Abstract

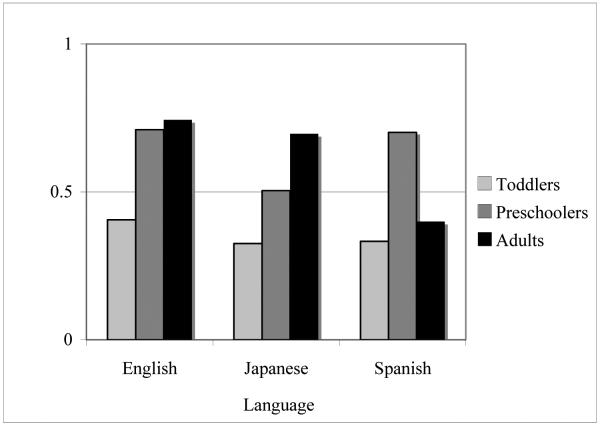

The world’s languages draw on a common set of event components for their verb systems. Yet, these components are differentially distributed across languages. At what age do children begin to use language specific patterns to narrow possible verb meanings? English, Japanese, and Spanish-speaking adults, toddlers, and preschoolers were shown videos of an animated star performing a novel manner along a novel path paired with a language appropriate nonsense verb. They were then asked to extend that verb to either the same manner or the same path as in training. Across languages, toddlers (2- and 2 ½-year-olds) revealed a significant preference for interpreting the verb as a path verb. In preschool (3- and 5-year-olds) and adulthood, participants displayed language specific patterns of verb construal. These findings illuminate the way in which verb construal comes to reflect properties of the input language.

Although relational terms such as verbs, adverbs, and prepositions are integral to language, they are harder to learn than object labels (Gentner, 1982; Bornstein, et al., 2004; Waxman & Lidz, 2006; Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2008). Verbs in particular are difficult to learn because any event includes a multitude of relations (Gentner, 2003). For example, the same event can be construed as an instance of swaggering, stepping, entering, coming, advancing, and smiling. Further, languages vary in terms of which components of an event are labeled (Gentner, 2006; Langacker, 1987; Talmy, 1985). For example, Turkish requires that the speaker use verb morphology to indicate whether speakers witnessed an event themselves or heard about it from another source (Aksu-Koc & Slobin, 1986), but languages like French and English do not. The existence of such language specific patterns of verb use requires that speakers attend to and encode different attributes of events. In this paper, we compare verb acquisition in children learning English, Japanese, and Spanish to uncover how early relational concepts and language interact to help narrow possible verb meanings in language specific ways. We hypothesize that children will initially show common, possibly universal verb construal, only later demonstrating language specific tendencies.

There is a core set of possible referents within events that are often encoded across languages (Jackendoff, 1983; Langacker, 1991; Maguire & Dove, 2008; Slobin, 2001; Talmy, 1985). The fact that these are “packaged” differently in different languages offers an ideal testing ground for questions of how language and early relational concepts interact. Two of the best-researched early relational components that languages differentially encode are path and manner (Talmy, 1985). “Path” refers to the course followed by a figure with respect to a ground object. Thus, the verb “circling” might be used in English to describe how a dog moves around a fire hydrant. “Manner” refers to the way in which the figure moves. For example, one might say, “The dog walked (or ran or scurried) around the fire hydrant.” Talmy (1991; 2000) categorized the world’s languages based on differences between these typologies. In “satellite-framed languages” (S-Languages) such as English, German, and Russian, manner is often encoded in the verb whereas path is commonly encoded in a satellite position such as a prepositional or adverbial phase (e.g., fly away). Conversely, according to Talmy, in Spanish, Japanese, Greek and other “verb-framed languages” (V-languages), path is most often mentioned in the verb and manner can be omitted. When manner is encoded, it often appears outside of the verb in prepositional or adverbial positions (e.g., leave flyingly). While these characterizations of languages are statistical rather than absolute tendencies (Slobin, 2006), sensitivity to the typology of one’s language could help limit the number of possible referents for a novel verb.

Cross-linguistic Typology for Path and Manner

Early interpretations of Talmy’s original classification of path and manner differences across languages placed S-languages and V-languages in stark contrast to one another, with verbs in S-languages encoding manner and verbs in V-languages encoding path. However, Slobin (2006) and others (Beavers, 2008; Naigles & Terazzas, 1998; Matsumoto, 1996) noted that the difference between S-languages and V-languages is not a straightforward dichotomy. Rather speakers of S-languages show a strong bias towards manner verbs, while speakers of most of the commonly researched V-languages, such as Spanish, French, Greek, and Turkish are equally likely to label the path or the manner of the motion using verbs. Thus, this difference in path and manner encoding may be best thought of as a continuum, with manner-biased S-languages, like English and Russian, at one end of that continuum, and many of the well-researched V-languages actually falling closer to the middle. To date, research on adult action verb production supports this claim. Speakers of S-languages, such as English and German, use more manner verbs than do speakers of most V-languages, such as Greek (Papafragou, Massey & Gleitman, 2006), Turkish (Slobin, 2003), and Spanish (Naigles & Terrazas, 1998; Naigles, Eisenberg, Kako, Highter & McGraw, 1998; Slobin, 2003). These languages use path and manner verbs with approximately equal frequency.

The manner bias in S-languages, marking the far end of the continuum, can be quite striking. For example, Naigles, Eisenberg, Kako, Highter and McGraw (1998) reported that in describing ten short video clips of events, Spanish-speaking adults were nearly equal in their use of path and manner verbs, producing an average of 3.83 path verbs and 4.58 manner verbs. English-speaking adults, on the other hand, produced a mean of 0.58 path verbs and 9.08 manner verbs! Thus English speakers produce more than 15 times as many manner verbs as path verbs. Across at least 11 languages (Slobin, 2006), adult production shows a similar pattern of a strong manner preference in S-languages and a near equal distribution of path and manner verbs in V-languages.

A manner/path asymmetry is also reflected in verb number. For example, English has been estimated to have several hundred manner verbs compared to Spanish’s approximately 75 (Slobin, 2006). Thus, speakers of English have many verb options to choose between to encode finer manner distinctions than in V-languages. The dramatic differences in the way languages encode events raises the question this paper addresses: Is there a developmental shift from a more universal to a more language specific construal of novel verbs?

The Development of Language Specific Typologies

Children appear to be sensitive to path and manner movements from a young age. In fact, Pulverman and Golinkoff (2004; Pulverman, Song, Pruden, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, under review) found that by 7 months infants could distinguish between changes in manner even if path remained constant as well as changes in path even if a manner remained constant. Interestingly, at 14- to 17-months, English and Spanish speaking infants were equally likely to notice path and manner changes in dynamic, non-linguistic stimuli (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2008; Pulverman, Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, & Sootsman Buresh, 2008). Closer investigation revealed that there are subtle relationships between nonlinguistic attention to path and manner changes and language development. Namely, even though no language was present in the task, English-speaking 14- to 17-month-olds who had high vocabularies based on parental report, were more sensitive to changes in manner than their lower vocabulary peers (Pulverman, 2005; Pulverman, Sootsman, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2003). In contrast, high vocabulary Spanish speakers were less sensitive to manner changes than their lower vocabulary counterparts. Thus attending to manner to a degree appropriate for one’s language may aid in early language acquisition.

The preference for producing manner verbs in S-languages compared to the near equal use of path and manner verbs in many V-languages begins at a very young age. Using elicited speech samples, Özçaliskan and Slobin (1999) reported the number of path and manner verbs in English, Turkish, and Spanish produced by children between the ages of 3 and 11 and adulthood. By the age of 3, for every path verb used, 8.25 manner verbs were used for English speakers. Turkish and Spanish speakers, on the other hand, used nearly equal numbers of path and manner verbs throughout the lifespan, similar to the Spanish adults studied by Naigles et al. (1998). Parallel developmental results were reported between English and French (Hickman, 2006) and English and Greek (Papafragou, Massey & Gleitman, 2006). Thus, at a young age, children are producing language specific verb patterns. Such findings raise two related questions. First, when do children notice the statistical patterns in verb encoding in their native language, and second, what is the influence of a language’s typology on verb construal?

