Abstract

Runx2 is a key transcription factor regulating osteoblast differentiation and skeletal morphogenesis, and FGF2 is one of the most important regulators of skeletal development. The importance of the ERK mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway in cranial suture development was demonstrated by the findings that the inhibition of FGF/FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling by a MEK blocker prevents the premature suture closure caused by an Fgfr2 mutation in mice. We previously demonstrated that ERK activation does not affect Runx2 gene expression but that it stimulates Runx2 transcriptional activity. However, the molecular mechanism underlying Runx2 activation by FGF/FGFR or ERK was still unclear. In this study, we found that FGF2 treatment increased the protein level of exogenously overexpressed Runx2 and that this increase is reversed by ERK inhibitors. In contrast, overexpression of constitutively active MEK strongly increased the Runx2 protein level, which paralleled an increase in Runx2 acetylation. As Runx2 protein phosphorylation mediated by ERK directly correlates with Runx2 protein stabilization, acetylation, and ubiquitination, we undertook to identify the ERK-dependent phosphorylation sites in Runx2. Analysis of two C-terminal Runx2 deletion constructs showed that the middle third of the protein is responsible for ERK-induced stabilization and activation. An in silico analysis of highly conserved ERK targets indicated that there are three relevant serine residues in this domain. Site-directed mutagenesis implicated Ser-301 in for ERK-mediated Runx2 stabilization and acetylation. In conclusion, the FGF2-induced ERK MAP kinase strongly increased the Runx2 protein level through an increase in acetylation and a decrease in ubiquitination, and these processes require the phosphorylation of Runx2 Ser-301 residue.

Keywords: ERK, Protein Degradation, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Stability, Ubiquitination, FGF2, Runx2, Acetylation

Introduction

RUNX2, a member of the RUNX family of transcription factors, encodes a nuclear protein with a runt DNA binding domain (1, 2). As a key transcription factor of osteoblast differentiation and skeletal morphogenesis, it regulates the expression of various bone marker genes, including osteocalcin, type I collagen, osteopontin, and alkaline phosphatase (3, 4). Human molecular genetic studies (5–7) and mouse mutagenesis experiments (8, 9) clearly showed that RUNX2 mutations are associated with cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by hypoplastic clavicles, patent sutures, and fontanelles, supernumerary teeth, short stature, and a variety of skeletal anomalies (10). In addition, Runx2-deficient mice completely lack mineralized bones (8, 9, 11), indicating that the protein is a master transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation and bone mineralization.

Our previous studies showed that Runx2 gene expression is regulated by osteogenic signals such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs),2 transforming growth factors (TGF) (12–15), and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) (16). Among these osteogenic signals, FGF2 has been reported to play important roles in skeletal development and growth (17–19). Disruption of the murine Fgf2 gene results in decreased bone mass and bone formation (20). In contrast, Fgf2-overexpressing transgenic mice show premature mineralization and achondroplasia (21). FGF ligand binding to cognate receptors (FGFRs) leads to their phosphorylation and subsequent activation, resulting in downstream signal transduction through the protein kinase C (PKC), phospholipase C, and MAP kinase pathways (22, 23). We previously showed that PKC-δ activation by FGF2 is important not only for Runx2 expression but also for Runx2 transcriptional activation (16), whereas the ERK and p38 MAP kinases are involved in the latter but not former process. Recently, Shukla et al. (24) demonstrated that blocking MEK/ERK signaling by RNA interference that targets a constitutive-active mutation of Fgfr2 (Fgfr2S252W) or with the MEK inhibitor U0126 could prevent the craniosynostosis phenotype caused by a constitutively active Fgfr2 mutation in knock-in mice. Moreover, the CCD bone phenotype caused by Runx2 haploinsufficiency is rescued by osteoblast-specific expression of constitutively active MEK in a mouse model, whereas the CCD phenotype is exacerbated with a dominant-negative version of MEK (25).

