Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene amplification is the most common genetic alteration in high-grade glioma, and ≈50% of EGFR-amplified tumors also harbor a constitutively active mutant form of the receptor, ΔEGFR. Although ΔEGFR greatly enhances tumor growth and is thus an attractive target for anti-glioma therapies, recent clinical experiences with EGFR kinase inhibitors have been disappointing, because resistance is common and tumors eventually recur. Interestingly, it has not been established whether ΔEGFR is required for maintenance of glioma growth in vivo, and, by extension, if it truly represents a rational therapeutic target. Here, we demonstrate that in vivo silencing of regulatable ΔEGFR with doxycycline attenuates glioma growth and, therefore, that it is crucial for maintenance of enhanced tumorigenicity. Similar to the clinical experience, tumors eventually regained aggressive growth after a period of stasis, but interestingly, without re-expression of ΔEGFR. To determine how tumors acquired this ability, we found that a unique gene, KLHDC8, herein referred to as SΔE (Substitute for ΔEGFR Expression)-1, is highly expressed in these tumors, which have escaped dependence on ΔEGFR. SΔE-1 is also expressed in human gliomas and knockdown of its expression in ΔEGFR-independent “escaper” tumors suppressed tumor growth. Taken together, we conclude that ΔEGFR is required for both glioma establishment and maintenance, and that gliomas undergo selective pressure in vivo to employ alternative compensatory pathways to maintain aggressiveness in the event of EGFR silencing. Such alternative pathways function as substitutes for ΔEGFR signaling and should therefore be considered as potential targets for additional therapy.

Keywords: tumorigenicity, gliomblastoma, epidermal growth factor receptor

Malignant gliomas are the most common type of primary brain tumors. Glioblastoma, the most malignant form of glioma, remains mostly incurable despite intensive treatment including surgical resection, irradiation, and chemotherapy (1). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene amplification occurs in ≈30–50% of all glioblastomas, and the amplified genes are frequently rearranged (2, 3). An in-frame deletion of exons 2–7 of EGFR (referred to here as ΔEGFR), is the most commonly occurring mutant form of the EGFR in these tumors (4), is constitutively activated, and confers enhanced tumorigenicity to glioblastoma cells in vivo by reducing apoptosis and increasing proliferation (5 –7). Patients with tumors expressing ΔEGFR have a poorer prognosis than those that do not (8, 9).

ΔEGFR has been used as a tumor-specific drug target in kinase inhibitor, antibody-based immunotherapy, immunotoxin, peptide vaccination, and small interfering RNA (siRNA) approaches (10). For such approaches to be ultimately successful, the target would ideally be required for the maintenance of tumor growth, not only for its initiation. This notion has been demonstrated for other oncogenes such as ras, and wild-type-EGFR in other tumor types (11 –14) but has not been shown for ΔEGFR in glioblastoma or any other tumor type. Moreover, although it has been shown that a glioblastoma subgroup coexpressing ΔEGFR and PTEN initially respond to EGFR targeted therapy (15), recent experience shows that even responsive tumors will eventually grow through the therapy (16, 17). Therefore, an understanding of the mechanisms that tumor cells use to overcome receptor inhibition is of substantial importance in designing useful therapies.

In some cases, resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy arises either due to desensitizing mutations in the kinase itself or through the activation of alternate oncogenic pathways (18). Recently, it has also been shown that other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as PDGFR, IGF1-R, and c-Met can be concurrently up-regulated in glioblastomas, resulting in compensation for decreased signaling by ΔEGFR (19 –21). All of these studies demonstrate that tumor cells are adept at overcoming single targeted therapies and suggest that understanding the various mechanisms used to this end could provide very useful information with which to design more effective therapies that are more difficult to overcome. Here, we sought to define such mechanisms by using glioma cells that conditionally express ΔEGFR in vivo to test the requirement of ΔEGFR for maintenance of enhanced tumor growth and to uncover alternate pathways that gliomas may employ to bypass ΔEGFR inhibition.

Results

Glioma Cells that Express ΔEGFR Regulated by Doxycycline.

To determine whether ongoing ΔEGFR expression was essential for tumor establishment and maintenance, we developed a tetracycline-regulatable expression system, in which the ΔEGFR level in tumor xenografts is repressed by administering doxycycline-containing drinking water to engrafted mice. We selected the human high-grade glioma cell line U373MG for these studies because it requires ΔEGFR expression for xenograft establishment in mice. As shown in Fig. S1A, U373MG cells constitutively expressing ΔEGFR formed tumors in nude mice, whereas neither control U373MG-Luc cells nor U373MG-wt.EGFR cells were able to do so. To construct tetracycline-regulatable expression in these cells, a U373MG clone that expresses the tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) was first produced and verified. Then, either pΔCMV/(tetO)-ΔEGFR-IRES2-EGFP or pΔCMV/(tetO)-ΔEGFR-DK-IRES2-EGFP vectors that express ΔEGFR or its kinase-deficient mutant, DK, together with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) from a single bicistronic mRNA, were engineered into this tet-regulatable U373MG clone (Fig. S1B). Cells that had higher GFP expression were collected by two rounds of fluorescence activated cell sorting to enrich for cells that highly expressed ΔEGFR. In these tet-regulatable ΔEGFR-expressing U373 cells, both ΔEGFR and GFP expression could be silenced within 2–4 days after exposure to the tetracycline analog, doxycycline (Dox) (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 C and D).

