Abstract

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade activates genes that allow cells to adopt particular identities throughout development. In adult self-renewing tissues like intestine and blood, activation of the Wnt pathway maintains a progenitor phenotype, whereas forced inhibition of this pathway promotes differentiation. In the lung alveolus, type 2 epithelial cells (AT2) have been described as progenitors for the type 1 cell (AT1), but whether AT2 progenitors use the same signaling mechanisms to control differentiation as rapidly renewing tissues is not known. We show that adult AT2 cells do not exhibit constitutive β-catenin signaling in vivo, using the AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mouse, or after fresh isolation of an enriched population of AT2 cells. Rather, this pathway is activated in lungs subjected to bleomycin-induced injury, as well as upon placement of AT2 cells in culture. Forced inhibition of β-catenin/T-cell factor signaling in AT2 cultures leads to increased cell death. Cells that survive show reduced migration after wounding and reduced expression of AT1 cell markers (T1α and RAGE). These results suggest that AT2 cells may function as facultative progenitors, where activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling during lung injury promotes alveolar epithelial survival, migration, and differentiation toward an AT1-like phenotype.

Keywords: Cell/Epithelial, Cell/Differentiation, Diseases, Organisms/Mouse, Tissue/Organ Systems/Lung, Developmental Pathways, Wnt Signaling

Introduction

Alveolar epithelial cells Type 1 (AT1)3 and -Type 2 (AT2) are the two major cell types that form the lung air barrier. The type 1 cell is distinguished by its flattened shape and large surface area, which presumably facilitates the diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide. The type 2 cell produces lipoprotein complexes, known as surfactants, which reduce surface tension, among other functions (1–3). Given the number of alveoli and their extensive surface area, AT1 and -2 cells are the most abundant epithelial cell types in the lung. Thus, understanding the homeostatic mechanisms that allow these cells to differentiate and manifest their adult phenotypes is important to lung physiology (4, 5).

Upon alveolar injury, AT1 cells die and restoration of the alveolar epithelium is thought to be driven by the expansion of AT2 cells (reviewed in Ref. 6). This historical view of AT2 cells as “progenitors” for AT1 cells is based on several findings: their proliferation after lung injury (7), radioactive tracing experiments revealing that tritiated thymidine is first incorporated into AT2 cells and subsequently observed in cells with type 1 features (8), and the longstanding observation that AT2 cells acquire AT1-like characteristics upon being placed in culture (9–12). Whether signaling pathways essential for lung development can re-program alveolar epithelial identities, after injury to restore adult lung structure and function, is an active area of investigation.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is one of the core signal transduction pathways used reiteratively throughout development and adult tissue homeostasis to instruct cells to adopt particular fates. The canonical Wnts are secreted lipoglycoproteins that control cell fate specification by activating a transcription complex that contains a DNA-binding factor known as lymphocyte enhancer factor/T-cell factor (TCF), and the dual function signaling/adhesion protein, β-catenin. In this complex, β-catenin serves as an obligate co-activator through its ability to recruit components that promote chromatin remodeling and transcriptional initiation/elongation (review in Ref. 13).

Wnts activate β-catenin signaling by inhibiting a degradation mechanism that serves to keep the cytosolic “signaling” pool of β-catenin at low levels. In the absence of Wnt, the N terminus of β-catenin is constitutively phosphorylated by casein kinase 1α and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (14). This phosphorylation allows β-catenin to be recognized by a specific E3 ligase, which catalyzes the ubiquitylation and rapid degradation of cytosolic β-catenin (15). During Wnt activation, GSK3β activity is inhibited, allowing β-catenin to escape this degradation mechanism and accumulate in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments (16). Accumulation of β-catenin that is specifically unphosphorylated at these GSK3β sites is known to be critical for β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription (17).

It is now appreciated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling exerts variable effects on cell fate specification in adult tissues. In self-renewing tissues such as intestine, β-catenin/TCF transcription maintains the de-differentiated, progenitor/stem cell fate (18–20), whereby inhibition of β-catenin/TCF signaling drives the differentiation of intestinal progenitors into enterocytes. In contrast, β-catenin/TCF signaling promotes the differentiation of paneth cells, which are located at the base of intestinal crypts (21). Additionally, a gradient of Wnt signaling existing along the porto-central axis in adult liver controls the expression of metabolic genes (e.g. glutamate synthetase) required for ammonia detoxification (22, 23). Taken altogether, Wnt/β-catenin signaling drives de-differentiation, differentiation, and metabolic cell fate decisions in various tissues, leading to a general view that the genes regulated by β-catenin/TCF must be cell type- and context-dependent (reviewed in Ref. 24).

In the context of these aforementioned models, the precise roles for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in lung development and adult homeostasis are incompletely understood. Targeted loss of β-catenin in SP-C-expressing cells blocks distal lung morphogenesis (25), demonstrating the requirement of epithelial β-catenin signaling in the formation of alveolar cell types and structures. Conversely, overexpression of a non-degradable form of β-catenin using the Clara-cell secretory protein promoter, CCSP, drives hyper-proliferation and loss of airway septation (26). More recently, β-catenin signaling has been shown to expand the variant Clara (stem) cell pool after naphthalene-induced lung injury (27), although it may not be absolutely required (28).

Despite evidence that AT2 cells may serve as progenitors for AT1 cells, the extent to which canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling controls the survival and differentiation of these cell types is not yet known. In this study, we asked whether AT2 cells are the type of progenitor that exhibits constitutive Wnt/β-catenin signaling, or instead manifest signaling upon injury. Using primary AT2 cells that show activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling upon being placed in culture, we also addressed the consequences of reducing this activation toward the survival, migration, and differentiation characteristics of AT2 cells. Our findings indicate that the isolation and short term culturing of primary AT2 cells may recapitulate key aspects of an in vivo response to alveolar lung injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Alveolar epithelial type 2 cells (AT2s) are isolated from pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–225 g) by the Pulmonary Core Facility at Northwestern University as previously described (29, 30). Briefly, lungs are perfused via the pulmonary artery, lavaged, and digested with 4 units/ml elastase (Worthington Biochemicals) for 20 min at 37 °C. Tissue is minced and filtered through sterile gauze followed by 150- and 15-μm nylon mesh (Sefar). The crude cell suspension is purified by differential adherence of non-AT2 cells to rat immunoglobulin G-coated dishes (Sigma). AT2 cells are cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 4.5 gm/liter glucose, l-glutamine with sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), and penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech). AT2 viability is typically >93% as determined by exclusion of Trypan blue stain. Purity is >90% by staining for lamellar bodies with Papanicolaou stain. The day of isolation and plating is designated culture Day0.4

Rat alveolar epithelial type I cells (AT1s) are isolated similarly using twice the concentration of elastase (31, 32). In brief, AT1s are isolated from lung cells remaining after differential adherence to rat IgG-coated dishes by positive immunoselection with a T1α monoclonal antibody. Cells are then incubated with rat anti-mouse IgG-conjugated magnetic beads prior to magnetic selection (Dynal Biotech, Invitrogen). AT1 cells are released from the magnetic beads using DNase I-releasing buffer. The viability of AT1 cells in Fig. 1 was >94% as determined by exclusion of Trypan blue stain and contained 86% AT1 cells and <2% AT2 cells, as analyzed by cytocentrifuged cell preparations stained with antibodies specific for aquaporin-5 (AT1-specific) and SP-C (AT2-specific). Murine AT2 cells were isolated from AXIN2+/+ or +/LacZ C57BL/6 mice using a protocol similar to that used for rats except that cells were purified by negative immunoselection using magnetic beads followed by differential adherence to anti-CD90 coated dishes. Cell viability was >95% and purity ∼87% with alveolar macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts (all vimentin positive) comprising the remaining 13% (33). HEK293T and MDCK cells are obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 4.5 gm/liter glucose, l-glutamine with sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bioproducts) and penicillin/streptomycin. All cells are maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37 °C.