As a critical determinant for osteoblast differentiation, the transcriptional activity of Runx2 can be controlled post-translationally by various extracellular signals (16, 25–32). Previous studies showed that phosphorylation of serine 247 of Runx2 is responsible for its transcriptional activation by FGF2-stimulated PKC-δ (33) and by BMP2-stimulated p300-mediated Runx2 acetylation, which inhibits the Smurf1-mediated degradation of Runx2 (34). These results led us to think that there might be a control relationship between the phosphorylation and acetylation of Runx2 by FGF2-stimulated ERK MAP kinase that increases its stability and transactivation potential. In this study, we demonstrate relationships between the FGF/FGFR-activated ERK MAP kinase and post-translational modifications of Runx2 and its activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Recombinant human FGF2 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). DMEM, α-MEM, fetal bovine serum, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from HyClone Labs (Logan, UT). The Bio-Rad protein assay and the luciferase assay system were from Bio-Rad and Promega (Madison, WI), respectively. The MEK inhibitor U0126, the p38 inhibitor SB203580, and the JNK inhibitor JNKII were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-acetyl-lysine, anti-Myc, and anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Covance Research Products (Berkeley, CA), and Sigma, respectively. Anti-Runx2 antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Goat-anti-mouse IgG-HRP was obtained from Pierce. Complete protease inhibitor mixture tablets and phosphatase inhibitor mixture 1/2 were purchased from Roche (Mannheim, Germany) and Sigma, respectively. MG132 and cycloheximide (CHX) were from Sigma. Sodium butyrate was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY).

DNA Constructs and Site-directed Mutagenesis

The Runx2 full-length type I construct (MRIPV N-terminal sequence) and the p6xOSE2-Luc reporter plasmid were previously described (16). pRL-TK vector was purchased from Promega. To generate the Runx2 S282A, S301A, and S319A mutants, the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, and amino acid changes were confirmed by sequencing. The primers used are as follows: forward 5′-CTT GTG GAT TAA AAG GAG CTG GTG CAG AGT TCA GG-3′ and reverse 5′-CCT GAA CTC TGC ACC AGC TCC TTT TAA TCC ACA AG-3′ for S282A; forward 5′-CAG GCA GGC ACA GTC TGC ACC ACC GTG GTC CTA TG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAT AGG ACC ACG GTG GTG CAG ACT GTG CCT GCC TG-3′ for S301A; forward 5′-CTG AGC CAG ATG ACA GCC CCA TCC ATC CAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTG GAT GGA TGG GGC TGT CAT CTG GCT CAG-3′ for S319A. The constitutively active (CA) MEK1 plasmid and pEGFP-N1 vector were purchased from Stratagene and Clontech (Palo Alto, CA), respectively. The Flag-ubiquitin expression vector was previously described (35).

Cell Culture

C2C12 cells and 293T cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in 5% CO2. MC3T3-E1 cells were maintained in α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Following transient transfection, the 293T cells were further cultured in serum-free DMEM for 16 h. After stimulation with FGF2 (10 ng/ml) in serum-free medium for an additional 8 h, cells were harvested and subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis. For the kinase inhibitor experiment, the cells were pretreated for 1 h with U0126 (10 μm), SB203580 (25 μm), or JNKII (50 μm), and then treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2.

Transient Transfection

Cells were transfected using HilyMax transfection reagent (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) or Attractene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. 293T cells were cultured in 60-mm dishes for 16 h, the medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and the cells were transfected with the DNA construct or with empty vector. The cells were then transferred to fresh growth medium for 24 h.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in HEPES lysis buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm sodium butyrate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 10% glycerol) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors mixture 1/2. Total cell lysates containing 1 mg of protein were immunoprecipitated with the primary antibody and protein G-agarose beads. The agarose beads were washed, and bead-bound proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE. Gel proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, the blots were probed with antibodies and detected using a SUPEX Western blot detection kit (DyneBio, Seongnamsi, Korea).

Luciferase Assay

C2C12 cells were cultured in 96-well assay plates and transfected with 100 ng/well reporter vector and/or 200 ng/well expression vector plus 10 ng/well Renilla luciferase vector in serum-free medium. After 6 h of transfection, cells were cultured overnight in fresh medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, which was then replaced with serum-free medium with or without 10 ng/ml FGF2, and incubation was continued for 8 h. Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase assay kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer's protocols. The lysates were analyzed with the GloMax-multi Detection System (Promega).

Half-life of Runx2

293T cells were co-transfected with Myc-Runx2 with or without (CA) MEK expression vector. Transfected cells were treated with 50 μg/ml CHX and harvested. The level of Runx2 was analyzed by immunoblotting using the anti-Myc antibody.

Ubiquitination of Runx2

293T cells were co-transfected with Myc-Runx2 (wild type or mutants) and Flag-ubiquitin. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 and 10 ng/ml FGF2 for 8 h. Myc-Runx2 was immunoprecipitated using the anti-Myc antibody and protein G-agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates were loaded onto an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride, and probed with the anti-Flag antibody.

