Abstract

Context

Ginkgo biloba is widely used for its potential effects on memory and cognition. To date, adequately powered clinical trials testing the effect of G biloba on dementia incidence are lacking.

Objective

To determine effectiveness of G biloba vs placebo in reducing the incidence of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer disease (AD) in elderly individuals with normal cognition and those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in 5 academic medical centers in the United States between 2000 and 2008 with a median follow-up of 6.1 years. Three thousand sixty-nine community volunteers aged 75 years or older with normal cognition (n=2587) or MCI (n=482) at study entry were assessed every 6 months for incident dementia.

Intervention

Twice-daily dose of 120-mg extract of G biloba (n=1545) or placebo (n=1524).

Main Outcome Measures

Incident dementia and AD determined by expert panel consensus.

Results

Five hundred twenty-three individuals developed dementia (246 receiving placebo and 277 receiving G biloba) with 92% of the dementia cases classified as possible or probable AD, or AD with evidence of vascular disease of the brain. Rates of dropout and loss to follow-up were low (6.3%), and the adverse effect profiles were similar for both groups. The overall dementia rate was 3.3 per 100 person-years in participants assigned to G biloba and 2.9 per 100 person-years in the placebo group. The hazard ratio (HR) for G biloba compared with placebo for all-cause dementia was 1.12 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94–1.33; P=.21) and for AD, 1.16 (95% CI, 0.97–1.39; P=.11). G biloba also had no effect on the rate of progression to dementia in participants with MCI (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.85–1.50; P=.39).

Conclusions

In this study, G biloba at 120 mg twice a day was not effective in reducing either the overall incidence rate of dementia or AD incidence in elderly individuals with normal cognition or those with MCI.

The prevention of disabling chronic diseases in elderly individuals is a major clinical and public health goal. Dementia, especially Alzheimer disease (AD), is a prevalent chronic disease currently affecting more than 5 million people in the United States1 and is a leading cause of age-related disability and long-term care placement.1–4 The herbal product Ginkgo biloba is prescribed in some areas of the world for preservation of memory; however, there are no medications approved for primary prevention of dementia. In the United States, worldwide sales of G biloba exceed $249 million annually.5

Oxidative stress may accelerate the cascade of AD pathological changes that can lead to dementia and cerebrovascular disease. A major mechanism by which G biloba is proposed to exert its effect is by action of multiple antioxidants.6 More recently, an in vitro study indicated that ginkgo extract has an anti-amyloid aggregation effect, suggesting another mechanism whereby G biloba may be beneficial in dementia prevention.7

Clinical trials of efficacy of G biloba have focused primarily on patients with dementia. In 1998, a meta-analysis of early trials reported a small benefit, but a Cochrane Collaboration Review in 2007 found that the evidence for benefit of G biloba on cognition in individuals with dementia was not convincing.8,9 An intention-to-treat analysis from one trial involving individuals already diagnosed with AD showed a small positive effect size over 52 weeks but also experienced a dropout rate approaching 50%.10 Several small, short-term randomized trials have had mixed results.11–13

To date, no adequately designed and powered clinical trial has evaluated the safety and effectiveness of G biloba in the primary prevention of dementia. A recently reported feasibility trial randomized 118 older adults, mean age 87 years, to 240 mg daily of G biloba vs placebo and did not find a reduction in dementia incidence after an average follow-up of 3.5 years in an intention-to-treat analysis.14 Retention and adherence in this feasibility trial were excellent, reflecting improved methods and growing experience over the past decade in conducting clinical trials in older populations. Because of the increasing public health need for effective dementia prevention therapies based on clinical trial evidence, 2 well-powered long-term clinical trials were initiated during the past decade to assess the effectiveness of G biloba in dementia prevention, one in the United States and, more recently, one in Europe.15

We report here the results of the first completed of these 2 trials, the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) Study, a randomized, double-blind trial sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with the collaboration and support of several other institutes and offices.16,17

METHODS

Participants

Volunteers aged 75 years or older were recruited from September 2000 to June 2002 using voter registration and other purchased mailing lists from 4 US communities with academic medical centers: Hagerstown, Maryland (Johns Hopkins); Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (University of Pittsburgh); Sacramento, California (University of California–Davis); and Winston-Salem and Greensboro, North Carolina (Wake Forest University). All participants were required to identify a proxy willing to be interviewed every 6 months at the time of each study visit. Signed informed consent was obtained from participants and their respective proxies.

Individuals with prevalent dementia (meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Fourth Edition] [DSM-IV] criteria for dementia18 or a score >0.5 on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale19 [CDR]) were excluded from participation. Also excluded were individuals meeting any of the following criteria: (1) currently taking the anticoagulant warfarin; (2) taking cholinesterase inhibitors for cognitive problems or dementia (memantine had not been approved for use in the United States when the study began); (3) unwilling to discontinue taking over-the-counter G biloba for the duration of the study; (4) currently being treated with tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics, or other medications with significant psychotropic or central cholinergic effects (the anticholinergic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were not believed to be substantial enough to warrant exclusion); (5) daily use of more than 400-IU vitamin E or unwillingness to reduce intake to this level; (6) history of bleeding disorders; (7) hospitalization for depression within the last year or electroconvulsive therapy within last 10 years; (8) history of Parkinson disease or taking anti-Parkinson medications; (9) abnormal thyroid tests, serum creatinine level greater than 2.0 mg/dL (to convert to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4), or liver function tests more than 2 times the upper limit of normal at baseline; (10) baseline vitamin B12 levels 210 pg/mL or lower (to convert to pmol/L, multiply by 0.7378); (11) hematocrit level less than 30%; (12) platelet count lower than 100 ×103/μL; (13) disease-related life expectancy of less than 5 years; or (14) known allergy to G biloba.

