Abstract

During the initial autoimmune response in type 1 diabetes, islets are exposed to a damaging mix of pro-inflammatory molecules that stimulate the production of nitric oxide by β-cells. Nitric oxide causes extensive but reversible cellular damage. In response to nitric oxide, the cell activates pathways for functional recovery and adaptation as well as pathways that direct β-cell death. The molecular events that dictate cellular fate following nitric oxide-induced damage are currently unknown. In this study, we provide evidence that AMPK plays a primary role controlling the response of β-cells to nitric oxide-induced damage. AMPK is transiently activated by nitric oxide in insulinoma cells and rat islets following IL-1 treatment or by the exogenous addition of nitric oxide. Active AMPK promotes the functional recovery of β-cell oxidative metabolism and abrogates the induction of pathways that mediate cell death such as caspase-3 activation following exposure to nitric oxide. Overall, these data show that nitric oxide activates AMPK and that active AMPK suppresses apoptotic signaling allowing the β-cell to recover from nitric oxide-mediated cellular stress.

Keywords: Cell/Apoptosis, Cytokines/Interleukins, Diseases/Diabetes, Enzymes/Kinase, Hormones/Insulin, Radicals, Signal Transduction, Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases, AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK), Nitric Oxide

Introduction

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation in and around pancreatic islets followed by the selective destruction of insulin-secreting β-cells (1, 2). The mechanisms leading to β-cell death likely involve pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)3-1, TNFα, and INFγ produced by the resident islet macrophages and the invading leukocytes (3, 4).

Exposure of rat islets to IL-1 results in inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, metabolic dysfunction, and cell death (5, 6). Many of the damaging actions of IL-1 on β-cells are dependent on the expression of the inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) and the subsequent generation of micromolar levels of the free radical nitric oxide (7). High concentrations of nitric oxide damages cells through multiple mechanisms including post-translational modifications (S-nitrosylation, tyrosine nitration) of enzymes, destruction of iron-sulfur complexes in enzymes, such as aconitase, resulting in the inhibition of oxidative metabolism, and the induction of DNA damage (6, 8, 9, 10, 11).

Even though IL-1 induces extensive nitric oxide-dependent damage, β-cells maintain a temporally limited ability to repair the damage and regain function upon inhibition of nitric oxide production. Removal of IL-1 following a 15-h incubation and continued culture for 4 days in the absence of IL-1 results in a restoration of insulin secretion by islets (12). This recovery period can be dramatically shortened from 4 days to 8 h by blocking nitric oxide production using inhibitors of iNOS (13). The mechanisms regulating recovery from cytokine and nitric oxide-induced damage are largely unknown. We have shown that nitric oxide not only causes cellular damage but also initiates the recovery process through a mechanism that requires JNK activation and new gene expression (14, 13). Identifying proteins that regulate this recovery process represents a pool of novel targets that may have potential therapeutic value in strategies designed to attenuate the loss of β-cell mass; for example in the transplantation setting.

Recently, inflammatory cytokines were reported to activate the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in pancreatic islets (15). AMPK is a heterotrimeric (α, β, and γ subunits) serine/threonine kinase critical to the maintenance of cellular energy homeostasis. The α-subunit (AMPKα) possesses the kinase activity; the β-subunit functions as a scaffold molecule; and the γ-subunit senses the cellular energy status by binding to AMP and ATP. When the AMP/ATP ratio increases AMP binds the γ-subunit leading to activation of AMPK by inducing a conformational change that blocks dephosphorylation of threonine 172. Once active, AMPK phosphorylates many downstream effectors to reduce ATP consuming processes and promote ATP-producing processes (16). The constitutively active kinase LKB1 phosphorylates AMPK at threonine 172, and together with increased AMP, activates AMPK (17, 18). LKB1 is thought to be the predominant kinase responsible for the activating phosphorylation of AMPK; however, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β (CaMKKβ) can function as an alternative kinase to activate AMPK independent of cellular energy content (19).

Currently, the role of AMPK in the functional recovery of β-cells from nitric oxide-induced damage is unknown. In this report, we provide experimental evidence that cytokines activate AMPK in a nitric oxide-dependent fashion and that AMPK functions to attenuate death and promote the functional recovery of β-cells from nitric oxide-mediated stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). INS832/13 cells were obtained from Chris Newgard (Duke University, Durham NC). RPMI 1640, CMRL-1066 tissue culture medium, l-glutamine, streptomycin, and penicillin were from Mediatech, Inc. (Manassas, VA). Fetal calf serum was from Sigma. Human recombinant IL-1 was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMMA) and (Z)-1(N,N-diethylamino) diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (DEA-NO) were purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA). Camptothecin was from Sigma. Phospho-Thr172-AMPK, phospho-Ser79-ACC, phospho-Ser473-Akt, phospho-Ser51-eIF2α, total AMPK, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), Bcl2, BclXL (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), HSP90, HSP70, (Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada), CHOP/GADD153 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), GAPDH (Ambion,) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and donkey anti-mouse were from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc (West Grove, PA). PGC1α, CHOP, GADD45α, and GAPDH primers were from IDT DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and were lysed with IP lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 100 μm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 50 mm sodium fluoride, and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 20,800 × g for 15 min. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay. Samples were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (2% SDS) and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 min. Proteins were resolved in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and the membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse, donkey anti-rabbit, or donkey anti-rat IgG (1:7000 dilution), followed by detection with enhanced chemiluminescence.

Islet Isolation

Islets were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) by collagenase digestion as previously described (20). Islets were cultured overnight in complete CMRL-1066 (containing 2 mmol/liter l-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 before experimentation.

Cell Culture

INS832/13 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 55 μm β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mm HEPES, and 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Nitrite Determination

Nitrite levels were determined using a 1:1 mix of culture supernatant and Greiss reagent (21). Absorbance was measured at 540 nm, and concentrations were determined from a sodium nitrite standard curve.