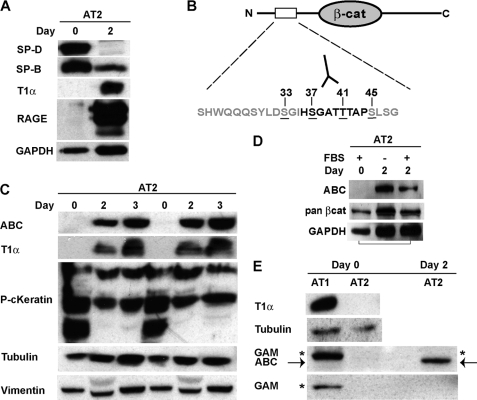

FIGURE 1.

Expression of the signaling form of β-catenin increases during trans-differentiation of AT2 cells in culture. AEC types 1 and 2 were isolated from rat lungs, and total protein was extracted immediately after isolation (Day0) or after 2–3 days of culture. Activated β-catenin (ABC), T1α and RAGE (AT1 markers), pancytokeratin (epithelial marker), SP-D and SP-B (AT2 markers), vimentin (fibroblast marker), and β-tubulin and GAPDH (loading controls) were detected by Western blot as described under “Materials and Methods.” A, AT2 cells express SP-D and SP-B on Day0, but begin to express T1α and RAGE by Day2. B, schematic of the N-terminal casein kinase 1α/GSK3β phosphorylation sites in β-catenin. ABC (mAb 8E7) specifically recognizes Ser-37 and Thr-41 in the unphosphorylated state (17). C, freshly isolated AT2 do not express ABC or T1α, but both proteins are up-regulated by Day2 and Day3 in culture. Platings from different cell isolates are shown in duplicate. D, detection of ABC in AT2 cells is not dependent on serum. E, freshly isolated AT1 express T1α, but not ABC. Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody recognizes a nonspecific band (asterisk) that closely co-migrates with ABC (arrow) in AT1, but not AT2 isolates. Because isolation of type 1 cells relies on positive selection with the T1α monoclonal antibody, we suspect the nonspecific band is due unreduced immunoglobulin.

Adenoviral Constructs

Adeno-S37A-β-catenin-HA (HA-hemagglutinin epitope tag) was kindly provided by Jan Kitajewski (Columbia University (34)); Adeno-DKK1-GFP by Tong Chuan He (University of Chicago); Myc-ICAT cDNA by Tetsu Akiyama (Japan) and re-engineered by Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA) to encode a bicistronic mRNA that translates both Myc-ICAT and GFP proteins (Adeno-ICAT (Myc)-IRES-GFP). The Adeno-CMV-GFP control virus was purchased from Vector Biolabs, which also prepared in high titer viral solutions (1010–1012 plaque forming units/ml) of these viruses. Infection efficiency of >90% was confirmed by visualizing GFP expression in living cells or the HA tag by immunofluorescence analysis.

Antibodies and Immunoblots

The following antibodies were used for immunoblot, immunohistochemical, or immunofluorescence analysis: mouse monoclonal anti-active-β-catenin clone 8E7 (ABC, Millipore), rabbit polyclonal anti-β-catenin (06-734, Millipore, raised against the unphosphorylated peptide, CGGSYLDSGIHSGATTTAPSLSGK, corresponding to the consensus GSK3 phosphorylation site of human β-catenin (amino acids 29–49), mouse monoclonal anti-β-catenin clone 14 (BD Transduction, referred to as pan-β-catenin in this study), rabbit polyclonal anti-Wnt 1 (Abcam, #5251), goat polyclonal anti-SP-D (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-SP-B (Leland Dobbs), mouse monoclonal anti-T1α (kindly provided by Mary Williams), rabbit polyclonal anti-RAGE (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-CC10 (FL-96, SC-25555, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin clone TUB 2.1 (Sigma), mouse monoclonal anti-Vimentin (Sigma), mouse monoclonal anti-Pan-cytokeratin (Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit monoclonal anti-LRP6 (Cell Signaling), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-LRP6 (Ser 1490, Cell Signaling), mouse monoclonal anti-HA clone 12CA5 (Abgent), mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc clone 9E10 (Sigma), and goat anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, and rabbit anti-goat IgG-horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad).

Cells were lysed in standard radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Protein content was assayed using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to BioTrace NT nitrocellulose (Pall). Membranes were stained with Ponceau S solution to evaluate protein transfer. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk/Tris-buffered saline/Tween and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in 5% milk/Tris-buffered saline/Tween. Immunoblots were developed in ECL solution (Amersham Biosciences) and exposed to chemiluminescent-compatible film (Hyperfilm-ECL, Amersham Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence, Immunohistochemistry, and X-gal Staining

Rat AT2 cells were plated onto glass coverslips (Day0), fixed in ice-cold methanol (Day3) and processed for immunofluorescence using standard procedures with the ABC and β-catenin (primary), and AlexaFluor-conjugated goat anti-mouse-IgG (Molecular Probes, secondary). Cells were imaged using a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope. Immunoperoxidase experiments were performed on rat lungs inflated and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for 2 h at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed in boiling sodium citrate buffer for 1–2 min, followed by antibody incubations and signal amplification with a streptavidin/biotin system (Vector Laboratories). Multispectral Imaging was carried out using the Nuance 2TM system (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Inc.). This technique facilitates co-localization studies between abundant cell markers (e.g. SP-C in AT2 cells) versus less abundant stains (e.g. X-gal-labeled cells) (35). For staining of AXIN2-β-galactosidase reporter mice, lungs were instilled with freshly made fixative (0.2% w/v glutaraldehyde/2% w/v paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4) for 20 min at 4 °C. Fixative was removed by lavage with PBS followed by instillation of X-gal solution (20 mm potassium ferrocyanide, 20 mm potassium ferricyanide, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mg/ml X-gal, 0.01% deoxycholic acid, and 0.02% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.4). X-gal staining proceeded overnight at 37 °C. Lungs were again lavaged with PBS before instillation of 0.4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. Lungs are embedded in paraffin for 5-μm sectioning by the Pathology Core at Northwestern. For staining of AT2 cells isolated from AXIN2+/LacZ mice, Day3 AT2 cells from AXIN2+/+ (control) and AXIN2+/LacZ (reporter) mice were fixed (3% paraformaldehyde/0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4) for 10 min at room temperature and processed for X-gal staining as above. Colorimetric development of X-gal staining was allowed to proceed for 30 h in a 37 °C ambient air incubator.