Specific predictions about the influence of language typology on verb construal were suggested in Slobin’s (2001) concept of “typological bootstrapping” - based on the input, speakers of a language would formulate expectations for verb construal. In particular, Slobin (2004; 2006; and see Mandler, 2006) addressed how speakers of the S-language English should be influenced by the strong bias towards manner verbs compared to speakers of V-languages. English speakers should be more likely than their V-language learning peers to interpret new verbs as naming the manner element of an action. This is because English not only has more manner verbs, but also makes finer-grained manner distinctions. A new verb should prompt an English speaker to identify a new manner variation as the referent of that verb.

The clearest prediction following from typological bootstrapping is that children acquiring an S-language like English should be more likely to assume that a novel verb refers to a manner rather than to a path, and their peers acquiring a V-language like Spanish should not show this pattern. There is a second prediction that, if true, could greatly increase children’s ability to acquire new verbs. To the extent that a language falls on either end of the path-manner continuum, verb acquisition may be enhanced by allowing children to make predictions about a verb referent using typological bootstrapping with a mutual exclusivity strategy (Markman & Wachtel, 1988) to narrow the meaning of a new verb. In other words, children learning a language like English - an extreme manner language - might assume that a new verb names the manner of a new action even if that label is not explicitly paired with the action. This strategy is similar to the “shape bias” posited in noun learning that leads children to assume that a new noun refers to a new object, identified by a novel shape, as opposed to other features such as color (Imai, Gentner, & Uchida, 1994; Landau, Smith & Jones, 1988). As English is at the far manner end of the path-manner continuum, a new verb should refer to a new, previously unlabeled manner. This would represent a clear case of language typology influencing verb construal even in a non-ostensive labeling context.

To date only one study has specifically tested the influence of language typology on children’s verb construal and, surprisingly, the research suggests that children might not use language specific interpretations of verbs until relatively late. Hohenstein (2005) investigated how Spanish- and English-speaking 3.5- and 7-year-olds construe novel verbs in relation to path and manner. She showed children a video of an action containing a salient manner and path change and offered a novel verb (e.g “kradding”) presented either in a manner frame with the path in a prepositional phrase (e.g “Look, she’s kradding toward the tree”) or a path frame (e.g. “Look she’s kradding the tree”). These sentences were paired with a video of a woman skipping towards a tree, but not touching it. As a result “kradding” can refer to the manner, skipping, or the path, approaching. It was not until age 7 that differences based on native language emerged. In the manner-framed condition, English-speaking 7-year-olds were more likely than Spanish-speaking 7-year-olds to construe the verb as referring to the manner of the action. At the age of 3.5, children in both languages showed the same response pattern. Specifically, Spanish- and English-speaking 3.5 -year-olds were similarly influenced by the accompanying sentence frame, construing the verb as a path verb in the path-frame condition and as a manner verb in the manner-frame condition. Thus, at this age, the syntax of the sentence is quite influential in verb construal. The question remains: when does typological bootstrapping emerge when children are not given the aid of such definitive syntactic cues?

Here we investigate how native language influences verb construal from early in verb learning using a design similar to Hohenstein (2005) but with a less definitive syntax. In addition to studying English and Spanish, we included Japanese to study a fuller range of the path-manner continuum (Matsumoto, 1996; Slobin, 2004).

Japanese on the Path-Manner Continuum

Japanese provides an interesting test for the interaction of semantics and typology in language acquisition. Traditionally, Japanese has been classified as a V-language, in which the path is conflated in the main verb and manner is omitted or included in a satellite position (Slobin, 2004; 2006; Talmy, 1991). An interesting feature of Japanese, however, is that verbs commonly occur in a verb-verb matrix, in which the second verb is the main verb and the first verb is a subordinate verb. Often in describing both the path and manner of a motion event, the main verb expresses path, and the subordinate verb expresses manner (Allen et al., 2007). For example, “He rolled down the hill” is likely to be described in Japanese as “Korogat-te saka-o ori-ru”, which translates as while rolling (Korogat-te) the slope (saka) he/she/it descends (ori-ru) (Allen et al., 2007). In this case, both path and manner are described using verbs, however, the first verb (korogat-te) is considered subordinate to the main path verb (ori-ru). This use of verb-verb matrices still qualifies Japanese as a V-language according to Talmy (1991). His classification focuses on a sentence’s main verb and leaves open the possibility of other verbs as satellites (Allen et al., 2007; Beavers, 2008; Matsumoto, 1996; Slobin, 2004; 2006). Thus, although Japanese is a V-language, the question of how adults and children will construe ambiguous novel verbs remains unclear.

An additional attribute of Japanese that highlights the manner of an action is the use of mimetics (also called ideophones), a type of onomatopoeia used for actions. For example, “pyon-pyon” indicates hopping, and “yuu-yuu” is used for movement ‘with an air of composure’ (Matsumoto, 1996; Slobin, 2004). Mimetics are common in Japanese (Allen et al., 2007; Kita, 1997) and can be used as manner verbs when a light verb such as -shiteiru (doing) or -teiru (a tense/aspect/modality expression marking the progressive) is added to them. Using conventional mimetics, a large range of distinct manners can be conveyed. For example, Wienold (1995) lists the range of mimetics, which can be used with the verb “aruku” or “walk” to create fine distinctions of manner of motion including yochiyochi aruku (to toddle), yoboyobo aruku (to stagger), tobotobo aruku (to trudge along), and shanarishanari aruku (to walk daintily).

Mimetics are commonly used by both children and adults (Allen et al., 2007; Imai, Kita, Nagumo & Okada, 2008). In adult speech, mimetics surface predominantly as adverbs. For example, in describing a man rolling down the hill, a Japanese speaker is likely to combine the mimetic guruguru (rotate) with a manner verb, saying “Guruguru mawat-te ori-te” which translates to “he/she/it descends as s/he turns guruguru (rotatingly)” (Allen et al., 2007). In production, Allen et al. (2007) found that both adults and 3-year-olds produced a range of mimetics in various constructions when describing events with salient path and manner changes.

When adults speak to young children, however, it is common for mimetics to be used as a verb placed in front of a light verb like “suru.” In fact, Okada, Imai and Haryu (in preparation) found that when describing a scene with a salient path and a salient manner to children, Japanese-speaking mothers were 5 times more likely to use mimetics than when describing the same scene to an adult experimenter. Further, they often used the mimetics + suru construction in the situations in which adverbial mimetics would be used in the adult language.

Not surprisingly then, children use mimetics as verbs too. In a corpus study, Akita (2007) reported that the mimetics + suru constructions were frequent and productive in a 2-year-old Japanese child’s corpus. Imai et al. (2008) further demonstrated that, when a novel verb was embedded in the mimetic + suru construction (e.g., batobato-shi-teru), Japanese 3-year-olds were successful in generalizing the newly taught verb to a new instance of the same manner of action done by a different actor, while the same age children failed to do so when the newly taught verbs were presented in the conventional non-mimetic form (e.g., neke-tteiru). Thus, Japanese-speaking children are exposed to a wide range of manner verbs at a young age.

Given these verb-verb constructions and the use of mimetics, how would children learning Japanese (a V-language) construe a novel, ambiguous verb? If Japanese-speaking children rely on main verbs, they might exhibit a strong path verb bias. However, if children are also using the features of the subordinate verbs and are susceptible to the focus on manner created by the use of mimetics, they might exhibit a manner bias or an equal expectation of manner and path verbs in verb construal. As a result, Japanese provides an interesting test case for the influence of language typology on verb acquisition.

The Current Studies

To test language specific influences on verb construal we present English, Japanese, and Spanish-learning adults (Experiment 1), toddlers (Experiment 2) and preschoolers (Experiment 3) with a novel action performed by an animated starfish (Starry). The target action contains a salient manner and a salient path and is paired with a novel, language-appropriate nonsense verb (in English, “Look, Starry is blicking!”). After training, children are asked to “Find Starry blicking!” when given two different, simultaneous scenes on a split-screen television. On one side, Starry performs the same manner with a new path, and on the other side, Starry performs the same path with a new manner. If participants assume the verb refers to the manner of the action, they should differentially indicate the same manner with a novel path. If, on the other hand, they assume that the verb refers to the path, they should pick the same path with a novel manner.

