Abstract

The cardiac interstitium is a unique and adaptable extracellular matrix (ECM) that provides a milieu in which myocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells communicate and function. The composition of the ECM in the heart includes structural proteins such as fibrillar collagens and matricellular proteins that modulate cell:ECM interaction. Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC), a collagen-binding matricellular protein, serves a key role in collagen assembly into the ECM. Recent results demonstrated increased cardiac rupture, dysfunction and mortality in SPARC-null mice in response to myocardial infarction that was associated with a decreased capacity to generate organized, mature collagen fibers. In response to pressure overload induced-hypertrophy, the decrease in insoluble collagen incorporation in the left ventricle of SPARC-null hearts was coincident with diminished ventricular stiffness in comparison to WT mice with pressure overload. This review will focus on the role of SPARC in the regulation of interstitial collagen during cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction and pressure overload with a discussion of potential cellular mechanisms that control SPARC-dependent collagen assembly in the heart.

Keywords: BM-40, osteonectin, SPARC, extracellular matrix, remodeling, review

Cardiac Interstitium

The cardiac interstitium is composed primarily of collagen type I with lesser amounts of collagens type III and type V contributing to the majority of cardiac connective tissue [1]. The collagenous ECM of the heart undergoes relatively high rates of turnover in comparison to collagen in the ECM of other collagen-rich tissues such as dermis and tendon [2]. For example in adult rabbits, the collagen fractional synthesis rate is 8.94% in the heart and 0.86% in the skin [3]. In addition, cardiac fibrillar collagen is more insoluble than collagen in other tissues, due to increases in myocardial cross-linking of the interstitial collagen network [4]. Collagen fibrils in the heart are incorporated into characteristic structures identified as weaves, coils, and struts [5]. Presumably, each type of structure serves a distinct function in maintaining efficiency of myocyte contraction [6]. In response to pressure overload hypertrophy and in the myocardial infarcted zone, collagen fibers increase in both size and number [1].

Mechanisms that govern assembly and regulate structure of each type of distinct collagen fiber have not been well defined but likely include incorporation of specific proteoglycan and glycosaminoglycan collagen-binding partners. For example, small leucine rich proteoglycans (SLRPs), such as lumican and biglycan, have been shown to regulate collagen fibril diameters in tendon and have been implicated in cardiac ECM remodeling [7, 8]. Notably, levels of lumican expression in heart tissue was rivaled only by levels of expression in the cornea [8]. In addition, incorporation of other collagen types such as the ratio of collagen I to collagen III or association of Fibril Associated Collagens with Interrupted Triple Helical domains (FACIT) collagens such as collagen types XII and XIV, represent potential factors contributing to collagen fibril organization in the heart [9]. Matricellular proteins, such as SPARC (osteonectin, BM-40), are another class of factors that are known to influence collagen fibril assembly and morphology [10]. Studies to evaluate the function of SPARC and other matricellular proteins in heart diseases have revealed critical activities of this class of proteins in cardiac physiology and disease [11–15].