The recruitment procedures for the GEM Study have been described elsewhere.17 Participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) were not excluded. The criteria for classification of MCI at baseline in the GEM Study were based on guidelines set forth by the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment.20,21 In brief, individuals defined as having baseline MCI met both of the following 2 criteria: (1) impaired at or below the 10th percentile of Cardiovascular Health Study normative data, stratified by age and education, on at least 2 of 10 selected neuropsychological test scores from each cognitive domain, including memory, language, visuospatial abilities, attention, and executive function; and (2) CDR global score of 0.5.

Study Intervention

Participants were randomized to twice-daily doses of either 120-mg G biloba extract (EGb 761; Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany) or an identically appearing placebo. The formulation EGb 761 is used in many of the branded ginkgo products sold in the United States. Selection of the specific formulation of G biloba to be used in the study was made following a separate NCCAM “Request for Product” for a company to provide G biloba product of consistent prespecified composition in blister pack format with equal amounts of identically packaged, identically appearing placebo tablets, sufficient to complete the study. The composition of EGb 761 as tested in this trial was described in detail previously.11,16 The 240-mg dose of EGb 761 was chosen based on information from prior clinical studies suggesting a dose-response relationship up to 240 mg.8,11,13,22 Moreover, this dose is commonly used. The composition of the placebo and active tablets was confirmed by independent laboratory analysis for each lot of tablets used during the trial (eTable 1; http://www.jama.com).

Treatment adherence and participant retention were a particular focus in this trial because of the age of the study population. For treatment adherence monitoring, participants returned all blister packs at each 6-month visit, and adherence was calculated using the number of pills taken vs number of days since previous visit. Additionally, an adherence and retention subcommittee led by a geriatrician met monthly to review and discuss challenges to adherence and retention with field center staff and to provide study-specific adherence and retention tracking data to each field center. Annual site visits to all clinics and a midstudy retreat for field center staff focused extensively on strategies for participant adherence and retention specific to this age group.

Randomization

Assignment to G biloba or placebo was determined by permuted block design by site to ensure that allocation between treatment groups was well balanced. Randomization was done separately for each clinical site using a computer-generated, randomly permuted list maintained at the data coordinating center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and each participant was assigned a batch number used throughout the study. All clinical center and coordinating center personnel and participants were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. Only the study pharmacist who allocated the medication into batches, as well as 2 data coordinating center personnel responsible for monitoring serious adverse events and reporting to the study data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), knew which medication was active, but all of these personnel were unaware of participant information. Study statisticians and the DSMB reviewed unblinded data for safety and efficacy, but strict confidentiality of interim results was maintained. To determine efficacy of blinding, the 1993 participants who completed an exit interview were asked to guess to which group they were assigned. A total of 1208 (60.6%) believed they were taking placebo, and 785 (39.4%) believed they were taking G biloba. In terms of actual drug assignments, 61.2% of those taking placebo and 40.0% of those taking G biloba guessed correctly.

Specific Objectives and Hypotheses

The GEM Study tested the primary hypothesis that 240 mg of G biloba daily would decrease the incidence of all-cause dementia and specifically reduce the incidence of AD. Secondary objectives in the GEM Study were to evaluate the effect of G biloba on the following end points: overall cognitive decline, functional disability, total mortality, and incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (defined as the combined incidence of confirmed coronary heart disease, angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, coronary artery bypass surgery, or angioplasty; incidence was confirmed by review of the participant’s medical record after a self-report). The first 2 outcomes will be reported separately.

Study Outcomes

The primary efficacy end point was the diagnosis of dementia by DSM-IV criteria18 as determined by an expert panel of clinicians using an adjudication process previously validated in a similar population.23 When a participant’s scores declined a prespecified number of points from his or her study entry scores on 2 of 3 tests—the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MSE),24 the CDR,19 or the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog)25—he or she was required to undergo the full GEM Study Neuropsychological Battery (NPB) (Box),26–35 which had been completed at study entry. In addition to algorithmic failure of the preliminary battery, participants were also re-administered the full NPB if they or their proxy reported the onset of a new memory or other cognitive problem; there was a diagnosis of dementia by a private physician since the prior visit; or they were prescribed a medication for dementia, such as a cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, by a personal physician.

Box.

GEM Study Neuropsychological Battery of Cognitive Test Variables and Domains Included in Cognitive Impairment Case Identification

| Memory | Attention/psychomotor speed |

|---|---|

| Verbal: California Verbal Learning Test–long delayed free recall | WAIS-R digit span forward (total score) |

| Visual: 24-point modified Rey Osterrieth figure–delayed recall | Trail Making Test A (time in seconds) |

| Construction | Executive functions |

| 24-point modified Rey Osterrieth figure–copy condition | Trail Making Test B (time in seconds) |

| 24-point modified Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised (WAIS-R) block design | Stroop color/word test–interference condition, number of colors named |

| Language | Premorbid intellectual functioning |

| 30-item Boston Naming Test | National Adult Reading Test–American version |

| Animal fluency | Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices |

Results from the full NPB and all clinical assessments were then reviewed by an expert panel blinded to treatment assignment. The panel consisted of 2 neurologists with expertise in dementia diagnosis; 2 neuropsychologists experienced in cognitive assessment of dementia; and a psychometrician with extensive experience in training, administration, and scoring of the CDR. Based on the test battery listed in the Box, participants were considered to have reached dementia outcome in the GEM Study if any of the following applied:

Incident abnormal scores were made on 5 or more tests, and at least 1 of the abnormal scores was on a memory test.

Incident abnormal scores were made on 4 tests, at least 1 of the abnormal scores was on a memory test, and the participant failed to complete 1 or more of the other neuropsychological tests.

Incident abnormality in 2 or more cognitive domains (participant scored below cutoff for age- and education-adjusted norms in both tests of that domain) and 1 of those domains was memory.