RESULTS

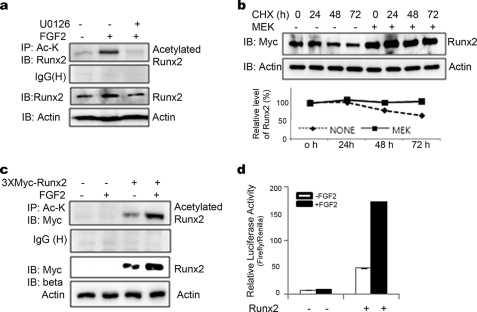

FGF2 Increases Runx2 Protein Stability and Acetylation Levels via the ERK MAP Kinase

FGF2 is known to activate the Runx2 transcription factor in osteoblasts (31). Phosphorylation and acetylation of Runx2 are the main mechanisms of increasing its transcriptional activity (34), but their relationship in Runx2 regulation has not been clearly defined. We first determined whether Runx2 protein and acetylation levels are regulated by FGF2. First of all, we measured the change of total and acetylated endogenous Runx2 protein level by FGF2 treatment in MC3T3-E1. FGF2 treatment increased total and acetylated Runx2 protein level, and an ERK-specific inhibitor, U0126, dramatically blocked FGF2-induced increase of Runx2 (Fig. 1a). To estimate the Runx2 stability by MEK, The 293T cell were transfected Runx2 with or without CA-MEK. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time and harvested. CA-MEK clearly extends the half-life of the Runx2 protein and enhances the accumulation of Runx2 (Fig. 1b). Immunoblot analysis showed that both total and acetylated Runx2 levels were increased by FGF2 treatment (Fig. 1c). Runx2 transcriptional activity in C2C12 cells was increased by overexpression of Runx2 or by FGF2 treatment alone. FGF2 treatment synergistically up-regulated Runx2 transcriptional activity in C2C12 cells transiently overexpressing Runx2 (Fig. 1d). As the MAP kinase pathway is the major downstream signaling pathway for FGF/FGFR and Runx2 is also known to be activated by this pathway, we examined which MAP kinases are responsible for FGF2-dependent increases in total and acetylated Runx2 protein levels. For this purpose, we treated cells with kinase-specific inhibitors 1 h before FGF2 treatment. U0126, SB203580, and JNKII are selective inhibitors for the ERK, p38, and JNK MAP kinases, respectively. The ERK-specific inhibitor U0126 completely blocked FGF2-dependent increases in total and acetylated Runx2 protein levels and Runx2 transcriptional activity, but blocking p38 or JNK had no effect in this respect (Fig. 2, a and b). These results strongly show that FGF2 up-regulates Runx2 protein and acetylation levels via the ERK MAP kinase pathway.

FIGURE 1.

FGF2 increases the Runx2 protein and acetylation levels and transcription activity and MEK enhances Runx2 stability. a, MC3T3-E1 cells were pretreated for 1 h with 10 μm U0126 and then treated or not for 8 h with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Acetylated endogenous Runx2 was detected by immunoprecipitation with an anti-acetyl-lysine antibody followed by immunoblotting with an anti-Runx2 antibody. The endogenous Runx2 protein level was estimated by immunoblotting with the anti-Runx2 antibody. b, 293T cells were transfected with the 3xMyc-Runx2 and CA-MEK or empty vector. The transfected cells treated with 50 μl/ml cycloheximide were harvested. Total Runx2 level was estimated by immunoblotting with an anti-Myc antibody. c, 293T cells were transfected with the pCDNA3.1–3xMyc-Runx2 expression vector. 24 h post-transfection, cells were serum-starved for 16 h and then treated for 8 h with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Acetylated Runx2 was detected by immunoprecipitation with an anti-acetyl-lysine antibody followed by immunoblotting with an anti-Myc antibody. The Runx2 protein level was estimated by immunoblotting with the anti-Myc antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. d, C2C12 cells were transiently co-transfected with the 3xMyc-RUNX2 and pGL3–6XOSE-Luc vectors plus pRL-TK vectors. After 24 h, the cells were serum-starved for 16 h and then treated for 8 h with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Runx2 transcriptional activity was estimated by a luciferase assay and normalized to Renilla luciferase.

FIGURE 2.

The ERK MAP kinase pathway is required for FGF2-enhanced Runx2 stability and transcriptional activity. a, 293T cells were transfected with the pCDNA3.1–3xMyc-Runx2 expression vector. 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved for 16 h, pretreated for 1 h with 10 μm U0126, 25 μm, SB203580, or 50 μm JNKII, and then treated or not for 8 h with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Acetylated Runx2 and total Runx2 were detected as in Fig. 1. b, C2C12 cells were transiently co-transfected with the 3xMyc-Runx2 and pGL3–6XOSE-Luc vectors plus pRL-TK vectors. After 24 h, the cells were serum-starved for 16 h, pretreated or not for 1 h with the indicated inhibitor, and then treated or not for 8 h with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Runx2 transcriptional activity was estimated with the luciferase assay.

