Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to determine the usefulness of edible taste strips for measuring human gustatory function.

Research Design

The physical properties of edible taste strips were examined in order to determine their potential for delivering threshold and suprathreshold amounts of taste stimuli to the oral cavity. Taste strips were then assayed by fluorescence to analyze the uniformity and distribution of bitter tastant in the strips. Finally, taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste were examined in order to determine whether or not taste strips would produce recognition thresholds that were equal to or better than those obtained from aqueous tests.

Methodology

Edible strips were prepared from pullulan-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose solutions that were dried to a thin film. The maximal amount of a tastant that could be incorporated in a 2.54 × 2.54 cm taste strip was identified by including representative taste stimuli for each class of tastant (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami) during strip formation. Distribution of the bitter tastant quinine hydrochloride in taste strips was assayed by fluorescence emission spectroscopy. The efficacy of taste strips for evaluating human gustatory function was examined by using a single series ascending method of limits protocol. Sucrose taste recognition threshold data from edible strips was then compared to results that were obtained from a standard “sip and spit” recognition threshold test.

Results

Edible films that formed from a pullulan-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose polymer mixture can be used to prepare clear, thin strips that have essentially no background taste and leave no physical presence after release of tastant. Edible taste strips could uniformly incorporate up to five percent of their composition as tastant. Taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste were over one order of magnitude lower with edible taste strips when compared to an aqueous taste test.

Conclusion

Edible taste strips are a highly sensitive method for examining taste recognition thresholds in humans. This new means of presenting taste stimuli should have widespread applications for examining human taste function in the lab, in the clinic, or at remote locations.

Keywords: gustation, taste test, pullulan, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, sweet taste

INTRODUCTION

When compared to measurements of olfactory function, considerably fewer studies have been reported on human taste perception. One reason for this discrepancy is the absence of a rapid and reliable method for evaluating gustatory function. Recent estimates suggest that approximately 0.6% of the U.S. population experiences a taste problem1. Furthermore, human taste responses are thought to influence dietary2, drug3, and alcohol over-consumption4,5. Thus, a psychophysical taste test that is easy to prepare and easy to transport to locations outside of the clinic or lab should have clinical relevance for measuring taste disturbances.

Taste function in humans is often examined by presenting a variety of aqueous solutions to test subjects6. This approach has certain limitations. For example, water may activate CNS regions that respond to tastants7, and may also cause after-impressions following the removal of a chemical solution from the mouth8;9. In addition, aqueous solutions possess a variable shelf life, raise complications due to the temperature of solutions during testing, and are not easily transported outside the clinic or lab.

Recently, a number of tests have been developed that do not use aqueous solutions for delivery of taste stimuli. The insoluble matrices used in these tests consist of either dried wafer/tablets that contain varying amounts of basic taste stimuli, cellulose-based filter papers that are impregnated with tastant, or starch-based flavor films10–15. While each of these tests meets the requirement for long shelf life, each has limitations. The wafer/tablet tests required that the samples had to be chewed, which negated the opportunity to examine regional testing in the oral cavity. For impregnated paper tests, the filter paper functions as an insoluble substrate that must be expectorated and discarded at the end of each trial. In addition, the filter paper method may yield false negatives or false positives during examination of taste blindness to phenylthiocarbamide16.

One approach for improving the measurement of human gustatory function is to design a delivery system that rapidly dissolves in the oral cavity and has little or no background taste. Such a delivery system will provide the necessary tools for accurately assessing human taste function in a clinical, industrial, or academic setting. In this report, we describe the preparation and use of edible films as a vehicle for rapidly administering precise amounts of one or more tastants into the oral cavity. These films are primarily composed of the naturally occurring polymer pullulan, which is a polysaccharide that is produced from starch by the fungus Aureobasidium pullulans17. The goal of this report is to demonstrate the advantages of edible taste strip technology for examining human taste function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of edible taste strips

