Abstract

Cleft palate is a common birth defect in humans and is a common phenotype associated with syndromic mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2). Cleft palate occurred in nearly all mice homozygous for the Crouzon syndrome mutation C342Y in the mesenchymal splice form of Fgfr2. Mutant embryos showed delayed palate elevation, stage-specific biphasic changes in palate mesenchymal proliferation, and reduced levels of mesenchymal glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Reduced levels of feedback regulators of FGF signaling suggest that this gain-of-function mutation in FGFR2 ultimately resembles loss of FGF function in palate mesenchyme. Knowledge of how mesenchymal FGF signaling regulates palatal shelf development may ultimately lead to pharmacological approaches to reduce cleft palate incidence in genetically predisposed humans.

Keywords: Crouzon syndrome, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2, cell proliferation, cell surface receptor, glycosaminoglycan

Craniosynostosis syndromes, as well as syndromic and nonsyndromic cleft palate, have been associated with fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) mutations. Of the four highly conserved FGFRs, FGFR2 is the most commonly mutated FGF receptor (1 –4). The FGF-FGFR family is involved in multiple intracellular signaling mechanisms in embryonic development, cell growth, wound healing, and tumorigenesis. The FGFRs are receptor tyrosine kinases that signal via a ternary complex of FGFR, FGF, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (5). The ternary complex formation leads to receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation, and activation of downstream signaling cascades (6).

FGF-FGFR signaling is active during palatogenesis, and genetic FGF mutations may contribute to 5% of cases of nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate (7). In children with isolated cleft palate, mutations in Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, and Fgf8 have been identified. Additionally, single nucleotide polymorphisms in children with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate are associated with Fgf3, Fgf7, Fgf10, Fgf18, and Fgfr1, providing confirmation of the importance of the FGF-FGFR system in palate development (7). Knockout mouse models for Fgf10 and Fgfr2b develop cleft palate (8, 9), establishing the necessity of epithelial FGF signaling in normal palatogenesis. Cleft palate in Fgf18−/− mice (10) suggests that mesenchymal FGF signaling may also be important for palate development.

Cleft palate has been associated with both gain-of-function and loss-of-function FGFR mutations (7, 11 –15). Why gain-of-function or loss-of-function mutations result in the same palatal phenotype remains unclear, and understanding this phenomenon may provide additional insight into the pathogenesis of cleft palate. To address this question, we have focused on Crouzon syndrome (CS), a disorder resulting from a missense Fgfr2 mutation that displays an increased incidence of cleft palate in humans (14).

CS occurs with an incidence of 12.5 per million births and results from genetic gain-of-function mutations in Fgfr2 (1). Craniofacial anomalies are its hallmark feature, including craniosynostosis, midface hypoplasia, proptosis, and oral anomalies such as an increased incidence of cleft palate, class III malocclusion, and a constricted dental arch. A narrow, high-arched palate is most commonly seen. Over 30 different FGFR2 mutations may result in CS, most of which localize to the FGFR2c isoform (16, 17), and therefore are mesenchymally expressed. All patients with CS are heterozygous for the mutation; homozygous mutations are presumed to be lethal.

A murine model of CS has been constructed using the most commonly observed mutation in human patients: a missense mutation of cysteine 342 (TGC→TAC) in exon 9 of the Fgfr2 gene (Fgfr2 C342Y) (18). This missense mutation results in unpaired cysteine residues, which cause FGFR2 dimerization via formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds, resulting in ligand-independent activation. The spectrum of palatal phenotypes in the mouse model closely parallels that of human patients with CS (19). In addition, the murine model allows evaluation of homozygous (Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y) embryos, which have a high incidence of cleft palate, and thus provides an excellent model for the investigation of palate development.

Murine palatogenesis closely resembles that of humans, consisting of well-delineated stages of palatal shelf outgrowth, elevation, and fusion between embryonic days (E) 13.5–15.5. Abnormalities in any of these events may result in cleft palate. In this study, we show that the C342Y substitution in Fgfr2 results in altered signaling, abnormal cellular proliferation, and altered production of the components of the extracellular matrix. We propose that these defects reduce palatal shelf elongation and delay palatal shelf elevation, the combination of which results in cleft palate.

Results

Fgfr2 Is Expressed in the Posterior Palate of Wild-Type Mice.