The PST Domain (Amino Acids 259–397) Is Responsible for FGF2-dependent Increases in Runx2 Stability and Transcriptional Activity

The increases in FGF2-dependent Runx2 acetylation and protein were blocked by an ERK-specific inhibitor (Fig. 2), and ERK activation can selectively rescue impaired bone phenotypes caused by Runx2 haploinsufficiency (25), strongly suggesting that the ERK MAP kinase is a crucially important signaling molecule for regulating the post-translational modification of Runx2 and its transcriptional activity. Therefore, we questioned whether phosphorylation of Runx2 by the ERK MAP kinase affects its acetylation and stability. To identify Runx2 sites phosphorylated by the FGF2-stimulated ERK MAP kinase, we made two Runx2 deletion constructs; the first, ΔPST1, is composed of amino acids 1–258 (259–558 are deleted), and the second, ΔPST2, contains amino acids 1–397 (398–558 are deleted) (Fig. 3a). The Runx2 ΔPST1 construct exhibited a complete absence of the FGF2-induced increase in the Runx2 protein level and activity, whereas the Runx2 ΔPST2 construct retained FGF2 responsiveness (Fig. 3, b–d). These results indicate that the PST domain of Runx2 (amino acids 259–397) plays a crucial role in FGF2-stimulated acetylation and stability and that this region contains putative ERK phosphorylation sites that are stimulated by FGF2.

FIGURE 3.

The region between amino acids 259 and 397 of Runx2 is responsible for stability and transcriptional activity stimulated by FGF2. a, diagrammatic representation of Runx2 constructs. RHD, runt homology domain; PST, proline/serine/threonine rich domain; NMTS, nuclear matrix targeting signal. b, 293T cells were transfected with wild-type Runx2, ΔPST1 Runx2, or ΔPST2 Runx2 expression vectors. FGF2 was treated as in Fig. 1. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc and anti-β-actin antibodies. Runx2 proteins are marked with asterisks, and β-actin is marked with arrows. c, total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-acetyl-lysine antibody followed by immunoblotting using the anti-Myc antibody. Acetylated Runx2 is marked with asterisks. d, C2C12 cells were co-transfected with the Runx2 expression vector and reporter vector plus pRL-TK vectors. After 24 h, cells were serum-starved for 16 h and then treated with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for 8 h.

Ser-301 Phosphorylation of Runx2 by the ERK Kinase Plays a Crucial Role in FGF2-increased Runx2 Stability and Transcriptional Function

To identify specific phosphorylation sites in Runx2 recognized by FGF2-stimulated ERK, we analyzed the region between amino acids 259 and 397 using PhosphoScansite 2.0, a proteome-wide program that predicts cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs (36). Potential sites were Ser-282, Ser-301, and Ser-319 (Fig. 4a). To test these candidates, we performed site-directed mutagenesis to substitute serine residues with alanine to induce constitutive dephosphorylation of the residue. These mutations were confirmed by sequencing (Fig. 4b). The Runx2-S282A and Runx2-S319A mutants still showed increased Runx2 acetylation levels and transcription activity after FGF2 treatment, like wild-type Runx2. Interestingly, the Runx2-S301A mutant almost completely lacked FGF2-stimulated acetylation and transcription activity (Fig. 4, c and d). To confirm the effect of the ERK kinase on Runx2 acetylation and stability, as well as to confirm the functional site, we used constitutively active MEK (CA-MEK) instead of FGF2. CA-MEK can also stimulate Runx2 acetylation and stability and transcriptional activity. As shown in Fig. 4, c and d, the Runx2-S301A mutant did not show MEK responsiveness (Fig. 4, e and f). Our data indicate that Ser-301 of Runx2 is a critical ERK phosphorylation site responsible for FGF2-stimulated Runx2 acetylation and stability.

FIGURE 4.

Ser-301 in Runx2 is the major FGF2-induced ERK-dependent phosphorylation site. a, structure of Runx2 with candidate phosphorylation sites. b, 293T cells were transfected with wild-type Runx2, 282A Runx2, 301A Runx2, or 319A Runx2 expression vectors. After 24 h, cells were serum-starved for 16 h and then treated or not with 10 ng/ml FGF2 for 8 h. Acetylated Runx2 and total Runx2 were detected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. c, C2C12 cells were co-transfected with wild-type Runx2 or a Runx2 mutant (282A, 301A, or 319A) and reporter vector plus pRL-TK vectors. After 24 h, the cells were serum-starved for 16 h and treated with FGF2 for 8 h. Runx2 transcriptional activity was estimated with the luciferase assay. d, 293T cells were co-transfected with CA-MEK and Runx2 constructs. After 24 h, cells were harvested, and total cell lysates were analyzed as in Fig. 4c. e, C2C12 cells were co-transfected with wild-type Runx2 or a Runx2 mutant (282A, 301A, or 319A) and a reporter vector with (solid bars) or without (blank bars) CA-MEK plus pRL-TK vectors. 24 h post-transfection, luciferase activities were determined.

