Abstract

Macrophage proliferation can be stimulated by phagocytosis and by cross-linking of Fcγ receptors (FcγR). In this study, we investigated the role of FcγR and the signaling cascades that link FcγR activation to cell cycle progression. This effect was mediated by the activating FcγR, including FcγRI and III, via their Fcγ subunit. Further investigation revealed that the cell cycle machinery was activated by FcγR cross-linking through downstream signaling events. Specifically, we identified the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway as a mediator of signals from FcγR activation to cyclin D1 expression, because cyclin D1 expression associated with FcγR cross-linking was attenuated by specific inhibitors of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, PD98059 and U0126 and the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor, Piceatannol. Our findings establish a link between the ERK activation and cell cycle signaling pathways, thus providing a causal mechanism by which FcγR activation produces a mitogenic effect that stimulates macrophage proliferation. Macrophage mitosis following FcγR activation could potentially affect the outcome of macrophage interactions with intracellular pathogens. In addition, our results suggest the possibility of new treatment options for certain infectious diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, and leukemias based on interference with FcγR-stimulated macrophage cell proliferation.

Keywords: Cell/Division, Immunology/Innate Immunity, Receptors/Leukocyte/Lymphocyte, Signal Transduction/G-proteins, Antibodies, Immunology, ERK, Macrophage

Introduction

Macrophages are cells of the innate immune system that constitute the first line of defense against many infectious diseases. As one of the professional phagocytic cells in the host, they function in promoting the clearance of invading microorganisms by phagocytosis and digestion. Furthermore, activated macrophages are also important cells in orchestrating adaptive immune responses by releasing various inflammatory cytokines as well as presenting antigen to T cells. Activation of membrane Fc receptors (FcR)4 on macrophages is critical in triggering antibody-mediated effects. FcR, which recognizes the immunoglobulin Fc domain, bridges two major host defense mechanisms, innate immunity and adaptive immunity, through Fc-mediated phagocytosis (1). As the first step of Fc-mediated phagocytosis, antibodies opsonize microbes, which can then cross-link FcR on the cell membrane. FcR cross-linking triggers complicated signaling transduction pathways that promote phagocytosis and induces the transcription of numerous genes in macrophages that contribute to subsequent inflammatory and immune responses.

Given the central role of macrophage FcR activation in host cellular immunity, the signaling cascades resulting from FcR activation on macrophages have been extensively studied over the past two decades. Briefly, antibody-opsonized particles cross-link FcR on macrophage cell surface and trigger downstream signals, which start with the phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) on the intracellular domain of FcR by Src tyrosine kinases. The phosphorylated ITAMs recruit and activate Syk tyrosine kinase (2–4). The activation of Src and Syk play important roles in many aspects of macrophage functions including Fc-mediated phagocytosis and other immune regulation processes in macrophages. Many signaling molecules are activated downstream of Syk and Src in Fc-mediated phagocytosis including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), small GTPases (Rho, CDC42), and phospholipase C. The activation of these signals ultimately results in cytoskeleton changes and membrane ruffling during the phagocytic process (5–7).

FcR cross-linking during phagocytosis also activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (8–11). The MAPK family includes ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). They play significant roles in mediating signals triggered by cytokines, growth factors and stress (12). The role of MAPK signaling pathway in the particle ingestion process is still controversial (13). Nevertheless MAPK activation is required by Fc-mediated activation of the nuclear factor NFκB, which regulates the transcription of many genes expressed during inflammatory responses following phagocytosis of microbes (14–18). In addition, ERK was shown to be downstream of Syk activation during phagocytosis of Francisella tularensis (19).

The mammalian cell cycle is divided into G1, S, G2, and M phases. The regulation of this cycle is primarily controlled by periodic synthesis and destruction/activation of cyclins, which in turn bind to, and activate cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). Cyclin D expression is induced by external mitogenic stimuli to cells. It functions as the connection of cell cycle machinery to outside signaling by phosphorylating the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor family of proteins through the binding of cyclin D with CDK4 and CDK6. Phosphorylation of Rb prevents binding to E2F factors and thus switches E2F from a repressor to an activator of gene expression of cell cycle proteins, including cyclin E and cyclin A. Cyclins E and A then participate in a positive feedback control by maintaining Rb in hyper-phosphorylated state and thus drives the cell cycle passes the restriction point in late G1 phase and goes through S and G2 (20). Multiple regulatory mechanisms of cell cycle progress exist. For example, p21 is a potent CDK inhibitor, which binds to, and inhibits the activity of cyclin-CDK2 or -CDK4 complexes, and thus functions as a regulator of cell proliferation at G1. Historically, macrophages have played a significant role in the discovery of the mechanism of mammalian cell cycle control (21). Cyclin D1 and CDK4, two key components of G1 phase control were first discovered in murine macrophages stimulated with colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) (22, 23). Despite the contribution of macrophages to our understanding of cell cycle control, the relationship between FcR activation and cell division has not been explored, possibly because macrophages were considered postmitotic cells, until recently. However, several studies have now shown that macrophages in local tissue can undergo mitosis, especially in the presence of inflammatory conditions (24–37).

Previously we reported that macrophage cell division can be stimulated by Fcγ receptors (FcγR) activation either during phagocytosis or by IgG1-coated cell culture plates, and that a similar effect could be observed with peritoneal macrophage populations in vivo (38). In the present study, we further documented FcγR cross-lining by IgG antibodies leads to the activation of cell cycle machinery in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) and peritoneal macrophages (PM). We also demonstrated that this effect was mediated by the activating FcγR including FcγRI and III via their Fcγ subunit and sequential activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Given that many growth factors use similar signaling pathways to induce cell proliferation (12), our results imply that activation of FcγR on macrophages could exert a mitogenic effect similar to the stimulation of growth factors and consequently stimulate macrophage cell proliferation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

ERK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). PD98059 and U0126 bind to MEK and prevent further phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (p44/p42 MAPK) by MEK (39, 40). p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and Syk inhibitor Piceatannol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. JNK inhibitor SP600125 was obtained from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) was obtained as CellTraceTM CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). Colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) used for cell culture was obtained from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Antibodies for Western Blots

The primary antibodies for the Western blots of cyclin D1 (H-295), cyclin E (M-20), cyclin A (C-19), CDK2 (H-298), CDK4 (C-22), p21 (F-5), and Rb (C-15) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The primary antibody for the Western blots of pRb (Ser807/811), ERK1/2 (p44/42 MAPK), and pERK1/2 (phospho-p44/42 MAPK) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. The primary antibody for β-tubulin was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (NA 934V) and mouse (NA 931V) antibodies were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). The primary and secondary antibodies were used at the manufacturer-recommended dilutions for Western blot.