Participants classified as reaching dementia end point at this point were then referred for a full neurological evaluation and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan at the clinical site to confirm that the participant met clinical criteria for dementia and assess for atypical causes of dementia. After this examination, the GEM Study dementia adjudication panel, blinded to treatment assignment, reviewed all confirmed cases again to assign a specific dementia classification. This final review incorporated study-related assessments and clinical information, the clinical site neurologist’s clinical report, and the MRI scan (or computed tomographic scan of the brain if the participant was unable to undergo MRI). The MRIs were reviewed according to a standard protocol by 2 board-certified neuroradiologists, also blinded to treatment assignment, and ratings were given for cortical atrophy; ventricular size; subcortical white matter lesions; and presence, size, and number of brain infarcts. These data and the neuroradiologists’ clinical readings were available to the adjudication panel in its diagnostic decision-making, and the adjudicating neurologists also reviewed the scans themselves as part of their diagnostic process.

Specific diagnostic criteria were used for designation of dementia classification. Using criteria from the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS), Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA),36 the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN),37,38 and the Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (ADDTC),39 all participants were assigned to 1 of the following specific dementia diagnosis classifications: (1) Alzheimer dementia; (2) Alzheimer dementia and vascular dementia (participants meeting both NINCDS and ADRDA criteria for AD and ADDTC criteria for possible/probable vascular dementia); (3) vascular dementia (with no AD); or (4) dementia, other etiology (dementia with Lewy bodies, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, etc).

Sample Size

In the calculation of the sample size, it was assumed that in the placebo group, the rate of dementia would be 4% per year and that the combined mortality and dropout rate would be 6% per year based on limited data from observational studies.17 With the use of these estimates, the planned sample size of 3000 with an average follow-up of 5.0 years results in 96% power to detect a 30% reduction in the rate of dementia at a 2-sided significance level of .05. Under these assumptions, the expected total number of dementia cases at the conclusion of the trial would be 439. The sample size also provided adequate power (86%) to detect a 25% reduction in risk.

Because of the uncertainties of the estimate of the dementia rate, the study protocol contained a provision allowing the continuation of the study beyond 5 years until the total of 439 dementia cases occurred, if approved by the DSMB of the study and the funding agency.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using an intention-to-treat approach. The primary analysis compared the time to dementia in the G biloba vs the placebo groups using the log-rank test. Components of the primary end point (AD, other dementias) and subgroups were analyzed in a similar manner. Participants were censored at date of last contact or date of death if all scheduled visits were completed. The first visit occurred in September 2000 and the final visit was completed in April 2008. For those participants with a diagnosis of dementia, the date of onset of the dementia was estimated as the date midway between the last clinic examination at which the participant was not demented and the examination at which the dementia diagnosis was made.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and log-rank tests. Additional Cox model regressions were done adjusting for sex, age, race/ethnicity, MCI, apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, and history of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, bypass surgery, or angioplasty) at baseline, and tests were made of the interactions of these factors with the treatment assignment. Race/ethnicity was self-defined American Indian or Alaska Native, based on NIH-specified categories (ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino; race of Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or white) and was evaluated for descriptive purposes.

Testing for proportional hazards used Schoenfeld residuals. The cumulative event curves were estimated by the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) method. t Tests for the continuous variables and χ2 tests for the discrete variables were used in the non–time-to-event analyses shown in the tables. P<.05 was considered significant and all testing was 2-sided. The few subgroup analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses were done using Stata version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Safety Monitoring and Stopping Guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all universities involved in the study in addition to the NIH. An independent DSMB was appointed by the primary study sponsor, the NCCAM of the NIH. The study was conducted under an investigational new drug application with the Food and Drug Administration under the auspices of NCCAM and registered at clinicaltrials.gov.

An interim analysis test for early stopping of the trial for either efficacy or harm was performed when approximately one-half of the expected number of events had occurred with an α = .005 using a group sequential boundary, preserving the overall trial α =.05.40 The DSMB voted to continue the study at the time of the interim analysis. Interim analyses of serious adverse events were monitored on a quarterly basis at the data coordinating center and results sent to the DSMB if determined to need further review. The DSMB reviewed all trial safety data on an annual basis.