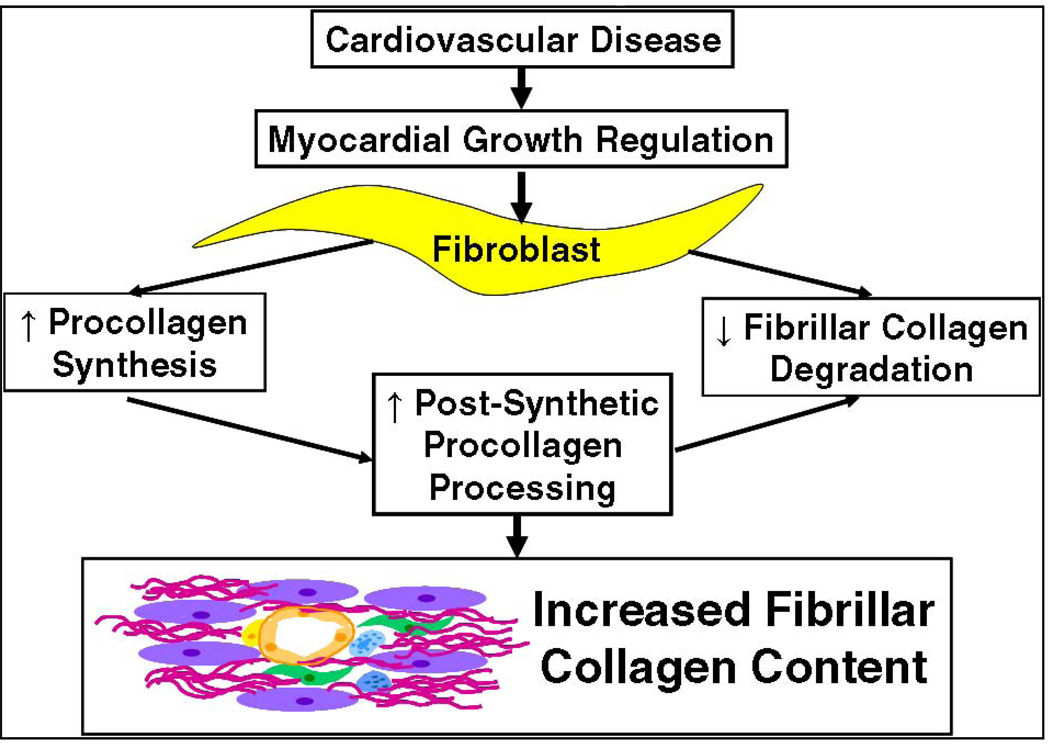

Transcriptional regulation of procollagen I and degradation of collagen fibers by collagenases of the MMP family are two well-studied examples of cellular mechanisms that influence levels of collagen accumulation in tissues. Evidence suggests that SPARC acts at a third point of regulation, namely post-synthetic procollagen processing and assembly of collagen into fibrils (Fig. 1). Recently, two studies were published on the role of SPARC in collagen remodeling in response to myocardial infarction (MI) and pressure overload - two animal models that involve extensive reorganization of the cardiac ECM accompanied by fibrotic deposition of collagen. Results from these studies have demonstrated a necessary role for SPARC in assembly of insoluble fibrillar collagen in the cardiac interstitium. In this review, we will give a brief summary of activities of SPARC primarily based on studies from non-cardiac tissues. We will then review relevant analyses of fibrillar collagen expression and deposition in response to both pressure overload and MI to highlight expression patterns of SPARC in the context of fibrillar collagen production. Finally, the effects of abrogated SPARC expression in these two animal models of heart disease will be evaluated in terms of the influence of SPARC in procollagen post-synthetic processing as a potential cellular mechanism that governs collagen deposition.

Figure 1.

Regulatory mechanisms controlling collagen homeostasis. This review will focus on the proposed function of SPARC in post-synthetic procollagen processing to influence collagen deposition in the heart.

SPARC

SPARC is a prototypic matricellular protein made up of three modular domains [16]. Other matricellular proteins include, the SPARC family member hevin (SC1), thrombospondins 1 and 2, tenascins C and X, periostin, the CCN family, and osteopontin [13]. Matricellular proteins are defined as proteins that do not contribute to the ECM structurally but serve accessory roles to regulate cell - ECM interactions such as, signaling, adhesion, proliferation, migration, and survival [10]. Of the three modular domains of SPARC, the first is a 53 amino acid domain that contains a 17 residue N-terminal secretory signal peptide and two clusters of Glu residues that bind to calcium ions. The second domain is composed of two sub-domains made up of a 24 amino acid follistatin-like domain and a 55 amino acid protease-like inhibitor region. The third domain, a 151 amino acid extracellular high-affinity calcium-binding region known as the EC domain, contains the collagen-binding region.

That SPARC is conserved in a wide variety of evolutionarily diverse organisms (e.g., C. elegans, Drosophila, brine shrimp, trout, chicken, mice, and humans), suggests a basic function of SPARC in multicellular biology [16]. In vitro, SPARC induces cell rounding in a number of cell types and thus has been designated a counter-adhesive protein. The capacity of SPARC to bind fibrillar collagens such as types I, III, and V as well as type IV implicates SPARC in the regulation of ECM assembly in both connective tissue (rich in fibrillar collagens I, III, and V) and basal laminae (where collagen IV is a prominent component) [16, 17].

SPARC expression is high in many developing tissues including embryonic heart. However, upon organ maturation, levels of SPARC decrease and remain relatively low in normal hearts and in most adult tissues with the exception of those that undergo high rates of ECM turnover such as bone and gut epithelia [16]. Upon injury, particularly those associated with excessive deposition of collagen, there is robust re-expression of SPARC. Hence, expression patterns of SPARC are consistent with a critical role of this protein in collagen production and deposition. Accordingly, inhibition of SPARC production by adenoviral delivery of anti-sense SPARC in vivo, in a rat model of liver fibrosis, resulted in significantly decreased tissue concentrations of collagen [18].

SPARC-null mice display a range of phenotypes, the basis of which appears to reside primarily in alterations in ECM organization. For example, the skin of SPARC-null mice displayed substantial aberrations in both structure and composition of the collagen–rich dermis. The collagen content of adult SPARC-null skin was approximately half that of wild-type (WT) and, notably, the SPARC-null collagen fibers in the skin were reduced in terms of collagen maturation, in comparison to those of WT mice [19]. In addition, transmission electron microscopy revealed smaller collagen fibrils in the absence of SPARC that were more uniform in size than WT fibrils [19]. A decrease in collagen deposition was also reported in bleomycin-induced injury in the lungs of SPARC-null mice and, in an animal model of hypertension, diminished fibrosis in the kidney of SPARC-null versus WT mice was observed [20, 21].

The hearts of SPARC-null mice at 3 months of age contain significantly less fibrillar collagen in comparison to WT mice as assessed by hydroxyproline and collagen volume fraction analysis [11]. In picrosiruis red-stained sections, SPARC-null collagen fibers were less frequent and less mature than those of WT mice. Images taken using scanning electron microscopy showed smaller collagen fibrils that were fewer in number in SPARC-null versus WT hearts. Thus, SPARC is a primary mediator of collagen ECM assembly and stability in a variety of tissues including the heart.