Aconitase Assay

INS832/13 cells were isolated by centrifugation, and mitochondrial aconitase activity was determined as described previously (14). Briefly, aconitase was assayed at 340 nm in a reaction containing 20 mm citrate, 0.2 mm nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, 6 mm MnCl2, 50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 0.6 units of isocitrate dehydrogenase, and 50 μl of cell extract in a total volume of 200 μl using a microtiter plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) at room temperature. Aconitase activity was quantified as 1 pmol of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) formed per minute per microgram of protein.

TUNEL Assay

Following treatment, cells were collected in PBS and centrifuged onto slides using a cytospin. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% citrate for 3 min. The samples were labeled following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Manheim, Germany). DNA damage was quantified by counting TUNEL-positive cells. In each experiment, a minimum of 300 cells per condition were counted.

Comet Assay

DNA damage was assessed using the comet assay (single cell gel electrophoresis) as described previously (22, 23). Briefly, cells were harvested and embedded in 0.6% low melting agarose on slides precoated with 1.0% agar. Samples were then incubated in lysing solution (2.5 m NaCl, 100 mm EDTA, 10 mm Trizma base, 1% Triton X-100) overnight. Following lysis, the slides were incubated in an alkaline electrophoresis buffer (0.3 m NaOH, 1 mm EDTA, pH > 13) for 40 min followed by electrophoresis at 25 V/300 mA for 20 min. Slides were washed three times in 0.4 m Tris, pH 7.5, and stained with ethidium bromide (2 μg/ml). Comet images were captured using a Nikon eclipse 90i, and the CASP program was used to quantify the mean tail moment from 30–50 cells per condition.

Caspase-3 Assay

The caspase-3 assay was modified from Ref. 24. Following treatments, 200 μl of 3× caspase buffer (150 mm HEPES, 450 mm NaCl, 150 mm KCl, 30 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm EGTA, 1.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.3% CHAPS, 30% sucrose, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 μm DEVD-AMC) was added to the cells (2 × 105) in a 24-well plate with 400 μl of medium and incubated for 30 min at 37°c. Release of the fluorochrome was measured by fluorescence (BioTek Instruments inc., Winooski, VT) using an excitation of 360 nm and emission of 460 nm.

Adenoviral Transduction

Adenoviruses carrying WT-AMPKα, DN-AMPKα2 (K45R), or CA-AMPKγ1 (H150R) transgenes were generated as previously described (25). Cells were plated and transduced simultaneously. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight (∼16 h) then were washed with medium and cultured an additional 24 h before experimentation.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Karmer post-hoc test or, for paired samples, repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

RESULTS

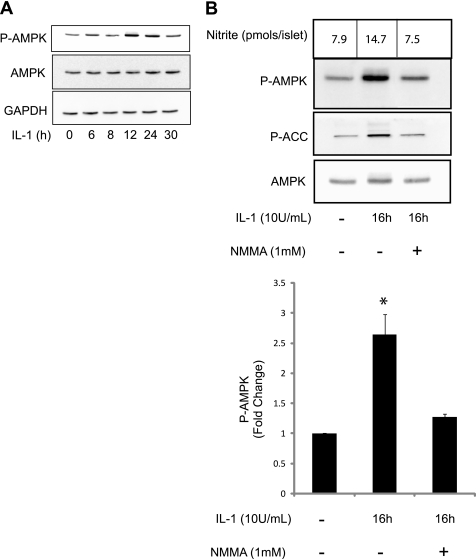

IL-1 Induces Nitric Oxide-dependent Activation of AMPK

AMPK is a stress-activated kinase that is regulated by the energy status of the cell. Because IL-1 treatment in islets attenuates oxidative metabolism and reduces ATP levels (9) the effects of this cytokine on AMPK phosphorylation was examined using antibodies for the activation-associated phospho-Thr172-AMPK (26). IL-1 induces a transient phosphorylation of AMPK following 12 and 24 h incubations. AMPK phosphorylation returns to basal levels following 30 h of incubation with IL-1 (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the previous experiment, treatment with IL-1 for 16 h significantly increased the phosphorylation of AMPK and the AMPK substrate ACC indicating that AMPK phosphorylation on Thr-172 is consistent with kinase activation. IL-1-induced AMPK and ACC phosphorylation is attenuated by the nitric-oxide synthase inhibitor NMMA (Fig. 1B), and aminoguanidine a second inhibitor selective for the inducible isoform of NOS (not shown) indicating that the actions of this cytokine are mediated by nitric oxide. These findings show that IL-1 stimulates AMPK activation in islets in a nitric oxide-dependent fashion.

FIGURE 1.

IL-1 induces nitric oxide-dependent activation of AMPK. Rat islets (150 islets/400 μl medium) were treated with 10 units/ml IL-1 for 0–30 h. Phosphorylated and total AMPK was measured by Western blot analysis using GAPDH as a protein loading control (A). Rat islets were treated with 10 units/ml IL-1 without or with 1 mm NMMA for 16 h. Phosphorylated AMPK and ACC and total AMPK were measured by Western blot analysis and quantified by densitometry (B). Results are representative of two independent experiments (A) or means ± S.E. of three independent experiments with statistical significant differences; *, p < 0.05 (B).