FGF2 Inhibits the Ubiquitination of Runx2 in an ERK-dependent Manner, Resulting in an Increase of Runx2 Stability

It has been reported that Runx2 is degraded through a Smurf-mediated ubiquitination pathway (37). Specifically, a previous study showed that BMP2 signaling stimulates p300-mediated Runx2 acetylation, increasing transactivation function, and inhibiting Smurf1-mediated degradation of Runx2 (34). To determine whether the phosphorylation of Runx2 by the FGF2-stimulated ERK MAP kinase can similarly protect it from degradation by ubiquitination, resulting in an increase in Runx2 stability and transactivation function, we performed an in vivo ubiquitination assay. Although wild-type Runx2 and Runx2-S301A ubiquitination was detected in this assay, Runx2-S301A was modified to a greater extent. In addition, ubiquitination of wild-type Runx2 was decreased by FGF2, but Runx2-S301A was not changed in this respect (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the FGF2 enhances Runx2 protein stability by decreasing ubiquitination and that Ser-301 phosphorylation of Runx2 by activated ERK protects it from ubiquitination-mediated degradation.

FIGURE 5.

FGF2 inhibits Runx2 polyubiquitination. a, 293T cells were co-transfected with Flag-ubiquitin and Myc-Runx2 (wild type or the S301A mutant). 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with MG132 and FGF2 for 8 h. b, 293T cells were co-transfected with Flag-ubiquitin and Myc-Runx2 (wild type or the S301A) with or without CA-MEK. 24 h after transfection, cells was treated with MG132 for 8 h. Ubiquitination of RUNX2 was analyzed by immunoprecipitation of 1 mg of lysates with the anti-Myc antibody followed by immunoblotting with an anti-Flag antibody.

DISCUSSION

The importance of RUNX2 in osteogenesis has been clearly demonstrated by mouse models and human genetic studies (5, 8, 11). RUNX2 is an indispensable transcription factor for bone development (3, 38). It is also known that many osteogenic ligands promote osteogenesis not only by stimulating Runx2 expression but also by promoting Runx2 transcriptional activity. Many kinases are involved in ligand-dependent Runx2 regulation. For example, parathyroid hormone inhibits RUNX2 through protein kinase A (39). BMP2 or TGF-β1 stimulates Runx2 through Smad phosphorylation and the p38 or ERK MAP kinases (40–42). FGF signaling stimulates Runx2 gene expression through PKC-δ (16) and enhances Runx2 activity through the PKC, ERK, and p38 MAP kinase pathways (16). Although it was indicated that these kinases phosphorylate Runx2 Ser/Thr residues, little information was available concerning which residue is phosphorylated and how phosphorylation stimulates protein activity (33, 43). Among these kinases, the ERK MAP kinase is commonly activated by BMP2, TGF-β1, and FGF2 treatment in osteoblasts (31, 44).

Acetylation by the FGF2-stimulated ERK MAP Kinase Stabilizes and Activates the Runx2 Protein

We previously showed that FGF2 treatment increases the endogenous Runx2 protein level (16). However, it was not clear whether this increase came from an increase in de novo Runx2 expression or from the prolonged presence of previously synthesized Runx2. Our additional prior results also indicated that Runx2 protein acetylation by BMP2 strongly increases its stability (34). In this study, we found that FGF2 strongly increased Runx2 acetylation as well as stability. Moreover, treatment of Runx2-overexpressing cells with FGF2 conferred a strong synergistic increase in Runx2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1), indicating the importance of acetylation for Runx2 stability and transcriptional activity.

Our next result showed that the FGF2-induced increase of Runx2 acetylation and transcriptional activation clearly correlated with activation by the ERK MAP kinase. Several studies have shown that ERK activation stimulates Runx2 activity and osteoblast differentiation (26, 31, 45–47). Taken together, the FGF2-increased stabilization, acetylation, and activation of Runx2 are clearly caused by ERK and not by other MAP kinases.