For preparation of strips, pullulan (α-1,4; α-1,6-glucan) is combined with the polymer hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC). HPMC is a semi-synthetic ether derivative of cellulose that increases the tensile strength of pullulan films. For preparation of edible films, HPMC powder was first added to a rapidly stirred solution of 100 ml of distilled water at 75–80° C, followed by addition of pullulan powder. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, and tastant was added along with 12 microliters of food coloring to aid in visualization of the strips. Control strips were prepared as described above except no tastant was included. For film preparation, a flat casting surface was washed with 95% ethanol, dried, and wiped clean with a paper towel. Vinyl electrical tape (3M Corporation) was placed on the surface to produce a border that enclosed a 3.25 × 4 inch rectangle. The clear polymer solution was then poured onto either nonstick cookie sheets (Baker’s SecretR) or dry-erase white boards (Office Depot) by adding a 6.94 ml volume of polymer solution within the enclosed rectangle. The solution was evenly spread over the enclosed area, and was allowed to dry for 5 to 6 hours at room temperature or at 37 °C. Dried films were prepared from 3.0 or 3.25% (wt/vol) polymer, with a dry weight ratio of 7:1 pullulan to HPMC. After drying, the clear film was removed in its entirety by gently removing the vinyl tape border, and then removing the film from the surface mold with tweezers or a razor blade. Finally, the film was cut into 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm lengths and stored between sheets of glassine paper in 35 mm cell culture dishes, and placed in a small zip-loc bag. Edible strips were stored in the dark at room temperature or at 4 °C. Figure 1 shows an image of an edible film that was removed from its casting surface.

Fig. 1.

Edible taste strips are readily formed from pullulan-HPMC polymers. This figure is an image of a clear pullulan-HPMC edible film that formed from a 3.25% polymer solution containing 87.5% pullulan and 12.5% HPMC by weight. The clear film is then cut into 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm pieces for psychophysical testing.

Quinine assay for uniformity of tastant

Quinine hydrochloride is a widely used bitter tastant for psychophysical studies18, and this fluorescent molecule was selected as a representative tastant for examining the uniformity of taste stimuli in strips. Quinine hydrochloride was quantified in 3.25% taste strips by fluorescence spectroscopy (PTI, Birmingham, NJ). Edible taste strips were prepared that contained 118.2 micromoles of quinine hydrochloride within each 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm taste strip. After dissolving each taste strip in 3.5 ml of 0.5 M sulfuric acid, quinine content was assayed by fluorescence emission spectroscopy, with excitation at 310 nanometers. Fluorescence emission was measured at the wavelength maximum, and emission was measured in the range where autoquenching of fluorescence did not occur (≤ 50 uMolar). A standard curve for quinine content was generated by measuring peak fluorescence emission of quinine solutions of increasing concentrations (r2 = 0.99 for standard curve).

Psychophysical Measurements

For assessment of sweet taste recognition thresholds, edible taste strips were prepared as described above, except that sucrose was used as the taste stimulus. Control strips contained only pullulan and HPMC. For the “sip and spit” test, sucrose was dissolved in water, and 10 ml aliquots were used for psychophysical measurements. All solutions were used at room temperature.

For taste recognition thresholds, a modification of the three-drop procedure19–20 that utilized a single series ascending method of limits was employed21. In this protocol, taste stimuli were presented in triads (one stimulus and two blanks). The stimulus series was begun with a low amount of tastant in the strip, and the task of the subject was to (a) report which one of the three stimuli differed from the other two, and (b) correctly identify its taste quality (i.e., sweet). When a miss occurred within a triad, a subsequent triad was presented at the next higher stimulus amount. When the first triad was performed correctly, an additional triad was presented where the amount of taste stimulus remained the same. If correct performance again occurred, a third triad was given at the same stimulus concentration. The stimulus amount where three successful triads occurred (where all three successful triads contained the same stimulus amount) was taken as the threshold value if one additional triad was successfully performed that contained the next higher amount of tastant. The probability of correctly guessing the strip with tastant in four successive triads (12 presentations) is 0.01.

Chemicals

Pullulan was obtained from NutriScience Innovations, LLC (Fairfield, CT), and HPMC was from Dow Chemical Co. (Midland MI). Sucrose, monosodium glutamate, 6-propyl-2-thiouracil (n-PROP), and quinine hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). L-ascorbic acid and sodium chloride were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Food coloring (McCormick & Co., Hunt Valley, MD) was obtained from a local supermarket. Lactisole was obtained from Domino Foods Incorporated (Yonkers, NY).