Increases in SPARC expression were also noted in cardiac pathologies associated with increased collagen deposition. For example, SPARC expression was found to increase in the hearts of rats subjected to β-adrenergic stimulation coincident with increases in collagen types I and III, in addition to increases in TGF-β1 [22]. TGF-β1 is a potent mediator of ECM deposition and is implicated in cardiac myofibroblast conversion. The capacity of SPARC to influence TGF-β1 signal transduction and myofibroblast differentiation will be discussed further below. In human heart disease, SPARC expression was found to be elevated in tissue sections from ventricles of individuals with left ventricular hypertrophy in one study [23]. More extensive characterization of SPARC in human heart disease will be an important and primary focus of future studies.

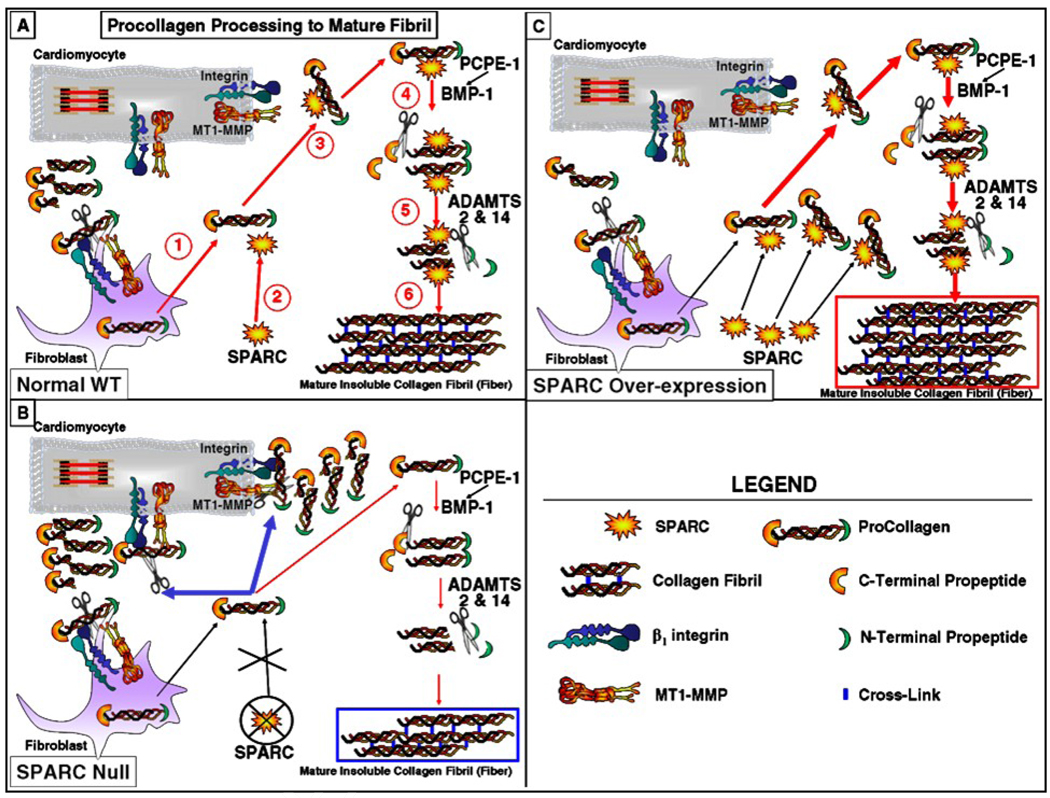

While transcriptional regulation of collagen mRNA represents one mechanism by which levels of collagen synthesis is controlled, a significant amount of collagen protein is degraded prior to deposition into the cardiac ECM, representing a level of post-translational regulation of collagen influencing ECM deposition in the heart [3]. Although degradation of procollagen is known to occur in other tissues, the level to which this mechanism is used by cardiac fibroblasts is particularly impressive. 90% of newly synthesized procollagen was shown to be degraded rapidly, prior to ECM incorporation [3]. Hence, post-synthetic regulation of procollagen I, that includes processing of procollagen to collagen I by removal of N- and C-terminal propeptides, plays a prominent role controlling amounts of collagen assembled into ECM fibers (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Model of Proposed Function of SPARC in Post-synthetic Procollagen Processing.

Panel A: Procollagen processing into a mature collagen fibril in normal wild type (WT) mouse myocardium: 1. Procollagen secreted into the extracellular space. 2. SPARC binds to procollagen (or procollagen is secreted bound by SPARC). 3. SPARC decreases collagen association with cell surface receptors (or a subset of receptors). 4. C-terminal propeptide of procollagen cleaved by BMP-1 (enhanced by PCPE activity e.g. PCPE-1, PCPE-2, and Srfp2), 5. N-terminal propeptide cleaved by ADAMTS-2/14, 6. Collagen stabilized in mature fibrils by formation of cross-links.