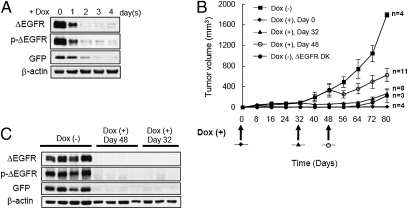

Fig. 1.

ΔEGFR-dependent tumor growth of U373MG cells expressing doxycycline-regulatable ΔEGFR. (A) Western blot analysis of proteins from whole-cell lysates with the indicated antibodies of engineered U373MG cells cultured in medium containing 1 μg/mL dox for 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days. (B) Tumor growth of U373MG cells (3 × 106) expressing dox-regulatable ΔEGFR injected s.c. into the flanks of nude mice that received dox-containing drinking water as indicated by arrows at 0, 32, or 48 days. One group of mice received U373MG cells expressing kinase-defective ΔEGFR (DK) and no doxycycline. Similar experiments were done at least twice with consistent results. (mean ± SEM) (C) Western blot analysis of lysates from mouse tumors in A that received no dox or received dox at day 32 or 48.

Growth of U373MG Cells Expressing Tetracycline-Regulated ΔEGFR in Vitro and in Vivo.

To determine whether tetracycline-regulated ΔEGFR imparted enhanced in vitro growth to U373MG cells, cell proliferation was analyzed by WST assays. Consistent with previous results (5), there were no significant differences in the in vitro growth rates between cells expressing ΔEGFR (-Dox) and cells silenced for ΔEGFR expression (+Dox), as well as no adverse effect of doxycycline on U373MG cells that constitutively express ΔEGFR (Fig. S1E).

To investigate the tumorigenicity of tetracycline-regulatable ΔEGFR-expressing U373MG cells in vivo, cells were engrafted s.c. into nude mice. Mice that were given doxycycline in their drinking water (+Dox) failed to develop tumors even after 80 days. However, when dox was omitted from the water (-Dox), ΔEGFR was expressed and this resulted in rapid tumor formation (Fig. 1B). When tumors were allowed to establish for 32 or 48 days, and then switched to +Dox conditions, resulting in the complete silencing of ΔEGFR expression (Fig. 1C), these tumors underwent an extended period of stasis (Fig. 1B). As a control, U373MG cells expressing tetracycline-regulated DK did not form tumors in nude mice. These results indicate the dependency of establishing U373 gliomas and of their continued enhanced growth in vivo on catalytically active mutant EGFR.

Decreased Proliferation in U373MG Tumors Silenced for ΔEGFR Expression.

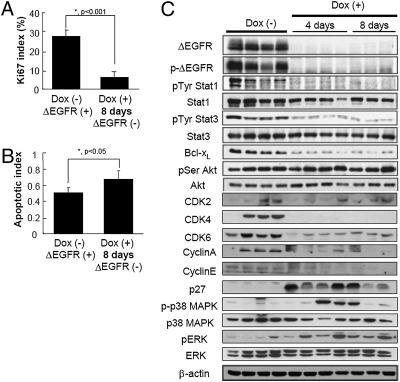

To investigate the effects of ΔEGFR silencing in the tumors, cell proliferation rates, apoptotic indices and signaling downstream of activated EGFR after administration of doxycycline were analyzed. Tetracycline-regulatable U373MG cells (3 × 106) expressing ΔEGFR were injected s.c. into the flanks of nude mice and ΔEGFR-driven tumors were allowed to establish. When tumor volumes reached an analyzable size (272 ± 138 mm3 at day 56), these mice were separated into two groups, and doxycycline-containing water was provided to one group only. Tumors continued to grow in mice that remained on normal drinking water (-dox), whereas tumors regressed in mice receiving doxycycline-containing water (+dox). Tumors were resected at 4 days after doxycycline administration when –dox tumors reached a size of 433 ± 237 mm3 and +dox tumors reached a size of 211 ± 86 mm3. Tumors were also harvested at 8 days after doxycycline administration in a separate experiment when –dox tumors reached a size of 357 ± 300 mm3 and +dox tumors reached a size of 141 ± 95 mm3. The growth rate of tumors during the first 4 days with and without suppression of ΔEGFR were statistically different (−20 ± 15% and +45 ± 22%, respectively; P < 0.001; Student’s t test), and a significant (P < 0.001; Student’s t test) reduction in proliferation (K i-67) was observed in ΔEGFR-negative tumors at 4 and 8 days (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2 A and B). These tumors also showed a slight increase (P = 0.064 at 4 days and P < 0.05 at 8 days; Student’s t test) in apoptosis (TUNEL staining) (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2C), whereas there was no significant difference (P > 0.1; Student’s t test) in microvessel area (CD31 staining) (Fig. S2D).

