Abstract

The transcription factor SNAIL1 is a master regulator of epithelial to mesenchymal transition. SNAIL1 is a very unstable protein, and its levels are regulated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP1 that interacts with SNAIL1 upon its phosphorylation by GSK-3β. Here we show that SNAIL1 polyubiquitylation and degradation may occur in conditions precluding SNAIL1 phosphorylation by GSK-3β, suggesting that additional E3 ligases participate in the control of SNAIL1 protein stability. In particular, we demonstrate that the F-box E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXl14 interacts with SNAIL1 and promotes its ubiquitylation and proteasome degradation independently of phosphorylation by GSK-3β. In vivo, inhibition of FBXl14 using short hairpin RNA stabilizes both ectopically expressed and endogenous SNAIL1. Moreover, the expression of FBXl14 is potently down-regulated during hypoxia, a condition that increases the levels of SNAIL1 protein but not SNAIL1 mRNA. FBXL14 mRNA is decreased in tumors with a high expression of two proteins up-regulated in hypoxia, carbonic anhydrase 9 and TWIST1. In addition, Twist1 small interfering RNA prevents hypoxia-induced Fbxl14 down-regulation and SNAIL1 stabilization in NMuMG cells. Altogether, these results demonstrate the existence of an alternative mechanism controlling SNAIL1 protein levels relevant for the induction of SNAIL1 during hypoxia.

Keywords: Cancer, Cell/Migration, Protein/Degradation, Protein/Stability, Transcription/Zinc Finger, Tumor, Hypoxia, SNAIL1

Introduction

The human SNAIL family of zinc finger transcription factors, composed of SNAIL1 and SNAIL2 (also called SNAIL and SLUG, respectively) plays a fundamental role in initiating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT),6 a key developmental program that results in the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics by epithelial cells (1). EMT is required for essential processes, such as gastrulation and formation of neural crest cells, and is also relevant in pathological processes, such as fibrosis, cancer cell invasion, and hypoxia (1–4). Expression of SNAIL1 induces a more invasive phenotype, at least in part through its inhibition of E-cadherin gene expression (2). SNAIL1 represses transcription of E-cadherin by binding to three E-boxes present in the human E-cadherin promoter (5). Moreover, SNAIL1 has additional cellular functions independent of EMT, because it confers resistance to cell death (6–8).

SNAIL1 is a highly unstable protein and is very sensitive to proteasome inhibitors (9). SNAIL1 degradation by the proteasome requires its interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP1/FBXW1 and the subsequent ubiquitylation of SNAIL1 protein (9). β-TrCP1/FBXW1, like β-TrCP2/FBXW11, recognizes the destruction motif DpSXXpS (where pS represents phosphoserine) and participates in the degradation of many substrates, including β-catenin (10, 11). Before its interaction with β-TrCP1/FBXW1, SNAIL1 degradation requires nuclear GSK-3β (glycogen synthase kinase-3β) phosphorylation. This modification unmasks a nuclear export sequence (NES) and promotes SNAIL1 export from the nucleus (12). In the cytosol, SNAIL1 undergoes a second phosphorylation by GSK-3β, which targets the protein for β-TrCP1-mediated cytoplasmic degradation (9). Activation of AKT or Wnt signaling inhibits SNAIL1 phosphorylation, increasing SNAIL1 protein levels (13).

However, inactivation of GSK-3β does not always increase the stability of SNAIL1. In this paper, we demonstrate that SNAIL1 protein degradation can be regulated independently of phosphorylation by GSK-3β. We report that the human ortholog of Ppa (Partner of Paired), an F-box protein that regulates Snail2 protein during Xenopus laevis development (14), controls SNAIL1 protein stability in mammalian cells. We also demonstrate that SNAIL1 protein is stabilized during hypoxia concomitantly with a strong FBXL14 mRNA down-regulation, showing that the SNAIL1-FBXL14 interaction is physiologically relevant.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Hypoxia Induction

HEK293T, MCF-7, MiaPaCa-2, SW620, NMuMG, and NIH3T3 were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) or obtained from our institute cell bank. The generation and characteristics of human intestinal HT-29 M6 cells transfected with Snail1-HA have been previously described (5). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 10 μg/ml insulin (NMuMG cells) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Oxygen deprivation was carried out in an incubator with 1% O2, 5% CO2, and 96% N2 for 72–96 h. When indicated, cells were treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (PeproTec) for 4 days.

Construction of Expression Vectors

The pcDNA3-Snail1- HA, Snail1SA-HA, Snail1SD-HA, and GFP-Snail1 constructs were described previously (5, 12). The FBXL14 cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR from 1 μg of RNA of RWP-1 cells (One-Step kit; Invitrogen) with primers FB-1F and FB-1R, containing a Kozak start site and BamHI and EcoRV restriction sites, respectively, and cloned into BamHI/EcoRV-digested pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) carrying an HA epitope and into pcDNA3.1-Myc-HisA. The F-box deletion mutant of FBXL14 (ΔF) was obtained using the forward primer FB-2F(ΔF), including a BamHI restriction site and FB-1R oligonucleotide. The BamHI/NotI FBXL14-HA insert was subcloned into pGEX6P1 to produce recombinant GST-FBXL14. The sequence of the oligonucleotides is indicated in supplemental Table 1.

SNAIL1 point mutants were obtained as described previously (7), using the primers shown in supplemental Table 1. All constructs were verified by sequencing in both directions.

Transfection, Cell Lysis, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blotting

For SNAIL1-HA degradation assays, cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h and transfected with 250 ng of Snail1-HA and 0.5–1.2 μg of FBXL14-Myc, the ΔF deletion mutant, β-TrCP1, or β-TrCP2. When indicated, GFP was used as internal transfection control. Cells were harvested after 24 h, and total extracts were obtained using total lysis buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 25% glycerol, 420 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitors) for 30 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. For immunoprecipitation experiments, total cell extracts were obtained with immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors) and precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4 °C. Clarified supernatants were incubated with rabbit anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitation of endogenous SNAIL1 was performed with affinity-purified polyclonal antibody anti-SNAIL1 (Abcam) and detection with an anti-SNAIL1 monoclonal antibody (15). Immunocomplexes were recovered on protein A-Sepharose beads overnight at 4 °C and analyzed by Western blot using the antibodies mentioned in the supplemental material.

To determine in vivo ubiquitylation, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated vectors and lysed 24 h after transfection with 0.5 ml of immunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing 1% SDS. Cleared lysates were diluted 10-fold before immunoprecipitation. When indicated, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (50 μm) was added 5 h before cell lysis. Alternatively, cells transfected with His-tagged ubiquitin were lysed in denaturing lysis buffer at pH 8.0 (6 m guanidinium HCl, 100 mm phosphate buffer, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 5 mm imidazole, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitors). The lysates were sonicated and incubated with equilibrated Ni2+-agarose affinity chromatography beads for 3 h at room temperature. The beads were washed once in wash buffer at pH 8.0 (8 m urea, 100 mm phosphate buffer, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 5 mm imidazole, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol) and then washed three times in wash buffer at pH 6.3 (prepared like wash buffer at pH 8.0 with Tris-HCl at pH 6.3). The beads were washed with phosphate-buffered saline solution, eluted in Laemmli sample buffer, and analyzed by Western blot.

