Abstract

Expectations, especially those formed on the basis of extensive training, can substantially enhance visual performance. However, it is not clear that the physiological mechanisms underlying this enhancement are identical to those examined by experiments in which attention is directed by explicit instructions rather than strong expectations. To study the changes in visual representations associated with strong expectations, we trained animals to detect a brief motion pulse that was embedded in noise. Because the nature of the pulse and the statistics of its appearance were well known to the animals, they formed strong expectations which determined their behavioral performance. We used white-noise methods to infer the receptive field structure of single neurons in area MT while they were performing this task. Incorporating non-linearities, we compared receptive fields during periods of time when the animals were expecting the motion pulse with periods of time when they were not. We found receptive field changes consistent with an increased reliability in signaling pulse occurrence. Moreover, these changes were not consistent with a simple gain modulation. The results suggest that strong expectations can create very specific changes in the visual representations at a cellular level to enhance performance.

1 Introduction

Directing attention to particular locations or objects can dramatically improve performance in perceptual tasks (Posner et al., 1980). In most studies of attention, cues are provided to instruct subjects where or how to direct attention. However, attention can also be directed according to expectations (Kurylo et al., 1996)(Downing, 1988)(Doherty et al., 2005 Sep 7). For example, in the case of spatial attention, if a change is particularly likely to occur at a certain location, then with sufficient practice, subjects will naturally direct attention to that location. Because subjects form such expectations in any well practiced or familiar situation, improvements in the specificity and allocation of attention may play a fundamental role in perceptual improvements observed with practice and training. However, because implicitly directed allocations of attention can be difficult to study and control for, we know relatively little about the physiological mechanisms underlying such allocations (Correa et al., 2006 Feb). Specifically, we do not know if the mechanisms that have implicated in previous studies of attention, such as a gain modulation of visual responses, are applicable in situations where subjects have strong expectations about the nature of the stimulus.

To address this issue, we studied the effects of attention on the receptive fields found in animals that deployed a consistent pattern of attention after extensive training. Specifically, we trained monkeys for several months in a visual detection task in which the likelihood that a brief motion pulse appeared varied systematically over time in a consistent manner (Salidis, 2001). To encourage the use of attention, the task was made challenging by embedding the pulse in high contrast motion noise. Because no explicit cues were given regarding the likely location of this pulse, attention could only be directed according to expectations based on task statistics. Animals formed appropriate strategies during training; their ability to detect very brief pulses improved, and the difference in performance between likely and unlikely pulses increased, with practice (Ghose, 2006). To study the changes in perceptual integration underlying this learning, we applied a behavioral reverse correlation (also termed “classification image”) analysis (Caspi et al., 2004) in which we averaged the motion noise stimuli preceding false alarm decisions. The analysis revealed that training refined the subjects’ spatiotemporal integration of motion signals. After training, subjects integrated motion over a timescale matched to the duration of the pulse, consistent with a nearly optimal filtering of visual information for the task (Simpson and Manahilov, 2001). Expectations played an important role in this optimization; temporal integration was considerably broader when pulse appearance was unanticipated.

This sharpening of temporal integration is particularly notable because it is discrepant from psychophysical (Eckstein et al., 2002) and physiological descriptions of gain-based mechanisms of spatial attention (McAdams and Maunsell, 1999a)(Salinas and Abbott, 1997)(Sripati and Johnson, 2006). In gain models of attention, attention increases the responsiveness of visual neurons without altering their selectivities (Ghose and Maunsell, 2008; Ghose, 2009). Of particular relevance to our motion pulse detection tasks, spatial attention in monkeys viewing random dot motion displays had gain-like effects on the temporal integration of neurons in middle temporal (MT) area (Cook and Maunsell, 2004), an area implicated by a variety of physiological studies (Britten et al., 1996)(Britten et al., 1992)(Shadlen et al., 1996) in the perception of motion. However, monkeys in this study were not presented with a consistently challenging task and were not required to sample brief epochs of motion information. Thus, they would not benefit from selective temporal integration and also had less need to consistently maintain a high level of attention. To examine whether these factors might produce a substantially different pattern of attentional modulation, we measured the spatial and temporal integration of MT neurons in our well trained animals while they detected brief pulses of motion. Receptive field measurements were done by applying a linear/non-linear (L-NL) model (Rust et al., 2006)(Sharpee et al., 2008) to the discharge observed during the motion noise that preceded the pulses. While attention uniformly altered gains, in many neurons significant changes in non-linearity were also observed. The combined effect of these changes was an increase in the signal to noise ratio of MT discharge. This suggests that implicitly directed attention in well trained animals can induce significant changes in the signaling capability of visual neurons beyond what would be observed with pure gain modulation.

2 Methods

2.1 Task Design and Training

Task design and training has been described previously in detail (Ghose, 2006)(Ghose and Harrison, 2009). Three monkeys (Macaca mulatta) performed a motion detection task. Animals were trained to perform a peripheral motion detection task in which they were required to respond rapidly to a pulse of coherent motion in one of two stimulus patches (Fig 1). Head position was stabilized by a chronic titanium head post implant secured with orthopedic screws. Eye position was monitored by a scleral eye coil and was recorded at 200 Hz. All surgeries were done under aseptic conditions and full anesthesia in accordance with the animal care guidelines of the University of Minnesota and the NIH.

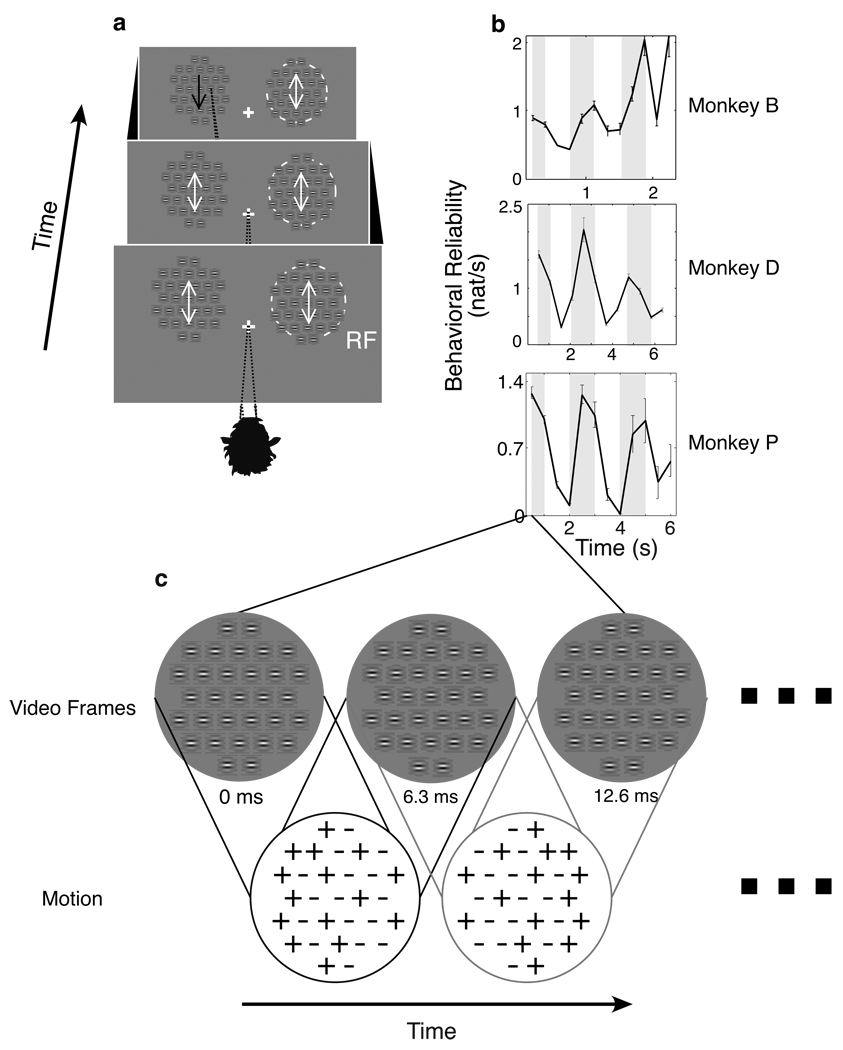

Figure 1.