Phosphorylation of Ser-301 Is Critical for Runx2 Acetylation

The ERK MAP kinase is principally involved in the phosphorylation of Ser/Thr protein residues. To determine which domain of Runx2 is responsible for its acetylation by FGF2 treatment, we analyzed two C-terminal deletion constructs, which showed that a critical residue might be in the amino acid 259–397 region. The basal level of the total and acetylated ΔPST1 Runx2 seems to be increased compared with wild-type Runx2. We previously reported that lysine residues in the central and C-terminal regions of Runx2 increases the susceptibility of protein to degradation, and that acetylation of the lysine residues protects Runx2 from degradation using Runx2-KR-225/230/350/351 mutant (37). Because of the ΔPST1 Runx2 removed most of Runx2 acetylation by p300, the basal level of ΔPST1 Runx2 was increased compared with wild type. However, this is not relevant, because we focused on which site in the Runx2 is responsible for the ERK signal. It has been reported that the PST region of RUNX2 is required for FGF2-induced transcription activity (31). However, this study did not explain how Runx2 phosphorylation regulates its transcriptional activity nor did it identify the ERK phosphorylation site. Several groups have studied Runx2 phosphorylation residues and their functions. Wee et al. (43) showed that Ser-104 and Ser-451 are phosphorylated and are implicated in negatively regulating RUNX2 function. We also previously showed that the Runx2 Ser-247 residue is phosphorylated by direct PKC-δ activation (33).

An ERK-specific phosphorylation site has been reported for AML1. The Ser-249 and Ser-266 residues of AML1 are major and minor ERK-dependent phosphorylation sites, respectively, and ERK phosphorylation potentiates the transactivation ability of AML1 (48). Interestingly, the ERK phosphorylation residues in AML1 are also conserved in human RUNX2 and mouse Runx2. There are three highly conserved ERK MAP kinase target sites, Ser-282, Ser-301, and Ser-319, and each residue is found in mouse and rat Runx2 proteins as well. Based on a recent report of Ge et al., Ser-301 and Ser-319 are the phosphorylation target sites of ERK-MAP kinase (49). In this report, our site-directed mutagenesis studies of these serine residues showed that acetylation of Runx2 protein is dependent on Ser-301 phosphorylation. Therefore, even though both Ser-301 and Ser-319 are important targets of Runx2 phosphorylation by ERK-MAP kinase, phosphorylation of Ser-301 only is able to trigger subsequent Runx2 acetylation and stabilization. Ge et al. showed Ser-319 phosphorylation directly by mass spectroscopic (MS) analysis. Meanwhile, they could not provide direct evidence of Ser-301 phosphorylation by MS analysis but provided indirect evidence such as metabolic radiolabeling and gel mobility shift data. They assumed that the difficulties in identification of Ser-301 phosphorylation in MS analysis might result from some changes in secondary structure by subsequent post-translational modification (49). This assumption is quite well matched with our present evidence that phosphorylation of Ser-301-mediated acetylation or other modifications may influence the Runx2 secondary structure and make Ser-301 phosphorylation hardly detectable. These results indicate that the proximal PST domain, and especially Ser-301, is critical for FGF2-induced Runx2 phosphorylation, acetylation, and stabilization. Matsuzaki et al. (50) reported that acetylation and phosphorylation cooperatively regulate the function of Foxo1, because acetylated Foxo1 becomes more sensitive to PKB-dependent phosphorylation. This finding supports the possibility that phosphorylation-dependent regulation of Runx2 is relevant to acetylation and that Runx2 acetylation regulates its transcriptional activity.

Phosphorylation of Ser-301 Is Critical for the ERK-induced Runx2 Stabilization against Ubiquitin-dependent Degradation

In this study, we found that FGF2 decreases Runx2 ubiquitination and that Runx2-S301A did not show this phenotype after FGF2 treatment. These data suggest that Runx2 phosphorylation controls ubiquitination in an ERK-dependent manner. Sears et al. (51) reported that activation of the Ras/Raf/ERK pathway extends the half-life of the Myc protein and enhances the accumulation of Myc activity, and that phosphorylation of Ser-62 is required for the Ras-induced stabilization of Myc (52). Phosphorylation of Ser-456 plays a role in the regulation of Checkpoint kinase 2 stability after DNA damage (53), and PKC-mediated Ser-193 phosphorylation regulates c-FLIP ubiquitination and stability (54). These results suggest that the phosphorylation of specific serine residues can control target protein stability by ubiquitination.

We have focused on ERK-dependent Runx2 phosphorylation and post-translational modification. However, many bone-derived growth and signaling factors can regulate Runx2 as activation cofactors. Histone deacetylase-6 interacts with RUNX2 and represses Runx2-dependent transcription (55). We previously reported that BMP2 signaling stimulates p300-mediated Runx2 acetylation, increasing its transactivation activity and inhibiting Smurf-1-mediated degradation (34). TGF-β can stimulate p300-dependent RUNX3 acetylation through inhibiting ubiquitination-mediated degradation (56). Therefore, it remains to be clarified whether the ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Runx2 involves cofactors. In conclusion, we have shown that the FGF2-stimulated ERK activation and subsequent phosphorylation of Ser-301 in the Runx2 protein is clearly related to an increased acetylation level, which subsequently stabilizes Runx2 by inhibiting ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

This work was supported by the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare (A010252 and A085021), and by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund, KRF-2008-532-C00018).