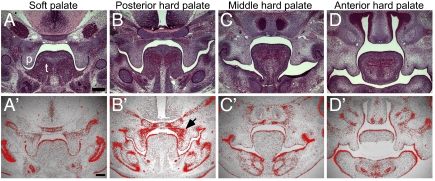

During mammalian development, palatal shelves extend along the lateral walls of the developing oropharynx and initially grow vertically on either side of the tongue. In the mouse (and rat), palatal shelves elevate at approximately E14.5 (20, 21). To determine where altered activity of the C342Y Fgfr2 mutation may regulate palate development, we examined Fgfr2 expression before shelf elevation. At E13.5 (Fig. S1) and pre-elevation E14.5 (Fig. 1), Fgfr2 expression was strongest in the posterior palatal shelf mesenchyme with strong focal expression on the superior nasal half of the shelf (Fig. 1B ′). Little expression was observed in the anterior, middle, and soft palate regions (Fig. 1 D′, C′, and A′, respectively). We therefore focused on the posterior palate in comparisons of CS and WT mice.

Fig. 1.

Fgfr2 expression in the wild-type murine palate. (A–D) H&E stained coronal sections through the soft palate, posterior, middle and anterior regions of the pre-elevation E14.5 WT mouse palate. (A′–D′) Fgfr2 in situ hybridization (red) on adjacent sections. The greatest Fgfr2 expression is seen in the superomedial portion of the posterior palate (arrow). p, palate; t, tongue. (Scale bar: 200 μM.)

Palatal Shelf Morphogenesis Is Altered in CS Embryos.

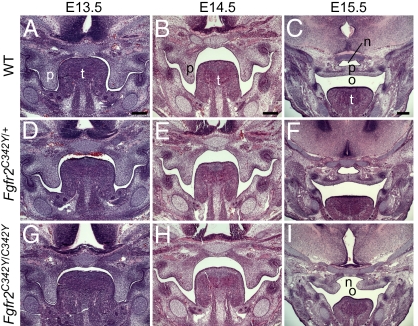

Normal palate development consists of three well-delineated stages: vertical palatal shelf outgrowth from the maxillary prominences beginning at E12.5 and continuing through E13.5; palatal shelf elevation, or reorientation, to a horizontal position above the tongue at E14.5; and dissolution of the medial epithelial seam and fusion of the palatal shelves by E15.5. Fgfr2C342Y/+ and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mice exhibited increased incidence of cleft palate. A total of 115 of 117 (98%) Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos displayed a cleft at the completion of palate development, whereas 9 of 234 (˜4%) Fgfr2C342Y/+ embryos examined displayed a palatal cleft. Qualitatively, Fgfr2C342Y/+ embryos displayed a larger spectrum of abnormalities in severity and timing compared with WT.

At E13.5, the palate shelves of both Fgfr2C342Y/+ and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos were similar to those of littermate controls (Fig. 2). E14.5 embryos, even from the same litter, displayed a variety of shelf morphologies that ranged from vertically oriented (Fig. 2B) to bilaterally elevated shelves. All E14.5 Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos examined, however, displayed vertically oriented shelves (23 of 23). In contrast, 30 of 61 Fgfr2C342Y/+ embryos displayed vertically oriented shelves at E14.5, whereas only 3 of 14 WT embryos had vertically oriented shelves at this developmental stage. When compared with the vertically oriented shelves of Fgfr2C342Y/+ and WT embryos at E14.5, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y shelves were relatively small, with an 11% (P < 0.03) reduction in height. At E15.5, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y shelves were elevated and contained a large gap that eventually manifests as the cleft palate phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Palate development in WT, Fgfr2C342Y/+, and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mice. (A, D, and G) E13.5, (B, E, and H) E14.5, and (C, F, and I) E15.5 H&E stained coronal sections of developing mouse palates. Normal palate development consists of palate shelf outgrowth (A), elevation (B), and fusion (C), whereas development of the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palate (G–I) is notable for narrower shelves, delayed elevation, and a cleft palate. Fgfr2C342Y/+ palate development (D–F) includes a spectrum of phenotypes, such as delayed elevation and normal fusion, shown here. n, nasal cavity; o, oral cavity; p, palate; t, tongue. (Scale bar: 200 μM.)

Palatal Shelf Outgrowth: Altered Proliferation, but Not Cell Death, in the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y and Fgfr2C342Y/+ Palate.

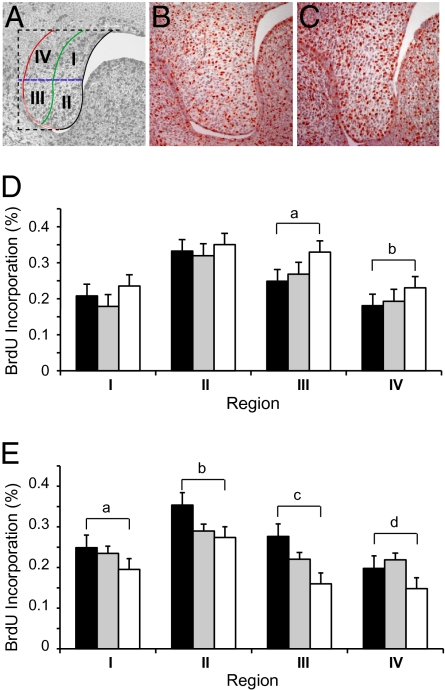

To assess both the growth of the palatal shelf and how differential growth could regulate morphogenesis, we divided the palatal shelf into four regions (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. 3A). Proliferation was quantified by counting BrdU-stained and total nuclei in each region. Compared with WT, the posterior palatal shelves from Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mice demonstrated significantly increased mesenchymal cellular proliferation at E13.5 in the oral half of the shelf (regions III and IV; Fig. 3 B–D). By E14.5, however, proliferation was significantly decreased throughout shelf mesenchyme (Fig. 3E). There were no differences in mesenchymal proliferation rates among genotypes at E15.5.