RNA Interference

Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against human FBXL14 mRNA were designed using a small interfering RNA selection program (16). Selected oligonucleotides containing target sequences were cloned into pSUPER-Neo-IRES-GFP using 5′-BglII and 3′-XhoI. The sequence of the oligonucleotides is shown in supplemental Table 1 (oligonucleotides FB-si-1 to -4). Plasmids were stably transfected in SW620 cells as indicated above and selected with G418 (1 mg/ml) during 3 weeks. A pool of cells expressing high GFP levels was sorted by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. The efficiency of mRNA down-regulation was assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. For gene silencing of Fbxl14 (mouse) or TWIST1 (mouse and human) in NMuMG and SW620 cells, the MISSION® shRNA plasmids (Sigma) were used to produce lentiviral particles. After transduction, stable cell lines expressing the shRNA were isolated by puromycin selection. Other methods are described in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

SNAIL1 Degradation Can Occur Independently of Phosphorylation by GSK-3β

Phosphorylation by GSK-3β is required for SNAIL1 to be exported from the nucleus and labeled for ubiquitylation by the E3 ligase complex SCF-β-TrCP1 in the cytoplasm. Accordingly, SNAIL1 levels on stably transfected HEK293 and MCF-7 cells are sensitive to the addition of the GSK-3β inhibitor LiCl (9). We analyzed the effect of LiCl on SW620, MiaPaCa-2, and NIH3T3 cell lines that express moderate to high levels of endogenous SNAIL1 (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis showed that the addition of LiCl for 6 h to the cell medium only modestly increased SNAIL1 stability in SW620 cells, whereas the three cell lines were much more responsive to the addition of proteasome inhibitors, such as MG132 (Fig. 1A, left). Similar results were obtained after increasing the time of treatment with LiCl or using the GSK-3β inhibitor SB216763 (not shown). Quantification of these results indicated that MG132 increased SNAIL1 protein 5-fold in MiaPaCa-2 cells, whereas LiCl did not modify it (Fig. 1A, right); a higher stimulation of SNAIL1 by MG132 with respect to LiCl was also detected in SW620, NIH3T3 (Fig. 1A), NMuMG, and RWP-1 cells (not shown). As a positive control, the levels of β-catenin, a well known substrate of GSK-3β and β-TrCP1, were highly up-regulated by both LiCl (22-fold) and MG132 (25-fold) in MiaPaCa-2 cells (Fig. 1A). The absence of β-catenin stimulation in NIH3T3 or SW620 by these compounds is due to the high stability of this protein because of the lack of the elements needed for β-catenin phosphorylation by GSK-3β and further degradation (17).

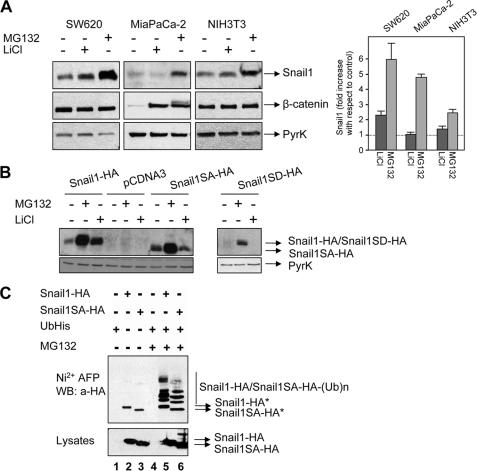

FIGURE 1.

SNAIL1 degradation and ubiquitylation may occur independently of phosphorylation by GSK-3β. A, cells were treated with 50 mm LiCl or 50 μm MG132 for 6 h, and SNAIL1 expression levels were analyzed by Western blot using total cell extracts (left). β-Catenin was analyzed as a positive control of LiCl stabilization. Analysis of pyruvate kinase (PyrK) was used as a control of equal loading. The right panel corresponds to the densitometric analysis of the SNAIL1 blots obtained in different experiments. SNAIL1 protein was normalized in reference to an internal control (pyruvate kinase), and the stimulation by MG132 and LiCl was measured with respect to SNAIL1 protein levels in non-treated cells. The average of two or three experiments ± range is shown. B, HEK293T cells stably transfected with the indicated SNAIL1 forms were analyzed after treatment with LiCl or MG132 as above. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA or SNAIL1SA-HA and a ubiquitin-His plasmid. After 24 h, cells were treated with MG132 when indicated to stabilize ubiquitylated proteins that were purified using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography (Ni2+-AFP). Bound proteins were blotted against HA, and ubiquitylated SNAIL1 was detected as a ladder of high molecular weight bands. Non-ubiquitylated SNAIL1-HA was nonspecifically bound to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads and is labeled with an asterisk. In the lower panel, total cell extracts were used to evaluate the relative expression of transfected proteins prior to purification (input).

We also analyzed the stability of the mutants SNAIL1SA and SNAIL1SD, where the 14 serine residues of the serine-rich domain (SRD), including those phosphorylated by GSK-3β, were mutated to alanines or aspartic acids, respectively (12). As expected, wild type (WT) SNAIL1 but not the SNAIL1SA or SNAIL1SD mutants was stabilized by LiCl (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, SNAIL1SA, unable to be phosphorylated by GSK-3β, was markedly stabilized by MG132, suggesting that this mutant is sensitive to proteasome degradation independent of phosphorylation by GSK-3β (Fig. 1B). A similar behavior of SNAIL1SA and SNAIL1SD mutants (stabilization by MG132 but not by LiCl) was also observed in other cell lines (not shown). The GSK-3β-insensitive SNAIL1SA mutant could also be polyubiquitylated in vivo in a very similar fashion to the WT protein. In these assays, we transfected the two SNAIL1 forms together with ubiquitin-His and purified ubiquitylated proteins by Ni2+-agarose chromatography (Fig. 1C). Upon the addition of the proteasomal inhibitor MG132, a ladder corresponding to the differently ubiquitylated SNAIL1 was detected, both for SNAIL1 WT and the SA mutant (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6). These experiments demonstrate that SNAIL1 can be ubiquitylated independently of phosphorylation by GSK-3β and suggest that there may be other E3 ligases apart from β-TrCP1 playing a role in SNAIL1 degradation.

SNAIL1 Interacts with the F-box Protein FBXL14

It has been reported that during the development of X. laevis embryos, Snail2 is degraded by the SCF ubiquitin ligase Ppa (14). Interestingly, the Snail2-Ppa interaction is phosphorylation-independent. We reasoned that a ppa homologue may also be involved in SNAIL1 phosphorylation-independent degradation in mammalian cells. Therefore, we cloned the human homologue of ppa, called FBXL14 (NCBI GeneID: 144699), an F-box protein containing six leucine repeats. FBXL14 and Ppa share a high degree of homology, differing only in their N-terminal part (not shown). In order to demonstrate the possible association of SNAIL1 and FBXL14, we co-transfected HA-tagged SNAIL1 (WT, SA, or SD mutants) and FBXL14-Myc. In cells pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, FBXL14 was detected in the immunoprecipitates obtained with an anti-HA antibody, an epitope tagging the three SNAIL1 forms (Fig. 2A), indicating that the WT protein and the SA and SD mutants can bind to FBXL14 and suggesting that the interaction does not depend on the phosphorylation status of the SRD SNAIL1 domain. This is in striking contrast with the interaction of SNAIL1 with β-TrCP1 because this ubiquitin ligase only immunoprecipitated with SNAIL1 WT and not with SNAIL1SA (Fig. 2B). FBXL14-Myc also interacted with endogenous SNAIL1, as determined by co-immunoprecipitation experiments in NIH3T3 cells treated with MG132. FBXL14-Myc was detected in the SNAIL1 immunocomplex when a specific SNAIL1 antibody was used but not with an irrelevant antibody (IgG), indicating that endogenous SNAIL1 also associates with FBXL14-Myc (Fig. 2C).