To increase the likelihood of uncovering language specific differences in verb construal, the present study used a generic syntactic frame in each language. Hohenstein (2005) pitted two potentially influencing factors against one another, the child’s native language (either a V-language or an S-language) and syntactic frame of the sentence (either a path or manner frame) to see how each was influencing verb construal. Because the two different syntactic frames encouraged either a path response or a manner response, there was no explicit test of the influence of the native language without a specific biasing frame. The present study embeds the novel verb in a non-specific frame (“Look she’s blicking!”) across the languages, to limit the influence of grammatical cues. Based on Naigles and Terrazas’ (1998) work with English- and Spanish-speaking adults, a completely non-biased verb frame is not possible. The proposed sentence structure is more common with manner verbs than with path verbs in Spanish. However, this sentence frame should have less of a direct impact than in the sentences used by Hohenstein, therefore giving a more neutral test of language specific influences. To keep Japanese as similar as possible in this respect, the verb inflection “-teiru” was added to the novel verb. The verb inflection “-teiru” is similar to an English light verb, like “doing” and marks the progressive. Previous work has shown that by age 5, Japanese-speaking children can learn and appropriately extend a novel verb using this form (Imai, et al., 2008; Imai, Okada, & Haryu, 2005; see also Imai et al., 2008). A further benefit of this syntactic form is that it leaves no doubt that the novel word is a verb, without favoring a path or manner interpretation.

The current studies test specifically those ages that should show a developmental shift from a common (possibly universal) verb construal to early language specific patterns. Similar to the theory set forth by Gentner (2003), Maguire, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff (2006), Allen et al. (2007), and Mandler (2006), we propose that, regardless of native language, children start with similar conceptualizations and labeling patterns. As knowledge of their native language increases, children will diverge and responses will become more language specific. First, we hypothesize that English, Japanese, and Spanish adults will display different patterns of verb construal (Experiment 1). Second, based on the importance of path components in children’s vocabularies cross-linguistically and production data (Slobin, 2004), we hypothesize that toddlers will initially prefer to construe a novel verb as labeling the path of an action regardless of the language they speak (Experiment 2). We further hypothesize that by preschool, children’s responses will begin to diverge. They will use typological bootstrapping strategies in systematic, language specific ways (Experiment 3).

Experiment 1

Although differences in adults’ verb production between V- and S-languages are clear, differences in verb construal are sometimes influenced by grammar and specific events depicted in the particular experiment. Further, very little is known about Japanese regarding path and manner verb construal. Experiment 1 was performed to establish that our stimuli could elicit language specific differences between English and Spanish and to uncover Japanese verb construal patterns.

Method

Participants

English speakers

Thirty-five adult native-English speakers from a suburban area of a large US city participated. These adults accompanied children who participated in other studies in the lab.

Spanish speakers

Fifteen adult native-Spanish speakers were recruited from Spanish-speaking community centers in a large US city. Because the participants were from the US they could not be considered monolingual. However, they all lived and worked in the Latino community and reported Spanish as their primary means of communication in and outside of the home.

Japanese speakers

Twenty-three adult native-Japanese speakers from suburban areas surrounding a large Japanese city were recruited from the population of adults accompanying children who participated in other studies in the lab.

Procedure

The procedures were kept as similar as possible across laboratories. For the English and Japanese speakers the session took place in the room where the corresponding developmental testing occurred (Experiments 2 and 3). The rooms were relatively bare except for a chair 72 inches in front of a large television monitor. For Spanish speakers the session took place in a quiet room of a community center. Instead of a television monitor, a laptop computer with a 17-inch screen was used to display the stimuli. All participants sat in the chair directly in front of the television or computer monitor and the experimenter stood directly behind the chair to read the experiment script and record responses. In all cases the experimenter was a female, native speaker of the target language.

Materials

The logic of the design was to teach the participants a novel verb for a novel action and test for verb construal. The visual stimuli were adapted from Pulverman (2005; Pulverman, Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, & Sootsman Buresh, 2008). Throughout the experiment, the agent, an animated starfish, performed actions in relation to a ball that acted as a ground object. Four manners (jumping jacks, twist, bow, and spin) and 4 paths (over, under, circle, and past) were created for use across all of the experiments and are depicted in Tables 1 and 2. Because the circle path contains components of both the over and under paths, it could not be paired with either of these for the test trials. Thus, as seen in Tables 1 and 2, paths and manners were grouped to assure that they were paired with a distinct counterpart during the test trials. This resulted in 8 possible path/manner actions (Jumping Jacks Over, Jumping Jacks Under, Twisting Over, Twisting Under, etc.). Each participant learned only one verb action pairing. Thus there were 8 experimental conditions each including one of the eight possible actions. Each laboratory independently used random assignment without replacement for determining which condition participants would complete. Following this procedure, within each laboratory all 8 conditions (randomly assigned) had to be completed before a condition could be repeated with a new participant. This kept the number of participants who saw each action near equal ( +/− one person) within each population.

Table 1. Paths used in all Experiments.

| Path | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | |||||

| Over |  |

|

|

|

|

| Under |  |

|

|

|

|

| Group 2 | |||||

| Past |  |

|

|

|

|

| Circle |  |

|

|

|

|

Table 2. Manners Used in All Experiments.

| Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manner | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 |

| Group 1 | |||

| Jumping Jacks |

|

|

|

| Twist |  |

|

|

| Group 2 | |||

| Bow |  |

|

|

| Spin |  |

|

|

All auditory stimuli were presented by a female native speaker of the language standing behind the participant. The total length of the experiment was 1 minute 13 seconds.

The introductory phase familiarized participants with the agent of the action by providing a language appropriate name (“Starry”, see Table 4 for all translations). Starry appeared for 6 seconds first on one side of the screen and then on the other accompanied by, “Look this is my friend Starry! Starry is fun! Look at Starry.” The first side to appear was counterbalanced across subjects. In these clips, Starry performed a novel manner (stretch) across a novel path (across from left to right) neither of which was used again. As in the test trials, each image took up 40% of the television screen.

Table 4. Auditory Stimuli Presented Across Languages for Each Phase for Experiment 1.

| Phase | Language | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | ||

| English | This is my friend, Starry! Do you see Starry? Wow, it’s Starry! | |

| Spanish | ¡Mira! Es mi amiga Estrellita. Se llama Estrellita. Estrellita es divertida. |

|

| Japanese | Mite! Staarii dayo. Staarii ga iruyo! | |

| Salience | ||

| English | Look up here! What’s Starry doing? What’s going on up here? | |

| Spanish | ¡Órale! Mira aquí. ¿Qué hace Estrellita? ¿Qué pasa aquí? | |

| Japanese | Koko wo mite! Staarii wa nani wo shite-iru no kana? | |

| Training | ||

| English | Starry’s blicking! Do you see Starry blicking? Watch Starry blicking! |

|

| Spanish | ¡Mira! Estrellita está gupando. ¿Ves que está gupando? Estrellita está gupando. |

|

| Japanese | Staarii ga motto nekette-iru-yo. Staarii ga nekette-iru-no wo mite! Mada nekette-iru-yo. |

|

| Initial Test | ||

| English | Where’s Starry blicking? Do you see Starry blicking? Look at Starry blicking! |

|

| Spanish | ¿Dónde está Estrellita gupando? ¿Me puedes enseñar Estrellita gupando? ¿Dónde está gupando? |

|

| Japanese | Staarii ga nekette-iru-yo. Staarii ga neke-tte-iru no wa docchi? | |

The salience phase was included to make the experiment as similar to the toddler design (Experiment 2) as possible. Two images of Starry performing distinct actions (e.g., bow around the ball and spin past the ball) were shown simultaneously for 6 seconds with neutral language (i.e., “Look, what’s Starry doing?”) and were synchronized, such that they started and stopped at the exact same time. Because the paths are approximately the same length, the speed with which Starry traversed the path was the same. Order of display was fully counterbalanced across subjects, such that each video clip was the training clip an equal number of times. As a result, the video clip that acted as a manner-match for one participant was a path-match for another.