Fig. 3.

Cellular proliferation in developing WT, Fgfr2C342Y/+, and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates. (A) Palatal shelf division into four regions to quantify BrdU staining. (B–D) At E13.5, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates (C) have increased proliferation in regions III and IV compared with WT (B) palates (D; a, P < 0.004; b, P < 0.02, respectively; n = 4 or more for all genotypes). (E) At E14.5, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y show decreased BrdU incorporation compared to WT palates throughout the palate mesenchyme (a, P < 0.02 region I; b, P < 0.002 region II; c, P < 0.0007 region III; d, P < 0.02 region IV; n = 4 for all genotypes). Black bars, WT; gray bars, Fgfr2C342Y/+; white bars, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y.

To determine whether rates of cell death were affected by the CS mutation, TUNEL assays were carried out on E13.5 and E14.5 tissues. Low levels of apoptosis were noted in the mesenchyme and epithelium of all three genotypes at both time points. No differences in rates of cell death were noted among genotypes at E13.5 or E14.5 (Fig. S2).

Delayed Palatal Shelf Elevation: Altered GAG Levels in the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y and Fgfr2C342Y/+ Palate.

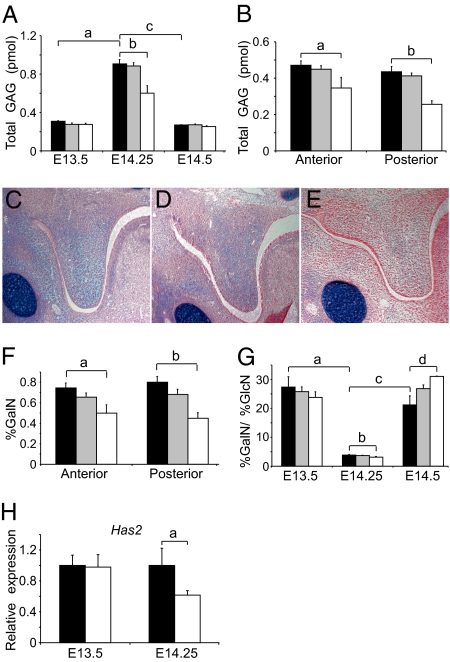

We assessed differences in GAG content within the palate, because GAG accumulation and hydration have been hypothesized to regulate elevation. Palate GAG quantification by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (22) showed an increase in total GAG content, standardized to glycine, in the whole palate of all genotypes just before shelf elevation compared with pre- and postelevation time points (Fig. 4A). Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos displayed decreased (P < 0.02) total GAG in the whole palate at E14.25 (Fig. 4A), and this finding was consistent within both the anterior (P < 0.05) and posterior (P < 0.02) palate before elevation (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the regional GAG HPLC analysis, Alcian blue staining, used to qualitatively assess total GAG levels in histologic sections, showed decreased staining in posterior palatal mesenchyme of Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos compared with WT and Fgfr2C342Y/+ littermates just before shelf elevation (early E14.5; Fig. 4 C–E).

Fig. 4.

Glycosaminoglycan accumulation, composition, and synthesis in developing WT, Fgfr2C342Y/+, and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates. (A) GAG accumulation during palate development (a, P < 0.001; b, P < 0.02; c, P < 0.001). (B) Compared with WT, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates have less total GAG accumulation in the anterior (a, P < 0.05) and posterior (b, P < 0.02) regions at E14.25. (C–E) WT (C) and Fgfr2C342Y/+ (D) palates show increased Alcian blue staining compared with Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y (E) in the posterior region at E14.5 (representative of three embryos for each genotype). (F) Decreased GalN composition is seen in both regions of the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palate at E14.25 compared with WT (a, P < 0.04; b, P < 0.02). (G) GalN/GlcN ratio in whole palatal shelves. All genotypes have a decreased ratio of GalN/GlcN in the whole palate just before elevation (E14.25; a, P < 0.001), and the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y GalN/GlcN ratio is further decreased compared with WT at E14.25 (b, P < 0.01). At E14.5, all genotypes show an increased GalN/GlcN ratio (c, P < 0.001), and the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y GalN/GlcN ratio is further increased compared with WT (d, P < 0.02). (H) Has2 expression was decreased in the posterior region of the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palate compared with WT at E14.25 (a, P < 0.05). Black bars, WT; gray bars, Fgfr2C342Y/+; white bars, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y.