Monkeys detected a coherent motion pulse which was embedded in a random motion stimulus. Two arrays of Gabors were presented, one of which was centered on the MT receptive field under study (a). Monkeys were required to maintain fixation during motion noise (white arrow) and saccade immediately to the location of a randomly presented motion pulse (black arrow). The likely location of pulse appearance varied systematically in time so that during that first second, if a pulse appeared, it was more likely to appear within the RF, while during the second second, the likely location was opposite to the RF (dark shading, a). This schedule had strong effects on performance: RF pulse detection was much better (b) when the pulse was likely to appear within the RF (gray shading, b). The motion noise presented prior to the pulse consisted of Gabors whose sine wave modulation was independently shifted in phase upon every frame update (c). Because the Gabors were oriented according to the preferred orientation of the neuron under study, positive phase changes corresponded with local movement in the preferred direction; negative phase changes, movement in the anti-preferred direction. Global motion, defined by the spatial average of these local movements, was close to zero throughout the stimulus.

Trials began with a fixation point (0.1 deg) appearing at a central location of a CRT placed 57 cm in front of the animal. Five hundred ms after the animals fixated upon this dot, a motion noise stimulus appeared at two locations. Animals were required to maintain fixation within a 1.5 deg square window while these motion noise stimuli were present and only break fixation immediately after a brief motion pulse (duration 63–83 ms) appeared at one of the locations. Although the timing of motion pulse presentation within each trial was randomized, the statistics of pulse appearance were kept constant. For any moment of time within a trial, the pulse was likely to occur over one patch (p=0.95–0.98) and unlikely to occur over the other patch (p=0.02–0.05) (dark panels, Fig 1a). This likelihood varied over time with a square wave modulation. Two temporal frequencies were used for the square wave: 0.5 Hz and 1.33 Hz. To avoid fluctuations in overall vigilance, the task design was counter-balanced within individual trials; during certain periods of time relative to motion noise onset, pulses were likely to happen at one location, while at other periods of time, pulses were likely at the alternate location. For all trials, the initial likely location of pulse occurrence was in the receptive field of the neuron under study. The consistent frequency and phase of the spatiotemporal probability modulation allowed the monkeys to form expectations about the likely location of a pulse at any point in time within the trial. Moreover, because the duration and direction of the pulse was kept fixed during recording, animals could also form strong expectations about the nature of the stimulus to be detected.

2.2 Visual Stimulus

Stimuli were two arrays (spanning 5–7 deg) of small 100% contrast achromatic patches (31 Gabors, 1 cyc/deg SF, sigma=0.25–0.5 deg) containing luminance modulated sine waves of identical orientation (Ghose, 2006). One array was centered on the receptive field of the neuron under study, while the other array was placed at a symmetric location (equal elevation, opposite azimuth) with respect to the vertical meridian (Fig 1). The inter-element spacing was scaled according to eccentricity (mean MT eccentricity = 10 deg). Although the phase of the sine wave within each Gabor was varied independently, the Gaussian envelopes of the Gabors were fixed. Sine wave phases for every Gabor were updated on every frame refresh (120 Hz monkey P, 160 Hz monkeys B and D). Motion noise was produced by randomly and independently stepping the phase within each patch (+/− 90 deg at 120 Hz, +/− 72 deg at 160 Hz) (white arrows, Fig 1) and coherent motion was introduced by briefly (63–83 ms) enforcing a consistent phase change across all patches (motion pulse, black arrows, Fig 1). Local temporal frequency and velocity were therefore constant (30 deg/s and 32 deg/s). Every Gabor was oriented according to the preferred orientation of the MT neuron and the direction of this coherent motion was set in accordance with the preferred direction of the neuron.

For all neurons within the same animal, identical random sequences were used to generate the motion noise. These random sequences described the relative motion of the 31 Gabors for 2^18 frames. Most trials contained a single motion pulse that was presented according to the aforementioned spatiotemporal schedule. However, approximately 5% of trials were catch trials, in which no motion pulses were presented at either array location, and the animals were required to maintain fixation throughout the trial. Progress through the random sequence was interrupted on all trials except successful catch trials by either an eye movement or the introduction of a motion pulse. The sequence position at which a pulse or eye movement occurred within each trial was recorded and used as the random sequence starting point for motion noise in the following trial. Thus, the actual sequence describing motion noise was unique for each trial of a given cell, with the exception of a small percentage of trials (2%) in which the sequence was sampled from its beginning.

2.3 Recording

All stimuli were retinally stabilized to reduce the influence of small fixational eye movements on neuronal activity (Gur and Snodderly, 1997; Bair and O’Keefe, 1998) and behavioral performance. Eye position was calibrated throughout experimental sessions using the eye positions measurements obtained after the animal fixated on one of 4 points separated by 1 degree around the center of the screen. Stabilization was accomplished by shifting the Gabor arrays, but not the fixation point, according to the most recent eye position sample after calibration. Behavioral control, visual stimulation, and data acquisition were computer controlled using customized software (http://www.ghoselab.cmrr.umn.edu/software.html). We recorded well isolated single neurons using standard extracellular recording techniques and digitized the occurrence of action potentials and CRT frame updates (1 kHz, monkey P, 10 kHz, monkey B). Area MT was identified physiologically by the presence of audible low-frequency (<100 Hz) local field potential responses to the motion noise stimulus, a high proportion of direction selective responses, and receptive field mapping. For each neuron, receptive fields were localized while the monkeys performed the same motion pulse detection with a single Gabor array whose position varied from trial to trial.

Once an optimal position was found, direction selectivity was assessed by recording responses to relatively long (167 ms) motion pulses of 8 different directions while the monkey performed the motion pulse detection task. On the basis of these tuning runs, a specific stimulus location and direction was chosen for extended recording. Discharge from motion noise in the extended recording session was used for this paper. The recording session was concluded when the entire random sequence had been presented or when the cell was no longer well isolated. Typical sessions lasted for around 30 minutes and contained hundreds of trials (mean=562) with an average trial duration of 1.5 to 2.5 seconds.

2.4 Behavioral Analysis

To measure the behavioral effects of training with a consistent schedule of pulse likelihood we applied an information theory metric that quantifies the statistical relationship between motion pulses and behavioral choices (Ghose and Harrison, 2009). In this metric, contingency tables between the stimulus (noise and pulse) and behavior (fixation and saccade) were formed by parcelling trials at different temporal resolutions (4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 ms). For each temporal resolution, tables for a variety of delays (4–512 ms) between stimulus and behavior were computed. Both the visual stimulus and the behavioral response were treated as point processes, so that the onset of a motion pulse or a saccade anywhere within a bin incremented the corresponding location within the table. Thus, by resampling all recorded observations we obtained a 2×2 contingency table between the stimulus and behavior for each delay and temporal resolution. These tables were used to compute mutual information which quantifies the reduction of uncertainty or entropy that arises from simultaneous observation of stimulus and behavior. This information quantity was then normalized according to the temporal resolution of parcellation to yield an information rate. All information rates were compensated for positive bias (Roulston, 1999) and confidence measures based on sample size were computed. The final product of this process is an “information surface” showing how information rate changes over time (delay) and temporal resolution for each epoch. In almost all cases a single peak is observed, describing a single combination of delay and resolution for which the relationship between the stimulus and behavior was the most consistent. We define behavioral reliability as this peak information rate.

Because a consistent schedule was used with the animals, we would expect this behavioral reliability to be modulated over the course of the trial in accordance with pulse statistics. As detailed in another manuscript (Harrison and Ghose, unpublished observations), this is indeed the case: behavioral reliability, defined on the basis of within-RF pulses and toward-RF saccades, was much higher when the pulse was likely to occur within the RF. To examine the dynamics of this modulation, we separately analyzed observations grouped into epochs relative to stimulus onset. We defined each epoch’s duration according to the temporal frequency of the schedule used in animal training; for the 0.5 Hz schedule, epochs were 500 ms in duration, while for the 1.33 Hz schedule, epochs were 188 ms in duration. Thus, within-RF motion pulses were likely in the first two epochs and unlikely in the second two epochs. Behavioral reliability was assessed for each epoch, yielding a description of how well performance tracked the changes in pulse probability over time within the trials.