Fig. 2.

Growth characteristics and pathway profiling of U373MG tumors upon silencing of ΔEGFR expression. Mice bearing established s.c. U373MG dox-regulatable ΔEGFR tumors remained on normal drinking water [Dox (−)], or were administered dox-containing drinking water for 4 or 8 days [Dox (+)], and tumors were resected and analyzed. (A) Profileration index as measured by counting proportion of K i-67-positive cells (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.001, Student’s t test). ( B) Apoptotic index as measured by percentage of TUNEL-positive cells (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05, Student’s t test). (C) Western blot analysis of proteins from tumor lysates with the indicated antibodies. Each lane represents a tumor from an individual mouse.

In those tumors that no longer expressed ΔEGFR, diminished expression of the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-xL was observed as would be expected for reduced ΔEGFR signaling (Fig. 2C) (6). There was no difference in phosphorylation of serine residue of Akt, which is likely due to the strong possibility that growth factors present in the tumor microenvironment elicit signaling through the PI3-K pathway even in the absence of ΔEGFR. Also as expected for tumors that exhibit growth stasis, the expression of proteins involved in cell cycle progression and proliferation, such as CyclinA, CyclinE, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, and activation of Stat1/3 showed trends toward decreases in ΔEGFR-negative tumors compared to ΔEGFR-positive control tumors (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, p27, which acts in a negative fashion to prevent cell cycle progression, was expressed at very low levels in ΔEGFR-positive tumors and increased in ΔEGFR-negative tumors (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, we also observed a substantial increase in the phosphorylation of both ERK and p38 MAPK after silencing of ΔEGFR (Fig. 2C), suggesting that ΔEGFR signaling in vivo is mediated primarily by pathways other than MAPK. Furthermore, the tumor regression we observed indicates that the increase in MAPK phosphorylation is not immediately sufficient to support further tumor growth at these early timepoints. Overall, these results indicate that initial tumor regression after silencing of ΔEGFR expression is predominantly marked by a reduction in cell proliferation, which is governed by alterations in STAT1/3 transcriptional activity as well as apoptotic and cell cycle machinery.

Breakthrough U373MG Tumor Growth Independent of ΔEGFR.

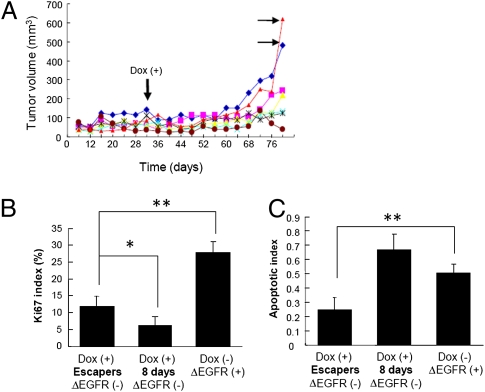

After an extended period of stasis, some tumors [11 of 19 total individual tumors (58%)] in which ΔEGFR expression had been repressed by exposure to dox eventually regained aggressive growth over the period of the experiment. When they did so, they then grew with kinetics similar to ΔEGFR-expressing tumors (indicated by the horizontal arrows in Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis demonstrated that these breakthrough tumors, hereafter referred to as “escapers,” did not result from the re-expression of ΔEGFR (Fig. 4), implying that this outgrowth might be prompted by compensatory pathways that confer similar enhanced tumorigenicity as does ΔEGFR. These breakthrough tumors showed an increase in cell proliferation (K i-67 staining) compared with the initial silencing of ΔEGFR, but proliferation in the escapers remained lower than that observed in the original ΔEGFR-dependent tumors (Fig. 3B). In contrast, apoptosis in the escapers as measured by TUNEL staining was substantially decreased compared to the ΔEGFR-dependent tumors (Fig. 3C). There was no significant difference in microvessel area by CD31 staining (P > 0.1, ANOVA; Fig. S3A). Together, these results suggest that resistance to apoptosis rather than an increase in proliferation may be a predominant mechanism for escape.

Fig. 3.