In addition to decreased GAG quantities, HPLC data also showed altered GAG composition in the CS palates. Compared with WT, palates from Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos contained significantly (P < 0.05) decreased amounts of galactosamine (GalN) in both the anterior and posterior regions of the palate at E14.25 (Fig. 4F). Examination of the entire palatal shelf at E14.5 showed an increased ratio of galactosamine to glucosamine (GlcN) in the CS palates compared with WT (P < 0.03; Fig. 4G). A statistically significant (P < 0.01 for all genotypes) decrease in the ratio of galactosamine to glucosamine was apparent at E14.25 compared with E13.5, and to E14.5 for all genotypes as well (Fig. 4G). There were no differences in GAG quantity or content among genotypes earlier in development (E13.5) using either Alcian blue staining or HPLC; all differences in GAGs occurred near the time of palatal shelf elevation.

To test if hyaluronic acid (HA) biosynthetic enzyme expression is altered, quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess hyaluronic acid synthase 2 (Has2) expression. At E13.5, there were no differences in Has2 expression between Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos and WT (Fig. 4H). However, at E14.25, just before normal palate elevation, Has2 expression was significantly (P < 0.05) down-regulated in the posterior palate of Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos (Fig. 4H).

Palatal Shelf Fusion: Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y and Fgfr2C342Y/+ Palates Fuse.

To assess whether the CS palate was capable of fusion, dissected palatal shelves placed in direct contact with one another were grown in culture for 96 h. All palates (5/5) from each of the three genotypes (WT, Fgfr2C342Y/+, and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y) were capable of fusion in vitro in two separate experiments (Fig. S3).

Manipulation of FGF Signaling Affects in Vitro WT Palatal Shelf Development.

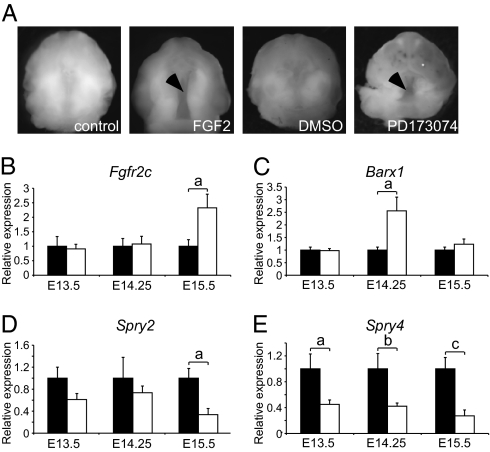

To better understand the FGF-FGFR signaling trend responsible for altered palate development in CS, we assessed the effects of FGF gain-of-function and loss-of-function signaling on normal palate development in vitro (Fig. 5A). E12.5 whole maxilla, including the early palatal shelves, were grown in organotypic culture for 72 h in the presence of FGF2, FGF18, or the FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor PD173074. Untreated and control WT palates showed normal elevation and fusion in vitro (24 of 24). Augmentation of FGF-FGFR signaling with FGF2 (1 μg/mL) resulted in cleft palate in 9 of 10 WT samples performed in four different experiments. Similarly, FGF18 (1 μg/mL) supplementation resulted in clefts in 6 of 6 WT palates over three different experiments. Interestingly, inhibition of the FGF-FGFR signaling pathway with PD173074 in WT palates also resulted in a 100% incidence (12 of 12) of clefting (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

FGF signaling and palate development: In vitro FGF signaling manipulation in WT palate and qPCR studies in WT and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y posterior palates. (A) WT palate explant cultures treated with FGF2 (1 μg/mL) or PD173074 (2 μM) exhibited cleft palate (arrows) compared with the fused palates of untreated and DMSO-treated control palates. (B) Compared with WT, the posterior palates of Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mice exhibit a 2-fold increase in relative expression of Fgfr2c at E15.5 (a, P < 0.02; n = 4 or more), but no differences at earlier time points. (C) Barx1 expression in the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y posterior palate increases greater than 2.5-fold (a, P < 0.05) at E14.25 (n = 7 or more). (D) Expression of Spry2 is decreased in Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mouse compared with WT at E15.5 (a, P < 0.04, n = 4 or more). (E) Expression of Spry4 is decreased throughout palate development (a, P < 0.01; b, P < 0.01; c, P < 0.03; n = 4 or more). Black bars, WT; white bars, Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y.

Altered FGFR Expression and Signaling in the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y Palate.