Panel B: SPARC deletion alters the balance between processing to mature collagen fibrils and degradation; increased cell-associated collagen is degraded and/or taken up by cell-surface collagen receptors resulting in less procollagen effectively processed into mature fibrils and decreased levels of interstitial collagen assembled into insoluble fibers.

Panel C: SPARC over-expression further diminishes cell-associated collagen and promotes efficient procollagen processing and incorporation of collagen into fibrils thus enhancing deposition of collagen and formation of mature fibers.

SPARC: Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine, BMP: Bone Morphogenetic Protein, PCPE: Procollagen C-Proteinase Enhancer 1, other enhancers of activity include PCPE-2 and Srfp2. ADAMTS: A Disintegrin-like and Metalloproteinase Domain with Thrombospondin Type Motif, MT1-MMP: Membrane-Type Matrix Metalloproteinase.

Myocardial Infarction (MI)

The response to MI generates specific zones within the myocardium each with distinct cellular environments. For example, the area of infarct (infarct zone), the primary site of collagen deposition, has been shown to form subsequent to initial formation of a provisional matrix generated from extravasation of plasma proteins such as fibrin and fibronectin. The border zone, defined as the area adjacent to the infarct zone, separates the infarct zone from the remote region in which the myocardium retains its structural organization. Infiltration of macrophages that express a number of different cytokines and growth factors stimulate collagen production in and around the infarct zone [24]. Collagen produced primarily by fibroblasts, many of which display protein expression patterns characteristic of myofibroblast differentiation, is the primary constituent of the fibrous scar that preserves ventricular integrity and prevents cardiac rupture [25]. Myofibroblasts are characterized by expression of α-smooth muscle actin, a highly contractile phenotype, and an increased capacity to produce collagen in comparison to fibroblasts [26].

Expression of SPARC by cells associated within the infarct zone was shown to closely parallel that of collagens I and III. In a canine model, organized collagen fibrils were evident in the infarct at 7 days and collagen volume fraction taken from picrosirius red-stained tissue sections continued to rise peaking at 14 days. Quantification of SPARC immunopositive cells found that the number of positive cells was significantly elevated at day 7 and reached a peak at day 14 in dogs [27]. Collagen deposition was detectable at earlier times in mice where significant collagen accumulation was found 3 days following infarct [27]. Similarly, the number of SPARC immunopositive cells after infarct was found to be significantly increased at day 3 and was diminished but remained significantly higher than control at day 7 in mice [27]. Wu et al. found that SPARC mRNA increased ~2.6 fold at day 2 following MI and peaked at ~3.7 fold by day 7 in mice [28]. Hence, expression of SPARC follows closely that of fibrillar collagen. The temporal differences in production of SPARC observed in dogs versus mice are coincident with differences in collagen deposition in the two species [27].

Schellings and colleagues recently presented an independent analysis of SPARC expression post MI and showed that SPARC levels demonstrated a moderate, ~ 2 fold increase from baseline in the remote and infarcted zone as assessed by quantification of protein levels by immunoblot analysis. At days 7 and 14 post-MI, levels of SPARC were substantially increased in the infarcted zone whereas significant increases over base line in the remote zone were not detected [12]. SPARC expression was primarily associated with α-smooth muscle cell positive myofibroblasts and CD45 positive leukocytes [12].

As mentioned previously, the absence of SPARC resulted in significant increases in myocardial rupture and ventricular dysfunction following MI [12]. Although significant differences in levels of mRNA encoding collagen types I and III were not detected in SPARC-null versus WT infarcts, the collagen fibers were disorganized and immature in the absence of SPARC expression. Transmission electron microscopy revealed quantitatively smaller collagen fibril diameters in the SPARC-null infarcts versus those of WT mice, similar to previously reported abnormalities in SPARC-null dermal collagen fibrils [12, 19]. These results were consistent with SPARC being an essential component in the post-synthetic processing and assembly of collagen fibrils.

Importantly, over-expression of SPARC by adenoviral delivery in WT mice 2 days prior to MI, confirmed by elevated levels of SPARC in plasma, resulted in improved cardiac function and a reduction in dilation without significant effects on infarct size [12]. Thus, adenoviral-mediated over-expression of SPARC, in addition to enhanced endogenous levels of SPARC associated with MI, was beneficial in preserving cardiac function after injury.

Schellings et al. went on to assess SPARC-dependent activity in terms of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 signal transduction. Previously, SPARC was implicated in the regulation of TGF-β1 signaling in other cell types in vitro, for example, in primary kidney mesangial cells and in epithelial cells [29, 30]. Infarcts from WT mice with elevated SPARC expression exhibited increased levels of phosphorylated Smad2, a down-stream element in the TGF-β1 signaling cascade. Although inhibition of SPARC expression by shRNA in fibroblasts decreased the ratio of p-Smad2/Smad 2 following TGF-β1 stimulation, SPARC-null versus WT infarcts did not demonstrate significant differences in Smad2 activation in vivo. Nonetheless, infusion of TGF-β1 by mini-pump following MI resulted in significant diminution of cardiac rupture in SPARC-null mice and increased deposition of mature, collagen fibers [12]. Hence, these studies are in line with previous results that suggest SPARC augments the activity of TGF-β1 under some conditions through an, as yet, undefined mechanism.