Transfections and β-Catenin/TCF Reporter Assay

Rat AT2 cells (1.5 × 106/well (903 mm2)) were transfected on Day2 with 1 μg of Super8-TOPflash (containing 8 TCF-consensus binding sites) or 1 μg of Super8-FOPflash (8 mutant TCF-binding sites) reporter plasmids (kindly provided by Randall Moon, University of Washington, Seattle) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). A thymidine kinase-Renilla plasmid (0.1 μg) was also included to normalize luciferase values to the efficiency of transfection. Quantification of β-catenin/TCF signaling was also readily observed with the original 4× TOPflash reporter (kindly provided by H. Clevers, Utrecht, Netherlands), although this reporter plasmid manifested a higher baseline activity than the Super8, presumably due to differences in the minimal promoter regions (c-fos for the 4× TOP/FOPflash versus the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter for the Super8 reporter). AT2 cells were solubilized on Day4 using the Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega), and luciferase activity was quantified using a microplate dual-injector luminometer (Veritas).

LDH Cell Death Assay

5 × 105 rat AT2 cells and 3 × 105 MDCK cells plated on 12-well dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-10% fetal bovine serum were infected on Day0 with 5, 10, or 20 plaque forming units/cell of Ad-GFP, Ad-ICAT-GFP, Ad-S37A-β-cat, or Ad-Bcl-XL (kindly provided by Navdeep Chandel, Northwestern University). Ad-GFP was added as needed to equalize total adenoviral load. 1 mm staurosporine was used as a positive control for cell death (data not shown). On Day3, media was collected from wells. Remaining attached cells were incubated with media containing 2% Triton X-100 to calculate the percentage of total lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the media. LDH activity was measured in 96-well plates using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche Applied Science) according to manufacturer directions. A490 was read using a Versamax microplate reader and software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). All infections were performed in triplicate. Experiments were repeated three times and averaged, and data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

Scratch-wound Assay

2 × 106 rat AT2 cells were infected on Day0 with 20 plaque forming units/cell of Ad-GFP, Ad-ICAT-GFP, or Ad-S37A-β-cat and plated in a 35-mm plate. On Day2, cells at ∼90% confluency were scratched with a 200-μl sterile pipette tip and then photographed at 0 and 24-h time points. Wound surface area was quantified from captured images using Metamorph (Molecular Devices) analysis software. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was used throughout the assay. Adenoviral infection efficiency was >95% and verified by GFP or HA expression for the respective constructs.

Quantification of mRNA

Total RNA was extracted from Day0 and Day2 rat AT2 cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer instructions. First strand cDNA was reverse transcribed from equal amounts of total RNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Specific primers for amplification of the rat AXIN2 message: forward primer (FP), 5′-TGGTGCATACCTCTTCCGGACTTT-3′; reverse primer (RP), 5′-TTTCCTCCATCACCGCCTGAATCT-3′; and for mouse AXIN2: (FP) 5′-ACCTCAAGTGCAAACTCTCACCCA-3′ and (RP) 5′-AGCTGTTTCCGTGGATCTCACACT-3′. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix according to the manufacturer instructions (Bio-Rad). PCR was carried out in 96-tube plates using the MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System and software (Bio-Rad). All reactions were done in triplicate with negative controls. Experiments were repeated at least twice on different AT2 isolates, and data are reported as the mean ± S.D. GAPDH was used as the internal control. The relative change in gene expression was calculated using the 2ΔΔCt method.

Bleomycin-induced Lung Injury

C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old and weighing at least 20 g) were treated with a single intratracheal injection of 50 μl of saline or bleomycin (0.075 unit in 50 μl of saline per 20-g mouse (3.75 units/kg), Teva Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA). Following intubation, the bleomycin or saline was administered by direct instillation into the angiocath (two 25-μl aliquots, 2 min apart) using a Hamilton syringe. The mice were gently rotated (10 s each side) between aliquots, to facilitate dispersal of the reagent. After 6 days, the lungs were harvested for RNA extraction. A 20-gauge angiocath was sutured into the trachea, the lungs and heart were removed en bloc, and the lungs were inflated to 15 cm of H2O. Total RNA was extracted from tissue using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protocols were approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee. The AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mouse (C57BL/6 background) replaces one copy of the AXIN2 (also known as conductin) coding region with an NLS-lacZ knocked in-frame following the AXIN2 start codon (36). The mouse was purchased through the European Mouse Mutant Archive (EM:01789 and C57BL/6N).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni multiple comparison test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical calculations were performed using Prism (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Endogenous Activation of β-Catenin/TCF Signaling Activity in AT2 Cultures

Freshly isolated adult rat AT2 cells express established markers of type 2 cell differentiation, such as surfactant proteins B and D (SP-B and -D). After 2 days in culture, these cells lose the expression of AT2 markers and up-regulate markers of type 1 cell differentiation, such as T1α and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (37, 38) (Fig. 1A). Using an antibody that detects the transcriptionally active form of β-catenin (active B-catenin, or ABC) (17, 39), we show that ABC was not present in freshly isolated AT2 cells (Fig. 1, C and D, Day0), but rather is robustly up-regulated by Day2 in culture, correlating with the acquisition of type 1 markers, such as T1α and RAGE (Fig. 1C and not shown). This up-regulation is specific to the signaling form of β-catenin, which is increased relative to the total pool of β-catenin and does not require the presence of serum in the media (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S1B). The signaling form of β-catenin is also not present in freshly isolated, fully differentiated AT1 cells (Fig. 1E).

The presence of ABC reflects bona fide signaling activity, because AT2 cultures show activation of a widely used β-catenin/TCF Optimal Promoter reporter plasmid, TOP (Fig. 2A). This luciferase activity is specific, because co-transfection with a known inhibitor of the β-catenin/TCF binding interaction, ICAT (inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF (40)), strongly reduces reporter activation. Similarly, the endogenous target gene and negative feedback regulator of β-catenin/TCF signaling, AXIN2 (41), is strongly up-regulated in Day2 versus Day0 AT2 cultures by quantitative PCR (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, AXIN2 expression diminishes as AT2 monolayers mature (Day7 and Day14 (supplemental Fig. S1)), through a mechanism that allows cell-cell adhesion to limit Wnt/β-catenin signaling by promoting faster turnover of the signaling pool of β-catenin (42). Activation of β-catenin signaling in AT2 cultures does not appear to be limited to a small subpopulation of contaminating cell types, because the signaling form is detected throughout the alveolar epithelial monolayer (Fig. 2C), and we do not observe a small population of cells that exhibit strong cytoplasmic/nuclear β-catenin staining (not shown). Lastly, AT2 cells isolated from AXIN2+/LacZ reporter, but not littermate-matched control mice (AXIN2+/+), show up-regulation of β-galactosidase as evidenced by perinuclear X-gal staining (Fig. 2D) (43). Altogether, these data suggest that β-catenin/TCF signaling becomes activated upon placing AT2 cells in culture.