Relapse of U373MG tumors after silencing of ΔEGFR expression. (A) Tumor growth of U373MG cells (3 × 106) expressing dox-regulatable ΔEGFR injected s.c. into the flanks of nude mice administered dox-containing drinking water 32 days after injection. Each line represents an individual growth curve of a tumor in a mouse from one typical experiment. Horizontal arrows indicate representative cases of ΔEGFR-independent “escaper” tumors. (B) Proliferation index as measured by counting proportion of K i-67 positive cells in escaper and ΔEGFR-dependent (with Dox for 8 days from day 32 or without Dox) tumors (mean ± SD; P < 0.0001, ANOVA; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, Tukey–Kramer HSD test). (C) Apoptotic index in same tumors as part (B), as measured by TUNEL staining (mean ± SD; P < 0.0001, ANOVA; **, P < 0.01, Tukey–Kramer HSD test).

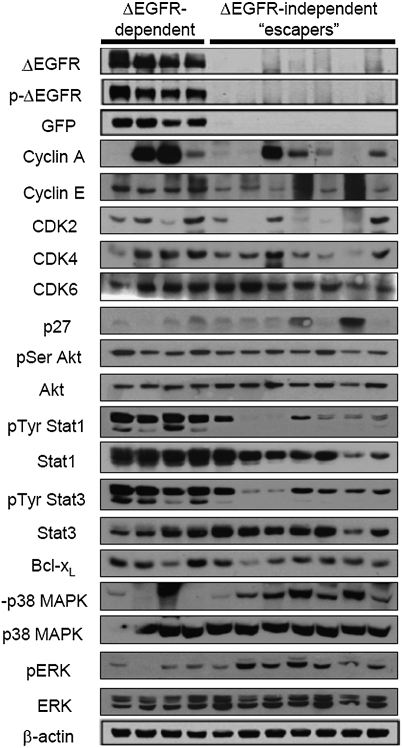

Fig. 4.

Analysis of ΔEGFR-dependent vs. escaper tumor protein expression and signaling pathway preferences. Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies of lysates derived from s.c. tumors from mice without dox in the drinking water (ΔEGFR-dependent) and escaper tumors that showed regrowth after a period of stasis after initial dox administration as in Fig. 3 (ΔEGFR-independent escapers). Analysis was performed at least three times for each antibody with consistent results.

Identification of Pathways that Compensate for Lack of ΔEGFR Expression and Promote Tumor Development.

To uncover the mechanisms underlying the acquisition of ΔEGFR-independent growth, we first investigated proteins and signaling pathways that were initially affected by ΔEGFR silencing to determine if compensation led to the emergence of escaper tumors. Western blot analysis revealed that some escaper tumors expressed the growth-promoting proteins CyclinA, CyclinE, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 at a similar level as ΔEGFR-dependent tumors (Fig. 4), which is in contrast to the very low levels of these proteins observed during the period of stasis after initial ΔEGFR silencing (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, most breakthrough tumors exhibited a low level of growth-inhibiting p27 protein (Fig. 4), again in contrast to the increased p27 observed immediately after ΔEGFR silencing (Fig. 2C). The majority of breakthrough tumors also exhibited slightly elevated Stat1/3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4) in comparison with the very low levels observed during the initial response (Fig. 2C). Bcl-xL was expressed at levels similar to ΔEGFR-positive tumors (Fig. 4), in striking contrast to the down-regulation of this antiapoptotic protein after ΔEGFR silencing (Fig. 2C). There was no alteration in the phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 4). Interestingly, compensation by cell cycle progression proteins and Stat transcription factors, although likely contributory in some tumors, was not a uniform or consistent observation among the escapers (Fig. 4). The increased phosphorylation of ERK and p38 MAPK that was observed initially after ΔEGFR silencing (Fig. 2C), however, was clearly maintained in all but one escaper tumor (Fig. 4). This finding suggests the possibility that suppression of these pathways by ΔEGFR, although not able to promote tumor growth or maintenance initially after ΔEGFR silencing, may impact later breakthrough tumor growth.

To confirm that the breakthrough tumors had acquired a stable ΔEGFR-independent tumorigenic phenotype, secondary cell lines were established from ΔEGFR-independent tumor xenografts, and their tumorigenic behaviors were compared to those of cells established from ΔEGFR-dependent xenografts. Established cell lines, whose ΔEGFR expressions were suppressed by doxycycline, were reinjected into nude mice. As shown in Fig. S3B, most of the cell lines established from breakthrough tumors showed substantial tumorigenic ability in the absence of ΔEGFR signaling (i.e., in the presence of doxycycline), whereas all three cell lines established from ΔEGFR-dependent tumors (size of tumors when resected for culture were 72, 56, and 64 mm3, respectively) could only develop small tumors in the presence of doxycycline at 84 days after inoculation (Fig. S3C). These same ΔEGFR-dependent cell lines were able to develop tumors rapidly in the absence of doxycycline when ΔEGFR was expressed (Fig. S3D). Even though there was an obvious difference in tumor growth in vivo in mice, no obvious differences in cell growth could be detected in vitro between original U373MG cells expressing tetracycline-regulatable ΔEGFR and representative ΔEGFR-independent U373MG cell lines (Fig. S3E). These results indicate that the breakthrough tumor phenotype of ΔEGFR-independent escaper tumors is stable upon cell line establishment and serial xenografting.