Interestingly, SPARC-null infarcts exhibited significantly more myofibroblasts than WT infarcts [12]. As TGF-β1 is a potent activator of myofibroblast conversion, the opposite might have been predicted, a decrease in the number of myofibroblasts in SPARC-null infarcts due to decreased potency of TGF-β1. However, in accord with these results, Chlenksi et al. reported that SPARC blocked myofibroblast activation in NIH 3T3 and primary fibroblasts [31]. Hence, the function of SPARC in modulating the activity of TGF-β1 signal transduction pathways, such as Smad2 phosphorylation versus myofibroblast conversion, might indicate the existence of distinct TGF-β1-dependent pathways in resident cardiac fibroblasts, or perhaps in fibroblasts originating from circulating stem cells, that control myofibroblast differentiation. For example, mechanisms involving α3β1 integrin and hyaluronan in either myofibroblast conversion or maintenance, respectively, were recently shown to be independent of Smad2 phosphorylation [32, 33]. In addition, the prediction that increases in the number of myofibroblasts should increase levels of collagen deposition was also not true in SPARC-null infarcts indicating that increased myofibroblast differentiation alone was not sufficient to drive increased incorporation of mature collagen.

Pressure Overload Cardiac Hypertrophy

Animal models of pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy mimic certain types of human heart disease, such as hypertension and valvular aortic stenosis, characterized by, among other features, fibrotic deposition of collagen [34]. Chapman et al. reported that supra-renal abdominal artery banding in rats, for example, gave rise to increases in mRNA encoding collagen types I and III at day 3 following banding [35]. Similar increases in collagen types I and III mRNA were reported by Villarreal and Dillman who also reported increased levels of mRNA encoding TGF-β1 shortly following banding [36]. TGF-β1 is a potent inducer of collagen mRNA and a known mediator of myofibroblast conversion. Interestingly, Kuwahara et al. showed that TGF-β1 neutralizing antibodies injected intraperitoneally, inhibited differentiation of myofibroblasts and myocardial fibrosis in this rat model of pressure overload [37].

Banding of the aorta in mice (transverse aortic constriction, TAC) gave rise to increased expression of mRNA encoding collagen types I and III at day 3 [38]. Similar to rats, collagen type III mRNA demonstrated greater induction versus that of collagen I [37, 38]. Results from multiple studies have shown that significant collagen accumulation, primarily evaluated by measurements of collagen volume fraction, was apparent in left ventricles 4 to 5 weeks following banding [11].

The influence of SPARC on collagen deposition in response to pressure overload hypertrophy was recently assessed [11]. Similar to MI, the fibrotic response to pressure overload is muted in the absence of SPARC. Upon incorporation into the insoluble ECM, collagen protein is stabilized by the formation of covalent cross-links [4]. Increases in the level of insoluble versus soluble collagen, as an indirect measure of collagen cross-links, have been reported in response to pressure overload and have been shown to contribute to increases in ventricular stiffness [39]. At 4 weeks following TAC in WT mice, levels of insoluble collagen increased whereas soluble collagen decreased [11]. Papillary muscle isolated from WT TAC mice demonstrated increases in muscle stiffness associated with increased insoluble collagen content versus control WT mice. In contrast, trans-aortic banding (TAC) in SPARC-null mice resulted in lesser amounts of insoluble collagen deposited in the interstitium accompanied by greater amounts of soluble collagen in comparison to age-matched WT TAC mice [11]. In the absence of SPARC, the decrease in insoluble collagen concentrations was associated with decreased muscle stiffness both in SPARC-null versus WT control and in SPARC-null versus WT TAC mice [11].

Similar to MI, where the absence of SPARC did not influence collagen synthesis, total cardiac collagen concentrations in hypertrophied ventricles of SPARC-null TAC mice were not significantly different than total collagen concentrations in hypertrophic ventricles from WT TAC hearts as measured by hydroxyproline analysis. The primary effect of the loss of SPARC was the increase in soluble collagen at the expense of insoluble collagen incorporation and suggested an inefficiency of collagen incorporation into fibrils in the absence of SPARC.

Cellular Basis of SPARC Activity

Results from both MI and pressure overload studies implicate SPARC in the regulation of post-synthetic processing of collagen prior to deposition in the cardiac ECM rather than in transcriptional control of collagen synthesis. In Rentz et al., studies using dermal fibroblasts suggested that in the absence of SPARC, collagen I was not efficiently deposited into an insoluble ECM by virtue of increased cell association of collagen I most likely via increased interactions with cell surface receptors [40]. In this scenario, collagen I bound by SPARC is predicted to diminish collagen I association with cells, in line with previously characterized counter-adhesive activities of SPARC. In the absence of SPARC expression, then, collagen I engagement or tethering to cell surfaces favors turnover of collagen I, perhaps by phagocytosis or degradation by cell surface-associated collagenases, rather than ECM incorporation (Fig. 2) [41, 42]. In the case of SPARC-over-expression, SPARC might further limit collagen association with cell surfaces enhancing collagen deposition and formation of mature, insoluble collagen fibers (Fig. 2).