FIGURE 2.

AT2 cell cultures exhibit endogenous activation of β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription. A, dual luciferase reporter assay of AT2 cells transiently transfected with TOP- or FOPflash reporter constructs and Renilla with and without FLAG-ICAT on Day2 of culture and assayed on Day4. Transfections are performed in triplicate and expressed as relative light units normalized to Renilla activity. Results are mean values of four independent experiments ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. B, qRT-PCR demonstrating increased mRNA expression of β-catenin/TCF target gene, AXIN2, in Day2 compared with Day0 cultures. The Day0 versus Day2 comparison was performed on three independent AT2 isolations, and the results are mean change compared with Day0 ± S.D. *, p < 0.05. C, immunodetection of activated β-catenin (ABC) in AT2 cells at Day4 reveals junctional (arrows) and nuclear (arrowheads) staining throughout the monolayer. Goat-anti-mouse-IgG (GAM) secondary control is shown on left. The junctional forms of ABC comprise cadherin- and destruction complex-associated forms (42). The nuclear staining can be unspecific as described (70). D, Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation in mouse AT2 cells isolated from AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mice, but not AXIN2+/+ mice. Colorimetric detection of β-galactosidase activity is evidenced by conversion of X-gal substrate into an insoluble blue precipitate (arrowheads). Note that the NLS-β-galactosidase fusion protein can be mainly localized at the nuclear periphery (43).

Activation of β-Catenin Signaling in AT2 Cultures Is at the Level of the Wnt Co-receptor Complex

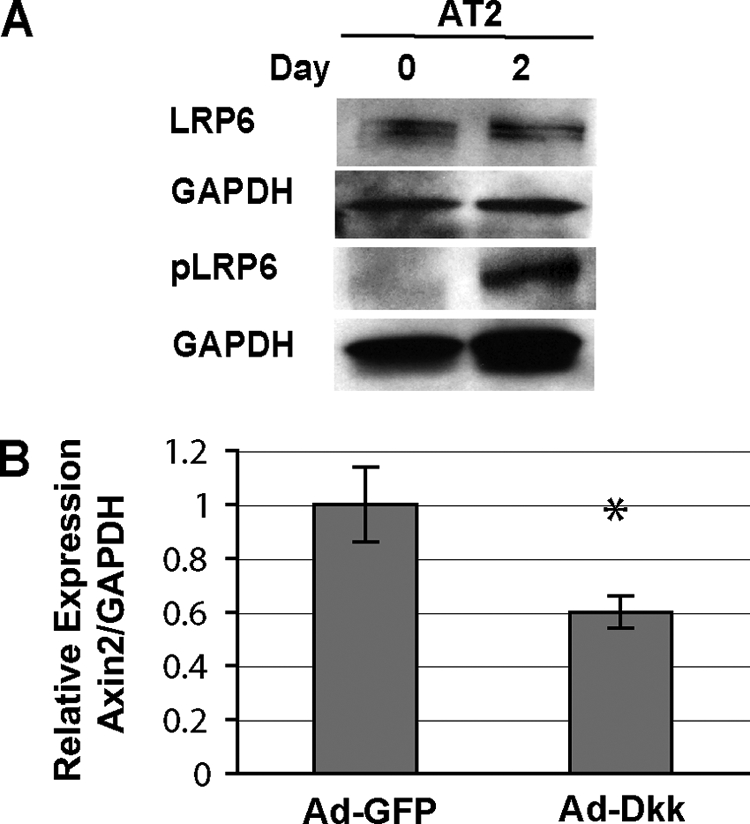

Using a phospho-specific antibody that recognizes residues in the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein cytoplasmic domain that become phosphorylated as a consequence of Wnt activation (44), we found that Day2 AT2 cells exhibit higher levels of phospho-LRP6 than freshly isolated, Day0 cells even though total LRP6 levels remained constant (Fig. 3A). Because AXIN2 expression can be significantly attenuated by overexpressing the extracellular Wnt pathway inhibitor, Dickkopf 1 (DKK1) (Fig. 3B), these data indicate that the up-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling observed in AT2 cell cultures is likely due a Wnt or Wnt-like ligand.

FIGURE 3.

β-Catenin signaling activation in AT2 cells is robust and at the level of the LRP Wnt co-receptor complex. A, LRP6 is phosphorylated in Day2, but not Day0 AT2 cultures. Total protein lysates from AT2 cells were immunoblotted for LRP6, phosphorylated LRP6, and GAPDH loading control. B, qRT-PCR of AXIN2 mRNA expression from AT2 cells infected with Adeno-GFP and Adeno-DKK-GFP on Day0 and assayed on Day2. Results are mean values of RNA isolated from duplicate infected cultures ± S.D. *, p < 0.05.

β-Catenin/TCF Signaling Is Activated after Bleomycin-induced Lung Injury in Vivo

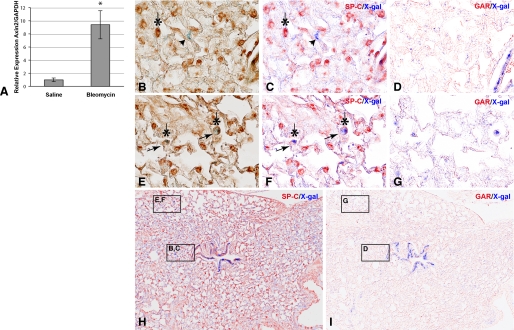

Endogenous activation of β-catenin signaling in primary AT2 cells was surprising, given that most cultured cell lines exhibit low to undetectable levels of the signaling form of β-catenin (e.g. see Fig. 5B, MDCK cells). We reasoned that the isolation and short term culturing of rat AT2 cells may represent a form of cell/tissue injury and that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling might accompany that injury, as previously indicated (45–48). To address this, we used an established mouse model of alveolar epithelial cell injury by intratracheal administration of bleomycin (33) and sought evidence for canonical Wnt pathway activation by monitoring expression levels of the immediate early target gene, AXIN2. Lungs harvested 6 days after bleomycin-instillation showed a ∼10-fold increase in AXIN2 mRNA expression by quantitative PCR compared with saline-treated control animals (Fig. 4A). Using the AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mouse, we observe that this pathway is activated in both airway and alveolar compartments after injury (Fig. 4, H and I). Specifically, we can detect SP-C-positive cells that are also X-gal-positive, suggesting that Wnt/β-catenin signaling can be up-regulated in mouse AT2 cells after bleomycin injury (Fig. 4, E–G). This bleomycin-induced activation of β-catenin signaling in AT2 cells has been independently observed using the TOP-gal reporter mouse (49). However, it is also evident that many cells that do not express SP-C are X-gal-positive (Fig. 4, B–D). Although an expanded study will be required to determine which other cell type(s) exhibit Wnt pathway activation during lung injury (e.g. fibroblasts, AT1, and immune cells), as well as their relative proportions, this finding demonstrates that the activation of β-catenin signaling observed in AT2 cultures may recapitulate aspects of in vivo lung injury models.