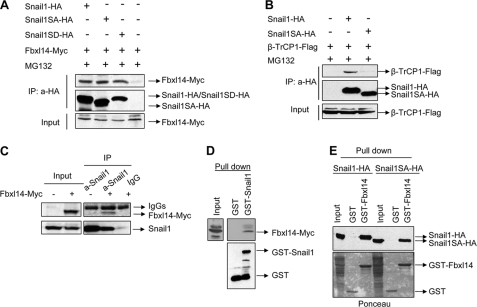

FIGURE 2.

SNAIL1 interacts with FBXL14. A, co-immunoprecipitation of FBXL14-Myc and SNAIL1. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated SNAIL1 mutants and FBXL14 in pcDNA3 expression plasmid for 24 h; cells were treated with MG132 (50 μm) for 6 h. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a rabbit anti-HA antibody and blotted against mouse anti-Myc or rat anti-HA antibodies. Expression levels of FBXL14-Myc are indicated in the lower panel (Input). B, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and immunoprecipitated as in A. Immunocomplexes were analyzed with mouse anti-FLAG or rat anti-HA antibodies. The lower panel shows expression of β-TrCP1 in the extracts (Input). C, NIH3T3 cells expressing high levels of endogenous SNAIL1 were transiently transfected with FBXL14-Myc (Input, left panel); total cell extracts were obtained and immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-SNAIL1 or control IgGs and analyzed with an anti-SNAIL1 or anti-Myc monoclonal antibody. D and E, pull-down assays were carried out using cell extracts from HEK293T cells transiently transfected with FBXL14-Myc (D) or SNAIL1-HA and SNAIL1SA-HA (E). Glutathione-Sepharose-bound proteins were analyzed with anti-Myc (D) or anti-HA (E). As a control, recombinant fusion proteins were visualized with anti-GST antibodies or Ponceau S staining.

To further confirm that the interaction between SNAIL1 and FBXL14 does not require SNAIL1 phosphorylation, we performed pull-down assays using a GST-SNAIL1 fusion protein and cell extracts from FBXL14-Myc-transfected cells. As shown in Fig. 2D, FBXL14-Myc specifically associated with GST-SNAIL1 but not with GST alone. This contrasts with the fact that β-TrCP1 has been shown to bind GST-SNAIL1 only after in vitro phosphorylation by GSK-3β (9). We also performed the reverse experiment, pulling down transfected SNAIL1 using recombinant GST-FBXL14. A strong interaction was observed between FBXL14 and SNAIL1, both WT and the GSK-3β-insensitive mutant SNAIL1SA (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these observations suggest that FBXL14 and SNAIL1 may form a complex in vivo and that the interaction does not require SNAIL1 phosphorylation in the SRD.

SNAIL1 Stability Is Decreased by FBXL14 but Not by a Mutant Lacking the F-box Domain

To examine if FBXL14 affects SNAIL1 stability in vivo, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with vectors encoding SNAIL1-HA and FBXL14-Myc. As control, we used a mutant lacking the F-box domain (ΔF), the sequence required to interact with the SCF (SKP1-CULLIN1-RBX1) complex (18). As shown in Fig. 3A, transfection of full-length FBXL14 but not the ΔF mutant promoted SNAIL1 protein down-regulation in a dose-dependent manner. SNAIL1 levels decreased more than 80% at the highest FBXL14 concentration (Fig. 3A, lane 5) with respect to the controls, cells without FBXL14 (lane 1), or cells transfected with the inactive FBXL14 mutant (lane 8). Interestingly, the low levels of FBXL14 observed at the highest concentration suggested that FBXL14 is targeting itself to degradation at high doses (Fig. 3A). This is confirmed by the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132, which completely prevented SNAIL1 degradation and increased FBXL14 levels (Fig. 3B). Finally, decay of SNAIL1 levels in cycloheximide (CHX)-treated cells was also accelerated in the presence of FBXL14 with respect to the ΔF mutant (Fig. 3C).

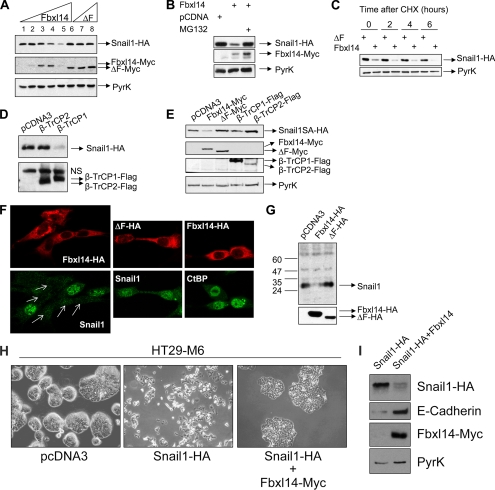

FIGURE 3.

SNAIL1 levels are regulated by FBXL14. A, dose-dependent degradation of SNAIL1-HA with FBXL14. HEK293T cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA (lane 1; 0.25 μg) and increasing concentrations of FBXL14-Myc (lanes 2–5; 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 μg, respectively) or the ΔF mutant (lanes 6–8; 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 μg, respectively). SNAIL1-HA protein levels were evaluated 24 h after transfection by Western blot with anti-HA antibody (top). In the middle and lower panels, the blot was analyzed with anti-Myc (for FBXL14) and anti-pyruvate kinase (loading control), respectively. B, degradation of SNAIL1 by FBXL14 is prevented by the MG132 proteasome inhibitor. Cells were transfected as in A and treated with MG132 (50 μm) for 6 h prior to cell lysis. Western blotting was carried out with antibodies against HA (top), Myc (middle), and pyruvate kinase (bottom). C, different effect of FBXL14 and ΔF mutant on SNAIL1 stability. SNAIL1-HA was transiently co-transfected with FBXL14-Myc or the ΔF mutant at the highest concentration indicated in A. At 24 h, cells were treated with CHX, and cell extracts were prepared after 0, 2, 4, or 6 h and analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. D, cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA and β-TrCP1 or β-TrCP2 (1.2 μg), and relative levels were evaluated 24 h later by Western blotting. The upper band in the anti-FLAG Western blot (NS) corresponds to a nonspecific band also detected in the non-transfected extracts. E, the SNAIL1SA mutant is resistant to β-TrCP1 but not to FBXL14 degradation. The SNAIL1SA-HA mutant was co-transfected with the indicated plasmids, and extracts were analyzed using antibodies against HA (SNAIL1; top), Myc (FBXL14 and ΔF mutant; middle top), FLAG (β-TrCP1 or β-TrCP2; middle bottom), and pyruvate kinase (bottom). F, NIH3T3 cells were transiently transfected with FBXL14-HA (upper left), and endogenous SNAIL1 were detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody against SNAIL1 (lower left) by confocal microscopy. Note that in cells transfected with FBXL14 (arrows), SNAIL1 expression is depleted with respect to non-transfected cells. Transfection of the ΔF mutant (upper middle) does not have an effect on SNAIL1 expression (lower middle). Transfected FBXL14 and ΔF were detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against HA. FBXL14 transfection (upper right) and staining with CtBP antibodies (lower right) were carried out as a control of nonspecific degradation. G, a pool of NIH3T3 cells transfected as in F was analyzed by Western blot with mouse anti-SNAIL1 (top) or anti-HA antibodies (bottom). H and I, FBXL14 overexpression reverses the SNAIL1-induced mesenchymal phenotype. HT29-M6 cells stably expressing SNAIL1-HA or a control plasmid were transfected with pcDNA3-FBXL14-Myc or with control empty vector. H, a representative micrograph of the cell populations obtained is shown. The phenotype of HT29-M6-SNAIL1-HA cells transfected with FBXL14 was similar to that presented here for control HT29-M6 cells. FBXL14-Myc, SNAIL1-HA, and E-cadherin expression were determined by Western blotting (I). Determination of pyruvate kinase (PyrK) was used as a normalization control.