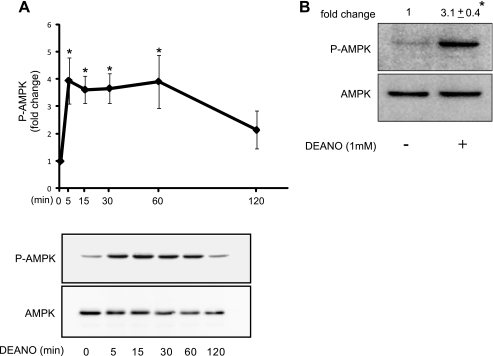

The Nitric Oxide Donor DEANO Activates AMPK in INS832/13 Cells and Islets

Exogenously provided nitric oxide using the donor diethylamine NONOate (DEANO) stimulates rapid and transient AMPK phosphorylation in INS832/13 cells (Fig. 2A). Similarly, treatment of intact rat islets with 1 mm DEANO for 30min induces a significant 3.1 ± 0.4-fold (p < 0.05) increase in the phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 2B). Inactivated DEANO fails to stimulate AMPK phosphorylation indicating that the action of this donor is due to the release of nitric oxide (data not shown). These data confirm that nitric oxide is sufficient to stimulate AMPK phosphorylation.

FIGURE 2.

DEANO activates AMPK in INS832/13 and islets. INS832/13 cells were treated with 1 mm DEANO for the indicated times. The levels of phosphorylated and total AMPK were determined by Western blot analysis and quantified by densitometry (A). Rat islets (150 islets/400 μl medium) were treated with 1 mm DEANO for 30 min followed by examination of phosphorylated and total AMPK by Western blot analysis and quantified by densitometry (B). Results are means ± S.E. of three independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05.

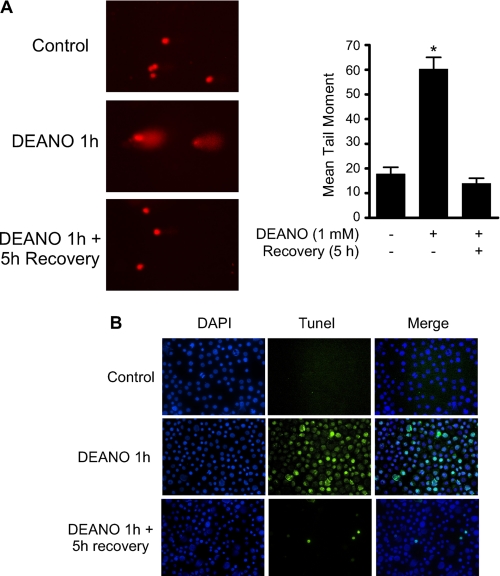

Nitric Oxide Causes Extensive DNA Damage but Induces Mild Caspase-3 Activation

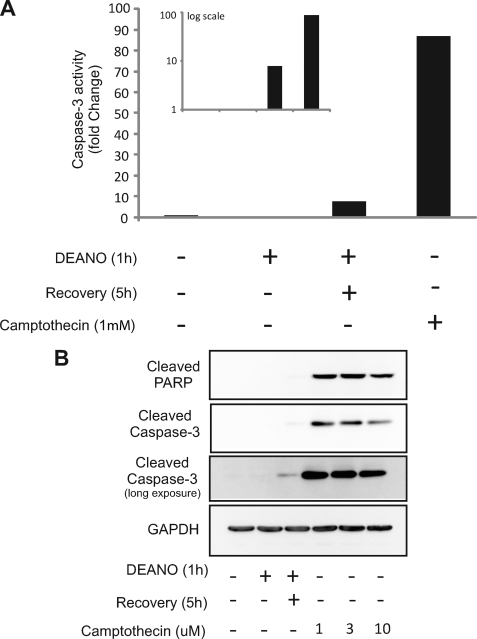

We have previously reported that the damaging actions of IL-1 and nitric oxide on metabolic function and DNA integrity are reversible (27, 28). Consistent with these previous findings, treatment of INS832/13 cells with DEANO for 1 h induced DNA damage as measured at the single cell level by the Comet assay (Fig. 3A) or TUNEL (Fig. 3B). Removal of nitric oxide by washing followed by incubation for an additional 5 h in the absence of DEANO results in the repair the damaged DNA (Fig. 3A and Ref. 28). Interestingly, not all cells repair damaged DNA. A limited number of cells (∼4.5%) acquire an apoptotic morphology that includes punctate nuclei and DNA damage as shown by TUNEL staining (Figs. 3B and 9). Under these recovery conditions, there is an accumulation of mRNA of proapoptotic genes including CHOP and PUMA as well as mRNA accumulation of genes promoting DNA repair, GADD45, and mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC1α (Fig. 4A). Despite DNA damage and proapoptotic gene expression, there is a surprisingly low level of caspase-3 activation. There is an 8-fold increase in caspase activity in INS832/13 cells treated with DEANO for 1 h followed by washing to remove the nitric oxide and an additional 5-h incubation (Fig. 5A, inset). To more fully understand the level of apoptosis, the effects of nitric oxide were compared with known inducers of apoptosis such as the topoisomerase inhibitor camptothecin. Whereas nitric oxide seems to increase caspase cleavage and activity, the level of caspase activation is very low. As shown in Fig. 5, camptothecin stimulates ∼90-fold increase in caspase-3 activity. This level of caspase activity is over 10-fold higher than the levels induced by DEANO (Fig. 5A, inset shows log scale).This low level of caspase activity correlates with a very slight increase in cleaved caspase-3 (detectable only following prolonged exposures) and the absence of detectable PARP cleavage (a substrate of caspase-3; Fig. 5B). Unlike the small increase in caspase-3 activity in response to DEANO, camptothecin-induced caspase-3 enzymatic activity correlates with caspase-3 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 5B). These findings suggests that mechanisms may be in place to prevent nitric oxide-induced β-cell apoptosis as nitric oxide stimulates high levels of DNA damage yet caspase-3 activation is minimal (when compared with known apoptosis inducers) even in the presence of extensive damage. These protective mechanisms may facilitate the repair of cellular damage and metabolic recovery from nitric oxide-mediated damage.

FIGURE 3.