RESULTS

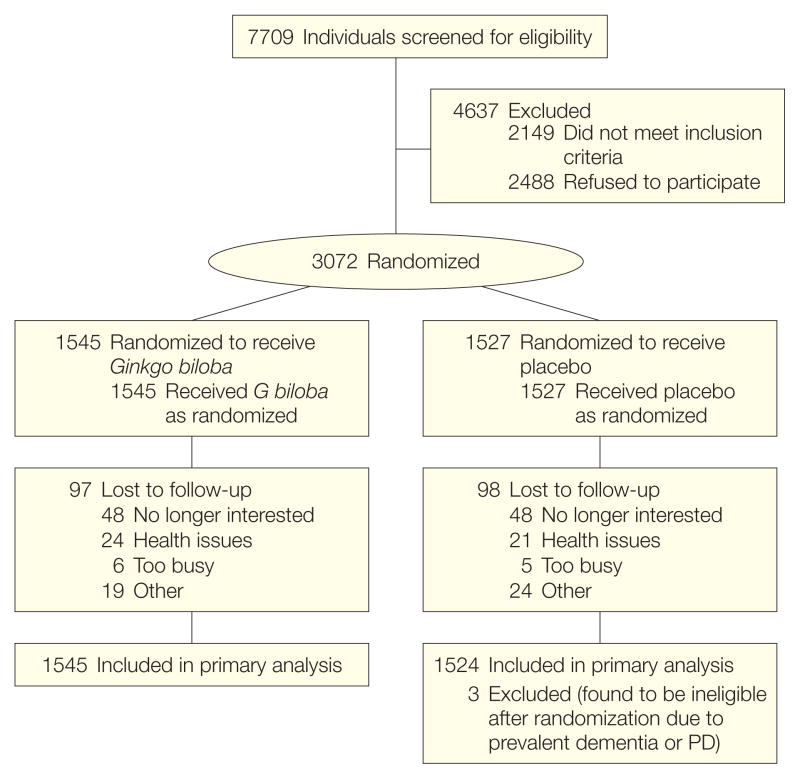

The flow diagram for the 3069 participants randomized to either placebo (n=1524) or G biloba (n=1545) during the enrollment period from September 2000 to June 2002 is shown in Figure 1. The G biloba and placebo groups were similar in their baseline characteristics. Mean age at entry for all participants was 79.1 years and 46% were women (Table 1). Because of a lower-than-expected dementia rate early in the trial, study follow-up was extended in 2006. After reaching the required number of dementia outcomes (n=439), participant closeout was initiated in October 2007 and completed in April 2008. Median follow-up at closeout was 6.1 years (maximum, 7.3 years). Although the dementia rate was extremely low during the first year (<1% in both treatment groups), the rate steadily increased over the remainder of the study follow-up.

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants Through the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) Study

PD indicates Parkinson disease.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants by Study Drug Assignment (Ginkgo biloba vs Placebo)

| No. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 1524) | Ginkgo (n = 1545) | P Valuea | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 79.1 (3.3) | 79.1 (3.3) | .88 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 716 (47) | 702 (45) | .39 | |

| Male | 808 (53) | 843 (55) | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 1448 (95) | 1482 (96) | .23 | |

| Nonwhite | 76 (5) | 63 (4) | ||

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 534 (35) | 570 (37) | .40 | |

| Some college | 395 (26) | 380 (25) | ||

| College graduate | 229 (15) | 250 (16) | ||

| Postgraduate | 366 (24) | 344 (22) | ||

| Medical history | ||||

| Any CVDb | 394 (25.9) | 392 (25.4) | .76 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 152 (10) | 148 (10) | .50 | |

| Heart failure | 33 (2) | 28 (2) | .62 | |

| Stroke | 45 (3) | 43 (3) | .37 | |

| Hypertension | 832 (55) | 833 (54) | .71 | |

| Diabetes | 138 (9) | 139 (9) | .18 | |

| Cancer (past 5 y) | 281 (18) | 283 (18) | .61 | |

| Cognitive test scores | ||||

| 3MSE, mean (SD) | 93.3 (4.7) | 93.3 (4.7) | .76 | |

| CDR score of 0 | 922 (61) | 910 (59) | .69 | |

| CDR score of 0.5 | 600 (39) | 631 (41) | ||

| ADAS-Cog, mean (SD) | 6.4 (2.7) | 6.5 (2.8) | .17 | |

| Difficulty with Activities of Daily Living (score of 1 or more) | 269 (18) | 273 (18) | .99 | |

| Gait speed, mean (SD), seconds to walk 15 ft | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.2) | .20 | |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD) | ||||

| Systolic, mm Hg | 133 (18.4) | 133 (18.1) | .36 | |

| Diastolic, mm Hg | 69.0 (9.9) | 68.8 (9.9) | .71 | |

| Body mass indexc | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 14 (1) | 12 (1) | .62 | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 478 (31) | 482 (31) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 687 (45) | 724 (47) | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 341 (22) | 319 (21) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 622 (42) | 602 (40) | .51 | |

| Former | 805 (53) | 846 (56) | ||

| Current | 65 (4) | 71 (5) | ||

| Mild cognitive impairment at baseline | 226 (14.8) | 256 (16.6) | .18 | |

| APOE genotype: presence of ε4 alleled | 281 (23.0) | 297 (24.1) | .52 | |

Abbreviations: 3MSE, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; ADAS-Cog, cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

P values computed using χ2 (discrete variables) or t test (continuous variables).

Defined as coronary heart disease, angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, bypass surgery, or angioplasty.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Apolipoprotein E genotype was available for 2454 individuals.

During the intervention period, 523 participants were diagnosed with dementia, 246 (16.1%) in the placebo group and 277 (17.9%) in the G biloba group. There were 379 deaths from any cause. Cognitive status was known for 93.6% of all participants at trial end. There were 195 individuals (6.3%) who were either lost to follow-up or withdrew consent (97 in the G biloba group and 98 in the placebo group). The 195 participants who declined to continue the study after randomization did not differ from the 2874 who remained in the study by age, sex, minority race/ethnicity, baseline disease categories (eg, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, cancer), or smoking status. However, a difference in MCI status at baseline was found with 22.6% of dropouts classified with this condition compared with 15.2% of those who completed the study (P=.01).

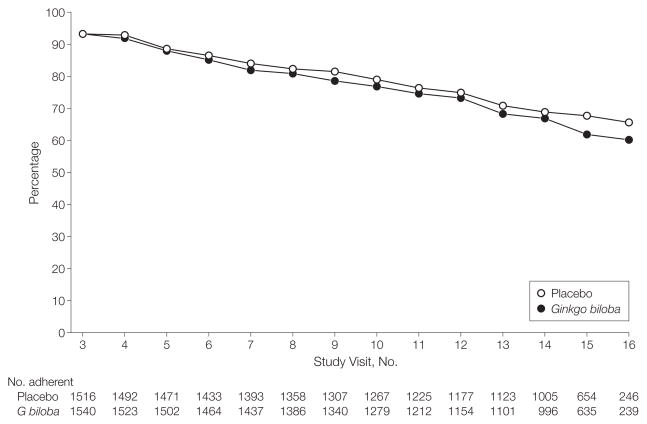

As shown in Figure 2, at the end of the trial, 60.3% of active participants were taking their assigned study medication, and adherence did not differ between the 2 groups. Because of a concern about possible drug interaction increasing the risk of bleeding, initiation of warfarin therapy was specifically stated in the protocol as a reason for discontinuing the study medication. Institution of warfarin therapy resulted in participant discontinuation of assigned study medication in 214 participants (15.4% of total discontinuations), 112 in the G biloba group and 102 in the placebo group. Neither missing cognitive function assessment nor study medication discontinuation differed significantly by assigned treatment group. A total of 161 participants (86 taking G biloba and 75 taking placebo) initiated cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine during the study.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Adherence to Assigned Study Tablets by Scheduled 6-Month Follow-up Visit (Excluding Death and Incident Dementia)

Study visit No. 3 was the first 6-month follow-up visit after randomization.