We also compared the effects of FBXL14, β-TrCP1, and β-TrCP2 on SNAIL1 stability. As shown in Fig. 3D, transfection of β-TrCP1 but not that of β-TrCP2 decreased SNAIL1 levels. This down-regulation was not observed with SNAIL1SA. Co-transfection of SNAIL1SA with β-TrCP1, β-TrCP2, FBXL14, or the ΔF mutant indicated that only FBXL14 severely decreased SNAIL1SA protein levels, whereas the ΔF mutant caused minor stabilization (Fig. 3E).

We further verified the role of FBXL14 using NIH3T3 cells, a cell type that expresses endogenous SNAIL1 mainly in the nucleus (Fig. 3F). As seen by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3F, upper left panel), FBXL14-HA was mainly detected in the cytoplasm. Cells expressing the ubiquitin ligase, labeled with arrows in the lower left panel of Fig. 3F showed markedly decreased endogenous SNAIL1 levels when compared with non-transfected cells in the same field of view. On the contrary, SNAIL1 expression was unaffected by the ΔF mutant (Fig. 3F, middle panels). As a control and to rule out a nonspecific effect, we verified that FBXL14 transfection did not modify the levels of the nuclear co-repressor CtBP (Fig. 3F, right panels). The down-regulation of endogenous SNAIL1 expression was also observed when we compared the levels of this protein by Western blot in NIH3T3 cells stably expressing FBXL14 with cells transfected with the empty vector or the ΔF mutant (Fig. 3G).

We also analyzed whether FBXL14 was able to revert the morphological effects of SNAIL1 transfection in epithelial cells. We used human colon cancer HT29-M6 cells engineered to express SNAIL1-HA (HT29-M6-SNAIL1-HA) that exhibit a fibroblastic phenotype as described previously (Fig. 3H, middle) (5). Expression of FBXL14 induced the reacquisition of a more compact phenotype (Fig. 3H, right), resembling the morphology of the control untransfected cells (not shown) or transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 3H, left). In parallel, the levels of ectopic SNAIL1-HA levels were decreased, and the epithelial marker E-cadherin was up-regulated by FBXL14 transfection (Fig. 3I). This result indicates that FBXL14 expression is able to, at least partially, reverse a SNAIL1-dependent EMT.

The SNAIL1 N-terminal Domain Is Required for FBXL14-mediated Degradation

We analyzed the SNAIL1 domain involved in the sensitivity to FBXL14, co-transfecting this ubiquitin ligase with GFP fusion proteins containing SNAIL1 N- or C-terminal domains (SNAIL1-NT, comprising amino acids 1–151, and SNAIL1-CT, comprising amino acids 152–264). As shown in Fig. 4A, SNAIL1-NT but not SNAIL1-CT was affected by FBXL14 expression; levels of GFP-SNAIL1-NT were decreased by FBXL14 either in the presence or absence of CHX (compare lanes 1 and 2 or lanes 3 and 4). To further map the N-terminal elements involved in degradation, we co-transfected different SNAIL1 N-terminal deletion mutants together with FBXl14. As shown in Fig. 4B, a mutant in which the SRD had been removed (Δ90–120) was also down-regulated by FBXL14, further suggesting that the GSK-3β target sequence is not required for FBXL14 degradation. A SNAIL1 protein encompassing the SRD and the NES (N-terminal mutant 82–151) was sensitive to FBXL14 expression. The effect of the ubiquitin ligase was much lower on two mutants where the last 14 amino acids of the N-terminal domain had been removed (comprising amino acids 1–138 or 82–138). All together, these results suggest that amino acids 120–151 are important for FBXL14-triggered degradation of SNAIL1 protein.

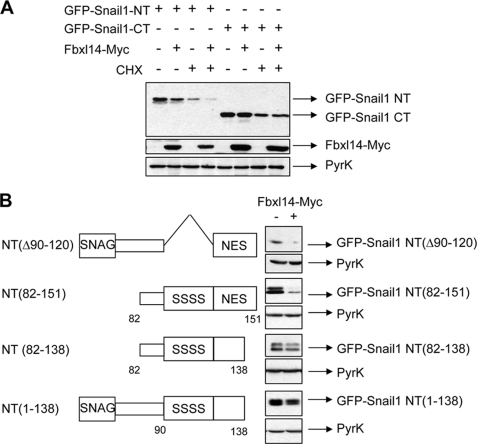

FIGURE 4.

The N-terminal domain of SNAIL1 is required for FBXL14 degradation. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with SNAIL1 constructs containing the N-terminal (NT) or the C-terminal (CT) domain fused to GFP plus FBXL14-Myc. Cells were left untreated or treated with CHX for 6 h and lysed. Western blotting was performed with rabbit anti-GFP (top), anti-Myc (middle), and anti-pyruvate kinase as loading control (bottom). B, cells were transfected with SNAIL1 N-terminal truncation mutants together with FBXL14 (+) or empty vector (−). Expression of the SNAIL1 fusion proteins was determined by Western blot with anti-GFP antibody. The double band detected for the SNAIL1 fusion proteins containing the SRD corresponds to the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of this protein that were similarly degraded by FBXL14.