2.5 Receptive Field Analysis

Discharge following motion noise onset, but prior to any saccades or the appearance of a motion pulse within the receptive field, was used for receptive field measurements. Because the Gabor elements were oriented so that the direction of the motion pulse corresponded with the preferred direction of the neuron under study, motion noise consisted of two types of local (within element) motion: preferred and anti-preferred. We characterized the motion occurring between specific adjacent video frames with a 31 element vector of +1 and −1, with each element corresponding to the phase increment or decrement of a specific Gabor within the array. To compute a linear estimate of the receptive field, we solved an overdetermined linear equation relating this stimulus description to neuronal discharge through regression (Cook and Maunsell, 2004)(Di-Carlo et al., 1998). Specifically, we defined an equation relating the number of spikes observed within a particular video frame with the motion sequence of the 30 previous video frames (corresponding with 250 ms for 120 Hz, and 188 ms for 160 Hz). This equation therefore has 31×30 coefficients, with each coefficient relating the strength of the relationship between discharge and motion occurring at a particular Gabor location and interval in time. To incorporate spontaneous activity, as well as responses due to factors such as contrast and orientation that were constant throughout the trials, we also included a constant in the equation, yielding a total of 931 coefficients to be determined. This constant term therefore defines baseline activity. Typical recording sessions included hundreds of thousands of frames and tens of thousands of action potentials.

In many of our linear receptive field estimates, high kernel coefficients were only observed for specific positions within the array. We therefore did not perform any smoothing or filtering in the spatial dimension. However, because of the fast frame rates employed in our study, we did smooth in the temporal dimension (Gaussian of 10 ms width) to reduce noise. Because there is a well defined response latency in MT neurons (Cook and Maunsell, 2004), kernel coefficients with very low latencies (<50 ms) reflect noise. To characterize the variability and noise of individual coefficients in the linear kernel, we therefore computed the standard deviation among the coefficients corresponding to the first six frames of the linear kernel (31×6=186). Only neurons whose linear kernel contained coefficients that exceeded this noise estimate by at least a factor of three (S/N>3) were included in our analyses. Estimates of receptive field size and total kernel power were based only on those kernel coefficients that exceeded this criterion. Receptive field size was defined by the number of elements meeting this criteria, while kernel power was defined by the root mean square (RMS) of all coefficients in the kernel that exceed the criterion.

While this procedure derives a maximum likelihood estimate of the linear kernel relating local motions to discharge, it does not take into account the known deviations from linearity of MT neurons (Britten and Heuer, 1999). To quantify this non-linearity, which has often been described by a power law relationship between neuronal input and output (Chichilnisky, 2001)(Nykamp and Ringach, 2002), we generated a linear prediction of the discharge expected for every video frame of the experiment. This was computed by multiplying the linear kernel with the preceding stimulus sequence. We then compared that prediction with the actual discharge observed. We did this by binning predicted and observed activity according to the value of the prediction and computing averages within each bin. Twenty bins were used. Because the distribution of linear motion predictions reflects the statistics of the motion noise, high and low predictions of activity within a frame are infrequent because they correspond with preceding episodes of relatively strong coherent motion in either the preferred or anti-preferred direction. To avoid poor sampling of such strong and weak predictions, we defined the bins so that they contained a roughly equal number of observations. The non-linear fitting algorithm within MATLAB was used to reveal the power-law coefficients relating the linear estimates of activity to actually observed activity. Confidence intervals for these coefficients were obtained by fitting non-linear functions to bootstrapped samples of the averages within each bin. Because the non-linear equation has two free parameters (gain and exponent), as opposed to the single free parameter of a linear relationship, for each neuron an F-test was used to evaluate whether the improvement in fit was significant.

To examine how receptive fields change with attention, we repeated this linear/non-linear (L-NL) procedure for specific subsamples of each neuron’s data. Kernels and non-linearities were computed on the basis of epochs in which behavioral performance was particularly high or low. This was assessed by sorting the epochs according to behavioral reliability.. Because RF detection performance tracked the cyclical modulation of RF pulse probability over time, the measures of adaptation and attention were counter-balanced: unattended and attended epochs were usually in equal proportions in the early and late parts of the trial. However, because the instantaneous probability of pulse appearance at either location decayed exponentially, shorter trials were more numerous than longer trials. This creates a potential sampling bias because epochs early within a trial are far more common than late epochs. To compensate for this bias, the number of frames presented throughout the entire recording session was tabulated according to epoch. On this basis, epochs sorted according to behavioral reliability were grouped together into three groups with approximately equal numbers of stimulus frames. Attended epochs were defined as the third with the highest reliability, while unattended as the group with the lowest reliability. For example, because of the initially high probability of the pulse appearing within the RF after stimulus onset, the attended group of epochs often contained the very first epoch, which was also the most common epoch. Therefore, in order to roughly equalize the number of frames in the attended and unattended epoch groups, a slightly larger number of epochs was usually incorporated into to the unattended group.

Although these procedures define the best L-NL model relating local motion signals to neuronal discharge, they do not quantify how good that model is. Typically, this type of model has been evaluated by comparing predictions about average stimulus selectivity with independently made observations (Cook and Maunsell, 2004)(Rust et al., 2005)(DeAngelis et al., 1993). For example, in the case of MT, a linear kernel with coefficients describing sensitivity to different directions of motion might be compared with the average responses observed to coherent motion in different directions. Such comparisons are based on averaging discharge, for example, to coherent motion, over many milliseconds or seconds. For this study, we chose a much more rigorous standard: the ability to predict the relationship between mean firing rate and stimulus strength used to evaluate non-linearities. The same method used to compute non-linearities was employed to evaluate the accuracy of these predictions. First, we computed linear kernels and non-linearities using the aforementioned methods applied to a random sampling of 90% of trials. We then convolved the stimulus sequence of the remaining 10% of trials with this linear kernel to generate a linear estimate of discharge on a frame-by-frame basis. The non-linearity from the 90% trial sample was then applied to predict actual spike discharge, and predictions were binned according linear estimate strength. The procedure yields a prediction of the average discharge expected given a certain motion strength, which can then be compared with the observed average discharge seen with that motion strength. Errors in this prediction were then normalized by the variance across bins. The method therefore tests how accurately the linear kernel and non-linearity derived from the 90% sample is able to predict discharge in the remaining 10% of trials. . We also used this method to study different models of receptive field dynamics. For example, receptive field changes associated with attention or adaptation might arise from either changes in the linear kernel, changes in the non-linearity, or changes in both. To measure how well a dynamic linear kernel paired with a static non-linearity explains experimental observations, we generated activity predictions using kernels computed using epoch subsamples with the overall power-rule derived from using all observations. Conversely, the dynamic non-linearity model was based on pairing the power-law coefficients derived from the subsamples with the linear kernel derived from all observations.