Nitric oxide causes reversible DNA damage. INS832/13 cells were treated with 1 mm DEANO or 1 h with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and a 5-h incubation in the RPMI 1640. DNA damage was determined using the Comet assay (A) or TUNEL staining (B). Results are the average ± S.E. (A) of three independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05 or representative of three independent experiments (B).

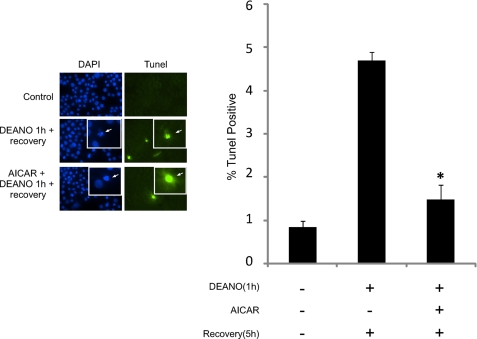

FIGURE 9.

AICAR attenuates β-cell death during recovery. INS832/13 cell were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 5-h incubation. Following these incubations, DNA damage was examined by TUNEL, and nuclei identified using DAPI; the inset is shown to display nuclear morphology. TUNEL-positive cells were quantified as a percentage of total (DAPI-stained) cells. Results are means ± S.E. of three independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05.

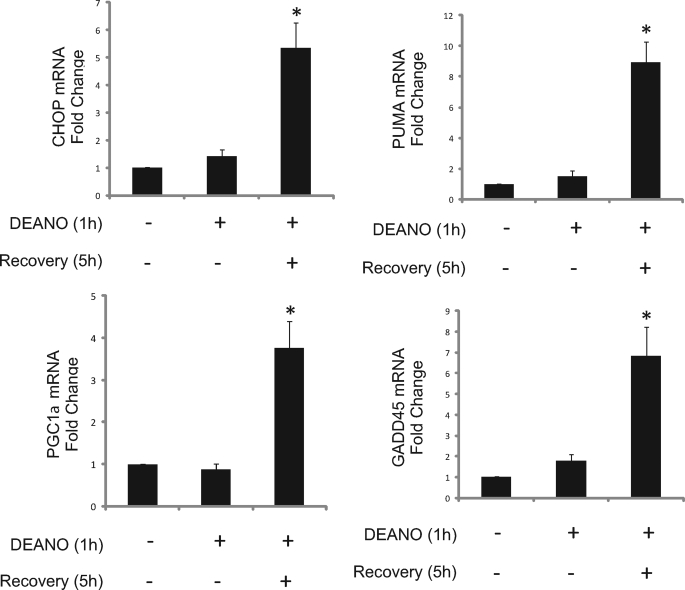

FIGURE 4.

Expression of survival and death genes during recovery. INS832/13 cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 5-h recovery incubation. Total RNA was isolated, and the mRNA accumulation of CHOP, PUMA, PGC1α, and GADD45, mRNA was determined by qRT-PCR. Results are means ± S.E. of 3–4 independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

Activation state of caspase-3 in response to nitric oxide. INS832/13 cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 5 h or for 5 h with camptothecin as a positive control for apoptosis. Following incubations, the level of caspase-3 enzymatic activity was measured (A) or cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 were measured by Western blot analysis (B). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