Culture of Murine Macrophages

For wild-type BMM, 3-month-old male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). FcγRI−/−, FcγRII−/−, FcγRIII−/−, and Fcγ−/− mice, which were generated from C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the animal facility at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Bronx, NY). Mice were euthanized, and bone marrow cells were harvested from the hind leg bones. Erythroid cells were lysed with 1× ammonium chloride lysing solution. (10× ammonium chloride lysing solution was made with 1.5 m NH4Cl, 100 nm KHCO3, 10 nm Na4EDTA, and distilled H2O. The pH was adjusted to 7.4. 10× stock solution should be stored at 4 °C no longer than 6 months. The 1× working solution was prepared fresh daily with distilled H2O.) Bone marrow cells containing monocytes were cultured at 37 °C with 10% CO2 in DME medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Both IL-3 and CSF-1 were added to the medium for the first week. On the second week, CSF-1 was added alone. The medium was replaced every 3 days to remove floating B cells. After 2 weeks of culture, BMM were ready for experimental use. PM were obtained from 3-month-old male C57BL/6 mice by peritoneal lavage with sterile PBS. The harvested cells were cultured at 37 °C with 10% CO2 in DME medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and CSF-1. The medium was replaced after 3 days to remove floating cells. The PM attached to the plates were ready for experimental use. The classic method for preparing BMM with CSF-1 stimulation used for this study gives 99% purity of F4/80 CD11b-positive macrophages. They are mature by most markers but not activated. Class 11 positive macrophages are phagocytic. In terms of PM, our method should also give highly enriched population of macrophages, which are more activated compared with those from BMM cultures.

CFSE Staining of Macrophages for FcγR Cross-linking Assay and Cell Cycle Analysis

A 5 mm CFSE stock solution was prepared immediately prior to use by dissolving one vial of CFSE with 18 μl of DMSO provided in the kit. Macrophage cells in culture were harvested by gently scraping. To stain 107 cells, 1 ml of working solution of 10 μm CFSE was diluted with 2 μl of 5 mm CFSE stock into 1 ml PBS/0.1% BSA. 107 cells were suspended and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. CFSE staining was then quenched by adding 5 ml of ice-cold DME culture medium and incubated on ice for 5 min. The cells were centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were washed with DME culture medium for three times. The CFSE-stained macrophage cells were ready for FcγR cross-linking assay and cell proliferation analysis.

FcγR Cross-linking Assay

Coating antibodies coated on immobile surface was commonly used to cross-link FcR on macrophage cell membrane, and this process was also called frustrated phagocytosis (41–43). The similar method was used in the FcγR cross-linking assay. To prepare the culture plates for the cross-linking assay, IgG1 monoclonal antibody 18B7 (44) or IgG2a mAb 3E5 (45) was diluted with PBS to 20 μg/ml, which was previously ascertained as the optimal concentration for the assay (38). Diluted IgG1 or IgG2a or BSA at same concentration as negative control were added at a volume of 1 ml per well into 6-well plates to cover the bottom of wells. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h or 4 °C overnight. Before the cross-linking assay, macrophages were deprived of CSF-1 from the medium for 2 days, and the macrophages were synchronized in the G1 phase of cell cycle. 1 × 106 macrophage cells in 2 ml of DME medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum per well were seeded into the coated culture plates for cross-linking assay. The macrophage cells were stained with CFSE prior to FcγR cross-linking assay for cell proliferation analysis whereas for Western blots or cell cycle analysis the cells were not stained. The macrophage cells were incubated on coated plates at 37 °C with 10% CO2 for indicated time up to 11 h. Longer time points were not selected due to the fast response of cell proliferation to the stimulation of FcγR cross-linking, to avoid the possibility of autocrine effects complicating results and to reduce the risk for apoptosis after deprivation of CSF-1 for 2 days. Monolayer cells were harvested for cell proliferation analysis, cell cycle analysis, or Western blots.

Cell Proliferation Analysis with Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

After the FcγR cross-linking assay, macrophage monolayer cells were stripped off the bottom of culture plates by Cellstripper solution (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) from the 6-well plates and suspended in 400 μl of PBS/1% PFA for each well for fixation. The fixed cells were then analyzed on a BD LSR II flow cytometer with 488 nm excitation (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). FACS data were analyzed using the cell proliferation platform in Flowjo 8.8.6 software (Ashland, OR) for cell proliferation analysis. The cell proliferation rate was quantified by the Percentage of Division (% Division).

Cell Cycle Analysis with FACS

After FcγR cross-linking assay, macrophage monolayer cells were stripped off the bottom of culture plates by Cellstripper solution from the 6-well plates. Cells were fixed by the addition of 5 ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol, and a 2-h incubation on ice. In preparation for FACS analysis, cells were centrifuged at 600 rpm for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended, and DNA content was labeled by a 0.5-ml solution of propidium iodide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 20 μg/ml in PBS, containing RNase at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. Samples were stained at room temperature for 30 min and analyzed on a FACScan (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Data were analyzed by ModFit 3.0 software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME) for cell cycle distribution. Cell cycle distribution was shown as G1, S, and G2 percentages.

Western Blot

Western blot (immunoblot) analysis was used to detect changes in expression of proteins involved in macrophage proliferation after FcγR cross-linking assay. The macrophage monolayers were washed three times with PBS after FcγR cross-linking assay described above. The resulting monolayer cells were stripped off the bottom of culture plates that were on ice by Cellstripper solution and lysed with ELB buffer (1 m pH 7.0 HEPES, 5 m NaCl, 10% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 m EDTA) by incubating on ice for 30 min. Cellular proteins were quantified using the BCA protein assay reagent kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of whole cell lysates, as normalized for protein content, were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). Membranes were probed with antibodies at recommended dilutions in 5% milk in TBST (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.5) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or mouse IgG antibody (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at a 1:5000 dilution in 5% milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Protein blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) for 3 min and subjected to exposure on autoradiography films (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ).