3 Results

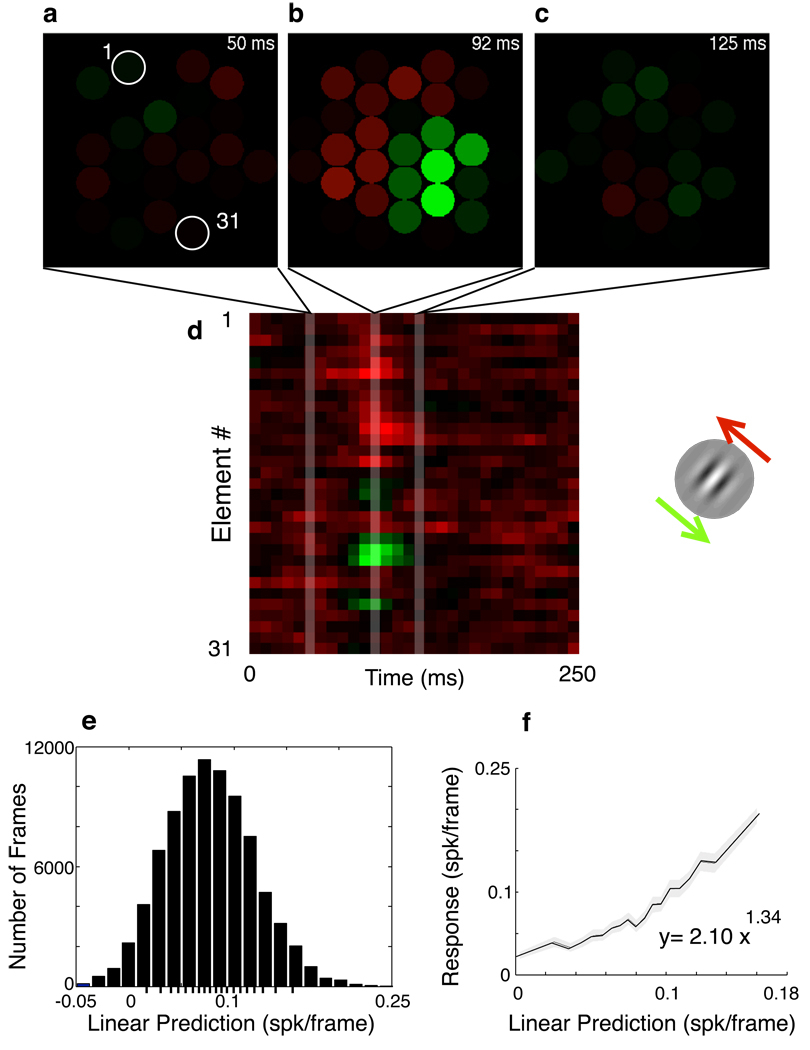

We trained three animals to localize a coherent motion which was embedded in high contrast motion noise. Animals were required to saccade to the location of this motion within 550 ms of its appearance. We recorded from a total of 74 MT neurons while the animals were engaged in the detection of this coherent motion (motion pulse), in which an array of elements briefly moved in a direction consistent with the preferred direction of the cell under study. All discharge prior to motion pulse appearance was correlated with motion noise to derive receptive field estimates. Receptive field estimates were computed by applying regression analysis to form a linear model relating local motions within the noise to spike discharge from the neuron (Fig 1c). These estimates describe the spatiotemporal sensitivity of the neurons to brief local movements in the preferred and anti-preferred direction. From this analysis, a total of 41 neurons had linear receptive fields whose peak magnitude exceeded our noise criterion. Twenty seven of these neurons were recorded using a video frame rate of 120 Hz, while the remaining were recorded using a frame rate of 160 Hz. Non-linearities were quantified by fitting how average firing rate varied as function of the prediction of discharge based on the linear kernel. Of these 41 neurons, 40 neurons were significantly non-linear in that a two parameter non-linear model was better able describe the variation of firing rate with stimulus than a purely linear model (F-test, p<0.01).

Temporal receptive field properties were largely consistent among the kernels: peak sensitivity, where preferred motion had the strongest effect on discharge, was usually observed at latencies from 67 to 91 ms, and the temporal extent of the kernels were typically around 67 ms (Fig 2). In most neurons, sensitivity to anti-preferred motion was observed at locations and latencies different from that of the peak, but this sensitivity was always significantly lower than the peak.

Figure 2.

Linear spatiotemporal map of the motion sensitivity of an example MT neuron. Regression analysis was used to relate local frame-by-frame movements (Fig 1c) to spike discharge. Discharge was associated with preferred direction motion (green) at specific locations within the array as well as anti-preferred motion (red) at other locations (b). The temporal envelope over which motion energy was summed was around 3 frames or 25 ms (d). Motion prior to this window (a) or after it (c) had little effect on discharge. A spatiotemporal map is constructed in which the particular Gabor element number (1 on upper left, 31 on lower right) defines the spatial axis (d). A prediction of activity within each video frame is derived by convolving the stimulus sequence preceding every video frame with this linear kernel estimate (e). The distribution of these linear predictions is divided into 20 bins, so that each bin has an equal number of frames. The average of observed activity within each bin is plotted versus the average of predicted activity to quantify systematic deviations from linearity (f). A nonlinear curve is then fit that describes the non-linear transformation necessary to explain neuronal discharge. Shading indicates 95% confidence regions.

To look for changes in the receptive fields of single neurons, we repeated the analysis by subsampling motion noise during specific periods of time within the trials. Each trial was divided into epochs of analysis according to the schedule used in training the animals. The schedule, which was maintained throughout the recording sessions, included consistent and periodic shifts over time in likely location of a motion pulse which the animal was required to detect. Two schedules were used in which only the temporal frequency of the probability shifts was varied: 0.5 Hz and 1.33 Hz. To examine the effects of attention, we separately analyzed those epochs in which detection performance was high and those epochs in which performance was low. Attention and time within the trial were poorly correlated because performance fluctuations were highly correlated with the cyclical probability schedule. Therefore, epochs of good and bad performance were equally likely early and late within the trials.

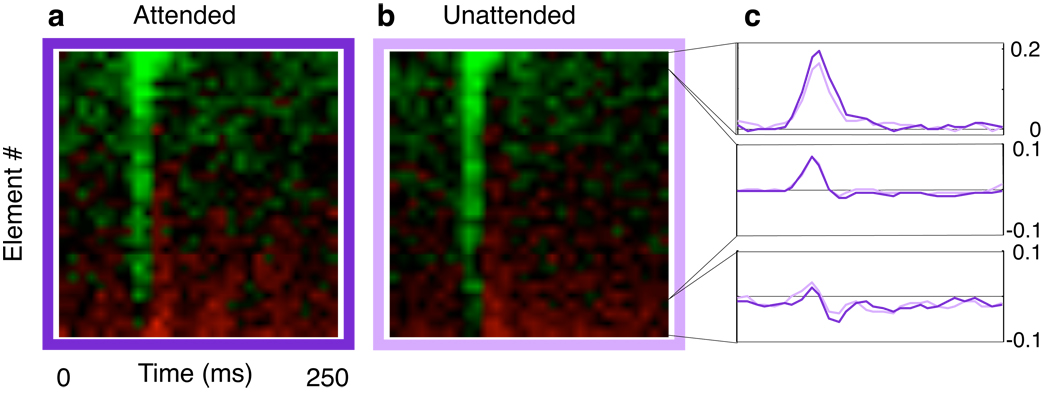

For every neuron, we computed separate linear receptive fields for the two epoch groups (attended and unattended). The spatial coefficients of these kernels were then sorted according to preferred direction sensitivity and resulting sorted kernels from each neuron were summed to produce average kernels (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Average linear receptive field estimates derived by random sequence subsamples selected according to behavioral performance. Kernels from individual neurons were sorted according to Gabor element location. The element with the greatest preferred motion (green) response is on the top, and the element with the greatest anti-preferred motion (red) response is on the bottom. Average kernels were computed using these spatially sorted kernels. Temporal response profiles (c) were constructed by summing those elements with strong preferred motion responses (top), strong anti-preferred responses (bottom), and all other positions (middle). Kernel changes are not consistent with a pure gain change. Attention increases responses (dark vs light), but only at the locations most sensitive to preferred (top, right) motion. Little change in sensitivity in seen outside of the receptive field peak (middle and bottom, right).

We then computed several receptive field metrics for both the attended and unattended kernels. For each kernel, coefficient noise was estimated by computing the standard deviation of coefficients with delays smaller than the neuronal latency. Because, in individual neurons, measurements of the sensitivity of off-peak locations are particularly susceptible to noise and variability, we computed metrics based only on those kernel coefficients with S/N ratios greater than three. To derive non-parametric measures of receptive field size and duration, we collapsed the spatiotemporal kernel along the temporal and spatial dimensions respectively and sorted each 1-D profile according to amplitude. Spatial size was derived from the sorted spatial profile as the (number of spatial elements that were at least half-maximal, while duration was derived from the sorted temporal profile as the number of frames that were at least half maximal. Finally, we defined kernel power as the RMS of all coefficients that exceeded the S/N criterion of three.