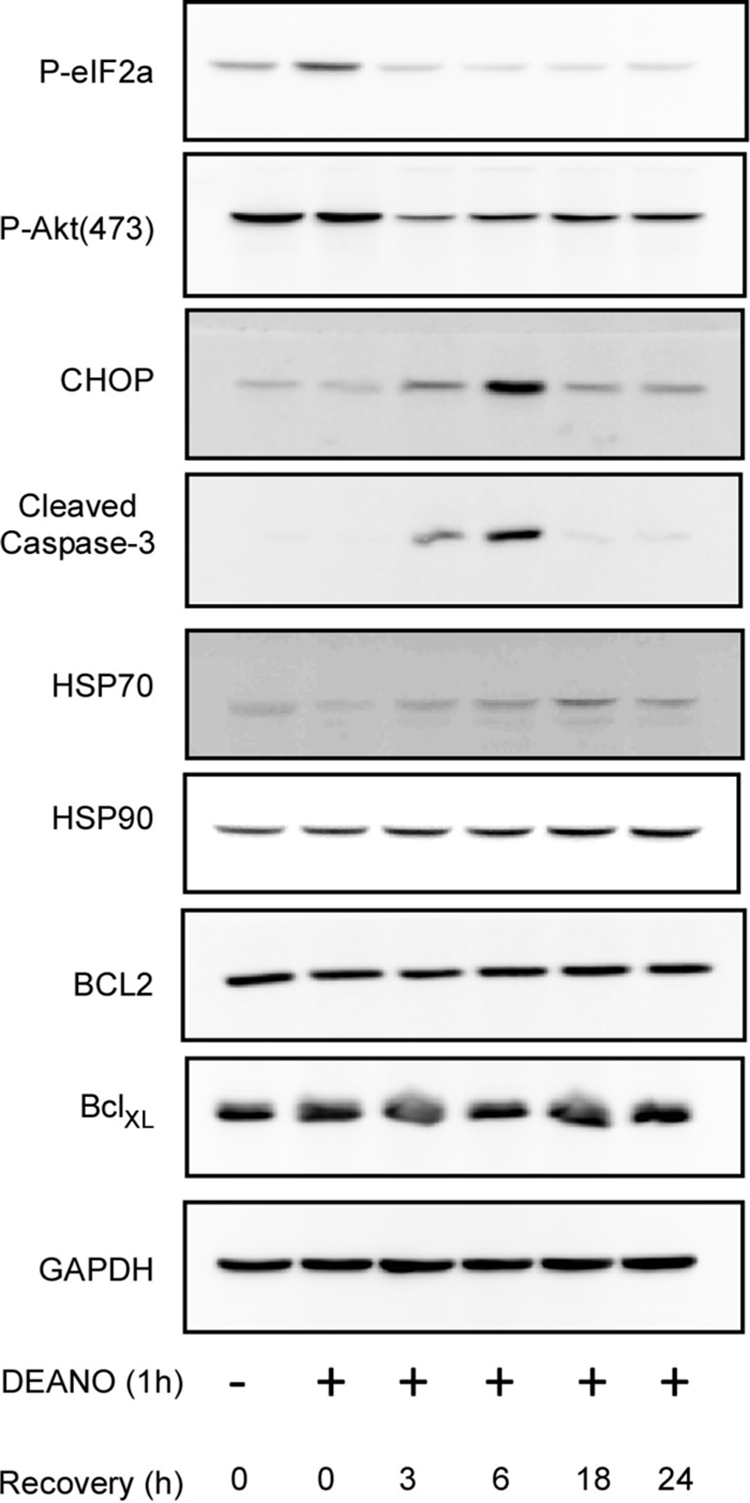

The Adaptive Response of β-Cells to Nitric Oxide

Whereas there is a small increase in caspase activity and low levels of caspase-3 cleavage following 1 h incubation with DEANO followed by an additional 5 h of incubation in the absence of DEANO, we have shown that these cells and islets have the ability to recover metabolic function and repair damaged DNA (13, 14, 28). To more thoroughly examine the effects of a 1-h incubation with DEANO, followed by washing and continued incubation in the absence of the nitric oxide donor for 0–24 h, the expression of a number of stress-responsive proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis were examined (Fig. 6). A rapid and transient phosphorylation of eIF2α was observed in response to nitric oxide treatment indicating that the cells were initially stressed. Early in the recovery, the accumulation of proteins associated with the induction of apoptosis (3- & 6-h post-DEANO treatment) was observed suggesting a pro-apoptotic environment. This includes the reduction in the phosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic factor Akt, increases in CHOP expression and low levels of caspase-3 cleavage. Later in the recovery process (16 & 24 h) phospho-eIF2α, Akt, CHOP, and cleaved caspase-3 all return to levels observed under basal conditions. We do not interpret these data to indicate that caspase-3 activation and associated apoptosis is reversible. These findings indicate that a small percentage (∼4.5%, Fig. 9) of the cells die in a caspase-dependent fashion, and the remaining cells have the ability to overcome the stress of the short exposure to nitric oxide. Consistent with this interpretation, proteins associated with protection such as HSP70 and HSP90 were elevated following 16 and 24 h after the DEANO treatment, whereas the levels of bcl2 and bclXL remain unchanged (Fig. 6). Taken together, these data suggest that nitric oxide mediates the induction of apoptosis in a small and limited population of β-cells (as evidenced by cleaved caspase-3); however, the vast majority of the cells survive the insult and up-regulate protective adaptive responses.

FIGURE 6.

Alterations in signaling during nitric oxide-induced damage and recovery. INS832/13 cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and continued incubation in the absence of DEANO for 0–24 h. The levels of phosphorylated eIF2α, and Akt, CHOP, and cleaved caspase-3 were examined by Western blot analysis as a measure for cell stress and apoptosis. HSP70, HSP90, Bcl2, and BclXL were examined by Western blot analysis as a measure of adaptation and cell survival. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

AMPK Promotes Reactivation of Mitochondrial Aconitase

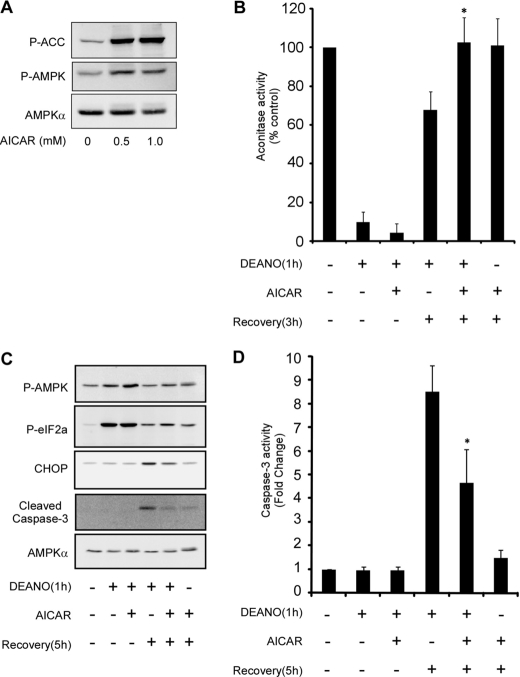

Considering the stress responsive activation of AMPK and its well established role in restoring and maintaining cellular homeostasis, we hypothesized that AMPK could promote recovery of metabolic function and attenuate apoptosis. In support of this hypothesis, data presented in Figs. 1 & 2 show that nitric oxide and IL-1 (in a nitric oxide-dependent manner) induce a transient activation of AMPK. To investigate if AMPK can modulate the recovery of oxidative metabolism the effects of the AMPK activator aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) on the recovery of mitochondrial aconitase was examined. INS832/13 cells respond as expected to AICAR with increased phosphorylation of ACC and AMPK (Fig. 7A). AICAR does not modify the inhibitory effects of a 1-h incubation with DEANO on INS832/13 cell aconitase activity, suggesting that AMPK activation does not influence the inhibitory actions of nitric oxide on β-cell oxidative metabolism. In contrast, AMPK activation by AICAR stimulates complete recovery of aconitase activity following removal of DEANO and continued culture for 3 h compared with 65% recovery in cells not treated with AICAR (Fig. 7B). Alone, 3 h of incubation with AICAR did not modify mitochondrial aconitase activity in INS832/13 cells. These data suggest that AMPK facilitates the functional recovery of oxidative metabolism in nitric oxide-treated β-cells.

FIGURE 7.