Participants

A total of 41 healthy volunteers (25 males and 16 females) ranging in age from 18 to 58 years (average age of 30.6 years) volunteered to participate. All participants were non-smokers, and each subject was asked to refrain from eating or drinking (except water) for a minimum of one hour prior to their scheduled session. All subjects were healthy by self-report. No subjects had been previously diagnosed with diabetes or neurological disorders such as depression, or had visited a dentist in the previous 48 hours, that would compromise their taste function. For statistical analysis, potential gender differences for sucrose taste recognition studies were carried out with the Mann-Whitney U-Test. Table Curve 2D software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA) was used to analyze cumulative threshold data. The Temple University Human Subjects Review committee fully approved the experimental protocol.

RESULTS

Properties of edible taste strips

Control taste strips (3.0% polymer content) that measured 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm in size weighed on average 20.6 mg, and had an average film thickness of 0.03 mm. The dissolving time for taste strips on the tongue surface was approximately 10 seconds, and dissolving time was 8.4 +/−1.1 seconds in deionized water at 37 °C. Table 1 shows the maximal amount of tastant that can be added to 3.25% pullulan-HPMC strips in order to produce a clear film that is readily removed from its casting surface. The upper limit for representative tastants incorporation in polymer solutions is between 2.5 and 5% (w/v), with ionic compounds saturating the film at lower amounts. Representative taste stimuli of the five major classes of tastants were incorporated into pullulan-HPMC strips at amounts that are routinely used for suprathreshold tests20. The upper limit for incorporation of the bitter tastant n-PROP into edible films is considerably lower than for other tastants. This lower limit is a function of the solubility of n-PROP in aqueous solutions (6.5 mMolar in water at 20 °C). However, this amount is considerably above reported suprathreshold values for n-PROP22. Finally, taste modifiers such as lactisole23 can be readily incorporated into pullulan-based films.

TABLE I.

Summary of Taste Stimuli and Taste Modifiers that can be Incorporated into an Edible Taste Strip

| Tastant or Taste Modifier |

Percent Tastant (w/vol) |

Maximum Amount of Tastant in strip |

Drying Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | 5.0 | 77.9 uMoles | Room temperature |

| L-Ascorbic acid | 4.6 | 139.3 uMoles | Room temperature or 35° C |

| Sodium chloride | 4.25 | 387.9 uMoles | Room temperature |

| Quinine HCl | 2.5 | 36.9 uMoles | Room temperature |

| Monosodium glutamate | 4.25 | 134.0 uMoles | Room temperature |

| 6-propyl-2-thiouracil | 0.11 | 3.4 uMoles | Room temperature |

| *Sodium 2-(4-methoxy- phenoxy) propanoate |

> 2.0 | > 48.9 uMoles | Room temperature |

The values in column two represent the percentage of tastant in an aqueous solution that was used to prepare a clear taste film that is readily removed from its casting surface. Maximum amount of tastant in strip is the amount of tastant in a 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm strip where the taste strip was prepared from 533.3 uliters of polymer solution. All strips were composed of 3.25% polymer. Sodium 2-(4-methoxyphenoxy) propanoate is the taste modifier, lactisole.

Uniformity of tastant in pullulan-HPMC strips

Five 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm strips were assayed for total quinine content. After dissolving a single 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm control strip in the sample cuvette, a decrease in fluorescence emission of quinine was observed (7.1%), along with a one-nanometer shift of the maximum wavelength to 451 nanometers. After correcting for this polymer-induced decrease in fluorescence, the five strips contained on average 103.1 +/− 4.4 nmoles of quinine hydrochloride. This amount was 87.2 +/− 3.7% of the calculated value for quinine. These results demonstrate that tastant remained in the film during drying, and that edible strips contained uniform quinine content. These results further suggested that the actual amount of taste stimulus added to the polymer solution was near predicted values in the dried film.

Finally, control strips used in the sucrose taste recognition study yielded a response of no taste (no sweet, sour, salty, or bitter taste) 97.8% of the time (n = 539). These results demonstrate that pullulan-based edible taste strips have very little background taste when dissolved by saliva in the oral cavity.

