Abstract

Rhesus monkey TRIM5α (TRIM5αrh) includes RING, B-box, coiled-coil, and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains and blocks HIV-1 infection by targeting HIV-1 core through a B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain. Previously, we reported that TRIM5αrh also blocks HIV-1 production in a B30.2(PRYSPRY)-independent manner. Efficient encapsidation of TRIM5αrh, but not human TRIM5α (TRIM5αhu), in HIV-1 virus-like particles suggests the interaction between Gag and TRIM5αrh during viral assembly. Here, we determined responsible regions for late restriction activity of TRIM5αrh. The RING disruption, but not the replacement with human TRIM21 RING, ablated the efficient encapsidation and the late restriction, suggesting that a RING structure was essential for the late restriction and efficient interaction with HIV-1 Gag. The prominent cytoplasmic body formation of TRIM5αrh, which depended on the coiled-coil domain and the ensuing linker 2 region, was not required for the encapsidation. Intriguingly, TRIM5αrh coiled-coil domain mutants (M133T and/or T146A) showed impaired late restriction activity, despite the efficient encapsidation and cytoplasmic body formation. Our results suggest that the TRIM5αrh-mediated late restriction involves at least two distinct activities as follows: (i) interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyprotein through the N-terminal, RING, and B-box 2 regions of a TRIM5αrh monomer, and (ii) an effector function(s) that depends upon the coiled-coil and linker 2 domains of TRIM5αrh. We speculate that the TRIM5αrh coiled-coil region recruits additional factor(s), such as other TRIM family proteins or a cellular protease, during the late restriction. RBCC domains of TRIM family proteins may play a role in sensing newly synthesized viral proteins as a part of innate immunity against viral infection.

Keywords: Viruses/Antiviral Agents, Viruses/HIV, Viruses/Lentivirus, Viruses/Replication, Innate Immunity, Restriction, TRIM5α

Introduction

TRIM5α is a member of the tripartite motif (TRIM)2 family of proteins and contains RING, B-box 2, and coiled-coil domains (1). Similar to other cytoplasmic TRIM proteins, TRIM5α contains a C-terminal B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain that is thought to mediate binding to specific ligands (1). Rhesus monkey TRIM5α (TRIM5αrh) blocks an early step of HIV-1 infection, prior to significant reverse transcription (2, 3), by recognizing the incoming HIV-1 core structure with the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain and promoting its degradation or premature disassembly (4, 5). Sequences in the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain dictate the potency and specificity of the restriction of particular retroviruses (4, 6–8). Disruption of the B-box 2 domain of TRIM5αrh eliminates the ability of the protein to block HIV-1 infection, thus indicating its importance (6, 9). A recent study suggests that the B-box 2 mediates higher order self-association of TRIM5αrh oligomers to potentiate the restriction of retroviral infection (10). The coiled-coil domain of TRIM5α contributes to protein oligomerization and efficient capsid binding and post-entry restriction (10, 11). Disruption of the TRIM5αrh RING domain decreases, but does not eliminate, the restriction of HIV-1 infection (8, 12). Although polyubiquitination and rapid degradation of TRIM5α depend upon intact RING and B-box 2 domains (13), rapid turnover of TRIM5α is not required for its post-entry restriction activity, and proteasome inhibitors cannot prevent the post-entry restriction (9, 14). These observations suggest the block of HIV-1 entry occurs independently of the ubiquitin/proteasome system. More recent studies, however, have demonstrated that proteasome inhibitors can relieve the TRIM5α-dependent inhibition of reverse transcription without impairing the block of HIV-1 nuclear entry (2, 15). Moreover, TRIM5α is rapidly degraded in cells exposed to a restriction-sensitive retrovirus, suggesting a role of proteasomal degradation in the restriction (5). Similar to other TRIM proteins, TRIM5α self-associates to form cytoplasmic bodies (11, 16), which turn over rapidly by exchanging with free cytoplasmic TRIM5α as well as neighboring TRIM5α bodies (17).

In addition to this well characterized post-entry restriction activity, TRIM5αrh has another “late restriction” activity to affect the production phase of the HIV-1 life cycle (12, 18, 19). Richardson et al. (19) have demonstrated that cell-associated HIV-1 transmission in human cells is blocked only when both donor and recipient cells express TRIM5αrh. We and others (18, 20) have shown that co-expression of the C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged TRIM5αrh with HIV-1 proviral plasmids reduces the yield of infectious virus up to 20–100-fold, although the late restriction activity of endogenous TRIM5αrh remains controversial (18, 20). High levels of TRIM5αrh showed potent antiviral activity on HIV-1 production through degradation of Gag polyproteins, whereas modest TRIM5αrh expression blocks HIV-1 production by reducing the virion infectivity as well as the yield of infectious virus (12, 16). When HIV-1 production surpasses the late restriction activity, HIV-1 virions or virus-like particles (VLPs) produced in the presence of TRIM5αrh protein incorporate high levels of intact and truncated forms of TRIM5αrh (12, 16). Efficient encapsidation of TRIM5αrh is also evident in HIV-1 Gag-only particles (12), suggesting that TRIM5αrh interacts with HIV-1 Gag polyproteins before or during Gag assembly and that Gag maturation is not necessary for the Gag-TRIM5αrh interaction during the late restriction. HIV-1 protease appears to cleave TRIM5αrh to produce the truncated 20-kDa form of TRIM5αrh in the VLPs, because HIV-1 protease inhibitors block the formation of the 20-kDa form in the VLPs (12). However, this truncation of TRIM5αrh is not necessary for the late restriction, because TRIM5αrh RBCC-TRIM5αhu B30.2(PRYSPRY) chimeras exhibit efficient VLP incorporation and potent late restriction activities without showing remarkable truncation (12).

When compared with TRIM5αrh, human TRIM5α (TRIM5αhu) shows marginal antiviral activity on HIV-1 production (12, 16, 18). Little or no encapsidation of TRIM5αhu protein in HIV-1 virions or HIV-1 VLPs (12, 16) implies weaker interaction of HIV-1 Gag polyproteins with TRIM5αhu than TRIM5αrh. A series of TRIM5αrh-TRIM5αhu chimeric constructs reveal that the RBCC (RING, B-box 2, and coiled-coil) domain, but not the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain, of TRIM5αrh determines both the late restriction activity as well as the encapsidation efficiency (12). A series of C-terminally HA-tagged TRIM5αrh mutants with deletions in the N- or C-terminal regions indicate the following: (i) the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain is dispensable for the late restriction activity and efficient encapsidation of TRIM5αrh; (ii) the coiled-coil domain is essential for the late restriction but not for the efficient encapsidation, and (iii) the N-terminal region is essential for efficient TRIM5α encapsidation (16).

