D., Inagaki F., Sumimoto H. (2006) Biochem. J. 396, 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia R. C., Segal A. W. (1988) Biochem. J. 252, 901–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regier D. S., Greene D. G., Sergeant S., Jesaitis A. J., McPhail L. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28406–28412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Mendez I., Leto T. L. (1995) Blood 85, 1104–1110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sumimoto H., Hata K., Mizuki K., Ito T., Kage Y., Sakaki Y., Fukumaki Y., Nakamura M., Takeshige K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22152–22158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bedard K., Krause K. H. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 245–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ambasta R. K., Kumar P., Griendling K. K., Schmidt H. H., Busse R., Brandes R. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45935–45941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]