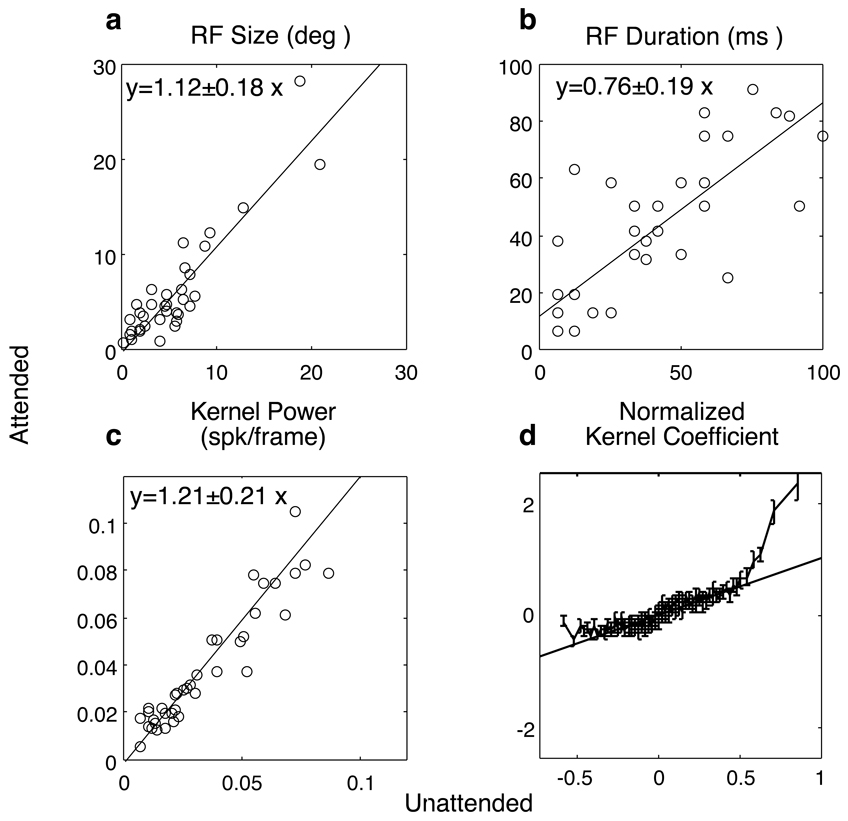

Again, as expected, kernel power increased with attention (Fig 4c). Although this would be found in a pure gain modulation of the receptive fields, there were several changes that were not consistent with such a notion. First, the modulation of kernel power, as measured by regression (Fig 4c, slope=1.21 ± 0.21), was larger than the modulations seen in baseline activity (not shown, slope=0.98 ± 0.10). Additionally, while attention has modest effects on the spatial extent of the receptive fields (Fig 4a, regression slope=1.12 ± 0.18), it tended to slightly decrease the temporal duration (Fig 4b, regression slope=0.76 ± 0.19). To directly examine whether kernels were scaled uniformly, for every neuron, we peak normalized each coefficient of the unattended kernel and plotted how that coefficient changed with attention. We then grouped all of the data from all of the neurons in 100 bins according to normalized unattended magnitude. Such analysis reveals that most kernel coefficients were not significantly modulated by attention (Fig 4d), but that strong positive modulation was seen near the peak of the kernel. Interestingly, significant suppression was observed for the most negative coefficients (corresponding to preferences for motion in the anti-preferred direction). Thus the increase in kernel power was due to selective changes in spatiotemporal receptive fields, rather than a uniform gain change.

Figure 4.

Kernel parameters as a function of attention. Kernel noise was estimated by computing the standard deviation of kernel elements at delays shorter than response latency (<50 ms). Receptive field size and duration were defined according to the number of spatial and temporal position in the array whose magnitude was greater than half peak amplitude. Kernel power is defined by the RMS of kernel elements above this criterion. Attention effects were assessed by applying regression analysis to parameters as a function of attention. The primary effect of attention was to decrease RF duration (b) and increase kernel power (c). This increase in power reflects an improvement in the signal to noise ratio of neurons in signaling the preferred direction of motion. The effects of attention cannot be described by a simple gain change because attention affects kernel power preferentially effects the most positive and negative kernel coefficients (d). Kernel coefficients were normalized according the peak of the unattended kernel for each cell. The diagonal line indicates a line of slope one which defines no attention effect; error bars indicate 1 SEM.

One simple explanation for this effect would be that non-uniform changes in the kernel are arising simply because the analysis employed to derive these kernels failed to incorporate non-linearities. This is particularly worthy of consideration given the prevalence of non-linearities: in almost all neurons (40 out of 41) such non-linearities were significant when trying to quantify the relationship between motion-strength and neuronal discharge. For example, an increase in the exponent term of the non-linearity associated with attention would result in the largest kernel coefficients seeing the greatest increase (Fig 4d). Models of attention based on changes in normalization that individual neurons receive from a surrounding pool of neurons (Lee and Maunsell, 2009) are consistent with a change in the relationship between linear kernels and discharge. In this scheme, the apparent changes in linear kernel properties are actually due to changes in non-linearity for which the purely linear model cannot account. Using predictions for average activity as a function of stimulus strength, we compared such a model, in which non-linearities are dynamic but the linear kernel is static, with an alternative model in which the linear kernels are dynamic but a fixed non-linearity is applied. To test such models we constructed linear kernel estimates and non-linear transformations using a random sampling of 90% of trials for each neuron. In the first model, the static kernel is first computed using all data within these trials. Then separate non-linearities were computed using this kernel with the observations from attended and unattended epochs. In the second model, a static non-linearity is computed using that static kernel and then applying it to linear kernels separately derived from the attended and unattended epochs. In both cases, goodness-of-fit was computed by predicting average firing rate as a function of stimulus strength for attended and unattended epochs separately in the remaining 10% of trials. The analysis reveals that the dynamic non-linearity model is significantly better than the dynamic kernel model at explaining neuronal discharge for both attended and unattended epochs in individual neurons (Fig 5, paired t-test, p<0.001). For all three animals, we found neurons in which the dynamic non-linearity model was able to explain the unmodeled 10% of trials, while the dynamic kernel was not.

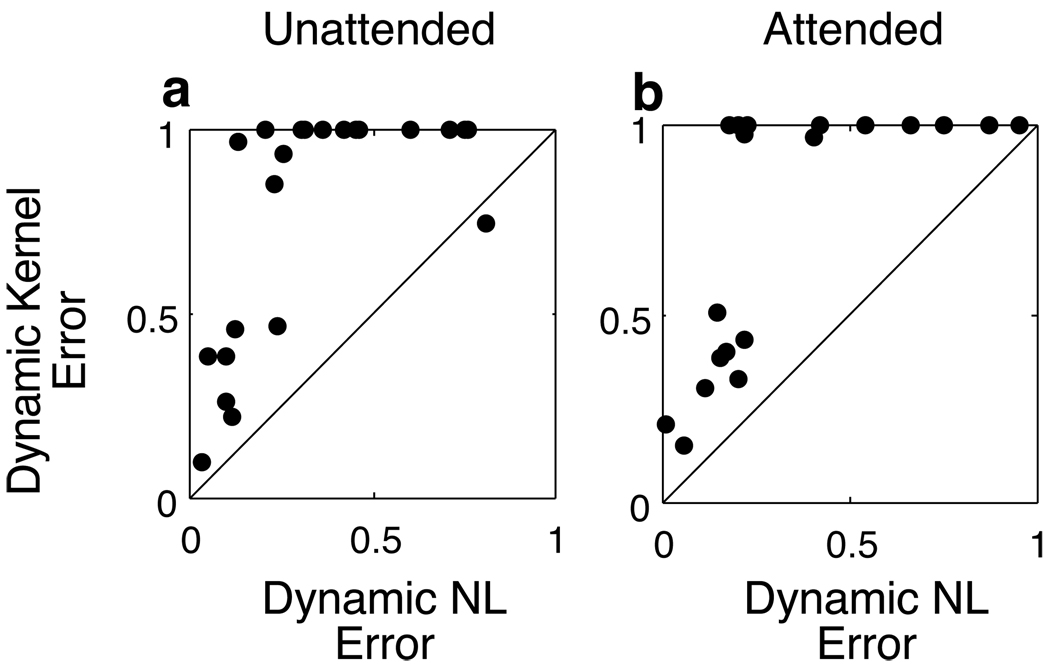

Figure 5.