In this study, we further characterized the domains responsible for the TRIM5α-mediated late restriction using TRIM5αrh-TRIM5αhu chimeras and deletion/point mutants. We found that a RING structure and the TRIM5αrh B-box 2, coiled-coil, and ensuing linker 2 domains are required for the late restriction activity, efficient VLP encapsidation, and prominent cytoplasmic body formation. Intriguingly, TRIM5αrh coiled-coil point mutants with M133T and/or T146A were efficiently incorporated into VLPs but did not strongly block HIV-1 production. Our data suggest that the TRIM5αrh-mediated block of HIV-1 production involves at least two distinct activities, including interaction with HIV-1 Gag through the N-terminal region, RING and B-box 2 regions of TRIM5αrh, and an effector function(s) that depends upon the coiled-coil and linker 2 region of TRIM5αrh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

293T and GHOST(3)R3/X4/R5 (21) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics.

Plasmids

C-terminally HA-tagged TRIM5αhu- and TRIM5αrh-expressing plasmids, pHuT5α and pRhT5α, were described previously (12). The N-terminal deletion mutant D0 has the first 14 amino acids replaced with a single amino acid Met, whereas the C-terminal deletion mutants SP1 and CC1 have the deletions in the B30.2(PRYSPRY) region and the B30. 2(PRYSPRY) and coiled-coil region, respectively (16). All the RBCC chimeric constructs as well as point mutants were generated by extension PCR. pLPCX-based TRIM5αrh RING motif mutants, TRIM5 + 21R and C15A/C18A, as well as their parental pLPCX-TRIM5αrh were kindly provided by Dr. Sodroski (4, 22). Codon-optimized HIV-1 Gag-Pol- and Gag-expression plasmids, pH-GP and pH-Gag, were described previously (12). Infectious molecular clone pNL4-3 (23) was used to produce HIV-1.

p24 Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay and Titration

293T cells (106 cells/well in a 6-well plate) were transfected with 1.0 μg of a TRIM5α expression plasmid together with 0.2 μg of pNL4-3 by 6 μl of FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total DNA concentrations were adjusted to 1.2 μg with pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen). Forty eight hours post-transfection, supernatants were harvested and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. Viral titers in the supernatants were determined in GHOST(3)R3/X4/R5 indicator cells. The concentrations of p24 in the supernatants were assayed with the p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (ZeptoMetrix). For immunoblotting analysis of TRIM5α and HIV-1 Gag proteins, the transfected cells were lysed with RIPA buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE with a 4–15% gradient gel (Bio-Rad) and immunoblotting analysis. Following transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, TRIM5α protein was detected by rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody, 3F10 (Roche Applied Science), whereas mouse anti-p24 monoclonal antibodies, AG3.0 (24) and 183-H12–5C (25), were used to detect HIV-1 precursor Gag and p24 capsid proteins. For treatment with proteasome inhibitors, 293T cells, which were transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid and pNL4-3, were treated with various concentrations of proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (Sigma) or MG115 (Sigma), for 16 h before cells were harvested for immunoblotting.

Encapsidation Assay

293T cells (106 cells/well in a 6-well plate) were transfected with 0.3 μg of pH-GP together with 0.9 μg of a TRIM5α-expressing plasmid with 6 μl of FuGENE 6. The amounts of plasmid DNA were adjusted to 1.2 μg with pcDNA3.1(+) for each transfection. Forty eight hours post-transfection, culture supernatants were harvested and passed through a 0.45-μm pore-sized filter. VLPs in 1 ml of supernatants were purified by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. The pellets of VLPs were washed by phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed in 10 μl of RIPA buffer. Proteins were separated by 4–15% gradient gel SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis with rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody (3F10, Roche Applied Science) or anti-p24 monoclonal antibody mixtures (AG3.0 and 183-H12-5C). Use of gradient gels was critical to visualize both the intact and truncated forms of TRIM5αrh.

Immunofluorescent Analysis

293T cells were transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid as described above. Sixteen hours post-transfection, cells were resuspended, seeded in 8-well Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International), and cultured for 20 h. Cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.05% saponin at 4 °C for 30 min. HA-tagged TRIM5α mutants were detected with a rat anti-HA antibody 3F10 and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody. Nuclei were counter-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Subcellular localization of TRIM5α proteins was determined under a confocal microscope.