AICAR promotes recovery of aconitase activity and attenuates caspase-3 activation. INS832/13 cells were treated the indicated concentration of AICAR for 1 h. The cells were isolated and phosphorylated ACC, AMPK, and total AMPKα were determined by Western blot analysis (A). INS832/13 cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 3-h incubation. Both the DEANO exposure and recovery incubation were performed in the presence or absence of 1 mm AICAR as indicated. Following treatments, the cells were isolated, and mitochondrial aconitase activity was determined (B). Alternatively, phosphorylated AMPK, eIF2α, and total CHOP, cleaved caspase-3 and AMPKα were measured by Western blot analysis (C), and caspase-3 activity was measured under the same conditions (D). Results are means ± S.E. of three independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05.

AMPK Attenuates Caspase-3 Activation during Recovery from Nitric Oxide-induced Damage

Consistent with a protective role in enhancing β-cell recovery from nitric oxide-mediated damage, AMPK also appears to function in preventing the activation of caspase activity in response to DEANO. The expression of CHOP and cleavage of caspase-3 are elevated in INS832/13 cells treated for 1 h with DEANO followed by washing and an additional 5-h incubation in the absence of DEANO. Activation of AMPK using AICAR attenuates this increase in CHOP expression and cleavage of caspse-3. These changes are associated with an increase in the phosphorylation of eIF2α and, as expected, AMPK (Fig. 7C). Consistent with low levels of caspase-3 cleavage, there is an 8-fold increase in caspase-3 activity in INS832/13 cells treated with DEANO for 1 h, followed by washing and a 5-h recovery. Importantly, AMPK activation using AICAR attenuates this caspase activity by ∼50% (Fig. 7D).

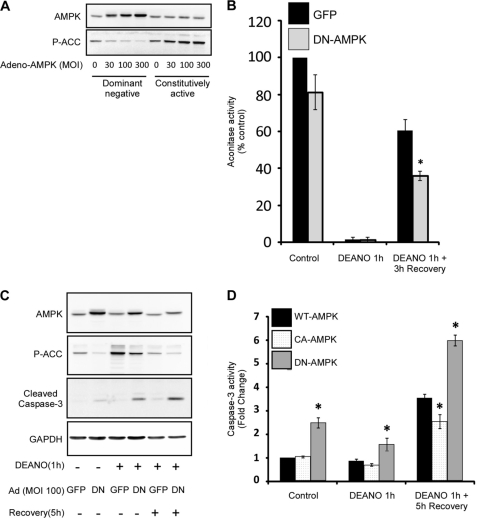

To confirm the pharmacological findings obtained using AICAR, the effects of modulating AMPK activity on the response of β-cells to nitric oxide was examined using adenoviral expression of dominant negative (DN) or constitutively active (CA) AMPK mutants. Transduction of INS832/13 cells with DN-AMPK results in a concentration-dependent inhibition in the phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC. In contrast, expression of CA-AMPK stimulates the concentration-dependent increase of ACC phosphorylation (Fig. 8A). To verify that AMPK regulates recovery of mitochondrial aconitase activity, cells were transduced with a GFP control virus or DN-AMPK. In cells expressing GFP, treatment with DEANO for 1 h suppressed aconitase activity and, following a 3-h recovery, aconitase activity was restored to ∼60% of the control levels. In cells expressing DN-AMPK, this recovery of aconitase activity was significantly attenuated (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of AMPK attenuates recovery of aconitase activity and promotes caspase-3 activation during recovery. INS832/13 cells were transduced with increasing amounts of adenovirus expressing dominant negative or constitutively active AMPK mutants. The cells were isolated 48 h later, and the levels of total AMPK and phosphorylated Ser-79-ACC were determined by Western blot analysis (A). The CA-AMPKγ is not recognized by the total AMPKα antibody, but is expressed as determined by the increased phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC. INS182/13 were transduced with GFP control virus or DN-AMPK at an MOI of 100, ∼40-h post-transduction cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 3-h incubation. Following treatments, the cells were isolated, and mitochondrial aconitase activity was determined (B). INS182/13 were transduced with GFP control virus or DN-AMPK at an MOI of 100, ∼40-h post-transduction cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 5-h incubation. The cells were then isolated, and the levels of AMPK, phosphorylated Ser-79-ACC, cleaved caspse-3, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis (C). INS832/13 cells were transduced with WT, CA, or DN-AMPK at an MOI of 100, ∼40-h post-transduction cells were treated for 1 h with 1 mm DEANO, or with DEANO followed by washing to remove the donor and an additional 5-h incubation. The cells were then isolated, and caspase-3 activity was then determined (D). Results are representative of or the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments with statistically significant differences; *, p < 0.05.

Consistent with modulation of aconitase recovery, expression of adenoviral AMPK mutants also influence caspase-3 activation. To examine the effects of nitric oxide on AMPK activity, INS832/13 cells were transduced with a GFP control virus or DN-AMPK followed by a 1-h incubation with DEANO, or a 1-h incubation with DEANO, followed by washing and a 5-h recovery incubation. In INS832/13 cells expressing DN-AMPK, basal and nitric oxide-stimulated ACC phosphorylation (following a 1-h incubation with DEANO) are attenuated indicating that DN-AMPK inhibits endogenous AMPK activation. Under these conditions, the inhibition of AMPK results in an increase in caspase-3 activation as determined by caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 8C) and caspase-3 activity (Fig. 8D). Consistent with an anti-apoptotic role for AMPK, expression of DN-AMPK for a prolonged period, 48 h, results in an increase in caspase-3 cleavage and caspase-3 activity, independent of the effects of nitric oxide. Using the CA-AMPK mutant, we show that the increase in caspase-3 activity in INS832/13 cells stimulated by a 1-h incubation with DEANO, followed by washing and 5-h recovery, is attenuated when compared INS832/13 cells expressing WT-AMPK and the DN-AMPK mutant (Fig. 8D). These data indicate that nitric oxide-induced AMPK activation suppresses caspase-3 activation.