In the training phase, participants watched Starry perform a novel action (e.g., spinning around the ball) paired with a novel verb (“Look, she’s blicking! Do you see her blicking? Watch her blicking!”). The training phase consisted of one 6-second clip repeated four times with the repetitions separated by an attention getter (a 3-second video of a laughing baby). During each 6-second clip, the verb was repeated 3 times for a total of 12 verb labels across 24 seconds of exposure. In addition, during the “attention getter” before the first clip and between the four training clips the verb was repeated (“Yea! Blicking!”) because research suggests that verb labels that occur before the actions may increase the likelihood of acquiring the verb (Tomasello & Kruger, 1992).

The test phase was designed to examine how participants construed the novel verb. This phase used the identical stimuli as the salience trials. One side of the screen displayed Starry performing the same manner seen during training paired with a novel path (e.g., spinning past the ball); the other side showed Starry performing a novel manner with the same path from training (e.g., bowing around the ball). The experimenter asked participants to (“Point to Starry blicking! Where’s Starry blicking?”). If adults believed the novel verb referred to the manner of the action, they should point to the image of Starry performing the same manner shown in the training phase paired with the novel path (i.e., spinning past the ball). If, on the other hand, adults believed the novel verb referred to the path of the action, they should point to the image of Starry performing the same path from the training phase paired with the novel manner (i.e, bowing around the ball).

Results

Because this test only included one question per participant, a Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was performed on the number of adults who gave each type of response (path or manner) for each language (English, Japanese, and Spanish). This analysis revealed significant group differences, 2 (2, 72) = 5.62, p < 0.05. Follow up analyses indicated that the pattern of responses by Japanese adults did not differ significantly from English or Spanish; however, English and Spanish speakers’ responses were significantly different from one another, 2 (1, 49) = 5.25, p < 0.05. The percent of adults selecting each response revealed that manner was selected by 40.0% of the Spanish speakers, 69.6% of the Japanese speakers, and 74.3% of the English speakers. The analysis was further broken down to test whether the responses for each language were significantly different from chance in their distribution of path and manner construals. Japanese, 2 (1) = 3.52, p < 0.05 and English-speakers, 2 (1) = 8.53, p < 0.005 selected manner significantly more often than would be expected by chance alone. Spanish-speakers performed at chance levels.

Discussion

The goals of Experiment 1 were to see whether adult native speakers would make differential verb construals as well as to learn more about the nature of path and manner verb construal in Japanese. As expected, the adults differed in their verb construals, with the greatest difference being found between English and Spanish. These patterns follow those predicted for S- and V-languages in that English speakers were more likely to construe a novel verb as a manner verb and Spanish speakers were equally likely to construe the verb as a manner or path verb, with a trend towards path.

As predicted, the pattern of construal displayed by the Spanish speakers was significantly different from that of English speakers, and fit with the classification of a V-language (Talmy, 1985). On the other hand, this is a stronger preference for path than would be predicted given the ‘bare-frame’ syntax for Spanish, which had elicited a stronger than expected manner construal in Spanish-speaking adults in a prior study (Naigles & Terrazas, 1998). Because the Naigles and Terrazas study used nearly an identical syntactic frame as the one presented here, the most likely reason for the discrepancy between the results is the stimuli. The 2-dimensional events we showed may have made path stand out more starkly against the background than the 3-dimensional human events created by Naigles and Terrazas. A further difference was in the selection of the actions. As Naigles and Terrazas note, “the task primarily involved translating or finding synonyms for the novel verb among the verbs already known in each subject’s language” (pg. 365). Although the stimuli we used do not necessarily preclude this strategy, our goal was to create a measure of novel verb construal. These results seem to indicate that we accomplished that goal.

The tendency to give a path constural in Spanish is not wholly surprising given that in Spanish, verb production and construal can be influenced by features of the event such as whether the path is resultative (the figure begins or ends its motion at or from a specific location) and whether a boundary is crossed in the path (such as entering a house or jumping into a pool) (Naigles et al., 1998; Slobin & Hoiting, 1994). Although our stimuli did not force a path interpretation by crossing a strong boundary, the relationship between Starry and the ball may have biased speakers towards path in the expected language specific way. This claim is supported by the fact that only for those paths in which Starry changed sides relative to the ball, either in circling it or moving over and under it (3 of 4 novel actions), was the verb interpreted as a path verb. On the other hand, when Starry traversed a vertical path - the past path - Spanish speakers more often interpreted this as a manner verb. This is similar to the findings of Naigles et al (1998) who reported that in describing a vertical boundary crossing Spanish speakers typically used a manner verb. These findings indicate that our stimuli elicit a pattern of response in Spanish speakers similar to those previously reported and with more of a bias towards path construal than in English-speakers.

Although Japanese may be categorized as a V-language due to the prevalence of paths compared to manners in the main verb, the current findings indicate that the large number of manner distinctions provided in Japanese through the use of subordinate verbs and mimetics influences verb construal. The particular details of the language’s lexicalization pattern may be more important to consider in verb construal than the typological classification of the language as a V- or an S-language.

Notably, these findings highlight the fact that language typologies are based on statistical regularities and not stark all-or-nothing patterns (Pulverman, Rohrbeck, Chen & Ulrich, 2008). In none of the languages were adults uniform in their verb construals. However, commonalities within each of the languages did emerge. English adults, in particular, displayed the greatest amount of consistency in the predicted direction.

The fact that differential patterns emerged across the three languages encourages us to probe the question of when children begin to form language specific patterns in verb construal. It might be expected that children start from a similar, universal tendency, influenced by their perception of events (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2008). Alternatively, children might make different construals from the beginning of language learning, already influenced by statistical tendencies in the input.

Experiment 2

Two lines of research support the claim that children’s default verb construal will be to interpret a novel verb as labeling the path as opposed to the manner of an action (Maguire & Dove, 2008). The first is infants’ ability to recognize, categorize, and distinguish between paths earlier than manners (Pruden, Hirsh-Pasek, Maguire, & Meyer, 2005). The second reason to believe that children will initially construe a novel verb as referring to the path of the action is young children’s bias to talk about paths, even in S-languages. Slobin (2004) found that English-speaking preschoolers tend to be more descriptive about paths than manners in their overall production, though this is evident in their prepositions instead of their verbs. For example, instead of using the verb climb to describe a scene in a book in which a child climbs a tree, English-speaking preschoolers often use the “light verbs” go and get with strong path markers, such as go up into the tree, and get up on the tree. This linguistic focus on path in English is surprising given the sheer number of manner verbs in English. Here we test whether 2- and 2.5-year-olds learning English, Japanese, and Spanish make similar path construals or whether they are already using language specific patterns when acquiring a new verb.

Method

Participants

English speakers

Fifty native-English speakers from a suburban area of a large US city participated. Eighteen participants were excluded from analyses (specific criteria below), 14 for low attention, 2 for side-bias, and 2 for experimenter error. The final sample contained two age groups: 16, young 2-year-olds (ranging from 23.79 months to 25.36 months, M = 25.00; SD = .70) including 6 females and 10 males, and 16, 2.5-year-olds (ranging from 30.06 months to 32.82 months, M =31.86; SD = .82) including 6 females and 10 males.

Spanish speakers

Forty-one native-Spanish speakers were recruited in a middle-class city in Mexico. Ten children were excluded for the following reasons: 5 for side-bias, 3 for fussiness, 1 for parental interference, and 1 for equipment error. There were two age groups: 16, young 2-year-olds, (ranging from 23.77 months to 26.23 months, M = 24.97; SD = .74) including 7 females and 9 males, and 15, 2.5-year-olds (ranging from 29.77 months to 33.23 months, M = 31.63, SD = .83) including 7 females and 8 males.

Japanese speakers

Thirty-four native-Japanese speakers were recruited from suburban areas of a large Japanese city. Four were excluded for the following reasons: 3 for low attention and 1 for fussiness. The final sample included 15, 2-year-olds (ranging from 23.77 months to 27.00 months, M = 25.0; SD = 1.25) including 7 females and 8 males, and 15, 2.5-year-olds (ranging from 29.77 months to 32.00 months, M = 30.63; SD = .82), including 8 females and 7 males.

Specific exclusion criteria

Children were removed from the study for four reasons. The first was low attention. Attention was calculated by dividing the total amount of time children looked at the television screen throughout the video by the total length of the video. Attention to less than 65% of the movie was the criterion set for removal from the study. This criterion is similar to, but slightly higher than, that used in previous research. The use of a more stringent attention criterion was designed to account for any differences in attention that might be caused by a) inadvertent, extraneous variables present in the testing locations or b) differences in the children in each culture. The data did show that the children in the English-speaking sample had a lower level of attention to the stimuli overall and the inclusion of only those children with high attention levels attenuated any differences between the groups on variables unrelated to language level.