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factors

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAP

- mitogen-activated protein

- FGFR

- FGF receptor

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levanon D., Negreanu V., Bernstein Y., Bar-Am I., Avivi L., Groner Y. (1994) Genomics 23, 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogawa E., Maruyama M., Kagoshima H., Inuzuka M., Lu J., Satake M., Shigesada K., Ito Y. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6859–6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducy P., Zhang R., Geoffroy V., Ridall A. L., Karsenty G. (1997) Cell 89, 747–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein G. S., Lian J. B., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., Montecino M., Javed A., Zaidi S. K., Young D. W., Choi J. Y., Pockwinse S. M. (2004) Oncogene 23, 4315–4329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mundlos S., Otto F., Mundlos C., Mulliken J. B., Aylsworth A. S., Albright S., Lindhout D., Cole W. G., Henn W., Knoll J. H., Owen M. J., Mertelsmann R., Zabel B. U., Olsen B. R. (1997) Cell 89, 773–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee B., Thirunavukkarasu K., Zhou L., Pastore L., Baldini A., Hecht J., Geoffroy V., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (1997) Nat. Genet. 16, 307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H. J., Nam S. H., Park H. S., Ryoo H. M., Kim S. Y., Cho T. J., Kim S. G., Bae S. C., Kim I. S., Stein J. L., van Wijnen A. J., Stein G. S., Lian J. B., Choi J. Y. (2006) J. Cell Physiol. 207, 114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto F., Thornell A. P., Crompton T., Denzel A., Gilmour K. C., Rosewell I. R., Stamp G. W., Beddington R. S., Mundlos S., Olsen B. R., Selby P. B., Owen M. J. (1997) Cell 89, 765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi J. Y., Pratap J., Javed A., Zaidi S. K., Xing L., Balint E., Dalamangas S., Boyce B., van Wijnen A. J., Lian J. B., Stein J. L., Jones S. N., Stein G. S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8650–8655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mundlos S. (1999) J. Med. Genet. 36, 177–182 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komori T., Yagi H., Nomura S., Yamaguchi A., Sasaki K., Deguchi K., Shimizu Y., Bronson R. T., Gao Y. H., Inada M., Sato M., Okamoto R., Kitamura Y., Yoshiki S., Kishimoto T. (1997) Cell 89, 755–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M. H., Javed A., Kim H. J., Shin H. I., Gutierrez S., Choi J. Y., Rosen V., Stein J. L., van Wijnen A. J., Stein G. S., Lian J. B., Ryoo H. M. (1999) J. Cell Biochem. 73, 114–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee K. S., Kim H. J., Li Q. L., Chi X. Z., Ueta C., Komori T., Wozney J. M., Kim E. G., Choi J. Y., Ryoo H. M., Bae S. C. (2000) Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 8783–8792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M. H., Kim Y. J., Kim H. J., Park H. D., Kang A. R., Kyung H. M., Sung J. H., Wozney J. M., Ryoo H. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34387–34394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee M. H., Kim Y. J., Yoon W. J., Kim J. I., Kim B. G., Hwang Y. S., Wozney J. M., Chi X. Z., Bae S. C., Choi K. Y., Cho J. Y., Choi J. Y., Ryoo H. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35579–35587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H. J., Kim J. H., Bae S. C., Choi J. Y., Ryoo H. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canalis E., Centrella M., McCarthy T. (1988) J. Clin. Invest. 81, 1572–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayahara H., Ito T., Nagai H., Miyajima H., Tsukuda R., Taketomi S., Mizoguchi J., Kato K. (1993) Growth Factors 9, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang H., Pun S., Wronski T. J. (1999) Endocrinology 140, 5780–5788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero A., Okada Y., Tomita M., Ito M., Tsurukami H., Nakamura T., Doetschman T., Coffin J. D., Hurley M. M. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1085–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coffin J. D., Florkiewicz R. Z., Neumann J., Mort-Hopkins T., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Lightfoot P., German R., Howles P. N., Kier A., O'Toole B. A. (1995) Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1861–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlessinger J., Plotnikov A. N., Ibrahimi O. A., Eliseenkova A. V., Yeh B. K., Yayon A., Linhardt R. J., Mohammadi M. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nugent M. A., Iozzo R. V. (2000) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 32, 115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla V., Coumoul X., Wang R. H., Kim H. S., Deng C. X. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39, 1145–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge C., Xiao G., Jiang D., Franceschi R. T. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176, 709–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanno T., Takahashi T., Tsujisawa T., Ariyoshi W., Nishihara T. (2007) J. Cell Biochem. 