FGFR signaling within the posterior palatal shelves was investigated in WT and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos early in palatogenesis (E13.5), just before shelf elevation (E14.25) and after elevation (E15.5). Expression of the Fgfr2c isoform showed a significant (P < 0.02) 2-fold increase in the Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates at E15.5 but no differences in expression at earlier time points (Fig. 5B). No differences in expression of the FGF ligands Fgf9, Fgf10, or Fgf18; the FGF pathway antagonist Dusp6; or the FGFR/MAPK adaptor Frs2 were noted throughout palate development. Examination of FGF-responsive transcription factors Pea3 and Erm showed a trend (P = 0.06) toward increased Pea3 expression in Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palate at E13.5 and no differences in Erm expression throughout palate development. Barx1 is an FGF-regulated homeobox transcription factor expressed in craniofacial structures, including palate mesenchyme (23). Just before the time of palatal shelf elevation, Barx1 expression was significantly increased by greater than 2.5-fold (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C) in Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y palates. Sprouty (Spry) 2 and 4 are negative regulators of FGF signaling. Spry2, which is expressed in palate epithelium, showed a trend toward decreased expression throughout palate development (significant at E15.5; P < 0.04; Fig. 5D) and Spry4, which is expressed in palate mesenchyme, showed significantly decreased expression at all three time points (P < 0.01 for E13.5 and E14.25, P < 0.03 for E15.5; Fig. 5E).

Discussion

Defects in any of the stages that define normal palatogenesis may result in cleft palate. Examination of each of these developmental stages in CS mice showed abnormalities in palatal shelf outgrowth and elevation, but no defects in fusion. Examination of Fgfr2 expression localized the highest levels of expression to the posterior portions of the WT palatal shelf. Because the C342Y mutation in Fgfr2 is localized in the mesenchymal “c” splice form of Fgfr2, we focused our analysis on the posterior palate mesenchyme. Cellular proliferation in the posterior palate was initially increased in the oral half of the palatal shelf in the CS mice in a genetic dose-dependent fashion, whereas proliferation was decreased in the CS palate throughout the mesenchyme at E14.5. As signaling through FGFR2 is integral to cellular proliferation (24), these data suggest temporal alterations in levels of Fgfr2 signaling. Despite the genetic gain-of-function Fgfr2 mutation, the resulting effects on proliferation are not directly coupled to receptor activation. Multiple downstream mediators of FGF signaling may be activated or inhibited and may feedback to modulate overall activity. Importantly, proliferation is diminished in the CS palate just before shelf elevation. The overall consequence of expression of the mutant Fgfr2 is decreased growth, which results in palatal shelves that are both narrower and incapable of contacting one another after shelf elevation is complete, resulting in a palatal cleft.

Increased total GAG quantities were noted in the whole palates of all three genotypes just before the timing of normal palatal shelf elevation. This finding supports the concept that GAGs are integral to the elevation process. The initial hypothesis that hydration of GAGs produces expansion of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and therefore provides an intrinsic force within the palatal shelf tissue that allows palatal shelf elevation to occur, was postulated by Lazzaro in 1940 (25) and others (26 –35). During palatogenesis, hyaluronic acid and sulfated GAGs are present (26, 33). HA is one GAG component and makes up 60–65% of the ECM in the murine palate around the time of palatal shelf reorientation (26, 31). Levels of HA are elevated before shelf reorientation, and then decrease once elevation is complete (34, 35). Our data showing increased GAGs before shelf reorientation support those of Pratt et al. (26), who demonstrated HA synthesis in the 24 h before shelf closure. Experimental models have also shown suppressed GAG synthesis in teratogen-induced cleft palate (35, 36). Our data and previous models together support the necessity of GAG accumulation before palatal shelf reorientation.

The Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y mouse displayed a 24-h delay in palatal shelf elevation. Interestingly, administration of chlorcyclizine, a substance that enhances HA and chondroitin sulfate degradation without affecting GAG synthesis (27), to pregnant WT mice resulted in a 100% incidence of cleft palate in the offspring. The palates of these treated embryos demonstrated a 24-h delay in shelf size and shape in the palate (29). Similarly, delayed palatal shelf reorientation and decreased GAG synthesis were noted in the hamster after cleft palate induction with cyclophosphamide (36). The delay in palatal shelf elevation seen in the CS mouse is consistent with other experimental models that have shown decreased GAG accumulation.

Fgfr2 is localized to the posterior palate in regions shown to contain the greatest amounts of HA, a component integral to shelf elevation (28). Consistent with a role for mutant FGFR2 affecting palate development through regulation of GAG content, decreased GAG quantities were noted in the posterior CS palates compared with WT. FGF2 has been shown to modulate expression of GAGs and proteoglycans. In vitro treatment of human periodontal ligament cells with FGF2 resulted in increased heparin sulfate in the supernatant, and may also stimulate HAS1 and HAS2 (37). Has2 is one of three genes encoding HA synthesis and is present during palatogenesis (38). Decreased Has2 expression in the posterior CS palate may have a role in decreased HA accumulation and, interestingly, may also have a role in cellular proliferation as intracellular HA has been suggested as a regulator of proliferation (39). Taken together, decreased Has2 expression and decreased GAG quantities may result in a deficiency of GAG accumulation, which may result in reduced hydrostatic forces necessary for palatal shelf reorientation, resulting in delayed or even absent shelf elevation.