The second, a side-bias, was calculated by dividing the amount of time children watched the right hand side of the screen during the trials in which an item was presented on both sides (salience and test trials) by the total amount of video time during which two items were on the screen. If the number was higher than 75% or lower than 25%, that participant was removed. The third reason, fussiness, was determined if the child’s eyes were not visible due to movement or squinting, or if a child cried for more than half the testing session. Additional reasons for removal included parental interference (opening their eyes during testing) or experimenter or equipment error (e.g., starting video too early, failure to record the session).

Procedure

All children were brought by their parents to laboratories in their respective locations. Every attempt was made to keep the testing sessions as similar as possible. Each testing room was kept relatively bare except for a large television, or projection screen (Spanish sample), and a video camera used to record the participants’ responses. The participant sat on a parent’s lap in a chair centered approximately 72 inches away from the display screen.

Across laboratories, children were tested in the identical manner, using the video from Experiment 1 in the Intermodal Preferential Looking Paradigm (IPLP; Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, Cauley, & Gordon, 1987; Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 1996). This methodology is ideal for young children, because it places minimal demands on the participants. In making decisions about word meaning, young children need only respond by moving their eyes. Children sat on a parent’s lap, viewing a single television displaying two images. The parent’s eyes were closed to discourage parental influence. Using an inconspicuous video camera, experimenters recorded children’s visual fixation responses. In the classic use of the IPLP, the linguistic stimulus “matches” only one of the images. For example, a cookie might be on the right and a shoe on the left, accompanied by the carrier phrase, “Where’s the cookie?” spoken in child-directed speech. If the child understands the word “cookie,” she will look more to the cookie than to the shoe. This paradigm is effective in testing toddlers’ comprehension of novel and familiar nouns (Hollich, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff, 2000) and verbs (Golinkoff et al., 2002; Naigles, 1990; Naigles & Kako, 1993). In this case, we extend the use of the IPLP to determine which of the two event options the participant considers to be the best depiction of the novel target verb.

As in Experiment 1 each participant was only taught a verb for one of the 8 verb-action pairings, which was determined using random assignment without replacement within each age group within each laboratory. As a result for each age group in each language population there were equal numbers of participants learning a verb for each action plus or minus one. The auditory stimuli were produced and recorded by a female native speaker of the language in child directed speech and presented via the television. Instead of requesting a point (as in the adult study) the voice asked participants to “Look at Starry blicking! Can you find Starry blicking? Where’s Starry blicking?” As in the adult experiment, these sentences repeated the verb three times during the 6-second clip. Because the Spanish populations in Experiments 1 and 3 lived in Spanish-speaking areas of Dallas, Texas, the verbal stimuli were created to accommodate various dialects. The Spanish stimuli in this experiment however were created for this specific dialect spoken in this area of Mexico. As a result the training stimuli had slight variations (i.e., using the nonce word “mucando” which would be inappropriate in some dialects of Spanish in which it is phonologically similar to a swear word and using the name “Totó” instead of “Estrellita” for Starry). These variations make the stimuli more accessible for the specific Mexican population, but should have no influence on verb construal.

If children believed the novel verb referred to the path of the action, they should look more to the image of Starry performing the same path from the training phase paired with a novel manner (i.e., bowing around the ball). On the other hand, if children believed the novel verb referred to the manner of the action, they should look more to the image of Starry performing the same manner shown in the training phase paired with a novel path (i.e., spinning past the ball).

Coding and reliability

Coding of the amount of time the child looked either to the right, left, or center of the screen was performed off-line by a “blind” and experienced coder from a videotape using a hand-held timer (in the U.S. and Japan) or the computer program Habit 2000 (Mexico) which yields similar results. The coder also checked that parents’ eyes were closed during the experiment as a failure to do so would result in the removal of that subject’s data. Ten percent of the subjects were coded twice to test for inter-rater reliability and a different ten percent were coded twice for intra-rater reliability. For both reliability measures, all coders were correlated above .98.

Results

Traditionally, looking time data have been analyzed in one of two ways. One way is to compare raw looking time to each of the possible events seen during the test trials. For example, we would compare looking time to the same path seen during training (paired with a new manner) to looking time to the same manner seen during training (paired with a new path). We will refer to this analysis as raw looking times. The drawback of this method is that it does not account for possible salience differences between the paired videos that children might display, although many of these should be cancelled out with counterbalancing.

Another way to code the data is to compare the proportion of looking time to a particular “target” during the salience trial (when children should look roughly 50% of the time to each side) to the proportion of looking time to that same target during the test trials. Thus, using path as the example, two scores would be compared: the proportion of time children attended to path during the salience trial (attention to path/total attention to both events) vs. the proportion of time children attended to path during the test trial (attention to path/total attention to both events). We refer to this measure as salience vs test proportions. Here we analyzed the data using both measures, with the same pattern of results regardless of the measure used.

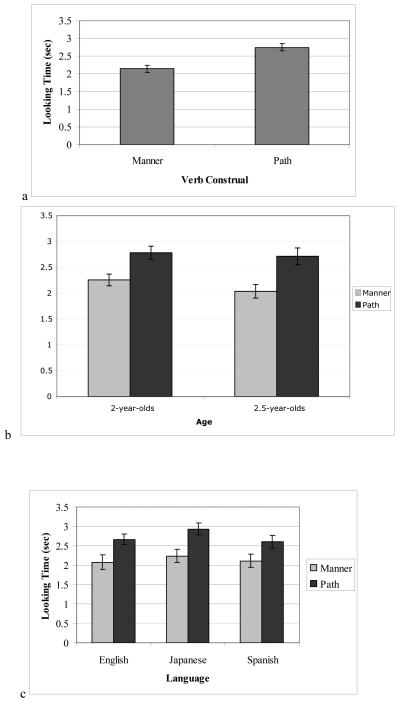

Raw looking times

To evaluate whether children construed the novel verbs as labeling either the path or the manner of the action, a 2 (age-group) × 2 (gender) × 3 (language) × 2 (event: old path vs. old manner) ANOVA was performed. These results showed no age, language, or sex main effects or interactions (all p’s > .5), but a significant main effect of looking time towards the same path compared to looking time towards the same manner at test, F(1, 94) = 12.80, p = .001. A paired-samples t-test revealed that toddlers attended to the same path option (M = 2.75, SD = 1.02) significantly longer than the same manner option (M = 2.15, SD = .87). Importantly, as seen in Figures 1a, 1b and 1c, these patterns held across languages and age groups.

Figure 1.

Toddler looking time for old manner + new path versus old path + new manner, 1a) displayed across age and language 1b) displayed by age; and 1c) by language.

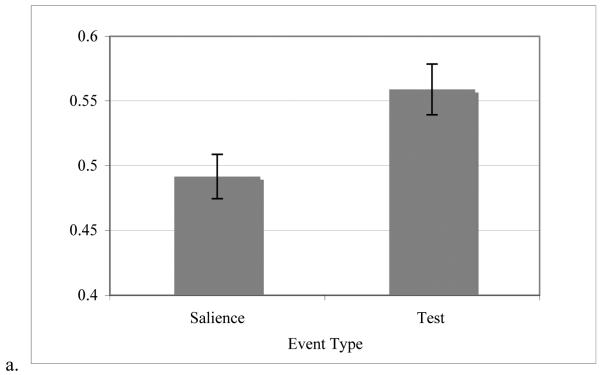

Salience vs. test proportions

A 2 (age-group) × 2 (gender) × 3 (language) × 2 (event: salience path vs. test path) repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to test for age and language differences in labeling preferences. As can be seen in Figures 2a-c, the results indicated no significant main effects or interactions with age, gender or language (all p’s > 0.05). A significant effect emerged between the proportion of looking time towards path during test compared to the proportion of looking time towards path during salience, F(1, 94) = 9.15, p < 0.005. A paired-samples t-test revealed a significant difference between salience and test proportions, t(99) = 2.88, p < 0.01 with significantly more of a preference for the same path during test (M =.56, SD = .17) than during salience (M = .49, SD = .19). These results were also consistent across ages and languages.