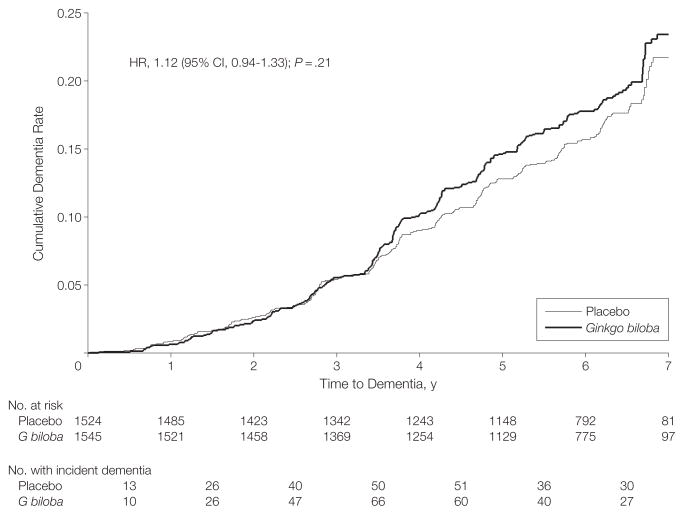

Figure 3 shows the cumulative rate of all-cause dementia by treatment with G biloba vs placebo during the course of the GEM Study. The 2 primary outcomes were all-cause dementia and AD. Of the total dementia cases, 92% were classified as AD. The rates of overall dementia and dementia by subtype for participants assigned to G biloba vs placebo in the GEM Study are compared in Table 2. The rate of total dementia did not differ between participants assigned to G biloba vs placebo (3.3/100 person-years vs 2.9/100 person-years; HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.94–1.33; P=.21), and as also shown in Table 2, the rate of Alzheimer-type dementia also did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (3.0/100 person-years vs 2.6/100 person-years; HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.97–1.39; P=.11). The results were no different when the end point was AD only vs AD with evidence of vascular disease of the brain (Table 2). There was no evidence for effect modification by age, sex, or MCI (tests for interaction, P = .16, P = .54, and P = .94, respectively).

Figure 3.

Cumulative Dementia Rates by Treatment

CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 2.

Incidence Rates (per 100 Person-Years) and Hazard Ratios From Cox Regression Analyses: All Dementia and Subtypes of Dementia Comparing G biloba With Placebo for All Participants and Those Classified at Baseline With Normal Cognition and Mild Cognitive Impairment

| All Participants (N = 3069) | Baseline Normal Cognition (n = 2587) | Baseline MCI (n = 482) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate (No. of Events) | Rate (No. of Events) | Rate (No. of Events) | ||||||||||

| Outcome | Placebo (n = 1524) | G biloba (n = 1545) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Placebo (n = 1298) | G biloba (n = 1289) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Placebo (n = 226) | G biloba (n = 256) | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| All dementia | 2.94 (246) | 3.27 (277) | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | .21 | 2.16 (159) | 2.25 (165) | 1.05 (0.84–1.30) | .67 | 8.68 (87) | 9.82 (112) | 1.13 (0.85–1.50) | .39 |

| Alzheimer without vascular dementiaa | 1.92 (161) | 2.27 (192) | 1.18 (0.97–1.46) | .11 | 1.36 (100) | 1.53 (112) | 1.13 (0.86–1.48) | .36 | 6.09 (61) | 7.02 (80) | 1.15 (0.83–1.61) | .40 |

| Alzheimer with vascular dementiab | 0.71 (59) | 0.77 (65) | 1.09 (0.77–1.55) | .63 | 5.02 (37) | 5.60 (41) | 1.12 (0.72–1.74) | .63 | 2.20 (22) | 2.10 (24) | 0.96 (0.54–1.71) | .89 |

| Total Alzheimer dementia | 2.63 (220) | 3.04 (257) | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | .11 | 1.86 (137) | 2.09 (153) | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) | .30 | 8.28 (83) | 9.12 (104) | 1.10 (0.83–1.47) | .51 |

| Vascular dementia without Alzheimer dementia | 0.20 (17) | 0.08 (7) | 0.41 (0.17–0.98) | .05 | 0.19 (14) | 0.07 (5) | 0.36 (0.13–1.00) | .05 | 0.30 (3) | 0.18 (2) | 0.59 (0.10–3.51) | .56 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; G biloba, Ginkgo biloba; HR, hazard ratio; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Meeting NINCDS (National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke) criteria for probable or possible Alzheimer disease without vascular dementia.

Meeting ADDTC criteria (Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers) for probable or possible vascular dementia.