Goodness of fit of attention models evaluated by predicting discharge using specific linear kernels and non-linearites using the method of Figure 2f. Dynamic kernels are based on subsampling such as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4; static kernels are based on the complete sampling of stimulus and discharge observed with a neuron. Errors in fit were normalized according the explainable variance to yield an error percentage and computed separately for attended (b, N=24) and unattended (a, N=20) epochs. Dynamic non-linearities with static linear kernels provided a better explanation of the firing rates (paired t-test, p<0.001) than a model in which the linear kernel changed with attention but the non-linearity was static (a and b). In all three animals we found neurons in which dynamic non-linearities were able to explain firing during both attended and unattended epochs, but the dynamic kernel model completely failed (points in the upper left corner).

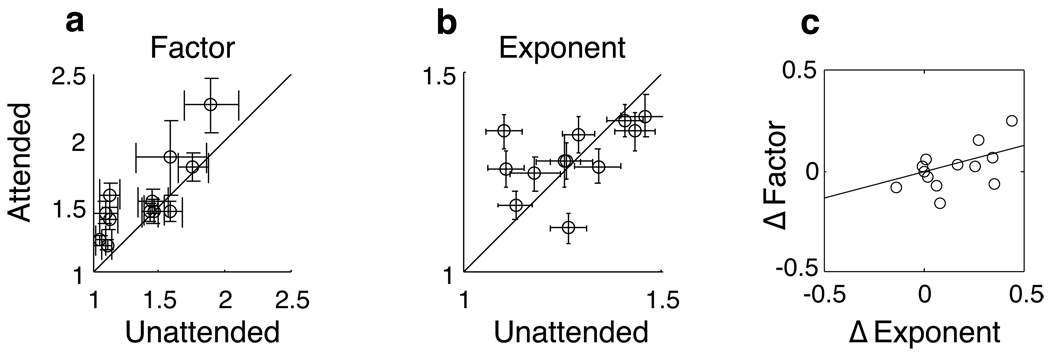

To examine the nature of this apparent change in non-linearity, we plotted the gain and exponent coefficients as a function of attention for the 13 neurons in which both the dynamic kernel model and the dynamic non-linearity model were able to explain at least half of the variance. We found that while the gain terms were significantly increased with attention (paired t-test, p<0.02) (Fig 6a), no such consistency was seen with the exponent terms within our sample (Fig 6b). The lack of consistent increases in the exponent term would seem to be inconsistent with the preferential increase of large kernel coefficients in a purely linear model of attention (Fig 4d). However, an analysis of the correlation between changes in the gain and exponent terms reveals a potential explanation. Because there is a significantly positive correlation (r=0.50, p<0.001) between the attention-associated changes in gain and exponent (Fig 6c), neurons with strong attentional modulation tend to have positive changes in both terms, while the neurons with weak changes or actual decreases in exponent have modest changes in attentional gain as well.

Figure 6.

Non-linearity parameters for those 13 neurons in which changes in non-linearity improved fit. Errors bars indicate standard deviations of the parameters acquired by bootstrap methods. Attention significantly increased the gain of such neurons (a, paired t-test, p<0.02), but did not consistently increase the exponent terms (b). However, attentional changes in the exponent were significantly correlated with changes in the gain term (c, r=0.50, p<0.001), suggesting that cells that were strongly modulated by attention tended to exhibit increases in both the gain and exponent terms.

4 Discussion

We used a reverse correlation analysis to study the spatiotemporal receptive fields of MT neurons while animals were engaged in a rapid motion detection task. Animals were required to detect motion stimuli that, due to their brevity, were invisible prior to training. Expectations played a critical role in their performance; the animals’ performance was strongly correlated with the probability of pulse appearance, and the animals’ decisions were based on nearly optimal spatiotemporal integration when pulses were likely (Ghose, 2006). We find that these expectations also have a significant effect on the receptive fields of individual neurons: selectivity to motion was enhanced beyond what would be expected from a multiplicative gain change and was consistent with a change in the non-linearities with which neurons summed motion information. This suggests that changes in the non-linearities of individual neurons may play a large role in the optimization of sensory integration seen with training.

This study is the first to demonstrate that receptive fields can be altered over relatively small time scales of 100 of milliseconds. In the vast majority of studies, it assumed that behavior state is constant over the course of an experimental trial. For example, attentional effects are commonly measured for trials in which a cue presented at the beginning of a trial or trial block indicates behavioral relevance. By contrast, our modulations were observed without any explicit cueing of likelihood. Because these strategies accurately reflected a schedule with relatively rapid changes in likelihood, we able to study the dynamics of attention effects with much greater fidelity. Our data (Fig 1b), demonstrate behavior state can rapidly and precisely change within hundreds of milliseconds and these fluctuations can have large effects on the receptive fields of individual neurons. The ease with which the modulations occur, namely with any explicity cueing, as well as their magnitude, suggests that intrinsically formed strategies may be especially problematic when interpreting data from paradigms in which behavioral state is assumed to be relatively stationary across time and across experimental sessions.

This study is also the first to apply directionally balanced noise techniques to explore the spatial structure of MT receptive fields. Although, the spatial heterogeneity of MT receptive fields has been well established by classical electrophysiological techniques (Raiguel et al., 1995)(Xiao et al., 1995)(Xiao et al., 1997), previous receptive field mapping studies have either assumed spatial homogeneity (Cook and Maunsell, 2004) or tested spatial differences in a limited manner. For example, spatial mapping studies have either relied solely on patches of preferred direction motion (Britten and Heuer, 1999; Anton-Erxleben et al., 2009) or averaged over all spatial locations (Livingstone et al., 2001). Because of the relative weakness of our stimulus, it is poorly suited for studying purely modulatory effects such as are associated with surround suppression. However, our data demonstrate that MT neurons have a rich spatial structure within their classical receptive field, in which different regions respond to preferred and anti-preferred motion (Fig 2 and Fig 3).

As can be seen in the population kernels (Fig 3), the sensitivity to anti-preferred motion follows sensitivity to preferred motion (Borghuis et al., 2003). This is distinct from the classic spatial surround (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2009), which refers to the suppressive modulatory influence of preferred motion outside of the classical receptive field. The anti-preferred motion sensitivity reported here is not modulatory nor is it distant from regions with preferred direction sensitivity. In this respect, it is analogous to an OFF-region of a simple cells in primary visual cortex. Similar to the effect of ON-OFF luminance selectivity to simple cells’ spatial frequency bandwidth, the selectivity to anti-preferred motions notably sharpens temporal frequency tuning (Bair and Movshon, 2004) and is particularly well suited for the detection of rapid motion transients (Buracas et al., 1998). While sensitivity to anti-preferred motion has been observed in studies employing high-contrast bars (Livingstone et al., 2001)(Pack et al., 2006 Jan 18), it has not been observed in the linear kernels obtained from random dot stimuli (Cook and Maunsell, 2004). One possible reason for this difference is that the relative weakness of local motion energy present in such random dot stimuli preclude the detection of more subtle features such as trailing inhibition. The use of narrow-band, high contrast local motion signals in our study might also explain the sharpness of our temporal sensitivity profiles in comparison with previous studies. Kernels derived from random dot stimuli had unimodal temporal envelopes of around 40 ms (Cook and Maunsell, 2004), which, as can been seen in our population data (Fig 4b), is considerably larger than the duration of preferred motion sensitivity in much of our neuronal sample.

This study is the first to quantify non-linearities subsequent to linear motion processing in MT neurons. Although the magnitude of these non-linearities (in terms of the difference between the exponent terms and one) are modest (Fig 6), they are significant: for almost all neurons, non-linearities were necessary to account for the relationship between stimulus and discharge on a frame-by-frame basis. Morever, because these non-linearities can significantly change with behavioral state 6, the failure to incorporate such non-linearities complicates the interpretation of the effects of attention on receptive fields.