Figure 2.

Proportion of time looking towards the manner option during the salience trial and during the test trial 2a) across all ages and languages; 2b) between 2 and 2.5 years of age; 2c) across all languages.

Discussion

Experiment 2 compared how English, Spanish, and Japanese-speaking toddlers construe an ambiguous novel verb. We hypothesized that children would follow a similar pattern of verb construal - considering the novel verbs to be labeling the path component of the events - regardless of the language being acquired. As predicted, there were no significant differences between age groups or genders across languages as children displayed a preference for construing the verb as describing the path as opposed to the manner of the action, regardless of their native language.

One possible concern is that children may not have detected the changes in manner that were displayed in these actions. However, these same videos were used in a habituation paradigm with younger children who were able to differentiate changes in manner regardless of path by 14 months of age and changes in path regardless of manner by 10 months of age in non-linguistic discrimination and categorization tasks (Pruden et al., 2005; Pulverman et al., 2003; Pulverman, Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, & Sootsman Buresh, 2008). Such findings indicate that failure to detect manner is not likely to be the reason for path construal in this study.

It may be that the verb was construed as referring to the path because the path trajectory includes relatively more movement across the screen than the manner, thereby making it more salient. This is exactly as Gentner (2003), Mandler (2006), and Maguire, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff (2006) would predict and is the basis of the path argument. The fact that an agent’s path generally extends through a larger space than an agent’s manner may make the path component easier to individuate, categorize, and ultimately attach a verb to than the manner component of an action. Additionally, the lack of a salience preference for the particular paths of interest during the salience trials indicates that these paths were not more salient during the non-linguistic portions of the experiment, but were still more likely to be favored as the referent of the verb label.

By choosing English, Japanese, and Spanish, the current study examined typologically varied languages that fall in different places on the manner-path continuum. Nonetheless, this range does not include the strongest manner languages. Perhaps a language like Russian, which is one of the few known languages with an even stronger bias towards manner than English (Slobin, 2004), might have revealed a different pattern. While this is a possibility, the similarities in verb construal demonstrated across the three typologically varied languages tested here indicates that the bias to construe a novel verb as referring to the path of the action is strong in young children regardless of the specific language being acquired.

In the larger picture, these findings parallel those of Choi and Bowerman (1991; Choi, 2006; Hespos & Spelke, 2004) who demonstrated that across distinct languages, children appear to have some similar, possibly universal knowledge, such as containment, loose-fit, and tight-fit, which only later becomes language specific (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2008). Relatedly, this finding supports those of Pulverman et al. (2008; under review) who reported both path and manner discrimination in a nonlinguistic task by Spanish- and English-speaking 14- to 17-month-olds and 7- to 9-month-olds. In the current study, regardless of native language, 2- and 2.5-year-olds construed a novel verb as referring to the path of an action. Interestingly, in making a path attribution, English- and Japanese-speaking children go against their own language’s preference for encoding manners in verbs over paths as seen in Experiment 1.

The toddlers in Experiment 2 were in their second year with growing productive vocabularies. According to Slobin (2003), children are producing verbs in language specific patterns that match their language’s typology around the age of three. These results indicate that even by the age of 2.5, children do not seem to use their language’s typology to guide verb construal. When do children begin to utilize their language experience to construe new, ambiguous verbs in language-specific ways?

Experiment 3

Given the similarity in verb construal across such different language types in Experiment 2, and the differences in verb construal across the same languages by adulthood in Experiment 1, Experiment 3 investigated how these patterns may change during the preschool years. By that time, children’s production is already showing strong language specific differences in the use of path and manner verbs (Özçaliskan & Slobin, 1999). As a result, it seems likely that Slobin’s concept of “typological bootstrapping” in which children come to formulate expectations for linguistic expression in different ways based on the type of language they are learning (Slobin, 2001) may be at work in verb construals. If this were the case, children acquiring English should be more likely to assume that a novel verb refers to a manner than a path although their peers acquiring Spanish will not show this pattern. Given that a verb in Spanish has an equal likelihood of encoding path or manner, we predicted that children acquiring Spanish would not show a strong bias towards a path or manner construal. Similarly, although the Japanese-speaking adults in Experiment 1 construed the novel verb as a manner verb, the result was less consistent than among English-speaking adults. Perhaps this preference for manner may not occur as early in Japanese. Further, the predominance of path verbs as main verbs, which led to the classification of Japanese as a V-language, leads us to predict that Japanese-speaking preschoolers will not show a strong bias to path or manner construal.

As mentioned above there is a second prediction that follows from the use of typological bootstrapping in verb construal. When languages fall at the extreme ends of the path-manner continuum children may be able to use a mutual exclusivity strategy (Markman & Wachtel, 1988) to narrow the meaning of a new verb. Thus, seeing a new action, children learning a language like English might assume that a new verb, even one that has not been learned before, names the manner of the action, while children learning V-languages might assume that a new verb names the path of the action. If typological bootstrapping is to serve as an aid to verb construal, it should allow children to avoid making construals that are less likely to occur in the verbs in their language.

The idea of using mutual exclusivity (or a related strategy called “novel-name-nameless-category” - N3C, Golinkoff, Mervis, & Hirsh-Pasek, 1994) in verb learning is not novel. In fact, Merriman, Evey-Burkley, Marazita, and Jarvis (1996) and Golinkoff, Jacquet, Hirsh-Pasek and Nandakumar (1996) both reported that preschoolers use mutual exclusivity in verb learning, attaching a new verb to a previously unlabeled action over one for which they already have a verb. Both studies presented children with an unfamiliar verb in the presence of familiar and unfamiliar actions in either static pictures (Golinkoff et al., 1996) or videos (Merriman et al., 1993). Children assumed that the novel verb referred to the novel action over the familiar action by 34 months with static pictures and in video by 4 years of age (Merriman et al., 1993). These findings suggest that at around 3- to 4 years of age children could begin to profitably use mutual exclusivity as a verb learning strategy when their language has distinct encoding preferences. Thus, although unlikely to be observed in younger children, by preschool the path/manner bias might be strong enough to influence the construal of a novel verb. Therefore, the next logical question is whether typological bootstrapping, in combination with a mutual exclusivity strategy, allows children to home in on those components of action that are most likely to be encoded in the verbs of their language.

This argument suggests that English’s strong manner bias might cause English-speaking children to seek out novel manners as referents for new verbs, as predicted by Slobin (2006) and Mandler (2006). For Spanish-reared children, however, this would not be a practical strategy because in Spanish, a verb is equally likely to refer to a path or to a manner. Faced with this statistical ambiguity, Spanish-reared children may not show a clear mutual exclusivity bias. Predicting what Japanese-speaking children would do is difficult. If Japanese children show a strong bias toward manner construal like their adult counterparts in Experiment 1, they may display a mutual exclusivity strategy with a manner bias.

To investigate this question, two new test phases, (“new verb” and “recovery”, see Table 5) were added to the test trials used in Experiments 1 and 2. A new verb trial is visually identical to what is now called the initial test trial. On this new verb trial, instead of asking for the trained verb (say, blicking), the experimenter now presents a new verb, (e.g., “Where is Starry hirshing?”). If English-speaking children assume a novel verb refers to a novel manner, they should construe the new verb as referring to the novel action on the screen not yet named by a verb. They should switch from their initial response to selecting the other action. The following recovery trial, also visually identical to the previous two, asks the child to again select the original action (“Find Starry blicking!”), thereby confirming that their initial verb mapping was stable. Predictions for Spanish and Japanese-speaking children are less clear, but will likely be a function of the patterns observed in their initial verb construal.

Table 5. Test Trials with Video and Audio Presentations for Experiment 2 Presented in English; Earlier Phases of the Experiment including Salience and Training are Shown on Table 3.

| Phase | Visual Stimuli | Auditory Stimuli | Display Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Test Trial |

Where’s Starry blicking? Do you see Starry blicking? Look at Starry blicking! |

6 seconds | |

| Attention Getter |

XXX | Hirshing! | 3 seconds |

| New Verb Trial |

Find Starry hirshing. Do you see Starry hirshing? Look at Starry hirshing! |

6 seconds | |

| Attention Getter |

XXX | Blicking! | 3 seconds |

| Recovery Trial |

Where’s Starry blicking? Do you see Starry blicking? Look at Starry blicking! |

6 seconds |

Method

Participants

English speakers

Thirty-one participants from a suburban area of a large US city participated. There were 2 age groups: 14 three-year-olds, (ranging from 36.49 months to 47.79 months, M = 43.28; SD = 3.73) including 7 females and 7 males and 17 five-year-olds, (ranging from 60.16 months to 70.69 months, M = 63.51; SD = 3.54) including 8 females and 9 males.