Interestingly, we did not detect any obvious reactivation of expected downstream pathways in established ΔEGFR-independent cell lines without serum stimulation (Fig. S3F). Using RTK arrays to search for other receptor tyrosine kinases that could potentially substitute for ΔEGFR (21), we observed modest increases in the expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) in these ΔEGFR-independent cell lines (Fig. S3F), which has been previously reported, to compensate for inhibited ΔEGFR signaling through PI3K-Akt activation (19). However, we also observed up-regulation of IGF1R in cell lines established from large s.c. tumors that depended on ΔEGFR expression for their growth, suggesting that IGF1R and ΔEGFR expression may not be mutually exclusive and that IGF-1R is unlikely to play the sort of compensatory role that develops when ΔEGFR expression is silenced.

To more closely examine candidates that may be responsible for this ΔEGFR-independent in vivo growth, we next used microarrays to compare gene expression profiles of ΔEGFR-independent escaper cell lines to those of control cell lines (DK and ΔEGFR cells grown in the presence and absence of dox and ΔEGFR-dependent tumor-derived cell lines). Informatic analysis of the data revealed 25 up-regulated and 10 down-regulated genes (34 and 14 probe sets, respectively) with expression patterns that suggested their potential for being responsible for ΔEGFR-independent growth (Fig. S4A and Tables S1 and S2) To determine whether the breakthrough tumors were the trivial consequence of selection of preexisting aberrant cells within the original populations, DNA from ΔEGFR-independent cells was analyzed by using high-resolution long oligonucleotide-based CGH arrays. Although this approach would allow the detection of copy number alterations, such as genomic amplifications or deletions, that may occur either in the original population or during resumption of tumor growth (22), genomic differences between cell lines were extremely rare (Fig. S4B), indicating that most of the changes in gene expression in U373 ΔEGFR-independent tumors likely resulted from epigenetic modifications or transcriptional alterations in cells of the same genotypes.

SΔE-1/KLHDC8A Is Expressed in Human Glioblastoma and in Tumors Growing Independent of ΔEGFR.

Among the list of the 35 candidate genes determined by RNA expression microarray analysis, we focused on a unique gene, Kelch domain containing 8A (KLHDC8A), because this gene showed the second highest fold increase (4.6-fold) in ΔEGFR-independent cell lines and public microarray databases indicated its striking overexpression in glioblastoma tissues compared to normal brain tissue (Figs. S4A and S5A). To verify the microarray data, we performed quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Fig. S5B) and Northern blot analysis (Fig. S5C) and found remarkably increased expression of KLHDC8A in cells established from tumors attaining growth independent of ΔEGFR. Because this gene was representative of several genes overexpressed in ΔEGFR-independent cell lines, we refer to it as Substitute for ΔEGFR Expression 1 (SΔE-1). It was highly expressed in xenografts that showed aggressive tumor growth in mice after they escaped from suppressed ΔEGFR expression, whereas only very low expression was detected in tumors of various sizes whose growth was supported by ΔEGFR expression (Fig. S5B). SΔE-1 expression was also significantly higher in human glioblastoma specimens than in normal brains (Fig. S5D). To further explore expression of this gene, we raised a rabbit anti-human SΔE-1/KLHDC8A polyclonal antibody, which also recognized the mouse Klhdc8a homolog (Fig. S5E). Using this antibody, we observed marked overexpression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A exclusively in tumors that were able to grow rapidly after escaping suppressed ΔEGFR expression (Fig. 5A), and in a series of human glioblastoma tissues (Fig. S5F), although proteins detected in both sets of samples were a few kilodaltons smaller in molecular mass than that of overexpressed full length SΔE-1 protein. This size difference suggests that additional modification or processing of predicted full-length protein may be necessary for this gene to become functional. Interestingly, the established escaper cell line with the least tumorigenic potential, Esc-3, showed the lowest SΔE-1 protein expression (Fig. 5A).

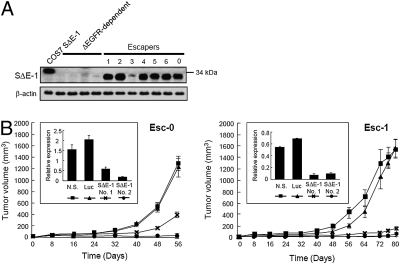

Fig. 5.