RESULTS

RING Domain Is Required to Block HIV-1 Production

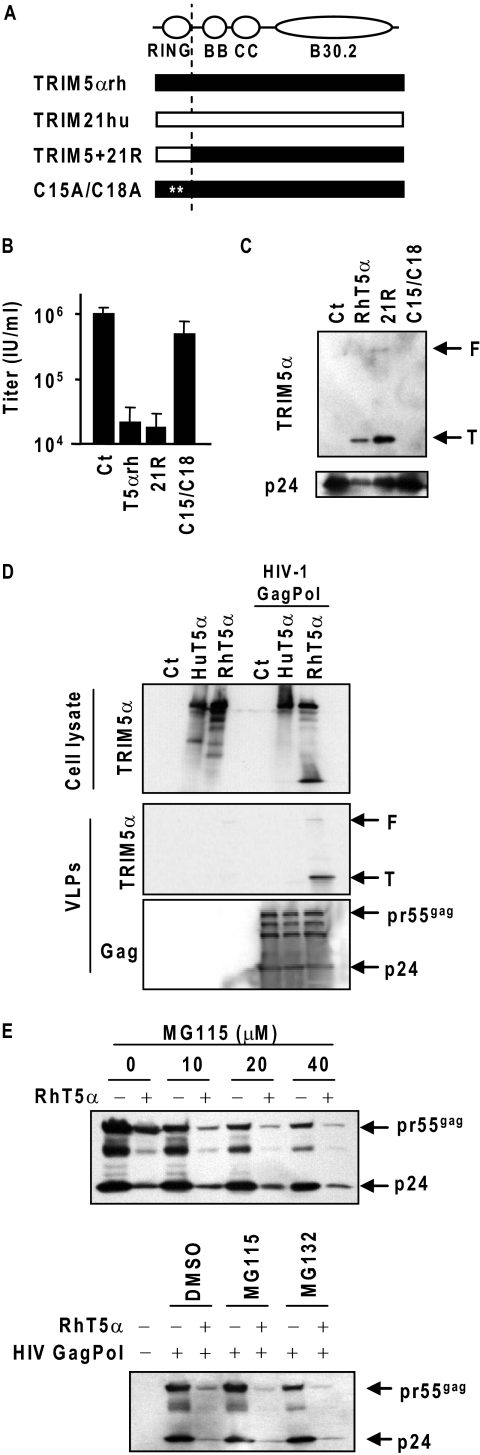

Previously, we have shown that the deletion in the first 14 amino acid residues prior to the RING consensus sequence abrogates the efficient VLP encapsidation as well as the strong late restriction activity of TRIM5αrh (16). Similarly, N-terminally FLAG-tagged TRIM5αrh did not show strong late restriction activity (12). These observations suggest that the N-terminal region of TRIM5αrh is required for interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyprotein or for proper TRIM5α conformation. To further understand the domains necessary for the late restriction, we first tested the influence of mutations in the TRIM5αrh RING domain on the late restriction activity. Two RING domain mutants, TRIM5-21R and C15A/C18A, were used to assess the importance of the RING motif in TRIM5αrh (Fig. 1). TRIM5-21R is a TRIM5αrh with the RING domain replaced with the human TRIM21 RING domain (13, 26, 27), whereas C15A/C18A is a TRIM5αrh with a disrupted RING structure (27). To examine the influence of these RING mutations on HIV-1 production, 293T cells were transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid and an HIV-1 infectious molecular clone pNL4-3. As a control, we used the parental construct, pLPCX-TRIM5αrh, which expresses an HA-tagged wild-type TRIM5αrh. The viral titers in the supernatants were then determined in GHOST indicator cells. The TRIM5-21R showed late restriction activity comparable with the wild-type TRIM5αrh, whereas C15A/C18A showed impaired late restriction (Fig. 1B). This observation indicates that a RING domain is required for the late restriction. Because TRIM5-21R exhibits a longer half-life than TRIM5αrh (27), it is conceivable that rapid degradation of TRIM5αrh is not required for the late restriction.

FIGURE 1.

RING domain is required to block HIV-1 production. A, schematic representation of TRIM5α RING-mutants. Black and white bars indicate the sequences from TRIM5αrh and human TRIM21, respectively. White asterisks show the position of point mutations. B, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5αrh mutant expression plasmid along with pNL4-3. Forty eight hours post-transfection, HIV-1 titer in the supernatant was assayed in GHOST(3)R3/X4/R5 indicator cells. IU/ml, infectious unit per ml of supernatant. C, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5αrh mutant expression plasmid along with codon-optimized Gag-Pol expression plasmid. Forty eight hours post-transfection, VLPs in the supernatant were purified through a 20% sucrose layer and subjected to Western blot analysis. F and T indicate full-length and truncated forms (∼20 kDa) of TRIM5α protein. D, 293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged TRIM5αrh- or TRIM5αhu-expressing plasmids with a codon-optimized HIV-1 Gag-Pol-expressing plasmid. Forty eight hours post-transfection, cell lysates and VLPs in the supernatants were purified and analyzed with anti-HA or anti-HIV-1 p24 antibodies. F and T indicate full-length and truncated forms of TRIM5α protein. E, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5αrh mutant expression plasmid along with pNL4-3 and treated with increasing concentrations of MG115. The HIV-1 Gag proteins in the proteasome inhibitor-treated cells were detected by Western blot analysis (upper panel). We also tested the effect of another proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (lower panel).

Next, we examined whether these RING mutants can interact with the Gag protein by encapsidation into VLPs made with a codon-optimized HIV-1 Gag-Pol. 293T cells were co-transfected with TRIM5α- and codon-optimized Gag-Pol-expressing plasmids. VLPs purified through a 20% sucrose layer were analyzed for TRIM5α incorporation (Fig. 1C). A truncated form of TRIM5α (∼20 kDa) was readily detected in the VLPs made in the presence of wild-type TRIM5αrh and TRIM5-21R but not C15A/C18A. When TRIM5αrh was expressed without HIV-1 Gag-Pol proteins, no TRIM5αrh protein could be detected in the pellets (Fig. 1D). Although full-length and truncated (20 kDa) forms of TRIM5α protein were observed in cell lysates, the 20-kDa form was predominant in the VLPs, ruling out the possible precipitation of TRIM5αrh-containing cell debris without VLP encapsidation. These data indicate that a RING domain is required for the efficient interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyproteins.

The block of HIV-1 entry appears to occur independently of the ubiquitin/proteasome system during the TRIM5αrh-mediated post-entry restriction (9, 14), although more recent studies have demonstrated that proteasome inhibitors can partially relieve the TRIM5α-dependent inhibition of reverse transcription without affecting the restriction of HIV-1 nuclear entry (2, 15). We examined the influence of proteasome inhibitors on the late restriction. 293T cells were co-transfected with pRhT5α and pNL4-3. One day after transfection, the supernatants were replaced with fresh growth medium containing a proteasome inhibitor, MG132 or MG115. After an overnight treatment, culture supernatants and producer cells were harvested. Because of the potent toxicity of MG132 and MG115, we did not determine the viral titers. To assess the effects of proteasome inhibitors, the HIV-1 Gag proteins in the producer cells were detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 1E). Although we observed the toxicity associated with higher concentrations of proteasome inhibitor treatment, MG132 or MG115 treatment did not affect the TRIM5αrh-mediated block of HIV-1 Gag production. Our results therefore suggest that the late restriction occurs independently of the ubiquitin/proteasome system.