Immunoprecipitation and in Vitro Kinase Assay

Macrophage monolayer cells were stimulated by FcγR cross-linking and harvested as described above. Immunoprecipitation and in vitro CDK4 kinase assays were performed as described by Chen and Pollard (46). The macrophage monolayer cells were lysed by incubation of cells in extraction buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH at pH 7.5, 0.1 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mm NaF, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, and 10 μg of pepstatin A/ml). An equal amount of the washing buffer (90 mm HEPES-KOH at pH 7.5, 0.2 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 0.2% Tween 20, 10% glycerol, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm NaF, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, and 10 μg of pepstatin A/ml) was added. The resultant lysates were incubated with 1 μg of cyclin D1 antibody for 1 h on ice. The immunocomplexes were collected by incubation with protein G beads overnight at 4 °C with shaking. The immunoprecipitates were then used for Rb kinase assay. The kinase reaction was started by the addition of 30 μl of kinase buffer (50 mm HEPES-KOH at pH 7.5, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 2.5 mm EGTA, 10 mm glycerophosphate, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, and 1 mm NaF), 20 μm ATP, truncated Rb protein (p56Rb; amino acids 379–928; QED Bioscience, San Diego, CA), and 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP. The kinase reaction was performed at room temperature for 1 h and then stopped by adding loading buffer and boiling to denature.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare %Division in a cell proliferation analysis of macrophages. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was done by GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Cell Proliferation of Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages and Peritoneal Macrophages Is Activated by FcγR Cross-linking

Previously we reported activation of cell proliferation of J774.16 macrophage-like cells, BMM, and PM after phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans or inert polystyrene beads (38). Phagocytosis is an extremely complicated process involving membrane rearrangement, and the activation of multiple signaling pathways are involved (7). Consequently, we sought a simplified the experimental system where we could separate the effects of FcγR from any downstream signaling effects that could follow particle ingestion. Fortunately, we had shown in our previous study, that J774.16 macrophage-like cells manifested cell proliferation in the FcγR cross-linking assay by which the cells were incubated on a tissue culture plate coated with the monoclonal IgG1 antibody 18B7 (38). Therefore, in the current study we used the FcγR cross-linking assay to explore the mechanisms involved in the macrophage cell proliferation instead of phagocytosis. In addition, BMM and PM were used to avoid ambiguities that would be associated with cell lines. BMM and PM stimulated by FcγR cross-linking assay proliferate in a manner similar to that observed with J774.16 macrophage-like cells as described in our previous study (Figs. 1 and 2).

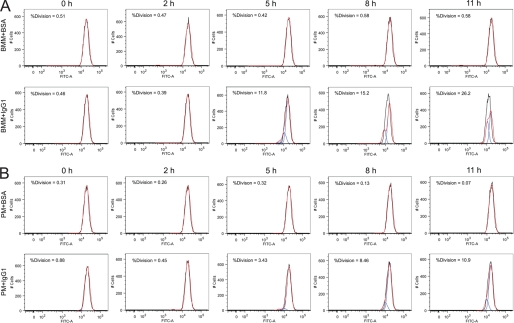

FIGURE 1.

Cell proliferation of BMM and PM after FcγR cross-linking. Cell proliferation analysis of BMM (A) and PM (B) after FcγR cross-linking assay with IgG1-coated culture plates (BMM+IgG1 and PM+IgG1) relative to BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BMM+BSA and PM+BSA). Prior to the assay, BMM or PM were stained with CFSE and then seeded on BSA- or IgG1-coated culture plates. After collection and fixation, the cells were subjected to FACS analysis for intensity of CFSE signals determined by FITC-Area (FITC-A). The FACS sata were then processed using the cell proliferation platform in Flowjo software. In each panel, the black line peak is the actual histogram of CFSE signal, which represents the primary data we collected in our experiments. Red line peak indicated the mold sum and blue line peak indicated model components in the proliferation analysis. %Division calculated according to model components are labeled on the left upper corner of each panel. The representative flow data of an experiment are shown in this figure. The experiment was independently repeated three times and produced similar results. The data of three repeats and the statistical analysis are shown in Fig. 2.

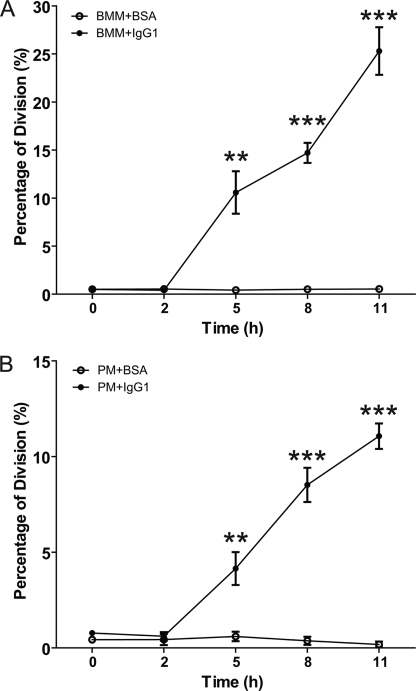

FIGURE 2.

%Division calculated by cell proliferation analysis of BMM and PM after FcγR cross-linking. The %Division calculated by cell proliferation analysis of BMM (A) and PM (B) after FcγR cross-linking assay with IgG1-coated culture plates (BMM+IgG1 and PM+IgG1) relative to BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BMM+BSA and PM+BSA). Differences in %Division between BMM+BSA and BMM+IgG1 were analyzed by Student's t test, and those at 5, 8, and 11 h were statistically significant with **, p < 0.001 and ***, p < 0.0001. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

Before the FcγR cross-linking assay was carried out, macrophages were deprived of CSF-1 for 2 days to synchronize the cells in the G1 phase of cell cycle. Macrophages were then stained with CFSE dye before seeding on the plates coated with either IgG1 mAb 18B7 or BSA (negative control). The cells were incubated and harvested after 0, 2, 5, 8, and 11 h. The CFSE staining intensity of the cells was measured by FACS to detect the cell proliferation of macrophages. Because cell division leads to diminished CFSE staining, this method establishes the completion of mitosis after cell cycle progression. The collected FACS data were further analyzed using the cell proliferation platform within the Flowjo software and %Division calculated. Cell proliferation of BMM (Fig. 1A) and PM (Fig. 1B) was first detected 5 h after the cells were seeded on the IgG1-coated culture plates (BMM+IgG1 and PM+IgG1). In contrast, no proliferation was apparent in the control conditions (BMM+BSA and PM+BSA) up to 11 h of observation. A difference in %Division was observed between BMM and PM (Fig. 2). For BMM, the %Division was increased to ∼10% at 5 h and reached between 25 and 30% by 11 h (Fig. 2A), whereas PM manifested a lower %Division under similar culture systems, that started from less than 5% at 5 h and increased to between 10 and 15% by 11 h (Fig. 2B).