SNAIL1 Is Ubiquitylated by FBXL14

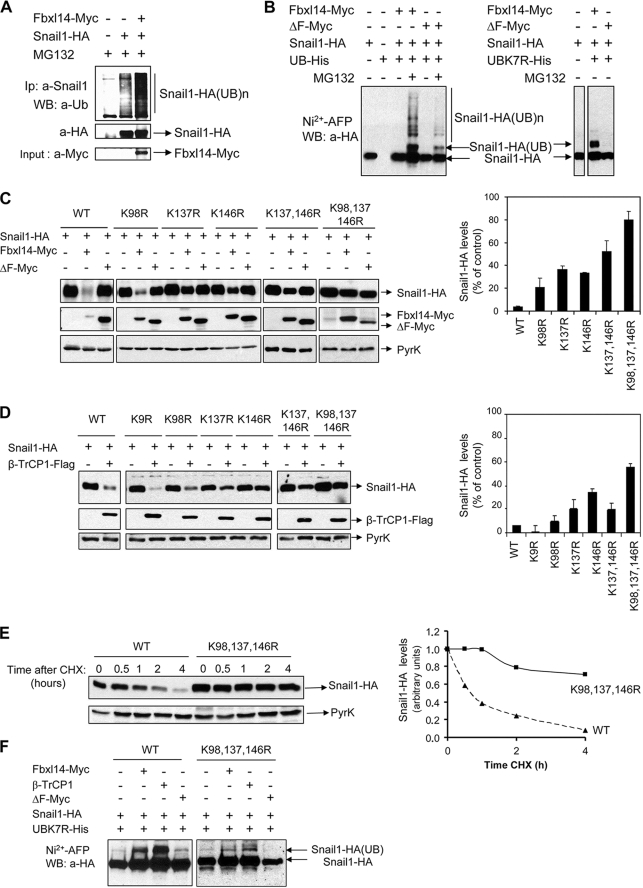

We performed in vivo ubiquitylation experiments to investigate if FBXL14 stimulates SNAIL1 ubiquitylation. SNAIL1-HA was expressed in HEK293T cells for 24 h, and MG132 was added 6 h before cell harvesting to stabilize ubiquitylated proteins. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with SNAIL1 under denaturing conditions to ensure that other ubiquitylated proteins were not associated with SNAIL1, and immunocomplexes were analyzed with anti-ubiquitin antibody. As shown in Fig. 5A, co-transfection of FBXL14 increased the amount of polyubiquitylated SNAIL1 (SNAIL1-HA(UB)n), detected as a ladder of differently modified SNAIL1 protein with respect to the control without FBXL14. Similar experiments were performed co-expressing ubiquitin-His and SNAIL1-HA, purifying ubiquitylated proteins using Ni2+-agarose affinity chromatography beads and analyzing SNAIL1 by Western blot (Fig. 5B). Ubiquitylated SNAIL1 was detected as a mix of mono- and polyubiquitylated forms in the presence of FBXL14. These forms were not observed in cells that had not been pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Importantly, formation of polyubiquitylated SNAIL1 was much lower in cells transfected with the ΔF mutant, indicating that the integrity of this protein is required for the modification of SNAIL1 (Fig. 5B, left). Similar results were obtained with a polyubiquitylation-deficient ubiquitin mutant, UbiK7R, in which the 7 lysines have been replaced by arginines (Fig. 5B, right). The UbiK7R mutant does not support proteasome degradation, and modified proteins only incorporate one ubiquitin molecule (19). In the presence of the UbiK7R mutant, ubiquitylated SNAIL1, visualized as a single band and labeled SNAIL1-HA(UB), was only detected when FBXl14 was co-expressed (Fig. 5B, right) and not with the ΔF mutant.

FIGURE 5.

SNAIL1 is ubiquitylated by FBXL14 through lysines 98, 137, and 146. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA and FBXL14. Cells were treated with MG132, and total cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-SNAIL1 monoclonal antibody under denaturing conditions. Polyubiquitylated SNAIL1 (Snail1-HA(UB)n) or unmodified SNAIL1 were detected in the immunoprecipitate using polyclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody (top) or anti-HA (middle). FBXL14 expression was evaluated in cell extracts (bottom). B, left, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and treated with MG132 when shown. Ubiquitylated proteins were purified by affinity chromatography with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Ni2+-AFP), and bound proteins were analyzed with anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitylated SNAIL1. Right, cells were transfected as indicated with the polyubiquitylation-deficient mutant ubiquitin K7R-His (UBK7R). Note that when using the UBK7R mutant, ubiquitylated SNAIL1 was detected as a single band. C and D, putative lysine ubiquitylation sites of SNAIL1 were mutated to arginines, and mutants were transfected together with FBXL14, the ΔF mutant (C), or β-TrCP1 (D) at conditions where complete WT SNAIL1 degradation was obtained. The left panels show representative results of the analyses of SNAIL1-HA, ΔF/FBXL14-Myc, and β-TrCP1-FLAG by Western blot. The right panels present the average ± S.D. of the densitometric analyses of SNAIL1-HA signal in three independent experiments. E, the kinetics of degradation of K98R,K137R,K146R SNAIL1 compared with WT were determined after the addition of CHX. The right panel corresponds to the densitometric analysis of a representative experiment. F, ubiquitylation of K98R,K137R,K146R SNAIL1 compared with WT was determined after transfection of the indicated plasmids as in Fig. 5B (right). The arrows point to the migration of SNAIL1 and ubiquitylated SNAIL1 as determined by Western blot.

We also analyzed the lysines that participate in this process. The N-terminal domain of SNAIL1 contains five conserved lysines (Lys9, Lys16, Lys98, Lys137, and Lys146). Lys137 and Lys146 are contained in the sequence that was characterized as being responsive to FBXl14 (amino acids 120–151). Mutation of lysines 9 and 16 to arginines did not affect SNAIL1 stability (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5C, the SNAIL1 K98R mutant was as sensitive to FBXL14 transfection as the WT protein. The SNAIL1 K137R and SNAIL1 K146R mutants (or a mutant bearing both mutations) presented a lower sensitivity to FBXL14 co-expression, although they were still down-regulated. Total resistance to FBXL14 required simultaneous replacement of lysines 98, 137, and 146 by arginines (Fig. 5C), suggesting that these three lysines may be participating in the degradation targeted by FBXL14.

Because the lysines that mediate β-TrCP1-dependent degradation of SNAIL1 have not yet been characterized, we performed similar experiments using β-TrCP1 instead of FBXL14 (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, β-TrCP1 seems to use the same pattern of lysines as FBXL14, a result suggested by the higher resistance to degradation presented by the K98R,K137R,K146R SNAIL1 mutant. To further confirm the relevance of these lysines to SNAIL1 stability, we analyzed the stability of the SNAIL1 triple mutant compared with WT SNAIL1 after the CHX addition. As shown in Fig. 5E, the K98R,K137R,K146R mutant was very stable, and 80% of SNAIL1 protein could still be detected after 4 h of CHX treatment. According to these results, the in vivo ubiquitylation (determined after co-transfection with the UbiK7R mutant) of the SNAIL1-HA triple mutant in the presence of both FBXL14 and β-TrCP1 was significantly impaired when compared with that of SNAIL1-HA WT (Fig. 5F). Interestingly, a residual ubiquitylation band was still observed in the triple mutant, probably indicating that other lysines could have a minor role. Therefore, FBXLl4 and β-TrCP1 target SNAIL1 degradation through ubiquitin modification of lysines 98, 137, and 146.

FBXL14 Depletion Stabilizes SNAIL1 Protein

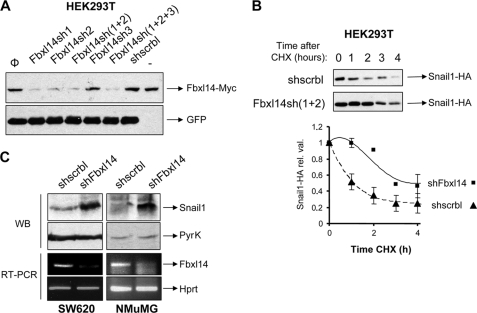

FBXL14 is expressed in most cell lines studied as determined by RT-PCR (not shown). We analyzed whether SNAIL1 levels were sensitive to depletion of endogenous FBXL14 using RNA interference. Three shRNAs were designed against human FBXL14, cloned into pSUPER-Neo-IRES-GFP vector, and tested for their effect on exogenous FBXL14 levels after transient transfection in HEK293T cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, FBXL14-sh1 and -sh2 but not FBXL14-sh3 were very efficient in depleting exogenous FBXL14 levels when compared with a control shRNA (shscrbl) and were used in further experiments. We measured the half-life of exogenous SNAIL1-HA transiently transfected in HEK293T cells in the presence of shFBXL14 (sh1 and sh2) after adding CHX. As shown in Fig. 6B, the half-life of transfected SNAIL1-HA was ∼1 h in cells co-transfected with the control shRNA, whereas it increased up to 3 h in cells transfected with FBXL14-sh1 and -sh2.

FIGURE 6.

FBXL14 inhibition increases SNAIL1 protein stability. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with FBXL14-Myc, and different combinations of FBXL14-shRNAs were cloned into pSUPER-Neo-IRES-GFP or a scrambled shRNA as control. Exogenous FBXL14 protein expression (top) was determined by Western blot after 48 h; GFP protein levels (bottom) were analyzed as transfection control. B, top, cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA and a combination of FBXL14 shRNAs (sh1 + 2) that gave maximal inhibition of exogenous FBXL14. SNAIL1-HA protein was analyzed at different times after the CHX addition. The average ± S.D. of the densitometric analysis of three independent experiments is shown in the lower panel. C, FBXL14 shRNAs or the scrbl control were stably transfected in SW620 and NMuMG cell lines. Expression of endogenous SNAIL1 protein was determined by Western blot (WB) with a specific monoclonal antibody. FBXL14 mRNA inhibition was assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Determination of pyruvate kinase (PyrK) and HPRT were used as normalization controls in the Western blot and RT-PCR assays, respectively.