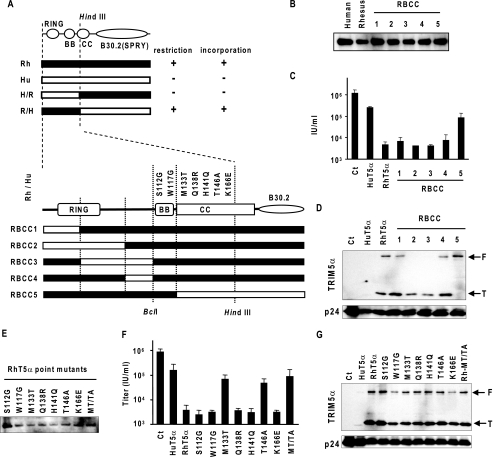

TRIM5αrh Coiled-coil Domain Is Required for the Late Restriction Activity

Our previous studies using TRIM5αhu-TRIM5αrh chimeras have shown that the TRIM5αrh RBCC domain contains the determinant for the late restriction (12, 16). To further map the responsible element(s) in TRIM5αrh-mediated restriction on HIV-1 production, we generated five additional TRIM5α RBCC chimeras, RBCC1 to RBCC5, by extension PCR. After verification of the expression of these chimeras (Fig. 2B), we examined the antiviral activity of each chimeric TRIM5α protein as described above. RBCC1 to RBCC4 showed strong antiviral activity comparable with the wild type, whereas the chimera RBCC5, which has the RING and B-box 2 domains of TRIM5αrh and coiled-coil and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains of TRIM5αhu, exhibited impaired antiviral activities (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that the coiled-coil domain of TRIM5αrh is required for the late restriction. We then examined whether these chimeras could interact with HIV-1 Gag protein by encapsidation assay. We found all chimeras were incorporated into VLPs (Fig. 2D), although RBCC2 and RBCC3 showed reduced levels of incorporation. These results suggested that the five chimeric TRIM5αs can interact with the Gag protein, and the linker region between the RING and B-box 2 domains, or the conformation of this region, affects the interaction. RBCC5 showed reduced antiviral activity yet maintained the incorporation capacity of the protein, indicating that the interaction of TRIM5α with HIV-1 Gag alone is insufficient for the late restriction activity. In addition, TRIM5α RBCC5 was incorporated into VLPs as an intact, full-length form but not in a truncated form, which confirmed our previous observation that HIV-1 protease efficiently cleaves TRIM5αrh in the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain but not TRIM5αhu (12).

FIGURE 2.

Met-133 and Thr-146 in the CC domain of TRIM5αrh are critical for the late restriction. A, summary of previous results with TRIM5αhu-TRIM5αrh chimeras (32) and schematic representation of chimeras used in this study. Black and white bars indicate sequences of rhesus (Rh) and human (Hu) TRIM5α proteins, respectively. The numbers with amino acid substitutions are based on TRIM5αrh amino acid sequence. B, 293T cells were transfected with human, rhesus, or mutant TRIM5α expression plasmid. Two days post-transfection, lysates of transfected cells were subjected to Western blot analysis, and TRIM5α proteins were detected by anti-HA monoclonal antibody. C, 293T cells were co-transfected with pNL4-3 together with a chimeric TRIM5α expression plasmid. Two days post-transfection, viral titer in the supernatant was analyzed in GHOST indicator cells. D, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid along with pH-GP. Two days post-transfection, VLPs were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis. F and T indicate full-length and truncated forms (∼20 kDa) of TRIM5α protein, respectively. E, 293T cells were transfected with human, rhesus, or mutant TRIM5α expression plasmids. Two days post-transfection, lysates of transfected cells were subjected to Western blot analysis, and TRIM5α proteins were detected by anti-HA monoclonal antibody. F, 293T cells were co-transfected with pNL4-3 along with a TRIM5α point mutant expression plasmid. Two days post-transfection, viral titer in the supernatant was analyzed in GHOST indicator cells. G, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid along with pNL4-3. Two days post-transfection, VLPs were collected and were subjected to Western blot analysis. F and T indicate full-length and truncated forms (∼20 kDa) of TRIM5α protein.

Met-133 and Thr-146 in the Coiled-coil Domain of TRIM5αrh Are Critical for the Efficient Late Restriction

There are seven amino acid differences between human and rhesus monkey TRIM5α in the BclI-HindIII region, which contains the B-box 2 and partial coiled-coil domains. To determine the amino acid residues responsible for the late restriction and encapsidation, we replaced each of these seven amino acids with a corresponding TRIM5αhu amino acid residue (Fig. 2A). After confirming the expression of these TRIM5αrh mutants (Fig. 2E), we examined their antiviral activities against HIV-1. Five TRIM5αrh mutants showed antiviral activities comparable with the wild type, although two TRIM5αrh coiled-coil domain mutants, M133T and T146A, showed impaired late restriction activity (Fig. 2F). We also generated a coiled-coil mutant, TRIM5αrh-MT/TA, with the two critical amino acid substitutions M133T and T146A. The antiviral activity of this mutant was comparable with the antiviral activities of M133T and T146A (Fig. 2F). We then examined the encapsidation efficiencies of these mutants. When HIV-1 VLPs were made in the presence of TRIM5αrh mutants, all point mutants, including the TRIM5αrh-MT/TA, were efficiently incorporated into VLPs (Fig. 2G). These data indicate that the amino acid residues Met-133 and Thr-146 are essential for the late restriction activity and further confirmed that incorporation of TRIM5α protein does not necessary lead to the late restriction. It is likely that the TRIM5αrh coiled-coil domain is required for the step(s) after the interaction of TRIM5α with HIV-1 Gag to block HIV-1 production.