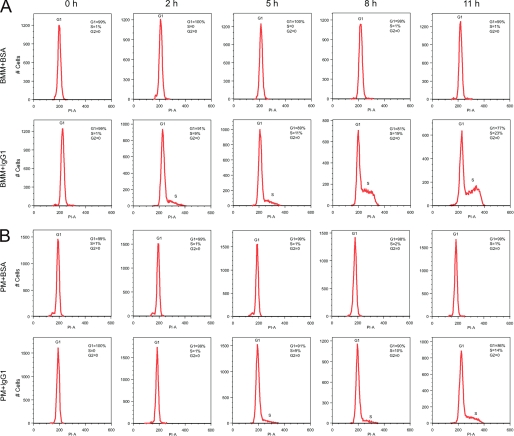

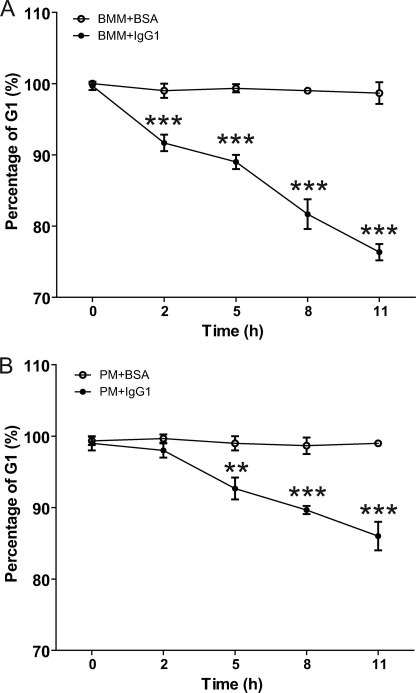

To further confirm our observations with CFSE staining, we carried out cell cycle analysis with PI staining of cells after the cross-linking assay. After the cross-linking assay, macrophages were collected and fixed. DNA content of the fixed macrophages was stained with PI solution, and the cells were subjected to FACS analysis. The collected FACS data were processed using cell cycle platform within Flowjo, and cell cycle distributions of the macrophages were calculated using Modfit software. Consistent with the CFSE results, cell cycle progression of BMM and PM from G1 phase to S phase were detected as early as 2 h after the FcγR cross-linking (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Given that cell proliferation after FcγR cross-linking was observed for both PM and BMM and that the effect with BMM was significantly greater using CFSE staining, we chose BMM and CFSE staining for our further studies on the mechanisms of macrophage cell proliferation.

FIGURE 3.

Cell cycle progression of BMM and PM after FcγR cross-linking. Cell cycle analysis of BMM (A) and PM (B) after FcγR cross-linking assay with IgG1-coated culture plates (BMM+IgG1 and PM+IgG1) relative to BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BMM+BSA and PM+BSA). BMM or PM were seeded on BSA- or IgG1-coated culture plates. After the cross-linking assay, cells were collected and fixed. The DNA content of the cells were stained with PI, and the stained cells were subject to FACS analysis for intensity of PI signals determined by PI-Area (PI-A). The FACS data were then processed using the cell cycle platform in Flowjo software as well as Modfit software. The histogram of PI staining is shown as red lines and plotted using Flowjo software. Cell cycle distributions were analyzed using Modfit software, and the percentage of cells at G1, S, and G2 stage calculated is labeled on the right upper corner of each panel. The representative flow data of an experiment are shown in this figure. The experiment was independently repeated three times and produced similar results. The data from three replicates and the statistical analysis of cells at the G1 stage are shown in Fig. 4.

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of cells at G1 stage calculated by cell cycle analysis of BMM and PM after FcγR cross-linking. The percentage of cells at G1 stage calculated by cell proliferation analysis of BMM (A) and PM (B) after FcγR cross-linking assay with IgG1-coated culture plates (BMM+IgG1 and PM+IgG1) relative to BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BMM+BSA and PM+BSA). Differences in percentage of cells at G1 stage between BMM+BSA and BMM+IgG1 were analyzed by Student's t test, and those at 5, 8, and 11 h were statistically significant with **, p < 0.001 and ***, p < 0.0001. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

Cell Proliferation of BMM Stimulated by FcγR Cross-linking Is Mediated by FcγRI and FcγRIII via Their Fcγ Subunit

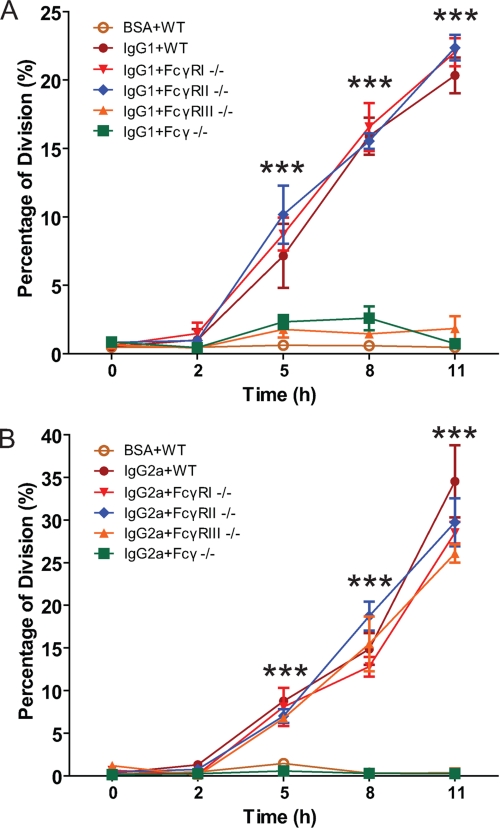

FcγR on murine macrophages include a large family of receptors consisting of the activating receptors (FcγRI and III) and the inhibitory receptors (FcγRII) (47). After cross-linking, the activating FcγR transduce signals through the ITAM located on γ-subunit of the receptors, whereas the inhibitory receptors lack the γ-subunit but have immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM) on their intracellular domains. To differentiate subtype(s) FcγR that stimulate cell proliferation, BMM were obtained from FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, FcγRIII−/−, and Fcγ−/− mice and studied for cell proliferation relative to those from wild-type C57BL/6 mice (WT) in our cross-linking assay. Furthermore, we employed two IgG subclasses in the cross-linking assay, IgG1 and IgG2a. IgG1 binds primarily to FcγRII and III whereas IgG2a binds primarily to FcγRI, II and III (47). Hence, by using BMM from five mouse strains differing in FcγR competency and two IgG isotypes that differ in their ability to activate the different FcγR, we were able to investigate the relative contribution of these receptors to the phenomenon of cell proliferation after FcγR cross-linking (Fig. 5). With IgG1 stimulation, cell proliferation of BMM from FcγRIII−/− and Fcγ−/− mice was minimal compared with that of BMM from WT, FcγRI−/− and FcγRII−/− mice (Fig. 5A). Because IgG1 only binds to FcγRIII, these results indicated that Fcγ subunit was needed for macrophage cell proliferation. With IgG2a stimulation, cell proliferation of BMM from Fcγ−/− mice was minimal compared with that of BMM from WT, FcγRI−/−, FcγRII−/−, and FcγRIII−/− mice (Fig. 5B). Because IgG2a binds to FcγRI, FcγRII, and FcγRIII, these results also indicated that Fcγ subunit was needed for macrophage cell proliferation and suggested that both FcγRI and FcγRIII were involved in this effect. Given that both IgG1 and IgG2a triggered cell proliferation through a process requiring the Fcγ subunit, IgG1 and BMM from WT mice were used in subsequent studies to elucidate the signal transduction events.