In an exploratory analysis, there was a statistically significant interaction with treatment in those participants reporting a history of CVD at baseline (P=.02). The adjusted HR for dementia for those participants free of CVD at baseline was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.79–1.20; P = .81). For the smaller subgroup of those with CVD at baseline (394 placebo, 392 G biloba), the HR was 1.56 (95% CI, 1.14–2.15; P = .006). Table 2 also shows the HR for G biloba compared with placebo for the secondary end point of vascular dementia. Only 24 individuals were classified as having new-onset vascular dementia alone (ie, without concomitant AD), and the rate of dementia in this classification for G biloba vs placebo was 0.08 per 100 person-years and 0.20 per 100 person-years, respectively (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17–0.98; P=.05). The test for deviations from proportional hazards for the primary end point of dementia was not significant. Lastly, while APOE genotype for those with at least 1 APOE ε4 allele was associated strongly with incident dementia (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.63–2.96; P<.001), there was no evidence of any interaction between APOE status and treatment (P=.75).

The adverse event profiles for G biloba and placebo were similar and there were no statistically significant differences in the rate of serious adverse events, as shown in Table 3. The mortality rate was similar in the 2 treatment groups (Table 3) (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.85–1.26; P = .72). There were no differences in the incidence of coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, angina, angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass graft) or stroke of any type by treatment group. Of particular note, as shown in Table 3, rates of major bleeding did not differ between the treatment groups (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.77–1.23; P=.81), and bleeding incidence did not differ for individuals taking aspirin and assigned to either G biloba or placebo (rates of 1.98 and 1.76 per 100 person-years, respectively, P = .44). Although there were twice as many hemorrhagic strokes in the G biloba group compared with the placebo group (16 vs 8), the number of cases was small and nonsignificant in the analysis. A complete listing of the rates of adverse events by organ system can be found online (eTable 2).

Table 3.

Specific Serious Adverse Events

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Placebo | Ginkgo Biloba | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Death | 188 (12.3) | 197 (12.8) | 1.04 (0.85–1.26) | .72 |

| Bleeding, total | 140 (9.2) | 138 (8.9) | 0.97 (0.77–1.23) | .81 |

| Gastrointestinal | 77 (5.1) | 83 (5.4) | 1.06 (0.78–1.45) | .70 |

| All other | 71 (4.7) | 64 (4.1) | 0.89 (0.64–1.25) | .52 |

| CHD total | 204 (13.4) | 211 (13.7) | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | .83 |

| Myocardial infarction | 76 (5.0) | 90 (5.8) | 1.18 (0.87–1.59) | .30 |

| Angina | 99 (6.5) | 107 (6.9) | 1.06 (0.81–1.40) | .65 |

| Angioplasty | 65 (4.3) | 79 (5.1) | 1.20 (0.87–1.67) | .27 |

| CABG | 49 (3.2) | 51 (3.3) | 1.02 (0.69–1.52) | .90 |

| CHD death | 47 (3.1) | 48 (3.1) | 1.01 (0.67–1.50) | .98 |

| Stroke, total | 71 (4.7) | 80 (5.2) | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | .50 |

| Ischemic | 62 (4.1) | 62 (4.0) | 0.99 (0.70–1.41) | .96 |

| Hemorrhagic | 8 (0.5) | 16 (1.0) | 1.97 (0.84–4.61) | .12 |

| Unknown | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | ||

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

COMMENT

The GEM Study was conducted to determine whether G biloba would reduce the incidence of dementia because effective treatments for the prevention or delay of onset of dementia are lacking, and there existed promising basic and observational research indicating potential mechanisms and efficacy for G biloba to prevent or delay the onset of dementia with age.7,22,41–47 The preservation of cognitive function in aging is essential to the maintenance of independence and the prevention of institutionalization. A 5-year delay in onset of dementia would result in an approximate 50% decrease in the number of dementia cases after several decades.1 Smaller delays in age at onset, assuming a usual rate of decline in cognitive function after onset, would still result in substantially lower numbers of cases and individuals requiring institutional care. Therefore, testing interventions with the potential to prevent or reduce loss of cognitive function is of high public health importance.

The results from the GEM Study did not show that G biloba is effective in preventing or delaying the onset of all-cause dementia in participants older than 75 years. G biloba also had no effect on the risk for developing AD in this age group. The higher rate of AD in individuals with pre-existing CVD and assigned to G biloba is puzzling and should be viewed with caution given the lack of evidence from published basic science research supporting a potential mechanism for G biloba increasing Alzheimer dementia risk in individuals with CVD. Similarly, the very small number of purely vascular dementia cases identified in the GEM Study (n=24) and the lack of effect on the incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke make any conclusion about the relationship between G biloba and prevention of vascular dementia imprudent. Also, although no firm conclusion can be drawn from the higher number of hemorrhagic strokes in the G biloba group, this finding should be explored in future studies.

To our knowledge, the GEM Study is the largest and first adequately powered randomized clinical trial conducted to evaluate the effect of G biloba on dementia incidence. The GEM Study specifically enrolled a population at increased risk for dementia whose mean age was older than 75 years at initiation of the trial. In addition to the large sample size, strengths of the GEM Study also included its high event rate (after a few years of lower-than-expected incidence), recruitment of individuals living in the community and not seeking care for cognitive complaints, the random assignment of participants, the careful and frequent assessment of cognitive status for dementia incidence according to a common protocol and using prespecified dementia criteria, the high rate of follow-up and treatment adherence in a population at risk for substantial co-morbidity, adjudication of outcomes by an expert committee unaware of study-group assignment, and safety monitoring by an independent committee.

One potential limitation of the trial is that, because the delay from initial brain changes to clinical dementia is known to be long, it is possible that an effect of G biloba, positive or negative, may take many more years to manifest. For this reason, further analysis of brain function and pathology by group is planned using MRIs of a subset of participants. Despite this limitation, the GEM Study is by far the longest prevention trial conducted with this intervention.