Spanish speakers

Thirty-one participants were recruited from a Spanish-only preschool in a large US city. To assure that children were fluent in Spanish, a survey was sent to the children’s homes, in Spanish, asking what percentage of speech directed to the child in the home was in Spanish. Only children whose parents responded that 75% or more of the home language was Spanish were allowed to participate. In all, 23% indicated that only Spanish was spoken in the home. All of these children also successfully interacted in fluent Spanish with the experimenters who were native Spanish speakers.

This resulted in 31 participants across the 2 age groups: 16 three-year-olds (ranging from 37.20 months to 47.40 months, M = 41.04; SD = 3.35) including 10 females and 6 males, and 15 five-year-olds (ranging from 60.40 to 67.40 months, M = 63.76; SD = 2.15) including 11 females and 4 males. Both parents of the vast majority of the children (29) were originally from Mexico.

Japanese speakers

Thirty-two participants were recruited from suburban areas of a large Japanese city. All were monolingual Japanese speakers and most from middle to upper middle class. The sample included 16 three-year-olds (ranging from 36.0 to 48.0 months, M = 41.99; SD = 3.34) including 8 females and 8 males and 16 five-year-olds (ranging from 61.0 to 72.0 months, M = 64.75; SD = 3.22) including 8 females and 8 males.

Procedure

As in the previous experiments, all attempts were made to ensure that the testing was as similar as possible across sites. For English speakers, this experiment took place in the same room as the toddler studies, although the child was not accompanied by a parent. For Spanish and Japanese speakers, the experiment was conducted in a quiet area of a preschool classroom using a 17-inch screen laptop computer to show the displays. Because the screen is somewhat smaller on the computer than on the television, children were seated closer to the screen than to the television. In all cases, the experimenter stood directly behind the child. To keep the experiment as consistent as possible with Experiment 1, all auditory stimuli were presented by the experimenter in child-directed speech, reading from a script that was identical to the auditory presentation in Experiment 1, but for the two new trial types. Table 6 shows the script in English as well as the closely matched Japanese and Spanish counterparts. Similarly, as in Experiments 1 and 2, each participant was only taught a verb for one of the 8 verb-action pairings, which was determined using random assignment without replacement within each age group within each laboratory. As a result for each age group in each language population there were equal numbers of participants seeing each action plus or minus one.

Table 6. Auditory Stimuli Presented In English, Spanish, and Japanese for Experiment 3.

| Phase | Language | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Same as Table 4 | |

| Training | Same as Table 4 | |

| Initial Test | ||

| English | Where’s Starry blicking? Do you see Starry blicking? Look at Starry blicking! |

|

| Spanish | ¿Dónde está Estrellita gupando? ¿Me puedes enseñar Estrellita gupando? ¿Dónde está gupando? |

|

| Japanese | Staarii ga nekette-iru-yo. Staarii ga neke-tte-iru no wa docchi? | |

| New Verb Trial | ||

| English | Find Starry hirshing. Do you see Starry hirshing? Look at Starry hirshing! |

|

| Spanish | ¿Dónde está Estrellita lopiendo? ¿Me puedes enseñar Estrellita lopiendo? ¿Dónde está lopiendo? |

|

| Japanese | Staarii ga ruchi-tte-iru yo. Staarii ga ruchi-tte-iru no wa docchi? | |

| Recovery Trial | ||

| English | Blicking! Look at Starry blicking! Find Starry blicking! | |

| Spanish | ¿Dónde está Estrellita gupando? ¿Me puedes enseñar Estrellita gupando? ¿Dónde está gupando? |

|

| Japanese | Staarii ga nekette-iru-yo. Staarii ga neke-tte-iru no wa docchi? | |

Materials

The IPLP in Experiment 2 was modified to become a pointing paradigm. A pointing practice phase, to familiarize children with the methodology, asked them to point to particular images shown on the television. For example, when shown a dog and a cat on either side of the screen, they were asked to point to the cat. There were 3 pointing practice trials involving familiar objects and actions. Children’s pointing responses were recorded by the experimenter standing directly behind the child. Only children’s first response was tallied, though children rarely pointed to both stimuli within a test trial. During all trials the experimenter looked only at the child to refrain from giving any inadvertent cues. No child failed to reach the criterion of two or more correct responses in the training phase.

Similar to Hohenstein (2005) we did not include a salience phase for our older children, opting instead for pointing training trials as a measure of children’s ability to overcome any potential salience preferences to respond correctly. Children who did not respond correctly to two or more practice trials would have been removed from the sample but this did not occur. Further, a salience preference is less likely to influence the outcome of a response in a pointing paradigm, than in a looking time paradigm. Specifically, children are able to look at both items for as long as they like before making a pointing response.

Table 5 depicts the progression of test trials and Table 6 presents the linguistic stimuli for the three languages. For each trial, the child was asked up to 3 times during the 6-second clip to make a response. A row of 3 X’s shown for 3 seconds between trials served as a fixation point to maintain the child’s attention to the center of the screen. During this time, the experimenter also introduced the verb that would be the focus in the next trial (e.g, “Yay, blicking!”) because research suggests that a verb label occurring before the action may increase the likelihood of acquiring that verb (Tomasello & Kruger, 1992). During the test trials the experimenter recorded the child’s response online.

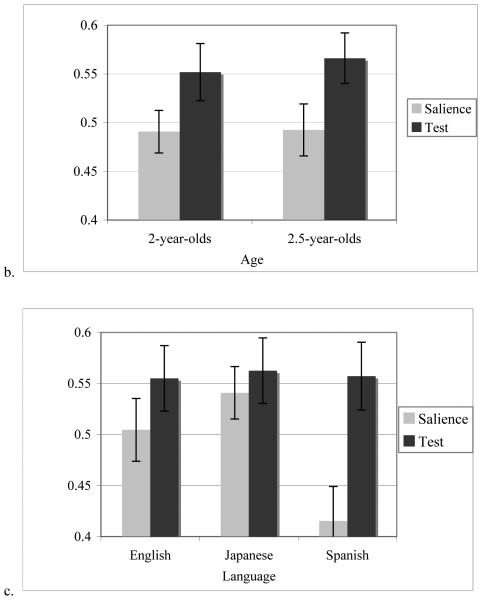

Results

Cross-linguistic patterns

Because the pointing response was a forced-choice paradigm and resulted in a categorical variable, non-parametric analyses were performed. Results are depicted in Table 7. Our initial question was whether children’s patterns of initial response and recovery differed by age and language. We performed a log-linear analysis for the 3 (language) × 2 (age) × 2 (initial construal) contingency table (Kennedy & Bush, 1988; Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991) on the initial test trial. The initial test trial revealed no significant differences, p’s > 0.25. However, given the subtlety of the effect in adults, differences in the pattern of responses might be revealed by investigating the patterns of responses displayed within each language.

Table 7. Number of Children by Language Group who Manifested a Manner Mutual Exclusivity Strategy (viz., initial manner construal followed by novel manner selection in the new verb trial followed by a return to initial manner on the recovery trial).

| Initial Test Trial Manner Construal |

New Label Trial Novel Manner |

Recovery Initial Manner |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| English (n = 31) | 22 ** | 21 | 21 *** |

| Japanese (n = 32) | 18 | 13 | 8 |

| Spanish (n = 31) | 22 ** | 16 | 11 |

| Number of Children in Each Language Group who Manifested a Path Mutual Exclusivity Strategy (vs., initial path construal followed by novel path selection in the new verb trial followed by a return to the initial path on recovery trial). |

| Initial Test Trial Path Construal |

New Verb Trial Novel Path |

Recovery Initial Path |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| English (n = 31) | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Japanese (n = 32) | 14 | 9 | 5 |

| Spanish (n = 31) | 9 | 7 | 4 |

p < .001.

p lt; .0001

Children’s initial construal of verb meanings

For English-speaking preschoolers, a Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was conducted comparing initial test response by age group (3- vs. 5-year-olds). Results indicated that there were no age group differences, p = .98. A chi-square comparing initial test response to chance showed that English-speaking children were significantly above chance in construing the novel verb as the manner of the action on the initial test trial, 2 (1, 30) = 9.09, p = .003). Children pointed to the manner extension 71.9% of the time.