FIGURE 5.

%Division calculated by cell proliferation analysis of BMM from FcγR competent and deficient cells after FcγR cross-linking. %Division calculated by cell proliferation analysis of BMM from wild-type C56BL/6, FcγRI−/−, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, FcγRIII−/−, and Fcγ−/− mice after FcγR cross-linking assay with IgG1- (A) or IgG2a-coated culture plates (B) (IgG1+ or IgG2a+WT, FcγRI−/−, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, FcγRIII−/−, and Fcγ−/−, respectively) and BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BSA+WT). Differences in %Division between BSA+WT, IgG1+ or IgG2a+WT, FcγRI−/−, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, FcγRIII−/−, and Fcγ−/− were analyzed by one way ANOVA, and those at 5, 8, and 11 h were statistically significant with ***, p < 0.001. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

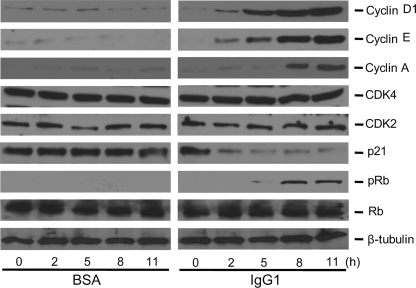

Cell Cycle Machinery of BMM Is Activated by FcγR Cross-linking

The activation of cell cycle machinery in BMM after FcγR cross-linking with IgG1 was documented by probing the levels of several important molecules of mammalian cell cycle control including cyclin D1, cyclin E, cyclin A, CDK2, CDK4, p21, and phosphorylation status of Rb (Fig. 6). Cyclin D1 levels were hardly detectable for 11 h poststimulation in the control group, a condition where macrophages were incubated on BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control. However, when BMM were incubated in IgG1-coated culture plates, cyclin D1 levels consistently increased from 2 h poststimulation with the effect lasting until at least 11 h. The expression levels of cyclin E and cyclin A also increased around 2 and 8 h poststimulation, respectively. CDK2 and CDK4 levels remained stable poststimulation. p21, a cell cycle regulator protein that binds to and inhibits the activity of cyclin-CDK2 or -CDK4 complexes, decreased after 2 h of poststimulation. These results are consistent with the induction of cells into S phase. The phosphorylation of Rb was induced at 8-h poststimulation. This phosphorylation status was maintained until at least 11 h after FcγR cross-linking.

FIGURE 6.

Cell cycle parameters in BMM after FcγR cross-linking. BMM were seeded on IgG1-coated culture plates for an FcγR cross-linking assay (IgG1) with BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control (BSA). Cell contents were extracted after incubation for 0, 2, 5, 8, and 11 h and subjected to Western blotting analysis using antibodies against the protein or its phosphorylated epitope as shown on the right. β-Tubulin staining was used to control for equal loading of each sample. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

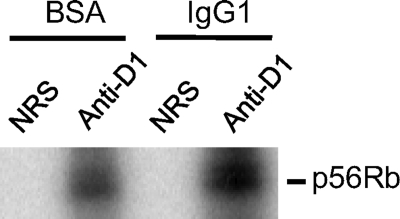

To further establish cyclin D1 as the mediator of FcγR cross-linking-induced Rb phosphorylation, in vitro kinase assay was performed with truncated Rb protein (p56Rb) as the substrate of active form of CDK4/6 (Fig. 7). The complex of cyclin D1 and CDK4/6 complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-cyclin D1 antibody (anti-D1) and non-related serum (NRS) as a control from the cell lysate of macrophage cells stimulated by FcγR cross-linking. Stronger phosphorylation of the truncated Rb substrate in the immune-complex kinase assay was observed for macrophages stimulated with FcγR cross-linking with IgG1 compared with non-stimulated macrophages (BSA). These results established a direct linkage between FcγR cross-linking and activation of cell cycle machinery in macrophages.

FIGURE 7.

In vitro CDK4 kinase assay of BMM after FcγR cross-linking. The cyclin D1-CDK complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-cyclin D1 antibody (anti-D1) from BMM cell extract after FcγR cross-linking assay (IgG1) with BSA-coated culture plates as a negative control for FcγR cross-linking (BSA). Immunoprecipitation with non-related serum (NRS), which did not contain anti-cyclin D1 antibody, was used as the negative control for immunoprecipitation with anti-cyclin D1 antibody. In vitro kinase assay was performed with recombinant p56Rb as the substrate. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

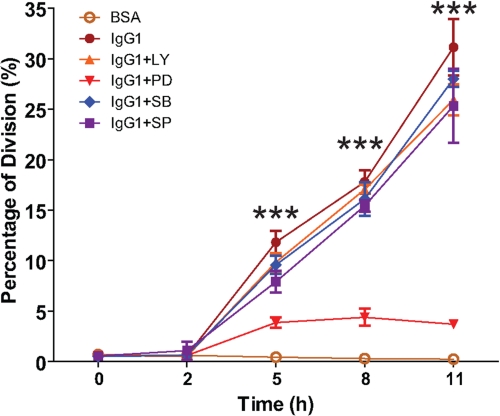

ERK1/2 Activation Is Required for the Activation of Cell Cycle Machinery by FcγR Cross-linking

To identify the signaling pathway responsible for activation of the cell cycle machinery by FcγR cross-linking, specific inhibitors for MAP kinase kinase (MAPKK, also known as MAPK/ERK kinase, MEK) (PD98059), p38 MAPK (SB230580), and PI3K (LY294002) were applied, and cell proliferation of treated BMM was determined by cell proliferation analysis using CFSE staining (Fig. 8). Cell proliferation analysis confirmed cell proliferation of BMM stimulated by FcγR cross-linking as we described previously. The cell proliferation was only attenuated by the MEK inhibitor PD98059, not by p38 MAPK inhibitor SB230580 and PI3K inhibitor LY294002. These results indicated that the activation of ERK pathway might be involved in cell proliferation stimulated by FcγR cross-linking.

FIGURE 8.