GAGs are divided into galactosamine (GalN)-containing GAGs and glucosamine (GlcN)-containing GAGs. GalN-containing GAGs include chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans interact with HA in assembling the ECM. GlcN-containing GAGs, on the other hand, include heparan sulfate, heparin, keratan sulfate, and HA. All genotypes displayed a significant decrease in the ratio of percentage GalN to GlcN content just before shelf elevation compared with pre-elevation and post-elevation time points, which may indicate decreased GalN-containing GAG biosynthesis/degradation and increased GlcN-containing GAG biosynthesis before shelf elevation. CS mice displayed significantly decreased percentages of GalN compared with WT in the posterior palate at E14.25, consistent with less overall GAG content. Examination of the palates at a slightly later time point showed increased amounts of galactosamine in the whole palate at the time of normal palate shelf elevation. This same pattern of increased galactosamine was noted by Bosi et al. (40) in fibroblasts from human patients with nonsyndromic cleft palate. This group also noted that treatment of normal fibroblasts with a teratogen that induces cleft palate, diphenylhydantoin, resulted in reduced GAG synthesis. In addition, similar patterns of decreased GAG and increased GalN were noted in calvarial fibroblasts in human patients with CS (41, 42). Our data fit not only with those of similar disease phenotypes, but also suggest possible similarities in the etiopathology of CS in different organ systems. In the palate, these abnormalities in GAG quantity and composition likely contribute to the delay in palatal elevation noted in the CS mouse, which is one of the key components of the cleft palate phenotype. The delay in shelf reorientation causes a loss of a critical developmental window in which shelf elevation allows for shelf fusion to occur normally.

The CS mouse displays abnormal cellular proliferation and ECM quantities and composition in the palate. These abnormalities affect two developmental stages, palatal shelf outgrowth and elevation, which may combine for a synergistic effect of altered palatal shelf volume. Adequate palatal shelf volume has been hypothesized as a mandatory prerequisite to enable shelf reorientation, or elevation, to occur. Shelf volume may be gained via three mechanisms: cellular proliferation (43, 44), cellular hypertrophy, or ECM accumulation and hydration (32, 34). In the CS mouse, decreased cellular proliferation and decreased ECM accumulation near the time of elevation may contribute to the delayed shelf reorientation phenomenon. The timing of these abnormalities provides a mechanistic clue; both abnormalities occur at or near the timing of palatal shelf elevation (there were no alterations in GAGs noted at earlier or later time points). The delay in shelf elevation is likely the key component of the cleft palate phenotype displayed in this model.

Although palatal shelf outgrowth and elevation are disrupted in the CS mouse model, the final phase of palatogenesis, palatal fusion, when isolated, remains intact. Palatal fusion involves the contact and then dissolution of the medial edge epithelium (MEE) of the opposing palatal shelves. This process is mediated by transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling (reviewed in ref. 45). Our data support the concept that the CS Fgfr2 mutation does not affect the TGFβ-mediated fusion process.

One of the most interesting and confounding findings of this work is that both augmentation and inhibition of FGF-FGFR signaling in vitro resulted in an identical phenotype, a cleft palate. These findings, perhaps more than any other data, support our hypothesis that the gain-of-function genetic mutation in CS may indeed result in a loss-of-function phenotype. Interestingly, in vivo evidence for this observation exists as well. Mice with a deletion encompassing Sprouty2 (Spry2), an antagonist of FGF signaling, exhibit cleft palate (46). In addition, conditional knockout of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 in palate mesenchyme results in cleft palate with 100% penetrance (Fig. S4). Clearly, the mechanistic explanation for this syndrome is not simple.