Also noted in these fibroblast studies was an increase in the proportion of total collagen I in SPARC-null cell layers with both propeptides removed versus that of WT cells [40]. Procollagen is produced with N- and C-terminal propeptides that are cleaved to generate fibril-forming collagen I monomers. Thus, a function of SPARC in the regulation of procollagen post-synthetic processing was proposed. The decrease in insoluble collagen incorporation in SPARC-null TAC mice accompanied by increased levels of soluble collagen was consistent with a mechanism in which SPARC facilitated collagen processing and subsequent incorporation into the cardiac ECM. Secreted Frizzled-related protein (sFRP) 2, a procollagen C-proteinase enhancer is a protein that augments procollagen processing by increasing the activity of procollagen C-terminal proteinases, BMP-1 [43]. Kobyashi et al. showed that mice lacking sFRP2 exhibited a reduced fibrotic response to MI [43]. These results are representative of the importance of procollagen processing and subsequent collagen incorporation into ECM as essential points of regulation in fibrotic collagen deposition in the heart.

Furthermore, in a rabbit model of pressure overload, Bishop et al. showed that, in addition to increases in mRNA encoding collagen I, decreases in the amount of collagen degraded prior to ECM assembly occurred 2 days following induction of pressure overload and persisted out to 14 days [44]. This decrease in degradation is predicted to contribute to overall increases in ventricular collagen concentrations in pressure-overloaded myocardium [44]. These results highlight the importance of post-synthetic procollagen processing as a point of regulation used by cardiac fibroblasts to control collagen deposition, a point of regulation predicted to be facilitated by SPARC expression.

Somewhat surprisingly, in the analysis of both MI and pressure-overload, differences in the blood vessel function and density were not significantly altered by the absence of SPARC. SPARC was originally identified in conditioned media of endothelial cells as a secreted protein in high abundance [45]. Although many studies characterizing the functions of SPARC have been carried out in endothelial cells in vitro, analysis of SPARC-null mice have not revealed a significant vascular phenotype in most tissues examined in these mice to date.

Expression of SPARC by cardiac myocytes has been shown in early development and in cultured cells [46, 47]. To test whether the absence of SPARC effects cardiac myocyte contractility in adult mice, individual cardiac myocytes from SPARC-null and WT animals were evaluated in terms of systolic and diastolic function [11]. No differences in percent or rates of cell shortening nor in rate of lengthening or stiffness were detected in SPARC-null versus WT cells [11]. Although a functional role of SPARC in myocytes cannot be ruled out, evidence to date supports a more prominent activity of SPARC in influencing the cardiac interstitium.

In contrast to animal models of MI, in which a provisional matrix is formed in response to significant myocyte death, the same is not observed in response to pressure overload hypertrophy. However, perivascular fibrosis accompanied by markers of inflammatory cells has been shown in animal models of pressure overload at early times following banding [48]. Thus, inflammatory mediators might also contribute to initial deposition of collagen in animal models of pressure-overloaded myocardium. Schellings et al. reported that leukocyte infiltration was not significantly different in SPARC-null versus WT mice with the exception of the 14 day time point at which fewer leukocytes were found in SPARC-null infarcts [12]. An altered immune response in SPARC-null mice has been reported by Rempel et al. characterized by alterations in the cellular organization of the spleen and a decreased immune response to lipopolysaccharide challenge [49]. Macrophages express both SPARC and a SPARC-binding cell surface receptor, stabilin-1, that presumably clears SPARC from the extracellular milieu [50]. Hence, macrophages might be instrumental in controlling levels of extracellular SPARC in vivo. Because differences in leukocyte infiltration were only evident at later times following MI, it is unlikely that lack of SPARC expression by leukocytes in SPARC-null mice was the primary mechanism underlying disorganized collagen deposition in response to MI as increases in collagen synthesis and deposition occur by day 3 in this model.

Conclusions

Future experiments to further characterize the mechanisms of SPARC activity in the cardiac interstitium should include fibroblast-specific over-expression and abrogated expression of SPARC. These studies will determine whether SPARC must be co-expressed with collagen I in the same cell to effect collagen deposition or whether extracellular SPARC secreted by other cell types might provide sufficient activity to facilitate collagen deposition. In additions, expression of mutant forms of SPARC that do not bind collagen should be tested to decipher whether collagen-binding activity of SPARC is required to elicit changes in collagen assembly as would be predicted in the present model (Fig. 2). As SPARC is produced by C. elegans and Drosophila, organism that lack collagen I, also of interest is whether SPARC serves a similar function in basal lamina assembly through interaction with collagen IV.