To further assess the role of AMPK in caspase-mediated cell death, apoptosis was measured by TUNEL staining. Under control conditions less than 1% of the cells stained TUNEL-positive. Following a 1-h DEANO treatment and 5-h recovery in the absence of DEANO ∼4.5% of the cells are TUNEL-positive with condensed and fragmented nuclei consistent with apoptotic cell death (Fig. 9). Importantly, this modest level of TUNEL positivity correlates with the relatively low level of caspase-3 activity shown in Fig. 5. When AICAR is present during treatment and recovery, the number of TUNEL-positive cells is significantly reduced to near control levels (Fig. 9). These data indicate that AMPK can suppress caspase-mediated cell death during recovery from nitric oxide-induced damage.

DISCUSSION

Exposure of β-cells to proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 leads to extensive nitric oxide-dependent cellular damage and ultimately cell death. However, β-cells maintain the limited ability to recover from cytokine or nitric oxide induced damage (13, 14). The role of AMPK in this recovery process was previously unknown. The current study demonstrates that AMPK activation in response to IL-1 in primary rat islets is nitric oxide-dependent. The IL-1-induced activation of AMPK was found to be relatively early (12–24 h) and transient following IL-1 treatment. Furthermore, by augmenting AMPK activation in response to the nitric oxide donor DEANO we were able to reveal that AMPK promotes cellular recovery and attenuates caspase-3 activation following nitric oxide-induced damage.

Our data suggest that AMPK plays an integral role in preventing the induction of apoptosis and facilitating β-cell recovery following exposure to nitric oxide. Whereas we estimate that less than 5% of the cells undergo caspase-dependent cell death during recovery from nitric oxide-induced damage, the exact level of cell death is difficult to assess. Measurements of cell death typically rely on metabolic activity or DNA integrity, cellular targets that are damaged by nitric oxide. This makes it difficult to accurately discriminate between cell death and reversible nitric-oxide induced damage. The transient nature of AMPK activation is likely to be essential for the AMPK-mediated blockade of capase-3 activation and apoptotic cell death during recovery from nitric oxide-induced damage. Our findings are in line with previous findings that AMPK activation promotes restoration of cellular energy homeostasis and that physiologically the AMPK pathway is antiapoptotic (16, 29, 30, 31). Furthermore, it has also been demonstrated that AICAR, in a β-cell line, attenuates CHOP expression and apoptosis induced by hyperglycemia (32) However, prolonged overactivation of AMPK by AICAR or the anti-diabetic drug Metformin has been reported to drive β-cell apoptosis (33, 34). We have also observed that prolonged activation (48 h) through the use of AICAR will stimulate caspase-3 activation in islets.4 The data presented in this study do not contradict previous reports indicating AMPK activation in islets following 48 h of treatment with cytokines (IL-1, INFγ, TNFα) promotes apoptosis (15). At these longer time points β-cells are committed to cell death (27). Under these prolonged cytokine exposures, AMPK may function to preserve enough ATP to support apoptosis.

The molecular mechanisms regulating the suppression of apoptosis are likely to be multifaceted. AMPK activation can suppress protein synthesis through phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 kinase (35) and through the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway (30) thus preserving energy and decreasing the burden from the unfolded nascent polypeptides. Importantly, the AMPK activation observed in our study was transient allowing for the reactivation of protein synthesis that is likely essential for survival. Additionally, we observed a transient decrease in the activation associated phosphorylation of Akt and Akt has been found to work in opposition of AMPK in the regulation of TOR signaling (36). Thus, the observed transient activation of AMPK and inactivation of Akt might promote initial survival whereas the later inactivation of AMPK and reactivation of Akt is essential for long term survival. Additionally, recent evidence indicates that activation of AMPK can increase the NAD+/NADH ratio increasing the activity of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SirT1 (37). SirT1 in turn regulates a host of proteins including many transcription factors known to promote the expression of cytoprotective genes (38).

The finding that nitric oxide induces damage and also activates a protective recovery and adaptation response is consistent with our previous findings in β-cells (14) as well as findings in other cell types (39). This dichotomous role of nitric oxide is similar to the well studied ER stress-induced unfolded protein response (UPR). In this case activation of the UPR is initially a protective and adaptive response however, if the stress remains, prolonged activation will lead to apoptosis (40). This suggests that there are mechanisms that suppress apoptosis while the cell repairs and eliminates damaged constituents. Our results suggest that AMPK is an important component to the overall response to nitric oxide; early transient activation promotes recovery and suppresses apoptosis, whereas prolonged activation can promote apoptosis. We did not test if AMPK directly influences changes in gene expression that allow for adaptation, but the data suggest that AMPK suppresses caspase activation to allow the adaptive response to prevail. This also raises the intriguing possibility that AMPK plays a broader role in recovery from cellular insults. Additional studies are needed to determine the role of AMPK in cellular recovery and adaptation to insults beyond nitric oxide.

IL-1-induced activation of AMPK is nitric oxide-dependent however the mechanism of activation is unknown. It is likely that multiple mechanisms including an increase in intracellular AMP levels and an increase in LKB1-mediated phosphorylation participate in AMPK activation in response to nitric oxide. It has been previously demonstrated that PKCζ can phosphorylate LKB1 to promote the interaction between LKB1 and AMPK in response to peroxynitrite, suggesting that LKB1 may participate in free radical-induced activation of AMPK (41).