%Division of BMM after FcγR cross-linking in the presence and absence of specific ERK, p38 MAPK, and PI3K specific inhibitors. ERK inhibitor (PD98059), p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580), JNK inhibitor (SP600125), and PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) were applied to BMM undergoing FcγR cross-linking by incubation in IgG1-coated plates (IgG1+PD, IgG1+SB, IgG1+SP, and IgG1+LY, respectively). Cells seeded on BSA- (BSA) and IgG1-coated plates (IgG1) were used as the negative and positive control, respectively. The differences in %Division between BMM treated with PD98059 and those treated with SB203580, SP600125, LY294002, and the positive control were analyzed by one way ANOVA, and those at 5, 8, and 11 h were statistically significant with ***, p < 0.0001. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

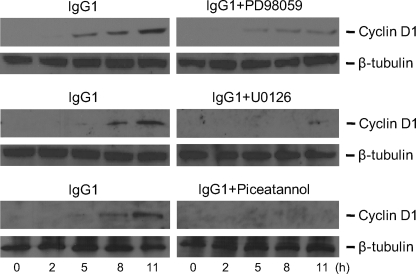

To further elucidate this possibility, MEK inhibitor PD98059 and another specific MEK inhibitor U0126, as well as the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 were applied to BMM stimulated by FcγR cross-linking with IgG1 and cyclin D1 expression levels in treated BMM cell extract were then detected by Western blots. For PD98059- and U0129-treated BMM, FcγR cross-linking was associated with significantly diminished cyclin D1 levels (Fig. 9). Similarly as in cell proliferation analysis, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 did not attenuate the induction of cyclin D1 expression induced by FcγR cross-linking (data not shown). To confirm that the induced cyclin D1 expression was indeed activated by FcγR cross-linking, Piceatannol was used to specifically inhibit spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), which is an important adaptor of FcγR cross-linking-induced downstream signaling (48). Application of Piceatannol aborted cyclin D1 expression induced by FcγR cross-linking (Fig. 9). These results imply that ERK1/2 activation is required for the signaling transduction from FcγR cross-linking to cyclin D1 expression in BMM.

FIGURE 9.

Cyclin D1 expression in BMM after FcγR cross-linking in the presence of the ERK- and Syk-specific inhibitors. BMM were seeded on IgG1-coated culture plates for FcγR cross-linking assay (IgG1), and BSA-coated culture plates were used as the negative control (data not shown). Specific ERK inhibitors PD98059, U0126, and Syk inhibitor Piceatannol were used to block the activation of the ERK signaling pathway triggered by FcγR cross-linking. Macrophage cell contents were extracted after incubation for 0, 2, 5, 8, and 11 h. Cyclin D1 expression levels in the cell extracts after FcγR cross-linking assay were probed using Western blotting analysis and anti-cyclin D1 antibody. β-Tubulin staining was used to control for equal loading of each sample. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

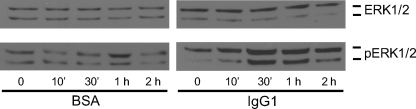

Previous studies reported that FcγR cross-linking activated the macrophage ERK pathway (14, 15). To confirm ERK1/2 activation by FcγR cross-linking in our experimental system, ERK1/2 and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels in BMM were measured by Western blot after stimulation by FcγR cross-linking (Fig. 10). In the control group where BSA was used to coat cell culture plates, background activity of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was observed (BSA). At 1-h poststimulation, a small increase of phosphorylated ERK1/2 was detected, which might be caused by stimulation of BSA. In the macrophages stimulated with FcγR cross-linking, a transient but strong induction of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was seen as early as 30-min poststimulation that waned after 2 h (IgG1). These results confirm that FcγR cross-linking on macrophages activated ERK1/2, which then presumably triggered the cell cycle machinery.

FIGURE 10.

ERK1/2 and phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) expression in BMM after FcγR cross-linking. BMM were seeded on IgG1-coated culture plates for the FcγR cross-linking assay (IgG1), and BSA-coated culture plates were used as the negative control (BSA). Macrophage cell contents were extracted after incubation for 0, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, and 2 h. Total ERK1/2 and pERK1/2 levels in cell extracts after FcγR cross-linking assay were detected using Western blotting with the antibodies as indicated. The data shown are from three independently repeated experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed cell proliferation of both BMM and PM stimulated by FcγR activation. This effect was a consequence of cross-linking of the activating FcγR including FcγRI and III as the Fcγ subunit was required. We established that cyclin D1 protein expression is downstream of FcγR activation, requires Syk and is an initial activation step of the cell cycle machinery of BMM. In addition, we documented the activation of several other important cell cycle proteins including cyclin E, cyclin A, CDK2, CDK4, p21, and Rb phosphorylation after FcγR cross-linking. The ERK signaling pathway was further implicated as a potential mediator of signals from FcγR activation to cyclin D1. Although FcγR activation is known to trigger ERK signaling (8) and ERK signaling has been implicated in cell cycle progression (50), this study establishes a connection from FcγR activation to cell cycle progression through ERK signaling. Consequently, these results provide a causal link between our prior observations that phagocytosis led to cell proliferation of macrophages and provide further support for emerging view of macrophages as a proliferation-capable cellular population of innate immune effector cells. Results may have wide implications for host defense, microbial pathogenesis, and potentially for therapy of infectious, chronic inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases.

FcγR belongs to the immunoreceptor family that also includes the B cell (BCR) and T cell receptor (TCR). Many FcγR share similar functional motifs such as intracellular ITAM domains with BCR and TCR, which are pivotal in their functions (51). The cross-linking of these receptors triggers cell responses through similar signaling pathways. Like FcγR, the activation of BCR and TCR recruit intracellular protein tyrosine kinases such as Src and Syk, which further activate similar various downstream signaling pathways (52, 53). Activation of BCR and TCR can trigger signaling pathways for proliferation of B cells and T cells (54–57). The ERK pathway plays an important role in BCR and TCR activation-induced cell proliferation. Specific ERK inhibitors abolish BCR-dependent proliferation of mature B cells (58). Although we found no prior reports relating the effect of FcγR activation to macrophage proliferation, our data suggest that FcγR activation, like BCR and TCR activation, uses this conserved signaling transduction pathway to trigger cell proliferation of macrophages.

The phenomenon of FcγR cross-linking-stimulated cell proliferation was observed with both BMM and PM but there was a significant quantitative difference in the %Division with BMM > PM. The greater effect observed for BMM relative to PM could reflect the fact that the latter are more differentiated, and consequently, less responsive in vitro. We focused our work on BMM given that %Division after FcγR cross-linking determines the signal-to-noise ratio when comparing activated to non-activated cells for signal transduction events. Hence, we caution that the demonstration of FcγR activation → ERK → cyclin D → mitosis was limited to BMM. Nevertheless, given the conservation of signaling pathways and the qualitative demonstration of the FcγR cross-linking-stimulated cell proliferation with PM, there is a high likelihood that the events shown for BMM also apply to PM.