To evaluate the importance of FBXL14 in the regulation of endogenous SNAIL1 levels, we tested the effect of FBXL14 interference in human cancer SW620 cells. As shown in Fig. 6C, stable transfection of FBXL14-sh2 in these cells decreased FBXL14 RNA levels by 80% (estimated by semiquantitative RT-PCR) and resulted in a significant increase of endogenous SNAIL1 (∼2.9-fold) compared with cells transfected with an shRNA control (shscrbl). Similar results were obtained in mouse NMuMG cells, a cell line derived from normal mouse mammary epithelial cells using a set of commercial shRNAs (see “Experimental Procedures”) (Fig. 6C). Stable infection of shRNAs against Fbxl14 in NMuMG cells also resulted in an up-regulated expression of SNAIL1 (Fig. 6C). In this case, the -fold increase could not be determined because SNAIL1 was barely detected in control NMuMG cells. All of these experiments suggest that SNAIL1 levels are directly dependent on FBXL14 expression.

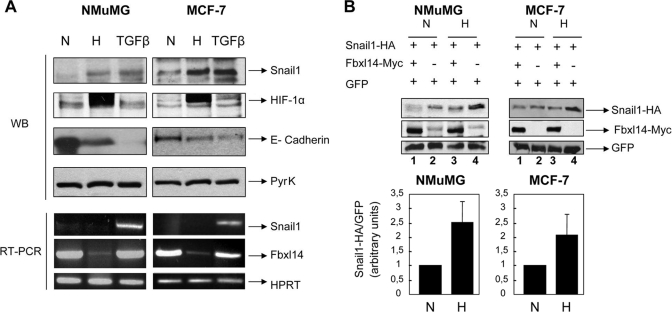

FBXL14 Is Down-regulated during Hypoxia

We wanted to study the role of FBXL14 in two physiological models of EMT: TGF-β1 treatment and hypoxia (Fig. 7). SNAIL1 protein expression was stimulated by incubation of NMuMG cells with TGF-β1, as previously reported (20, 21). Exposure of these cells to low O2 concentrations (hypoxia (H)) induced a similar increase in SNAIL1 protein when compared with control samples (normoxia (N)) (Fig. 7A, top). Both hypoxia and TGF-β1 caused a severe down-regulation of E-cadherin, a classical feature of cells that have undergone an EMT. As expected, only hypoxia increased nuclear HIF-1α (hypoxia inducible factor-1α) levels (Fig. 7A, top). Interestingly, TGF-β1-induced up-regulation of SNAIL1 protein correlated with a substantial increase in Snail1 mRNA, a change that was not observed under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 7A, bottom). Therefore, increased expression of SNAIL1 in hypoxia was not a consequence of increased SNAIL1 transcription. Similar results were obtained in MCF-7 cells; hypoxia increased both endogenous SNAIL1 protein levels (Fig. 7A, top) without altering SNAIL1 mRNA levels (Fig. 7A, bottom).

FIGURE 7.

Hypoxia down-regulates FBXL14 mRNA and stabilizes SNAIL1 protein. A, NMuMG (left) and MCF-7 (right) cells were cultured under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions for 72 h or in normoxic conditions with TGF-β1 for the same length of time. The levels of the indicated proteins were determined by Western blot (WB) using total cell extracts (SNAIL1, E-cadherin, and pyruvate kinase (PyrK)) or nuclear cell extracts (HIF-1α). Increase in HIF-1α and down-regulation of E-cadherin proteins were determined as markers of hypoxia and EMT, respectively. mRNA levels of SNAIL1, FBXL14, and HPRT were assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR (see specific conditions in the supplemental material). Notice the down-regulation of FBXL14 mRNA under hypoxia that occurs in parallel with the up-regulation of SNAIL1 protein but not mRNA. Figure panels are representative of three independent experiments with very similar results. B, NMuMG (left) and MCF-7 (right) cells were transfected with SNAIL1-HA, FBXL14-Myc, and GFP as control and cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Relative levels of exogenous SNAIL1-HA were determined by Western blot and compared with those of GFP used to normalize transfection (upper panels). In the lower panel, the blots corresponding to three different experiments were scanned, and the relative values of SNAIL1-HA protein obtained under hypoxic conditions were represented versus those obtained in normoxia. As above, GFP levels were used to normalize the efficiency of transfection. The experiments were carried out using NMuMG (left) and MCF-7 (right) cells. The figure shows the average ± S.D. of the densitometric analyses of three independent experiments.

To check whether SNAIL1 protein stability was altered during hypoxia, NMuMG cells were co-transfected with a SNAIL1-HA expression plasmid, and the transfectants were subjected to hypoxia. A GFP expression plasmid was transfected as control. Western blot analysis indicated that SNAIL1 ectopic protein was expressed at higher levels in NMuMG cells under hypoxic than under normoxic conditions (Fig. 7B, top, compare lanes 2 and 4), suggesting that SNAIL1 protein is stabilized in these conditions. Quantification of different experiments indicated that expression of ectopic SNAIL1 was increased by 2.5-fold with respect to the GFP internal control (Fig. 7B, bottom). Similar results were obtained in MCF-7 cells; hypoxia also increased exogenous SNAIL1 protein levels (Fig. 7B).

Because SNAIL1 protein stability was increased in hypoxia, we analyzed the levels of FBXL14 in these conditions. As shown in Fig. 7A, the mRNA levels of FBXL14 were importantly down-regulated at low O2 concentrations in both NMuMG and MCF-7 cell lines. On the contrary, they were not significantly modified by TGF-β1 treatment. These data suggest that hypoxia increases SNAIL1 protein stability through, at least partially, the down-regulation of FBXL14. Accordingly, co-transfection of FBXL14 impaired the ectopic SNAIL1 stabilization caused by hypoxia in both NMuMG and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 7B, top, compare lanes 3 and 4), further indicating that the reinstatement of FBXL14 levels stimulates SNAIL1 degradation.

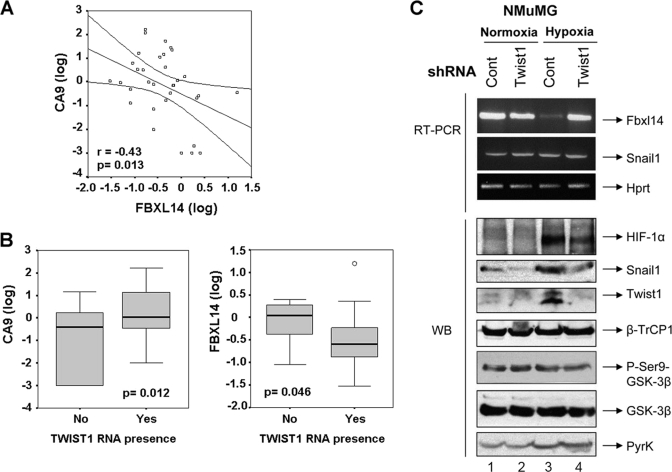

FBXL14 Is Down-regulated in Human Tumors Undergoing Hypoxia and Is Associated with TWIST1 Expression