These results confirm that randomized trials remain critical to the spectrum of translational research necessary to develop new therapies and to determine whether the purported in vitro, epidemiologic, and surrogate measures of therapeutic benefit are true not only for traditional pharmaceutical therapies but also for complementary therapies. Of almost equal importance from these results is the provision of a strong rationale for including older individuals in randomized trials testing promising interventions for preventing or delaying dementia onset. The GEM Study experienced a rate of refusal or loss to follow-up of only 1.1% per year, a rate similar to or better than the dropout rate for CVD trials in populations much younger than the GEM Study cohort.48,49 Results from the GEM Study are useful for estimating the number of participants needed to provide adequate power to detect clinically meaningful effects on discrete outcomes such as dementia incidence. Future analysis of the GEM Study data may identify subgroups of older adults with generally normal cognition who are at the greatest risk for experiencing dementia.

In summary, in this randomized clinical trial in 3069 older adults with normal cognitive function or mild deficits, G biloba showed no benefit for reducing all-cause dementia or dementia of the Alzheimer type. A central issue in testing of complementary and alternative medications is the formulation of the compounds. This study used a requisite standardized formulation of G biloba extract with specified amounts of the active ingredients in a dosage based on the highest doses used and reported in the literature. The extract we tested is among the best characterized and is the one for which the most efficacy data are available. Thus, we believe that the results are applicable to other G biloba extracts. Based on the results of this trial, G biloba cannot be recommended for the purpose of preventing dementia.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant U01 AT000162 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) and the Office of Dietary Supplements and National Institute on Aging; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50AG05133); Roena Kulynych Center for Memory and Cognition Research; Wake Forest University School of Medicine; and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany, donated the G biloba tablets and identical placebos in blister packs for the study.

Role of the Sponsor: The NCCAM of the National Institutes of Health contributed to the design and conduct of the study as well as analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. Schwabe Pharmaceuticals had no role in the design and conduct of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) Study Investigators: Project Office, NCCAM: Richard Nahin, PhD, MPH; Barbara Sorkin, PhD. Clinical Centers: Michelle C. Carlson, PhD; Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH; Pat Crowley, MS; Claudia Kawas, MD; Paulo Chaves, MD; Sevil Yasar, PhD; Patricia Smith; Joyce Chabot; Johns Hopkins University; John A. Robbins, MD, MHS; Katherine Gundling, MD, FACP; Sharene Theroux, CCRP; Linly Kwong, CCRP; Lisa Pastore, CCRP; University of California–Davis; Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH; Roberta Moyer, CMA; Cheryl Albig, CMA; University of Pittsburgh; Gregory Burke, MD; Steve Rapp, PhD; Dee Posey; Margie Lamb, RN; Wake Forest University School of Medicine. Schwabe Pharmaceuticals: Robert Hörr, MD; Thorsten Schmeller, PhD; Joachim Herrmann, PhD. Data Coordinating Center: Richard A. Kronmal, PhD; Annette L. Fitzpatrick, PhD; Fumei Lin, PhD; Cam Solomon, PhD; Alice Arnold, PhD; University of Washington. Cognitive Diagnostic Center: Steven T. DeKosky, MD; Judith A. Saxton, MD; Oscar L. Lopez, MD; Diane G. Ives, MPH; Leslie Dunn, MPH; University of Pittsburgh. Clinical Coordinating Center: Jeff D. Williamson, MD, MHS; Curt D. Furberg, MD, PhD; Nancy Woolard; Kathryn Bender, PharmD; Susan Margitic, MS; Wake Forest University School of Medicine. Central Laboratory: Russell P. Tracy, PhD; Elaine Cornell, BA; University of Vermont. MRI Reading Center: Carolyn Meltzer, MD, University of Pittsburgh. Data Safety Monitoring Board: Richard Grimm, MD, PhD (chair), University of Minnesota; Jonathan Berman, MD, PhD (executive secretary), NCCAM; Hannah Bradford, MAc, LAc, MBA; Carlo Calabrese, ND, MPH; Bastyr University Research Institute; Rick Chappell, PhD, University of Wisconsin Medical School; Kathryn Connor, MD, Duke University Medical Center; Gail Geller, ScD, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute; Boris Iglewicz, PhD, Temple University; Richard S. Panush, MD, Saint Barnabas Medical Center; Richard Shader, PhD, Tufts University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM or the National Institutes of Health.

Additional Information: eTables 1 and 2 are available at http://www.jama.com.

Additional Contributions: Stephen Straus, MD, the late former director of the NCCAM, championed efforts to evaluate complementary and alternative therapies in rigorous scientific fashion. Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany, donated the G biloba tablets and identical placebos in blister packs for the study. We are grateful to our volunteers, whose faithful participation in this longitudinal study made it possible.

Trial Registration clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00010803

Author Contributions: Dr DeKosky had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: DeKosky, Williamson, Kronmal, Lopez, Burke, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Tracy, Dunn, Nahin, Furberg.

Acquisition of data: DeKosky, Williamson, Ives, Saxton, Lopez, Burke, Carlson, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Tracy, Woolard, Dunn.

Analysis and interpretation of data: DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Saxton, Lopez, Burke, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Tracy, Dunn, Snitz, Nahin, Furberg.

Drafting of the manuscript: DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives, Dunn, Furberg.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Saxton, Lopez, Burke, Carlson, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Tracy, Woolard, Snitz, Nahin, Furberg.

Statistical analysis: Fitzpatrick, Kronmal.

Obtained funding: DeKosky, Kronmal, Burke, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Furberg.

Administrative, technical, or material support: DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives, Saxton, Lopez, Burke, Carlson, Fried, Kuller, Robbins, Tracy, Woolard, Dunn, Furberg.

Study supervision: DeKosky, Williamson, Kronmal, Ives, Saxton, Nahin, Furberg.