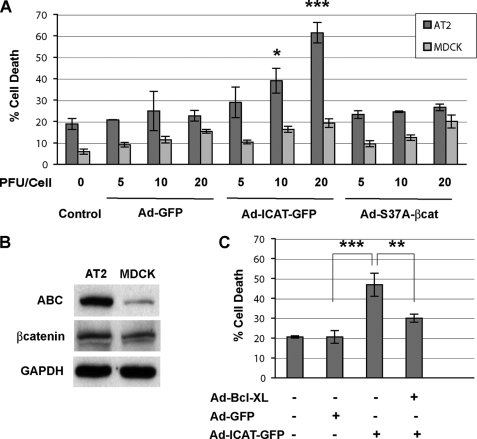

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of β-catenin/TCF-dependent transcription by ICAT promotes cell death in AT2 cells. A, cells were infected (triplicate wells) with adenoviral constructs at various plaque forming units/cell on Day0 and cultured for 3 days. Culture media was collected, cleared, and assayed for LDH as an indicator of cell death using a Roche Applied Science LDH kit. Cell death in MDCK cells, which have much less of the signaling form of β-catenin than AT2 cells (Western blot (B)), was not affected by ICAT or constitutively active S37A β-catenin. Each bar represents the mean of three independent experiments (i.e. from three different AT2 isolations and infections) ± S.D. C, ICAT-induced cell death can be partially rescued by co-infection with an adenovirus expressing the anti-apoptotic, Bcl-XL. Each bar represents the mean of three independent experiments ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001 using analysis of variance analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Bleomycin-induced lung injury activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mouse lung. A, qRT-PCR of AXIN2 mRNA expression from mouse lungs 6 days after intratracheal treatment with saline or bleomycin (0.075 unit/20-g mouse). Results are mean values from RNA isolated from three saline and three bleomycin-treated mice ± S.D. *, p < 0.05. B–I, identification of lung cell types that exhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling after bleomycin-induced injury using the AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mouse. Immunohistochemical staining of AT2 cells detected with anti-SP-C (B, C, E, F, and H) or secondary antibody controls (D and G). Bright field images in B and E were subjected to multispectral image analysis (C, D, and F–I). SP-C-positive cells (dark brown) were pseudo-colored red (*); Wnt-activated, X-gal-positive cells are blue. An SP-C-negative/X-gal-positive cell is shown in B and C (arrowhead). Two SP-C-positive/X-gal-positive cells are shown in E and F (arrows). Only ∼5% of X-gal-positive cells are double-labeled with the SP-C AT2 marker. This estimate likely under-represents the number of X-gal/SP-C “double-positive” cells observed after injury, if these cells indeed de-differentiate, lose expression of AT2 markers and give rise to AT1 cells as suggested. Saline treatment shows little X-gal staining in AXIN2+/LacZ mice (not shown).

While bleomycin-induced lung injury up-regulates β-catenin signaling over saline-treated control mice (Fig. 4A), AXIN2 message is detected in “uninjured” saline-treated lungs. This raised the possibility that there might be a low level Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a distinct population of lung cells. However, we see no clear evidence of β-catenin signaling in normal adult mouse lung using the AXIN2+/LacZ reporter mouse (50) (supplemental Fig. S3), and the active form of β-catenin (ABC) is not specifically enriched in adult rat AT2 cells (supplemental Fig. S2D). Curiously, ABC is readily detected in airway epithelial cells, but the significance of this signaling form in the absence of AXIN2+/LacZ reporter activity is unclear (supplemental Figs. S2E and S3A). Overall, these observations appear to rule out a model where AT2 progenitors are constitutively maintained by Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

β-Catenin/TCF Signaling Is Required for Alveolar Epithelial Cell Survival

Because sustained β-catenin signaling plays a causal role in cancers by activating proliferation and survival genes (51), we sought to examine the consequences of β-catenin signaling for AT2 cell survival in culture. To address this, we used adenoviral vectors to express proteins in AT2 cultures that would constitutively activate or inhibit β-catenin/TCF signaling activity. Specifically, forced activation of β-catenin signaling can be achieved by expressing a point mutant version of β-catenin that resists ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Adeno-S37A-β-catenin-HA). Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be achieved through expression of ICAT (Fig. 2A), an 81-amino acid polypeptide that specifically antagonizes β-catenin transcription through binding β-catenin and competing its interactions with both TCF and p300 (40, 52) (Adeno-myc-ICAT-GFP).

Freshly isolated AT2 cells were infected with the Adeno-GFP, Adeno-ICAT-GFP, and Adeno-S37A-β-catenin viruses, and cell death was measured by determining the percentage of LDH activity detected in the media compared with total LDH activity (media plus cell lysate) on Day4 cultures. In Fig. 5A, we show that Adeno-ICAT-GFP expression increases the release of LDH in a dose- dependent manner, whereas control Adeno-GFP and the Adeno-S37A-β-catenin viruses have little effect. Because we know that β-catenin/TCF signaling is activated by Day2 in our cultures (Figs. 1 and 2), these results demonstrate a required role for β-catenin signaling in AT2 cell culture survival. Importantly, the ability of ICAT to promote cell death critically depends on the presence of the signaling active form of β-catenin, because MDCK cells, which exhibit little constitutive β-catenin signaling (Fig. 5B), show the same low levels of death in Adeno-GFP, Adeno-ICAT-GFP, and Adeno-S37A-β-catenin infections (Fig. 5A, light gray). Of interest, the cell death induced by ICAT can be markedly reduced by co-infection with the anti-apoptotic, Bcl-XL, suggesting that β-catenin signaling may promote the survival of AT2 cultures through up-regulating the expression of components that antagonize the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Fig. 5C). The inability of Adeno-S37A-β-catenin to further enhance survival in these cultures (i.e. to reduce the baseline cell death activity to below 20%) may be due to our observation that these cultures already exhibit robust, endogenous β-catenin signaling activity (Fig. 2). Thus, additional β-catenin signaling delivered by the Adeno-S37A-β-catenin virus may not give an additive effect.