Overall, it is likely that the level and duration of AMPK activation will have a profound impact on cellular fate. Our results suggest that a transient activation of AMPK might facilitate cellular repair and prolong survival following cellular damage. This is of potential therapeutic value as AMPK could be pharmacologically activated in islets during transplantation to promote recovery from the damage sustained during isolation and engraftment thus reducing the number of islets needed for successful transplantation.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Richard Jope (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for generously providing the adenoviral GFP.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health-UAB program in Immunology Training Grant T32AI007051-31A1 (to G. P. M.) and Grants R01-DK52194 and AI 44458 (to J. A. C.).

J. A. Corbett, unpublished observation.

- IL

- interleukin

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- AICAR

- 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- DEANO

- (Z)-1(N,N-diethylamino) diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate

- NMMA

- NG-monomethyl-l-arginine

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor α

- INFγ

- interferon γ

- iNOS

- inducible nitric-oxide synthase

- eIF2α

- eukaryotic initiation factor 2α

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- CaMKK

- calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GADD45

- growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 45

- PGC1α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1α

- PUMA

- p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis

- CHOP

- C/EBP-homologous protein

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- WT

- wild type

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gepts W. (1965) Diabetes 14, 619–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tisch R., McDevitt H. (1996) Cell 85, 291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacy P. E., Finke E. H. (1991) Am. J. Pathol. 138, 1183–1190 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohmeier H. E., Tran V. V., Chen G., Gasa R., Newgard C. B. (2003) Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 27, Suppl. 3, S12–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendtzen K., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Nerup J., Nielsen J. H., Dinarello C. A., Svenson M. (1986) Science 232, 1545–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbett J. A., Wang J. L., Sweetland M. A., Lancaster J. R., Jr., McDaniel M. L. (1992) J. Clin. Invest. 90, 2384–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham J. M., Green I. C. (1994) Growth Regul. 4, 173–180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess D. T., Matsumoto A., Kim S. O., Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbett J. A., Wang J. L., Hughes J. H., Wolf B. A., Sweetland M. A., Lancaster J. R., Jr., McDaniel M. L. (1992) Biochem. J. 287, 229–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fehsel K., Jalowy A., Qi S., Burkart V., Hartmann B., Kolb H. (1993) Diabetes 42, 496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koeck T., Corbett J. A., Crabb J. W., Stuehr D. J., Aulak K. S. (2009) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 484, 221–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comens P. G., Wolf B. A., Unanue E. R., Lacy P. E., McDaniel M. L. (1987) Diabetes 36, 963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbett J. A., McDaniel M. L. (1994) Biochem. J. 299, 719–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarim A. L., Nishimoto S. Y., Weber S. M., Corbett J. A. (2003) Endocrinology 144, 3415–3422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riboulet-Chavey A., Diraison F., Siew L. K., Wong F. S., Rutter G. A. (2008) Diabetes 57, 415–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardie D. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong S. P., Leiper F. C., Woods A., Carling D., Carlson M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8839–8843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawley S. A., Boudeau J., Reid J. L., Mustard K. J., Udd L., Mäkelä T. P., Alessi D. R., Hardie D. G. (2003) J. Biol. 2, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawley S. A., Pan D. A., Mustard K. J., Ross L., Bain J., Edelman A. M., Frenguelli B. G., Hardie D. G. (2005) Cell Metab. 2, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly C. B., Blair L. A., Corbett J. A., Scarim A. L. (2003) Methods Mol. Med. 83, 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green L. C., Wagner D. A., Glogowski J., Skipper P. L., Wishnok J. S., Tannenbaum S. R. (1982) Anal. Biochem. 126, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delaney C. A., Green M. H., Lowe J. E., Green I. C. (1993) FEBS Lett. 333, 291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh N. P., McCoy M. T., Tice R. R., Schneider E. L. (1988) Exp. Cell Res. 175, 184–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrasco R. A., Stamm N. B., Patel B. K. (2003) BioTechniques 34, 1064–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minokoshi Y., Alquier T., Furukawa N., Kim Y. B., Lee A., Xue B., Mu J., Foufelle F., Ferré P., Birnbaum M. J., Stuck B. J., Kahn B. B. (2004) Nature 428, 569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawley S. A., Davison M., Woods A., Davies S. P., Beri R. K., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27879–27887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarim A. L., Heitmeier M. R., Corbett J. A. (1997) Endocrinology 138, 5301–5307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes K. J., Meares G. P., Chambers K. T., Corbett J. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27402–27408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw R. J., Kosmatka M., Bardeesy N., Hurley R. L., Witters L. A., DePinho R. A., Cantley L. C. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3329–3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoki K., Zhu T., Guan K. L. (2003) Cell 115, 577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terai K., Hiramoto Y., Masaki M., Sugiyama S., Kuroda T., Hori M., Kawase I., Hirota H. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9554–9575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyblom H. K., Sargsyan E., Bergsten P. (2008) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 41, 187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kefas B. A., Heimberg H., Vaulont S., Meisse D., Hue L., Pipeleers D., Van de Casteele M. (2003) Diabetologia 46, 250–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kefas B. A., Cai Y., Kerckhofs K., Ling Z., Martens G., Heimberg H., Pipeleers D., Van de Casteele M. (2004) Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horman S., Browne G., Krause U., Patel J., Vertommen D., Bertrand L., Lavoinne A., Hue L., Proud C., Rider M. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1419–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoki K., Li Y., Zhu T., Wu J., Guan K. L. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantó C., Gerhart-Hines Z., Feige J. N., Lagouge M., Noriega L., Milne J. C., Elliott P. G., Puigserver P., Auwerx J. (2009) Nature 458, 1056–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dali-Youcef N., Lagouge M., Froelich S., Koehl C., Schoonjans K., Auwerx J. (2007) Ann. Med. 39, 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borniquel S., Valle I., Cadenas S., Lamas S., Monsalve M. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 1889–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ron D., Walter P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie Z., Dong Y., Zhang M., Cui M. Z., Cohen R. A., Riek U., Neumann D., Schlattner U., Zou M. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6366–6375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]