Fibrillar collagens serve a critical role in the heart to support form and function of this vital organ. As increased cardiac collagen concentrations in the human population are associated with certain types of heart disease, notably diastolic heart failure, the necessity to identify factors indicative of increased collagen deposition in the heart as biological markers is an active area of research [34, 51]. Furthermore, the characterization of protein activities that enhance cardiac fibrosis provide new avenues for the design of potential therapeutic agents to relieve the physiological effects of increased ventricular collagen content. A number of proteins in addition to SPARC are likely involved in procollagen maturation in the heart including C- and N-terminal procollagen proteinases, enhancers of proteinases, and other matricellular proteins. However, the SPARC-null mouse serves as a reminder that a diminished capacity to mount a fibrotic response in the heart results in a negative outcome to infarction. Hence, the regulation of cardiac collagen deposition must be a finely tuned and adaptable system to allow an organism to survive cardiac pathologies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Undergraduate Student Summer Research Fellowship from the American Physiological Society (SM), Netherlands Heart Foundation (2005B082, 2007B036, 2008B011), Ingenious Hypercare NoE from the European Union (EST 2005-020706-2), a VIDI grant of the Dutch Scientific Organisation (NWO) to (SH), and a Merit Award from the Veteran’s Administration (ADB), and P20RR017696 from the NIDCR, NIH (CFB, ADB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eghbali M, Weber KT. Collagen and the myocardium: fibrillar structure, biosynthesis and degradation in relation to hypertrophy and its regression. Mol Cell Biochem. 1990;96:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00228448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop JE, Laurent GJ. Collagen turnover and its regulation in the normal and hypertrophying heart. Eur Heart J. 1995;16 Suppl C:38–44. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_c.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mays PK, McAnulty RJ, Campa JS, Laurent GJ. Age-related changes in collagen synthesis and degradation in rat tissues. Importance of degradation of newly synthesized collagen in regulating collagen production. Biochem J. 1991;276:307–313. doi: 10.1042/bj2760307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medugorac I. Collagen type distribution in the mammalian left ventricle during growth and aging. Res Exp Med (Berl. 1982;180:255–262. doi: 10.1007/BF01852298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borg TK, Sullivan T, Ivy J. Functional arrangement of connective tissue in striated muscle with emphasis on cardiac muscle. Scan Electron Microsc. 1982;(Pt 4):1775–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caulfield JB, Borg TK. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest. 1979;40:364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bereczki E, Santha M. The role of biglycan in the heart. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:129–132. doi: 10.1080/03008200802148504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying S, Shiraishi A, Kao CW, Converse RL, Funderburgh JL, Swiergiel J, et al. Characterization and expression of the mouse lumican gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30306–30313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Rest M, Garrone R. Collagen family of proteins. Faseb J. 1991;5:2814–2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornstein P, Sage EH. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:608–616. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Boggs J, Lacy JM, et al. Pressure overload-induced alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Circulation. 2009;119:269–280. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.773424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schellings MW, Vanhoutte D, Swinnen M, Cleutjens JP, Debets J, van Leeuwen RE, et al. Absence of SPARC results in increased cardiac rupture and dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2009;206:113–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schellings MW, Pinto YM, Heymans S. Matricellular proteins in the heart: possible role during stress and remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroen B, Heymans S, Sharma U, Blankesteijn WM, Pokharel S, Cleutjens JP, et al. Thrombospondin-2 is essential for myocardial matrix integrity: increased expression identifies failure-prone cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;95:515–522. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141019.20332.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimazaki M, Nakamura K, Kii I, Kashima T, Amizuka N, Li M, et al. Periostin is essential for cardiac healing after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2008;205:295–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradshaw AD, Sage EH. SPARC, a matricellular protein that functions in cellular differentiation and tissue response to injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1049–1054. doi: 10.1172/JCI12939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giudici C, Raynal N, Wiedemann H, Cabral WA, Marini JC, Timpl R, et al. Mapping of SPARC/BM-40/osteonectin-binding sites on fibrillar collagens. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19551–19560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camino AM, Atorrasagasti C, Maccio D, Prada F, Salvatierra E, Rizzo M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated inhibition of SPARC attenuates liver fibrosis in rats. J Gene Med. 2008;10:993–1004. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw AD, Puolakkainen P, Dasgupta J, Davidson JM, Wight TN, Sage EH. SPARC-null mice display abnormalities in the dermis characterized by decreased collagen fibril diameter and reduced tensile strength. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:949–955. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Socha MJ, Manhiani M, Said N, Imig JD, Motamed K. Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine Deficiency Ameliorates Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis in Angiotensin Hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1104–1112. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strandjord TP, Madtes DK, Weiss DJ, Sage EH. Collagen accumulation is decreased in SPARC-null mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L628–L635. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masson S, Arosio B, Luvara G, Gagliano N, Fiordaliso F, Santambrogio D, et al. Remodelling of cardiac extracellular matrix during beta-adrenergic stimulation: upregulation of SPARC in the myocardium of adult rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1505–1514. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridinger H, Rutenberg C, Lutz D, Buness A, Petersen I, Amann K, et al. Expression and tissue localization of beta-catenin, alpha-actinin and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 6 is modulated during rat and human left ventricular hypertrophy. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;86:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsey ML, Mann DL, Entman ML, Spinale FG. Extracellular matrix remodeling following myocardial injury. Ann Med. 2003;35:316–326. doi: 10.1080/07853890310001285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleutjens JP, Verluyten MJ, Smiths JF, Daemen MJ. Collagen remodeling after myocardial infarction in the rat heart. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:325–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Zymek P, Ren G, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. Extracellular matrix remodeling in canine and mouse myocardial infarcts. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:475–488. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu RX, Laser M, Han H, Varadarajulu J, Schuh K, Hallhuber M, et al. Fibroblast migration after myocardial infarction is regulated by transient SPARC expression. J Mol Med. 2006;84:241–252. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francki A, Bradshaw AD, Bassuk JA, Howe CC, Couser WG, Sage EH. SPARC regulates the expression of collagen type I and transforming growth factor-beta1 in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32145–32152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiemann BJ, Neil JR, Schiemann WP. SPARC inhibits epithelial cell proliferation in part through stimulation of the transforming growth factor-beta-signaling system. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3977–3988. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chlenski A, Guerrero LJ, Yang Q, Tian Y, Peddinti R, Salwen HR, et al. SPARC enhances tumor stroma formation and prevents fibroblast activation. Oncogene. 2007;26:4513–4522. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KK, Wei Y, Szekeres C, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Hill ML, et al. Epithelial cell alpha3beta1 integrin links beta-catenin and Smad signaling to promote myofibroblast formation and pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:213–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI36940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webber J, Meran S, Steadman R, Phillips A. Hyaluronan Orchestrates Transforming Growth Factor-{beta}1-dependent Maintenance of Myofibroblast Phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9083–9092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806989200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaasch WH, Zile MR. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:373–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.104417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman D, Weber KT, Eghbali M. Regulation of fibrillar collagen types I and III and basement membrane type IV collagen gene expression in pressure overloaded rat myocardium. Circ Res. 1990;67:787–794. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villarreal FJ, Dillmann WH. Cardiac hypertrophy-induced changes in mRNA levels for TGF-beta 1, fibronectin, and collagen. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1861–H1866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Kai M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta function blocking prevents myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overloaded rats. Circulation. 2002;106:130–135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020689.12472.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang D, Oparil S, Feng JA, Li P, Perry G, Chen LB, et al. Effects of pressure overload on extracellular matrix expression in the heart of the atrial natriuretic peptide-null mouse. Hypertension. 2003;42:88–95. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000074905.22908.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badenhorst D, Maseko M, Tsotetsi OJ, Naidoo A, Brooksbank R, Norton GR, et al. Cross-linking influences the impact of quantitative changes in myocardial collagen on cardiac stiffness and remodelling in hypertension in rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:632–641. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rentz TJ, Poobalarahi F, Bornstein P, Sage EH, Bradshaw AD. SPARC regulates processing of procollagen I and collagen fibrillogenesis in dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22062–22071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H, Overall CM, McCulloch CA, Sodek J. A Critical Role for MT1-MMP in Collagen Phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4812–4826. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee W, Sodek J, McCulloch CA. Role of integrins in regulation of collagen phagocytosis by human fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168:695–704. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199609)168:3<695::AID-JCP22>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi K, Luo M, Zhang Y, Wilkes DC, Ge G, Grieskamp T, et al. Secreted Frizzled-related protein 2 is a procollagen C proteinase enhancer with a role in fibrosis associated with myocardial infarction. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:46–55. doi: 10.1038/ncb1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bishop JE, Rhodes S, Laurent GJ, Low RB, Stirewalt WS. Increased collagen synthesis and decreased collagen degradation in right ventricular hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1581–1585. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes RC, Taylor A, Sage H, Hogan BL. Distinct patterns of glycosylation of colligin, a collagen-binding glycoprotein, and SPARC (osteonectin), a secreted Ca2+binding glycoprotein. Evidence for the localisation of colligin in the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Biochem. 1987;163:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H, Huang XN, Stewart AF, Sepulveda JL. Gene expression changes associated with fibronectin-induced cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:273–283. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00104.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engelmann GL. Coordinate gene expression during neonatal rat heart development. A possible role for the myocyte in extracellular matrix biogenesis and capillary angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1598–1605. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia Y, Lee K, Li N, Corbett D, Mendoza L, Frangogiannis NG. Characterization of the inflammatory and fibrotic response in a mouse model of cardiac pressure overload. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:471–481. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rempel SA, Hawley RC, Gutierrez JA, Mouzon E, Bobbitt KR, Lemke N, et al. Splenic and immune alterations of the Sparc-null mouse accompany a lack of immune response. Genes Immun. 2007;8:262–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kzhyshkowska J, Workman G, Cardo-Vila M, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Gratchev A, et al. Novel function of alternatively activated macrophages: stabilin-1-mediated clearance of SPARC. J Immunol. 2006;176:5825–5832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure--abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]