The signaling transduction pathway leading to cell proliferation after FcγR cross-linking is directly relevant to our prior observation that FcγR-mediated phagocytosis triggered macrophage cell cycle progression (38). Phagocytosis, by definition, is the ingestion of large foreign particles, typically 0.5 μm or larger. It can occur in eukaryotes from unicellular organisms to mammalian cells. It is commonly believed that phagocytosis, an important host defense mechanism in vertebrates, evolved from an ancient nutritional function in unicellular organisms that preserved in extant Protista like Dictyostelium discoideum or Entamoeba histolytica (1, 59). Hence, phagocytosis may be linked to cell division through pathways that signal the acquisition of food, which in turn would imply favorable conditions for replication. The overall molecular mechanistic framework of phagocytosis is highly conserved in evolutionary history, suggesting that this basic cellular process has an ancient origin (1, 59). In contrast to unicellular organisms where phagocytosis serves for food acquisition, phagocytosis in mammalian macrophages functions in part as a host defense mechanism to infectious microbes, and these cells express various FcR to facilitate this process. Cell proliferation after FcγR activation raises interesting questions for the outcome of the interaction of intracellular pathogens and macrophages. Macrophage cell proliferation stimulated by FcγR activation potentially has positive and negative consequences for the host, depending on the likelihood for intracellular survival of ingested microbes and possible distribution pattern of these microbes during the macrophage cell division. Mitosis of macrophages containing intracellular pathogens can generate two infected or one infected and one non-infected cell, depending on the postmitotic distribution of infectious cargo. In prior studies, we have shown that the distribution of cargo to daughter cells is dependent on the number of phagosome formations (60). Given the fact that the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway can be modulated by various microbes (61–63), our findings in the present study suggest that microbes that can modulate the ERK signaling pathway may be able to influence the outcome the intracellular infection by promoting or inhibiting macrophage proliferation.

In addition to phagocytosis, FcγR activation by antibody cross-linking occurs during various other scenarios. For example, a common stimuli for macrophages are immune complexes, which consist of antibody-coated microorganisms, antigens or cell debris, and there is some evidence that immune complexes may trigger macrophage mitosis (26). Circulating immune complexes are abundant in certain conditions including chronic infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV infection and chronic inflammatory conditions such as arthritis and granuloma formation. Proliferation of Kupffer cells, which are specialized macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system of the liver, plays an important role in granuloma formation (64, 65). Particularly, proliferation of macrophages in granuloma formation exists in a CSF-1-independent way (66). In fact, the phenomenon of macrophage cell proliferation following FcγR activation could help account for the observation that antigen-antibody complexes modulate granuloma formation (67, 68) and promote the survival of macrophages in tissue (69). Given that macrophages, acting as a reservoir for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the HIV virus, play a major role in dissemination and persistence of these infections in the infected individuals and that macrophages also play negative roles in the pathogenesis of arthritis, it is conceivable that macrophage proliferation triggered by FcγR cross-linking in these scenarios could promote disease progression. In fact, FcγR cross-linking by circulating immune complex augments HIV replication in monocytes (70). The possibility that macrophage proliferation induced by FcγR cross-linking may play a role in such a process is intriguing.

FcγR activation by antibodies may also play a role in the pathogenesis of certain neoplastic diseases, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML). According to the French-American-British (FAB) classification, AML are classified as myeloblastic, myelomonocytic or monocytic. AML monocytic type is further classified as different subtypes including M4 and M5 that are characterized by intensive FcγR expression. Therefore, FcγR is used as a marker for leukemia typing of M4 and M5 (71, 72). The high proliferation rate of leukemic cells is considered an unfavorable prognostic factor because AML patients with a high number of S-phase cells have shorter survival (73). Conceivably, FcγR is not just a marker for AML typing but could also function as an amplifier for the growth of leukemic cells in the presence of antibody cross-linking. In fact, an early report indicates that humoral immune responses can augment tumor growth and induce a metastatic phenotype (49). In that study, FcγRI cross-linking by circulating immune complex was shown to play a significant role in induction of the growth of tumors, which have FcγR expressed on their cell surface. Interestingly, this phenomenon was observed in a variety of tumor cells including colon cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, and a monocytic cell line, which implies a conservative nature of the linkage between FcγR cross-linking and cell cycle machinery. In contrast to our findings, the PI3K signaling pathway was indicated to mediate the effect of FcγR cross-linking on tumor growth in that study. Nevertheless, given that both the ERK1/2 signaling pathway and the PI3K signaling pathway, which lie downstream of FcγR activation, are deeply involved in the pathogenesis of various malignancies, the clinical relevance of FcγR activation in tumorigenesis may be underestimated and therefore deserves further study.

In conclusion, we show that FcγR activation by antibodies leads to the activation of cell cycle machinery in murine macrophages, a finding that helps to establish a causal link to explain our previous observation that phagocytosis or FcγR activation stimulates macrophage cell proliferation. The cell proliferation activated by FcγR cross-linking is through the activating FcγR, i.e. FcγRI and -III via their Fcγ subunit. The cyclin D1 expression resulting from FcγR cross-linking was mediated by the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Our results implied that activation of FcγR on macrophages may exert a mitogenic effect similar to growth factors and consequently stimulate macrophage proliferation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Matthew D. Scharff and Dianne Cox for valuable discussion. We also thank Drs. Peng Ji, Bo Chen, and Daqian Sun for suggestions on the experiments of Western blotting analysis, immunoprecipitation, and in vitro kinase assay.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI033142, AI033774, AI052733, and HL059842.