To better understand the signaling mechanisms responsible for the cleft palate phenotype in CS, qRT-PCR studies were completed on several genes of interest. FGF ligand (Fgf9, Fgf10, and Fgf18) and Fgfr2 expression showed no differences between the CS and WT genotypes throughout palate development, suggesting that feedback mechanisms resulting from constitutive activation of FGFR2 do not affect expression of FGF ligands known to function in palate development or FGFR2 itself. It is possible that the gain-of-function mutation in FGFR2 results in an initial increase in FGF-FGFR2 signaling that eventually reaches a threshold, and then becomes down-regulated. This could occur through complex interactions of downstream signaling cascades and feedback loops. Barx1 expression was increased in the posterior palates of the homozygous CS mice compared with WT at the time just before palatal shelf elevation, and both Spry2 and Spry4 expression were decreased during the time of palate development. These findings fit with the hypothesis of dynamic FGFR2 signaling levels. As FGF signaling regulates Spry gene expression, decreased Spry expression levels would indicate decreased FGFR2 signaling. Our findings of increased Barx1 expression in association with decreased Spry2 fit with those of Welsh et al. (46) in their construction of a mouse with a deletion encompassing Spry2. These mice exhibited cleft palate, and, in the absence of Spry2, the palatal mesenchyme displayed expanded and ectopic Barx1 expression. It is important to note, however, that decreased Spry2 expression resulting from an Fgfr2 mutation suggests a pathway in which Spry is downstream of FGFR signaling, whereas a genetic deletion of Spry2 itself is obviously a separate inciting event and may not be directly linked to FGFR signaling. The correlation of these studies, however, provides information about related signaling pathways and the idea that altered FGFR signaling results in cleft palate.

These studies suggest that a genetic gain-of-function Fgfr2 mutation may result in a loss-of-function phenotype; however, the underlying mechanism may be complex. The gain-of-function mutation does not simply translate to a gain-of-function phenotype; negative regulation of FGFR signaling can occur following hyperactivation of FGFR2 during palate development. We conclude that abnormal signaling resulting from the C342Y mutation in Fgfr2 is a critical regulator of cellular growth and production of components of the extracellular matrix (GAG quantities and composition) during palate development. These defects foster abnormal palatal shelf outgrowth and elevation, resulting in cleft palate, and it is these developmental processes that should be targeted for future prevention strategies and pharmacologic interventions.