As demonstrated here, some changes in linear kernel properties can be explained solely by changes in non-linearity. The strength of the increase in apparent kernel strength (Fig 4) reflects changes in both gain and exponent terms (Fig 6) rather than changes in the linear kernel (Fig 5). Consistent with this notion, when linear kernels are fit separately for attended and unattended epochs, we find that changes in the spatial and temporal extents are modest and not consistent (Fig 4). However, there are several studies suggesting that attention can produce significant changes in linear receptive fields (Ben Hamed et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2007; Womelsdorf et al., 2008 Sep 3), Given that these studies did not explicitly examine non-linearities, it is possible that in some cases attention was actually changing non-linearities in addition to, or instead of, changing in linear summation. For example, imagine a situation in which the sole effect of attention was an increase in the exponent term of the non-linearity (such as might be associated with normalization changes (Lee and Maunsell, 2009)) without any change in linear receptive field structure. If one conducted a purely linear analysis, peak values of the kernel would appear to be preferentially amplified with attention and one would conclude that the RF had “shrunk.” This might explain the diversity of results regarding the effects of attention on receptive field size even with the same studies. For example, in area V1, the effect of attention on receptive field size depends on eccentricity (Roberts et al., 2007), while in area MT, the effect depends on the exact location relative to the receptive field to which attention is directed (Anton-Erxleben et al., 2009). Similarly, subtle changes in the locus of attention may be responsible for the diversity of non-linearity changes observed (Fig 6) with attention, but our data set is not yet sufficient to examine this issue.

Changes in non-linearity can not readily explain all attentional phenomena. For example, several studies have reported shifts in receptive field weighting toward to the locus of attention (Connor et al., 1997; Ben Hamed et al., 2002; Womelsdorf et al., 2006). Models suggest that the effects of attention of receptive field extent and structure depend on both the locus and spatial extent to which attention is directed (Ghose, 2009). In our experiment, the extent of spatial attention is relatively large: unlike designs in which a nearby distractor must be ignored (Ghose and Maunsell, 2008), in our task it is advantageous to broadly integrate motion information over the entire array (Ghose, 2006). For such broad allocations of attention, it is unlikely that spatially specific inputs would be amplified to create changes in linear receptive field structure. This is consistent with our observations that, for a given cell, the same linear kernel is able to explain responses during both attended and unattended periods of time.

Our results confirm the powerful role that expectations can play in the processing of visual information, because both changes in performance and receptive field properties occurred without any explicit cuing. Although our task employed the detection of a motion pulse which occurred at a random point of time within trials, many aspects were predictable. The schedule determining where and when pulses were likely to occur was kept constant throughout training and recording, as was the duration and coherence of the motion pulse to be detected. Additionally, the actual direction of coherent motion was consistent throughout individual recording sessions. Previous behavioral analyses revealed that the animals made use of these consistencies and employed nearly optimal integration; they integrated motion information in close accordance with the direction, size, and duration of the motion pulse to be detected (Ghose, 2006). Such optimization could arise from changes in the sensory encoding of motion information or in the decoding of sensory signals to arrive at a perceptual judgment. While our present results do not preclude the possibility that the decoding of MT signals is altered as a consequence of training (Chowdhury and DeAngelis, 2008), experiments in which encoding and decoding reliability changes in our paradigm are directly compared suggest suggest that changes in sensory coding are likely to dominate (Harrison and Ghose, unpublished observations). Our receptive field analyses point to how anticipation might improve the encoding of motion information by MT neurons. There are parallels between the optimization seen in the behavioral kernel, and the changes seen in MT receptive fields. For example, sensitivity to a single direction of motion was more spatially uniform during periods of good performance. Similarly, there was a slight, although not significant, tendency for the spatial size of MT receptive fields to increase during such periods. With regard to the temporal integration, the behavioral kernels were temporally sharper when the pulse was anticipated, and increases in MT sensitivity were confined to the peaks of the temporal sensitivity profile (Fig 3).

These results provide an important complement to previous probabilistic theories of perception which have emphasized the importance of prior knowledge, especially in noisy environments or with ambiguous percepts (Kersten et al., 2004). For example, in many Bayesian models, the decoding of sensory signals explicitly incorporates statistics about the visual environment. Our results suggest another mechanism by which statistics can influence perception: the optimization of the sensory signals themselves. The observed changes in MT neurons were consistent with such optimization. Their increased responsiveness to motion arose from an increase in sensitivity to preferred motion without comparable changes in baseline activity (Fig 4). These changes are in exact accordance with an increased capability to reliably signal the behavioral relevant motion pulse. Indeed, when the sensory reliability of MT neurons in our sample (Ghose and Harrison, 2009) is separately computed for epochs of good and poor performance (Harrison and Ghose, unpublished observations), we find such an effect. That information rate analysis found that changes in reliability occurred in the absence of changes in either spike precision or sensory latency. This is also in accordance with our receptive field measurements, in which the temporal envelopes and latencies were unaffected by attention (Fig 3).

Although the attention modulation of overall motion sensitivity, as measured by changes in kernel power, is similar in magnitude to the modulations of responses reported in previous studies of MT activity (Seidemann and Newsome, 1999)(Cook and Maunsell, 2002), the specific changes are notably different. In particular, a previous study employing reverse correlation techniques to infer the spatiotemporal integration of motion information by MT neurons, observed changes entirely consistent with gain modulation (Cook and Maunsell, 2004). In this study, attention increased responsiveness but did not alter the spatiotemporal envelope or direction selectivity of MT neurons. However, there are several notable differences between task design of that study and that of the experiments described here. In the previous study, the motion to be detected was sustained and only weakly coherent. By contrast, our behaviorally relevant stimulus was strongly coherent but transient. This difference has clear behavioral effects: reaction times in the previous study were considerably larger than those (Ghose and Harrison, 2009) (< 250 ms) of our paradigm. This suggests that the motion processing invoked by these tasks may differ in a number of ways. First, because of large reaction times for the detection of weak but sustained motion, attention could “waver” over the course of the trial without a substantial impact on performance. For example, if reaction times are on the order a second, fluctuations in behavioral state occurring over hundreds of milliseconds may be relatively inconsequential. These changes could be in the form of either changes in overall vigilance or shifts in the focus of attention. By contrast, in our design, given the poor performance observed during epochs in which the pulse was unlikely, a brief shift in attention during the actual presentation of the pulse would likely preclude its detection. Second, there was no impetus for the animal to sharpen temporal integration on the basis of this stimulus. Unlike transient stimuli, the detectability of noisy but sustained motion will improve with more extensive temporal integration. Third, in the previous experiment there was no evidence that substantial perceptual learning was taking place. By contrast, the duration of our motion pulses were gradually lowered over a period of months, and even after they were held constant, changes in perceptual integration were observed with repeated training (Ghose, 2006).