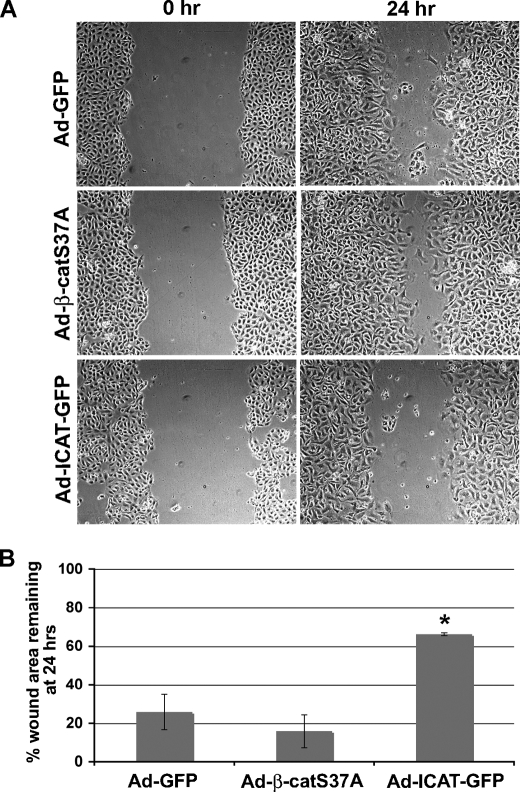

β-Catenin/TCF Signaling Is Required for AT2 Monolayer Wound Closure and the Expression of AT1 Markers

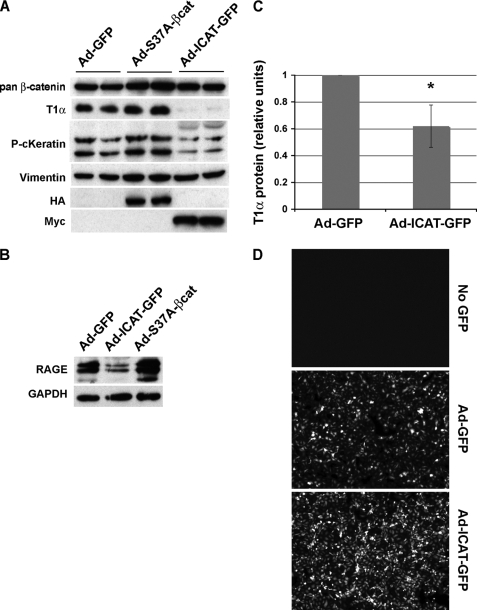

The injury-mediated up-regulation of β-catenin signaling in mouse AT2 cells (Fig. 4) raised the possibility that β-catenin signaling activation might control processes required for alveolar epithelial repair, such as migrating to close a wound and establishing an AT1 cell phenotype. Using our adenoviral expression constructs, we show that Adeno-ICAT-GFP expression significantly suppresses AT2 migration after scratch-wounding the monolayer (Fig. 6). Adeno-S37A-β-catenin consistently enhances the rate of closure compared with mock infected cells (Adeno-GFP), although this effect was not statistically significant. We also show that Adeno-ICAT-GFP expression strongly suppresses the level of AT1 markers, T1α and RAGE, compared with Adeno-GFP- or S37A-β-catenin-infected cells (Fig. 7). This effect was specific, because total β-catenin and GAPDH loading controls were unaffected by Adeno-ICAT expression. Moreover, vimentin protein levels (used to assess fibroblast contamination) were unchanged, demonstrating that the reductions in T1α and RAGE protein were not simply due to an increased proportion of fibroblasts in these cultures. As a positive control, we show that keratin 8, a recently identified β-catenin/TCF target gene (53) could be regulated by β-catenin/TCF signaling in AT2 cells (Fig. 7A). Together, these data reveal that β-catenin signaling in AT2 cultures is required for the expression of markers of type 1 cell differentiation, raising the possibility that this pathway may be required for specification of the AT1 phenotype. Consistent with this model, up-regulation of the signaling form of β-catenin (ABC) in AT2 cultures perfectly correlates with the up-regulation of T1α protein (Fig. 1B, Days 2 and 3), further suggesting that Wnt/β-catenin signaling contributes to the expression of these AT1 cell markers.

FIGURE 6.

β-catenin/TCF-signaling is required for AT2 wound repair after monolayer injury. A, AT2 cells were infected on Day0 with the respective viral constructs. On Day2, confluent monolayers were scratched and then photographed at 0- and 24-h time points. Representative images for each infection and time point are shown. B, wound surface area was quantified from the images in A at 0 and 24 h and expressed as the percentage of wound area remaining at 24 h. Bars reflect mean values from three independent experiments ± S.D. The difference between Ad-S37A-β-catenin and Ad-ICAT-GFP infections is considered statistically significant (p < 0.05) using analysis of variance analysis (*).

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of β-catenin/TCF-dependent transcription by ICAT antagonizes expression of markers of AT1 cell differentiation. AT2 cells were isolated from rat lungs and infected (in duplicate wells) with adenoviral constructs on Day0 and lysed on Day3 of culture. A, total β-catenin, T1α (AT1 marker), pan-cytokeratin (epithelial marker), vimentin (fibroblast marker), β-tubulin (loading control), and HA and Myc tags for Ad-S37A-β-catenin-HA and Ad-myc-ICAT-GFP, respectively, were detected by Western blot as described under “Materials and Methods.” Duplicate infections are shown in parallel lanes. B, Western blot for RAGE (AT1 marker) and GAPDH (loading control) from adenovirus-infected cells (Day3). Note that ICAT decreases the expression of T1α and RAGE; constitutively active β-catenin does not apparently alter AT2 transdifferentiation, despite the fact that the S37A-β-catenin adenovirus is competent to up-regulate the β-catenin/TCF target gene, AXIN2 (not shown). This experiment was carried out using nine different rat AT2 isolates on different days; six of nine experiments showed an inhibition of >2-fold. C, graph represents normalized densitometry values of scans from T1α immunoblots. Densitometry was performed using the CanoScan software (Canon) and analyzed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Error bars reflect ± S.E. The two-tailed p value is 0.0519 (*). D, live cell GFP-fluorescence images of control, Ad-GFP-infected, and Ad-ICAT-GFP-infected AT2 cells 72 h post-infection. Note that many cells expressing Ad-ICAT-GFP are viable as assessed by GFP fluorescence and the exclusion of Trypan blue (not shown).

DISCUSSION

It has long been viewed that AT2 cells may serve as progenitors for the replacement of AT1 cells after lung injury, but the signaling pathways that control this progenitor-differentiated cell relationship have remained poorly defined. Because the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is known to regulate progenitor cell-differentiated cell relationships in many adult tissues (reviewed in Ref. 14), we sought to determine whether AT2 cells are the type of progenitor that exhibits constitutive β-catenin signaling or, instead, manifest signaling upon injury. We find no evidence that AT2 cells are maintained by constitutive β-catenin signaling using the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, AXIN2+/LacZ, reporter mouse or by following the signaling form of β-catenin (ABC) in freshly isolated rat AT2 cells (Fig. 1 and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Instead, we find that β-catenin signaling is activated in AT2 cells in vivo after bleomycin-induced lung injury (Fig. 4) and in vitro after being isolated and cultured (Fig. 2). In AT2 cultures, β-catenin signaling is required for the survival, migration, and expression of two markers of type 1 cell differentiation, T1α and RAGE (Figs. 5–7). Together, these findings raise the possibility that AT2 cells behave more as facultative progenitors (54), where injury-induced activation of β-catenin signaling may effectively “reprogram” AT2 cells, allowing them to acquire AT1 characteristics and repair the alveolar epithelium. This model is compatible with previous studies showing a requirement for β-catenin in the development of distal airway and alveolar structures (25, 55), as well as recent microarray data showing up-regulation of the Wnt-receptor, Frizzled 2, in AT2 cultures and freshly isolated AT1 cells (Day0) compared with Day0 AT2 cells (56).