- FcR

- Fc receptors

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptors

- BMM

- bone marrow-derived macrophages

- PM

- peritoneal macrophages

- ITAM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- Rb

- retinoblastoma

- CSF-1

- colony-stimulating factor-1

- CFSE

- carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- %Division

- percentage of division

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- FACS

- fluorescent-activated cell sorting

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- BCR

- B cell receptor

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- WT

- wild type

- PI

- propidium iodide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jutras I., Desjardins M. (2005) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 511–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cambier J. C. (1995) J. Immunol. 155, 3281–3285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg S., Chang P., Silverstein S. C. (1993) J. Exp. Med. 177, 529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg S., Chang P., Silverstein S. C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 3897–3902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg S. (1999) J. Leukoc. Biol. 66, 712–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aderem A., Underhill D. M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 593–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Underhill D. M., Ozinsky A. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 825–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-García E., Rosales R., Rosales C. (2002) J. Leukocyte Biol. 72, 107–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibata-Ombetta S., Jouault T., Trinel P. A., Poulain D. (2001) J. Leukoc. Biol. 70, 149–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song X., Tanaka S., Cox D., Lee S. C. (2004) J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durden D. L., Kim H. M., Calore B., Liu Y. (1995) J. Immunol. 154, 4039–4047 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson G. L., Lapadat R. (2002) Science 298, 1911–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karimi K., Lennartz M. R. (1998) Inflammation 22, 67–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cote-Vélez M. J., Ortega E., Ortega A. (1999) Immunol. Lett. 67, 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose D. M., Winston B. W., Chan E. D., Riches D. W., Gerwins P., Johnson G. L., Henson P. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 3433–3438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose D. M., Winston B. W., Chan E. D., Riches D. W., Henson P. M. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238, 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Mejorada G., Rosales C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27610–27619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trotta R., Kanakaraj P., Perussia B. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 184, 1027–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsa K. V., Butchar J. P., Rajaram M. V., Cremer T. J., Tridandapani S. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45, 3012–3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson D. G., Walker C. L. (1999) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 39, 295–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vadiveloo P. K. (1999) J. Leukoc. Biol. 66, 579–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushime H., Ewen M. E., Strom D. K., Kato J. Y., Hanks S. K., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J. (1992) Cell 71, 323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsushime H., Roussel M. F., Ashmun R. A., Sherr C. J. (1991) Cell 65, 701–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daems W. T., de Bakker J. M. (1982) Immunobiology 161, 204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bakker J. M., De Wit A. W., Onderwater J. J., Ginsel L. A., Daems W. T. (1985) J. Submicrosc. Cytol. 17, 133–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes I. J. (1966) J. Immunol. 96, 734–743 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandour D. M., Walker W. S. (1983) J. Immunol. 130, 1108–1112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H., Stewart C. C. (1973) Nat. New Biol. 243, 176–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin H. S., Stewart C. C. (1974) J. Cell Physiol. 83, 369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mims C. A. (1964) Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 45, 37–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murch A. R., Papadimitriou J. M. (1981) J. Pathol. 133, 177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reikvam A. (1976) Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 84, 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawyer R. T., Strausbauch P. H., Volkman A. (1982) Lab. Invest. 46, 165–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart C. C., Lin H. S., Adles C. (1975) J. Exp. Med. 141, 1114–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Zeijst B. A., Stewart C. C., Schlesinger S. (1978) J. Exp. Med. 147, 1253–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker W. S., Beelen R. H. (1988) Cell Immunol. 111, 492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westermann J., Ronneberg S., Fritz F. J., Pabst R. (1989) J. Leukoc. Biol. 46, 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo Y., Tucker S. C., Casadevall A. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 7226–7233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alessi D. R., Cuenda A., Cohen P., Dudley D. T., Saltiel A. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27489–27494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Favata M. F., Horiuchi K. Y., Manos E. J., Daulerio A. J., Stradley D. A., Feeser W. S., Van Dyk D. E., Pitts W. J., Earl R. A., Hobbs F., Copeland R. A., Magolda R. L., Scherle P. A., Trzaskos J. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18623–18632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cannon G. J., Swanson J. A. (1992) J. Cell Sci. 101, 907–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henson P. M. (1971) J. Exp. Med. 134, 114s–135s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takemura R., Stenberg P. E., Bainton D. F., Werb Z. (1986) J. Cell Biol. 102, 55–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casadevall A., Mukherjee J., Devi S. J., Schneerson R., Robbins J. B., Scharff M. D. (1992) J. Inf. Dis. 165, 1086–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan R., Casadevall A., Spira G., Scharff M. D. (1995) J. Immunol. 154, 1810–1816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen B., Pollard J. W. (2003) Mol. Endocrinology 17, 1368–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2006) Immunity 24, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliver J. M., Burg D. L., Wilson B. S., McLaughlin J. L., Geahlen R. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29697–29703 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson M. B., Nyhus J. K., Oravecz-Wilson K. I., Barbera-Guillem E. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 115–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kortylewski M., Heinrich P. C., Kauffmann M. E., Böhm M., MacKiewicz A., Behrmann I. (2001) Biochem. J. 357, 297–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latour S., Veillette A. (2001) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeFranco A. L. (1997) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9, 296–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gold M. R., Matsuuchi L. (1995) Int. Rev. Cytol. 157, 181–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Defranco A. L., Raveche E. S., Asofsky R., Paul W. E. (1982) J. Exp. Med. 155, 1523–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeFranco A. L., Kung J. T., Paul W. E. (1982) Immunol. Rev. 64, 161–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanguay D. A., Chiles T. C. (1996) J. Immunol. 156, 539–548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reid S., Snow E. C. (1996) Mol. Immunol. 33, 1139–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richards J. D., Davé S. H., Chou C. H., Mamchak A. A., DeFranco A. L. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 3855–3864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voigt H., Guillen N. (1999) Cellular Microbiology 1, 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo Y., Alvarez M., Xia L., Casadevall A. (2008) PLoS ONE 3, e3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y. C., Wang Y., Li J. Y., Xu W. R., Zhang Y. L. (2006) World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 5972–5977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mukherjee S., Keitany G., Li Y., Wang Y., Ball H. L., Goldsmith E. J., Orth K. (2006) Science 312, 1211–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhattacharyya A., Pathak S., Datta S., Chattopadhyay S., Basu J., Kundu M. (2002) Biochem. J. 368, 121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naito M., Takahashi K. (1991) Lab. Invest. 64, 664–674 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamada M., Naito M., Takahashi K. (1990) J. Leukoc. Biol. 47, 195–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naito M., Umeda S., Takahashi K., Shultz L. D. (1997) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 46, 85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ridley M. J., Marianayagam Y., Spector W. G. (1982) J. Pathol. 136, 59–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blom A. B., van Lent P. L., Holthuysen A. E., van den Berg W. B. (1999) Cytokine 11, 1046–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marsh C. B., Pomerantz R. P., Parker J. M., Winnard A. V., Mazzaferri E. L., Jr., Moldovan N., Kelley T. W., Beck E., Wewers M. D. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 6217–6225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsitsikov E. N., Fuleihan R., McIntosh K., Scholl P. R., Geha R. S. (1995) Int. Immunol. 7, 1665–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scott C. S., Bynoe A. G., Linch D. C., Allen C., Hough D., Roberts B. E. (1983) J. Clin. Pathol. 36, 555–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krasinskas A. M., Wasik M. A., Kamoun M., Schretzenmair R., Moore J., Salhany K. E. (1998) Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 110, 797–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vidriales M. B., Orfao A., López-Berges M. C., González M., López-Macedo A., Ciudad J., López A., Garcia M. A., Hernández J., Borrego D. (1995) Br. J. Haematol. 89, 342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]