Materials and Methods

Fgfr2C342Y/+ mice were maintained on a CD1 genetic background and intercrossed to generate litters with wild-type (WT), Fgfr2C342Y/+, and Fgfr2C342Y/C342Y embryos. Analysis of cell proliferation, cell death, GAG content, qRT-PCR, and palate cultures are described in detail in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Smith and G. Schmid for technical assistance, and G. Morriss-Kay and C. Babbs for advice. We thank Dr. S. Mackinnon for providing C.A.P. and A.S.W. the opportunity for research. This work was supported by the Plastic Surgery Educational Foundation (A.S.W.), National Institutes of Health Grant HD049808, and the Virginia Friedhofer Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0913985107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wilkie AO. Bad bones, absent smell, selfish testes: The pleiotropic consequences of human FGF receptor mutations. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajihosseini MK. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in cranial suture development and pathogenesis. Front Oral Biol. 2008;12:160–177. doi: 10.1159/000115037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marie PJ, Coffin JD, Hurley MM. FGF and FGFR signaling in chondrodysplasias and craniosynostosis. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:888–896. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. FGF signaling pathways in endochondral and intramembranous bone development and human genetic disease. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1446–1465. doi: 10.1101/gad.990702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDowell LM, et al. Inhibition or activation of Apert syndrome FGFR2 (S252W) signaling by specific glycosaminoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6924–6930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley BM, et al. Impaired FGF signaling contributes to cleft lip and palate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4512–4517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607956104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice R, et al. Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1692–1700. doi: 10.1172/JCI20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alappat SR, et al. The cellular and molecular etiology of the cleft secondary palate in Fgf10 mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2005;277:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Xu J, Colvin JS, Ornitz DM. Coordination of chondrogenesis and osteogenesis by fibroblast growth factor 18. Genes Dev. 2002;16:859–869. doi: 10.1101/gad.965602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slaney SF, et al. Differential effects of FGFR2 mutations on syndactyly and cleft palate in Apert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:923–932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodé C, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:463–465. doi: 10.1038/ng1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mølsted K, Kjaer I, Giwercman A, Vesterhauge S, Skakkebaek NE. Craniofacial morphology in patients with Kallmann’s syndrome with and without cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34:417–424. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0417_cmipwk_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson SJ, Pruzansky S. Palatal anomalies in the syndromes of Apert and Crouzon. Cleft Palate J. 1974;11:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tompach PC, Zeitler DL. Kallmann syndrome with associated cleft lip and palate: Case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:85–87. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kan SH, et al. Genomic screening of fibroblast growth-factor receptor 2 reveals a wide spectrum of mutations in patients with syndromic craniosynostosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:472–486. doi: 10.1086/338758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen MMJ. FGFs/FGFRs and associated disorders. In: Epstein CJ, Erickson RP, Wynshaw-Boris A, editors. Inborn Errors of Development: The Molecular Basis of Clinical Disorders on Morphogenesis. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2004. pp. 380–400. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eswarakumar VP, Horowitz MC, Locklin R, Morriss-Kay GM, Lonai P. A gain-of-function mutation of Fgfr2c demonstrates the roles of this receptor variant in osteogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12555–12560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405031101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perlyn CA, et al. The craniofacial phenotype of the Crouzon mouse: Analysis of a model for syndromic craniosynostosis using three-dimensional MicroCT. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:740–748. doi: 10.1597/05-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferguson MW. Palate development. Development. 1988;103(Suppl):41–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson MW. Palatal shelf elevation in the Wistar rat fetus. J Anat. 1978;125:555–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studelska DR, Giljum K, McDowell LM, Zhang L. Quantification of glycosaminoglycans by reversed-phase HPLC separation of fluorescent isoindole derivatives. Glycobiology. 2006;16:65–72. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tissier-Seta JP, et al. Barx1, a new mouse homeodomain transcription factor expressed in cranio-facial ectomesenchyme and the stomach. Mech Dev. 1995;51:3–15. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00343-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iseki S, Wilkie AO, Morriss-Kay GM. Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 have distinct differentiation- and proliferation-related roles in the developing mouse skull vault. Development. 1999;126:5611–5620. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazzaro C. The mechanism of closure of the secondary palate (Translated from Italian) Monitore zoologico italiano. 1940;51:249–273. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratt RM, Goggins JF, Wilk AL, King CT. Acid mucopolysaccharide synthesis in the secondary palate of the developing rat at the time of rotation and fusion. Dev Biol. 1973;32:230–237. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilk AL, King CT, Pratt RM. Chlorcyclizine induction of cleft palate in the rat: Degradation of palatal glycosaminoglycans. Teratology. 1978;18:199–209. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420180205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkley LL, Morris-Wiman J. Computer-assisted analysis of hyaluronate distribution during morphogenesis of the mouse secondary palate. Development. 1987;100:629–635. doi: 10.1242/dev.100.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinkley LL, Morris-Wiman J. Effects of chlorcyclizine-induced glycosaminoglycan alterations on patterns of hyaluronate distribution during morphogenesis of the mouse secondary palate. Development. 1987;100:637–640. doi: 10.1242/dev.100.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brinkley LL, Vickerman MM. The effects of chlorcyclizine-induced alterations of glycosaminoglycans on mouse palatal shelf elevation in vivo and in vitro. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;69:193–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudsen TB, Bulleit RF, Zimmerman EF. Histochemical localization of glycosaminoglycans during morphogenesis of the secondary palate in mice. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1985;173:137–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00707312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris-Wiman J, Brinkley L. An extracellular matrix infrastructure provides support for murine secondary palatal shelf remodelling. Anat Rec. 1992;234:575–586. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092340413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young AV, Hehn BM, Cheng KM, Shah RM. A comparative study on the effects of 5-fluorouracil on glycosaminoglycan synthesis during palate development in quail and hamster. Histol Histopathol. 1994;9:515–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh GD, Moxham BJ, Langley MS, Waddington RJ, Embery G. Changes in the composition of glycosaminoglycans during normal palatogenesis in the rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1994;39:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh GD, Moxham BJ, Langley MS, Embery G. Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis during 5-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine-induced palatal clefts in the rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:355–363. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah RM, Izadnegahdar MF, Hehn BM, Young AV. In vivo/in vitro studies on the effects of cyclophosphamide on growth and differentiation of hamster palate. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:204–212. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimabukuro Y, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor regulates expression of heparan sulfate in human periodontal ligament cells. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tien JY, Spicer AP. Three vertebrate hyaluronan synthases are expressed during mouse development in distinct spatial and temporal patterns. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:130–141. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evanko SP, Wight TN. Intracellular localization of hyaluronan in proliferating cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1331–1342. doi: 10.1177/002215549904701013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosi G, et al. Diphenylhydantoin affects glycosaminoglycans and collagen production by human fibroblasts from cleft palate patients. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1613–1621. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770080901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodo M, et al. Effects of interleukins on Crouzon fibroblast phenotype in vitro. Release of cytokines and IL-6 mRNA expression. Cytokine. 1996;8:772–783. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baroni T, et al. Crouzon’s syndrome: Differential in vitro secretion of bFGF, TGFbeta I isoforms and extracellular matrix macromolecules in patients with FGFR2 gene mutation. Cytokine. 2002;19:94–101. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah RM, Arcadi F, Suen R, Burdett DN. Effects of cyclophosphamide on the secondary palate development in golden Syrian hamster: Teratology, morphology, and morphometry. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1989;9:381–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh GD, Moxham BJ. Cellular activity in the developing palate of the rat assessed by the staining of nucleolar organiser regions. J Anat. 1993;182:163–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng L, Bian Z, Torensma R, Von den Hoff JW. Biological mechanisms in palatogenesis and cleft palate. J Dent Res. 2009;88:22–33. doi: 10.1177/0022034508327868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welsh IC, Hagge-Greenberg A, O’Brien TP. A dosage-dependent role for Spry2 in growth and patterning during palate development. Mech Dev. 2007;124:746–761. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.