For Spanish-speaking preschoolers, the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test revealed no significant differences between age groups. However, the analysis did reveal that Spanish speakers were significantly above chance in construing the verb as referring to the manner of the action, 2 (1, 31) = 10.08, p = .001, similar to English speakers. Children pointed to the manner extension 70.09% of the time.

For Japanese-speaking preschoolers, a Mann-Whitney non-parametric test found no significant differences between age groups. However, in this case, the children were not significantly different from chance in their construal of the novel verb, 2 (1, 32) = .50, p = .48, selecting the manner extension 50.40% of the time. Results for the initial test trials for all languages are depicted in Table 7.

Responses on the new verb trials

The next question was whether children followed a mutual exclusivity strategy in verb learning and, more specifically, if children whose language fell at a far end of the path-manner continuum were more likely to show this pattern in language predictive ways. If English speakers followed a manner mutual exclusivity strategy, they would select the event that contained the old manner on the initial verb trial, then select the opposite event that contained the new manner on the new verb trial, and finally return to selecting the original old manner on the recovery trial. If Japanese speakers followed a path mutual exclusivity strategy, they would select the event that contained the old path on the initial verb trial, then select the opposite event that contained the new path on the new verb trial, and finally return to selecting the original old path on the recovery trial. Thus, following a mutual exclusivity strategy meant that children chose one option at test; switched to the other option on the new verb trial; and returned to choose the original action on the recovery trial. Children who displayed this pattern across the three trials were categorized as using mutual exclusivity.

For the English speakers, of the 22 children who chose the manner construal of the verb on their initial test trial, 21 children appeared to use a mutual exclusivity strategy, a number significantly above chance by chi-square analysis, 2 (2, 22) = 14.75, p < .0001. Of the 9 children who initially chose the path construal of the verb, only 5 showed a path mutual exclusivity pattern, a number that was not above chance.

Spanish speakers were significantly more likely to select manner than path in the initial test trials. Of the 22 children who selected the manner construal event on the initial verb trial, only 11 showed a mutual exclusivity pattern, a number not significantly above chance by chi-square analysis, p > .50. Similarly, of the 9 Spanish-speaking children who selected the path on the initial test trial, only 4 showed a mutual exclusivity pattern (p > .50).

For Japanese speakers, of the 18 children who made a manner construal during the initial test trial, only 8 showed the mutual exclusivity strategy, p > .50. Of the 14 children selecting the path construal in the initial test trial, only 5 showed a mutual exclusivity pattern, p > .50. Table 7 displays the number of children who followed a mutual exclusivity strategy, both those with an initial manner construal and with an initial path construal, for each language.

We hypothesized that Spanish and Japanese children might struggle more than those learning English, but we were surprised that Spanish and Japanese speaking children did not follow mutual exclusivity at all. However, splitting the data based on initial response and within a language (i.e., only testing mutual exclusivity in the manner biased group and then separately in the path biased group for each language) caused us to lose much statistical power in evaluating the prevalence of children’s mutual exclusivity patterns. We next collapsed across initial response type, so that mutual exclusivity was counted as any “A- B-A” response pattern regardless of whether the first response was a manner construal or a path construal. This allowed us to investigate the use of mutual exclusivity in general. We performed a log-linear analysis for the 3 (language) × 2 (age) × 2 (use of mutual exclusivity) contingency table (Kennedy & Bush, 1988; Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991). A significant interaction emerged between language and age in the use of mutual exclusivity, 2 (7, 91) = 24.66, p < 0.001. Significant main effects of age and language were also uncovered, all p’s < 0.05. These differences can be seen in Figure 2. Five-year-olds were significantly more likely to follow mutual exclusivity than 3-year-olds, regardless of language. However, overall, English speakers used mutual exclusivity more consistently then Spanish or Japanese speakers.

Discussion

Experiment 3 investigated preschoolers’ construal of a novel verb in an ambiguous context that could refer to either a path or a manner, as well as how that verb construal pattern might influence the use of the mutual exclusivity word learning strategy. While the toddlers in Experiment 2 followed a similar pattern of verb construal regardless of the language they were acquiring, it was predicted that Experiment 3 would uncover language specific differences. Subtle cross-linguistic differences in initial verb construal patterns were uncovered. However, the secondary question of how language typology and verb construal may influence additional verb learning strategies revealed larger cross-linguistic differences.

As seen in English-speaking adults in Experiment 1, English-speaking preschoolers show a strong manner bias in the initial construal of a verb. Our second hypothesis was also confirmed: when presented with a second novel verb with no clear referent, children learning English chose the event that contained the novel manner as the referent of the novel verb. There are two explanations for this result. The first is that children are construing the novel verb as referring to the novel manner and the second is that children are construing the novel verb as referring to the old path. While the current results cannot fully distinguish between these two possibilities, children’s response patterns indicate that they are likely selecting the manner referent. Specifically, English speakers who initially made a manner construal followed a mutual exclusivity strategy in a consistent way, while those who initially made a path construal did not. It may be that only the children who reliably uncover English’s manner bias can exploit it to acquire more verbs. The children who initially made path construals may still be unsure about the nature of the language they are acquiring, which is why they fail to show a reliable mutual exclusivity strategy. This outcome is reminiscent of the findings of Pulverman et al. (2003) who examined 14- to 17-month-olds’discrimination of path and manner in nonlinguistic events. They reported that English-learning infants with above-median vocabularies attended more to manner than their lower-vocabulary peers, while Spanish-learning infants with above-median vocabularies attended less to manner than their lower-vocabulary peers. They argued that paying a language appropriate amount of attention to manner may help infants to find the referents of more verbs. Similarly in this study, the English-learning children who made initial manner construals appeared to have a better strategy for learning verbs in a language consistent way than those who did not choose manner.

Spanish-speaking preschoolers, similar to English speakers, construed the verb as referring to the manner of the action. This initial response by Spanish speakers may indicate that the syntactic frame is driving children’s verb construal. However, syntax would not explain the pattern of results across the new label and recovery trials. In an attempt to create a non-biased frame, we used a simple noun-verb frame (“Look, Starry is blicking!”) without additional adverbial or prepositional phrases. Although in Spanish this type of frame can be used for path or manner verbs, it is used more often for manner verbs (Hohenstein et al., 2004; Naigles & Terrazas, 1998). If the bare-frame had cued Spanish-speaking preschoolers to attend to and label the manner of the action, we would expect the new label and recovery trials to also elicit manner responses because of their bare-frames. This did not happen. Instead, the Spanish speakers performed less consistently than the English speakers on this additional task. As a result, syntax alone cannot explain this pattern. Furthermore, this pattern is the opposite of that found in Spanish-speaking adults, who should potentially be influenced by the syntax in the same way as the children.

What then, could be driving the initial verb construal in the Spanish-speaking preschoolers? These results may be highlighting the fact that Spanish-speaking children are at the crossroads of many competing cues. Spanish necessitates the coordination of multiple cues in verb construal, including the syntax of the verb frame (Hohenstein et al. 2004; Naigles & Terrazas, 1998) and the path type (Aske, 1989; Naigles, et al., 1998; Slobin & Hoiting, 1994). Each of these potential factors cues a different response, with the bare-frame leading to a manner construal as reported by Naigles and Terrazas (1998) and the path type leading to a path construal, as found in Experiment 1. To be sure at the earliest ages, based on Pulverman et al’s (2003) findings and our own findings in Experiment 1 there is an increased attention to path and a tendency to construe novel verbs as path verbs. However these findings indicate that by preschool, similar to the 3.5-year-olds in Hohenstein’s (2005) study, Spanish-speaking preschoolers appear to follow the cue provided by the syntax in their initial manner response, however, they tend not to follow through with the strategy to infer future meanings the way that their English-speaking counterparts do.