Increased expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A in ΔEGFR-independent U373MG cells and GBMs and effect of knock-down on tumorigenicity. (A) Western blot analysis of lysates from ΔEGFR-dependent or -independent escaper tumors as in Fig. 4 with a polyclonal rabbit anti-SΔE-1 antibody. Cos7 cells transfected with SΔE-1 were used as a positive control for the antibody. (B Inset) Two tet-regulatable U373MG cell lines established from escaper tumors, Esc-0 and Esc-1, were infected with shRNA-expressing retroviruses targeting SΔE-1/KLHDC8A (No. 1 or No. 2), a nonspecific sequence (N.S.), or Luciferase (Luc), and stable cell lines were established. qPCR analysis of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A gene expression was performed in the cell lines expressing the indicated retroviral shRNA constructs. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three replicates. y axis represents the relative gene expression level. These cells (3 × 106) were injected s.c. into the flanks of nude mice fed with dox-containing drinking water. Tumor volumes were measured at the indicated times to generate the growth curve of tumors with knockdown of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A expression. n = 8 mice for all groups, mean ± SEM.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis using the unique antibody demonstrated that SΔE-1/KLHDC8A protein was expressed in >85% of GBM patient tumors (n = 33) (Table S3). In most tumors, 10–40% of tumor cells expressed the protein and the intensity of staining in individual tumor cells was heterogeneous with low to moderate staining detected in most patient samples (Fig. S5G and Table S3), while low in normal brain (23, 24).

Suppression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A Expression Decreases Tumorigenicity of U373 ΔEGFR-Independent Cells.

To investigate the significance of increased expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A, shRNAs were used to knock down the expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A in two representative ΔEGFR-independent U373 cell lines (Fig. 5B Inset). This resulted in a significant suppression in tumor formation when compared to control cells producing a negative control shRNA (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results suggest that SΔE-1/KLHDC8A is required for the tumorigenic potential of derived ΔEGFR-independent U373 cells.

Discussion

Here, we tested the dependence of glioblastoma on ΔEGFR expression for growth. The results demonstrated that catalytically active ΔEGFR is required for tumor establishment and, upon silencing its expression, is required for the maintenance of the enhanced tumor growth conferred by the receptor. After a period of tumor regression or stasis, resumption of growth (“escape”) often occurred, reminiscent of clinical trails showing eventual resistance to receptor-targeted therapy with drugs such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors or antibodies. As potential mechanisms of ΔEGFR-independent growth, we initially suspected that ΔEGFR acquired unregulated expression or that compensatory pathways were activated that might phenocopy ΔEGFR activity (18, 25). However, neither unregulated ΔEGFR overexpression nor apparent reactivation of expected downstream signaling (either as compensation for ΔEGFR or through activation of other receptor tyrosine kinases) could be observed. These results suggested that other unsuspected pathways might have been activated that became critical in these ΔEGFR-independent cell lines. To uncover such pathways, we analyzed cell cycle, signal transduction, and apoptosis pathway associated proteins as well as assessed global gene expression changes by expression microarray analyses. In summary, these approaches illustrated that the majority of escaper tumors restore their tumorigenic growth chiefly through a switch in signaling pathways, from a ΔEGFR-driven signature of activated Stat1/3, low p38, and Erk activation to one of low Stat1/3 activity, high p38 and Erk activation, reminiscent of a signaling fingerprint associated with EGFR activation (20), despite the absence of this receptor. Additionally, down-regulation of Bcl-xL seen upon initial ΔEGFR silencing was restored when tumors resumed growth, in agreement with suppression of apoptosis as a major mechanism leading to emergence of the escaper phenotype.

Analysis of the escaper transcriptome identified a group of up-regulated genes among which was a unique gene, termed SΔE-1/KLHDC8A. This gene appears to be responsible for tumor relapse after ΔEGFR silencing in several of the breakthrough tumors. This conclusion was supported by demonstrating that shRNA-based knock-down of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A led to decreased tumorigenicity and implies an important link with pathways using this gene and ΔEGFR-targeted therapies. SΔE-1/KLHDC8A is a 350-amino acid protein that belongs to the kelch repeat superfamily and shares >95% amino acid sequence identity with the predicted mouse or rat klhdc8a homolog. Each kelch motif is a segment of 44–56 amino acids in length and a repeat of five to seven kelch motifs forms a β-propeller tertiary structure (26). Many members of this protein family, including SΔE-1/KLHDC8A before our study, have not been cloned or functionally characterized. In addition to the kelch domain, many superfamily members contain BTB (broad-complex, tramtrack, and bric à brac) or other conserved domains, whereas SΔE-1/KLHDC8A consists of seven kelch repeats and falls into a propeller structure-only subgroup. Several kelch proteins have been shown to associate with the actin cytoskeleton through their β-propeller structure or to colocalize with actin-rich organelles. Klhdc2, another propeller only kelch family member, has been reported to be highly expressed in muscle and is essential for myogenic differentiation and migration (27).