We also analyzed whether FBXL14 down-regulation was detected in pathological conditions of hypoxia. For this goal, we determined the expression of FBXL14 and CA9 (carbonic anhydrase 9), a marker of hypoxia (22), in a set of 33 human colon adenocarcinomas. CA9 RNA was not detected in normal colon mucosa but was observed in 30 tumor samples (see supplemental material). Conversely, FBXL14 RNA was decreased in 25 tumor samples with respect to normal tissues. A statistical inverse correlation was observed between the expression of FBXL14 and CA9 (r = 0.43; p = 0.013) (Fig. 8A). We also analyzed the expression of TWIST1, a transcription factor involved in triggering EMT (23), that is up-regulated during hypoxia (4). A correlation was also observed when the expression of this transcription factor was categorized, between the presence of TWIST1 and the down-regulation of FBXL14 (geometric average 0.3 in TWIST1-positive cases versus 0.81 in negative TWIST1 samples, p = 0.046, analysis of variance) (Fig. 8B). Expression of TWIST1 also correlated with the up-regulation of CA9 (geometric average 1.83 in cases with TWIST1 presence versus 0.09 when TWIST1 was not detected, p = 0.012, analysis of variance) (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of FBXL14 mRNA is associated with TWIST1 expression. A, expression of CA9 and FBXL14 show an inverse correlation in human tumors. The expression of the different transcripts was performed by quantitative RT-PCR as indicated in the supplemental material. The results corresponding to FBXL14 and CA9 expression are shown, indicating the Pearson correlation coefficient. B, the box plots show the relationships between presence or absence of TWIST1 in tumor tissues and CA9 RNA levels (left) or FBXL14 RNA levels (right). Details of the statistical analysis are also provided in the supplemental material. C, stable inhibition of TWIST1 by shRNA infection interferes with hypoxia-induced FBXL14 down-regulation. NMuMG cells were infected with control or Twist1 shRNAs and cultured under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions. mRNA and protein levels were determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR (top) and Western blot (bottom). HIF-1α protein levels were used as a control of hypoxia.

Because TWIST1 and FBXL14 expression were inversely related, we hypothesized that an increase in TWIST1 was required for Fbxl14 down-modulation and SNAIL1 stabilization during hypoxia of NMuMG cells. As shown in Fig. 8C, infection of Twist1 shRNAs in NMuMG cells prevented TWIST1 up-regulation in hypoxic cells (compare lanes 3 and 4). Twist1 shRNA also inhibited SNAIL1 protein increase without affecting Snail1 mRNA (Fig. 8C). Concomitantly, Twist1 inhibition precluded the decrease in Fbxl14 mRNA caused by hypoxia (Fig. 8C, compare lanes 3 and 4). We also determined if hypoxia or TWIST1 were affecting β-TrCP1/GSK-3β activity. The levels of β-TrCP1 were not decreased by hypoxia in NMuMG cells (Fig. 8C, compare lanes 1 and 3). Phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser-9, indicative of inactivation of this enzyme, was not increased, suggesting that stabilization of SNAIL1 protein in NMuMG cells is not a consequence of decreased activity of GSK-3β. GSK-3β Ser-9 phosphorylation was not observed either in MCF-7 cells under hypoxia (not shown). These experiments suggest that TWIST1 stimulation during hypoxia is necessary to down-regulate FBXL14 and to stabilize SNAIL1 protein levels independently of β-TrCP1/GSK-3β.

DISCUSSION

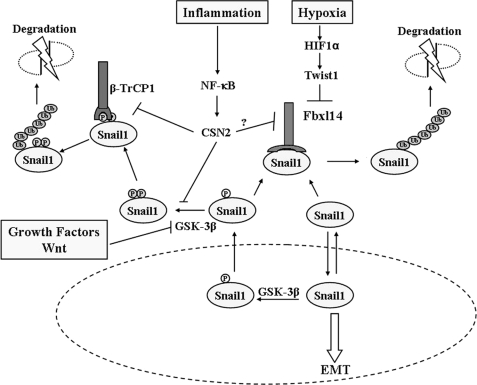

It has previously been shown that SNAIL1 degradation by the proteasome depends on the activity of the E3 ligase complex SCF-FBXW1/β-TrCP1 (9). As depicted in Fig. 9, SNAIL1 ubiquitylation by this E3 ligase needs the activity of GSK-3β to phosphorylate serine residues in the degradation motif placed in the SRD. A previous phosphorylation in adjacent sites by the same protein kinase is required for the export of the protein from the nucleus (Fig. 9). In this work, we demonstrate that SNAIL1 protein stability is dynamically regulated in different cell lines by a GSK-3β/β-TrCP1-independent process. This regulation requires the activity of FBXL14, which promotes SNAIL1 ubiquitylation and proteasome degradation (Fig. 9). The physiological relevance of these findings is further supported in the model of hypoxia, where SNAIL1 protein stabilization occurs in parallel with endogenous FBXL14 mRNA down-regulation.

FIGURE 9.

SNAIL1 protein stability is controlled by two ubiquitin ligases regulated by different stimuli. The presence of SNAIL1 in the nucleus is required for the induction of EMT. Upon phosphorylation by GSK-3β, SNAIL1 is actively exported to the cytosol. Alternatively, SNAIL1 can also translocate to the nucleus by passive diffusion. In the cytosol, SNAIL1 can be further phosphorylated by GSK-3β and bound by β-TrCP1 ubiquitin ligases, ubiquitylated, and targeted for degradation by the proteasome. Alternatively, either the phosphorylated or the unphosphorylated forms of the protein can associate with FBXL14 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in SNAIL1 degradation. Signals from extracellular growth factors and Wnt result in SNAIL1 stabilization because they inhibit GSK-3β activity, blocking SNAIL1 phosphorylation, nuclear export, and ubiquitylation by β-TrCP1. Moreover, during inflammation, cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, stimulate NF-κB signaling, increasing CNS2, which inactivates β-TrCP1, either by preventing SNAIL1 phosphorylation by GSK-3β or preventing SNAIL1 interaction with β-TrCP1. It remains to be determined whether CNS2 also prevents FBXL14 association with SNAIL1 and further degradation. Hypoxia increases SNAIL1 protein stability through a different mechanism that requires activation of HIF-1α and TWIST1 and FBXL14 down-regulation.

The FBXL14 orthologue Ppa has been reported to interact with Snail2 in Xenopus, specifically with a hydrophobic region of Snail2 located at the N terminus, between amino acids 38 and 64 (14). Our data with SNAIL1 N-terminal deletion mutants further indicate that the N-terminal domain of SNAIL1 is also important for FBXL14-mediated degradation. However, a perfect correlation between the SNAIL2 and SNAIL1 sequences does not exist, because the SNAIL1-sensitive sequence is located between amino acids 120 and 151. Part of this sequence is hydrophobic, specifically the region comprising amino acids 125–137, similar to the sequence described to be involved in Ppa-dependent degradation of Snail2. Therefore, it is possible that binding to Ppa/FBXL14 is a consequence of the conservation of a structural, more than linear, motif.

SNAIL1 protein stability is also stimulated by its interaction with the LOXL2 protein, although the mechanism that causes this stabilization remains unknown (24). Interestingly, LOXL2 interacts with the N-terminal part of SNAIL1, and stabilization might occur by interfering with FBXL14 or β-TrCP1 binding to SNAIL1 protein. A similar mechanism of stabilization has been recently reported for CSN2 (COP9 signalosome 2), a protein induced upon NF-κB activation during inflammation (25). CSN2 expression stabilizes SNAIL1 and increases the non-phosphorylated form of this protein (Fig. 9). According to the authors, this effect might be due to the inhibition of GSK-3β or to β-TrCP1 binding to SNAIL1; however, an alternative and more plausible possibility is that CSN2 prevents the association of FBXL14 with SNAIL1 (Fig. 9).