The robust up-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in AT2 cultures, and its apparent requirement for the expression of type 1 markers, T1α and RAGE, raises the interesting possibility that Wnt signaling is critical for the manifestation of this alveolar epithelial phenotype. Whether β-catenin/TCF controls the expression AT1 markers, T1α and RAGE, directly or indirectly is not yet clear. Whereas the 10-kb proximal promoter region of T1α contains three consensus sites for TCF binding, we found no strong evidence that β-catenin signaling could enhance transcription of a T1α-luciferase reporter (kindly provided by Maria Ramirez (57)). Evidence for a more indirect mechanism may be supported by the observation that forced activation of β-catenin signaling does not obviously enhance the expression of T1α or RAGE (Fig. 7, A and B, respectively; Adeno-S37A-β-catenin lanes). Given evidence that β-catenin can recruit factors to TCF-bound promoters that promote local chromatin remodeling (13), it is also possible that β-catenin recruitment to more distal loci may de-condense the T1α promoter region so that it becomes accessible to other factors that ultimately drive its constitutive expression in type 1 cells. Of further note, evidence that ICAT-mediated inhibition of β-catenin/TCF signaling is insufficient to up-regulate the expression of AT2 markers, SP-C and SP-D (not shown), suggests that the inhibition of AT1 markers is not simply through maintenance of the AT2 phenotype.

The mechanism by which β-catenin/TCF signaling promotes AT2 survival is likely through the activation of target genes that prevent apoptosis, because we find that the anti-apoptotic, Bcl-XL, can rescue the viability of cells treated with the β-catenin/TCF signaling inhibitor, ICAT. In this regard, survivin is an anti-apoptotic protein and direct target of β-catenin/TCF signaling in colon cancer cell lines (58, 59). Likewise, c-myc is an established β-catenin/TCF target in numerous cell types (55, 60), where it can inhibit apoptosis in certain contexts (61). Whether these β-catenin/TCF target genes are up-regulated in AT2 cells and mediate the survival of these cultures is not yet clear. Lastly, in contrast with a previous report (62), we found that only a negligible number of AT2 cells proliferate in culture (bromodeoxyuridine assay, data not shown), thus any required role for β-catenin/TCF signaling in AT2 cell proliferation will need to be evaluated in vivo.

Evidence for activation of β-catenin signaling both in primary AT2 cell cultures and during bleomycin-induced lung injury suggests that these two processes may be related. A number of recent studies have observed up-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and pathway components upon placing primary cells in culture (63, 64). Moreover, Wnts are known to bind the extracellular matrix (65), and heparin has been shown to enhance β-catenin signaling activation, presumably by preventing the sequestration of Wnts by matrix components (66, 67). We speculate that the act of isolating AT2 cells from whole lung may release Wnts from the extracellular matrix and activate signaling in primary cell culture, a model that is consistent with the observed phospho-activation of the Wnt co-receptor, LRP, in AT2 cultures (Fig. 3). These findings also raise the possibility that AT2 cell cultures may recapitulate aspects of an in vivo response to lung injury, such that activation of β-catenin signaling in AT2 cells may reprogram these cells toward an AT1 phenotype.

Altogether, this study demonstrates that β-catenin signaling plays an important role in the survival and differentiation of AT2 cell cultures, which may be relevant to the restoration of a normal epithelium after distal lung injury. In this regard, a recent study has shown that intratracheal instillation of freshly isolated AT2 cells can reduce the manifestations of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (68). Given evidence that alveolar cell death can exacerbate lung injury/ARDS fibrosis (33, 69), our findings raise the possibility that pharmacologic activators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling may promote alveolar epithelial repair after injury, a model that is under current investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Ridge and members of the Cell Culture Core (supported by a Program Project Grant awarded to J. Sznajder) for providing primary rat AT2 cells, Leland Dobbs for the SP-D antibody, Mary Williams for the T1α antibody, Nav Chandel for the Bcl-XL adenovirus, and members of the Pulmonary and Critical Care Division for advice and discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM076561 (to C. J. G.). This work was also supported by a National Research Service Award (HL78145) from NHLBI, NIH (to A. P. L.), by Grant T32 HL076139 (to S. R.), by the Northwestern Memorial Faculty Foundation (to M. J.), by Grants HL071643 and ES015024 and an NIEHS, NIH ONES Award (to G. M. M.), by Grants HL071643 and ES013995 (to G. R. S. B.), and by Career Development Awards from the Schweppe Foundation and the American Heart Association (Grant 0530304Z).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

The day of isolation and plating is designated culture Day0.