101, 1266–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuoka H., Shibata S., Suda N., Yamashita Y., Komori T. (2007) J. Anat. 211, 8–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassan M. Q., Tare R. S., Lee S. H., Mandeville M., Morasso M. I., Javed A., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., Stein G. S., Lian J. B. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40515–40526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi K. Y., Kim H. J., Lee M. H., Kwon T. G., Nah H. D., Furuichi T., Komori T., Nam S. H., Kim Y. J., Ryoo H. M. (2005) Dev. Dyn. 233, 115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang S., Wei D., Wang D., Phimphilai M., Krebsbach P. H., Franceschi R. T. (2003) J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 705–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao G., Jiang D., Gopalakrishnan R., Franceschi R. T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36181–36187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naganawa T., Xiao L., Coffin J. D., Doetschman T., Sabbieti M. G., Agas D., Hurley M. M. (2008) J. Cell Biochem. 103, 1975–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim B. G., Kim H. J., Park H. J., Kim Y. J., Yoon W. J., Lee S. J., Ryoo H. M., Cho J. Y. (2006) Proteomics 6, 1166–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon E. J., Lee K. Y., Choi N. S., Lee M. H., Kim H. N., Jin Y. H., Ryoo H. M., Choi J. Y., Yoshida M., Nishino N., Oh B. C., Lee K. S., Lee Y. H., Bae S. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16502–16511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon W. J., Cho Y. D., Cho K. H., Woo K. M., Baek J. H., Cho J. Y., Kim G. S., Ryoo H. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32751–32761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obenauer J. C., Cantley L. C., Yaffe M. B. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3635–3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao M., Qiao M., Oyajobi B. O., Mundy G. R., Chen D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27939–27944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H. J., Park H. D., Kim J. H., Cho J. Y., Choi J. Y., Kim J. K., Shin H. I., Ryoo H. M. (2004) J. Cell Biochem. 91, 1239–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li T. F., Dong Y., Ionescu A. M., Rosier R. N., Zuscik M. J., Schwarz E. M., O'Keefe R. J., Drissi H. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 299, 128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryoo H. M., Lee M. H., Kim Y. J. (2006) Gene 366, 51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bae S. C., Lee Y. H. (2006) Gene 366, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee K. S., Hong S. H., Bae S. C. (2002) Oncogene 21, 7156–7163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wee H. J., Huang G., Shigesada K., Ito Y. (2002) EMBO Rep. 3, 967–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao G., Gopalakrishnan R., Jiang D., Reith E., Benson M. D., Franceschi R. T. (2002) J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai C. F., Chaudhary L., Fausto A., Halstead L. R., Ory D. S., Avioli L. V., Cheng S. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14443–14450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaiswal R. K., Jaiswal N., Bruder S. P., Mbalaviele G., Marshak D. R., Pittenger M. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9645–9652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franceschi R. T., Xiao G., Jiang D., Gopalakrishnan R., Yang S., Reith E. (2003) Connect Tissue Res. 44, Suppl. 1, 109–116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka T., Kurokawa M., Ueki K., Tanaka K., Imai Y., Mitani K., Okazaki K., Sagata N., Yazaki Y., Shibata Y., Kadowaki T., Hirai H. (1996) Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 3967–3979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ge C., Xiao G., Jiang D., Yang Q., Hatch N. E., Roca H., Franceschi R. T. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32533–32543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuzaki H., Daitoku H., Hatta M., Aoyama H., Yoshimochi K., Fukamizu A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11278–11283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sears R., Leone G., DeGregori J., Nevins J. R. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sears R., Nuckolls F., Haura E., Taya Y., Tamai K., Nevins J. R. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2501–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kass E. M., Ahn J., Tanaka T., Freed-Pastor W. A., Keezer S., Prives C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30311–30321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaunisto A., Kochin V., Asaoka T., Mikhailov A., Poukkula M., Meinander A., Eriksson J. E. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 1215–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westendorf J. J., Zaidi S. K., Cascino J. E., Kahler R., van Wijnen A. J., Lian J. B., Yoshida M., Stein G. S., Li X. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7982–7992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin Y. H., Jeon E. J., Li Q. L., Lee Y. H., Choi J. K., Kim W. J., Lee K. Y., Bae S. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29409–29417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]