The gene encoding SΔE-1/KLHDC8A is located at human chromosome 1q32.1, a region where genomic amplification has been reported in gliomas (28). One cDNA microarray study, which analyzed nearly 20,000 genes, showed that SΔE-1/KLHDC8A/FLJ10748 is 1 of 50 genes whose increased expression was significantly associated with poor prognosis in glioblastomas (29). Consistent with qPCR results in our study, an examination of the cancer profiling databases, Oncomine (www.oncomine.org; ref. 23) (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/SAGE; ref. 24), show significantly higher expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A in high-grade glioma (P < 0.01; Student’s t test), as well as in medulloblastoma, prostate carcinoma, and invasive breast carcinoma, compared with normal tissues and other solid tumors (30 –33).

On the other hand, our survey of several routinely used glioblastoma cell lines has not shown appreciable baseline levels of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A expression, suggesting that expression of this gene is difficult to maintain in the conventional culture conditions of glioblastoma cell lines or that it is not needed for the growth of such cells in vitro. We also experienced decreasing SΔE-1/KLHDC8A expression during establishment of ΔEGFR-independent cell lines from xenograft tumors by using conventional growth conditions. This loss of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A expression during cell line establishment is reminiscent of the observation that expression of ΔEGFR itself is difficult to maintain during in vitro establishment of glioblastoma cell lines, while it is maintained in serially passaged xenografted tumors (34, 35). Analysis of the public database, Laboratory for Systems Biology and Medicine (www.lsbm.org), indicates that the expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A is high in fetal brain, cerebellum, thalamus, pituitary gland, ovary, and neuronal stem cells, whereas expression is low in other tissues such as normal adult brain and differentiated astrocytes. Taken together, the spatial expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A leads us to speculate that in addition to its role in tumor formation and maintenance, this molecule may play a pivotal role in the maintenance of the neural stem cell population.

Glioblastomas may use several mechanisms to evade therapies targeted at ΔEGFR or other receptors. The presence of redundant active tyrosine kinase receptors such as PDGFR, IGF1-R, and c-Met contributes in part to this resistance (19 –21), whereas increased expression of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A, or similarly acting molecules and their pathway interactions, might also play an important role. The heterogenous staining within tumors and across patients raises the possibility that such heterogeneity and potential resistance of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A cell subpopulations may contribute to eventual resistance of GBM patients to EGFR inhibition. Further studies using biopsy evaluation of SΔE-1/KLHDC8A expression pre- and posttreatment will be needed to evaluate this possibility. In summary, these studies point to the idea that targeting both the primary target and potential escape mechanisms might have better therapeutic results. Indeed, the utility of combination therapies targeting multiple pathways simultaneously has been reported (36) and suggests that this area warrants considerable further attention.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Biological Reagents.

The human high-grade glioma cell line, U373MG, was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. U373MG cells, which overexpress ΔEGFR, wild-type (wt) EGFR and control luciferase genes (Lux) were engineered as described (5, 6).

Engineering Tet-Regulatable ΔEGFR-Expressing Glioma Cells.

U373MG cells were first infected with the pRevTet-Off (Clontech) retrovirus and were selected in media containing neomycin (G418) to create a stable Tet-regulatable cell line. Approximately 20 independent clones were then isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and subsequently screened for high inducibility and low background by using the luciferase expressing pRevTRE-Luc virus. Four clones with high luciferase induction in medium without doxycycline and with effective suppression in medium containing doxycycline were selected. These clones were further tested, and a clone that was not tumorigenic in the absence of ΔEGFR expression in nude mice and possessed the same ploidy as parental U373MG, as assessed by FACS analysis, was chosen to establish doubly stable, ΔEGFR- and DK-inducible cell lines. To achieve this, the pΔCMV/(tetO)-ΔEGFR-IRES2-EGFP or pΔCMV/(tetO)-ΔEGFR DK-IRES2-EGFP vectors were cotransfected with a plasmid harboring a puromycin resistance gene into the tet-regulatable U373MG clone by calcium phosphate precipitation and cells were selected in medium containing puromycin. The pool of clones was then harvested and FACS sorted twice to enrich cells that had higher expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) when cultured in medium without doxycycline.

Xenografts.