The difference between our results and those of previous studies suggesting pure gain modulation (Cook and Maunsell, 2004)(Treue and Martinez Trujillo, 1999) suggests that attentional mechanisms are flexible and can change visual representations in a task specific manner. Indeed, different strategies of deploying attention can result in different modulations of activity both at the level of single neurons (Ghose and Harrison, 2009)(Boudreau et al., 2006) and across populations of neurons (Hopf et al., 2006). In this notion, changes in gain, which may be relatively easy to implement physiologically (Salinas and Thier, 2000)(Sripati and Johnson, 2006). would be applied in a variety of situations (McAdams and Maunsell, 1999b), whereas more specific modulations (Martinez-Trujillo and Treue, 2004) might be invoked when the task demands it. One uncertainty is the amount of task familiarity and training required to accomplish such attentional reallocations. For example, because our results are from highly trained animals, it is uncertain whether the effects of attention would be comparable at earlier stages of training. In particular, is awareness of the need to detect transients sufficient to invoke such selective attention modulation, or is more extensive training required? To study this issue, our lab is currently pursuing studies of MT physiology during the process of training. If mere familiarity with the task is sufficient to have the dramatic effects on neuronal reliability and sensory processing demonstrated here, then expectations, which are formed in any familiar situation, may play a fundamental role in the processing of visual information in everyday situations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anton-Erxleben K, Stephan VM, Treue S. Attention reshapes center-surround receptive field structure in macaque cortical area mt. Cereb Cortex. 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W, Movshon J. Adaptive temporal integration of motion in direction-selective neurons in macaque visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24(33):7305–7323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0554-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W, O’Keefe LP. The influence of fixational eye movements on the response of neurons in area MT of the macaque. Vis Neurosci. 1998;15(4):779–786. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898154160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hamed S, Duhamel JR, Bremmer F, Graf W. Visual receptive field modulation in the lateral intraparietal area during attentive fixation and free gaze. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(3):234–245. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghuis B, Perge J, Vajda I, van Wezel R, van de Grind W, Lankheet M. The motion reverse correlation (mrc) method: a linear systems approach in the motion domain. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau CE, Williford TH, Maunsell JHR. Effects of task difficulty and target likelihood in area v4 of macaque monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(5):2377–2387. doi: 10.1152/jn.01072.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten K, Heuer H. Spatial summation in the receptive fields of MT neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19(12):5074–5084. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05074.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten K, Newsome W, Shadlen M, Celebrini S, Movshon J. A relationship between behavioral choice and the visual responses of neurons in macaque MT. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13(1):87–100. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000715x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten K, Shadlen M, Newsome W, Movshon J. The analysis of visual motion: a comparison of neuronal and psychophysical performance. J Neurosci. 1992;12(12):4745–4765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04745.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buracas G, Zador A, DeWeese M, Albright T. Efficient discrimination of temporal patterns by motion-sensitive neurons in primate visual cortex. Neuron. 1998;20(5):959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Beutter B, Eckstein M. The time course of visual information accrual guiding eye movement decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(35):13086–13090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305329101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichilnisky EJ. A simple white noise analysis of neuronal light responses. Network. 2001;12(2):199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SA, DeAngelis GC. Fine discrimination training alters the causal contribution of macaque area mt to depth perception. Neuron. 2008;60(2):367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor C, Preddie D, Gallant J, Van Essen D. Spatial attention effects in macaque area v4. J Neurosci. 1997;17(9):3201–3214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03201.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook E, Maunsell J. Attentional modulation of behavioral performance and neuronal responses in middle temporal and ventral intraparietal areas of macaque monkey. J Neurosci. 2002;22(5):1994–2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01994.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EP, Maunsell JHR. Attentional modulation of motion integration of individual neurons in the middle temporal visual area. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7964–7977. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5102-03.2004. (1529–2401 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa A, Lupianez J, Tudela P. The attentional mechanism of temporal orienting: determinants and attributes. Exp Brain Res. 2006 Feb;169(1):58–68. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis G, Ohzawa I, Freeman R. Spatiotemporal organization of simple-cell receptive fields in the cat’s striate cortex. II. Linearity of temporal and spatial summation. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69(4):1118–1135. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo J, Johnson K, Hsiao S. Structure of receptive fields in area 3b of primary somatosensory cortex in the alert monkey. J Neurosci. 1998;18(7):2626–2645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02626.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty JR, Rao A, Mesulam MM, Nobre AC. Synergistic effect of combined temporal and spatial expectations on visual attention. J Neurosci. 2005 Sep 7;25(36):8259–8266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1821-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing C. Expectancy and visual-spatial attention: effects on perceptual quality. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1988;14(2):188–202. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.14.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein M, Shimozaki S, Abbey C. The footprints of visual attention in the posner cueing paradigm revealed by classification images. J Vis. 2002;2(1):25–45. doi: 10.1167/2.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose GM. Strategies optimize the detection of motion transients. J Vis. 2006;6(4):429–440. doi: 10.1167/6.4.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose GM. Attentional modulation of visual responses by flexible input gain. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(4):2089–2106. doi: 10.1152/jn.90654.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose GM, Harrison IT. Temporal precision of neuronal information in a rapid perceptual judgment. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(3):1480–1493. doi: 10.1152/jn.90980.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose GM, Maunsell JHR. Spatial summation can explain the attentional modulation of neuronal responses to multiple stimuli in area V4. J Neurosci. 2008;28(19):5115–5126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0138-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur M, Snodderly DM. Visual receptive fields of neurons in primary visual cortex (v1) move in space with the eye movements of fixation. Vision Res. 1997;37(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf JM, Luck SJ, Boelmans K, Schoenfeld MA, Boehler CN, Rieger J, Heinze HJ. The neural site of attention matches the spatial scale of perception. J Neurosci. 2006;26(13):3532–3540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4510-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten D, Mamassian P, Yuille A. Object perception as bayesian inference. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:271–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylo D, Reeves A, Scharf B. Expectancy of line segment orientation. Spat Vis. 1996;10(2):149–162. doi: 10.1163/156856896x00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Maunsell JHR. A normalization model of attentional modulation of single unit responses. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone M, Pack C, Born R. Two-dimensional substructure of mt receptive fields. Neuron. 2001;30(3):781–793. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Trujillo JC, Treue S. Feature-based attention increases the selectivity of population responses in primate visual cortex. Curr Biol. 2004;14(9):744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams C, Maunsell J. Effects of attention on orientation-tuning functions of single neurons in macaque cortical area V4. J Neurosci. 1999a;19(1):431–441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00431.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams C, Maunsell J. Effects of attention on the reliability of individual neurons in monkey visual cortex. Neuron. 1999b;23(4):765–773. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykamp DQ, Ringach DL. Full identification of a linear-nonlinear system via cross-correlation analysis. J Vis. 2002;2(1):1–11. doi: 10.1167/2.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pack CC, Conway BR, Born RT, Livingstone MS. Spatiotemporal structure of nonlinear subunits in macaque visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2006 Jan 18;26(3):893–907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3226-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M, Snyder C, Davidson B. Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol. 1980;109(2):160–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiguel S, Van Hulle M, Xiao D, Marcar V, Orban G. Shape and spatial distribution of receptive fields and antagonistic motion surrounds in the middle temporal area (V5) of the macaque. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7(10):2064–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Delicato LS, Herrero J, Gieselmann MA, Thiele A. Attention alters spatial integration in macaque v1 in an eccentricity-dependent manner. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(11):1483–1491. doi: 10.1038/nn1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulston M. Estimating the errors on measured entropy and mutual informatiojn. Physica D. 1999;125:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rust N, Schwartz O, Movshon J, Simoncelli E. Spatiotemporal elements of macaque v1 receptive fields. Neuron. 2005;46(6):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust NC, Mante V, Simoncelli EP, Movshon JA. How mt cells analyze the motion of visual patterns. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(11):1421–1431. doi: 10.1038/nn1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salidis J. Nonconscious temporal cognition: learning rhythms implicitly. Mem Cognit. 2001;29(8):1111–1119. doi: 10.3758/bf03206380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Abbott L. Invariant visual responses from attentional gain fields. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77(6):3267–3272. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Thier P. Gain modulation: a major computational principle of the central nervous system. Neuron. 2000;27(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidemann E, Newsome W. Effect of spatial attention on the responses of area mt neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(4):1783–1794. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen M, Britten K, Newsome W, Movshon J. A computational analysis of the relationship between neuronal and behavioral responses to visual motion. J Neurosci. 1996;16(4):1486–1510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01486.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpee TO, Miller KD, Stryker MP. On the importance of static nonlinearity in estimating spatiotemporal neural filters with natural stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99(5):2496–2509. doi: 10.1152/jn.01397.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson W, Manahilov V. Matched filtering in motion detection and discrimination. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;268(1468):703–709. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripati AP, Johnson KO. Dynamic gain changes during attentional modulation. Neural Comput. 2006;18(8):1847–1867. doi: 10.1162/neco.2006.18.8.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treue S, Martinez Trujillo J. Feature-based attention influences motion processing gain in macaque visual cortex. Nature. 1999;399(6736):575–579. doi: 10.1038/21176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Pieper F, Treue S. Dynamic shifts of visual receptive fields in cortical area mt by spatial attention. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(9):1156–1160. doi: 10.1038/nn1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Treue S. Receptive field shift and shrinkage in macaque middle temporal area through attentional gain modulation. J Neurosci. 2008 Sep 3;28(36):8934–8944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4030-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Raiguel S, Marcar V, Koenderink J, Orban G. Spatial heterogeneity of inhibitory surrounds in the middle temporal visual area. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(24):11303–11306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Raiguel S, Marcar V, Orban G. The spatial distribution of the antagonistic surround of MT/V5 neurons. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7(7):662–677. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.7.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]