The taste recognition data for edible strips that contained varying amounts of sucrose is presented in Figure 2. Figure 2A describes the distribution of test subjects when edible strips were used as the delivery method for recognition threshold measurements of sweet taste. A cumulative frequency distribution of taste recognition thresholds (cumulative thresholds) shown in Figure 2B, yielded a sigmoidal curve with an r2 value (for a sigmoidal curve) of 0.99 in our psychophysical model. The slope of the curve indicates the range over which our population of 32 subjects could detect a change in the amount of sucrose in taste strips. Overall, an average threshold recognition value of 3.3 micromoles was observed in our sample population (average age of 32.3 years). In addition, taste recognition thresholds for sucrose indicated that median values were slightly lower in women than in men. The median threshold value for women (n = 14) was 3.2 micromoles, and the median threshold value for men (n = 18) was 3.4 micromoles. In our sample, no significant difference between the two gender groups was found (P ≥ 0.05, two-tailed test). A large study that examines taste recognition thresholds as a function of sex and age in decades will allow a systematic examination of potential gender differences in taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste.

Fig. 2.

Human taste recognition thresholds for the sweet tastant sucrose that were obtained with edible taste strips. Various amounts of sucrose were incorporated into 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm edible taste strips. (A) Graph represents the number of subjects that could detect the tastant in strips containing differing amounts of sucrose. (B) Cumulative frequency distribution of taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste that was obtained with edible taste strips.

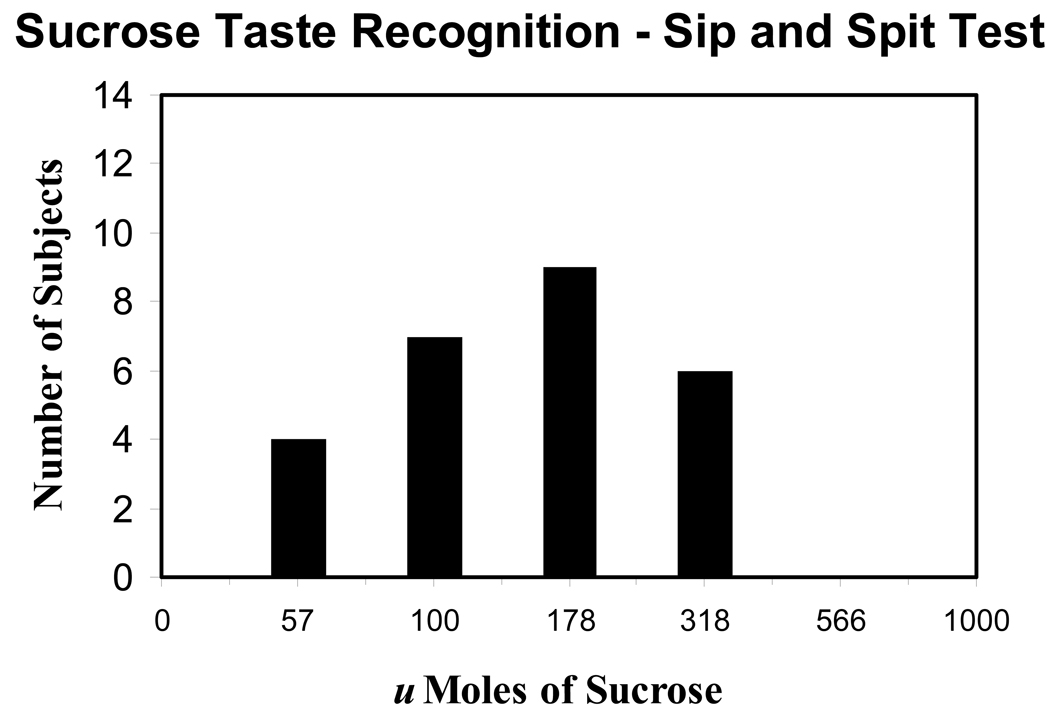

Sucrose taste recognition thresholds that were obtained from an aqueous “sip and spit” test are shown in Figure 3. For the liquid test, taste recognition thresholds for sucrose were considerably higher when compared to the results obtained with edible strips. The mean threshold value for sucrose recognition was 172.6 micromoles. The mean threshold value for women (n = 12) was 150.0 micromoles, and the mean threshold value for men was 190.6 micromoles (n = 15). In our sample (average age was 27.6 years), no significant difference between the two gender groups was observed (P ≥ 0.05, two-tailed test).

Fig. 3.

Human taste recognition thresholds for the sweet tastant sucrose that were obtained from a standard sip and spit test using a 10 mL sample volume. (A) Graph represents the number of subjects that could detect a tastant in solutions containing varying amounts of sucrose. (B) Cumulative frequency distribution of taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste that was obtained with an aqueous test.