Another point of discussion is the cellular location where the interaction of FBXL14 and SNAIL1 takes place. Our immunofluorescence data in NIH3T3 (Fig. 3) and RWP-1 cells (not shown) indicate that FBXL14 is predominantly cytoplasmic. Therefore, because it occurs with β-TrCP1, the interaction of SNAIL1 and FBXL14 probably takes place in this compartment (9). The fact that FBXL14 interacts with both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated SNAIL1 increases the likelihood that this E3 ubiquitin ligase down-regulates SNAIL1 levels before its translocation to the nucleus. Alternatively, it may also degrade SNAIL1 protein that is being exported from the nucleus, either actively after phosphorylation or passively by diffusion (Fig. 9).

Tumor progression has been associated with hypoxia (i.e. decreased oxygen levels within the primary tumor) (26). Intratumoral hypoxia is a mechanism of adaptative tumor survival promoting cell proliferation, drug resistance, increased cell migration, and invasion. The acquisition of a more mesenchymal phenotype is frequently associated with hypoxia and is related to the expression of several transcription factors, such as HIF-1α and TWIST1 (27). Activation of TWIST1 but not SNAIL1 mRNA has also been detected in cells during hypoxia (4) due to the direct binding of HIF-1α to the TWIST1 promoter. In this report, we demonstrate that SNAIL1 protein is induced during hypoxia. This increase is dependent on the up-regulated stability of the protein and is associated with a selective down-regulation of FBXL14, a process regulated by TWIST1 (Fig. 9). This post-translational effect of hypoxia on the expression of SNAIL1 might be related to the severe stress that this insult causes, which produces a general inhibition of translation (28). Accordingly, the up-regulation of SNAIL1 should be promoted by a mechanism capable of bypassing this block.

Apart from HIF-1α and Twist1, several other factors involved in EMT have been described to be activated during hypoxia. For instance, activation of the NOTCH signaling pathway has been reported (29). According to these authors, the NOTCH intracellular domain activates the transcription of the SNAIL1 gene. For these authors, hypoxia also raises LOX mRNA levels. It is still unclear whether LOX behaves similarly to LOXL2 and stabilizes SNAIL1 protein levels. In any case, it is possible that the higher stability of SNAIL1 during hypoxia is a consequence of both the down-modulation of FBXL14 and the up-regulation of LOX.

Our results add a new level of complexity to the regulation of SNAIL1 protein stability. β-TrCP1-dependent degradation of SNAIL1 has been shown to be tightly regulated because the activity of GSK-3β can be down-modulated by Wnt ligands (13). Moreover, the Wnt target gene AXIN2 indirectly increases SNAIL1 stability by redirecting nuclear GSK-3β to the cytoplasm and preventing SNAIL1 active export (30). All together, these results suggest that SNAIL1 protein stability is finely regulated by conditions as different as the action of growth factors (acting on GSK-3β/β-TrCP1), hypoxia (on FBXL14), or inflammation (probably acting through both ubiquitin ligases) (see Fig. 9 for a summary). This complex regulation is probably a consequence of the essential role of this factor in triggering EMT and apoptosis resistance and of the lower stability of the protein. Thus, increased SNAIL1 protein half-life, either accompanied by up-regulated transcription or not, would be essential for the enhanced SNAIL1 function required for EMT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

pMT107 containing human ubiquitin (His6) was kindly given by Dr. Gabriel Gil-Gómez (Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona). His-Ubiquitin-K7R plasmid was provided by Dr. Boudewijn M. T. Burgerin (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands). pCDNA-FLAG-βTrCP1/ TrCP2 was kindly provided by Dr. Ger Strous (University Medical Center Utrecht). We thank Drs. Timothy Thomson (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Barcelona) and Lluis Espinosa (Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona) for reagents and advice.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología Grant SAF2006-00339 and by a grant from the Fundació La Marató de TV3 (to A. G. H.). This work was also supported in part by Instituto Carlos III Grants RD06/0020/0040 and RD06/0020/0020 and by Generalitat de Catalunya Grant 2005SGR00970.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1.

- EMT

- epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- SRD

- serine-rich domain

- NES

- nuclear export sequence

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- RT

- reverse transcription

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- WT

- wild type

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- shscrbl

- scrambled shRNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thiery J. P., Sleeman J. P. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boutet A., De Frutos C. A., Maxwell P. H., Mayol M. J., Romero J., Nieto M. A. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 5603–5613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang M. H., Wu M. Z., Chiou S. H., Chen P. M., Chang S. Y., Liu C. J., Teng S. C., Wu K. J. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batlle E., Sancho E., Francí C., Domínguez D., Monfar M., Baulida J., García De Herreros A. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vega S., Morales A. V., Ocaña O. H., Valdés F., Fabregat I., Nieto M. A. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 1131–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escrivà M., Peiró S., Herranz N., Villagrasa P., Dave N., Montserrat-Sentís B., Murray S. A., Francí C., Gridley T., Virtanen I., García de Herreros A. (2008) Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 1528–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kajita M., McClinic K. N., Wade P. A. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 7559–7566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou B. P., Deng J., Xia W., Xu J., Li Y. M., Gunduz M., Hung M. C. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart M., Concordet J. P., Lassot I., Albert I., del los Santos R., Durand H., Perret C., Rubinfeld B., Margottin F., Benarous R., Polakis P. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frescas D., Pagano M. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 438–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domínguez D., Montserrat-Sentís B., Virgós-Soler A., Guaita S., Grueso J., Porta M., Puig I., Baulida J., Francí C., García de Herreros A. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 5078–5089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yook J. I., Li X. Y., Ota I., Fearon E. R., Weiss S. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11740–11748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernon A. E., LaBonne C. (2006) Development 133, 3359–3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francí C., Takkunen M., Dave N., Alameda F., Gómez S., Rodríguez R., Escrivà M., Montserrat-Sentís B., Baró T., Garrido M., Bonilla F., Virtanen I., García de Herreros A. (2006) Oncogene 25, 5134–5144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan B., Latek R., Hossbach M., Tuschl T., Lewitter F. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W130–W134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ougolkov A., Zhang B., Yamashita K., Bilim V., Mai M., Fuchs S. Y., Minamoto T. (2004) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96, 1161–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardozo T., Pagano M. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M., Brooks C. L., Wu-Baer F., Chen D., Baer R., Gu W. (2003) Science 302, 1972–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peinado H., Quintanilla M., Cano A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21113–21123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirakihara T., Saitoh M., Miyazono K. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 3533–3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wykoff C. C., Beasley N. J., Watson P. H., Turner K. J., Pastorek J., Sibtain A., Wilson G. D., Turley H., Talks K. L., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Harris A. L. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 7075–7083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J., Mani S. A., Donaher J. L., Ramaswamy S., Itzykson R. A., Come C., Savagner P., Gitelman I., Richardson A., Weinberg R. A. (2004) Cell 117, 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peinado H., Del Carmen Iglesias-de la Cruz M., Olmeda D., Csiszar K., Fong K. S., Vega S., Nieto M. A., Cano A., Portillo F. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 3446–3458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Y., Deng J., Rychahou P. G., Qiu S., Evers B. M., Zhou B. P. (2009) Cancer Cell 15, 416–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouysségur J., Dayan F., Mazure N. M. (2006) Nature 441, 437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peinado H., Cano A. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 253–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L., Cash T. P., Jones R. G., Keith B., Thompson C. B., Simon M. C. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahlgren C., Gustafsson M. V., Jin S., Poellinger L., Lendahl U. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6392–6397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yook J. I., Li X. Y., Ota I., Hu C., Kim H. S., Kim N. H., Cha S. Y., Ryu J. K., Choi Y. J., Kim J., Fearon E. R., Weiss S. J. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1398–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.