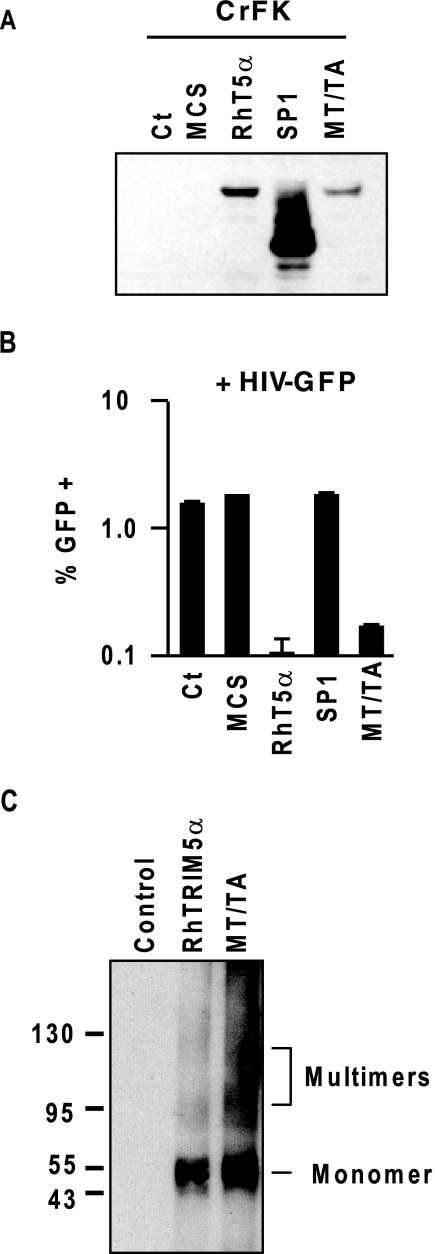

To better understand the TRIM5αrh mutant with M133T and T146A (MT/TA), we examined whether the mutant shows post-entry restriction against HIV-1 infection. Feline CrFK cells, which are highly permissive to HIV-1 vector infection, were transduced by retroviral vectors that encode HA-tagged wild-type and mutant TRIM5α proteins, MT/TA and SP1 (B30.2(PRYSPRY)-deleted). CrFK cells stably expressing the TRIM5αrh proteins were selected under the presence of G418 (1 mg/ml). Empty retroviral vector-transduced cells were used as a control. TRIM5αrh expression was verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). When the cells were infected by a green fluorescent protein-carrying HIV-1 vector at a multiplicity of infection of 0.05, MT/TA- and wild-type TRIM5αrh-expressing cells showed notable resistance to HIV-1 vector infection (Fig. 3B), suggesting the intact post-entry restriction activity of TRIM5αrh-MT/TA mutant. We also tested the potential of multimerization of the MT/TA mutant by using glutaraldehyde as cross-linker. 293T cells expressing the coiled-coil mutant were lysed in 1% Nonidet P-40 phosphate-buffered saline solution, cross-linked with 2.0 mm glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 5 min, and subsequently quenched by adding 20 mm glycine. Cross-linked substrates were then subjected to immunoblotting analysis with anti-HA antibody. The MT/TA mutant demonstrated typical multimerized signals, comparable with wild-type TRIM5αrh (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the M133T or T146A mutations in TRIM5αrh coiled-coil domain do not affect the TRIM5αrh multimerization.

FIGURE 3.

Post-entry restriction by the TRIM5αrh mutant with M133T and T146A. A, feline CrFK cells were retrovirally transduced to express TRIM5αrh mutants, MT/TA and SP1. HA-tagged TRIM5α proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody. An empty vector, multiple cloning site (MCS), was used as a control. B, G418-selected bulk populations of CrFK cells were infected by a green fluorescent protein-expressing HIV-1 vector. Green fluorescent protein-positive cell populations were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter. C, cell lysates from HA-tagged TRIM5αrh- and TRIM5αrh-MT/TA-expressing cells were cross-linked by glutaraldehyde and analyzed for multimerization by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody.

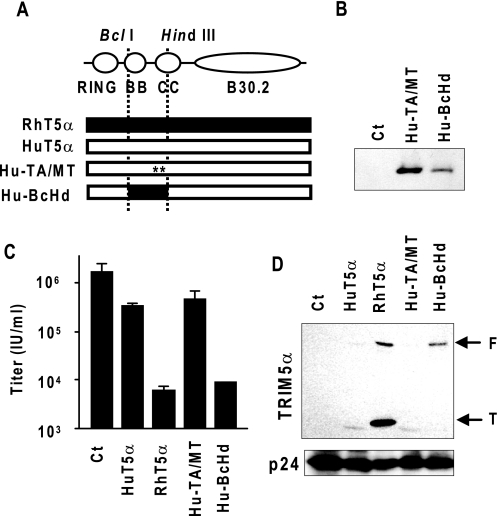

TRIM5αhu Mutant with the B-box 2 and Coiled-coil Domain of TRIM5αrh Restricts HIV-1 Production

In an attempt to make a TRIM5αhu with the late restriction activity, we replaced the essential amino acid residues/region for the late restriction with corresponding TRIM5αrh sequences. We introduced Met-133 and Thr-146 into the TRIM5αhu sequence to make TRIM5αhu-TA/MT. We also generated TRIM5αhu-BcHd by replacing the BclI-HindIII region with the corresponding TRIM5αrh region (Fig. 4A). After verifying the expression of the TRIM5αhu mutants by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B), we examined the antiviral activities of these mutants. TRIM5αhu-TA/MT did not strongly restrict HIV-1 production, whereas TRIM5αhu-BcHd restricted HIV-1 production by up to 100-fold, comparable with the antiviral activity of wild-type TRIM5αrh (Fig. 4C). We also examined the ability of these TRIM5αhu mutants to interact with HIV-1 Gag by the encapsidation assay. As shown in Fig. 4D, TRIM5αhu-BcHd, but not TRIM5αhu-TA/MT, was efficiently incorporated in the VLPs. These data further confirm that the TRIM5αrh B-box 2 and coiled-coil regions are critical for the late restriction and the efficient encapsidation of TRIM5α. Introduction of the Met-133 and Thr-146 into TRIM5αhu did not affect the antiviral activity or encapsidation efficiency of TRIM5αhu. It is plausible that the weak antiviral activity of TRIM5αhu-TA/MT on HIV-1 production is primarily due to its insufficient interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyproteins.

FIGURE 4.

TRIM5αhu chimera with the BB-CC domain of TRIM5αrh restricts HIV-1 production. A, schematic representation of TRIM5αhu mutants. Black and white bars indicate the sequence from rhesus (rh) and human (hu) TRIM5α proteins, respectively. Asterisks indicate the position of substitutions. B, 293T cells were transfected with TRIM5αhu mutant expression plasmids. Two days post-transfection, lysates of transfected cells were subjected to Western blot analysis, and the mutants were detected by anti-HA monoclonal antibody. C, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5αhu mutant expression plasmid along with pNL4-3. Two days post-transfection, viral titer in the supernatant was analyzed in GHOST indicator cells. D, 293T cells were co-transfected with a TRIM5α mutant expression plasmid along with pH-GP. Two days post-transfection, VLPs were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis to detect incorporated TRIM5α-protein by anti-HA monoclonal antibody. F and T indicate full-length and truncated form (∼20 kDa) of TRIM5α proteins.