- AT1

- -2, alveolar epithelial Type 1 and 2 cells

- TCF

- T-cell factor

- ICAT

- inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF

- RAGE

- receptor for advanced glycation end products

- GSK3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- E3

- ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney cell

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- X-gal

- 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- Ad

- adenovirus

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- ABC

- active-β-catenin

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcription.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daniels C. B., Orgeig S. (2003) News Physiol. Sci. 18, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George C. L., Goss K. L., Meyerholz D. K., Lamb F. S., Snyder J. M. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wofford J. A., Wright J. R. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 293, L1437–L1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weibel E. R. (1986) Bull. Eur. Physiopathol. Respir. 22, 235s–239s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brody J. S., Williams M. C. (1992) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 54, 351–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borok Z., Li C., Liebler J., Aghamohammadi N., Londhe V. A., Minoo P. (2006) Pediatr. Res. 59, 84R–93R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aso Y., Yoneda K., Kikkawa Y. (1976) Lab. Invest. 35, 558–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamson I. Y., Bowden D. H. (1974) Lab. Invest. 30, 35–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isakson B. E., Lubman R. L., Seedorf G. J., Boitano S. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. 281, C1291–C1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbs L. G., Williams M. C., Brandt A. E. (1985) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 846, 155–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borok Z., Danto S. I., Lubman R. L., Cao Y., Williams M. C., Crandall E. D. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, L155–L164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borok Z., Lubman R. L., Danto S. I., Zhang X. L., Zabski S. M., King L. S., Lee D. M., Agre P., Crandall E. D. (1998) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 18, 554–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willert K., Jones K. A. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 1394–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C., Li Y., Semenov M., Han C., Baeg G. H., Tan Y., Zhang Z., Lin X., He X. (2002) Cell 108, 837–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart M., Concordet J. P., Lassot I., Albert I., del los Santos R., Durand H., Perret C., Rubinfeld B., Margottin F., Benarous R., Polakis P. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peifer M., Sweeton D., Casey M., Wieschaus E. (1994) Development 120, 369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staal F. J., Noort Mv M., Strous G. J., Clevers H. C. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3, 63–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korinek V., Barker N., Moerer P., van Donselaar E., Huls G., Peters P. J., Clevers H. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato N., Meijer L., Skaltsounis L., Greengard P., Brivanlou A. H. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reya T., Duncan A. W., Ailles L., Domen J., Scherer D. C., Willert K., Hintz L., Nusse R., Weissman I. L. (2003) Nature 423, 409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Es J. H., Jay P., Gregorieff A., van Gijn M. E., Jonkheer S., Hatzis P., Thiele A., van den Born M., Begthel H., Brabletz T., Taketo M. M., Clevers H. (2005) Nature Cell Biol. 7, 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benhamouche S., Decaens T., Godard C., Chambrey R., Rickman D. S., Moinard C., Vasseur-Cognet M., Kuo C. J., Kahn A., Perret C., Colnot S. (2006) Dev. Cell 10, 759–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekine S., Lan B. Y., Bedolli M., Feng S., Hebrok M. (2006) Hepatology 43, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clevers H. (2006) Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mucenski M. L., Wert S. E., Nation J. M., Loudy D. E., Huelsken J., Birchmeier W., Morrisey E. E., Whitsett J. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40231–40238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mucenski M. L., Nation J. M., Thitoff A. R., Besnard V., Xu Y., Wert S. E., Harada N., Taketo M. M., Stahlman M. T., Whitsett J. A. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 289, L971–L979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds S. D., Zemke A. C., Giangreco A., Brockway B. L., Teisanu R. M., Drake J. A., Mariani T., Di P. Y., Taketo M. M., Stripp B. R. (2008) Stem Cells 26, 1337–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zemke A. C., Teisanu R. M., Giangreco A., Drake J. A., Brockway B. L., Reynolds S. D., Stripp B. R. (2009) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobbs L. G., Gonzalez R., Williams M. C. (1986) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 134, 141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridge K. M., Rutschman D. H., Factor P., Katz A. I., Bertorello A. M., Sznajder J. L. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 273, L246–L255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J., Chen Z., Narasaraju T., Jin N., Liu L. (2004) Lab. Invest. 84, 727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeBiase P. J., Lane K., Budinger S., Ridge K., Wilson M., Jones J. C. (2006) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 54, 665–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budinger G. R., Mutlu G. M., Eisenbart J., Fuller A. C., Bellmeyer A. A., Baker C. M., Wilson M., Ridge K., Barrett T. A., Lee V. Y., Chandel N. S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4604–4609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masckauchán T. N., Shawber C. J., Funahashi Y., Li C. M., Kitajewski J. (2005) Angiogenesis 8, 43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Loos C. M. (2008) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 56, 313–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H. M., Jerchow B., Sheu T. J., Liu B., Costantini F., Puzas J. E., Birchmeier W., Hsu W. (2005) Development 132, 1995–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirasawa M., Fujiwara N., Hirabayashi S., Ohno H., Iida J., Makita K., Hata Y. (2004) Genes Cells 9, 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams M. C. (2003) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 669–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Noort M., Meeldijk J., van der Zee R., Destree O., Clevers H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17901–17905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tago K., Nakamura T., Nishita M., Hyodo J., Nagai S., Murata Y., Adachi S., Ohwada S., Morishita Y., Shibuya H., Akiyama T. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1741–1749 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jho E. H., Zhang T., Domon C., Joo C. K., Freund J. N., Costantini F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1172–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maher M. T., Flozak A. S., Stocker A. M., Chenn A., Gottardi C. J. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 186, 219–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonnerot C., Rocancourt D., Briand P., Grimber G., Nicolas J. F. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6795–6799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng X., Tamai K., Doble B., Li S., Huang H., Habas R., Okamura H., Woodgett J., He X. (2005) Nature 438, 873–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chilosi M., Poletti V., Zamò A., Lestani M., Montagna L., Piccoli P., Pedron S., Bertaso M., Scarpa A., Murer B., Cancellieri A., Maestro R., Semenzato G., Doglioni C. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 1495–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okuse T., Chiba T., Katsuumi I., Imai K. (2005) Wound Repair Regen. 13, 491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dell'accio F., De Bari C., Eltawil N. M., Vanhummelen P., Pitzalis C. (2008) Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1410–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dell'Accio F., De Bari C., El Tawil N. M., Barone F., Mitsiadis T. A., O'Dowd J., Pitzalis C. (2006) Arthritis Res. Ther. 8, R139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konigshoff M., Kramer M., Balsara N., Wilhelm J., Amarie O. V., Jahn A., Rose F., Fink L., Seeger W., Schaefer L., Gunther A., Eickelberg O. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 772–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu B., Yu H. M., Hsu W. (2007) Dev. Biol. 301, 298–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polakis P. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1837–1851 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daniels D. L., Weis W. I. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 573–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yochum G. S., McWeeney S., Rajaraman V., Cleland R., Peters S., Goodman R. H. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3324–3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stripp B. R., Reynolds S. D. (2008) Proc. Am. Thoracic Soc. 5, 328–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shu W., Guttentag S., Wang Z., Andl T., Ballard P., Lu M. M., Piccolo S., Birchmeier W., Whitsett J. A., Millar S. E., Morrisey E. E. (2005) Dev. Biol. 283, 226–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez R., Yang Y. H., Griffin C., Allen L., Tigue Z., Dobbs L. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 288, L179–L189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez M. I., Rishi A. K., Cao Y. X., Williams M. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26285–26294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang F., Phiel C. J., Spece L., Gurvich N., Klein P. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33067–33077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim P. J., Plescia J., Clevers H., Fearon E. R., Altieri D. C. (2003) Lancet 362, 205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He T. C., Sparks A. B., Rago C., Hermeking H., Zawel L., da Costa L. T., Morin P. J., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (1998) Science 281, 1509–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson E. B. (1998) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60, 575–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhaskaran M., Kolliputi N., Wang Y., Gou D., Chintagari N. R., Liu L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3968–3976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng J. H., She H., Han Y. P., Wang J., Xiong S., Asahina K., Tsukamoto H. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294, G39–G49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodwin A. M., Sullivan K. M., D'Amore P. A. (2006) Dev. Dyn. 235, 3110–3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Papkoff J., Schryver B. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2723–2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reichsman F., Smith L., Cumberledge S. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135, 819–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsieh J. C., Rattner A., Smallwood P. M., Nathans J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3546–3551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Serrano-Mollar A., Nacher M., Gay-Jordi G., Closa D., Xaubet A., Bulbena O. (2007) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 1261–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sheppard D. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1501–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maher M. T., Flozak A. S., Hartsell A. M., Russell S., Beri R., Peled O. N., Gottardi C. J. (2009) Biol. Direct 4, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.