Financial Disclosures: Dr DeKosky reported receiving grants or research support from Elan, Myriad, Neurochem, and GlaxoSmithKline; and serving on the advisory boards of or consulting for AstraZeneca, Abbott, Baxter, Daichi, Eisai, Forest, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Medivation, Merck, Neuro-Pharma, Neuroptix, Pfizer, Myriad, and Servier. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(9):1337–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero-Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Guo Z, Viitanen M, von Strauss E, Winblad B. Dementia is the major cause of functional dependence in the elderly: 3-year follow-up data from a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(10):1452–1456. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guralnik JM, Leveille SG, Hirsch R, Ferrucci L, Fried LP. The impact of disability on older women. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1997;52(3):113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magsi H, Malloy T. Underrecognition of cognitive impairment in assisted living facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutritional Business Journal 2006 Supplement Business Report. San Diego, CA: Penton Media Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietri S, Maurelli E, Drieu K, Culcasi M. Cardioprotective and anti-oxidant effects of the terpenoid constituents of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29(2):733–742. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo Y, Smith JV, Paramasivam V, et al. Inhibition of amyloid-beta aggregation and caspase-3 activation by the Ginkgo biloba extract EGb761. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12197–12202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182425199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA. The efficacy of Ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(11):1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.11.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birks J, Grimley EV, Van DM. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD003120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, Itil TM, Freedman AM, Schatzberg AF. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia: North American EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1327–1332. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.16.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider LS, DeKosky ST, Farlow MR, Tariot PN, Hörr R, Kieser M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two doses of Ginkgo biloba extract in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2(5):541–551. doi: 10.2174/156720505774932287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarney R, Fisher P, Iliffe S, et al. Ginkgo biloba for mild to moderate dementia in a community setting: a pragmatic, randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published online June 9, 2008] Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi: 10.1002/gps.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanowski S, Herrmann WM, Stephan K, Wierich W, Hörr R. Proof of efficacy of the ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761 in outpatients suffering from mild to moderate primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer type or multi-infarct dementia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1996;29(2):47–56. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodge HH, Zitzelberger T, Oken BS, Howieson D, Kaye J. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Ginkgo biloba for the prevention of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2008;70(19 pt 2):1809–1817. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303814.13509.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vellas B, Andrieu S, Ousset PJ, Ouzid M, Mathiex-Fortunet H. The GuidAge study: methodological issues: a 5-year double-blind randomized trial of the efficacy of EGb 761 for prevention of Alzheimer disease in patients over 70 with a memory complaint. Neurology. 2006;67(9 suppl 3):S6–S11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.67.9_suppl_3.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeKosky ST, Fitzpatrick A, Ives DG, et al. The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) study: design and baseline data of a randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract in prevention of dementia. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(3):238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick AL, Fried LP, Williamson J, et al. Recruitment of the elderly into a pharmacologic prevention trial: the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(6):541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snitz BE, Saxon J, Lopez OL, et al. Identifying mild cognitive impairment at baseline in the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) Study. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2) doi: 10.1080/13607860802380656. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurer K, Ihl R, Dierks T, Frolich L. Clinical efficacy of Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761 in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(6):645–655. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick A, Ives D, Becker JT, Beauchamp N. Evaluation of dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22(1):1–12. doi: 10.1159/000067110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48 (8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohs RC. The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(2):195–203. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker JT, Boller F, Saxton J, Gonigle-Gibson KL. Normal rates of forgetting of verbal and non-verbal material in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 1987;23 (1):59–72. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(87)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delis DC. California Verbal Learning Test. New York, NY: Psychological Corp; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13(6):933–949. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Jagust WJ, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of mild cognitive impairment subgroups. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):159–165. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raven JC. Guide to Using the Coloured Progressive Matrices. London, England: HK Lewis; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reitan RM. The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955;19(5):393–394. doi: 10.1037/h0044509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saxton J, Ratcliff G, Munro CA, et al. Normative data on the Boston Naming Test and two equivalent 30-item short forms. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;14(4):526–534. doi: 10.1076/clin.14.4.526.7204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Lever WR. STROOP Neuropsychological Screening Test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York, NY: Psychological Corp; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erkinjuntti T. Clinical criteria for vascular dementia: the NINDS-AIREN criteria. Dementia. 1994;5(3–4):189–192. doi: 10.1159/000106721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockwood K, Parhad I, Hachinski V, et al. Diagnosis of vascular dementia: Consortium of Canadian Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research consensus statement. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21(4):358–364. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100040968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chui HC, Mack W, Jackson JE, et al. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of vascular dementia: a multi-center study of comparability and interrater reliability. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(2):191–196. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleming TR, Harrington D, O’Brien P. Designs for group sequential tests. Control Clin Trials. 1984;5(4):348–361. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(84)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auguet M, DeFeudis FV, Clostre F. Effects of Ginkgo biloba on arterial smooth muscle responses to vasoactive stimuli. Gen Pharmacol. 1982;13(2):169–171. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(82)90075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastianetto S, Ramassamy C, Dore S, Christen Y, Poirier J, Quirion R. The Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) protects hippocampal neurons against cell death induced by beta-amyloid. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(6):1882–1890. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunetti L, Orlando G, Menghini L, Ferrante C, Chiavaroli A, Vacca M. Ginkgo biloba leaf extract reverses amyloid beta-peptide-induced isoprostane production in rat brain in vitro. Planta Med. 2006;72(14):1296–1299. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen X, Salwinski S, Lee TJ. Extracts of Ginkgo biloba and ginsenosides exert cerebral vasorelaxation via a nitric oxide pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24(12):958–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawas CH, Brookmeyer R. Aging and the public health effects of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(15):1160–1161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahady GB. Ginkgo biloba for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;16(4):21–32. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcocci L, Maguire JJ, Droy-Lefaix MT, Packer L. The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201(2):748–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) JAMA. 1991;265(24):3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]