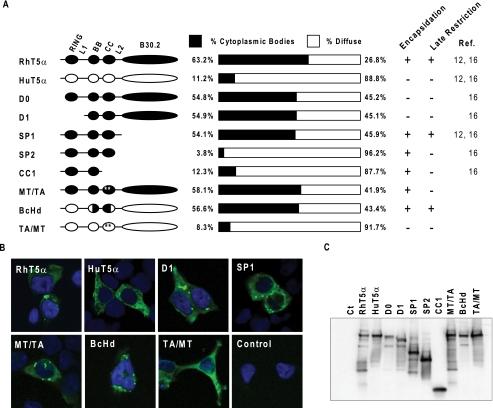

Ability to Form Prominent Cytoplasmic Bodies Can Be Separated from the Late Restriction Activity and the VLP Encapsidation

TRIM5α self-associates to form cytoplasmic bodies (1, 3, 28). Because aggregation of TRIM5α may play a role in the TRIM5αrh-HIV-1 Gag interaction, we examined the possible correlation between the cytoplasmic body formation of the TRIM5α mutants and their VLP encapsidation and late restriction activities. 293T cells were transfected with a TRIM5α expression plasmid, and the localization of C-terminally HA-tagged TRIM5α proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody (Fig. 5, A and B). We defined the TRIM5α protein localization as “cytoplasmic bodies” or “diffuse,” depending on each cell showing more than three discrete cytoplasmic bodies or diffuse cytoplasmic signals with two or less cytoplasmic bodies, respectively. More than 60% of wild-type TRIM5αrh-transfected cells showed multiple typical cytoplasmic bodies, although most TRIM5αhu-transfected cells showed diffused cytoplasmic HA signals. Similarly, diffused cytoplasmic signals were observed in the cells transfected with TRIM5αhu with two point mutations in the coiled-coil domain (TRIM5αhu-TA/MT). In contrast, the TRIM5αhu-BcHd with the B-box 2 and partial coiled-coil domains of TRIM5αrh showed efficient cytoplasmic body formation, comparable with wild-type TRIM5αrh. These results indicate that the TRIM5αrh B-box 2 and coiled-coil domains contain the determinant for the prominent cytoplasmic body formation. This was also supported by our observations that TRIM5αrh-based mutants D0, D1, and SP1, which have deletions in the N-terminal region, RING, or C-terminal B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains, retained the ability to form prominent cytoplasmic bodies. In sharp contrast, most cells transfected with TRIM5αrh mutants CC1 and SP2, which have C-terminal deletions in the coiled-coil, ensuing linker 2 and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains, or the linker 2 and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains, showed diffused cytoplasmic HA signals, similar to TRIM5αhu-transfected cells. Importantly, no correlation was observed between the cytoplasmic body formation and the expression levels of TRIM5αrh proteins (Fig. 5C). We therefore concluded that the coiled-coil domain of TRIM5αrh and the linker 2 region of either TRIM5αrh or TRIM5αhu are required for the efficient cytoplasmic body formation in 293T cells. Our results confirmed the previous report that, unlike the coiled-coil regions of other related TRIM proteins, efficient TRIM5α multimerization and cytoplasmic body formation require the coiled-coil and the linker 2 region (29).

FIGURE 5.

Ability to form prominent cytoplasmic bodies can be separated from the late restriction activity and the VLP encapsidation. 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid-encoding TRIM5α mutant. HA-tagged TRIM5α mutants were detected with a rat anti-HA antibody 3F10 and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody. Nuclei were counter-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Subcellular localization of TRIM5α proteins was determined under confocal microscopy. A, TRIM5α protein localization was tested for prominent cytoplasmic body formation, which was shown as cytoplasmic bodies or diffuse, depending on each cell showing more than three discrete cytoplasmic bodies or diffuse cytoplasmic signals. B, typical subcellular localizations of the TRIM5α mutants are shown. C, 293T cells were transfected with a TRIM5α mutant plasmid, and the TRIM5α expression levels were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. All constructs expressed similar levels of TRIM5α proteins.

In terms of the relationship between the cytoplasmic body formation and VLP incorporation, it is notable that TRIM5αrh mutants D0 and D1 formed large cytoplasmic bodies (Fig. 5) despite their poor encapsidation efficiency (16). Clearly, the prominent cytoplasmic body formation is independent from the efficient encapsidation of TRIM5α proteins. On the other hand, the determinants for the efficient cytoplasmic body formation and the late restriction activity both localized in the coiled-coil and linker 2 domains of TRIM5αrh (Fig. 5) (16). We therefore assessed if these two activities of TRIM5αrh could be separated. As shown in Fig. 5, TRIM5αrh-MT/TA, which has the two point mutations in the coiled-coil domain critical for the late restriction activity, could form cytoplasmic bodies comparable with the wild-type TRIM5αrh. These results indicate that the amino acid residues Met-133 and Thr-146 in the coiled-coil domain do not play a role in the cytoplasmic body formation, and the ability to form prominent cytoplasmic bodies can be separated from the late restriction activity of TRIM5αrh.

DISCUSSION

TRIM5αrh functions as a RING finger-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is self-ubiquitinated by the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5B (3, 30). Although TRIM5αrh and TRIM5αhu proteins are rapidly turned over, rapid degradation of TRIM5α appears unnecessary for its antiretroviral activity against incoming viruses (9, 14, 22). Disruption of TRIM5αrh RING domain impairs, but does not eliminate, the post-entry restriction of HIV-1 infection (8, 12), although proteasome inhibitors do not impair the potency of post-entry restriction (9, 14, 22). By using a RING domain-disrupted mutant and a TRIM21-TRIM5 chimera, we demonstrated that a RING motif, but not the rapid degradation of TRIM5α protein, was required for the late restriction. Proteasome inhibitors failed to impair the late restriction. Although it remains possible that the proteasome system plays some role in the late restriction, these observations indicate that the block of HIV-1 production is largely ubiquitin/proteasome system-independent. Because disruption of the RING motif also resulted in the loss of TRIM5α incorporation into HIV-1 VLPs, it is likely that the RING structure is required for the efficient interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyproteins during viral assembly and that the lack of strong interaction resulted in the loss of late restriction activity of the RING disruption mutant.