For s.c. tumors, 2 or 3 × 106 U373MG cells in 0.1 mL of PBS were injected into the flanks of nude mice. To suppress the expression of ΔEGFR, mice were fed with water containing 1.25% sucrose and 0.5 mg/mL of doxycycline (Dox). Tumor volumes were defined as (longest diameter) × (shortest diameter)2 × 0.5. All of the procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California. Tumors were resected immediately after perfusion with 20 mL of cold PBS, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. Total RNA was isolated from frozen tumor samples using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

To establish secondary tumor cell lines from xenografts, resected tumor pieces were immediately stored in sterile, ice-cold PBS containing 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Tumor pieces were washed thoroughly in cold PBS and then minced. These tissue pieces were suspended in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin and seeded into Petri dishes. After 12 h of incubation at 37 °C, regular growth medium was added and contaminated mouse tissues were eliminated by culturing in medium containing puromycin.

For additional details, please see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GBM clinical samples were kindly provided by Dr. Ryo Nishikawa, Department of Neuro-Oncology, Saitama Medical University, Saitama, Japan. A.M. was supported in part by a fellowship from the SUMITOMO Life Social Welfare Services Foundation and the Paul Taylor/American Brain Tumor Association Fellowship. These studies were supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 CAO95616 (to W.K.C., F.F., K.L., and L.C.) and the Goldhirsh Foundation (F.F.). W.K.C. is a fellow of the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0914356107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Louis DN, et al. The 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 114. Lyon, France: IARC; 2007. pp. 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libermann TA, et al. Amplification, enhanced expression and possible rearrangement of EGF receptor gene in primary human brain tumours of glial origin. Nature. 1985;313:144–147. doi: 10.1038/313144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekstrand AJ, et al. Genes for epidermal growth factor receptor, transforming growth factor alpha, and epidermal growth factor and their expression in human gliomas in vivo. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2164–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugawa N, Ekstrand AJ, James CD, Collins VP. Identical splicing of aberrant epidermal growth factor receptor transcripts from amplified rearranged genes in human glioblastomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8602–8606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishikawa R, et al. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human glioma confers enhanced tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7727–7731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagane M, et al. A common mutant epidermal growth factor receptor confers enhanced tumorigenicity on human glioblastoma cells by increasing proliferation and reducing apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5079–5086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narita Y, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor signaling down-regulates p27 through activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in glioblastomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6764–6769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heimberger AB, et al. Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1462–1466. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinojima N, et al. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6962–6970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loew S, Schmidt U, Unterberg A, Halatsch ME. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme and other malignant neoplasms. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:703–715. doi: 10.2174/187152009788680019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmen SL, Williams BO. Essential role for Ras signaling in glioblastoma maintenance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8250–8255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin L, et al. Essential role for oncogenic Ras in tumour maintenance. Nature. 1999;400:468–472. doi: 10.1038/22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III mutations in lung tumorigenesis and sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7817–7822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510284103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RB, et al. Importance of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in establishment of adenomas and maintenance of carcinomas during intestinal tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1521–1526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellinghoff IK, et al. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lassman AB, et al. Molecular study of malignant gliomas treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: Tissue analysis from North American Brain Tumor Consortium Trials 01-03 and 00-01. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7841–7850. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich JN, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:133–142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camp ER, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakravarti A, Loeffler JS, Dyson NJ. Insulin-like growth factor receptor I mediates resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy in primary human glioblastoma cells through continued activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 2002;62:200–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang PH, et al. Quantitative analysis of EGFRvIII cellular signaling networks reveals a combinatorial therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12867–12872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stommel JM, et al. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases affects the response of tumor cells to targeted therapies. Science. 2007;318:287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan C, et al. High-resolution global profiling of genomic alterations with long oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4744–4748. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes DR, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lal A, Sui IM, Riggins GJ. Serial analysis of gene expression: Probing transcriptomes for molecular targets. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 1999;1:720–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B, Chang CM, Yuan M, McKenna WG, Shu HK. Resistance to small molecule inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor in malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7443–7450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams J, Kelso R, Cooley L. The kelch repeat superfamily of proteins: Propellers of cell function. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuhaus P, et al. Overexpression of Kelch domain containing-2 (mKlhdc2) inhibits differentiation and directed migration of C2C12 myoblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3049–3059. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riemenschneider MJ, et al. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM4 (MDMX) gene from 1q32 in a subset of malignant gliomas without TP53 mutation or MDM2 amplification. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6091–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Y, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals molecularly and clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma multiforme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5814–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun L, et al. Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freije WA, et al. Gene expression profiling of gliomas strongly predicts survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6503–6510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips HS, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finak G, et al. Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2008;14:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nm1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannini C, et al. Patient tumor EGFR and PDGFRA gene amplifications retained in an invasive intracranial xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:164–176. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humphrey PA, et al. Amplification and expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human glioma xenografts. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2231–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goudar RK, et al. Combination therapy of inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (AEE788) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (RAD001) offers improved glioblastoma tumor growth inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.