Comparison of taste strips to an aqueous taste test

The mean taste recognition thresholds for sweet taste that were obtained from edible taste strips are over one order of magnitude lower than those reported with water-based testing protocols for comparable age groups24. In addition, the variability was considerably smaller when taste recognition thresholds were measured with edible taste strips. These results demonstrate that pullulan-HPMC taste strips are excellent substrates for delivery of tastant. Furthermore, these strips exhibit considerable sensitivity for examination of taste recognition thresholds in humans.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the utility of edible taste strips as a rapid method for presentation and detection of taste stimuli in humans. Based on commercially available strips for improving oral hygiene, these 2.54 cm × 2.54 cm strips are extremely useful substrates for measuring taste function both in clinical and in non-clinical settings. When placed in the mouth, these strips are rapidly dissolved by saliva, and release tastant into the oral cavity. In addition, these pullulan-HPMC films incorporate a broad range of taste stimuli during film formation. By varying the amount of tastant in strips, taste intensity responses for future suprathreshold studies for all major classes of taste stimuli should be feasible. Based on their ability to incorporate n-PROP, edible taste strips should be highly useful for examining specific taste ageusias to bitter-tasting compounds such a phenylthiocarbamide or n-PROP.

Because of their rapid dissolving time in the oral cavity, somatosensory cues from edible taste strips appear to be minimal. These taste strips possess a long shelf life, require little storage space, and are readily portable for testing outside the clinic, lab, or classroom. These easy-to-administer edible strips are odorless, non-allergenic, and require a short testing time. In addition, these strips can be prepared in a variety of shapes, thicknesses, and sizes. Preliminary studies with L-ascorbic acid indicate that little volatility of tastant occurs during dissolving time in the mouth so that this test should find use in separating potential olfactory components of gustation (unpublished data). If true for all classes of tastants, this method will be invaluable for separating the gustatory, olfactory, and trigeminal components of flavor.

One major advantage of taste strips is that a precise amount of tastant (or taste modifier) can be incorporated into a strip of specified size and thickness. The taste stimulus is released into a more localized area of the oral cavity because solubilization is dependent on the presence of saliva that comes in direct contact with the taste strip. Local saliva production is less than five milliliters under normal circumstances, and bulk movement of saliva in the oral cavity is considerably less than what would be expected from a 10–15 ml water volume during a traditional “sip and spit” test. Thus, the dissolved tastant that is released from strips will be more localized and more concentrated when compared to aqueous taste tests. This smaller volume likely caused or contributed to the significantly lower threshold recognition values for sucrose when compared to the aqueous "sip and spit" test because the aqueous test essentially “dilutes” the amount of tastant that is directly in contact with taste receptor cells on the tongue surface.

Because of their low background taste, edible taste strips are excellent vehicles for taste recognition threshold measurements. Edible taste strips are readily adapted for examination of thresholds by modification of the three-drop20, or a two-alternative staircase method25. In addition, this technique should be applicable for regional taste testing on the tongue surface by preparing small, circular taste strips with a paper hole punch. Film thickness can also be modified for examination of regional taste testing. Also, edible taste strips should be useful for simultaneous presentation of mixtures of tastants in the oral cavity. In addition, taste blockers such as lactisole23 or gymnemic acid extracts26 are readily incorporated into taste strips. Finally, edible taste strips can be rapidly dissolved in 10–15 ml of water for presentation of taste stimulus (or a taste modifier) as a standard water-based taste test in the clinic, or at a remote location.