Previously, we have demonstrated that the deletion in the first 14 amino acid residues prior to the RING consensus sequence abrogates the efficient VLP encapsidation and the late restriction activity of TRIM5αrh (16). In contrast, TRIM5αrh mutant CC1 with deletion in the C-terminal half of the protein, including the coiled-coil and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains, shows efficient encapsidation, indicating that the coiled-coil and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains are not required for the VLP incorporation (16). In this study, we found that replacement of the partial B-box 2 and coiled-coil domains of TRIM5αhu to their rhesus counterparts led to increased encapsidation of the TRIM5αhu mutant (Fig. 4). In addition, two RBCC domain chimeras, RBCC2 and RBCC3, showed impaired VLP encapsidation, suggesting that the region between the RING domain and its ensuing linker 1 region also plays a role in the efficient encapsidation of TRIM5αrh (Fig. 1). Taken together, we concluded that the N terminus, RING, ensuing linker 1, and the B-box 2 domains of TRIM5αrh determine the encapsidation efficiency. It is conceivable that the proper conformation of TRIM5αrh protein is required for the interaction with HIV-1 Gag in the producer cells.

TRIM5α concentrates in discrete structures in the cytoplasm, designated cytoplasmic bodies (1, 14). Although cytoplasmic body formation may not be required for the post-entry restriction (6), the cytoplasmic bodies are not protein aggregates or inclusion bodies that represent dead-end static structures but rather play a role in TRIM5α function or regulation (17). Importantly, the multimerizing properties of TRIM5α contribute to the formation of cytoplasmic bodies (16). We hypothesized that the multimerization/aggregation of TRIM5αrh might play a key role in the late restriction activity, particularly the interaction with HIV-1 Gag, and we examined whether cytoplasmic body formation of TRIM5α mutants/chimeras correlated with the late restriction activity or efficient encapsidation into HIV-1 VLPs. We found that TRIM5αrh showed more prominent cytoplasmic bodies than TRIM5αhu in 293T cells, and the determinant for the prominent cytoplasmic body formation lay in the coiled-coil domain and the ensuing linker 2 region of TRIM5αrh (Fig. 5). Unexpectedly, the cytoplasmic body formation did not correlate with the late restriction activity or the efficient VLP incorporation. For instance, the TRIM5αrh mutant D0, which lacks the N-terminal 14 amino acid residues and shows impaired VLP incorporation, could form prominent cytoplasmic bodies without showing strong late restriction activity (Fig. 5) (16). On the other hand, the C-terminal deletion mutant CC1, which has deletion in the C-terminal coiled-coil and B30.2(PRYSPRY) domains, demonstrated no prominent cytoplasmic body formation (Fig. 5) but showed efficient VLP encapsidation (16). Indeed, all our TRIM5α mutants with the TRIM5αrh coiled-coil domain and linker 2 region from TRIM5αrh or TRIM5αhu formed prominent cytoplasmic bodies (Fig. 5), whereas the VLP incorporation is dependent on the N-terminal region, RING, and B-box 2 domains. Our results clearly demonstrated that the formation of cytoplasmic bodies, or self-aggregation of TRIM5αrh, can be separated from the efficient VLP encapsidation. Considering that TRIM5α dimers recognize retroviral capsids through direct interactions mediated by the B30.2(PRYSPRY) domain during post-entry restriction (3), it is notable that the coiled-coil-deleted TRIM5αrh mutant CC1 showed efficient VLP incorporation. Because the TRIM5α coiled-coil domain controls protein oligomerization (3, 6, 9, 11), this observation implies that the multimerization of TRIM5αrh is not necessary for the encapsidation and that a TRIM5αrh monomer interacts with HIV-1 Gag polyproteins during the late restriction. We note with interest the recent observation that TRIM15 can block retroviral production (31). Similar to the TRIM5αrh-mediated late restriction, TRIM15 does not require the B30.2(PRYSPRY) or coiled-coil domains of TRIM15 to interact with the murine leukemia virus Gag in the producer cells (31). Thus, recognition of retroviral Gag proteins without forming multimers may be a universal property among TRIM family proteins that affect the late phase of retroviral life cycles.

At present it remains to be determined whether the efficient TRIM5α-HIV-1 Gag interaction or TRIM5α multimerization is required for the potent restriction. Because we have not found any TRIM5α mutant that exhibits potent late restriction activity without showing efficient VLP incorporation or prominent cytoplasmic body formation, we are in favor of the model that the late restriction requires efficient TRIM5α-Gag interaction and multimerization of TRIM5α. From this point of view, it is notable that the TRIM5αrh mutant MT/TA, which has the M133T and T146A substitutions in the coiled-coil domain, showed efficiently VLP incorporation and prominent cytoplasmic body formation without exhibiting potent late restriction activity. This observation indicates that efficient TRIM5α-HIV-1 Gag interaction and multimerization of TRIM5α protein are not sufficient to block HIV-1 production. The residues Met-133 and Thr-146 seem to play a critical role in the late restriction, independent from the VLP incorporation or cytoplasmic body formation activities. Based on these observations, we speculate that the TRIM5αrh-mediated late restriction involves at least two distinct phases as follows: (i) interaction of a TRIM5α monomer with HIV-1 Gag, which depends on the N-terminal, RING, and B-box 2 regions of TRIM5αrh, and (ii) an effector function(s) that depends upon the coiled-coil, especially amino acid residues Met-133 and Thr-146. It is plausible that multimerization of TRIM5αrh, which depends on its coiled-coil domain and linker 2 region, plays a role in the second phase or prior to the second phase of the late restriction.

Previously, we have shown that TRIM5αrh restricts HIV-1 production in a cell line-specific manner. For instance, TRIM5αrh restricts HIV-1 production in 293T or MT4 cells but not in HeLa and TE671 cells, even when TRIM5αrh is overexpressed (16). Given that the cell type specificity is due to the differential expression of a cofactor, it is possible that the TRIM5αrh coiled-coil motif recruits a cofactor during the late restriction through the amino acid residues Met-133 and Thr-146. The possible candidates include other TRIM family protein(s), such as TRIM22 or TRIM21, or a cellular protease. TRIM22 was recently identified to affect HIV-1 production through interaction with HIV-1 Gag polyprotein, and like TRIM5αrh-mediated late restriction, disruption of the RING motif ablates the late restriction activity of TRIM22 (15). Moreover, the type I interferon-responsive TRIM5 and TRIM22 genes share the enhancer region, suggesting a similar transcriptional regulation of the two proteins (16, 20). TRIM21 may also play a role as a cofactor in the late restriction, as it was shown to ubiquitinate TRIM5α (30). Alternatively, TRIM5αrh may recruit a cellular protease during the late restriction. This model is based on our previous observations that TRIM5αrh is cleaved in VLPs in an HIV-1 protease-dependent and -independent manner (12). When TRIM5αrh is incorporated in HIV-1 Gag-Pol particles, HIV-1 protease cleaves TRIM5αrh to produce the truncated 20-kDa form (12). HIV-1 protease inhibitors, Ritonavir and Nelfinavir, can block the formation of the 20-kDa form, but the treatment leads to accumulation of other truncated forms (22 and 28 kDa) of TRIM5αrh in the VLPs (12). Similar to the protease inhibitor treatment, encapsidation of TRIM5αrh in HIV-1 Gag-only particles results in truncation of TRIM5αrh into 22- and 28-kDa forms (12). The 22- and 28-kDa forms are more abundant in VLPs than in producer cells (12). Although the truncation of TRIM5α itself appears to be dispensable for the late restriction (12), these observations suggest the involvement of a cellular protease in the HIV-1 Gag-TRIM5α interaction. Finding a cofactor(s) essential for the late restriction may give us further insights into the mechanism of TRIM5α-mediated late restriction.