CONCLUSIONS

The preparation and use of edible taste strips composed of pullulan and HPMC allows the rapid evaluation of taste recognition thresholds in humans. The concentration and ratio of pullulan-HPMC polymers, variation in film thickness and size, and incorporation of additives such as gum Arabic can modify the physical properties of taste strips for tailoring the strips to a variety of psychophysical protocols. An edible film-based taste test should have application to threshold studies, suprathreshold studies, regional taste testing, and studies on taste blindness. In summary, this test will make possible for the first time a mechanism for gathering large-scale epidemiological data on human gustatory function.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDCD R43 DC007291, R44 DC007291, and a Return of Overhead Research Incentive Grant from Temple University. Hetvi Desai and Si Lam are recipients of an undergraduate research award from Temple University. Dr. Hastings is a major shareholder in Osmic Enterprises, Inc., which is a manufacturer and distributor of products for measurements of chemosensory function. The authors thank Drs. Paul Moberg, Robert Frank, Harry P. Rappaport, and Richard L. Doty for valuable discussions and comments, Dr. Ellis Golub for use of the fluorometer, and Tuong-Vi Pham for valuable assistance. The authors also thank Dow Chemical Company for the gift of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, and Domino Foods Incorporated for the gift of lactisole. Finally, the authors wish to thank the subjects who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Hawkes CH. Anatomy and Physiology of Taste Sense. Amsterdam: Butterworth Heinmeann; 2002. Smell and Taste Complaints; pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Hayes JE, Moskowitz HR, Snyder DJ. Psychophysics of sweet and fat perception in obesity: problems, solutions and new perspectives. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1137–1148. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perl E, Shufman E, Vas A, Luger S, Steiner JE. Taste- and odor-reactivity in heroin addicts. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1997;34:290–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driscoll KA, Perez M, Cukrowicz KC, Butler M, Joiner TE., Jr Associations of phenylthiocarbamide tasting to alcohol problems and family history of alcoholism differ by gender. Psychiatry Res. 2006;143:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy VB, Davidson AC, Kidd JR, et al. Bitter receptor gene (TAS2R38), 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness and alcohol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1629–1637. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000145789.55183.D4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meiselman HL. Magnitude estimations of the course of gustatory adaptation. Percept Psychophys. 1968;4:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zald DH, Pardo JV. Cortical activation induced by intraoral stimulation with water in humans. Chem Senses. 2000;25:267–275. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartoshuk LM. Water taste in man. Percept Psychophys. 1968;3:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galindo-Cuspinera V, Winnig M, Bufe B, Meyerhof W, Breslin PAS. A TAS1R receptor-based explanation of sweet “water-taste.”. Nature. 2006;441:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimoto K, Hirota R, Egawa M, Furuta S. Clinical evaluation of taste dysfunction using a salt-impregnated taste strip. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996;58:258–261. doi: 10.1159/000276849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel T, Erras A, Kobal G. A test for the screening of taste function. Rhinology. 1997;35:146–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahne G, Erras A, Hummel T, Kobal G. Assessment of gustatory function by means of tasting tablets. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1396–1401. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200008000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller C, Kallert S, Renner B, et al. Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated “taste strips”. Rhinology. 2003;41:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flammer LJ, Sondrup J, Graniger B, Alvarez-Reeves M, Green B. Starch-based flavor films: A novel method for whole mouth stimulation with precise stimulus amounts. Chem Senses. 2003;28:A14. (abs). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kettenmann B, Mueller C, Willie C, Kobal G. Odor and taste interaction on brain responses in humans. Chem Senses. 2005;30(suppl 1):i234–i235. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawless HT. A comparison of different methods used to assess sensitivity to the taste of phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) Chem Senses. 1980;5:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leathers TD. Biotechnological production and applications of pullulan. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;62:468–473. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiyoshi T, Tanaka N, Nakamura T, Matzno S, Shinozuka K, Uchida T. Effects of quinine on the intracellular calcium level and membrane potential of PC 12 cultures. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007;59:1521–1526. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.11.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiffenbach JM, Wolf RO, Benheim AE, Folio CJ. Taste threshold assessment: a note on quality specific differences between methods. Chem Senses. 1983;8:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank ME, Hettinger TP, Barry MA, Gent JF, Doty RL. Contemporary Measurements of Human Gustatory Function. In: Doty RL, editor. Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation. 2nd edn. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2002. pp. 783–804. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty RL, McKeown DA, Lee WW, Shaman P. A study of the test-retest reliability of ten olfactory tests. Chem Senses. 1995;20:645–656. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Reed D, Williams A. Supertasting, earaches and head injury: Genetics and pathology alter our taste worlds. Neurosci & Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang P, Cui M, Zhao B, et al. Lactisole interacts with the transmembrane domains of human T1R3 to inhibit sweet taste. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15238–15246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong J-H, Chung J-W, Kim Y-K, Chung S-C, Lee S-W, Kho H-S. The relationship between PTC taster status and taste thresholds in young adults. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wetherill GB, Levitt H. Sequential estimation of points on a psychometric function. Br Jrl Math Stat Psychol. 1965;18:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1965.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gent JF, Hettinger TP, Frank ME, Marks LE. Taste confusions following gymnemic acid rinse. Chem Senses. 1999;24:393–403. doi: 10.1093/chemse/24.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]