In summary, our data have demonstrated that the N-terminal region, RING and B-box 2 domains, determines the interaction between TRIM5αrh and HIV-1 Gag, although the coiled-coil domain and linker 2 region controls the cytoplasmic body formation and the late restriction activity of TRIM5αrh. The self-aggregation of TRIM5α protein itself cannot explain the VLP incorporation or the late restriction activity of TRIM5α. Because all TRIM family proteins have RING, B-box, and coiled-coil domains, it is plausible that a subset of TRIM proteins can recognize/sense synthesized viral proteins in virus-infected cells and play a role in the innate immunity against viral infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Sodroski for pLPCX TRIM5-21R and pLPCX TRIM5αC15A/C18A. The following reagents were obtained through the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID: GHOST(3)R3/X4/R5 cells from Dr. V. N. KewalRamani and Dr. D. R. Littman; pNL4-3 from Dr. M. Martin; pLPCX-TRIM5αrh from Drs. J. Sodroski and M. Stremlau; HIV-1 p24 monoclonal antibody 183-H12-5C from Dr. B. Chesebro and K. Wehrly; and monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 p24 (AG3.0) from Dr. J. Allan.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R56AI074363-01A1 (to Y. I.). This work was also supported by the Mayo Foundation (to Y. I.) and Siebens Ph.D. training fellowship (to S. O.).

- TRIM

- tripartite motif

- HIV-1

- human immunodeficiency virus, type 1

- VLP

- virus-like particle

- HA

- hemagglutinin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reymond A., Meroni G., Fantozzi A., Merla G., Cairo S., Luzi L., Riganelli D., Zanaria E., Messali S., Cainarca S., Guffanti A., Minucci S., Pelicci P. G., Ballabio A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2140–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stremlau M., Owens C. M., Perron M. J., Kiessling M., Autissier P., Sodroski J. (2004) Nature 427, 848–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langelier C. R., Sandrin V., Eckert D. M., Christensen D. E., Chandrasekaran V., Alam S. L., Aiken C., Olsen J. C., Kar A. K., Sodroski J. G., Sundquist W. I. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 11682–11694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stremlau M., Perron M., Lee M., Li Y., Song B., Javanbakht H., Diaz-Griffero F., Anderson D. J., Sundquist W. I., Sodroski J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5514–5519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rold C. J., Aiken C. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Caballero D., Hatziioannou T., Yang A., Cowan S., Bieniasz P. D. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 8969–8978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song B., Javanbakht H., Perron M., Park D. H., Stremlau M., Sodroski J. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 3930–3937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yap M. W., Nisole S., Stoye J. P. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javanbakht H., Diaz-Griffero F., Stremlau M., Si Z., Sodroski J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26933–26940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Sodroski J. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 11495–11502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mische C. C., Javanbakht H., Song B., Diaz-Griffero F., Stremlau M., Strack B., Si Z., Sodroski J. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 14446–14450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakuma R., Noser J. A., Ohmine S., Ikeda Y. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz-Griffero F., Vandegraaff N., Li Y., McGee-Estrada K., Stremlau M., Welikala S., Si Z., Engelman A., Sodroski J. (2006) Virology 351, 404–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Griffero F., Li X., Javanbakht H., Song B., Welikala S., Stremlau M., Sodroski J. (2006) Virology 349, 300–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr S. D., Smiley J. R., Bushman F. D. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakuma R., Ohmine S., Mael A. A., Noser J. A., Ikeda Y. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 235–236, author reply18323834 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell E. M., Dodding M. P., Yap M. W., Wu X., Gallois-Montbrun S., Malim M. H., Stoye J. P., Hope T. J. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2102–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F., Perez-Caballero D., Hatziioannou T., Bieniasz P. D. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 235–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson M. W., Carroll R. G., Stremlau M., Korokhov N., Humeau L. M., Silvestri G., Sodroski J., Riley J. L. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 11117–11128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakuma R., Mael A. A., Ikeda Y. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 10201–10206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mörner A., Björndal A., Albert J., Kewalramani V. N., Littman D. R., Inoue R., Thorstensson R., Fenyö E. M., Björling E. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 2343–2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Caballero D., Hatziioannou T., Zhang F., Cowan S., Bieniasz P. D. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 15567–15572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi A., Gendelman H. E., Koenig S., Folks T., Willey R., Rabson A., Martin M. A. (1986) J. Virol. 59, 284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simm M., Shahabuddin M., Chao W., Allan J. S., Volsky D. J. (1995) J. Virol. 69, 4582–4586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chesebro B., Wehrly K., Nishio J., Perryman S. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 6547–6554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X., Song B., Xiang S. H., Sodroski J. (2007) Virology 366, 234–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y., Li X., Stremlau M., Lee M., Sodroski J. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 6738–6744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song B., Diaz-Griffero F., Park D. H., Rogers T., Stremlau M., Sodroski J. (2005) Virology 343, 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javanbakht H., Yuan W., Yeung D. F., Song B., Diaz-Griffero F., Li Y., Li X., Stremlau M., Sodroski J. (2006) Virology 353, 234–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamauchi K., Wada K., Tanji K., Tanaka M., Kamitani T. (2008) FEBS J. 275, 1540–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchil P. D., Quinlan B. D., Chan W. T., Luna J. M., Mothes W. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X., Li Y., Stremlau M., Yuan W., Song B., Perron M., Sodroski J. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 6198–6206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]